Two Worlds: an interview with Mark Cira (2023)

Mike: Armie (2018) is a short one-person psychodrama, featuring a young woman lost in a dream of her haunted past. Her surroundings, whether it’s the abandoned cars in the desert, or surging forests, echo her state of mind. You double-down on her subjectivity by introducing flashes of abstract, hand-processed 16mm footage and fantastically coloured outer space moments, and use a variety of lenses and locations, all delivered in a kinetic, agitated shooting style.

Mark: I was working with a client on Wattpad, an online literary hub for writers. I knew someone there who had worked with me on a CBC project. They had a selection of stories and poems they wanted to adapt for short films. Lysis was a poem Wendii McIver wrote when she was fifteen, one of the most widely read poems on the platform. I had just met Adam Stewart who was my DOP on a Nike spot. This was a perfect opportunity for us to intersect again. We wanted to get to the heart of that story and had a lot of conversations with Wendii about her state of mind when she was writing. It’s an interior psycho-geography when you’re coming into maturation. You carry that angst for the rest of your life but learn to suppress it.

Mike: It looks like you shot this five minute film all over the world.

Mark: Adam gave me his Bolex and some rolls of film and I visited Mount Hood, one of the highest elevation points in America. The poem was written at the same age when I first learned to use this kind of camera. Now I was learning it again. Most of it was shot in Los Angeles, then in Toronto and North Ontario with Adam.

Mike: Where did you find the abandoned cars in the desert?

Mark: I convinced a producer to work for no money. I told him I needed a place that was reminiscent of the end of the world, not Repo Man but Mad Max. He found an area three hours outside of LA called the Salton Sea. I asked him, “Do we have enough budget for gas?” I’d actually done a photography exhibition based on my experiences there. It was a small resort town with a beach but the water dried up and then the money left. Now it’s a ghost town.

Mike: You went to great lengths for shots that last just a few seconds.

Mark: When the Wattpad people saw the film they didn’t know what to make of it. Wendii loved it, but she’s a creative.

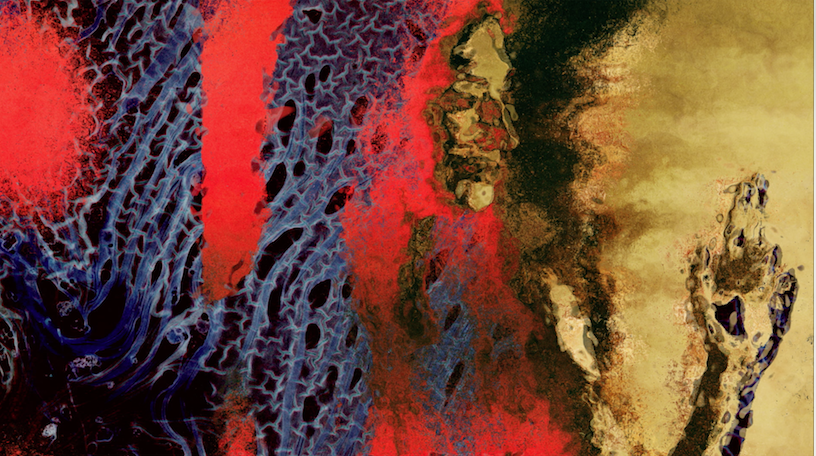

Mike: Lysis (2022) is another wordless short, a fever dream where bodies and cityscapes continually dissolve (“Lysis” is a Greek word meaning dissolving, loosening, setting free). It feels like a love story told from the point of view of the intestines.

Mark: Fellini spoke a lot about falling in love with your past. Nostalgia was labelled a disease when the term was coined. I loved Toronto when I was a kid, but what is a city? A city is a test project for post-industrialization, designed to capitalize on productivity. You fall in love with certain people, and sometimes you pull yourself apart trying to maintain those justifications. When you look back, are the justifications still sound?

Mike: Lysis shows a couple meeting up, hanging out. Why those two, what’s their journey?

Mark: I’d worked with Mila on a short and wanted her look. Josh Obra. I’d found some expired still film and wanted to make portraits. I liked his energy, he’s my cipher in the film. The first image you see is through the windows of a house, a rural setting that melts into the city. We see Josh on a streetcar because I love the old streetcars. I was working for Stephen Low on his IMAX documentary The Trolley. He would tell me all about the history of the streetcar, how they were part of the language of the city. It follows the theme of falling in love with the past, and perhaps you should, it might have parcels of wisdom we overlook. The streetcar is a vessel to reframe the city. Josh is introduced on a streetcar, and later the couple ride together. Is it a memory? At the end we see an elderly man, a photographer named Howard Levant, I interviewed on a cross-Canada train. That was another portrait project, shooting people using certain kinds of transportation. He’s the man who melts into the maze at the end. Perhaps he’s looking back into his past.

Mike: Your cipher Josh shapeshifts into other forms like office towers, but also other people, like the older white man you met on the train. The couple in the film are carried on vehicles that travel both through space and time. Can you talk about the film’s central image of the labyrinth?

Mark: There is something beautiful about being lost in your own mind, wondering where I belong. Why was Picasso so obsessed with minotaurs? In the maze you’re limited to one path. There’s something perversely comforting about knowing that. We like to think there are a million paths, but perhaps that’s an illusion. Maybe there’s just one path.

Mike: It looks like you shot on film, then made copies of the footage and subjected them to various chemical and computer treatments, before weaving all the strands together.

Mark: Adam pushed for experimentation, boiling the film like we did in Armie. I wasn’t sure, “It’s going into Brakhage territory, but alright let’s do it.” Adam put 16mm film into chile or soup. He wanted the acidity of the water to break down the emulsion. I took home these melted, stinking film strips and hung them to dry. Adam did the scanning himself. He got me to fall in love with the medium again and gave me insight into new material possibilities. Working with the physical material was less frustrating than doing digital work, which was a nightmare. I wanted the images to melt into each other, that’s why it took so long. The best parts are when you see the analog and digital degradations together.

Mike: It’s an unusual combination. Usually film geeks stake turf by talking about handmade values and the good old days, while digital wizards draw lines around their corner that aim to look like the future.

Mark: It’s funny how mediums can create tribes. That’s what Lysis is about—the divisions between thoughts and minds, bodies and architectures.

Mike: You mentioned you shot film as a teenager. How did that happen?

Mark: My grandmother liked to shoot 8mm, super 8, 16mm. I remember being nine shooting with her old Minolta. Part of me doesn’t want to fall in love with that time, attaching romantic ideas to it. I tried to go to film school but found it hard. Schools expunge creativity and experimentation, it’s a shame people pay so much for it. What’s coming out of North American schools can often be rote, straight-to-TV work. It’s often catering and pandering. Isn’t that what the professional world is for?

Mike: You’re part of a media org called The Young Astronauts. It was started by Tyler Savery and Nev Todorovic who happened to sit together at a TMU (then Ryerson) orientation session in 2006. A year later, inspired by Napster and Facebook, they started a company that blew up. Their YouTube vids have more than a billion views. One of their showstoppers was a “meme generator” for Drake that invited fans to copy/paste Drake pics into their own pics. Can you talk about how you got involved and what you do?

Mark: In high school we were invited to make a project about whatever we loved. I’m Sicilian-Canadian, a classic film bro at 14 who admired Scorsese. I was put in a group with my close friend Andrew D’Amato and Nev Todorovic who had just arrived at our high school. We got along really well and made a short film together that totally shifted her gears. We had an instant creative chemistry. When we met up again she had her own company and we started collaborating. She lives in Los Angeles now, that’s why I’m here.

Mike: What does working together mean?

Mark: A multitude of things: writing spots, colour treatment for a video shot in the canyons of LA. Right now, Nev and I are writing a coming-of-age script about her strict Serbian immigrant parents and her coming out as a queer person.

Mike: The Young Astronauts make TV commercials for Schitt’s Creek, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and so much more. You’ve been written up in Time Magazine and Rolling Stone. What is the connection between your glamorous corporate life and the short artist movies you’re making?

Mark: There’s a world of difference, though there are overlaps. For example, Neve got a client from Nike to do that campaign, and asked if we should make it in 16mm. I contacted my friend Noah who told me Adam Stewart was the guy. He’s become my longtime experimental collaborator, but it wouldn’t have happened if we didn’t get the budget for that Nike commercial. When Ricky Gervais was asked how he wrote The Office—I’m not comparing myself to Ricky Gervais—he said working in the humdrum corporate world made it possible. I’m not saying it’s an oppressive state but it is moreso film by committee. I’m reluctant to use the word “film.” The experimental stuff of yesterday becomes the corporate language of today. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen Terence Malick or Stan Brakhage applied to car spots. We should open up this Tim Horton’s commercial with… Let’s shoot nature with natural light and wide angle lens flares. That’s where I see the overlap happening. Experimental cinema will become the corporate language of a sports team.

Mike: The Astronauts work requires maximum public impact, though that’s isn’t true for your personal work. Does that divide trouble you?

Mark: That’s a good question. What’s your sign?

Mike: Leo.

Mark: Leos are smart. Kubrick, Hitchcock, Gus Van Sant. They’re in deep. The bread and butter of good marketing is: how many eyeballs can we hijack? I remember being in a colour session for a music video with a producer. He said, “It looks beautiful.” I asked, “What if it was ugly? What if we remade it so you couldn’t even see the talent you paid hundreds of thousands of dollars for?” The impetus for Armie was: what if every image makes you feel uncomfortable? The contrarian part of me wants less and less people to like my stuff. I’d love it if someone said: that’s awful and disgusting. It’s harder now because the threshold for ugly is growing.