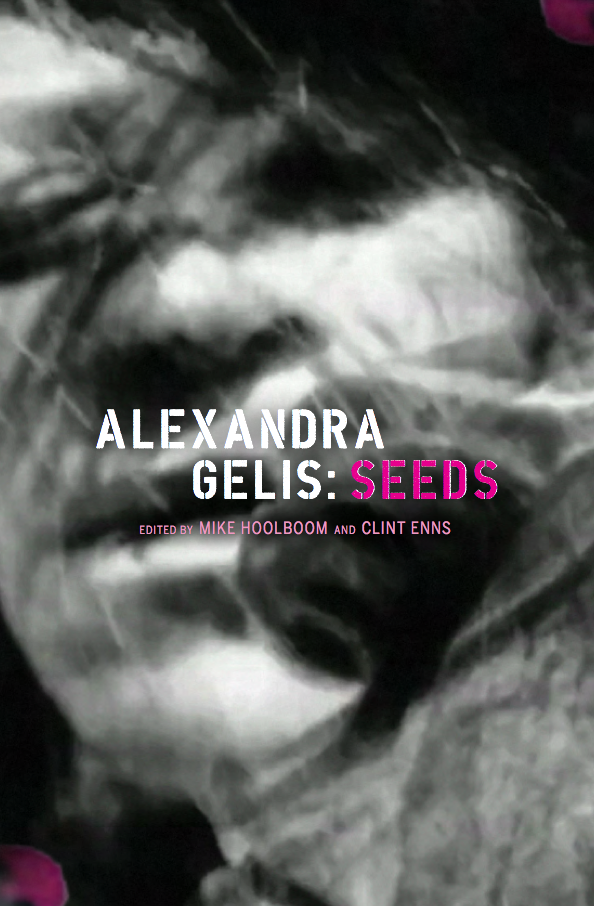

Alexandra Gelis (2021)

Contents

Introduction by Mike Hoolboom and Clint Enns

Introduction by Alexandra Gelis

Movies

English for Beginners by Rebecca Garrett

English for Beginners by Alexandra Gelis

One Dollar Click by Scott Birdwise

One Dollar Click by Alexandra Gelis

La Casa de María/Maria’s House by Dot Tuer

La Casa de María/Maria’s House by Alexandra Gelis

Cooling Reactors by soJin Chun

La Casa de Olga/The House of Olga by Clint Enns

La Casa de Olga/The House of Olga by Alexandra Gelis

Bordes/Borders by Jean Marc Ah-Sen

Conchitas/Conches by Clint Enns

Conchitas/Conches by Jorge Lozano

San Rafael by Mike Hoolboom

San Rafael by Alexandra Gelis

Bridge of the Americas by Cassandra Getty and Dianne Pearce

D-Enunciation by Jorge Lozano

Rhizomatic Directed Simulation by Madi Piller

Rayado en Queer by Christine Lucy Latimer

Kuenta by Jorge Lozano

How to Make a Beach by Jorge Lozano

How to Make a Beach by Francesco Gagliardi

The Island by Richard Fung

Radiotherapy by Mike Hoolboom

Thoughts from Below by Jorge Lozano

Thoughts from Below by Kathryn Michalski

Raíces Fúlcreas / Prop Roots by Kathryn Michalski

Alerta. Alerta. Alerta. by Christine Negus

Alerta. Alerta. Alerta. by Inti Pujol

Entradas y Salidas/Exits and Entries by Tom McSorley

Installations

Casiteros by Mike Hoolboom

Raspao/Snow Cone by Mike Hoolboom

Autorganizaciones: 24h informal economy news by Manuel Zuñiga Muñoz

Raspao, Afectos Descentrados, Personidos by Jorge Lozano

Cosiendo el Bosque/Sewing the Woods by Julieta Maria

Corredor by Kate MacKay

Corredor: The Big Picture by Claudia Arana

Bahareque/Adobe by Clara Inés Guerrero

Weeds/Mala Hierba by Deborah Barndt

Estera/Mat by Paola Camargo González

CERCA-VIVA by Alexandra Gelis

Keeping it Distant from Up Close: How to See Cancer by Carla Gabrí

Ven Acá by Sinara Rozo-Perdomo

Ven Acá by Jorge Lozano

Conversations

Alex’s Legacy in the Legacies Project by Deborah Barndt

Invisible Forces: an interview with Alexandra Gelis by Mike Hoolboom

List of works

Introduction by Mike Hoolboom and Clint Enns

The artist is a nomad. Before the endless treks, her living room overflows with cables, cameras, and recorders which somehow find a place in her oversized luggage. If her open heart leads her to plant roots wherever she travels, her recording gear is never far, absorbing traces of encounters, ideas, stories.

She is attracted to geographical wounds, sites of trauma, where the ghost trails of colonialism are all too evident. Wearing her armour of mini skirt and magenta hair, she facilitates workshops in a gender performance disguise, allowing her to pass, even amongst gang members and street youth. What she hopes to achieve in these workshops is the aim of any artist: to allow everyone to find their own voice and express their own life in their own way. Artworks contain potent seeds that when planted in the right conditions begin to germinate.

Many of Alexandra’s works are made in the spirit of collaboration. In particular, her engagement with fellow traveller Jorge Lozano has been essential. They have been working on each other’s artworks since the mid-2000s, lending footages, cutting side by side, weighing colour corrections and philosophical vantages.

The voice of the undercommons spreads through Alexandra’s movies like a weed. Her single-channel work is marked by portraiture, offering glimpses of the homeless, of queer laundromat philosophers, of home-brewed historians. There are some who cannot forget, and she is there to absorb their feelings, and bring back the evidence. As Viet Thanh Nguyen writes in The Committed,

Americans sincerely believe, as all imperialists do, that they have taken over the world for its own good, as if imperialism were a kind of penicillin (for natives), with power, profit and pleasure merely being surprising side effects (for the doctors).

In Alexandra’s installations, there is a persistent look at how her homelands have been marked by America’s cruel imperialism and by the secrets that only plants can share with us. Hers is an evolving practice, as her tech-geek side meets up with local conditions and materials. One installation morphs into the next in a suite of theme and variations, always with the hope of producing contact and community, face-to-face encounters and, above all, new questions. Who are we, if we are not questions?

This book examines the roots of Alexandra’s rapidly expanding body of work. The individual essays within are micro-studies of the environmental impact that her engagements have had on the fragile ecosystems inhabited by artists, activists, and scholars. As such, the book takes on a rhizomatic structure where none of the individual pieces are intended to provide a complete map of the work it’s responding to.

When read in relation to the rest of the writing, each text provides the reader with different approaches to Alexandra’s ever-evolving artistic practice and with ways to navigate the uncharted regions of the work on their own. These essays, like Alexandra’s work, assert that there is space for the political in the poetic and the poetic in the political, and that, through dialogue, collaboration, and solidarity, we can better understand one another and find ways to recognize and fight systems of oppression.

Introduction by Alexandra Gelis

I have had a nomadic life, in constant migration from one city to another. I have been a woman traveller with a camera in my hands, sometimes into dangerous lands, capturing and reframing humans and non-humans usually absent from the media. At other times I have brought the tools (DIY technologies) and cameras into communities for self-representation workshops or collaborative creation projects.

In my life of constant movement I was “called” by the plants, and became interested in the relationship of plants and people. Plants that supposedly don’t move are the ones that taught me most about the politics behind migration. I started exploring how native, non-native, invasive, and “migrated” plants are connected to the forced and non-forced migration of people and to the colonization of territories. The bio-political presence of plants to control people and territories has been my main concern in the last ten years. My work deals with botanics as a form of resistance: plants that are used as territorial control technologies (TCT), both by those in positions of control and by subaltern resistances to those controls.

Since 2009, I have worked on two main projects. The first project, Corredor, is an ongoing exploration of the elephant grass planted as a living barrier around the Panama Canal by the United States Army during the Vietnam War. It was brought from Vietnam to control the Canal Zone and to keep Panamanians out of U.S. military bases.

The second project, MAT: Medicinal Plants and Resistance, was initiated in San Basilio de Palenque, an Afro-Colombian town, known as the “first free town of the Americas.” I investigate the history of seeds and medicinal and ritual plants that were brought by runaway slaves, often hidden in their hair. Used to reshape the new free territories, these plants are today growing all over patios, land, and sidewalks.

The smells of the fruits of Mrs. María, all my childhood memories with my aunties (my mom’s best friends who were historians, educators, artists, women leaders who shaped the ethno-education law in Colombia and the declaration of San Basilio de Palenque as a UNESCO Heritage site) brought me back to the town in 2011 with an invitation to give a media workshop. To access memories of the plants, I started an art-based collaborative research and creation project working with elders, who had the memories, and with youths, who were no longer interested in traditional knowledge.

We used media technologies as a connection device; cameras became the main tool for intergenerational communication, youths framing the plants with cameras while elders explained the visible and the intangible aspects of the stories of the plants. Over several years we captured hundreds of stories, recording for new generations the images and voices of many abuelos who are no longer with us. Rather than write a book that the youth would not be interested in reading, I created an online platform to gather the complex plant-human narratives, stories told in layers where drums, colours, dance came together, where the storytellers’ ways of moving, their Palenquero language, and their animistic beliefs formed a unit. This project became the base for my doctoral research: “An Arts-Based Inquiry into Plant/human relations in Equinoctial America: A case study of San Basilio de Palenque, Colombia.”