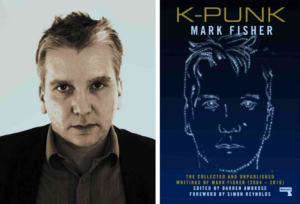

K-punk: The collected and unpublished writings of Mark Fisher

This comprehensive collection brings together the work of acclaimed blogger, writer, political activist and lecturer Mark Fisher (aka k-punk). Covering the period 2004 – 2016, the collection will include some of the best writings from his seminal blog k-punk; a selection of his brilliantly insightful film, television and music reviews; his key writings on politics, activism, precarity, hauntology, mental health and popular modernism for numerous websites and magazines; his final unfinished introduction to his planned work on “Acid Communism”; and a number of important interviews from the last decade. Edited by Darren Ambrose and with a foreword by Simon Reynolds.

Punk fanzines were more important than the music because they allowed and produced a whole other mode of contagious activity that destroyed the need for centralized control.

The development of cheap and readily available sound production software means there is an unprecedented punk infrastructure available. The belief that what happens without authorization or legitimization can be more important than what comes through official channels.

Our deepest desire isn’t to be possessed by someone, but to be objectified by them, to be used by them as their fantasy. The perfect erotic situation isn’t about domination or fusing with each other, it’s about being objectified by someone you want to objectify. Couldn’t you be my thing?

Traditional marriage: each partner contracts out their genitals in exchange for the use of their partner’s.

Treating people as if they were intelligent is elitist.

Treating people as if they were stupid is democratic.

The salvagepunk archive of YouTube.

Tobias van Veen: There is an ironic yet devastating demand being placed on the labourer: while work never ends (as one is never out of touch, and always expected to be available) you as a worker are nonetheless completely expendable, and thus a member of the precariat: this contemporary condition of on-call ontology or on-demand dasein produced an emotional economy of stress. To live under such instant-demand duress is stress-inducing indeed. Life becomes a series of panic attacks in the face of workplace demands which make life impossible to distinguish from work. The managerial class uses techniques of guilt/loyalty to force workers to labour at a moment’s notice, without hope of a raise, without benefits or reward, and all for a minimum wage.

Do you have to lose your voice in order to speak?

Goth: trying to make up for the symbolic deficit, dressing up as re-ritualization, a recovery of the surface of the body as the site of scarification and decoration – a rejection of the idea that the body is merely the container of envelope for interiority.

An energy crisis in culture.

What we have experienced is merely a blip, perhaps never to be again repeated – 150 years of extreme resource binging, the equivalent of an epic amphetamine session. What we are already experiencing is little more than the undoubtedly grim ‘comedown’ of the great deceleration. (Alex Williams, Splintering Bone Ashes blog)

The Sex Pistols and those who followed them did change the world, not by starting a war or a revolution, but by intervening in everyday life. What had seemed natural and eternal – and which now appears to be so again – was suddenly exposed as a tissue of ideological presuppositions. This is a vision of politics as a kind of puncturing, a rupturing of the accepted structure of reality. The puncture would produce a portal – an escape route from the second-nature habits of everyday life into a new labyrinth of associations and connections, where politics would connect with art and theory in unexpected ways. When songs ceased to be entertainment, they could be anything. These punctures felt like abductions.

All music functions either to embed or to disrupt habituated behaviour patterns. Thus, a political music could not be only about communicating a textual message; it would have to be a struggle over the means of perception, fought out in the nervous system.

Dominant music culture has been reclaimed by a Tin Pan Alley populism that once again reduced music to entertainment. The internet and streaming services are part of a new economy of musical consumption in which the possibilities of being abducted are attenuated. In a world of niches, we are enchained by our own consumer preferences. What is lacking is the public space that could surprise or confound our understanding of ourselves.

After the Future.

Jennifer m Silva Coming up Short – working class adulthood in an age of uncertainty

In Britain the 70s was not the hangover after the 60s; it was the point when the great 60s party actually started. The successful Miners’ Strike of 1972 saw an alliance between the striking miners and students that echoed similar convergences in Paris 1968 with the miners using the University of Essex’s Colchester campus as their East Anglian base. The 70s also saw the growth in Britain of gay, anti-racist, feminist and Green movements. In many ways, it was the unprecedented success of the left and the counterculture in the 1970s that forced capital to respond with neoliberalism. This was initially played out in Chile, after Pinochet’s CIA-backed coup had violently overthrown Salvador Allende’s democratic socialist government, transforming the country – via a regime of repression and torture – into the first neoliberal laboratory.

Allende was experimenting with a form of democratic socialism which offered a real alternative both to capitalism and to Stalinism. The military destruction of the Allende regime and the subsequent mass imprisonments and torture are the only the most violent and dramatic example of the lengths capital had to go in order to make itself appear to be the only realistic mode of organizing society. Neoliberalism: financial deregulation, the opening up of the economy to foreign capital, privatization)

Marcuse anticipated the counterculture’s challenge to a world dominated by meaningless labour. The most politically significant figures in literature, he argued in One-Dimensional Man, were those who don’t earn a living, at least not in an ordinary and normal way. Such characters, and the forms of life with which they were associated, would come to the fore in the counterculture. Marcuse worried about the avant-garde’s absorption by capital because he had already seen capitalist culture convert the gangster, the beatnik and the vamp from images of another way of life into freaks or types of the same life.

The refusal of work was also a refusal to internalize the systems of valuation which claimed that one’s existence is validated by paid employment. A refusal to submit to a bourgeois gaze which measured life in terms of success in business.

The mass media helped to spread rebellion, and the system obligingly marketed products that encouraged it, for the simple reason that there was money to be made from rebels who were also consumers. On one level the 60s revolt was an impressive illustration of Lenin’s remark that the capitalist will sell you the rope to hang him with.

*The revolution would fundamentally look at how care and domestic arrangements were organized.

In the 70s, disco was a music that grew out of the convergence of a number of subjugated groups. It was a music made by and for gays, black people and women and- like most postwar popular music, it was overwhelmingly produced by the working class. Chic’s Nile Rodgers – surely the most important producer and sonic conceptualist of the late 70s and early 80s – had been a member of the Black Panthers as a teenager. Disco provided the template for successive waves of dance music in the 80s and 90s, including house, techno, rave and garage.

In her 1991 book Design After Dark, Cynthia Rose wrote about a dance floor revolution that “Come about through grass-roots changes – successive waves of guerrilla sounds, guerrilla design, guerrilla entertainments. The new design dynamic will be an impulse born out of celebration, rising out of leisure enacted as an event. And it will change young people’s perception about what entities like design and communication should do.

Rose understandably failed to anticipate the extent to which the new energies, infrastructures and forms of desire she identified would be appropriated by a neoliberal culture which would lay claim to freedom and pleasure, while associating the left with a grey puritan statism. Once again, the left missed an opportunity, failing to successfully align itself with the collective euphoria of dancefloor culture. Thus the ‘good times’ on the dancefloor became fleeting escapes from a capitalism that was increasingly dominating all areas of life, culture and the psyche.

Christian Marazzi (finance, attention and affect lecture) dated the amount of the switch from Fordism to post-Fordism very precisely: 6 October 1979. It was on that date that the Federal Reserve increased interest rates by 20 points, preparing the way for the ‘supply-side economics’ that would constitute the ‘economic reality’ with which we are now so familiar. The rise in interest rates not only contained inflation, it made possible a new organization of the means of production and distribution. The economy would no longer be organized by reference to production, but from the side of the point of sale. The ‘rigidity’ of the Fordist production line gave way to a new ‘flexibility,’ a word that will send chills of recognition down the spine of every worker today. The flexibility was defined by a deregulation of capital and labour, with the workforce being casualized (with an increasing number of workers employed on a temporary basis) and outsource.

The new conditions both required and emerged from an increased cybernetization of the working environment. The Fordist factory was crudely divided into blue and white collar work, with the different types of labour physically delimited by the structure of the building itself. Labouring in noisy environments, watched over by managers and supervisors, workers had access to language only in their breaks, in the toilet, at the end of the working day, or when they were engaged in sabotage, because communication interrupted production. But in post-Fordism, when the assembly line becomes a ‘flux of information,’ people work by communicating. As Wiener taught, communication and control entail one another.

What Deleuze, after Burroughs and Foucault, called ‘the society of control’ comes into its own in these conditions. Work and life become inseparable. As Christian observed, this is in part because labour is now to some degree linguistic, and it is impossible to leave language in the locker after work. Capital follows you when you dream. Time ceases to be linear, becomes chaotic, punctiform. As production and distribution are restricted, so are nervous systems. To function effectively as a component of ‘just in time production,’ you must develop a capacity to respond to unforeseen events, you must learn to live in conditions of total instability, or precarity. Period of work alternate with periods of unemployment. Typically you find yourself employed in a series of short-term jobs, unable to plan for the future.

The disintegration of stable working patterns was in part driven by the desires of workers – it was they who, quite rightly, did not wish to work in the same factory for 40 years. In many ways, the left has never recovered from being wrong-footed by capital’s mobilization and metabolization of the desire for emancipation from the Fordist routine. Especially in the UK, the traditional representatives of the working class – union and labour leaders – found Fordism rather too congenial; its stability of antagonism gave them a guaranteed role. But this meant that it was easy for the advocates of post-Fordist Capital to present themselves as the opponents of the status quo, bravely resisting an inertial organized labour pointlessly invested in fruitless ideological antagonism which served the ends of union leaders and politicians, but did little to advance the hopes of the class they purportedly represented. And so the stage was set for the neoliberal ‘end of history, the ‘post-ideological’ ideological justification for rampant supply-side economics. Antagonism is not now located externally, in the face-off between class blocs, but internally, in the psychology of the worker, who is interested in the investments of their pension funds. There is no longer an identifiable external enemy. Post-Fordist workers are like the Old Testament Jews after these left the house of slavery in Egypt – liberated from a bondage to which they have no wish to return but also abandoned, stranded in the desert, confused about the way forward.

Disintegration of the old left’s power base because of Post-Fordist restructuring of capitalism: globalization, the displacement of manufacturing by computerization, the casualization of labour, the intensification of consumer culture.

The psychological conflict raging within individuals – they themselves are at war – cannot but have casualties. One hidden, or at least naturalized, consequence of the rise of post-Fordism that the ‘invisible plague’ of psychiatric disorders that has spread, silently and stealthily, since around 1750 (ie. the very onset of industrial capitalism), has reached a new level of acuteness in the last two decades. Many have simply buckled under the terrifyingly unstable conditions of post-Fordism.

Depression was not experienced collectively, but took the form of the decomposition of collectivity in new modes of atomisation. Denied the stable forms of employment that they had been trained to expect, deprived of the solidarity formerly provided by trade unions, workers found themselves forced into competition with one another on an ideological terrain in which such competition was naturalised (because there is no standard, no amount of work will ever make you safe). The imposition of self-surveillance mechanism.

Instead of the elimination of bureaucratic red tape promised by neoliberal ideologues, the combination of new technology and managerialism has massively increased the administrative stress placed on workers, who are now required to be their own auditors. Work, no matter how casual, now routinely entails the performance of meta-work: the completion of log books, the detailing of aims and objectives, the engagement in so-called ‘continuing professional development.’ Systems of permanent and inescapable measurement engender a constant state of anxiety. The market solution generates a huge and costly bureaucracy of accountants, examiners, inspectors, assessors and auditors, all concerned with assuring quality and asserting control that hinder innovation and experiment and lock in high cost. Managerialism were aimed to weaken the power and labour and undermine worker autonomy in order to restore wealth and power to the hyper-privileged/ruling class.

Relentless monitoring is closely linked to precarity. On the one hand, work never ends: the worker is always expected to be available, with no claims to a private life. On the other hand, the precariat are completely expendable. The tendency today is for practically all forms of work to become precarious. As Franco Berardi puts it, “capital no longer recruits people, but buys packets of time, separated from their interchangeable and occasional bearers. These packets of time have no particular connection to people, they are either available or unavailable.

Mental illness is almost never spoken about as a symptom of class warfare, but as chemical and biological disease. Considering mental illness as an individual problem of chemistry and biology has enormous benefits for capitalism. It reinforces capital’s drive toward atomistic individualization (you are sick because of your brain chemistry), and second it creates a new market frontier in brain chemistry for SSRI drugs.

The focus on serotonin deficiency as the cause of depression obscures the social roots of unhappiness, such as competitive individualism and income inequality. Studies show the links between happiness, and political participation and extensive social participation, friends, volunteering. A public response to private distress is rarely considered as a first option. It is clearly easier to prescribe a drug than a wholesale change in the way society is organized. Meanwhile happiness has become another frontier for capitalism, there are a multitude of people offering happiness now in just a few simple steps.

Psychiatry’s pharmacological regime has been central to the privatization of stress. But also: Margaret Thatcher’s view that there’ no such thing as society, only individuals and families, finds an unacknowledged echo in nearly all approaches to therapy. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy combines a focus on early life with the self-help doctrine that individuals can become masters of their own destiny. Psychic entrepeneurealism. Oprah assures us that the fetters on our productive potentials lie within us. If we don’t succeed, it’s simply because we haven’t put the work in to reconstruct ourselves.

The class war is based on the notion of the individual, of individual choice and freedom. The interiority presupposed by much therapy is little more than an ideological special effect. Like Spinoza, David Smail understands that the so-called “inside” is really a folding of the outside. Most of what is supposedly inside us has been acquired from the wider social field. “Many of the characteristics that we tend to regard as entirely “psychological” are acquired from outside. The most significant case in point is probably ‘self-confidence,’ the crumbling of which is so often at the root of the kind of personal distress which is diagnosed by the experts as neurotic.

Smail: What people who suffer psychological distress tend to become aware of is that no matter how much they want to change, no matter how hard they try, no matter what mental gymnastics they put themselves through, their experiences of life stay much the same. This is because there is no such thing as an autonomous individual. What powers we have are acquired from and distributed within our social context, some of them (the most powerful) at unreachable distances from us. The very meaning of our actions is not something that we can decide by ourselves, but is made intelligible, but makes sense only inside cultural frames over which we have virtually no control.

Jennifer M. Silva: In social movements like feminism, self-awareness, or naming one’s problems, was the first step to radical collective awareness. But for today’s generation, it is the only step, completely detached from any kind of solidarity; while they struggle with similar and structurally rooted problems, there is no sense of ‘we.’

The spreading of therapeutic narratives was one way that neoliberalism or the class war, contained and privatized the molecular revolution that consciousness raising brought about. The struggle to dismantle the class war will necessarily involve the rediscovery and reinvention of these formerly popular practices. When can talking about our feelings become once again a political act? When it is part of a practice of consciousness-raising that makes visible the impersonal and intersubjective structures that ideology normally obscures from us.

The privatization of stress has been part of a project that has aimed at an almost total destruction of the concept of the public – the very thing upon which psychic well-being fundamentally depends. What we urgently need is a new politics of mental health organized around the problem of public space.

The increase in bipolar disorder is particularly significant. Capitalism, with its relentless boom and bust cycles, it itself fundamentally bipolar. Capitalism is characterized by a lurching between hyped up mania (the irrational exuberance of bubble thinking) and depressive come-down. The term economic depression is no accident.

Workers find themselves working harder, in deteriorating conditions and worse pay, in order to fund a state bailout of the business elite, while the agents of that elite plot the further destruction of the public services on which workers depend.

Capital is an abstract parasite, an insatiable vampire and zombie-maker, but the living flesh it converts into dead labour is ours, and the zombies is makes are us.

The ultimate goal of ideology: invisibility.