Not Mad with Anger

Not Mad with Anger

Usually when people are sad, they don’t do anything. They just cry over their condition. But when they get angry, they bring about a change. Malcolm X

It’s a curious moment for artist’s movies. How many are still caught in the nostalgic time warp of f-i-l-m, drooling fetishists even as labs decline and projection possibilities dry up, or else lumber on with serious technical deficiencies. In Toronto, one notable showcase added a thundering electrical line buzz to each and every 16mm film offering that dared to have a soundtrack. But hey, it’s f-i-l-m.

So it was with some trepidation that I opened the film book of Rhayne Vermette, she was one of those caught in the spin cycle, nostalgic for good old days she was too young to be part of. But if it had led some of her comrades to the usual formalist dead ends favoured by white artists, she tuned up to a different drummer. In each of her movies I am struck by the intensity of the encounter, the sense of something barely contained, the rage above all. It seems she had returned to film not to celebrate its moody atmospherics, but as a way to express her beautiful anger.

Where should we start?

The opening title of Take My Word (2012) is in German and translates as follows: “The weapons are distributed among the Huns and the slaughter begins.” Who are the huns? Well the artist of course. And the slaughter? That might be the original footage that is being revisited here, or more precisely, a single dissolve between the soft face of the heroine, and a children’s book. The weapon used is the cut, which in 16mm filmmaking is rendered satisfyingly physical by putting the sprocketed plastic strip under a “guillotine” blade and slicing through the emulsion. Here the filmmaker rips apart the original dissolve, eliminating any of its smoothness, any sense that these two realities could be easily joined. The dissolve works to efface difference while Rhayne’s version wreaks vengeance on the very notion. She is the enemy of the smooth and the hidden, she doesn’t want seamless and easygoing. Instead she cracks apart the original film, sentences are broken into word fragments that become a survivor’s poetry, a staggered cut-up.

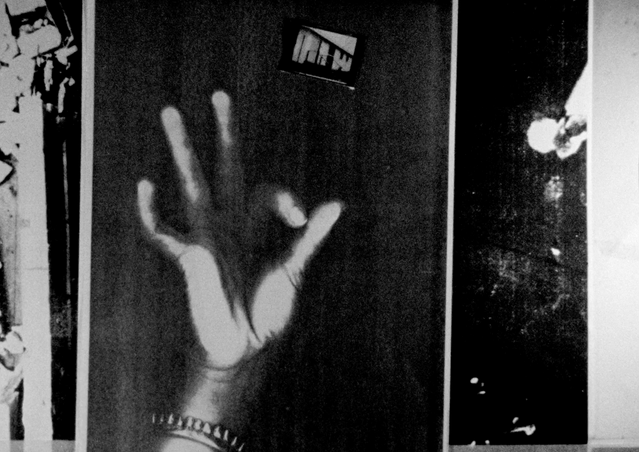

In Tricks are for Kiddo (2:22 minutes 2012) she rips up home movie footage of a young girl dressed as a can-can dancer kicking up her little girl legs. She splices the bits onto clear 16mm leader, then scissors up some 50s dance hall footage, where she finds a barely teenaged crowd looking on with frank sexual interest. She tapes that right onto the clear leader too, jamming it together with the can-can demonstration. This dirt-filled, splice-ridden machine points at the sexualization of young girls (Whose fantasy is already inhabiting her? And how long before she can’t tell where her desire starts and someone else’s begins?). The artist returns to dad’s home movies in order to bring down her anger, summoning a whirlwind of emulsion mutilation. It seems revenge is a dish best served steaming hot.

When I write that the artist, or the artist’s work, is angry, I don’t mean “hysterical”, “overly emotional” or any of the other descriptors men routinely use to frame up and contain female expressions. What I mean is that there are real stakes in the remaking of these pictures. She doesn’t stay at a “copying distance,” or get lost in procedures, or produce exercises. Instead the artist’s body steps into the frame and takes a stand, creates a point of view, articulates a frame, cuts a figure. One notable movie artist assured me, in the afterglow of exactly too many post-screening beers, that the only thing an artist does is to cut a figure. And who does that better than Rhayne Vermette?

In Scene Missing (1 minute 2014) she scratches onto emulsion, transforming the intertitle (the movie’s only image) “Scene Missing” into “See Me Sing.” How else can I sing if I can’t scratch my way into your life? Onto your image? Into your language? And my singing will consist exactly of these scratches, these marks, etched with so much labour and intensity and care. It’s your missing scene, but it’s my doorway. My debut.

She named her 2013 effort Full of Fire (2:13 minutes 2013). How else to read it but as self description? Like all of her work it is incendiary, a quick burn, a short form, filled with ripped up fragments and tortured soundtrack remains. Her source material (her target, the site of demolition and reconstruction) is a fireman newsreel that is slammed together in an unwanted duet with the anxious everywoman from Take My Word.

The pictures are cut up and then spliced back onto the film, scratched and mauled, rubbed and gloriously ruined. The soundtrack begins with a promise that “We’re going to see something absolutely amazing.” And then a 50s girlgang voice-over confides, “You know girls, it’s hard to find a guy who really really… (and here the filmmaker underlines the stutter, forcing her digital avatar to repeat over and over: really really really really…) And the more she repeats it, the more real it becomes, the more apparent it is that behaviours, sexism, mansplaining and patriarchy feature repetitions just like this one. It is the source of immense anger, and anger, at least in the hands of this artist, is a wellspring of creativity and necessary reinvention. Of course it has to be reinvented, because things as they are, are intolerable.

We watch firemen carry their endless hoses while the voiceover recites: “And you just dig everything he does like when he gives you that great big special hug. And that uh, heavy kiss.” What makes a kiss heavy? Hard to bear even? The violence of this fantasy of subjugation (why can’t I be the way he wants, and why do I want it too, even though it’s the very last thing I want?) is present in every splice bar that cuts across the frame, every tape mark and scratch across the image, even the pictures’ dirt-marked and decayed surface. The voice-over recounts a breakup where he just walks away, but she says that he remains as a haunting, an inescapable societal ideology, an enraging prison master. “He was inside of me, in my thoughts, in my dreams, every place I went I saw his face.” Is it the best break up movie of the Canadian fringe?

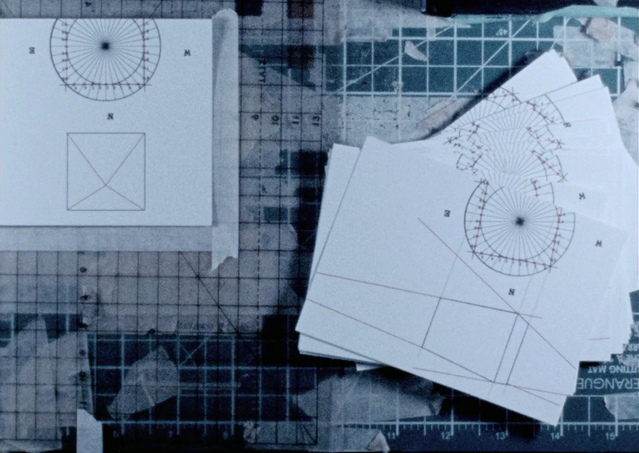

Turin (7:11 minutes 2015) finds the artist in search of a method, a way to take the next step. As usual, this means borrowing from the past, or better: digesting the past, turning the past into some version of your own life, so that it is a living thing, filled with the electrical urgencies of this body in this moment. Curiously or not, the artist’s model turns out to be Italian modernist Carlo Mollino: architect, occultist, racing car driver. “Everything is permissible as long as it is fantastic.”

Fragile and temporary geometries are scratched into black leader, or else conjured in cut up fragments taped back onto film. Voices from the artist’s past sound off on the track, always emphasizing his freedom, his experimentations, his loneliness. These are touchstones perhaps, at the very least they grant permission. The filmmaker writes this curious note about the movie: “Completed in anticipation of a personal pilgrimage to Turin — this film delineates what is at stake for the genius bachelor architect as well as the deplorable, unremittingly heartbroken filmmaker (who adores him so).”

How many times have I seen an artist blaze away in their first few movies, finding a way to attach some brave new tech to deeply felt, barely worded encounters? They can be lucky out of the gate, working with little sense of exhibition histories or expectations, in other words, working as amateurs, “for the love of”, too busy in their immersions to be troubled by the voices that say no. For a few years they might burn bright, and then, inevitably, the work tails off, there is less of it, or somehow it lacks the umph, the urgency and energy, of the earliest efforts. What I see Vermette doing with Turin is making a turn from her first period to the next. Except she does it with no loss or fading away. She finds a new project, a new appetite even, and is able to bring her animation stand pyrotechnics along for the ride, scratching and scraping and taping together the pieces, frame by frame, working furiously, but with a new compass and a new method.

She’s stretching out now, the works can be longer, they don’t have to spend themselves in a single furious exhale, there can be movements, sequences, even moments of pause and reflection. I’m not saying better or worse, there’s no morality here, only that she’s managed to find, to uncover for herself, in her own way, a new possibility, a new practice. For me at least, this turning is a gift. It’s like the first time a friend ever visited Palestine. All of a sudden it was possible, it was part of my world. What else can I say but thanks?