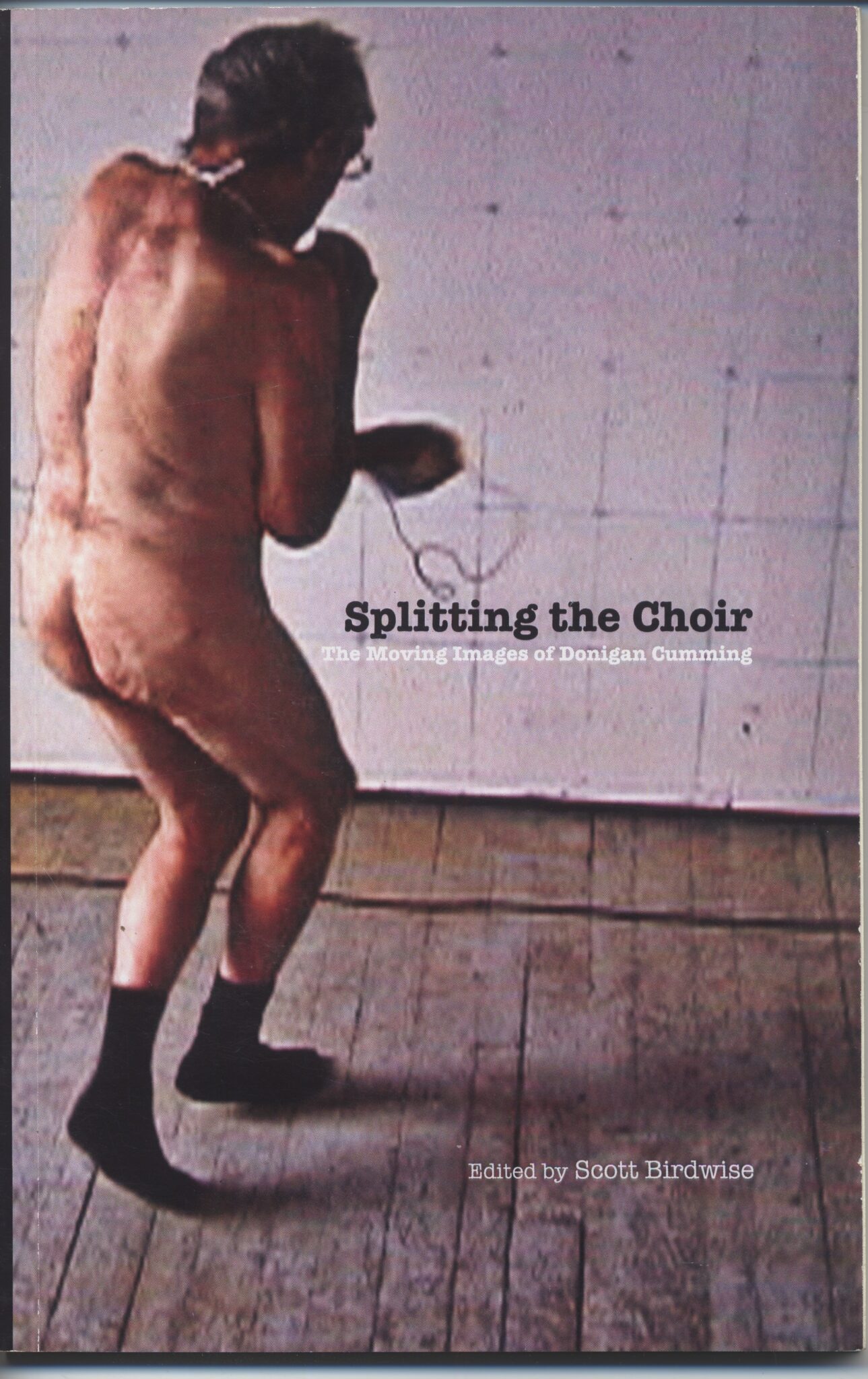

Splitting the Choir: The Moving Images of Donigan Cumming

Edited by Scott Birdwise

Published by Canadian Film Institute, 2011.

An award-winning photographer, videographer and visual artist, Donigan Cumming has internationally exhibited and screened videos that are widely praised (and criticized) for their genre-bending, unsettling iconoclasm. Splitting the Choir – a collection of essays along with a video script, a new interview with the artist and a videography – marks a period of sixteen years since Cumming’s first video, A Prayer for Nettie (1995).

The essays in this volume take up a range of topics in relation to Cumming’s videos, from the role of photography and memory in the moving images and temporalities of video to questions of ethics, representation and performance in the documentary. The essays demonstrate that as Cumming continues to chart the underrepresented life-worlds and experiences of the marginal (elderly, ill, damaged, broken) citizens of Montreal, those who would seem to be so radically “other,” he insistently reminds us of the things we share in common.

Contents

After Beauty by Mike Hoolboom

funeral song by Mireille Bourgeois

Following After Brenda by Tom McSorley

Colin’s Beard by Christopher Rohde

This is Your Life: Donigan Cumming’s Cinematic Antagonisms by Zoë Constantinides

Strange Inventory; or, Cumming’s Masks by Scott Birdwise

Donigan Cumming: Photographs in Video Works by Blake Fitzpatrick

Moments of Photography and The Absoluteness of Loss (Notes on Voice: off) by Solomon Nagler and Craig Rodmore

The Social Life of Things by Marcy Goldberg

Wrap by Donigan Cumming

Territorial Anxieties: An Interview with Donigan Cumming

Videography

Contributors

After Beauty by Mike Hoolboom

Steve Reinke had tipped me to Donigan’s existence, like a detective in a foreign country pointing out one of the locals with a nod of his fedora. That one, he might not look like much, but he’s one of us. Not that Steve would ever be so crass as to speak in the third person. But I was already primed when they rolled out the easy chairs. Where was my Donigan virginity lost? I had dutifully ignored his decades of outsider photography and stepped up only for his opening video memorial work A Prayer For Nettie (1995). As soon as it started, with its harsh lighting and sub-optimal camera microphone sound, and most of all the infuriating tendency of the director to hand hold everything in a wobbly, amateurish paroxysm of anti-spectacle, I closed my heart. No please, not in my avant living room. His subjects — uniformly poor and disheveled and alcoholic — seemed like furniture props for the director’s slumming projects. Oh yes, I used to raise a glass of cheer with you, but now I’m on the way up, and you are the necessary ladder rungs to take me there. Don’t mind my camera boot heel in your face. And don’t think you’re going to be memorialized or anything. What do I look like — Walker Evans? Dorothea Lange? Everything they touched was silver happiness, they could stand their subjects up in front of the worst day of their lives and make it glitter with the kind of truth that makes collectors reach for the deep folded green. But Donigan? It’s as if he’d never heard of silver, and so his subjects — already worn by years of living on the Titanic, still running the self immolation derby that began before the beginnings of memory — looked like they were trying on a last testament, one final pit stop before saying yes to the death drive. Their surgical scars appeared unadorned in the harsh, digital video contrast, their wattled skin like the camouflage of jungle fowl trying to escape notice, their sinking flesh long ago surrendered in a losing fight with gravity.

I was waiting for beauty — even of the abject sort dished up by edge dwellers like Witkin or social justice photographers — who illuminated the overlooked and unwanted in a silvery skin. In other words, I was looking for a shield, for something I could put between myself and the subjects of this work. Surely there must be some kind of consolation (the mastery of tones, the perfect composition, the uncanny intersection of emotive gestures frozen in an instant of narrative collision). Donigan refuses all this. Instead, he pushes his low-fidelity camera into the vanishing faces of his company, mercilessly and without adornment, or even the traditional cinematic easements of triple take grammars and reaction shots. If he was a boxer he would be a slugger, loading up the same punch round after round. Take this, and this and this. When Cocteau quipped that in the cinema we are watching death at work, he might have been describing these encounters.

How helpful for the artist to present to me with the unwanted gift of my own looking, my own point of view. Without the balm of traditional virtues, and all that virtue manages to keep secret, I am confronted by my own wishes and need to look away. My taste. Judgment means what am I willing to swallow, and Donigan serves up dish after dish, until I need to reconsider again the words Freud laid down in an essay he named Negation.

“The judgment is, ‘I should like to eat this,’ or ‘I should like to spit it out’; and, put more generally: ‘I should like to take this into myself and to keep that out.’ That is to say, ‘It shall be inside me’ or ‘it shall be outside me’… the original pleasure-ego wants to introject into itself everything that is good and to eject from itself everything that is bad. What is bad, what is alien to the ego and what is external are, to begin with, identical.”

How can I know who I am unless I can start spitting things out of my mouth, and deciding every time I do: not me, not me, not me, until at last a vague outline takes shape. I would be nothing without my dislikes, my familiar prejudices, my reliable oppositions. National identities, of course, are founded and founder on exactly the same lines. What is a newspaper but the sound of nations spitting each other out?

The Donigan movie that turned the corner for me was Karaoke (3 minutes 1998). The camera draws a bead on its subject, bedridden Nelson Coombs, who appears to have mastered the final posture in every yoga setting, savasana or corpse pose. There’s a folk song playing, a home brewed cover version sung out by Nelson’s girlfriend’s friend, and then accompanied by unseen singers in the room. A wobbly pan runs down the remains of his body, and then the whole thing plays backwards, as if Nelson were a living palindrome. I have a weakness for palindromes, ever since Owen Land worried them in movies like No Sir, Orison (1975) or Wide Angle Saxon (1975), figuring them as necessary preconditions for the conversion experience he held out as the hope of every avant seeing. While I shuddered at Donigan’s make shift pan, longing instead for some dolly tracked, steady as she goes framing, there is an undeniable power in this seeing, and just as Mr. Land might have hoped, my conversion into a Donigan acolyte had begun. The punchline in Karaoke’s single shot encounter arrives in the middle of the tape — exactly where one might expect to see it, given its symmetrical construction. The crux is in the fold, the crease, after which the tape backs right up and does it all again. What is revealed in this moment? Nelson’s toes! Nelson’s toes are moving! Until then the body appears dead, and the insistent closeness of the camera implies some terrible intimacy between viewer and viewed, some prior relation which has brought this anguished proximity to bear. It’s as if the camera wanted to plunge into this body and see every organ and protein redistribution centre and bone marrow replenishment. It just can’t get close enough to register the fact of the death of this strange familiar. But then I see those toes moving, signaling not only life, but some form of pleasure, a pleasure so large and strange and unworldly that even the dead are compelled to tap their toes to this Inuktitut cover song.

My taste and the experiences that I spit out of my mouth (that’s not me!) had been reborn along with Mr. Coombs. Somehow the artist had managed to broaden my acceptable experience, what I could imagine as myself, or for myself (as if I was always up for election, and every object in the world was voting: this is for me, this is not for me). It is the toes of Nelson Coombs that provide the turn. The mirror fold of the movie occurs at the end of his body, at the bottom of it all, the base in every sense of the word, that is mostly kept under wraps. Locked up in a clinch with this nearly dead and supine body, starved and scarred and hardly there, I learn something new about the pleasures of the flesh. Even until the last breath there is the possibility of celebration, of dancing, even carrying the tune. There’s no future and it doesn’t matter.

I met Donigan at last at the closing dinner of the Nyon Festival in Switzerland, a staff-only love-in for its charismatic director Jean Perret. Each of the special guests — as we were described — was asked to do something for the occasion, and while my own contribution is lost even to memory, Donigan engaged Jean in a short skit that involved the A fest director sitting up on his chair and barking like a dog. It was charming and cruel and hilarious at the same time, the loving trust between the two of them palpable. I resolved to look deeper into Donigan’s work.

The next year in Nyon he presented Fountain (22 minutes 2005), a movie premised on his book Lying Quiet (2004) which presents a sequence of video stills. His strategy in producing the book was to take his 143 hours of raw footage and divide it by the number of stills required for the book, approximately 500, which gave him a figure of 17 minutes and 7 seconds. At this point in every tape he would stop and create a frame grab, allowing a second on either side for closed eyelids or pan blurs. These were then intuitively arranged into a final selection of 119 pictures. Using the book as a kind of script, Fountain revisits his work, producing a kind of greatest hits, a quickly paced theme song of despair and decay, not ‘over the top,’ but under the bottom. The faces of the underclass loom into the lens in these up close and personal encounters, whether it is the man who wants to put bars near the toilet to help his father (though it is Donigan who knows that the problem is a broken shoulder, not a broken arm), or the salivating ungrand dame on the oxygen tank, the Elvis send up, the stuttering actor, the toothless display, the home sewn pants, the corner of an uneaten sandwich. Fountain is an accumulation of details that graze across its rooming house interiors, each one a punctum, a piercing point that plunges into the thick and gristle of these usually forgotten and unpictured lives. Like the paper airplane that reads Jesus is my Pilot. Interspersed between the extracts is Donigan’s voice directing his charge, urging them on, reading them letters, asking about their legal status, their health, their parents. He is with them and not with them, holding the camera but refusing to vanish behind it. Instead, he stays in the room with them because the only way to bear witness is as an active participant. Death is never far from his lens. There are hospital visits and memorial photos and sleepers who look like they may never see another morning. Donigan’s engagements throw him into the damage of these difficult lives, and refuses to put ‘them’ over there, on the other side. He doesn’t spit them out. His subjects are a part of him and apart from him, in frame after frame he negotiates this distance, which is the magic of his work as an artist, to find the necessary distance between his life and the lives of those around him.

At last we sat to talk in the shadow of foreign mountains, and he was blunt and smart and didn’t come with an off switch. There was something soft in his face that the rest of him nearly regretted. It was clear he’d been hurt, cut hard and deep and often, and instead of bearing off his wounds in silence and re-encoding them in the catastrophe of family genetics or substance sprees he’d decided to wear them up on his face where everyone could see it. Donigan has a face that hasn’t learned the knack of looking away, in fact, when the usual electric pulse signals flight he seems to draw closer. His world, his ethics and art, all happen in close-up, as he casts his wound of attention into mine, trolling for secrets, and then abruptly pulling away, retiring back into his emotional force field of WASP reserve, near and far, fort und da, back and forth, until it’s time to say good-bye.

“Fountain squeezes the storytelling out of my work. Storytelling has run its course. We are overwhelmed with stories whose seductive plots and strong emotions camouflage the dangerous state of human relations. In Fountain, short fragments of image and sound are intended to subvert the cinematic effect of reality which makes fools of us all.”