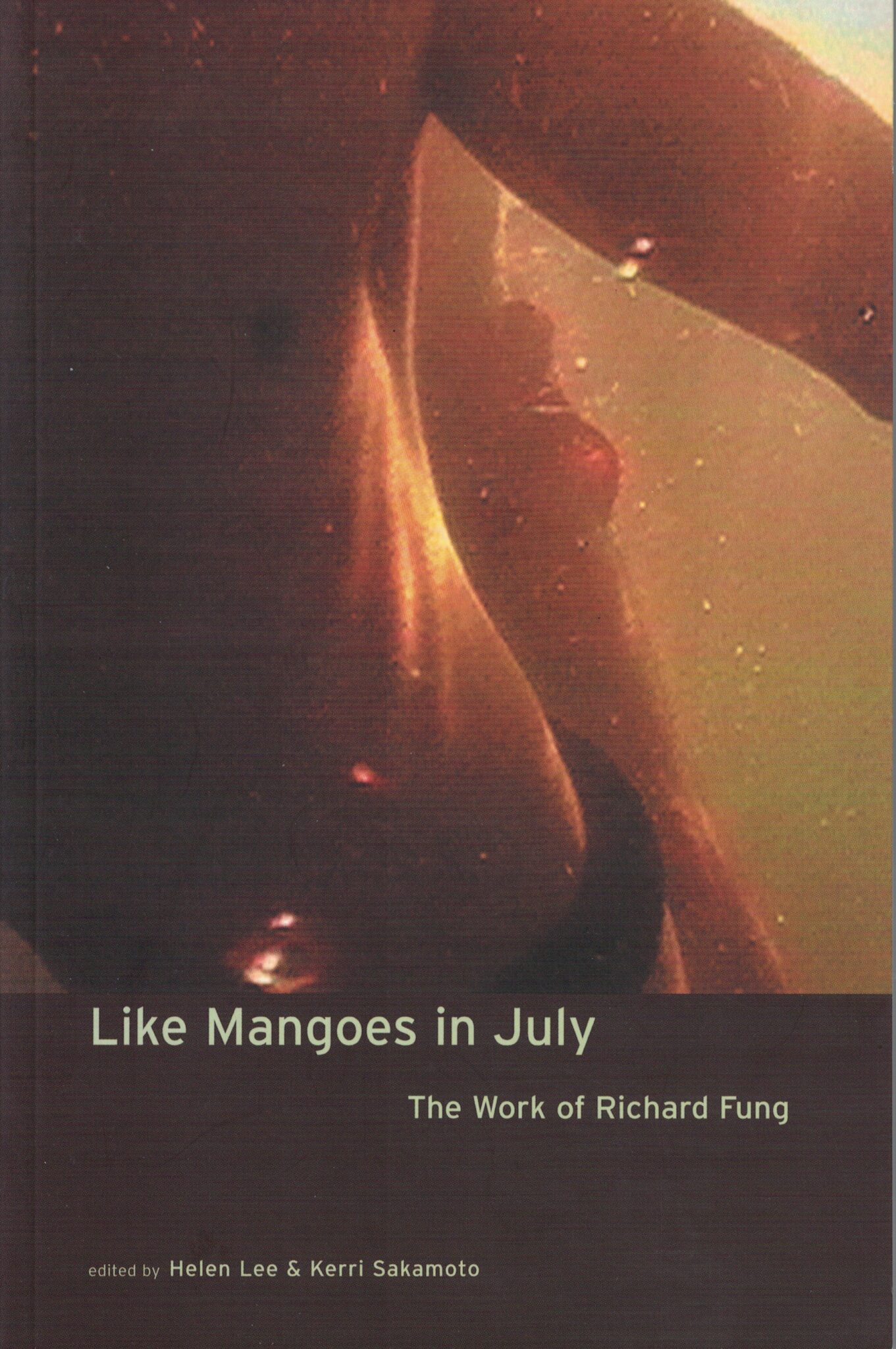

Like Mangoes in July: The Work of Richard Fung edited by Helen Lee and Kerri Sakamoto (2002)

Contents

5 Acknowledgements

8 Introductions

10 The Autobiography of Alice B. Fungus by John Greyson

12 Agency, Activism and Affect in the Lifework of Richard Fung by Monika Kin Gagnon

24 Recalling the Future

26 Into the Light by Kim Tomczak

28 The Way to My Father’s Village by Belinda Edmondson

30 Getting Lost on The Way to My Father’s Village by Peter X Feng

40 Art Link by William Yang

42 Making Meaning by Gabrielle Hezekiah

44 Chinese Characters by Bérénice Reynaud

46 Revisiting the Autoethnographic Performance: Richard Fung’s Theory/Praxis as Queer Performativity by José Esteban Muñoz

58 Take Me to the River by Clive Robertson

60 Untitled by Ming-Yuen S. Ma

62 Knowing Your Place by Elaine H. Kim

64 Steam Clean, Pure Not Prurient by Sara Diamond

66 Fung: Home and Homoscape by Thomas Waugh

78 Break the Frame by Lisa Lowe

80 Still Looking: Negotiating Race, Sex and History in Dirty Laundry by Gina Marchetti

90 The Pecking Order by David L. Eng

92 Callenging the Fiction of an All-White Planet by Wayne Yung

94 A caption for an image of a young man sitting alongside a northern lake, speaking… by Lisa Steele

96 Thoughts on Richard Fung’s “Thinking Through Cultural Appropriation” by Richard William Hill

98 Sea in the Blood by Peter harcousrt

100 What You Don’t Know, But You Know by Fatimah Tobing Rony

102 Undertow by Nayan Shah

104 Dirty Dozen: Playing Twelve Questions with Richard Fung by Helen Lee

116 Stairs by Mike Hoolboom

118 From the Seminal to the Sublime: A Richard Fung Videography by Kyo Maclear

128 Invocations on an image from Sea in the Blood by Patricia R. Zimmermann

130 Walk a Crooked Mile by Kerri Sadamoto

132 Team Sports by Lawrence Chua

134 Publications

138 Distributors

139 Contributors

Introduction by Cameron Bailey

Cilantro.

Richard Fung gives great dinner. I’ve been lucky enough to sit around his table and discover some sparky new Fungian dish. Usually it comes served in a vast, bright communal bowl, and as we take from it, he steers the conversation to whatever new work, or idea, or gossip commands the moment. He’s the perfect host. When Richard and his partner Tim McCaskell throw open their doors, it’s to share good news, to welcome a friend to town to provide a place where people linked by affinity if not by acquaintance can get to know each other.

The metaphor is irresistible. Richard makes videotapes like he hosts dinners. His tapes over the past two decades invite you in, offer new ideas, and new combinations of ideas. They make connections, and they do it all with effortless grace. There is in all of his work—the videotaped, the spoken, and the written—a quality missing from too many works of art: hospitality. It’s in the knowing jokes that bring a panel discussion back to focus, and in the open generosity he brings to even the most personal voiceovers in his Mother/Father/Sister trilogy of tapes, Richard’s work acknowledges, engages and respects his audience.

And yet, there’s the cilantro. A Fung dinner never feels complete without it. In fact, if cilantro didn’t exist, Richard would have had to invent it.

Known as Chinese parsley but born in the Mediterranean. At home in both curries and salsas. An aphrodisiac, from the Han Dynasty to the Arabian Nights. A miracle cure for mercury poisoning. Beautiful and delicate, yes, but with a sharp, difficult scent, a scent that’s especially prickly, apparently, to people of European descent.

Richard has a genius for bringing people together, for making everyone around him want to be as generous, as smart, as funny, and as free from obvious ego as he appears to be. The harmony is dazzling. Hence, the cilantro. There it is: fresh, quivering, coriandrum sativum. A verdant challenge to the otherwise smooth grace of the evening.

Men fuck in Richard’s tapes. They also caress and assert agency. His subjects exceed expectation, including the expectation to be exemplary. Even if that expectation is encouraged by the tape itself.

And Richard himself appears as an increasingly complex subject, both welcoming and provoking, pulling in and pushing away. Even his most personal work, I suspect, guards something private within him. Sea in the Blood admits a degree of internal conflict rare in his work, but it can’t properly be called confessional.

The same dynamic holds in Richard’s lectures and public discussions. He displays a self-deprecating humour that draws listeners in, and a stunning ability to communicate subtleties of argument. At the same time, he allows himself flashes of impatience when the debate fails to meet his high standards. For me it’s this third quality, the cilantro in him, that makes him such a fascinating speaker.

I sometimes divide Richard’s videotapes into those that open questions and those that provide answers. You’ll find lyrical swoons in one tape, and practical pedagogy in the next. But each work itself can be unruly, too. This is the work of an artist/teacher for whom the slash-between-words is a mirror. A broken mirror, perhaps, or an angled one, or maybe frosted. In any case, Richard Fung has set himself the task of living both roles truly.

The essays that follow elucidate, marvelously, the work of Richard Fung. Many find a grand récit that governs his work, or at least governs an understanding of it. That’s the job of essays. But, for me, there is no greater interpretive key to the Fungian oeuvre, than cilantro.