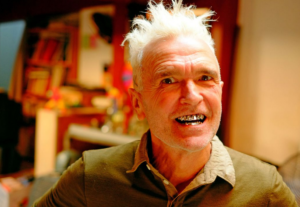

Blood, Noise and the Spectre of Neoism: an interview with Istvan Kantor (2013)

Mike: There was a moment – was it longer than that? – when I looked forward to meeting the many Neoists I imagined crowding the streets of Montreal. Though I was uncertain what this new art group subscribed to, and then it turned out it wasn’t so much a group but an attitude with a single name.

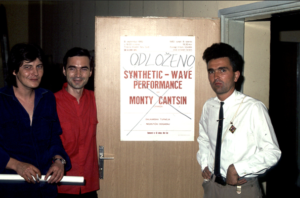

Istvan: While each Neoist has a different concept about the origin and beginning of Neoism and we refuse to celebrate historical events such as the current 30st Anniversary of Neoism, still, for the sake of arguments, smiles and a few drinks, let me remind you that all hell broke out on May 22nd 1979 in Montreal at the corner of McGill and Sherbrook streets. It was a sunny day. Accompanied by Lion Lazer, I, Monty Cantsin, today known as Istvan Kantor Monty Cantsin? AMEN!, was sitting on a Neoist Chair, a chair with a Neoism sign attached to the back of the chair, and distributed flyers to passers-by. People were curious to know what Neoism was about. We didn’t have any idea but from the conversations we learned a lot. Thirty years later I still have difficulties to explain what is Neoism, however, at the same time, I can say that it is still the most revolutionary street subvertainment. You agree or not it doesn’t matter. What matters is that anyone can sit on the Neoist Chair and argue about Neoism or get up and break the Neoist Chair. I propose that you try one of these tomorrow, on May 22nd 2009, and see what happens. Otherwise you can do whatever you like in the name of Neoism! Our conspiracy is the potential energy of the future, present and past. We are for perpetual change and total freedom!

Mike: Neoism takes aim at a society drowning in pictures, which has replaced being with having (we are all consumers). You write, “You caught a disease – a radically infectious, contagenius disease. And it propels you to enrapture yourself with every little fragment of the conspiracy – be it a slogan, a poster on the wall, an apartment festival, writing in magazines about this subject that initially wrapped you up and caught you in its spell. Then, as you slowly realize you’ve been duped a bit, you get angry, because you realize you’ve demystified this whole fucking experience. And all you’re left with are these two devastating goddam names: MONTY CANTSIN and NEOISM. Nothing else.”

Here you offer Neoism itself as part of the problem, just one more ism to be taken up, used and discarded. Another veil to be seen through. But this question of the name tugs at me. You are not the only Monty Cantsin, are you? Part of this persona project is to multiply, virus-like, the act of naming itself, until it begins to unravel.

Istvan: I am not the only Monty Cantsin in the laboratory of life. Beside me, there are at least as many Monty Cantsins as the population of the decaying world. Push the past out of the way! Eat dirt and try to convince other people to join you in this bucolic pursuit! Monty Cantsin is a blood-ridden hitchhiker who thumbs a ride on every cause from Christianity to Neoism via Communism. Monty Cantsin is a fanatic lover of himself, without needing a Stalin (or a Christ) to worship or die for. There are conscious and unconscious Monty Cantsins, people who know and don’t know they are Monty Cantsin.

Anyone can be Monty Cantsin without restrictions of religion, gender, race, age, anything. That which anybody can do is only worth doing. There are no two identical Monty Cantsins. Every Monty Cantsin is a different individual with the same name. The way to fulfillment is through recognition and realization of the fact that we are each and all unique. NEOISM is the materialization of a new savior, Monty Cantsin, the reactivation of living infinity lost in contemplation. Monty Cantsin is duty bound to freely express his/her convulsive obscurity in the darkness of unresolved problems. Freedom is totalitarian. Stop analyzing and start fucking.

Mike: Could you describe one of your early Neoist performances?

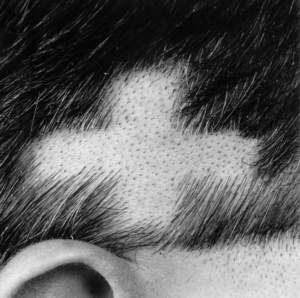

Istvan: The audience was making a huge noise when somebody switched off the light. Tim Harvey threw some petards into the middle of the room. I announced that I was a Renaissance, Baroque, Classical, Romantic and Modern musical dictionary and that my name was Monty Cantsin. I took a long sheet of aluminum paper and said that it was a Monty Cantsin movie. I dropped my pants and covered my dick with the aluminum paper, then I sat behind the slide projector and directed the image on my body. Then I took off the aluminum paper from my dick and covered my face with it and then crumpled it into a pellet. There is the reflecting self and the self the reflecting self reflects. At a certain point I fell across a chair, arms outstretched, to become the cross I was nailed to. My face turned black and blue, and I was uncertain whether my heart was still beating. I had a full vision of my entire life. David, Paul, and Eric played improvised music, then I passed around the HAT OF THE PROPHET and everybody tried it on. Then we sang The Correspondence Blues, and I recited the “Who is Monty Cantsin?” text. I declared that everybody is Monty Cantsin in this room. I plugged in an electric shaver and started buzzing, the audience buzzed too. I howled, “WWWEEEE ARRRRRE ALL HEEEEEERRRRRE, WWWWWEEEE AAAAAARRRRRRRE ALLLLLLL HEEEEEEERRRRRRRRE! THIS IS NO FICTION.” A few fainted. Still others fell into depression, or soared into euphoria, or felt omnipotent, or persecuted.

Mike: Your video and performance work often protests technology using technological means. There is a fear of being plugged in coupled with a nearly technocratic precision.

Istvan: I’m frightened and I’m ashamed of myself for being frightened. I’m ashamed of myself for becoming what I have never wanted to become. And that’s why I am frightened.

I’ve been a victim of technology for a long time but somehow I always had the strength to resist. But now it seems like I’ve lost my life-long battle and my revolution has failed. Please let me tell you what happened. It might be a good learning experience for you and it might help me to heal my troubled mind through confession therapy.

I have lived for over fifty years now and I have seen life as it is. I have seen misery, pain, desolation, despair, destruction, fire, blood and everything else. For a couple of years I also worked as paramedic nurse in Budapest before going to medical university. And of course I have seen lots of people dying. Mostly ordinary people who died of heart attacks, accidents, suicide… They didn’t have the glorious death of heroes, they didn’t have famous last words.

Many of them died in my arms. As I looked into their eyes I saw not only fear but also confusion. They were frightened and there was a question in their eyes: why? Were they wondering about why they had to die? No. They knew one day they would have to die. So then what they were wondering about? Maybe they were wondering about who I was, this strange guy holding them at the very last moment of their life. It could be. But I think what they were really wondering about was something else. I think they were wondering about why they had ever lived!

Mike: While you are always at the centre of your personal media maelstrom, it seems you are also always reaching out, networked, passing the torch, and that these openings are wounds which bring you to new discoveries.

Istvan: I always learned from other people. Annabel Chong is one of them. I’m sure you have also heard about this amazing porn artist who once had sex with 251 men within eight hours. That was a world record. She once said in an interview that “Sex is good enough to die for.” But can I say that, “Art is good enough to die for?” Well, if art is sex and sex is art, then art is good enough to die for. Or if art is revolution, and revolution is art, then art is good enough to die for as well. I want to live and die for art! If it doesn’t make you horny, it’s not art!

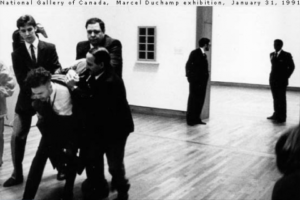

Mike: You are very critical of art institutions and their authoritarian, bureaucratic positions. You like to call yourself a criminal and have been often jailed for your art interventions in museums. You want to separate yourself from the art world, and get away from “the prison of art.” In the meantime, you wear a red armband that signifies your revolutionary ideas. Sometimes these ambiguities, even small clouds of confusion, gather round your work, and perhaps that is your hope after all, but then, with a sudden gesture, you make everything so clear.

Istvan: I was always very curious about prison life. Once, when I was in a high security prison, the guards and my prison mates thought I was some kind of mental product because even though they beat me up and sexually abused me I kept being friendly to everyone. I let them gang bang me in the shower or punch my face until I was bathing in my own blood. For some reason my behavior irritated them and soon I was transferred to a psychiatric institute. There I had to wear a red armband because I was considered a dangerous criminal and the red armband was a sign of dangerous criminals. I have worn it ever since.

Mike: Could you tell me something about your earliest memories?

Istvan: Once, very long time ago, maybe millions of years ago, I was a monolith. You know what that is? It is a large cube, a single massive stone. It’s also called “prima material.” I was a very dark monolith, a black monolith radiating free signals. In other words, I was a single standing transmission unit. I simultaneously transmitted free information from different parts of the universe. Like a subatomic particle that can be in at least two places at the same time, I was standing erect at several places at the same moment. I was standing here on the Earth, and also on the Moon and Jupiter, and maybe elsewhere. I don’t remember everything. But I know that I transmitted free creative information and played a principal role in initiating civilization.

Then I turned into a filing cabinet. Filing cabinets are monolithic sculptural objects made to store information. How boring to be a file cabinet, one might say. No, not at all. It was very exciting. I was filled with information most of the time, but sometimes I was empty. People pushed thick files of information in my body, they were moving drawers in and out of my body, they stuffed me with their ideas. I was excited all the time, it was like a constant intercourse, a spontaneous orgasmic performance. And soon I became connected to other file cabinets all around the world through electronic networks. People digitized all the information that was stored in me. They turned it into invisible numbers. All the information stored in my body was sent to other file cabinets via the computer system. On the other end, the digital information was turned into hard copies again which required more and more file cabinets. In spite of the dominating force of digital technology, the information storage furniture industry is still growing. There is no political power without broadcasting power, and no one has the authority of broadcasting without a reliable and closely co-operating political system.

Mike: In your performances, videos, actions and interventions you like to warm yourself with the word ‘revolution.’

Istvan: Now that I’m Istvan Kantor and I live in Toronto I’m more and more interested in revolution. As I told you at the beginning of my speech, I’m afraid that my revolution has failed. I was six years old when the Hungarian Revolution happened and I wanted to be part of it. I slipped out from the air raid shelter and pointed my toy gun at a Russian tank from behind a tree. The tank stopped and a soldier jumped out. I ran back in the house and hid in the dark while Russians surrounded the block and looked for the boy. There were lots of little boys then playing heroic revolutionaries. I kept playing it throughout my life. As a result I was kicked out, evicted, banned, deported, arrested and jailed. Ever since my arrival in Toronto, my life has centered on gentrification. Toronto is a capital of gentrification. It’s a very trendy subject here. For many people it means the upgrading of old neighborhoods through evictions, building demolition and the relocation of people against their will. For others it means the victory of real estate, luxury homes, new businesses and higher profit.

But gentrification is not only about the city and its neighborhoods. It is about people’s minds, the way we live and think. Everything has been gentrified, not only the neighborhood. The arts have been gentrified: the museum and galleries. The libraries, theaters, parliaments, the streets, subways, police stations, hospitals, the church, the beaches, the train stations and airports; they are all gentrified. Gentrification couldn’t happen without broadcast technology. Broadcast technology is the driving force of gentrification. It’s already been quite a few years since we’ve been staring at those shiny, bright, glossy, friendly, pulsating displays. Their hypnotic, shiny power is undeniable. Shinism rules. I’m not telling you anything new here. We live under the dominating control of broadcast technology and call it freedom.

Mike: While architect Frank Gehry was busy recasting the Art Gallery of Ontario into a postmodern tourist destination, you made them a unique offer.

Istvan: Why do you think the AGO is building a 300 million dollar façade? It will be a monument to shinism, a gigantic shiny screen made from titanium and glass, a glossy surface of command and control. It will pull people inside like a magnet. And inside the gallery there will be more shiny art.

Why do you think the AGO didn’t want me to mix my blood into the new walls? I proposed that I would mix my blood and other people’s blood into the walls to create an invisible monument that pays tribute to the slaves of the arts. That pays tribute to those who lived and died for art. And for sex and revolution. But my blood is too dark and the AGO didn’t want my dark blood to be associated with their new shiny building. They want shiny art, like the new art of Damian Hirst. You know the famous British artist who recently made a human skull sculpture from 100 million dollars worth of diamonds? This sculpture will be exhibited in the most important museums of the world. And then it will be sold for 500 million or more to one of the honorary members of global gentrification.

Gentrification denies everything that is dark because it reminds them of the dark ages when there was no broadcast technology. Even dark chocolate is too bitter for them.

I wonder what happened to the 10 million dollar damage I caused in the Museum of Modern Art in 1988? I was charged with a felony for staining a Picasso with a few drops of my own dark blood. Even though they cleaned it up with some warm water and Q-tips, the museum claimed 10 million dollars damage. Being considered an anti-art artist, this 10 million dollars damage equals 10 million dollars worth of art or damage-art. If I can create 10 million dollars of damage-art with a few drops of my blood on a Picasso, then imagine how much more money Damien Hirst can create with the power of 100 million dollars worth of diamonds? It’s evident that art in a gentrified society means nothing else than the creation of money from money.

You can’t just mix together some dirt, dust, mud, blood, salt and water and call it art. The “prima materia” of today’s shiny art is money.

Mike: The digital revolution has converged so much sensory experience into a single platform: music, pictures and words are already swapped and shared. It seems only a question of time before we can expect our other neglected senses to find their place. Your work examines the consequences of this profitable digital shining in the body, which is being quickly remapped.

Istvan: I am a transmission machine, like everyone else. I transmit heat, sounds and voices. The intense processing of information generates lots of heat in my body. While my head is spinning, my cooling system also works hard. I radiate light, and all kinds of other signals, psycho-tronic, telepathic, extra-sensorial, and I also transmit biochemical substances. My information transmission becomes almost overwhelming during orgasmic function and almost incomprehensible during a revolution. During epileptic seizure the body’s information production surpasses all limits.

Transmission machines like me are independent units transmitting directly from one to another. Lately, with all the new technology furnishing our homes, we are also part of the global broadcasting system. We are the ones who pay the rent to the techlords and keep the Rentagon in business. We are feeding the parasites so they can parasite us even more. It’s a global system of higher technology that operates through broadcast imperialism.

During the 80’s, I lived in Montreal and New York at once. It meant lots of traveling between the two cities. I usually took Czechoslovak airplanes. It was cheap, only $79 for a return flight.

On the plane they sold bottles of vodka for only $1. And this wasn’t all. The plane often shook a lot and because the seats were made from metal the shaking was even more pronounced. Everyone had a fear of death that produced tons of adrenalin in our blood. We were all totally excited. Today the seats are very comfortable, duty-free items are expensive, and there is a glossy, hypnotic screen in front of everyone obligating us to constantly stare at shinism.

The only time when I get away from the gentrifying shiny waves is when I’m in the park doing my daily exercises. I do yoga, stretching, push-ups, sit-ups, chin-ups. I also run, sing, pray and meditate. I try to do it for at least two hours every day. I go to High Park or Trinity Bellwoods when I’m in Toronto. In New York it was the East River Park, in Montreal I went up to the mountain. When I’m on the road I always look for a park right after arrival.

I have a prayer: Anyu, Nagyi, Kati, Apuko, Apu… Anyu is my mother, Apu is my father, Nagyi is my grandmother, Apuko is my grandfather, Kati is my sister. They are all dead but their spirit is alive. I call and ask them to surround my body. I call other people as well, mostly artists I met when I was young. Robert Filliou, David Zack, Sari Dienes, Ray Johnson, Jack Smith, Andy Warhol, Joseph Beuys, Cassandra von Rinteln and others.

I ask them to protect me from gentrification and from becoming a shinist clone.

Well, I just bought a new iMac. It is one of the leading products of the current shinist technology. It completely seduced me and now it’s in my office. As I told you, I’m frightened and I’m ashamed of myself for being frightened. I’m afraid of becoming what I have never wanted to become. And that’s why I am frightened.

Mike: The subject of your semi-autobiographical videos is often the ecstasy of transmission. You use technological terms to define your daily struggle. With deadly aim you conjure new forms of confessional narration while paying tribute to the spirit of rebellion. Your videos often feature the Machine Sex Action Group and explore the socio-physical aspects of trans-kinetic ecstasy and the techno-orgasmic ambiance of high-speed information exchange through a site-specific, machine-cult performance focusing on robotic stimulation, desktop eroticism, office furniture-sex and cybersport ecstasy. Noise becomes discourse which then lapses back into noise.

Istvan: When I work on my videos I’m immersed in a delirious and revolutionary panic, especially inspired by the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. Romantic nostalgia for insurrection is served up with critical irony, and underscored with dramatic Neoist statements about today’s oppressive global broadcast system.

It’s always about my own living experience. For example in Ubergespenst/Superspectre (67 minutes 2006) I cycle through the city of Berlin as the main protagonist, looking for collaborators. That’s basically my real life. But I also travel through an imaginary world populated by spies and rebels. My Berlin is an exaggerated, super-noisy, hyper-decadent, ultra-unstable and over-distorted version of the city. I produced this video between August 2004 and January 2005 while I was artist-in-residence at the Podewil. I was surrounded by great Berlin-based artists like Canadian dreamstar Peaches, Russian performance artist Elena Kovylina and the Berlin Neoist Faction of the Machine Sex Action Group.

I pretended to be a director looking for new talents for a spy flick. I lived this role and captured it on video. I absorbed my everyday reality as a fiction while narrating the story of a revolution. I carried red books and made it look like I was constantly followed by counter-intelligence agents. I lived the paranoid role of a yogi-insurgent-robot on a mission plotting against the BIA (Broadcast Imperialism Agency).

Everyone I met was recruited to become a member of this Neoist rebel group. The city was transformed into a stage of oppression and therefore a center for insurrection. I like to compare revolution to the ecstasy of transmission, or to be more exact, to reclaim revolution as “body machine transmission versus broadcast transmission machinery.”

Mike: Blood, fire, noise, machinery, convulsion and arrests: these are the most characteristic elements you use to provoke audiences. While your ideas are constructive, your practice revels in the joys of taking things apart. Can you talk about the art of destruction?

Istvan: I use different elements of assault and gestures of vandalism in my work, like the demolition of monuments, the defacing, burning and breaking of objects, the wrecking of furniture, the splashing of blood on museum walls, the making of unbearable noise via excessive and risky body actions which have been expanded with the use of scrap metal objects and furniture robots. The Art of Destruction is very poetical and post-monumental, exploring the subject-in-ruins with demolished arguments, wiped out symposiums, decaying historical documents, crushed events. It might sound disappointing for you (and for me) that I’m still involved with such a recuperated and discredited form. But I basically don’t intend to destroy anything. I would like to keep everything as it is. I like to accumulate things. I don’t even want to touch anything, just watch and observe. But even pleasing inactivity can become an act of vandalism that radically destroys the obstacles of creativity. That’s what I call Fuckoff-Revolutionary Machinery.

For a recent performance event in Toronto I did something I haven’t done for a long time: I stayed almost completely motionless for the duration of an event, holding an empty cookie jar. I have done very static, durational performances in the 70s and early 80s, always focusing on one simple gesture, like a yoga exercise amplified by time. Living Sculpture (Budapest, 1974) and It was very nice to see you and talk about revolution (Montreal, 1979), are a couple of examples. I never really gave up that sort of “tableau vivant” expression but incorporated it as an element in my multi-layered pieces because a single gesture didn’t seem enough to demonstrate my idea of vertical expansion. I needed to explore simultaneity, confusion and decay, and I could only achieve that by integrating lots of layers of information in one work. In the cookie jar performance, That’s How I Want To Be Remembered (1998), I included ideas concerning the destruction of objects in a narrative form by explaining my gesture later in the evening. And finally I broke the jar. But the jar was already broken at the beginning anyway. I mean, theoretically, I didn’t really have to break it. On the other hand, in a timeless zone, it would have stayed unbroken even after the breaking. That’s why I propose that it’s always 6 o’clock, because only in a timeless zone can we keep everything as it is. 6 o’clock means vertical expansion, that is, the accumulation of everything at the same time. It is an idea that makes linear history obsolete and thus annihilates time and history. That’s what I call the theory of accumulation. Of course my theory is only a poetical proposal, but there is a British physicist, Julian Barbour, who confronts our inherited theories of time. He has been called time’s assassin. Barbour argues that we live in an eternal present, without past and future, where everything co-exists and we are all alive and dead at the same instant.

In this timeless zone of accumulations, the Art of Destruction (this decadent form of artistic refusal and negation) can only survive in its own ruins. It’s a mess of bloody shit, broken parts and confusion, like a compost. That’s why it can remain a very fertile ground for inspiration.

Take for example the Auto-Destructive Art Manifesto (1959) of Gustav Metzger, the piano destructions by Raphael Ortiz (60s to present), the monumental TV-destruction performance “Media Burn” by Ant Farm (1975), the spray-paint museum actions by Alexander Brener (1997) and Tony Shafrazi (1974), the giant mess rituals by Johanna Went (80s), the violent fuck-off transgressions of GG Allin (80s, early 90s), the horror-movie-style stage shows by Kembra Pfahler (80s) and Joe Coleman (80s), the orgiastic taboo acts by Carolee Schneemann (60s), Paul McCarthy (70s/80s), Otto Muehl (60s), Hermann Nitsch (60s to date), the vomit solos and sledgehammer attacks on objects by Jubal Brown (97/98), the TV destructions by Wolf Vostell (60s) and TV-image distortions by Nam June Paik (60s). Let’s not forget the cut-up novels and shotgun paintings by William Burroughs. Or the “Erased De Koonig” (1953) by Rauchenberg. The Dadaists destroyed all the words (10s), the Lettrists annihilated all the idols (50s), the Neoists (80s) eliminated originality. I have a publication entitled “A Guide to Art Vandalism Tools, Their History and Their Use,” an illustrated encyclopedia by Steven Goss. It contains information mostly about museum crimes, attacks on art works done with the use of hammer, scissors, ink, knives, paint, lipstick, guns, acid, spray paint.

Perhaps I could also mention the recent removals of statues and monuments in ex-communist countries or even the demolition of the Berlin Wall, not to mention the sledgehammer destruction of Confucian temples by Red Guards in the 60s. All these things, names and ideas are accumulating in the rubble of history of the Art of Destruction. This rubble is my living territory.

Everybody is using broken pieces of information found in the rubble. Some try to put copyright on them which is absurd, but, on the other hand, it creates another field of conflict where authority can be challenged through the maze of plunderground. There are various forms and methods of plagiarism. Something I (you) like to explore. Vertical expansion, or vertical reality as you (I) also like to call it, is an extremely contradictory field of theory where we can freely appropriate any ideas. We have to use a language that integrates everything otherwise it would sound completely fake and unrealistic, like a five minute stupid love song lie.

Yes, lies are only useful when they subvert reality. My mission is to provoke, confront, challenge the facts of everyday reality, time and decay. Two years ago, during the opening of my exhibition at the Black Black Gallery in Budapest, I was arrested and thrown in jail under totally absurd circumstances. All I did was a minimal performance that consisted of me sitting in a chair whispering to visitors about a new revolution I was about to start. I told them I was the spectre of Neoism?! and was able to transmit my ideas through telepathic means using a coat hanger antenna attached to my head. Someone called the police suspecting I was part of a religious sect, perhaps spreading the ideas of a Satanist cult. The police came and didn’t leave until they found a good reason to arrest me. Subverting reality invites retaliation.

Mike: When you were living in New York in the late 1980s, poor living conditions in the lower east side led to a creative flourishing in that area which you participated in, albeit on the fringes.

Istvan: Noise especially became important in my work during the second half of the 80s when I lived in New York and joined the Rivington School. The School operated in the Lower East Side and explored junk sculpture, scrap metal noise, graffiti, rebellion. I documented the School’s work in a super-8 film Anti-Credo (1987) that immortalized the construction and destruction of the Rivington School Sculpture Garden. Using an empty lot at the corner of Rivington and Forsyth, the School created a giant scrap metal maze that became an important architectural and artistic site in the local landscape. The Garden became the victim of development and was destroyed by a wrecking crew hired by the city.

Development is definitely based on the act of vandalism. That’s what linear history tells us. Every city and every place that has vanished from history first had to be destroyed. And usually not by the elements of nature but by people, by wars arising from human conflicts that were conditioned by emotions, culture, education, religions, poverty and the struggle for power. That’s what interests me the most: power and authority in technological society. When I talk about technological society I start with the walls of Jericho, the tower of Babylon and the cuneiform tablets of Nineveh. When I look for material in a junkyard I feel like I’m standing on the ruins of Babylon. It sounds like a hallucinatory experience, but again, I’m using the theory of accumulations and for me the expansion of time is vertical. The rubble of history is mixed with the ruins of present decay.

That’s basically the subject of my video trilogy, The Anti-Cities, that includes Jericho (1991), Babylon (1994) and Nineveh (1997). I also gave my children the same names. I am completely obsessed with vanished cities and the theoretical function of the decay of technological society in my everyday life. It seems like I stepped beyond the “society of the spectacle,” crawling under the ruins in order to focus on the spectacle of noise and decay. The ambient surface of ruins — that superficial territory of everyday life — is only visited by tourists and archeologists, and has never been explored by anyone else, untouched even by the Situationists.

This is the territory of children. Every child knows that destroying things is lots of fun. Just watch little kids at the playground, in the sandbox. Most of the time when they build a sandcastle they already know that in the end they will destroy it. It’s a collective ritual repeated over and over again. It’s a mirror of history. That’s why we make sandboxes, so that children can learn how to build and destroy, how to play with the elements of creation and destruction, and combine them.

Destroying sandcastles, breaking toys, stabbing teddy bears, tearing pages from books, scribbling on walls, turning over furniture, etc, are part of the everyday events of children’s life. It is part of a constant play that we can call the art of childhood. Interestingly enough, such artistic acts that involve the use of destruction are often criticised for being childish, juvenile, immature. The Situationists were afraid of anything that could be criticised as childish activity. We are not. We know that we get our best ideas when we are children. So we try to remain children. You can’t criticise a child for being childish.

Mike: Your early work is rooted in mail-art activities. Correspondence and direct communication between networks of artists was one of the driving forces of artistic experimentation in the 70s and 80s until the internet was widely practiced.

Istvan: Basically, I did everything when I was six years old. I have a collection of defaced items including family photos with my pencil marks and ink spots, and my father’s official documents damaged by my graffiti. Whatever I have done later, I can trace its origin to my childhood. My Neoist Passports (also know as Lost Passports) are good examples. I circulated them through mail-art networks in the late 70s, asking everyone to make marks in them. They were my official travel documents from Hungary, the red one was for Communist countries in the Eastern Block and the blue one for the West. I kept using the blue one until my arrival to Canada (1977), though it was already filled with notes, signatures, rubber stamps, drawings by mail-artists. From David Zack to Cavellini via Anna Banana, Buster Cleveland, Dr. Al Ackerman, Art Lover, tENTATIVELY and many others. Then I got a new brown travel document or homeless passport which I used for the next few years and again I asked artists to sign it. I considered their signatures as visas. Among the visa-signatories were John Cage and Robert Filliou. This passport was stolen from me in New York in 1981.

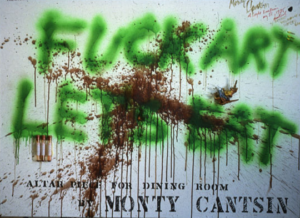

Both the Monty Cantsin open-pop-star project and NEOISM?! were part of the mail-art phenomena. Mail-art was the perfect vehicle for spreading the ideas of Neoism?! through short sentences like “Anyone can be Monty Cantsin,” or “Do everything in the name of Neoism?!.” The official, post-modern, institutional art world could never swallow such anti-theoretical, immature statements. Neoism?! was designed to resist and reject established art and museum culture at all costs. It was evident that such shit-shows like the “Bring Your Monty Cantsin(s)” (1988) group exhibition I organized in collaboration with the Rivington School, for example, had to be held at such anti-establishment places like the Crystal Palace, a filthy, run down bar in New York’s Bowery. Though this was not a mail-art show, it reflected all the characteristics of mail-art mixed with the junk-art aesthetics of the Rivington School.

Mail-art was an anti-art form heralding the idea of interactive direct communication that annihilated the old fashioned creator-artwork-public aspect of art and turned everyone into artists. Adding ideas, notes and signs to each others works was a regular method of mail-art actions. Mail-artists eliminated the need for art galleries and museums, turning the postal network into an ongoing exhibition. They often got into trouble with authorities for circulating art because of material that was considered sexually explicit, obscene or politically subversive. This anti-institutional, provocative aspect of mail-art corresponded with theories about the art of destruction. Mail-art was a hothouse for new, confrontational, radical ideas.

Most of my projects in the 70s and 80s were connected to mail-art. There are many important names attached to this period, among them David Zack and Dr. Al Ackerman. Zack died in 1995 after spending a few years in prison in Mexico. His involvement in nut art, communication art, mail-art and then in Neoism is something that should be researched and perhaps saved in a book. Most of his work was destroyed by the circumstances of his chaotic life. He and Ackerman were instrumental in training me to become a subversive. This was in 1978 in Portland, Oregon, at the Portland Academy, that was basically the living quarters of Zack and Ackerman, and quickly extended into clubs, bars, churches, abandoned buildings, the streets, the Smegma house and some non-profit art centers. It was a very intensive situation with constant brainstorming and experimentation. From Portland I went back to Montreal and initiated Blood Campaign, a work in progress since 1979. The aim of the Blood Campaign is to finance the operations of the Neoist conspiracy by selling my blood as an art object.

Mike: After all this destruction, what is left but the ruin of art itself?

Istvan: I had a constant dialogue in my head about the final end of art, adding new ideas to the ongoing annihilation of art that was necessitated by the equation between art and life. That’s what I demonstrated in Refus (1980/Montreal), an anti-installation/performance that took place at No-Galero (my own apartment). I sat on the toilet in my bathroom all day long and typed the same phrase over and over again “No Performance Pas.” The bathroom door was open but I covered it with a semi-transparent, golden mylar sheet, so you could see me only when I turned the light on inside. I did this for about two weeks. The end of the 70s and the beginning of the 80s were extremely important for me. I was completely seduced and activated by the “life is art, art is life” and “everybody is an artist” theories I learned from David Zack, Joseph Beuys, Robert Filliou, Ray Johnson, Sari Dienes. I had to show that I didn’t make art, I lived art and so the audience was not necessary. The mail-art network was a perfect and very fertile ground for this kind of discourse. But by the end of the 80s, mail-art had degenerated into routine shows focusing on crafty exhibitions that no longer served its original function of non-institutional, direct communication. I sent back insulting letters to all the mail-art invitations I received in order to subvert the weakening network and to put mail-art back into revolution. But the response was very disappointing and eventually I gave it up.

Mike: You have been a tireless defender of Neoism.

Istvan: I created propaganda for Neoism through mail-art and apartment festivals. The apartment festival concept, “a cheap holiday in someone else’s misery,” immediately took off and it became an international method to spread Neoism. Events were held in Montreal, Berlin, Baltimore, New York, Toronto, Novi-Sad, Amsterdam, Paris, London, Tepoztlan, Budapest and elsewhere. Meanwhile, to get back to our previous subject, I also executed a series of Supper performances under different circumstances and mostly in different cities. Hallowmass Supper/Montreal, Seizmik Supper/Ukiah/CA, Counter Supper/Portland/OR, Midnite Supper/Vancouver/BC, always involving blood and mail-art. Police interventions, audience fainting, gallery censorship and shaking nurses conditioned these events.

I was on the road full time, traveling from city to city like a missionary, convincing people to join Neoism and performing wherever and whenever I could. In Ukiah (CA) my performance was stopped by the intervention of a nervous hotel-detective who couldn’t handle the blood-kiss part that involved mouth-to-mouth blood transfer between myself and another male performer.

In Vancouver, an inexperienced nurse punctured my veins some 16 times while trying to draw blood from my arms. Several members of the audience feinted. One of them was taken to the back room to take a rest. He probably didn’t know that it was my change room. When I went back after the performance, naked, my dick taped between my legs to achieve an asexual look, bleeding from my punctured arms, my mouth and face bloodied by the final blood kiss action, he feinted again and was hospitalized. These obscure, characteristic episodes formed a ring of legends around Neoism and conditioned the ambience of further events. Of course, I was very conscious about the usefulness of scandals and police interventions helping us to gain access to the media.

Mike: “Accumulation” is a key word in your capital critique. Past, present and future occur at the same time. As your often repeated performance slogan runs: It’s always 6 o’clock! You posit a vertical reality, as non-linear as an edit program, where ideas gather and adhere. One amongst your never-ending, long term projects is the Blood Campaign. Can you describe these many actions taken in the face of this information surplus.

Istvan: Blood Campaign has grown into a monster project involving hundreds of performances, each of which incorporated the act of blood taking that was usually done by professional nurses, doctors or by myself. My blood performances were not orgiastic and theatrical taboo rituals like the happenings of the Vienna Actionists, but, rather, demonstrations of the clinical act of blood taking. It was either very short, clean and ironic (sometime even funny) or painfully long, really bloody and dead serious, mostly depending on the performance of the nurse or doctor. During the blood taking I usually encouraged the audience to ask questions concerning my work, life, ideas.

The moment of blood taking creates a clear intensity that is often uncomfortable for the audience and because of that it is a perfect situation for making statements. When you sit on a chair at a talk you don’t have to focus on what you see and hear. The act of blood taking destroys the comfort of non-participation and draws spectators into the action. Afterwards I use the blood in different ways, for instance, to make soups or give blood kisses, or I splash the blood on specific objects, like t-shirts, books, newspapers, art works, on people, on the floor, on the sidewalk, on museum walls, into the fire. I splash it on a pregnant belly. I drink it, or spit it on somebody’s body.

I stick a blood tube into my anus and then go up in a yoga position so the blood can flow from the vial right on my face, to my mouth. I smear it on something, on a pigeon’s white feather for example. I usually keep a vial for my own collection and try to sell another one to an art collector. I make people play blood-lottery. I donate my blood to the Red Cross. I fry it, mix it with rice and eat it. I let it drip on a hot plate. I use the blood tube for sexual gratification.

The blood-x splash made on the walls of museums, usually between two artworks, is one of my trade marks. I also like to remember the more obscure actions at smaller places as well, like the one I have done on the wall of a chapel in Transylvania, or the one at CBGB gallery in New York, or on the wall of a building in Budapest, or in Sarenco’s gallery in Italy, or in abandoned buildings, in clubs, in my office, in a bathroom, in living rooms, etc. Many of these actions were executed in front of a public, but often they were witnessed by only a few close friends. I usually use empty white walls to make my blood paintings and if some drops fall on a Picasso or a Rauschenberg, like they did at the Museum of Modern Art and the Ludwig Museum, it was not my intention. My intention was to give a gift to the museum that is basically impossible to accept. Of course I always asked them to keep it until it becomes meaningless, obsolete. And of course they never accepted my donations, quickly eliminating them. The walls are washed and painted, the floors cleaned. Should I say that by cleaning up the gallery they vandalized my vandal’s work? That would give them too much credit.

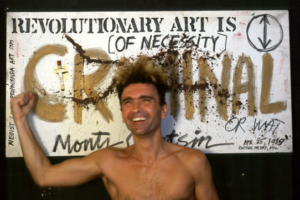

I’m using extreme situations to trigger a very strong reaction, to exactly define my theory and practice. I have to create a crisis in order to present the cause. The blood-x marks the nerve center of this crisis around which people’s opinion circulates; the reality of laws, politics, spirituality and sexuality intertwine to create a chaotic, convulsive and sometimes coherent pattern. That’s my working method. I learned that to become an artist, first you have to become a criminal.

Mike: Why did you leave Montreal?

Istvan: In September, 1992, a final decision was made by the Rental Board of the City of Montreal that forced me to move from my apartment, known as the Neoist Embassy, located at 1020 Lajoie, Outremont, Québec, where I lived for more than ten years. My eviction was the result of investigations carried out by city officials after the landlord’s complaint of blood rituals, sex orgies, Satanist ceremonies, neo-Nazi gatherings, destruction, etc. Led by my landlord, investigators entered my apartment several times while I was away. They searched my rooms and took documents to prove the landlord’s accusations, including a leaflet that contained an artistic statement about the Blood Campaign. Written with irony and humour, it was printed in the form of a publicity flyer for an exhibition/performance that took place at Le Lieu, in Québec City, in April, 1991. It included the following text: “Why would you dream about spending 80 million or more on a used Van Gogh when you can have a brand new, fresh blood painting of Monty Cantsin for free?”

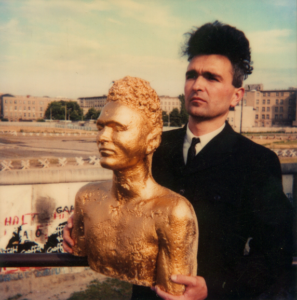

After a year of legal battles I had no other choice but to accept the decision of the Rental Board of Montreal and get the hell out of there. To make a final statement, I turned my eviction into a “Retrospective Exhibition.” Besides showing my personal belongings and original works to a video camera, I incorporated falsely identified cardboard boxes reproducing the landlord’s accusations, wearing such signs as “Satanist ceremonies,” “Vandalism,” “Sex orgies,” “Blood rituals,” etc. I also made sure that certain objects of my ill-fated reputation, like my series of blood paintings, my own gold bust, or the gold cage of my rats, for example, were part of the “retrospective.”

I have never really thought about vandalism until I read in a newspaper that what I was doing was nothing but vandalism. That made me laugh, and at that moment I realized that the best course was to absorb it as a useful term, recognize it as my own, and employ it without being afraid of it. So I decided that I should not defend myself against the accusation of “nothing but vandalism,” but, on the contrary, I should defend vandalism as the ultimate act of creation. That became the basic subject of my 1993 Monument Temporaire installation presented by CIAC in Montreal.

On the last day of the exhibition I destroyed the entire installation with the help of a wrecking crew, using axes, crowbars and hacksaws. This was the perfect situation to talk about all the essential elements and necessary circumstances of my work. It was basically a lecture illustrated with live action. This is a kind of presentational form I like to explore because this way you keep close contact with reality, with the actual moment of the performance. That’s exactly what happens when I do a museum intervention, it’s like an illustrated talk involving the guards, the public, the police, the curators, the director, my co-conspirators, the media; basically the whole system of art and society. Although my CIAC destruction was not an illegal action, the execution itself created a very intense atmosphere that subverted and overturned the official context, creating chaos and confusion among the public and lots of distress for the organizers.

Mike: Do you have a final thought, a Neoism we can snack on as we make our way to the end of the world?

Istvan: I think this new epoch will be characterized by a manifesto produced twenty years ago where I blackened out an unwritten text on an empty page. Actually, it wasn’t completely empty. I had written the title “Neoism Manifesto” (1979) and one short sentence, “Neoism has no manifesto.” Then I made black marker lines, simulating the idea that I had blackened out the rest of the text, and then signed it. But, as I said, what I eliminated was actually an unwritten text on a virtually empty page.