Zero is a Lens: an interview with Stephen Andrews (2005-12)

How is it possible that anyone can talk like this? That’s what I keep thinking as Stephen rolls out the bon mots, as if he’s a living novel. I was in the midst of working on a movie about AIDS, certain that the visuals were carrying the whole story until a couple of friends assured me it was perfectly meaningless without the prison house of language. I sought Stephen out for a conversation about our experiences, and we found ourselves laughing through those plague years, the graveyards and catastrophes. Half a dozen years later, after he had made yet another movie (was he becoming a filmmaker?) I interviewed him again, asking him to run through his slim but handsome filmography.

Mike: I’ve just discovered pine beetles in my apartment.

Stephen: How do you know they’re pine beetles?

Mike: The building’s kind and all-knowing maintenance supervisor came by and announced, “Pine beetles.” “Should I be worried about that?” “No, you’ll just clean everything here, and it will be fine.” As a result, I threw out 20 years of HIV-medication bottles.

Stephen: How come you’re saving them, are you a hoarder?

Mike: I thought one day I would do something with them. And one day never came.

Stephen: What number of cocktail are you on? How many have you used?

Mike: I think I’m on number four.

Stephen: I’m on four or five.

Mike: That’s not many.

Stephen: Over a ten year period?

Mike: Ten years?

Stephen: No wait, it’s been sixteen years. The drugs came online in 1996, right? September 1996. I know because I was just about toast. CMV (cytomegalovirus) had started and I weighed almost nothing. I was a total disaster area. I jammed my foot in that door as it was closing. I started the drugs when I got back from kayaking with John and went on medication the next day. They didn’t work for the first month, I felt just vile, and then on the thirtieth day the light started shining again. (laughs) I was riding in a car and felt strangely happy, which I hadn’t felt in quite some time. I thought, “Oh I don’t feel like projectile vomiting.” It’s amazing what that does for your sense of well being. (laughs) I was on Saquinavir which was not the best of the drugs. And then I went onto the wasting ones, like 3TC and DDI. I’ve given up on the names. They ask me sometimes, “What are you on?” and I have no idea. It’s like you’ve had so many lovers you can’t remember all their names. (laughs) I’ve been on so many drugs, whatever. What’s your name again? Norvir? DDI? Yeah, I’ve been sleeping around with them all for quite some time.

I’m almost positive I seroconverted in 1982 in Haiti, because we had this very wild sex with a fellow by the name of Ti L’homme, who was anything but petit. I can’t imagine it was anywhere else, because the symptoms started showing up in 1985. I got shingles at the age of twenty eight, twice over the course of two years, in my legs of all places. It went on for months and I still have neuropathy from it. After half a bottle of red wine it’s like being plugged into an electrical socket. The disease is writ large across your body in so many different ways.

Alex Wilson planting seeds

Mike: Did you know in 1985 that you were HIV positive?

Stephen: My partner Alex Wilson was diagnosed with ARC: AIDS Related Complex. He was having night sweats and losing weight. He had a series of opportunistic infections on and off from1986 until 1993 when he died. I think because I’m a mongrel I didn’t get sick until quite late. I have the genetic superiority of mixed blood to get at these things from different angles, whereas he was a thoroughbred and they could take him out right away. But as soon as he died I went downhill.

Mike: Do you think there’s a relation between his dying and your health?

Stephen: Yes, it’s very depressing losing someone you’ve loved so deeply. This is someone I was with for almost fifteen years, someone I went through all of my changes with. It’s like having your heart ripped out. I lost both my roommate and my studio mate in the same week. I was sharing a studio with Rob Flack. I got a call in the morning that Rob was in the hospital. I got a call at eleven that night telling me that Rob had died. You know that story. Suddenly you have all this stuff to deal with; a person’s life doesn’t stop just because they’re dead. It was total reality. Everything was so real every day. You could operate, but it really did affect your world view knowing that every day could be your last. How did you manage?

Mike: I was on a countdown. Because I’m an optimist, I thought I would have ten years which would make me, in the words of that time, “a long term survivor.”

Stephen: That was the prognosis. Basically everybody died after three years though. (laughs) The decline is gradual except for the occasional crisis. You normalize things and distantiate. Denial is your friend. People would tell me I was in denial and I would ask them: What is your strategy for dealing with this? Embrace it? “Oh woe is me, I’m going to die today, or the day after.” No, I’m like you, glass-half-full guy.

Mike: I think I would have found it a lot harder to embrace my denial if I was living with somebody who was in such bad shape.

Stephen: There was too much work to do to care about oneself. There were diapers to change, medicine to pick up, arrangements to be made. During the last year I was basically taking care of Alex eighteen hours a day. I was running his career because his book had just come out, and we had a landscaping business. And then there was my own career. The physical aspect of taking care of him was very demanding. Six months before he died I had an exhibition, and finally I had to leave and install my show. I left him with Colin Campbell who flipped out. He had no idea how much work it was. Alex was an adult but he couldn’t do anything. He couldn’t cook for himself, he could barely walk. Nobody knew until then. That’s when John Greyson mobilized a care team who took over the daytime schedule. We went dancing a lot at Go Go’s, so every Wednesday somebody would stay at the apartment, while I would go out and take drugs and drink and dance until I wanted to come home. Alex had a pajama party every Wednesday so I could leave. It was the best way to get out of your head. How did you distract yourself?

Mike: I overworked. I had a job at the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre, so I thought: why not work seven days a week? I shared a studio with friends just around the corner, meaning I would never have to go home. Home was a room that was empty except for a single backpack with clothes and a couple of books. No telephone, computer, electronic devices. The important things in my life – film, camera, rewinds – were at the studio. I was forever working on “the last film I’ll ever make.” One after another.

Stephen: It was kind of fabulous, you didn’t put up with any guff. I’d already decided that I was going to be an artist, but this period cemented my resolve. I’m going to die tomorrow, so I don’t want to be caught up doing things I don’t want to do. Life is short, the future is now, let’s get on with it. I got the call early and picked up. So many people work their whole lives and save their money thinking, “I’m going to retire, and then I’ll do all the things I want to do.” Not me. I’m from the hedonistic seventies. It’s all about aujord hui. Tomorrow is just a broken promise, I’m sure.

Mike: Something they sing about in French songs.

Stephen: Exactly. (singing) Rien de rien…

Mike: I found it hard to be clear about the work I was making in that pressure cooker.

Stephen: You mean the external pressure?

Mike: The internal clock. You’re dying, you don’t have time, finish this now. How can I allow a work to unfold in its own way? It was a difficult moment to learn patience and abiding. When I look back on the movies I made, and there were plenty of them, but I don’t think they were very good.

Stephen: Have you seen them lately? There’s nothing like urgency. And there’s something so evocative of a moment that can’t be translated into nostalgia. That work carries all the subtleties of its era. So it might be interesting to look at them again, just as a document, because you were responding to things as they were happening, and there’s probably some kind of honesty there, even if it’s the not the most aesthetically pleasing. You can always tweak it digitally now.

Mike: That’s definitely what I don’t want to do.

Stephen Andrews, Self portrait as an after-image 2 2009

Stephen: What did you do when you realized you were Lazarus? When they rolled away the stone and said, “Come out.”

Mike: I had a very reluctant relationship to drugs. As my counts lowered, my doctor begged me to go on AZT, the only drug available then, and all I had to go on were my instincts. I refused, which turned out to be a good decision. When the cocktail finally arrived my counts were… I know they’re in there somewhere, if we keep looking.

Stephen: There were so few you could name each one.

Mike: My health dramatically improved, I had the initial “I feel shitty” period too, but it didn’t last so long. That wasn’t the difficulty, as it turned out. I had set myself on a ten year path and it was difficult to let that go. I’m still grieving the fact I’m not dead. In the past couple of years I’ve had several friends die, and part of what makes that unbearable is that it cuts against the old deal. Dying young means I don’t have to watch my friends die.

Stephen: When Colin was dying I felt he was pissed that I wasn’t already gone. He had done all this worrying about me, and then suddenly he was checking out before me. There was a certain kind of animosity directed towards me at the end. It’s something I could recognize because I had other friends who were in the same boat, but maybe not as far down the river, and I became angry, even resentful, at their relatively good health.

Mike: You mentioned a canoe trip with John.

Stephen: That was the trip I described before the cocktails arrived. It was in August 1996, the cocktail came a month later. We had heard rumours at the beginning of the summer about a drug cocktail with protease inhibitors. But it wasn’t clear whether it would be made available in Toronto. And there was no guarantee that I was going to last that long. I promised John when I went on this trip that I wouldn’t get sick, so I was full of Septra to prevent things going sideways.

Everyone was pissed off at John because we were going kayaking for two weeks off the Haida Gwai. I was of the mind that you might as well go to heaven first and then die. Who cares? This was obviously unfair to John, but he seemed to be a completely willing victim, in case I croaked. What I didn’t tell him at the time was that huge chunks of my vision had gone missing. The visual field had holes where there wasn’t any information. And because I was on Septra and we were outside all the time, I turned red as a lobster.

We had an amazing trip. We had been out in eight foot swells on the Hecate Strait. The waves were too big on the shore to put in anywhere so we wound up paddling forty kilometres that day, and pulled in near Rose Harbour just as the sun was setting. We turned into the strait facing into the sun, and I had a strange hallucination where “going into the light” wasn’t about dying, it was about coming out of darkness. It completely retooled my thinking about what was going to take place. I thought “I’ll go home, take the drugs, and be ok. It’s not a shutting down, it’s an opening up.” I was completely convinced of this, it was a very beatific moment.

We came home, I went on the drugs, and got better. But what I hadn’t anticipated was the difficulty coming back from that brink. It took me three or four years to put Humpty Dumpty back together again. I had imagined I had finished my art work, that it was a good time to go. But when that didn’t happen, how to start again from below zero? It was time to rebuild a rationale.

So much of my sense of self is about being loved and I had lost my love. I thought: I’m down a pint or two. Who is going to love me again? How will I live when I can’t be loved? It was a very difficult moment. It wasn’t until 2000, after John and I got together, that I understood what this Lazarus thing was about, this coming back to life. It’s about being loved again. That became an allegory for the stone rolling back. It wasn’t just regaining my health, but being loved. That’s when I felt alive again in some profound way, and found a new place to work from.

So much of my coping mechanism in the years prior to Alex’s death was about reading Rumi and finding spirituality through love; the physical-emotional love he articulated. Somehow that had gone missing in my thinking about how to regroup. In 2000 I found Rumi again, and his thoughts about seeing oneself reflected in the jewel-like eye of the beloved. That’s when I could make something that mattered to me, not just a rehash of old ideas.

Like you, my work defines me; that’s what being alive is, it’s about working. Processing the world through making things. It’s like thinking out loud. Thinking in material ways. You must have gone through some version of that experience to piece it back together again. You described living out a countdown, charging towards an end point. I was doing that aesthetically, and thought about it in mathematical terms. I had painted fax portraits made up of zeros and ones. I wondered how that could be further reduced. I was trying to distill experience to its essentials. After taking chiaroscuro out of the line, what is the next logical step? Working at the level of the pixel. And what is a pixel but a numerical representation? So I made drawings using numerical representations. Then you get to zero and there’s nothing left, and that’s why I thought I was ready to go. I had reduced the work down to its endgame, which was a trap that I was going to get out of by dying.

When I came back to life, I started to think of the zero as a lens. Everything goes through this focal point and comes out the other side. That’s when I became even more interested in materials and processes, and understanding that the gift of life is material. I didn’t need to get so caught up in denying oneself materiality. I thought that’s all this is, existence is just stuff. Might as well have more nice stuff. Make stuff, get stuff. John and I would laugh when our Portland friends would tell us about Rajneesh who said, “I believe in materiality and spirituality.” I totally buy that!

X-men at Union, 2012

Mike: The way you’ve painted light and bodies in the last half dozen years feels familiar to me because I was positive in that pre-cocktail moment. I can’t help feeling that all of us were that light, and I’m not speaking metaphorically. Light didn’t simply appear on bodies, I saw the way bodies emit light, particularly when they’re dying. It’s amazed me that you’ve been able to take this culture of dying and transplanted it, using it as a lens to re-view contemporary events like the Iraq War.

Stephen: Elle Flanders said something similar. I found it shocking at the time. Is that what I’m doing? I thought the work was about life. But you need contrast, you use darkness to describe light. If you look at the paintings, they are given over to describing nothing, the white blank of the canvas. There’s nothing at the heart of the matter. I haven’t done anything to this emptiness, I’ve only described everything around it. It made me think that the earlier work, which was explicitly about death, was made only to describe the light. What is that light? It’s intangible, conceptual, ethereal, pregnant with meaning. Everything is described except the thing itself.

There was an Inuit woman who was trying to explain something to western TV producers, and you know TV people, they’re always hoping for a short cut. This woman described everything around the answer, and if you listened closely, and gathered up all her facts and thought about them, you’d be able to answer the question yourself. Her approach was: I can’t tell you the answer because you won’t learn anything and it won’t mean anything to you. I thought this was a great approach, describe everything around the idea, and then others can fill in the blanks.

Now that I’m at the beginning of old age, the prospect of death has been the big “So what?” for so long, that while others are pondering mortality in a new way, our articulations are more sophisticated. We’ve lived through the possibility of death at a young age, amongst people who thought they were going to live forever. Youth generally behave as if they’re bulletproof, but even when we were young, we knew we weren’t. It’s not like we have more answers, but I think we have better questions.

Now I’m into reflections, I don’t know what that’s all about. Maybe it’s a self-reflexive moment. Maybe it’s about mirroring, or the surface of things; how the materiality of things represents the gift of life. I think of this new work as philosophical, while the earlier work is existential.

Mike: The Rumi quote suggests that when I see you, I’m also seeing myself, because we’re already parts of each other.

Stephen: That’s the hardest part to get, particularly for young people who don’t understand themselves. When you’re part of a group, and people in the group die, not only do you lose them, you lose what they remembered about you. And if you don’t fully understand yourself, then you’re doubly bereft. Suddenly you start to feel the hollowness in yourself because your past was backed up by these people. Maybe you didn’t even know it was there sometimes. They might offer unwanted reminders like, “Remember when you…?” And you’d reply: “No, I would never do that.” But everyone else can triangulate the moment and assure you that it really did happen. It’s about being known. If you don’t have people who know you, then who are you?

It takes a long time to develop this kind of friendship. People that see you for who you are, so you can’t pull the wool over their eyes. Someone you’ve met a couple of years back might suddenly make a strange move. You’ve only known them a short while, so the errant moment looms large. Whereas if you act up and someone’s known you for thirty years, they can let it pass. Oh, you’re doing that thing again, I pre-forgive you. Whereas the person you’ve known for two years has already decided not to pick up when you call.

Mike: Could we could talk about your art work and how it shifted in the 1980s?

Stephen: My mature work began with the realization that I was HIV positive.

Mike: What does mature mean?

Stephen: There’s a clarity of voice, a command of materials and a level of expertise that coalesces. You can look at something and say: this is where it began. What came before was student work or young work.

Mike: Did it feel like you had found your voice?

Stephen: It was a voice amongst many in a community where I felt connected to what was going on and was busy depicting that.

Mike: Were you part of a collective enterprise?

Stephen: I finally started to feel like I belonged, but finding a community was difficult. While the gay community had gained rights and visibility there was a struggle for life and trying to find meaning. When you become positive in your twenties you’re forced to think about mortality in ways that you’re not ready for. I don’t know that anyone is ever ready, but when you’re young you think you’ll live forever. I used my work to process it all. I don’t think of art as therapy, but it is a way of externalizing ideas and emotions. Working instinctively creates an artifact of what your unconscious is revealing. Community, seroconversion and a certain accumulation of skills coalesced in the late eighties.

Narcissus, 1989

I think the first work was a group of drawings called The Adam Suite. This was a set of sgraffito drawings in wax, still mulling over the body. I had been looking at scrimshaw, that’s where you scratch drawing into bone and rub candle soot into it. An old mariner’s practice. I wanted to find a way to do that in two-dimensional drawings. I coated paper with wax then scratched the drawings and rubbed oil into the scratches. It was a kind of tattooing, a metaphoric writing on the body. That was the beginning of my mature work. I’d also stopped shopping around in other cultures, and started using my own for the content of the piece. The Adam Suite was about how God made the first man out of clay. “Adam” is a play of words on clay, it means clay in Hebrew. I was mixing up Frankenstein (the making of a monster), the chapters of Genesis where man is created, and the role of the artist in making things. It was the first time I used a polyvalent approach to making work, weaving together disparate narrative threads. For the first time there’s a sophistication of meaning, where the drawings can be taken in a number of different ways. They’re also just beautiful things, you can look at them without interpretation.

Mike: I’m wondering about the relationship between me and we. Is exhibition a way of remustering community, giving you a sense of orientation, or even the new compass of unexpected conversations?

Stephen: Perhaps community is an overfreighted word and conversation is a better term. Community is about audience and I don’t know if I’m so concerned with that area. We’re in the game of communication, but I don’t anticipate their response, I’m not working towards that goal. It’s more about following the gravitational pull of the work, learning something for myself that I can share with friends. Hopefully one or two people I don’t know dig it too, and you actually communicate something.

Mike: You often work in series or sets.

Stephen: I did until recently. I was thinking about sentence structure, individual works were like nouns or verbs, they could be organized into a syntax and meaning evolved out of that. Now I’m doing paintings where each one stands on its own, it doesn’t require other paintings to flesh out its meanings. I started working in series because of feminism’s distrust of the masterpiece. Art history is liberally seeded with patriarchs who made heroic gestures in paint. Painting was a longstanding private joke, something I swore I’d never do. To use the words of one of my teachers back at school, “If you can’t do it right, do it big and in colour.” That’s what I’ve been practicing. It may not be right, but it’s large and shiny so all the rich birds can bring it back to their nests.

Mike: You’ve described your work as moving towards a reductive finale as you became increasingly sick with AIDS.

Stephen: You didn’t do this too? You didn’t come to a conclusion?

Mike: My approach was hysterical, not least because I hadn’t arrived at my mature style. I hadn’t been born yet and I was already dying.

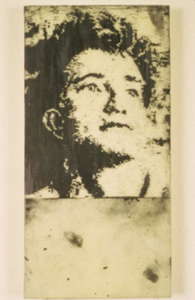

Facsimile

Stephen: Between 1991 and 1993 I made Facsimile, which is a ten dollar word for fax. It was titled by Andy Fabo. I might have wanted to call them Proofs, but he said, “Oh they’re like fascimiles,” and I realized, “Yes, they are fascimiles, that’s what it’s called now.” There was no AIDS memorial at that time. The crisis really hit Toronto in 1986. People had died before then, but that’s when the numbers started to escalate, and by 1989 people were dying every week. I’m not telling you anything you don’t know. What’s hard to describe is what it was like to get up and go about your day in that climate. Because we were so young, no one had a skill set for dealing with death. It was very dramatic and scary. The one thing that mediated the fear was the amount of work that had to be done. You could throw yourself into the fray, the ignorance that had to be fought against, the medical profession that had to be wrangled. There was public hysteria and unbelievable stigmatization. It was a very intense number of years.

One of the things that separated the Canadian experience from the United States was that we have a health care system. Even though some health care professionals were fearfully anxious, you could deal with various infections. Whereas in America it’s so Darwinian, groups like ACT UP (Aids Coalition to Unleash Power began in 1987) were born out of necessity. There was a safety net here, so the artistic responses were softer and more philosophical, less agit-prop, more poetic.

I had been working on the chiaroscuro graffito drawings I mentioned. Formally, I aimed to simplify my representational means as the crisis got deeper and the emotional pitch went higher. I had wanted to do a piece about friends and colleagues who had died, in order to start processing the grief. I didn’t initially think of Facsimile as art at all, but as a memorial. In the late eighties, Xtra Magazine started publishing a column named Proud Lives. My partner Alex faxed me a copy of its first appearance. When I received the transmission I was blown away because this brave new technology had forgotten the image. We rely so heavily on our machines as prostheses for our memories, our cars have become our feet, the computer our nervous system. At that time fax technology was the latest thing, but it had rendered all these snapshots of loved ones, reproduced via half tone newspapers, as crude, high contrast impressions. It presented a generational wearing away of the image, as if each generation signaled a passing of time. It seemed so ripe with meaning, and soon became the subject of a series of portraits, engraved into wax with a jeweler’s screwdriver. It was a very mimetic process. I was imitating the fax portraits, but using a material that spoke about death. Death masks are made with wax, and Egyptian funerary portraits. From a distance they look like they’ve been spit out of a machine, but when you look closer you realize these are complete labours of love, taking many hours to make. I’d work on a part for eight months or a year, and then I’d think the piece was done, and then more people would die, and I’d do another section. This went on from 1990-93. There are 151 portraits in four parts.

Facsimile part 4 (detail, Tim Jocelyn)

Mike: Were the portraits named?

Stephen: Yes, I wanted the series to include aspects of traditional memorials, it even has music. But like the drawing itself, I pulled my punches. I didn’t want to have any kind of line that would be freighted with emotion. The subject was so emotional all by itself, to use flourishes or little tricks would have completely undermined the intent of the piece. I approached the music in the same way as the drawing. I found player piano rolls, which is a proto-digitalization of music. Like early computers, they ran off sheets of paper with punchhole notations. I found music appropriate to the piece like Auld Lang Syne (Lest old acquaintances be forgot) and Sweet Remembrances. There were four altogether.

The portraits were put up in a grid, three to a row. Directly underneath, the piano rolls were unscrolled, bearing the names. Everyone’s name was printed with stamps so the trace of the handmade remains, but there’s something between the hand and the image, between the word and the hand. A mechanized coolness is introduced, an attempt at the rational, which creates tension because the situation is so emotional and the author is so involved in it, so it’s a sort of ruse. I’m trying to be objective, trying to create order out of chaos, but it’s a fool’s errand, and all of that is in the piece.

Facsimile became a memorial. People who rarely set foot in galleries came to see their sons or daughters. When I showed it at Carla Garnet’s gallery for the first time, everyone stayed downstairs talking and drinking, while visitors would go up to the second floor one or two at a time to see the show. Standing upstairs amidst so many dead people with the party sounds below was awesome, it was as if everyone was still alive. The piece was done on bees wax so it smelled like honey, it was very sweet. When I went upstairs there was an older woman, probably in her 50s, staring at one of the black pictures. Sometimes the image wasn’t there, so I put up a placeholder, a black image in the same format as the others, with the name underneath. She’d come looking for her son and found him there without a face, and I apologized for not doing a representation of him. She said no, I’m so glad he’s here. It was deeply moving. In a climate of rejection and disavowal, I felt this was a useful thing to do.

There was a lot of anti-sex talk in the air, and information about the Fruit Machine was coming to light. In the 1960s a series of tests were administered to weed queers out of the civil service, ostensibly so they wouldn’t be prone to blackmail. A series of pictures were presented to the subject that were supposed to cause pupil dilation and palm sweating if you were gay. I was very interested in pictures that would make you sweat. I had figured out how to make pictures that made you cry, now I wanted to make sweaty pictures. I started to make photocopy transfers of sex pictures on rubber and called the series Safe. I knew they wouldn’t last but didn’t care, they would doubtless be around longer than me so who gives a fuck? I made those concurrently with the fax portraits.

That’s how we got to 1993. My partner Alex died, everybody died. It felt lonely, so I started making work about finding a new love. Personals were big at the time. I began reading personal ads, fascinated that so many people were doing without. I started doing imaginary portraits collages. I would take high gloss black and white magazine photos of people and fold them into simple little origami boxes. They start out flat but when you blow into them they become 3 dimensional. The photos end up looking like little heads. These I would hang on the wall with a ribbon of paper. Below each ‘head’ I would pin a little personal ad clipped from a newspaper that would describe what they wanted in a lover. Some of the personal ads are very funny, or sad, or explicit. I showed that piece all over the world, and wherever I went I would make new ones. Japan, England, Holland France. There were hundreds of little boxes pinned to the wall, and you could read the texts as you liked. They seemed to speak to the zeitgeist.

Once again there was restraint and a resistance to gesture which I thought was too seductive, too problematic. I tried not to show my chops. I still wanted to seduce people, but I didn’t want them to know it was happening. The way to get things out of people is to have them think it’s their idea. I’ve been a master of that for years.

In this formal exercise I’ve gone from chiaroscuro gestural lines to contour lines, to dash and dot pixels. Then I started making number drawings. I would take photographs, drop a grid over them, and assign a number to each of the squares. This was before digital technology. I had been looking at Ellsworth Kelly’s paintings from the fifties and they appeared digital. People seem to feel there’s a connection with Chuck Close but I wasn’t really looking at that stuff. I did all these drawings of numbers that were representations of photographs, usually of loved ones. The idea was that memory fails, even technology fails, but if we have this map, sometime in the future we could reconstitute the image and it will be exactly like it was. Once again, a fool’s errand. The work evinced a hope against all odds that one might be able to reconstitute life, it was a David and Goliath response to unimaginable crisis.

This was the final piece of my endgame, many other artists have played out their own versions. Look at Robert Ryman’s white paintings: at some point you can run out of variations on white. Ditto for Ad Reinhardt’s black paintings. What happens when you reach the end? I needed to come up with something completely new. I thought I would move away from the schematic, minimal, DADA practices into overheated paintings. Do you know Picabia’s baroque oil paintings?

Mike: No, but I’m thinking about what happened to the painter Frank Stella. His early work was so perfect that all that was left for him was a lifetime of producing increasingly extravagant rubbish.

Stephen: It’s better to start out shitty, like me.

Mike: It took me years to make something watchable. There was room to grow.

Stephen: When you start at the top there’s only downhill.

Mike: And then you have to work against the shadow of your own genius past.

Stephen: By the time I’d got down to the number, I’d reduced lines to pixels. What’s smaller than that? You can represent a point on a line by a numerical value. I’d got to zero and thought it was time to go. Then the pharmaceuticals arrived and swapped a certain death for an uncertain one and I wondered: where do I go from here? I decided to think of zero as a lens, an oval through which experience switches, turning everything upside down. I could start again by making little transfer prints with my fingers. These were fingerprint drawings with forensic science attached, the portraits had the whorls of my fingers imprinted into them, conjuring the stigmatization or even criminalization of HIV-positives, even though the portraits didn’t necessarily show positive people.

Mike: I’m wondering if you could say something about cinema.

Stephen: My arrival at the moving image was through the back door. I’m a back door man. I live with a filmmaker and thought: that’s his department, I don’t need to do that. But perhaps in spite of myself, I began making proto-cinema work, breaking down experience into frames in order to explore narrative. Personally, it was about finding myself again, and moving from black and white into colour. I think we already talked about going on the medication and the difficulty of coming back to life and assuming some new role. I was trying to find a way to represent the Lazarus narrative. In order not to be the living dead, I had to be re-animated, and that happened through my love of John Greyson.

The First Half of the Second Half

The piece is called The First Part of the Second Half. Part of it is based on a Rumi quote about seeing oneself reflected in the jewel-like eye of the beloved. It’s in three parts, and features a series of quotations: Brakhage, Warhol, Jarman. There are a series of photocopies onto mylar sheets which hang from the wall like overblown film strips. The sheets are ten feet tall and six inches wide, and the frames are three by four inches.

It starts out with a title announcing The End. I blow up a balloon until it explodes in my face, and then a crowd catches fire and the countdown begins. After the countdown sequence the camera pulls back from glittering shards until you realize it’s a diamond, or the jewel-like eyes. And then it becomes a figure in an eye, and as it continues to pull back John is revealed. A love scene follows, appropriated from a Joe Dallessandro porn moment showing Joe getting fucked, something he denies ever having happened. A friend of John’s found it playing in a New York bar. By the time we saw it, it was already a copy of a copy of a copy. That section ended up getting censored when I showed it, and wound up being better for it. Gallery officials were afraid of children seeing it so I made circles that covered the naughty bits and overlaid them. Of course the kids lifted them up right away, they just want to see the junk. Handsome Joe flip flopping.

The final section is called The Future and it’s entirely blue, in reference to Derek Jarman’s Blue. I worked from 1996 to 2000 to figure out how to represent these ideas of love, cinema and resurrection, and that got me back into the game.

From there I moved into animation but not of my own volition. The Inside Out (LGBT) Festival invited a bunch of artists to make animations. They offered technical help, and asked for delivery of a one minute animation in a couple of months. I did a ten second pencil test and my wig flipped off, it was so exciting to see the drawings move. What you draw and what it looks like on screen are two completely different things.

The Quick and the Dead (1.5 minutes 2004) was sourced from footage that Ali Kazimi found for me, raw footage of someone with a camera walking with a platoon in Iraq. They’re all hyped up, the wind is blowing, the grass is moving, death can come from any direction. When the American soldiers hear rustling in the grass they don’t ask any questions, they send a rocket grenade towards the sound. One of the soldiers has to go over and clean up the mess. It turns out an Iraqi soldier was having a sponge bath by his motorcycle. When they fired the grenade, the gas tank exploded and killed him.

My animation replays the scene in three shots in order to produce a Cain and Abel story. The American soldier kills the Iraqi, you see smoke in the background, fade to white. Then there’s a fade in on this strange, mangled form and some flames. At last you can see a naked body on fire. Fade to white. The final shot shows a soldier walking into frame with a fire extinguisher. He steps over the corpse to put the fire out.

This short narrative about two brothers doesn’t pass judgment on either of them. The pictures I didn’t select show body parts, a face blown off, it’s pretty horrifying stuff. The one putting out the fire has to deal with these images, I’m sure he was deeply traumatized by the experience. The work is presented as a looping video installation which shows the fire being put out again and again. Perhaps the piece is saying: you can start a fire but you can’t put it out. It took me a year to make the seven hundred drawings, and the movie is just over a minute long.

Mike: You make this awful event look so beautiful.

Stephen: The sublime is terrifying and beautiful. It’s the abyss. You hear the call and try to resist. It’s something you can’t not look at, but you don’t really want to look.

Dramatis Personae

Mike: Could you say a few words about your most recent movie Dramatis Personae (6 minutes 2012)?

Stephen: Imagine a credit sequence for the sixties. I was inspired by True Blood’s credits, I think it’s one of the best experimental films made in the last decade. The TV show is about vampires, but the opening doesn’t tell you anything about the show, instead it sets up a mood. Other inspirations include the scene in the movie Gimme Shelter (1970) where Mick Jagger and the editor are going over the knifing of gun-wielding Meredith Hunter by Hells Angel Alan Pessaro. They were trying to determine who murdered who and where was the gun, using the film as a forensic tool. And there was the most famous home movie of all time, the Zapruder footage showing the Kennedy assassination. For me those were the brackets, a moment when innocence is lost in America, and I stopped being a child.

The work was commissioned for the opening show of the Ryerson Gallery, home to the Black Star Collection, approximately 300,000 photographs that offers a history of the twentieth history. To find some purchase on that mountain of history was difficult, I wound up showing events that took place during my lifetime and informed me. I wanted to allude to the people that make history but aren’t necessarily recognized, you might know the photograph but not the person. Those are my dramatis personae, and they are named in the film’s opening. The name of the naked Vietnamese girl who was napalmed. The name of the burning monk. The name of the busboy holding Robert Kennedy’s head. Hibiscus was the boy-man who put a flower in the National Guardsman’s rifle. Sergeant Ron Haeberle took a lot of the photographs in My Lai, Vietnam, site of an American massacre in 1969. Michael Collins was the Apollo 11 astronaut who went to the moon but stayed in the capsule. Those are the sorts of peoples I was interested in recalling. There are so many others but I could only select a few. The piece is a tone poem about the state of emergency that was the sixties.

The glue for the images is a flashing light, it’s all shot on 16mm film and hand processed. My brother made a solo drum soundtrack as if to say: the beat goes on. It’s hard to show because Black Star owns the pictures, so I’m not allowed to exhibit it outside the gallery. But you don’t really make money out of films anyway, do you? That’s why making animations was perfect, I had all those drawings to sell. Give the animation away, sell the drawings.

Mike: You mentioned you were working on a new series that was about reflections.

Stephen: It’s still in process so I don’t know what it is. I try to not know what I’m doing while I’m doing it. If the lessons are learned then what’s the point? For me it’s all about learning something new.

Mike: I’ve been thinking about that a lot lately. There are two things that seem important in an artist’s practice. One is that you don’t realize the project too soon because it closes off possibilities. And the other is that you don’t know too late, overworking a riff. Each project has its own temporal ecology, its own local time.

Stephen: It will be interesting to see how the work evolves. I’m working on a bunch of new drawings, and a couple of new paintings. That’s where it begins.