The Patient Storm: an interview with Dana Claxton (2007)

Mike: I wonder if you could tell us about the place we’re sitting right now. Who does this land belong to? Whose property are we appropriating right now?

Dana: I thought we were going to talk about me. [laughs] Traditionally, it belongs to the Salish, who are a Northwest coast tribal people. There are four or five urban reserves that surround Vancouver. The city is still considered unceded, it’s part of an ongoing land claim process. The Salish are negotiating with all levels of government, which is tasked with reconciliation as well. It’s interesting living in a place where we have modern-day treaty making. It’s part of the colonial legacy, I suppose.

Mike: In a Georgia Straight interview you said you preferred the term “Indian” as opposed to “Aboriginal” or “First Nations.”

Dana: My older relatives always used the word “Indian” as a consistent, casual word. It’s not loaded when we use it, as aboriginal people. Although certainly it can be like the N word if used inappropriately. It depends on who’s saying it and in what context. When I talk about “Indian people” or “Indian culture,” it’s seems like a normal term to use, as opposed to “First Nations,” which I think is some sort of invention. I’m comfortable with “Aboriginal” but others aren’t. Some Native people don’t like the term “First Nations.” So it really depends on what people are comfortable with. Sometimes my students say, “We’re confused. Which term should we use?” And I assure them, “It depends on who you talk to, you have to ask them… and good luck!” Because everybody has a different term that they are happy with.

Mike: You’re teaching a course at the Emily Carr School of Art and Design. Is it called The History of 20th Century Indian Art?

Dana: It’s called The History of 20th Century First Nations Art.

Mike: I’m guessing that within that history, the flourishing of media art has been relatively recent. When you started producing work more than twenty years ago, it was rare, wasn’t it?

Dana: I think Indian media art has been around for almost 25 years, but whether or not it’s been identified as a bona fide practice is another thing. There were practitioners before me and certainly there’s a lot more nowadays.

Mike: Can you talk about how you got started?

Dana: I didn’t study film formally, but I was always attracted to the moving image. Being self taught, I’ve accidentally broken a few rules. Inside the house where I grew up, there was an early fascination with television, while outside, the enormous Plains sky provided a whole other visual culture. One morning, when my sister and I were driving home to Saskatchewan, we stopped to buy a super-8 camera and a couple of rolls of film. We shot a typical, homebound road movie on our way. Grant Her Restitution was one of my first works and parts of it went into many other projects.

I began working within an artist-run-centre context, primarily with the Pitt Gallery in the early 90’s and Video In, even though I liked shooting film. Video In was started in 1973 so that artists could gain entry into this powerful medium of “broadcasting” and have accessible tools. They also hosted screenings and Sara Diamond ran critique nights which were very engaged in theoretical aspects of video making, video art as resistance, or video art as identity politics. We looked at different genres that had emerged from people making video as art from around the world. There were always great discussions about that kind of thing.

When I popped onto the scene, there were still strong divisions between film and video. Some video festivals refused to show anything that contained film, while specialized production centres divided communities of makers. I loved both formats. In fact, I think I have the only film that both Video Out and Vtape distribute. An actual film! Not a film to video transfer. Video In has allowed me to transfer film onto video, that’s where I’ve edited and will continue to edit all my work, unless I’m making larger projects and need a more complex system. They’ve been very supportive and Winston Xin and I are very comfortable there.

Mike: Winston Xin has been your editor for many years now. Did you meet him there?

Dana: Or did I meet him at Holt Renfrew? We like to shop as well. [laughs] We met about 13 years ago at Video In where he was programming and making his own work. We’re about to set out on our first full collaboration together with the Vancouver Queer History Project which will look at the history of gay night clubs in Vancouver, along with dance anthems.

Mike: When you started working together, video editing was “linear,” which meant that you couldn’t go back and make a change in the movie, unless you wanted to re-do all the edits from that point on. This meant cutting with a degree of certainty that is almost unthinkable today.

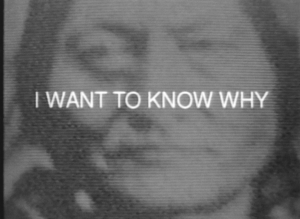

Dana: Yes, it requires a great deal of trust and knowing. I Want To Know Why (6:20 minutes 1994) was made that way.

Mike: The tape begins with a gauzy close-up of a face I imagined might be your great grandmother.

Dana: That was actually a black-and-white, super-eight shot of the front page of the Globe and Mail newspaper. It showed a warrior on the one-year anniversary of the Oka crisis. The crisis arose out of a land dispute between the Mohawk community of Kanesatake and the town of Oka, Quebec which began in July 1990, and lasted until September. The Mohawk nation had been pursuing a land claim that included a burial ground and a sacred grove of pine trees near Kanesatake. This brought them into conflict with the town of Oka, which was developing plans to expand a golf course onto this land. The front page showed an Indian man with full war paint on, talking about the land.

Mike: Its framing and soft grain renders it dreamily iconic, as if it’s an enduring image from a long time ago.

Dana: Many of the tape’s powwows and teepees were shot that summer in Saskatchewan, though a lot of people thought they were archival because of the black-and-white super-8.

Mike: When you traveled there to shoot, did you know that you were working on this piece?

Dana: No, I was gathering material that might be used later.

Mike: Your tape is a kind of home movie for a family that never quite had a home. Instead, there are markers placed where home might have been. On the left side of the frame there are three Indian heads stacked in totemic fashion. They look on with eyeless eyes at a suite of Indian dwellings, mirrored images of fences and enclosures, and Indian portrayals on public buildings. The way in which certain moments of Indian history are frozen into public architectures is a recurring theme in your work.

Dana: Some of that was shot while I was living in New York’s Chinatown. I looked up at the Manhattan Bridge and saw a beautiful relief with warriors on horses chasing buffalo (Buffalo Hunt, by Charles Cary Rumsey). Across the street is one of the biggest American banks with the same Indian men on “wounded knee,” holding up a clock. When I turned to look the other way, there was a huge teepee at a homeless camp. At this busy intersection where four or five streets come together, I found all of this representational architecture, and the teepee and the reliefs of Native American people. But even in these moments of visibility there is still erasure going on. The history embedded in the architecture, for example, shows how the static image of Indian people persists, but remains absent from contemporary consciousness.

Mike: On the soundtrack we hear a voice, is it yours?

Dana: It’s me, yes.

Mike: You say, “My great grandmother walked to Canada with Sitting Bull, starving.” Then you scream the tape’s title, “I Want to Know Why.” I’m wondering if you could tell me about Sitting Bull’s relationship to your great grandmother and the walk they made together.

Dana: He was instrumental in the Battle of Little Big Horn, where, as we say, they “took out Custer.” It was a confrontation between a Lakota-Northern Cheyenne combined force and the 7th Cavalry of the United States Army. It occurred on June 25/26, 1876, near the Little Bighorn River in the eastern Montana Territory, close to what is now Crow Agency, MT. It’s the most well known battle of the Great Sioux War of 1876-77, and was a great victory for the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne, led by Sitting Bull. The U.S. Seventh Cavalry, including a column of 700 men led by George Armstrong Custer, were defeated. Five of the Seventh’s companies were destroyed and Custer himself was killed.

The Lakota had to leave the United States because they were labeled as the last “hostile Indians.” They were determined to continue fighting for their homeland. People were enraged after they took out Custer, because he was a hero to some. This was at a time when Indian hunting was considered an occupation and the American army had been mobilized against Indians. There had been bounties on Indian people paid five cents for every Indian nose brought in. ( This was a bit before, I will get you dates)

My great grandmother and her parents were part of Sitting Bull’s band and came with him to Saskatchewan. But the border was never formally there, of course. The border goes through tribal communities and families, so sometimes you have grandparents on one side and aunts and uncles on the other. On this basis, they felt the Lakota were as much Canadian Indians as American.

They came to Canada where they thought they would have political refuge because Sitting Bull’s grandfather fought for the Queen. The Lakota had been loyal to Britain during the battles for New France. As proof, Sitting Bull displayed a set of medals given to his grandfather by King George III for his support in the American Revolutionary War. In coming to Canada, Sitting Bull hoped to live under the justice and protection of Canadian law and be granted Canadian land.

Unfortunately, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald’s government refused Sitting Bull assistance. The government saw the Sioux as American Indians who had crossed the border into Canada and should be persuaded to leave. There were also tensions with the Blackfoot, Cree and Assiniboine, who accused them of stealing their buffalo and depleting game in their hunting ranges.

The Sioux travelled all over Saskatchewan, which is a lovely history. If one were doing a story on the Lakota Sioux and Sitting Bull, it would require visits to Moose Jaw and Standing Buffalo and up as far as Prince Albert. Sitting Bull was visiting people and there were little dust ups here and there. Many winters were spent in the Moose Jaw Sioux Camp, just outside the city. Some relations with settlers were very good and others weren’t. As tensions rose, the city dwellers didn’t want the camp so nearby. Meanwhile, and Sitting Bull were petitioning the Queen to get a reserve so they could move away from this camp. Sitting Bull went back to the South Dakota and eventually, we did get our reserve granted in Wood Mountain, Saskatchewan and my great-grandfather Oyewaste (Walks a Good Way) was one of the signatories. My mother was born on the reserve, along with my aunties and uncles.

There was a famous meeting in October, 1877, where Sitting Bull received a message from the American president asking him to return. If he would give up his arms and horses he would be granted a pardon and be allowed to return to his reserve. Sitting Bull replied, “For 64 years you have kept and treated my people badly. What have we done that caused us to depart from our country? We could go nowhere, so we have taken refuge here… We did not give you our country, you took it from us. See how I live with these people, look at these eyes and ears. You think me a fool, but you are a greater fool than I am. This is a Medicine House. You come to tell us stories, and we do not want to hear them. I will not say any more. I shake hands with these people, that part of the country we came from belonged to us, now we live here.”

Two years later disaster struck the Sioux — the buffalo did not appear. Without food from the Canadian government, Sitting Bull’s people starved, and many drifted back across the American border, accepting U.S. law and life on U.S. reserves. Others, including my relatives, stayed in Canada.

I grew up in Moose Jaw. The original camp was disbanded in 1921, though a local minister gave it to the city in exchange for a promise that they would build the Sioux children a school. But when the Crown granted our reserve, there was no need for a school there, so the land has been held in perpetuity. A lot of Saskatchewan has been clear-cut to make room for farms, so in terms of natural flora and fauna and bugs and salamanders and all those lovely, little creatures, they exist in this small preserve where the Sioux camp was.

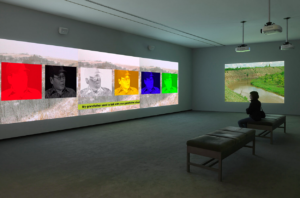

Mike: This history is touched in I Want to Know Why, but also in the four-channel video installation Sitting Bull and the Moose Jaw Sioux (2003).

Dana: The installation was commissioned by the Moose Jaw Art Gallery which holds a fascinating collection of Lakota work, pre-1900s. They have beautiful war clubs and bags and lovely things that I could access and incorporate into the work. Many scholars who research Sitting Bull eventually come to Moose Jaw and their research is deposited at the archives. The library itself holds an ongoing trove of Sioux history. The installation presents some of these materials, along with a sequence which shows camp descendants, many of whom are my relatives. They narrate a very open-ended story and recount different experiences they’ve heard and experienced. The video, which runs just over half an hour, features a mix of interviews and footage I shot around the camp itself. Much of this footage is reshot and reprocessed. I continue to do this kind of layering with a lot of my material.

Mike: The Hill (3:45 minutes 2004) is a single-channel work in split-screen which shows a woman trying to find her way into the parliament buildings, only to find doors which can’t be opened. She finally moves towards a statue and kisses it. Who does the statue show, and why were you in Ottawa?

Dana: That was made when I took my camera for a walk. [laughs] We were in Ottawa for a conference called Beyond Survival which followed the centennial of Christopher Columbus’s arrival. There were a series of conversations that began by asking, “Yes, we survived. Now what do we do?” Every Indian artist in Canada was at the conference. The women in the tape, Michelle Thrush (now a well-known actor for screens large and small), said, “Let’s go!” and I replied, “Bring something you can wear so we can both shoot, and I’ll bring my super-8 camera.” It was my first time in Ottawa and I’d never been to the parliament buildings, which was the site of many decisions that haven’t been the most favourable for Aboriginal people. She danced around the buildings, flirting with them, then tried to get in but couldn’t. This became a metaphor for not having access to power. There were statues everywhere and we chose one in particular. I don’t know who the statue commemorates, but I should find out because I always get asked that question. [laughs]. It could have been Diefenbaker. What was important was the way this big man sat with the parliament buildings behind him. It was very spontaneous. “Seduce the oppressor. Sit on his knee and kiss him.” It was going to be called The Princess of Parliament Hill because you go through a princess phase every now and again. It took me ten years to edit it. I have lots of material that hasn’t always made it into the editing room.

Mike: Tree of Consumption (11:47 minutes 1993) begins with a landscape study, a series of tree tableaus, and then the image itself is cut into pieces which offer us views of a clear cut in an elegant formal rhyme. A woman appears standing in front of a pile of rubble, and then the video lapses into a series of close-up abstractions. Everything is moving and alive and grieving, until at last we see her prone and naked on the ground, as if she has also been cut down. She wears a tree dress made by Kate Smith. Can you talk about this dress and the actions of this performer?

Dana: The tape was made for a performance called Tree Consumption. It came out of conversations around “unwise logging” and I wanted to make a response. I wondered, “What is it like being a tree?” Instead of a blade of grass. It was either a blade of grass or a tree. I decided to become a tree and Kate Smith made this lovely, long, green dress. In the installation-performance, roots emerged from the dress and led to monitors playing Tree of Consumption. I delivered the narration in fractured Elizabethan English, and spoke about the glamour of clear cutting, which is a forestry practice of harvesting all the trees in a single area. The narration was inspired by a full page ad in the New York Times showing a clear cut and asking, “How can we do this?” I thought, “How glamorous that they are taking out a full page ad in the New York Times!” The work was also about the relationship between violence against women and violence towards Mother Earth.

The footage was re-worked by shooting it off my television several times over. I had a fancy TV that would do all these picture-in-picture effects, creating frames inside frames. I’d re-shoot the original footage using special in-camera features. It looked very high tech when it came out, but it’s all done by playing around with home technology.

Mike: You mentioned the former divide between film and video. The reduction of that argument says that filmmakers care about how things look, while videomakers care about what they’re looking at. In much of your work you bring these two together. While each tape is grounded in an issue of representation, formal decisions follow which invariably sharpen these questions. In Tree of Consumption, your re-shooting brings out the grain and texture of the video, which at the same time it amplifies the “treeness” of the tree, and makes the performer’s body feel more embodied. It’s so very beautiful, and this beauty feels like something extra and unusual.

Dana: I like to play with technology and sometimes crisp, clear images aren’t enough. I’ve worked in the past to interrupt that flow, but sometimes I want to be open to that too. The People Dance (24 minutes 2001) is a surreal story about spirituality and infinity that blends the Lakota worldview with media art. It was shot on black-and-white, 16mm film, and offers a 21st century Sun Dance with everyone wearing Prada. It was shot like a Calvin Klein ad because I wanted Indians to look as glamorous as possible. [laughs] I get stuck in glamour sometimes because my mother ran a beauty salon in Moose Jaw. As children, we were all in front of the mirror, doing our hair. Popular culture and advertising offers another push in this direction.

Mike: Buffalo Bone China (12 minutes 1997) begins with a dark cloud of buffalos moving in a slow motion charge. Where is this footage from and why the slow motion?

Dana: I appropriated that footage from three sources: a National Film Board documentary, some footage made in Yellowstone Park, and Dances with Wolves. Once again, I re-shot off the monitor. I wanted the slow motion because it’s so beautiful to watch and allows viewers to get to know who this incredible being is. To study the form and movement of the buffalo. Some of our Sun Dance songs and Buffalo ceremonies all came from the buffalo, they are at the heart of Lakota tradition. White Buffalo Woman brought us our seven sacred ceremonies. They are considered our relatives, so their government-sanctioned extermination was very painful. Buffalo Bone China deals with this. It opens in slow motion and then becomes more urgent and panicked as it becomes clear that they are being hunted.

Mike: The buffalo are seen in an aerial tracking shot, and instead of thinking, “Isn’t nature beautiful?” it appears that they are being chased by the very technology that records them. What makes them visible is also what is killing them. The stampede sequence repeats four times before we see a hunter, the face of a bull, a man screaming, and a skull. We move indoors with languorous pans over china plates and cups and then a man sits at an elegant table waiting for a dinner that never arrives. Who is this very androgynous man who looks like he is wearing two faces, one on each side, and why the china?

Dana: He was an artist I invited to participate who represents Plains People because he was Cree. I think he was wearing a battered tuxedo over a pair of black pants and moccasins. He was there to look over the many dishes without food. Buffalo shank bones were sent to England to make fine-bone china even as my relatives were starving because there were no buffalo left.

This tape was also turned into a performance at Tribe: A Centre for the Evolving Aboriginal Media, Visual and Performing Arts, which partnered with the AKA Gallery in Saskatoon. I smashed an entire set of Royal Albert dishes, if you can imagine. I got in a bit of trouble over that. [laughs] The performance questioned what we valued: the tableware or the buffalo? In the tape, the artist sits at a table surrounded by incredible dishes, but there’s nothing to eat. He has been starved out, it has been well documented that both the Canadian and American governments knew that by exterminating the buffalo would starve “the Indian”. The wanted the Plains people to starve.

Mike: Untitled (7 minutes 2001) features a winning soundtrack by your musical mainstay, Russell Wallace. His drenching minor keyboard work floats over everything here. You conjure a quartet of speakers, who say, “And he opens his hand and there is nothing there, just the memory,” and “Who delegates freedom – do you?” and “Silence. He drives to the forest. Wandering, he sees his whole history in front of him, father, grandfather, all his grandfathers.” It’s a dreamy, poetic work that looks forward to a reconciliation between generations.

Dana: It is completely scripted and features actors I’ve worked with for the past twenty years. Samaya Jardey, has been in all of my films, and lately in my photo-based work. Sam Bob has been in several works, as well as commercial broadcast projects as well. They were actors before I became a filmmaker. I met many of them at Spirit Song, an Indian theatre company from the early 80s. A lot of us who had some sort of creative energy went there to work through traditional plays and interdisciplinary beginnings. Many of Vancouver’s performance artists came out of that place. We got a taste of theatre and some of us thought, “Okay, that’s not exactly for me.” The performative aspect of some of my work might have started there.

Mike: Was it more like a school, or a communal work place?

Dana: It was an Indian school so there was a bit of everything. It had a family aspect, a community aspect, as well as a training aspect to it.

Mike: 10 (7:20 minutes 2003) is based on the children’s nursery rhyme 10 Little Indians. We hear this nursery rhyme sung out in a series of cross-cutting, parallel episodes from a series of movies, all based on Agatha Christie’s 1939 novel which was titled Ten Little N…( the N word – this would be my preference to describe it. in the UK, and Ten Little Indians in America. In her novel, eight people are invited to an island where a host couple awaits. They are all guilty of murder somehow, though none were charged (one botches a surgery, one withholds medication and is thereby able to claim an inheritance, etc.). All of them die, one at a time. What is the significance of this song, and why did you intercut these different screen adaptations?

Dana: It sounds nasty, doesn’t it? It was made for the Media Art Biennale in Poland and curated by Winston Xin for a program called Stealing to Subvert. The idea was that you would steal footage and turn it around somehow. So I thought, “Okay, what do I do”? I thought of Ten Little Indians, and was surprised while doing the research that the song was so violent. [laugh] Then I found three different film versions, one made in the 1920s, another in the late 1960s and a third in the 1970s. Each shows the power of nursery rhymes and how harmful they can actually be. They’re anything but innocent. The song is sung in each version, so it was a beautiful tape to cut together. It was one of those projects where a lot was discovered while editing. Sometimes the work is completely scripted, and editing means conforming material to the shooting script. Other projects allow a play in post-production, and for a lot of my shorts, that’s what happens.

Mike: Each line of the song details the kind of death the next individual will suffer, until in the end, there is no one left. Is it an allegory of genocide?

Dana: Yes, that’s what it is. Before the song the guests sit around a dinner table talking about the colonel and his infatuation with the ten little Indians. They remark that he’ll be finished with them shortly because they’re all going to die. This history of colonialism enters with these comments, and then the song plays. Each movie version repeats the same lines, almost verbatim, allowing the nuance of performance to come through.

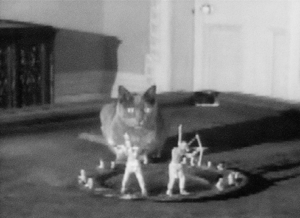

Mike: You’ve made a pair of movies featuring toy guns called Gunplay (2:45 minutes 2004) and Gunplay 2 (1:30 minutes 2007). Both are multi-screen efforts. The first shows an emptied child’s playground circled by a handheld camera which eventually finds a plastic gun on the ground with a Native head impressed into its handle. The second shows a trio of… is it you? The left and right screens show half a face, each in black and white, while the center screen shows you in full colour, playing with the gun in ways that are alternately amusing and threatening. You point it at yourself, and then at the viewer. The line between play and menace is blurred here.

Dana: The first began because I had my video camera with me and had gone to the park with my nieces and nephews. It’s their voices you hear in the background. You don’t see them, you only hear them. The camera approaches the playground and finds a little gun there.

Mike: So it’s a real found-object?

Dana: Yes, it was quite a moment. I had it for a long time, thinking that I needed to do something with it. And then the Columbine High School shooting occurred (April 1999), when two students killed twelve classmates before committing suicide. These little toy guns are not neutral, innocent items. They recall cowboy and Indian games, and all the racist child’s play that has been hidden — by manufacturing the same guns with the Indian-heads removed, for instance. The gun also suggests the real instruments used to kill Indians by soldiers or bounty hunters. When I did Gunplay II it was because I found another gun somewhere else. I’ve collected a number of them that I’m going to do a project with. There’s been a complete shift in the representation of Indian people on toys.

Mike: Anwolek-Regatta City (4:37 minutes 2006) show us a Kelowna street parade from the 1950s. Beauty queens float by in cars remade as giant swans while divers leap from the high board. It’s beautifully photographed and slowed down, and arrives with a lovely electronic soundtrack.

Dana: That was a commission by the Alternator Gallery in Kelowna. Anwolek is Kelowna spelled backwards. They were commissioning artists to make work that looked at the city’s centennial. I wanted to use archival material, and after going through the National Film Board’s Kelowna documentation, I purchased the regatta and parade footage. Although it looks so beautiful, particularly in slow motion, it’s very violent. The tape considers how land gets de-territorialized through pageantry. Kelowna is an ancient homeland for the Okanagan tribe across the lake who have their own memorial history and issues with the city. I wanted to look at pageantry and how you can take over someone’s land simply by having a parade, and occupying it with marching drums. It’s a very subversive work in many ways. The slow motion divers reminded me of people jumping from the twin towers. There is beauty and menace in the divers at the same time.

Mike: The Patient Storm (8 minutes 2006) shows two women, Storm and Lightning, in a white studio set. Storm represents tradition, and is mostly seated in a white Eames chair. Lightning represents action and change, and is played by a younger woman always in motion. Behind them you’ve projected a universe of stars. They are getting ready to descend to earth but are held up waiting for some latecomers. In the meantime, they talk. Here is your online description: “Storm is an elegant, knowledgeable patient woman. Lightning is a trickster type stylie, craxysexycool girlish woman who talks in riddles and rhyme. At the beginning of their conversation they are waiting for Wind, Rattling Wings and the other Thunder People. Together, they need to make an appearance at the Sundance.” Can you talk about this reconciliation of opposites, the stylized language, and your decision to shoot on a set? Why are they wearing anklets and bracelets?

Dana: It was commissioned to be an online work, where it’s still available to be viewed. (http://www.stormspirits.ca/English/Storm/index.html) I began as a poet, and continue to write a lot of poetry, so a lot of my scripts have that element to them. I have an ongoing interest in Shakespeare and Elizabethan language, as well as everyday conversational language. Both appear in this particular script which overlays and collapses different styles. The proposition is that they’re having a chat while waiting. Instead of standing at a bus stop, they are up in the clouds. Their conversation turns around supernatural beings who are due to arrive, and their support of Aboriginal justice. They’re wearing anklets and bracelets because they’re getting ready to go to the Sun Dance.

The Sun Dance ceremony occurs in the summer, during the full moon. Many Plains cultures participate and other Aboriginal groups do too, nowadays. It’s an annual gathering of relatives, and there are marriages and big feasts. For those who dance and those who come to pray, it’s about having good relations with the supernatural world. Certain things have to happen in order to bring the cosmos together.

Mike: Do you feel that in the presentation of your work, you are being asked to shoulder the burden of representing the Sioux, past and present?

Dana: I am not being asked to do anything from anybody, only myself. Or perhaps on a deeper level, it’s my ancestral responsibility to clear this history up and make a more honest telling of it, while at the same time, un-dehumanize Aboriginal people.

Mike: Have you become, or are there expectations that you will become, a spokesperson?

Dana: Well…I am an artist, although perhaps artists would make good politicians, or at least offer different perspectives. If I was ever called upon to speak on behalf of Lakota people or Aboriginal people, certainly I would have to deeply consider and ponder the context in which I am asked to be a spokesperson. I have spoken at conferences and guest lectures, but always as an artist, a maker of culture, never as an official spokesperson

Mike: Here is the beginning of a question Richard Fung posed Paul Wong many moons ago: “Since the 80s, many artists get into the gallery stem on a “race card” and then they hope to become “just artists.” Can you comment?

Dana: The race card should only be used when someone has called you a bad name, slapped your face and fired you! I would argue that in the 80’s artists were not playing the race card, rather they were dealing the equality card. Race is a complex thing… I am mixed race, yet I am a Lakota woman.