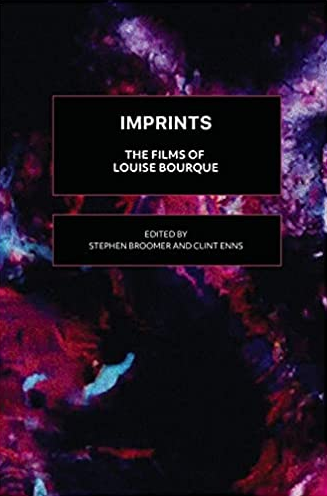

Imprints: The Films of Louise Bourque edited by Stephen Broomer and Clint Enns (2021)

download the PDF

Contents

List of Ephemera

Introduction

Imprints by Stephen Broomer

Impossible Trips Back Home: The Films of Louise Bourque by Michael Sicinski

“It’s dark in the tunnel but I’m heading towards the light…” by Nathan Lee

L’autoportrait et autres ruines: Quelques réflexions sur Self Portrait Post Mortem et AutoPortrait/Self Portrait Post Partum – The Self-Portrait and Other Ruins: Reflections on Self Portrait Post Mortem and Auto Portrait/Self Portrait Post Partum by André Habib

Décrier une sensation/Describing a Sensation by Sébastien Ronceray

Remains by César Ustarroz

Palimpsests /Pentimenti: On Louise Bourque’s a little prayer (H-E-L-P) and Remains by José Sarmiento-Hinojosa

Beyond the Fringe: Louise Bourque by Larissa Fan

The Scene of the Crime: Gothic Poetics in L’eclat du mal/The Bleeding Heart of It by Scott Birdwise

Une bouche, deux fois by Patricia MacGeachy

Just Words by Louise Bourque

Talking Oneself into Being: Louise Bourque’s Just Words by Dorottya Szalay

A Fractured Narrative: Notes on Jolicoeur Touriste by Brian Wilson

Notes sur The Visitation/Notes on The Visitation by Sebastien Roncéray

A Conversation with Louise Bourque by Micah J. Malone

Past//Images::Future//Remains: An Interview with Louise Bourque by Todd Fraser and Clint Enns

Letters from Hell by Mike Hoolboom

La père derrière la caméra: Un voyage à travers l’archive familiale des Bourque/The Father Behind the Camera: A Journey Through the Bourque Family Archive by Guillaume Vallée

Dialogues imaginés: Spectroscopie générationnelle/Imagined Dialogues: Generational Spectroscopy by Louise Bourque + Herménégilde Chiasson

Precious Upheavals: Reflections on Going Back Home by Amanda Dawn Christie

A Few In-Camera Observations about Louise Bourque by Clint Enns

Filmography

Contributors

Letters from Hell by Mike Hoolboom

Why not begin with an admission? Like too many others, I once believed in progress. I was sent to the usual schools, where grades were counted in a steady addition, one could begin only with the first grade before passing onto the second, which was only a preparation for the third, which inevitably made way for the fourth. Each subject was presented like the old colonial maps, as half finished continents that should be drawn and conquered in a steady campaign of attrition. The entire project reeked of progress, an incremental accretion of understanding, even of virtue.

But after school, the dutifully copied diagrams praised by my wise instructors were not able to contend with my playground bullies, the cruel hands that taught me the oldest and unwanted joys of submission. Capital had disciplined us well after all. It was difficult to find pictures for this new state, where every hope of order was crushed by a riot of compulsion. I searched for years, until arriving at last at the brief, hardly there movies of the French-Canadian anti-princess Louise Bourque.

It feels strange to write about her picture ruins, as if I were calling out the most retiring person in the room. These are films that refuse notice. They rush past quickly, and are invariably short, as if concerned about overstaying their welcome. They are tangential somehow, they offer not a look but a glance, a glimpse even, a brief interval of openings. Perhaps the fantasy of speaking directly, or illustrating a point, is not where the rub lies, where the urgency calls. Does it seem strange that a projection vehicle like a movie, which is a machine for conserving time and memory, would shrink from the task of presentation? Perhaps these movies offer a different kind of picture, an alternating current even. Locked together, like conjoined twins, is the need to show and to keep a secret.

When I had reached the end of myself and became resigned to film school, I was met there with a population that had been failed by language. They couldn’t talk at all. Sounds would come from their mouths but they were unrecognizable, even to the speakers. But there still burned within each one the desire to express themselves, and so we had arrived at this discount suburban hideaway, hoping the new tools of sound and pictures would allow us to say what words could never manage. I can imagine Louise as one of their number. She’s spent a lot of time standing at the front of classrooms as it turns out, trying to make her rent, talking the film talk, even though she doesn’t believe that explanations are helpful, or even necessary.

Perhaps in place of an interpretation, one could write about Louise’s films as if words no longer mattered, or at least with the certainty that they will never manage to reveal anything of importance. Words can only point to some distant place where meaning and desire might be located. What a relief!

The artist began to work in 1989, and slowly produced a suite of miniatures drawn from her endless Catholic family. She was the youngest of seven children, the pope lived in the maste bedroom encouraging reproduction even as the artist-in-waiting shrank from her expected roles and duties. Where are the bad boys, the ones who don’t fit in? How can I become an escape artist and slip the knot of unwanted attentions? Speaking of knots: I only want what I don’t want. I can only say yes to what refuses me, erases me, negates every hope and action.

In her work she begins with a ground, with first principles, and her ground is always the material. It’s the feeling in her hands. She touches every frame, she runs them through her fingers, which are filled with what she hopes is loving indifference. The materials are the golden brick road of escape, she works the silvery tissues, processing her footage herself, introducing salts and baths and forbidden chemistries so that these stolen moments, clipped from someone else’s hopes, can live again, resurrected, torn away from their former settings (some critics like to name this “the parent footage” as if every movie was a family scene). How else to speak about yourself, if you [feel you?] don’t exist, than to work on an endless autobiography made of footage that others have created? These stolen pictures have roots in the artist’s life, they might as well be flickering from picture frames on her desktop, in place of family albums or Instagram avatars. And they are likewise coping machines trying to accommodate the family banishments of religious-state capitalism. It is this passage, from the nameless dread of experience to the film materials, that creates her process and methods.

Let’s look at a test case, chosen at random from the artist’s modest body of practice.

A Little Prayer (H-E-L-P) (8 minutes, 2011) is the artist’s 12th film, made 22 years after she set to work. It begins with a quotation from Dante’s Inferno. Standing at the bottom three rings of hell, the pilgrim poet remarks on the sunrise. “Such joy attends your rising that I feel/as grateful to the dark as to the light.” Why this equal gratitude, this infernal equation of light and darkness? Perhaps there are things that can be seen only when they are not visible. Louise begins her own journey with a thanksgiving prayer sent into the darkness, which is her proper home and the subject of this interlude.

Dante’s rhyming scheme draws together “the light” and “troubled sight,” reminding us that sight may be troubled in light or darkness. Surely the poet, having undertaken this infernal journey, is afflicted with “troubled sight.” How to unsee, undo, erase? How to remove the unwanted experiences that live inside this body? How to stop the endless return to these wounds, the compulsive repetitions that are the hallmark of trauma?

The artist opens her movie with thanks. Thank you for this darkness, thank you for hell, and especially for the bottom of hell, for the very worst of all. How could I feel the sweetness in my life, if I hadn’t been able to taste this, live this, become this too?

There are just a few pictures in the movie, and they circulate in a round dance. The first shows a man hanging, though his image is flipped, so he appears upside down. This strange reversal of perspective unhangs him. He might be unfalling from his death, perhaps back into his life. He could be defying gravity, overturning every natural law, because only then would his life become possible. Hell of course is the place where everything is “upside down,” inversion is the rule.

The second picture shows the same man pinned against a target. It’s Harry Houdini, the famous American escape artist and showman. These pictures have been stolen from a newsreel, and flicker into view, offered only in brief glimpses. Houdini’s arms are outstretched, his face slightly raised, as if he were receiving messages from his mother in the clouds. It’s a high contrast picture, so in place of eyes there are dark holes that bleed together to produce a ghoulish face, already dead. His hands are bound to a great wooden wheel that stands behind him. The unseen crowd can only wonder: how can he escape his latest trial?

The third image offers us Houdini drowning, his smeared face a mask of regret and unconsciousness. If only I could remember what I had done. All that is left is the smell of the bodies, the taste of him in my mouth.

The fourth shows the escape artist in chains. Here is the freedom one can achieve only in restraint. I can’t help but admire his need to be tightly bound, to admit the caress of leather and steel in a return to the womb, before wriggling free of that obligation too. He offers a grim outlook, the eyes like holes poked into the doughy haze of a face.

Let’s begin again with this admission: these words are a lie. The Houdini instants are not what the viewer encounters at all. This quartet of pictures appear in single frame flashes, often as afterburns, they are sensed rather than seen impressions. Mostly what we witness are the marks of film processing, which is another way of saying: nothing. I guess this is the darkness that makes the sun possible, the midnights for which the artist is grateful. The emptiness, the abyss, the dark places it is necessary to go to in order to find a picture.

Is it possible to imagine again that one needs to make a journey in order to find a picture? That they are not already here, in profusion, hurtling across my apartment universe in a flood of biblical proportions, threatening to drown our lives, our politics, our social relationships, our attempts at culture? This artist is creating an image of a search, and perhaps it’s no accident that she does so using “old-fashioned” methods, artisanal and hand-made. She kneads the emulsion, applying developer before careful washings. Like all acts of love, her handling leaves its mark, and it is these scars that make her search possible. She names them little prayers. The man who is the object of this search cannot be shown directly. If you met him face to face, he would turn you to stone. So the artist enters into this silver labyrinth armed with metaphor and allegory, she finds his likeness somewhere else, and only then is able to move towards the dangerous and forbidden. In other words: she finds a way to face her unbearable truth.

This quest narrative is not resolved in triumphant discovery, there are no homecomings or arrivals. Instead, the film? is an image of the quest itself, the artist’s yields offer only glimpses of a man who cannot help seeking out his own bondage and subjugation. I am a prisoner of myself. And I need you to look at me. I need to make a show of this subaltern abjection. This is how we come together, this is what we might call love.

“Houdini, Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd. All of them are embodied thinkers of the Capitalocene: their movements and gestures pose the question of the end of sovereignty of the living (human) body in relation to technological systems of production and measurement, from the clock to the Cloud. From Houdini to Youngning, the question remains: what does it mean to be free within capitalism? How can the individual body gain agency in relation to the processes of mechanical production and abstraction?” Paul B. Preciado (‘Voguing on the Roof of Corporate Architecture: RIP Wu Yongning’ in Work, Body, Leisure)

Like Houdini, the couple in this film are refugees from the capitalist-machine body regime, hence Louise’s truck with a medium — film — whose serial sprockets/pictures resemble nothing less than an assembly line of images. She takes this machinic art by the hand, trying to turn it. Fleeing modernity in their broken techno-bodies, stunned by the tidal wave of screen culture prosthetics, the artist’s soft machine cinemas are temporary shelters and arrangements for a fugitive reinvention whose tools can only point the way out of the old world dilemmas, without enabling the journey itself. Or as the film’s title puts it: H-E-L-P.

The man is in chains, he can’t help who he has become, he can’t undo his life, nor can she unlock her criminal fascination. They are trying to create new forms of reproduction, new kinds of coupling outside the codes of what is acceptable, moral, reasonable. They want to make new pictures but these are not yet possible, so they have to live on garbage, on the refused and forgotten, and recycle the needs of others in order to find a language for resistance. It’s only by telling someone else’s story that I can arrive at my own. The escape artist is falling and I am falling with him. Enclosed together in a bio-technocapitalist bondage.

The epigraph places the escape artist in the dark underworld of hell. In Dante’s imagination hell appears as a series of circles that bottoms out in a great icy lake where Judas is forever frozen, a giant mirror reflecting hell back on itself. When the poet pilgrim meets men running a race, or plunged in fire, he catches a glimpse of what they are condemned to do for all eternity. Eno once opined that repetition is a form of change, but here, the fundamental character of hell, the quality that makes hell hellish, is repetition.

Houdini in chains looks over at someone. If his body is trussed and frozen, his eyes are restless, opening to an unseen witness to his struggles. How can you help me if I can’t help myself?