Protest Songs: an interview with John Greyson (2012)

John: I was born in Nelson, British Columbia. My dad was going through grad school and taking alternate years off to support the family, so we moved between Nelson and Eugene, Oregon. In 1964 he got a job at the University of Western Ontario that relocated us to London when I turned four. We were a large family by today’s standards. Catholic. I was the middle child with two brothers and two sisters. There were no home movies of any description, but we had a war-era slide projector, and the shows were magical. Mom and dad would narrate family histories over the smell of burning dust. Owing to my parents’ principled, Vatican 2-Catholic-enviro-peacenik beliefs, we didn’t own a TV until I was eleven. There were no guns allowed, of course (though bows and arrows and slingshots were fine — as long as they were homemade!). One of my earliest erotic memories is going to the drive-in and seeing Walt Disney’s Swiss Family Robinson (1960). There’s a fantastic scene where the cute eighteen-year old son wrestles a big snake. Very formative.

Mike: You joined the swim team.

John: Just for a few years. We moved to Wales for a year when I was twelve because of my father’s sabbatical. I was London’s fastest breaststroker in my age group, for one oh-so-short summer, but then the next year I grew six inches and became a proverbial string bean. I was on the team with Peter and Maureen, my older brother and sister. We’d go to the YMCA after school and then bus home. After practice our long hair (hey, it was the 70s) would freeze solid, and the industrial strength chlorine ensured at least an hour’s crying from tomato red eyes.

The first three years in high school were at Catholic Central, a very ordinary downtown slumberfest. Halfway through grade eleven, I moved down the street to Beale Tech which was a wonderful, technical high school with a legendary art department. My favourite class was with Tisch Scott who had decided that art history began in 1960. We’d study Chris Burden one week and then make our own performance works and video art the next. She’d never actually had a chance to see the real thing, she’d just read about it in Artforum. She would bring in articles about Seedbed and say, “Isn’t this exciting? Vito Acconci’s lying under the gallery floor jerking off…”

We borrowed 3/4” portapacks from the Television Arts facility. I didn’t know you could edit, so those early tapes (really just experiments) are all in real time. There’s one I’m still fond, the rest are long gone. My video restages a formal family photo that was taken of us all in 1974 on the living room couch, only in this video version everyone is given a nonsense script to read. Their characters and relationships emerge in ways that have nothing to do with what they’re literally doing. It’s not the only footage I have of my mom, but it’s some of the choicest.

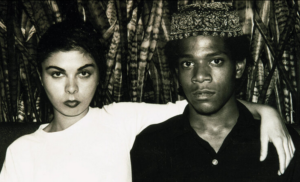

The rest of the school thought we were freaks and they were right. All the rejects and punks and queers wound up in the art program whether they could do art or not. On Fridays we would convene at the Blue Boot, a downtown Native bar that booked local punk bands on weekends. The Boot, and later, the Cedar Lounge, were our local London intersections for art and punk. There’s a few people I still see from those days; Rebecca Garrett, Duff Campbell and Ian Duncan in particular, and also Ben Smit and Suzanne Mallouk. Suzanne dated Nazi Dog’s bodyguard so I got to tag along to Viletones’ practices. Then we both moved to New York in 1981, and she hooked up with this guy called Jean-Michel Basquiat. She was the girlfriend muse famously celebrated in a book called Widow Basquiat: A Love Story (2000). She’s a psychiatrist today.

Suzanne Mallouk and Jean-Michel Basquiat 1981. Photo © Duncan Buchanan

We shared a dare-we-say universal feeling of I don’t fit, I need elsewhere. When I moved to Toronto I was still lacking one credit for grade 12. I think I could have talked my way into the Ontario College of Art because they were pretty loose, but I wound up choosing Art Sake instead. Art Sake was created by a group that broke away from Three Schools in the 1970s. A lot of the Isaacs Gallery artists wound up there, abstract painters like Gordon Rayner, Graham Coughtry and Dennis Burton. Though of that crowd, Diane Pugen was the only one who took teaching seriously. The others would arrive wearing their hangovers and tell us to paint the life model, occasionally offering remarks like, “Too much blue.” I wound up not quite finishing because the stuff I was interested in was performance and video and that was happening in artist’s spaces downtown.

Queen West hadn’t really begun, though the Peter Pan Restaurant had just opened and planted the flag. In 1978 Art Metropole moved to Richmond Street, and a year later A Space and Trinity Square Video arrived around the block, in what is now the City TV building on Queen Street. A Space’s mandate had moved them out of their legendary space on St. Nicholas to become a gallery without walls, staging events at satellite spaces around the city, dematerializing the art institution at the same time as the art object.

I paid the rent supervising lunch hours at Alpha, an alternative grade school and also picked up some nude modeling gigs at OCA and Art Sake and the University of Toronto’s architecture program. Then, in the spring of 1979, a government-sponsored youth employment program was announced, and I approached the art magazine Centrefold (that later became Fuse) offering my services (such as they were) for free for four subsidized months. The magazine had moved from Calgary a year earlier, and Lisa Steele, Clive Robertson and Tom Sherman were the co-editors.

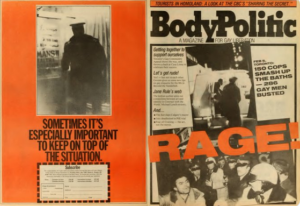

There were several other artists’ publications at the time — Impressions, Impulse, File, Only Paper Today, and Incite (a few years later) — whose priority was to publish original works by artists. Magazine-as-museum, magazine-as-venue. When Centrefold was redubbed Fuse, it prioritized criticism which looked at the art scene through the prism of social justice. Just before I arrived, they had published a special issue on The Body Politic’s obscenity trial and state censorship, and the emerging idea of artists in solidarity with political/social communities, in this case, a gay community under attack. The case concerned the publication of a Gerald Hannon article called “Men Loving Boys Loving Men,” which is still worth reading today. It’s a very subtle and nuanced examination of man-boy love in which he interviews and spends time with a couple of boy lovers and their boys. The article arrived at a cultural moment of global child porn/pedo hysteria, accompanied by Anita Bryant’s anti-gay crusade south of the border. A moral panic held the United States in its sway, and Gerald and The Body Politic wanted to fight back and contribute something complex to these debates. For their troubles, they were charged with distributing obscenity through the mails. They were found not guilty and free speech prevailed, but the crown appealed (twice) and there was much collateral damage. It’s pretty much accepted that Toronto mayor John Sewell lost his bid for re-election because of his appearance at a fundraiser for The Body Politic. While he had critics on many issues, many felt it was his principled stand on freedom of expression that sunk him politically. And for those who would like to believe that there was an easy divide between the gay Marxist politicos at CEAC, and the postmodern glamour squad on Queen West, it’s noteworthy that General Idea, the Clichettes, Clive Robertson, Lisa Steele and a clutch of other Queen West luminaries performed at this fundraiser, not the CEAC boys.

Mike: Did you know what was happening at The Body Politic?

John: When I joined Fuse in 1979, our typesetting was being at The Body Politic, so I got to know various staff and collective members, and started pitching a few small articles for the paper. The most interesting was an experimental piece of image-text fiction entitled “The Box Boys,” a sort of post-punk, performance art deconstruction which puzzled most readers and collective members alike.

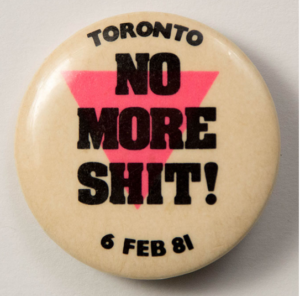

The Body Politic trial divided Toronto’s fledgling gay community, with many regarding the newspaper as a radical, divisive, non-representative rag. A year later the baths raids changed everything. They occurred on February 5 1981, when 150 Toronto police officers did a midnight raid at Club Baths, the Romans II Health And Recreation Spa, the Richmond Street Health Emporium and the Barracks, arresting 286 men. It was the largest mass arrest in Canada since Trudeau’s War Measures Act in 1970 and it was met with immediate outrage. Meetings were held the next day at The Body Politic and a call to gather that night went out on the streets. 3,000 people marched, and two weeks later there were more. It was one of those extraordinary moments when everyone (or at least, most everyone) saw things very clearly and did the right thing. We marched illegally to the police station and then to Queen’s Park. It wasn’t quite a riot but we were definitely rambunctious, screaming “No More Shit!” San Francisco had burned police cars earlier that year when the Dan White verdict was brought down, White being the killer of Harvey Milk, California’s first openly gay elected official. We performed a more polite version, but nevertheless there was real rage. I think the police completely miscalculated the shifting place of the queer community within the larger society. Their attitude was, who is going to defend a bunch of guys having sex in a bath house? In fact, there was much broader support than they (and even we) anticipated. Margaret Atwood typified this shift when she appeared at a demo and coyly asked, to laughter and applause, “Why on earth would the police be opposed to cleanliness?”

The Right to Privacy Committee was formed, and there were a lot of demonstrations and fundraisers and marches, as cases made their way through the courts. Some of the men caught were out and queer and proud, while others were married and closeted — and everyone needed support. We wanted to give these men the sense that they’d done nothing wrong. What was wrong were these arcane laws that had to be overthrown. The cases were fought and mostly thrown out.

The grassroots committee making up The Right to Privacy Committee involved a lot of people who had worked to defend The Body Politic, including Tim McCaskell. Tim and Richard Fung were living in a communal house on Seaton Street, and their housemate George Smith (who was in one of my very bad early video performance pieces) was one of the main organizers. To its great credit, the Committee also started doing work around men being entrapped in parks and public washrooms, both with video surveillance and undercover cops. In the broader community, while there was a great collective will to defend the men arrested in the bathhouses, there was little solidarity expended on defending men caught in the toilets. Why was that? These questions, and the invaluable work of the RTPC, inspired a body of work about the policing of public sex in Ontario that included The Jungle Boy (15:30 minutes, 1985), You Taste American (24 minutes 1986) and Urinal (100 minutes 1988).

Mike: What is video art?

John: Ha! I guess I can talk about some of the strains that touched me directly, and kept me up at night. First, a process-oriented practice that came out of minimalist sculpture traditions and was in lock-step with a cinema of duration. Vito under the floor et al. Then, a narrative-based Canadian school where duration met storytelling: Video Cabaret, Vera Frenkel, Colin Campbell, Lisa Steele, Rodney Werden, Susan Britton, and to some degree, General Idea, Paul Wong, the Western Front. Punk cheating on Baudrillard with Douglas Sirk.

Mike: How was video presented?

John: Work was shown almost exclusively in artist-run spaces on large Sony monitors: A Space, Trinity Square Video, Art Metropole, Mercer Union. There would sometimes be as many as fifty people. The artist was usually present, and there would be a question period following a single screening. Video installations had receded somewhat in that period and single-channel tapes and one night (screening) stands were the norm.

Mike: How did you get started making video?

John: When I got to Toronto I joined Trinity Square Video right away. Trinity is an artist’s co-op, founded in 1971 by a group of activists in order to provide cheap equipment to communities and artists. It epitomized the early video art marriage of social change and artistic expression. I definitely should have taken workshops, but I decided to plunge ahead and just make things instead. White balances are for sissies. I did some performances using video as a central component; they were my first attempts at integrating gay leftist content into an avant-garde practice. The work grew out of the debates concerning The Body Politic and the bath raids, but the videos used meta-fictional techniques and appropriation, I wasn’t interested in making documentaries or fictional versions of real events. Video art was a way to approach the actual ideas at stake, but without getting bogged down in the characters and facts and drama of what actually happened. (For years on the wall above my desk I had taped up a 1959 drugstore paperback cover of a novel called The Gay Outsiders, which had as its marketing slogan: “Realism traps the homosexual in an in-between world of heartbreak and deceit.” You said it, Mary!

In 1980, I created an eight-hour duration performance at Harbourfront (curated by Robin Collyer), that tried to occupy the container of a live radio show. In Kingston I staged a video “church service” that saw competing groups of gay Catholics hold hunger strikes in order to gain slots in the Sunday mass schedule. The men were seated on one side, women on the other. It was incredibly convoluted, featuring a badly shot and conceived video narrative that became The Visitation (40 minutes 1980). Once again, the performance borrowed the format of a radio show, with news interruptions between songs occurring every few minutes. I did another performance at the Paris Biennale that indulged fantasies about gays in the military joining a Lavender Regiment, which became The First Draft (40 minutes 1980). While it’s pretty much unwatchable, the content is intriguing given the emergence of gays in many militaries globally, the ensuing “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” debates in the United States, and the homo-normalization of queers within a post-9.11 pro-war consensus. In 1980, the idea that there could be a gay division within the military seemed beyond the limits of the possible. The co-optation of sexuality and radical queer politics in the name of war and defending the state has all come to pass thirty years later. Pretty strange.

Mike: Can you talk about the solidarity work you did with the Nicaragua Revolution, that saw US-backed, right wing dictator Somoza overthrown by a people’s guerilla army in 1979? You joined a couple of video collectives and produced several documentaries.

John: In New York (1981-83) my video work was channeled into collective creation. The first project was a documentary about the War Resisters League action in 1982, the largest civil disobedience action for peace in US history. The second was about the reconstruction of rural Nicaragua. I spent the summer in Esteli in the war-zone, with friends Eric Shultz and Mary Anne Yanulis, interviewing villagers and Sandinistans about the optimism of the revolution and the coming contra-war.

Mike: Was there a sense that you were building a body of work inside a community?

John: There were a bunch of communities. I became very active in the gay activist community, and was really excited about the idea of the avant-garde in relation to queer activism. It wasn’t an easy fit — many at The Body Politic, for instance, still thought that gay culture consisted of Donna Summer, Barbara Streisand and Judy Garland. Then there were a bunch of us, including Tim Guest, Andy Fabo and Alex Wilson who was the culture editor at The Body Politic, who tried to shift the debate, and insist that queer artists were doing contemporary avant-garde work that engaged gay issues in relevant ways.

Mike: You had an important encounter with the work of Stuart Marshall.

John: He was a gay video artist from England, and was a huge influence because more than anyone he was engaged in both activism and theory, taking up questions of representation and sexuality via the radical deconstructions of television forms. Stuart would inhabit existing genres and turn them inside out.

Mike: You were together with Colin Campbell from 1986-1989.

John: He was by far the biggest influence in terms of art and life. Here’s a sketch from an afterword I wrote after he passed. “In the early eighties Colin Campbell was professor in residence at a little-known, yet extremely influential atelier: The Woman from Malibu’s Video Art Academy and Finishing School (Yonge Street Campus, upstairs from the Athlete’s Foot outlet). Ten easy lessons, non-accredited. No tuition, just intuition. No transcripts, just trans-sex. No prior experiences necessary, just start making tapes… or martinis. Between classes he was variously producing Modern Love (1978), Bad Girls (1980), He’s a Growing Boy, She’s Turning Forty (1980), Dangling by Their Mouths (1981), Conundrum Clinique (1981), White Money (1983). Lessons invariably overlapped with production. As did life.

Lessons

1. Turn last night’s dinner conversation into tomorrow’s dialogue. Colin’s scripts were flagrant collages of his pal’s best bon mots and intimate confessions. We’d emerge from screenings both chagrined and flattered by such blatant thievery. And grateful, because he’d tightened our timing, improved our delivery, deepened our meanings.

2. Make nightclub sets from couches and lamps in the studio. In turn, make couches and lamps from display racks that the Athlete’s Foot outlet downstairs left in the alley last week. The same corner of the loft, the same Athlete’s Foot “couch,” and the same lamp are featured in every tape he made in his place on Yonge Street, yet they always seem new and different. Five-minute makeovers were effected with a swath of fabric, a coat of paint, a backdrop of pastels on coloured paper.

3. Shoot with one or two or no lights, one or two or no crew, one or two or no backdrops, but always two or more drinks. He was hopeless with tech, yet he’d find his unique way to make it work. His best shots were sometimes when he forgot to turn the camera off. His best edits were often the ones he made by mistake, his best montages the ones he slammed together deck to deck.

4. Assimilate high theory and low humour by osmosis. Colin never read Foucault and Deleuze; he didn’t need to, he had friends who did. He just inhaled the gist over dinner, unerringly extracting the curds from the whey. He shoplifted from both sides of the culture promiscuously: headlines, Eve Sedgwick, gossip, trash talk, Barthes, then transformed his theft into unassailable ownership. His tapes are very op-ed, of their moment, a catalogue of tabloid obsessions and current debates. He found uniquely personal ways to respond to political crises, be it censorship or AIDS. Though he was appalled by injustice in any form, his interventions were never from the soap-box; he refused the rhetorical in favour of ironic commentary.

5. Write roles for old friends because they need cheering up, and for new friends because they need unpacking. Video as socialization: who cares if friends can’t act? The raw, jarring, awkward and at times excruciating gap between the person and the performance was the space he zoomed in on. Colin was allergic to verisimilitude, fascinated instead by the vulnerability of self-consciousness.

6.Monologues are more interesting than dialogue because they don’t pretend to be natural. In Dangling by Their Mouths he quotes the dead-mother monologue from Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying at length. In tape after tape he returns to Faulkner’s strategy of competing monologues, different characters confessing their versions and secrets and poor little poems to the camera. The first movie we saw together was Fassbinder’s In the Year of Thirteen Moons. More than anything, this film helped me understand the art that Colin was chasing, embracing, creating. The art of declamation, the art of melodrama, the art of tableau.”

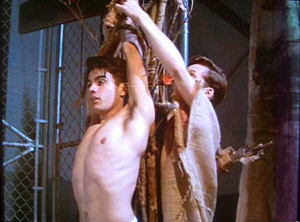

Colin’s working method was the thing that made art possible. A crew of one or two, home made props and costumes, and a reliance on sampling genres combined with a pastiche aesthetic. Colin was The One. While I’m mortified by my performances in four of Colin’s tapes, I achieved revenge by casting Colin in four of my own (The Jungle Boy, You Taste American, The ADS Epidemic, Urinal). You Taste American was made in 1985, first for the dance-performance festival in Montreal, Moment Homme, and then at the Workman Theatre in Toronto for an A Space series. Colin, Stephen Andrews, Dougie Durand and I performed in front of slide projections and audio recordings (still a few years before video projection became available). The fragmented narrative was a crazy fantasy about Tennessee Williams and Michel Foucault having an affair in Orillia, Ontario. It was made in response to the Orillia Opera House washroom bust where thirty-two men were arrested after extensive video surveillance. The performance and subsequent tape are structured around a debate between Williams’ outraged libertarian views versus Foucault’s analysis of a sophisticated state policing apparatus that purportedly collapses divisions between private and public space. Foucault asks his new Southern belle lover: why are we surprised by state suppression?

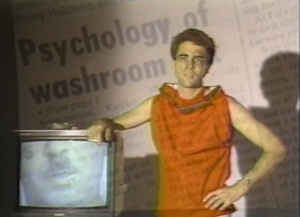

That work was a test-drive model for Urinal (100 minutes 1988) which was a more ambitious, feature length version. Urinal utilized more characters, six instead of two, but addressed this same question, again using the collision of discourses epitomized/embodied through “real” historical figures. Each of the six (all closet-cases with distinctly fluid sex lives) deliver a lecture on some aspect of the policing of public sex, presented in various documentary idioms. With a wink to the camera, Eisenstein does a Michael Moore-like, first person tour of the public washrooms. Frances Loring delivers a saucy social history of the washroom over two millennia in the manner of Barbara Ehrenreich. Yukio Mishima covers public and washroom sex in the arts and literature, quoting from poems, films and plays, including his own. Langston Hughes offers a documentary about men who have been busted, and gives us a melancholic tour of Southwestern Ontario in the manner of Michael Rubbo’s Sad Song of Yellow Skin. Florence Wild interviews activists like Svend Robinson who defended the men caught in the bathhouse raids — very Word is Out. Frida Kahlo wraps it all up with a Foucauldian analysis deconstructing state power. As the state increasingly encroaches on private lives — using systems of surveillance that include taxation procedures, bank cards, and surveillance cameras, and as we accept and consent to these new forms of domination — the only places men can find privacy is in public. If they can’t find privacy in their private lives, what remains is the anonymous space of the public washroom.

I wish he was still around; another two decades of Foucault would have been fabulous for all of us. The whole emergence of queer in the late 80s was very much an inflected Foucaldian project, refusing the increasingly smug categories of “gay,” and insisting that there’s something much more complex in terms of the contingent and fluid formations/practice of our sexualities. Sexuality never fits neatly between walls or in boxes. Categories were his passion — who produces them, who uses them, for what reason, and for whose benefit?

Mike: Urinal was made with little money but great ambition.

John: Mostly I had no idea of what I was doing. When you don’t have money, it’s always advisable not to know! It was half shot on film, half video. The film portion was done over five or six days using A Space as our studio. Adam Swica, a Funnel member, shot it, Midi Onodera pulled focus. Colin and George Hawken were the art directors, Leena Raudvee was production manager. The cast was local actors and activists including Paul Bettis and Keltie Creed.

Mike: Was that the first time you worked on that scale?

John: Up until then it had been small documentary/staged works with crews of one or two. Making a feature film was a stretch. The total budget was ten times what any of my previous tapes had cost — $35,000 — and came from the arts councils. It was a good experience. I was living in Beaver Hall, the artist’s co-op that summer, and brought in a flatbed to edit. David McIntosh was the picture editor, he held my hand through the entire post process. Glenn Schellenberg did the score. Piers Handling, who was programming Canadian features for the Festival of Festivals, came by and saw a rough cut he liked, so we had to finish. I suppose we did some sort of mix — the lab was PFA and were actually pretty decent to work with.

Mike: Colin Campbell said that your work wasn’t generously received in the gay community, but that it found a home on Queen Street.

John: It’s true. For the most part, Church Street disliked The Body Politic and the gay lib project it represented. The Body Politic, despite its obliviousness to the avant-garde, was very much part of Queen Street and the emerging art scene. The common cause was of course our shared opposition to censorship. This free speech umbrella allowed queers and artists, leftists and liberationists, punks and pansies to share some shade together. The crucial thing to understand was that Church Street was primarily a community of small businesses, whose values proceeded from that ethos, whereas the early Queen Street scene and the artist-run spaces was for the most part state-subsidized (leaving aside the trendy restaurants). That divide remains today, though of course as both scenes have grown ten-fold, it’s now much more complex and contradictory. There was a lot of generosity around my work in the Queen Street community, despite a suspicion or criticism of engaged, activist work in general. But there was an urgent undertow of, “This is important, let’s show this and talk about it.” Audience numbers were so small, all of us were going to everything. Because I went to other people’s screenings, they would come to mine.

Mike: Were you disappointed with the response in the gay community?

John: Absolutely. It took me awhile to figure it out, because I couldn’t understand why everyone in the world wasn’t excited by the avant-garde and rushing out to see Yvonne Rainer’s new feature. But for the queer community, even someone like Fassbinder was tough coin, he didn’t have much of a following. Now it’s important to note that there was always a gay intelligentsia and that tended to be defined in terms of the canon, academia, opera, dance, poetry, bookstores. Michael Lynch can stand as an emblematic example; a poet and friend who taught American Studies at the University of Toronto, a brilliant scholar and activist who nevertheless remained oblivious to a new generation of visual and media arts. He couldn’t or wouldn’t connect the dots.

At The Body Politic, Alex Wilson was constantly having to fight the collective for the paper to include reviews of performance and video art. When he put Colin Campbell on the cover with an accompanying article by my then-roommate Martha Fleming, the collective was deeply split. “This isn’t gay work. Colin Campbell is straight (this was years before our relationship, which was his first gay one), his drag is tacky and amateur, he’s making fun of women…” Another way of saying it would be that Colin was emphatically queer, but the Body Politic couldn’t understand his particular iteration of the Q word.

So while there was an on-the-ground relationship between Queen Street and The Body Politic, there was a vast range of differences within the collective to thinking through culture. I was a funny sort of figure because I was the only queer artist who was actually going to meetings and involved with political organizing. General Idea, David Buchan, and Colin were onside in terms of free speech, but their interests and identities didn’t extend to rallies and demos. I think they shared some distrust of a potentially dogmatic left politic, and that distrust was sometimes well earned.

Mike: Did you feel that the work you were making was playing to the converted?

John: Well, I knew it wasn’t, if the converted were defined as the queer activist community! They weren’t coming to video screenings at A Space. It wasn’t until gay film festivals started up in the late 1980s/early 90s that I saw queer audiences finally come together with art audiences. Church Street and Queen West could meet in the popcorn line called a gay film festival and sit side by side in the dark, playing footsies. I still think there’s a hugely crucial role that queer film festivals can play in our lives. In many ways, the fests are our campfires, the places we gather to sing songs and hear stories and stare into the flames together, warming our shins. (Many used to argue that the clubs and bars performed this role, but the bouncers and velvet ropes and VIP lounges that characterize the mindset, if not the actuality of such commercial spaces, ensures a pecking order is preserved, and all too often self-policed. By contrast, fests remain wonderfully, anachronistically democratic, places where wildly different ages and genders and races and bodies and incomes must all blithely snack on the same golden topping.)

I don’t buy the argument that the time of the gay fests has passed, eclipsed by the inexorable rise of gay wedding planners, steam-rollering normalization and the triumph of Netflix. I think the festivals have continued to reinvent themselves, and they’re still creating unique spaces for praxis and exchange for our diverse communities. Netflix may be convenient but it doesn’t warm our shins.

Mike: Can you talk about the first time you ever heard about AIDS?

John: I remember it vividly. I had just moved to New York in 1981 to live with my boyfriend Tony. We were painting his Front Street loft down in the fish market, blasting Laurie Anderson’s O Superman through the unbearable August swelter. The New York Times published a tiny, one-paragraph article about gay men on Fire Island. None of the lingo was in place, it was simply reported that men were getting sick and dying. Later that summer I got a job at AIVF, a national trade organization for independent film and video. Our cleaning guy was a cute leather queen that I got to know working late nights. Then in November he stopped coming and a few weeks later we were told he’d fallen ill and died. For me, he was the first one I knew personally. All through that fall everyone was talking about this new “gay cancer.” Was it poppers, SM practices, recreational drugs? It was clear from the start that this was going to be an epidemic of blame and finger pointing. The New York Native (gay newspaper, 1980-1997) was quite active in those early years trying to pursue different medical theories, from swine flu to CIA conspiracy theories. They epitomized a questioning spirit that refused to concede health concerns to the medical authorities — at the same time they became a platform for what would evolve into the HIV-denialist camp a decade later. I guess because Tony and I didn’t have a share on Fire Island we felt immune, like so many others. ACT UP (Aids Coalition to Unleash Power) and AIDS Action Now weren’t formed until 1987, six years later. Looking back, it’s interesting to remember that our activist responses took that long. Or rather, our first responses through the early eighties focused more on promoting safe sex and condemning Joe Public bigotry. It took a while for queers to mobilize against the glaring lack of government and medical community response. In the late eighties, I went to both ACT UP and AIDS Action Now meetings and demos, but I felt the best work I could do was in video. I began with Moscow Does Not Believe in Queers (1986), and then The ADS Epidemic (1987), The Pink Pimpernel (1989), The World is Sick (1989) and Zero Patience (1993). I was also part of several collective projects: I produced a Deep Dish TV compilation of AIDS clips called Angry Initiatives, Defiant Strategies. I co-curated a six-hour collection of AIDS tapes for Vtape and Video Data Bank, and co-produced a Rogers Cable TV series of half-hour tape with Michael Balser, Living With AIDS.

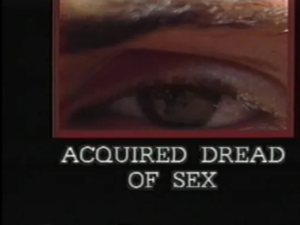

Mike: The ADS Epidemic (4 minutes, 1987) was a commission from the Public Access Collective for a project entitled The Lunatic of One Idea. Their website states that they “curate public art exhibitions that utilize urban screens as a means to …raise awareness in a city that is quickly privatizing every inch of shared space.”

John: They commissioned a number of artists to create short works for the Square One mall in Mississauga. The mall had a video grid of 36 monitors showcasing ads, and Public Access convinced them to insert artists’ work between the ads for a couple of months.

Mike: The ADS Epidemic transposes the “new” homophobia unleashed by AIDS onto a more generalized “fear of sex” in order to slyly reassert queer positivity. Colin Campbell plays the repressed Aschenbach, resplendent in false mustache and white suit. He is forced to look on while his young ferry passengers (including his real life son Neil!) are schooled in safe sex attractions. Stop motion flurries are scored by multiple grid views, echoing the work’s first commissioned destination, while hinting at the viral proliferation of pictures.

John: “The ADS Epidemic” was a dual purpose acronym, standing for Acquired Dread of Sex, and also pointing to the Gap and Pepsi ads it was sandwiched between. I wanted to use the idiom of advertising/consumerism to talk about how we are sold fear and homophobia. Glenn Schellenberg wrote the pop tune and I rhymed lyrics that faced off pro-sex queers against homophobic closet-cases. We re-created scenes from Visconti’s Death in Venice (1971) during a one-day, no-budget, period shoot (the budget was about twelve dollars), then braced for problems with the mall. But they were so upset with Vera Frenkel for doing a satirical piece about consumerism and credit cards that ours floated past their censorious noses.

Mike: Moscow Does Not Believe in Queers (27 minutes 1987) is a paradigmatic work of the 1980s, summarizing the ambitions of video’s second generation. After video’s mothers and fathers had poured out their real time reflections, what was left? Hybrid beauties like this and more. Moscow features a winning mix of conference memoir, dramatic interlude (featuring two post-coital hunks, one recently returned from a Moscow confab), Rock Hudson clips (mostly from Ice Station Zebra), and voice-over reflections. Relentlessly witty, it gathers up historical factoids in its sexy, multi-screen address, and maps out late-eighties Moscow cruising areas, bars, sauna and beaches.

John: The bookends of the work were based on real experience. In the airport when we were leaving, every newspaper headlined Rock Hudson’s AIDS disclosure. When we came back from Moscow two weeks later, his disease had progressed, and there were fears that when he appeared as a guest star on Dynasty, he might have infected his dear friend Linda Evans. I was attending a conference of 30,000 Youth for World Peace and Disarmament (one of 300 delegates in the Canadian contingent), shipped off to Moscow for a stately propaganda exercise. Gorbachev addressed our opening ceremony which featured the spectacle of 2000 Soviet youth manipulating coloured cards to create a human pixel board. It’s a performance technology of jaw-dropping precision and spectacle that’s now lost to the world in this digital age — and it’s still heartbreaking to think what someone like Lepage or Jarman or Greenaway could have done if they’d been allowed access to all those kids and cards, even for a night!

I used scenes from Rock’s cold war epic Ice Station Zebra (1968) to show him piloting a submarine up the Moskva River to infiltrate the youth festival. His closeted sexuality became a counterpoint for talking about the lives of several closeted Soviet queers. I met an interesting cross-section of writers, translators and party boys. Much more a parody of the perennially popular ethno-diary-documentary form than a sustained investigation of queer Soviet realities, my real topic was the cultural cold-war (equal parts projection, nostalgia, exoticism, overcompensation, incomprehension) that overwrote all expressions of sexual identity, east and west.

Mike: Can you talk about Alex Wilson?

John: I met Alex in 1979 through The Body Politic, where he edited a few articles I wrote, and then in 1980 he appeared as St. Sebastian in one of my early videos. He was one of my first friends to be diagnosed HIV positive, and when he became sicker in the early nineties, Colin (Campbell) and I coordinated the care team — both he and his partner Stephen Andrews, who was also positive, really needed the help, despite the emergence of community support services like Casey House.

I was on Michael Lynch’s care team as well, which was hugely organized with spread sheets and charts and lists. For Alex, we were more intuitive, simply trying to ensure that Stephen had time off, and that the main caregivers didn’t burn out. Once a week each care team member would make dinner and watch a movie with Alex or read poetry. Sometimes Alex would sleep through our shifts completely.

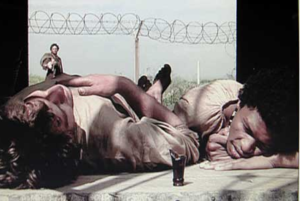

Near the end, Stephen and I took Alex to a friend’s cottage, because it was just so hot in their house. The idea was the pleasure of being able to lounge lakeside. It’s one thing when you’re caring for someone and very in touch with their physical limits, even when their body is swathed in clothes. But when Alex was undressed in nature, negotiating rocks and sunken logs and water, there was an added confrontation with how far his body had degenerated. Going swimming with him is a very vivid memory. I’m a pretty good swimmer, so I was trying to find a way to lifeguard his movements in the water, but we couldn’t manage. We was so weakly unable and so unhappy because of this. Sadness marked the whole trip.

This was at a time when there was no treatment, except for AZT, which was making everyone we knew sicker. I can’t remember what treatments Alex was taking during that time, but Stephen took nothing until protease inhibitors were released in 1996. He made a series of conscious choices not to get tested or undergo treatments, during that pre-protease period when medical science offered so little. So many friends, both in the art scene and the gay community, were getting sicker and dying in that period: activists Ross Laycock, Michael Lynch and Michael Smith, Jorge and Felix of General Idea, visual artists David Buchan and Rob Black, George Smith (another activist who had been in a few videos of mine), Ray Navarro and Vito Russo in New York.

In the fall of 1992 I shot Zero Patience. I spent the winter and spring editing and finishing the film, while running around and taking care of people like Alex and Michael, and then going home to be with my mother. My mother had been living with cancer for many years, it had gone into remission and then recurred. She died in July. Alex died three months later.

Mike: There were bad deaths.

John: There were bad deaths, sad deaths, angry deaths, graceful deaths. Michael Smith chose suicide, he wanted to leave on his own terms, surrounded by friends. Going to see him in the hours after his death, framed by candles, by his community of queer punks and activists… I can remember every minute.

Our care team decided to take Stephen out dancing every week, Alex would join us in the early days when he was feeling better. Years before the Richmond Street club district became unbearable we would head to Go-Gos for Men at Richmond and Duncan (just across from the old Fuse/Art Metropole offices where I’d got my first art job) drink too many Cape Cods and sniff coke lines — maximum fun. Dancing for six hour stretches was a good survival instinct. Memo to self: we should probably reinstate the tradition in these grim times, but we don’t.

Mike: Zero Patience (95 minutes 2003) must have been a response to these devastations.

John: Exactly. It came out of the activism of that era, it was very much “ACT UP: the musical.” Like The ADS Epidemic, I wanted to use pop culture to speak to queers who might be turned off by ACT UP militance and politics. Humour, irony, camp, and musical numbers tried to capture this moment of extreme stigmatization. This epidemic of blame.

Randy Shilts’s book And the Band Played On (1987), despite much well-documented outrage against the Reagan administration’s indifference to AIDS, still trafficked in an egregious primal scene calculated to make the book a best seller. Its overarching narrative claimed an oversexed Air Canada flight attendant had brought AIDS to North America. This was the sexy story people wanted to hear. When the epidemiology was examined, this theory was exposed as a crock — all you could really say about the flight attendant Gaëtan Dugas was that he’d demonstrated that the infection could be sexually transmitted. In fact, as my film argued, he could be considered a hero of the epidemic for helping the epidemiologists with their work, not a monster.

Glenn Schellenberg, the composer, was central to Zero from the start. He was involved in ACT UP and he’s HIV-positive himself, so the project was very personal to him. He composed the music and I wrote lyrics. We were both fascinated by pop’s power to get inside people’s ears and hold them in the room even if they didn’t share the radicalism or the message.

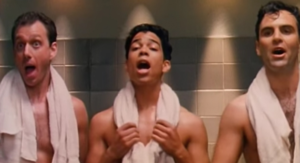

Mike: Can you talk about the swimming pool scene?

John: It all comes back to swimming, doesn’t it? Sir Richard Burton is searching out the crowning piece for his Hall of Contagion and tracks down the ghost of Gaëtan, the AIDS originary myth he names Patient Zero. When he tries to get Zero’s doctors and friends to denounce him, they offer only appreciations, but he manipulates the footage to make it seem like Zero was a monster. But Berton and Zero end up in bed together and then Zero looks into a microscope that shows one of his old blood samples (stolen by Burton from his doctor). What he sees is a bloodstream swimming pool starring Ms. HIV played by Michael Callen, queer acapella singer and AIDS activist extraordinaire. It was Michael’s idea to dress up Miss HIV as Barbara Streisand with the exact wig from On a Clear Day You Can See Forever (1970), and the exact black dress from Funny Lady (1975). Most of all he wanted to hold a note onscreen longer than Barbara ever managed. Glenn rewrote Scheherazade with the requested “big finish.” Michael arrived from San Fran in the morning, recorded the song in the afternoon, and spent the next day on set in costume, flirting with all the grips and camping up a storm. What audiences have no way of realizing is that he did all this with half a lung. Two weeks earlier he had come down with another bout of pneumocystis pneumonia. He was on tour with his band The Flirtations, and they had to cancel a bunch of gigs because he was back in hospital. His lungs were giving out, it was just heartbreaking. I said to him, “Michael, you’re a friend, the film doesn’t matter. We’ll do it in three months when you’re better.” And he said, “No, there may not be three months.” So when he came to town he was really ill, but he nevertheless acted and sang amazingly with only half a lung, and held his note longer than Barbara, and was the diva of our dreams. He died three months later. We dedicated the first screening to him.

Staging the bloodstream was a way to let the blood talk back. The scene offers a small flirtation with alternative theories of HIV transmission featuring the feminist performance group The Clichettes as various viruses. Michael himself was very invested in alternative theories, though I think if he’d lived he would have repudiated the denialists who came later (Mbeki et al.) who were so notorious for saying it’s untreated tertiary syphilis, it’s vitamin deficiency, or malnutrition — especially in the South African context where those denials cost so many lives. Michael was someone who vigorously questioned accepted wisdom about what HIV is, and while the two of us didn’t agree about everything, he represented an important spirit of inquiry. This scene opened the door to some of those debates.

Our definitions of sexuality have become immensely more complicated as a result of AIDS. The 70s-era, gay lib movement established a North American-style narrative of triumphalism — from closeted and repressed to a self-determined individual who enters into a defined community of like-minded people sharing a sexual identity and a value system, one that could lead to social integration (the bars, the baths, the ghetto) and perhaps activism. AIDS complicated that narrative by reminding us that the walls between sexualities are of course non-existent, practices are always more porous and contingent. In the plain speak of the plague: the way many people actually fuck is rarely “strictly gay” versus “strictly straight.” The construction of a smug, monolithic gay community crumbled before our eyes when we saw seroconversion occur across a spectrum of identities, genders, lives, practices.

Mike: Because married men might vacation in the bathhouse…

John: Exactly. We all knew this, but there was an attempt in the 70s to construct an idealized community based on self-realization and coming-out. And the ideal community blew up in our face because AIDS didn’t recognize any of that. If AIDS was out to kill promiscuous gays as the preachers claimed, and destroy an organized, out gay community on Fire Island, then it did a very bad job, because it immediately spread further than any such labels or categories. However, despite such insistent reminders that sexuality is a porous, slippery beast, to this day there’s a narrowness evidenced in the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” debates around the American military, or the questions of gay marriage and gay families. There’s still so many attempts, both by the mainstream and the gay community itself, to contain and consolidate diverse sexualities into discreet boxes. Even the polymorphous radicalism of “trans” sometimes gets streamlined into claims of a unitary identity.

Mike: By adopting the more popular form of a feature film, did you hope your message would reach a wider public?

John: Yes, and it did. I made Urinal as a feature film because video art distribution at the time was still relegated to a handful of galleries and classrooms. Making a feature-length movie immediately opened doors to new festivals and audiences. Zero Patience had theatrical releases in thirteen countries, more than video art could ever deliver. It opened in the United States on the same weekend as Philadelphia (1993), which was the best thing that could have happened because critics were offered two radically different versions of the epidemic. Zero was pretty widely seen, even if it had a tough time with many critics and audiences.

After I made Urinal and went to The Canadian Film Centre I consciously climbed onto The Ladder, as I like to call it. It was a moment when filmmakers associated with the queer avant-garde were making extraordinary works that garnered some mainstream attention. B. Ruby Rich coined the phrase “New Queer Cinema,” attempting to address the new turn in American indie cinema represented by Gus Van Sant, Todd Haynes, Tom Kalin, Christine Vachon, Gregg Araki et al. Queer cinema was top of the pops, and everything pointed to a new renaissance that never actually came to pass. In the decade that followed we predictably got a rush of frothy gay American comedies featuring cute, fab-ab beach boys.

Mike: Can you take me back to The Making of Monsters (35 minutes 1991)? It was made at The Film Centre, a finishing school for industry players kick-started by Norman Jewison.

John: I was accepted as a writer-director in 1991, and wrote what I thought was an utterly brilliant script about Trudeau’s sex life and circumcision. They got upset and refused production, swearing all the while that it had nothing to do with the huge amounts of money they received from the Liberal government. I had a choice. I could throw a hissy fit or stay on for the opportunity to make a well-crewed film for free. So, swallowing my outrage (and filing away my Uncut script for a rainy day), I quickly wrote another script.

I’d been rereading the Brecht-Lukacs debates about the efficacy of realism while being indoctrinated in the gospel according to Norman Jewison-style humanist realism. It’s certainly not true that the Film Centre waves only the flag of realism, they do represent and teach a much broader curriculum. But realism is at the top of their (and society’s) pyramid. It’s the fundamental building block of so-called serious cinema, and if you want to climb the Canadian film industry ladder, and that was our job description, you better get real about it.

I’d been the MC of Gay Pride in 1985, the year that grade-school teacher Kenneth Zeller was kicked to death in High Park by five teenage high school students on the last day of school — a horrendous gay bashing the city still remembers well. The Clichettes had just finished performing when I was handed a note onstage. Faith Nolan was about to come up, and there I was in my No More Shit dress, breaking the news of this horrible murder to a crowd trying to celebrate our various queer victories of that year.

This haunting case has always stayed with me. I got copies of the court transcripts where defense witnesses argued that the killers were good boys because they played hockey. Participation in our national sport apparently guaranteed their good citizen credentials. In contrast, Ken had been a figure skater, he was feminine to their masculine, a teacher while they were students. All these dichotomies, mirrors and echoes played out within the context of the trial.

The title of The Making of Monsters speaks to the ambition of the film. Once again taking a page from Foucault, it’s trying to analyze the institutions that make or produce monsters. Where does a collective culture of hate come from? If this stuff is learned, as opposed to bred in the born, where do we learn it from? While I had my fun with hockey in the film — making jockstrapped hunks in hockey masks dance Hockey Night in Canada choreography — the movie doesn’t argue that hockey culture produces hate per se, but rather that it’s a symptom. The schools are really what I end up focusing on, in part because the killers were school boys.

The trial transcripts and reporting were echoed in my script, and this was instructive because the facts and details of the case allowed the script to more or less write itself. I’ve worked on three movies based on court cases: Monsters, Proteus (2003), and Rex vs. Singh (2009). In each instance there’s both an instinct and a mandate not to invent, not to depart from the facts as they’re recorded — most often because the facts are almost always idiosyncratic, peculiar, unique, poetic. (In contrast, most made-for-TV versions of real-life cases tend to stray from the idiosyncratic specifics, and in the process of generalizing, reduce and erase both the fascination and the pathos of the story they’re purporting to tell.)

An obvious point about these court transcripts — their “facts” are as much constructions as any fiction — again, Foucault reminds us that these accounts are first and foremost discourses, exercises in how a state expresses itself through its citizens, warts and contradictions and all. Whether these “facts” are true or not is an irrelevant question, it’s the instrumentality of these records that’s more of interest — what they trigger, what they suggest in terms of starting to tell a story about the subject at hand. Hewing to the facts should be understood as a sort of automatic writing. Or so says the talking catfish.

Mike: Why a musical?

John: The idea came from John Gay who wrote A Beggar’s Opera in 1728. He was working within a popular idiom of the time, the ballad opera. Popular songs of the day were inserted into a play with rewritten lyrics. He would take a song like Our London Is a Gay Town and turn it into Polly is a Sad Slut. The shock of those new lyrics would electrify the audience, because they knew the melody and tapped their toes, but the words were new. This is more or less the strategy that Brecht and Weill used in The Threepenny Opera which uses Gay’s story and characters to critique twentieth century capitalism, and familiar idioms from Weimar music hall tunes to sweeten the ride. We, in turn, boosted their songs and added new lyrics — call it a continuum of appropriation. Surabaya Johnny became a duet about monogamy and promiscuity; Mac the Knife became a Queer Nation anthem.

This got us into some trouble with the Kurt Weill estate who initially released festival rights to us for excerpts from five songs (music only). When England’s Channel 4 rang with an offer we returned to the estate who asked for $40,000, not coincidentally the amount of the sale. The Film Centre was ready to pay because there was a lot of excitement about the film; it had won prizes at TIFF and Berlin. But when the Weill estate saw the film they freaked and declared they would never ever sell us the rights. That same year they licensed Mac the Knife to McDonalds to sell hamburgers; I guess their new lyric ‘It’s Mac tonight’ was less eyebrow-raising than my “I Hate Straights.”

As a result, despite the fact that the Weill songs in Canada have been in public domain since 2001, and despite the fact that the film is a textbook case of fair use in the States, the Film Centre refuses to allow the film to be shown anywhere, essentially because they’ve been bullied by Warner-Chappell who represents the Weill estate. I spent this past year lobbying the CFC to allow the film to be shown as part of my TIFF Lightbox/AGO retrospective, and they refused, to their ever-lasting shame.

Mike: Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) was a friend of Brecht, and an important touchstone for you to negotiate some of these copyright thickets.

John: Mr. B and his famous thought bubble, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” unfurled a critical flag about the death of the original and the ascent of the copy that is flapping even more vigorously over today’s digital landscape. Mr. B was an ardent, if unconventional Marxist, and his musings were directed at an imagined workers audience, inventing their subjective participation in the new world cultural order. Among his many squibs, he was one of the first socialists to see the democratizing potential of new technologies (photography, film, offset printing), tools which could be used to emancipate workers and democratize artistic production. He argued that when art loses its aura of originality, it becomes reproducible, democratized, readable; a vehicle for meaning that can be interrogated and contested.

For artists, Mr. B was a prophet of an emancipatory postmodernism. When the copy is as valued as the original, then the very idea of originality and the precious art object becomes gauche. Implicitly, this extends beyond the art object to encompass the very nature of creation. Consider playwright/actor Linda Griffiths, speaking of creativity in my 1997 video Uncut: “I’m a thief. All artists are thieves. You’re constantly taking bits and pieces of things from everywhere, snatches of conversation, your friends, your lovers, they’re all going to end up in the work. The only way that I can feel right about doing what I do is to make sure that I give back tenfold. So I steal, and I give back tenfold… It better be good if you’re taking a real person. It better be really funny, or cruel in exactly the right way. I think there’s an inner responsibility to that person.”

Linda speaks two truths: that all artists steal, and that such stealing carries with it a set of ethics. “It better be good.” A.A. Bronson, member of the artist collective General Idea, also interviewed in Uncut, likewise assumes that creating is stealing. “When nineteenth century romantic painters painted a landscape or a person, that wasn’t considered somehow infringing upon the copyright of the landscape or the person. In the same sense now, the world of media and images is our natural environment, it is out nature. The whole concept of copyright is totally nonsensical.”

Uncut (92 minutes 1997) began in 1990 as a short film convergence about Pierre Trudeau and circumcision — it only became an eccentric treatise on copyright after my run-in with the Weill estate. I was a member of Queer Nation at the time, when the outing debates were at their height. I wanted to talk about the nature of gossip, about the fascination we share for the private lives of public figures, and what it means when we claim categorically that someone is gay or straight. Having been involved in a previous decade of lefty gay activism, where the social construction of sexuality was considered axiomatic, and any fixed definition of desire was deemed suspect, it seemed particularly regressive in 1990 to speak of sexuality in such binary and reductive terms.

I volunteered Trudeau as a useful test case. Despite his very photogenic decades of hetero dating and mating (including Maggie, Barbra, Margot, Liona, Brigitte, ad infinitum), rumours had persisted since the beginning of his public career about his secret queer life. I included some of my favourite bits of gossip in the script: the secret attic for callboys at Sussex Drive, the long-standing affair with Fidel Castro. In the course of my research, I met dozens of men who claimed they’d slept with men who’d slept with men who’d slept with Pierre. The more I heard, the more I was awed by the depth and breadth of a collective fantasy about PET that still seems to grip our gay demi-monde. Why isn’t it enough for us to merely lust after Pierre, after Tom Cruise, George Clooney, Richard Gere? Why must we obsessively invent their secret gay lives, despite their often overwhelming heterosexual credentials? Is George Clooney more aphrodisiacal because he denies it, while George Michael is less successful fodder for our fantasy mills because he’s finally confirmed that he plays for our team?

Uncut wasn’t concerned with any “truth” about Pierre, though I did give a character the argument that if Trudeau was gay, surely someone by now would have come forward with the photos. Instead, I was more interested in what it means to fall in love with a mass media icon, what it means to project desire onto a photographic fantasy. Indeed, in the editing, I spent an intimate week selecting the archival footage of Pierre, and for the first time in my life found myself succumbing to his considerable black and white charms. The crush didn’t last longer than the off-line, but it was instructive, becoming smitten by the aura of his pock-marked originality.

Gay/Straight. Cut/Uncut. I wanted these two binary oppositions to play off each other through the course of the film, posing implicit questions for one another. Society shouldn’t care if you’re gay, or uncut, or straight, or cut: who you sleep with, or what’s covering your dick are things which shouldn’t signify. But they do, Mary, they really do. Society does care, passionately, irrationally, and with a fervour that demonstrates the high stakes involved. The meanings of sexuality, and of circumcision, aren’t objective — they mean nothing outside of history’s and culture’s constructions. It is precisely within history and culture that such meanings acquire power, and in the process, become fascinating. So while my first Peter (the typist) is obsessed with whether Trudeau is gay, my second Peter (the grad student) is fixated on whether my first Peter is uncut.

Mike: How would you feel if someone ripped pictures from your movies?

John: It breaks my heart that it’s never happened! I can only echo Linda’s words: make it good and make it your own. I think stealing is fundamental to every act of art making. How do you learn to play an instrument or look through a camera? We carry inherited histories of looking. Everything we do is mimicry, an echo or quotation of what’s come before. Auteur theory and originality myths are taken apart by the way we use digital media everyday. File sharing and downloading make the death of the author a lived reality.

Mike: The desktop as model for the self. Separate audio and video outputs, skye calls, email — it’s like wearing all the masks in the Halloween store at the same time.

John: It’s the opposite of, “Oh what’s the point, it’s all been done before.” But of course it hasn’t been done exactly the way you’re going to do it tomorrow. What you did yesterday, and even the person who did it, is different than what will follow later. Maybe we could learn more from evolution, that art evolves somewhat like bullfinches and iguanas, though the selection may be more unnatural than natural, and survival may be more fetish than fittest.

Mike: Lilies (95 minutes 1996) is one of your smash hits, a tender play within a story within a film. The church setting is derived from the adaptation, yet it feels very personal somehow, the whispers of the confessional, even the prison feels like these are surrogate homes for you. How did you chance across this story, and what made you think it could be made into a movie on such a scale? What did it mean to win all those I dream of Genies, even (gasp) best picture?

John: Lilies is always best understood as a film of Michel-Marc’s wonderful play. My job description was always to get inside his uber-theatrical story and make it cinematic, while staying true to his explicitly theatrical themes. For me, it was a delight to take off the burden of authorship (the story, the writing) and concentrate 100% on the craft of directing. In the process there was the opportunity for much grateful quotation: Jarman of course, Fellini, Lepage (I hope!)

Co-producer Anna Stratton owned the rights to Lilies, and we were working together on Zero Patience. She introduced Michel-Marc and I, and we really hit it off. For him, it would be his first play adapted to the screen — for myself, the first time I would be directing someone else’s words. So the adventure was equal in both directions. He was very open to my visual ideas for the adaptation, and in turn, he was invited to all our rehearsals and days on set.

Despite the many pleasures of working with Michel-Marc, working on that scale, with that many cooks in the kitchen (producers, distributors, funders), was difficult for me. It was the first (and last) film where I wasn’t a co-producer, and the experience helped clarify for me my own priorities, especially in terms of scale, form and authorship. I went on to write/direct/produce Uncut six months later, on a budget 1/20th the size of Lilies, and despite its own headaches and hiccoughs, that experience helped confirm for me where my heart lay — firmly on the video art side of the video/feature film divide.

Mike: Tell me about Law of Enclosures (111 minutes 1999).

John: It’s hard to reconstruct what my thinking was. I really loved the Dale Peck novel, an experimental memoir based on the queer writer’s parents. Henry and Beatrice are a married couple, and the book offers a duet between the first and final years of their 50-year relationship. The movie follows suit, but they’re stuck because the Gulf War is playing endlessly on TV in both time frames. The project offered money and stars, but was misguided, and (again) made me realize that I couldn’t swallow realism. I guess it was a hard lesson to learn because I really like realism when other people do it, like the Dardennes. They believe in it, passionately, and thus, in turn, I can believe and accept their methods and stories, investing deeply in it, just as we’re all supposed to do. But with Law of Enclosures, there was a gut realization; I couldn’t (or shouldn’t) do it for myself. Though it took another feature (Proteus) before that lesson was fully apprehended. (I’ve always been a slow learner!)

The minute I finish a film I immediately realize how I should have made it. It’s happened with everything I’ve ever made (both features and docs and shorts) except for Fig Trees (2009). Against all odds, I’m still happy with that film. I think that’s a good sign, and it made me feel that this is a type of hybrid practice that can continue working for me. So I’ve stopped trying to make even inflected, magical, compromised or fragmented realisms (basically, all the previous features except Urinal and Uncut). Fig Trees has been very enfranchising. I’m now working on two more opera documentaries, which are going to keep me busy for a while.

Mike: Proteus (97 minutes 2003) is a history lesson disguised as a love story.

John: Six years ago, South African video artist/activist Jack Lewis dug up a 1735 court transcript in the Capetown archives: the true story of two prisoners, one Dutch, the other Khoisan, who were executed for sodomy. He wanted to make a film of it. And he wanted to collaborate. We’d been friends for a few years, but this was a unique pitch: co-writing and co-directing a feature-length, low-budget sodomy epic, shot on location on Robben Island in English, Nama and Afrikaans. How could I refuse?

He had the transcript translated and sent it along. On first reading, I was underwhelmed. It told of Claas Blank, a Khoisan native (Hottentot in the parlance of the time), and Rijkhaart Jacobsz, a Dutch sailor, both of whom were serving time on Robben Island. They’d been caught in a hut performing the unspeakable crimen nefandum (or mute sin) of sodomy. They were brought to trial at Cape Castle; witnesses duly established their guilt beyond doubt. Their confessions were introduced and the verdict was declared: death by drowning in Table Bay. Execution costs were invoiced to their families.

Nothing about this judgment was surprising or shocking: sodomy was then considered worse than murder, the death penalty was de rigeur, and the Dutch courts prided themselves on their scrupulous and transparent administration of justice. Interesting, certainly, in terms of the case’s interracial aspect, given that the Khoisan peoples in that era were classified by the Dutch as subhuman, making social (and especially sexual) interaction between the two unthinkable. Interesting, also, in that the courts made a point of noting that the two were the same age and that the crime was “mutually perpetrated,” a departure from the more common practice of an older (richer) man fucking a younger (poorer) one. Finally, however, just another 18th century sodomy trial calling out for naturalistic Merchant-Ivoryish treatment. Someone should make the film, certainly, (Rupert Everett as Rijkaart?), but it didn’t feel like my turf.

Jack emailed back: look deeper, between the lines, particularly on page seven. One of the witnesses, the prisoner Augustijn Mulhasz, testified that in 1725, he had seen the two fornicating while on a prison detail collecting train oil (seal blubber), and that he had complained to the Island Sergeant, but the Sergeant did nothing. Which seemingly meant two things: that Claas and Rijkhaart had done the sodomitic tango at least twice in a decade, which made us think there were probably more times during those ten years, making them — what — lovers? Partners? Fuck buddies? What words might these two illiterate convicts have had for these acts and for one another (affective, social, formal, slang), speaking to each other in their common middle Dutch (a creole in the process of becoming Afrikaans), speaking about each other and themselves a full 150 years before Foucault identified the emergence of the self-conscious homosexual European subject? What words would these men have used to describe those ten years, that string of acts? Secondly, the authorities had known about them via the Mulhasz complaint and done nothing. What changed in 1735 that resulted in their trial and execution?

We committed ourselves to building a script out of every fact we could glean, staying as true as possible to the world of these sodomites. At the same time, we had no pretensions about the “truth” of our account. We knew the version of the tale that resulted would ultimately be Jack and John’s, not Claas and Rijkhaart’s. The struggle was to find some mechanism to foreground this, some technique to keep our film from resembling a seamless tapestry.

The Robben Island that everyone knows is the 1964 jail, where Nelson Mandela and fellow ANC militants were sentenced to life imprisonment. Indeed, the Island is now South Africa’s top tourist destination, a museum operated by former prisoners. We were committed to shooting on the Island itself, and the Island authorities, all stalwart ANC members, granted us permission despite some controversy.

The first thing we did was catch the boat to the Island. Bleak, windswept, and barren, pounded by waves and punishing currents, it boasted an almost perfect track record: only one prisoner had successfully escaped during those three hundred years. We wandered the Island, searching for the ghosts of Claas and Rijkhaart. The slate quarry where they’d broken rock was overgrown and abandoned, but with a bit of set dressing it would still be stunning as a location — except for the reverse angle, which looked across the water at the emphatically twentieth-century city of Capetown, nestled in the shadow of Table Mountain. (Indeed, ANC prisoner Tokyo Sexwale once commented in an interview with Jack about how they maintained hope during the long apartheid struggle: “The only mistake they made when they imprisoned us here was giving us a view through the prison bars of Table Mountain.”)

And that’s when the ball bounced, or rather, the penny dropped. The pristine past of 1735 that we sought to recreate didn’t exist, couldn’t exist — it would always be haunted by the present, by every image we know from our century, by Biko and Verwoerd, by Mandela and Botha, by whites-only beaches and blacks-only townships, by passbooks and colour classifications and funeral marches and now, by ten years of democracy when South Africa became the first country in the world to enshrine gay rights in their constitution. No matter where we looked, there would always be concrete chunks of the brutal past and the difficult but hopeful present, interrupting the view.

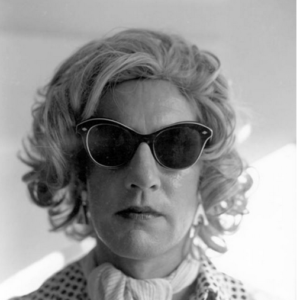

So we embraced and extended these unavoidable modern-day anachronisms (concrete and otherwise) to include the curbs and telephone poles and light switches that littered the landscape of our story, focusing on those that particularly invoked 1964, the year of Mandela’s incarceration. We shot the trial of Rijkhaart and Claas in the actual Cape Castle where they were convicted, but added a Greek chorus of 60’s stenographers, complete with cat-eye glasses and beehives. We made the convicts fetch water from a concrete water tower surrounded by barbed wire, collect shells for the lime kiln in green plastic bags, and smoke dagga (dope) using a broken coke bottle. Our Governor’s wife presides over a drawing room done up in proper Dutch décor, but a baby-blue portable radio sits on her dining room table. The botanist Niven who runs the prison garden sketches with a bright yellow HB pencil. A German Shepherd guard dog keeps the prisoners in line, and two Dutch settlers chase Claas in a jeep. Indeed, some audiences have seemed unwilling to credit our anachronisms as intentional. At a screening in the Hamptons, one audience member indignantly informed us that jeeps weren’t invented until the 20th century.

For Jack and I, this way of picturing history made more sense to us because history is always an exercise in looking back through glasses clouded with the dirt of our present moment. It’s impossible to know what Claas and Rijkhaart really experienced, felt and dreamed, because we weren’t there. We could only invent our version of their story, a version that’s specific to our imaginations, and our lives today. Because we weren’t pretending to be “pure,” the beehives and concrete breakwaters allowed us to be “true” to our 1735 story, and most important, true to the memory of these two forgotten convicts.

Mike: When did you become engaged with the question of Palestine?

John: In 2003 Gita Hashemi curated “Negotiations: From a Piece of Land to a Land of Peace,” a ten-day event that included screenings, talks and performances at A Space. This was during the second Intifada, and various sectors of Palestinian Civil Society put out calls for solidarity. One of the off-shoots was a small collective named The Olive Project with four members: BH Yael, Richard Fung, Rebecca Garrett, and myself. The concept was for artists to make two minute videos that would appear online and utilize some element of the olive — metaphorically or literally — to speak to Palestine’s occupation.

The Olive Project was part of a larger group named Creative Response, inspired by Gita’s project — and within that, I was a member of the media committee (what we liked to call the T-shirt committee). I designed a series of T-shirts that were typographic: Bold People Against the Occupation, in bold lettering. Frilly People Against the Occupation, in frilly typography. My fave was Dingbats Against the Occupation. It had to be subtitled because you can’t read dingbats.

In 2006 I signed the John Berger call for an academic and cultural boycott of Israel. It asked signers not to “visit, exhibit or perform in Israel,” citing worsening conditions in Lebanon, the West Bank and Gaza. Deaths occurred nearly every day, often of children, land was being stolen, malnutrition was rampant. The closing lines of the Palestinian call offered a five point checklist of solidarity.

“We, Palestinian academics and intellectuals, call upon our colleagues in the international community to comprehensively and consistently boycott all Israeli academic and cultural institutions as a contribution to the struggle to end Israel’s occupation, colonization and system of apartheid, by applying the following:

- Refrain from participation in any form of academic and cultural cooperation, collaboration or joint projects with Israeli institutions.

- Advocate a comprehensive boycott of Israeli institutions at the national and international levels, including suspension of all forms of funding and subsidies to these institutions.

- Promote divestment and disinvestment from Israel by international academic institutions.

- Work toward the condemnation of Israeli policies by pressing for resolutions to be adopted by academic, professional and cultural associations and organizations.

- Support Palestinian academic and cultural institutions directly without requiring them to partner with Israeli counterparts as an explicit or implicit condition for such support.

In 2009 I was asked by a San Francisco queer activist group to pull Fig Trees from the Tel Aviv Gay Film Festival, and this request set off a chain of questioning. It was only a few months after the Gaza massacre.

Mike: On December 27, 2008, Israel began its devastating 22-day assault on the Gaza Strip. Dubbed “Operation Cast Lead,” 1,400 Palestinians and 13 Israelis were killed. Widely misreported in the press as a “war,” instead of a civilian slaughter that targeted schools and hospitals, it was initiated, according to the website of the Israeli Defence Ministry, on the day of the US elections as a deliberate ceasefire violation by the Israelis who sent soldiers into Gaza to kill suspected “terrorists.” The predictable Palestinian rocket response provided the necessary cover for an attack that had been drawn up more than half a year earlier.

John: The Tel Aviv festival claimed it didn’t receive funding from the national state but only the city (a claim which later proved to be ingenuous at best). The fest is grassroots and queer, run on a shoe-string by filmmakers — not an obvious target of boycott. However, the San Francisco activists convincingly argued that it functions as an agent of pinkwashing — providing a gay Band-Aid to mask the sins of occupation. So, with much regret, I withdrew Fig Trees, and this decision, which I thought would sink without a trace, instead blew up in my face. People sent extremely nasty letters and various film festivals were upset. My dear friend Wieland Speck — who programs the Panorama section in Berlin, and who has been a real champion of the Tel Aviv Festival — made a personal appeal. He felt boycott was going backwards, we should all be talking together, working from within, trying to change things. This is the most common response: that boycott prevents dialogue. The more dialogue there is, the more conditions will change on the ground.

Palestinian Civil Society argues back that dialogue has been exhausted — we’ve been trying to engage in dialogue ever since 1948 (the origin of the Israeli state), and things have only gotten worse. Sometimes these dialogue efforts are band-aids that hide the ongoing wounds of settlement and occupation. If dialogue becomes normalization, promoting the idea of Israel as a modern, liberal, groovy democracy, a sandbox of debate and ideas and freedom of speech, then this only does the state’s bidding. With someone like current Prime Minister Netanyahu at the wheel, it’s clear his goal is nothing less than reclaiming the entire territory for greater Israel, and obliterating the West Bank and Gaza. Whatever Netanyahu’s day-to-day tactics might be, the long term dream remains the same.

Mike: In the summer of 2009 you made a very public withdrawal of your short film Covered (15 minutes 2009) from the Toronto International Film Festival with an open letter.

27 August 2009

Piers Handling, Cameron Bailey, Noah Cowan

Toronto International Film Festival

Dear Piers, Cameron, Noah:

I’ve come to a very difficult decision — I’m withdrawing my film Covered from TIFF, in protest against your inaugural City-to-City Spotlight on Tel Aviv.