48 by Susana de Sousa Dias 93 minutes 2010

The filmmaker doesn’t show us the way her subjects look today, but the way they appeared at the moment of their detention, these political prisoners of the Portugese imperial regime. So in place of a face lined with its terrifying memory marks, there are photographs, floating up out of the darkness, staring back relentlessly, pouring words out of their asymmetries, reflecting on their time inside. They grew old there, the ones that didn’t die.

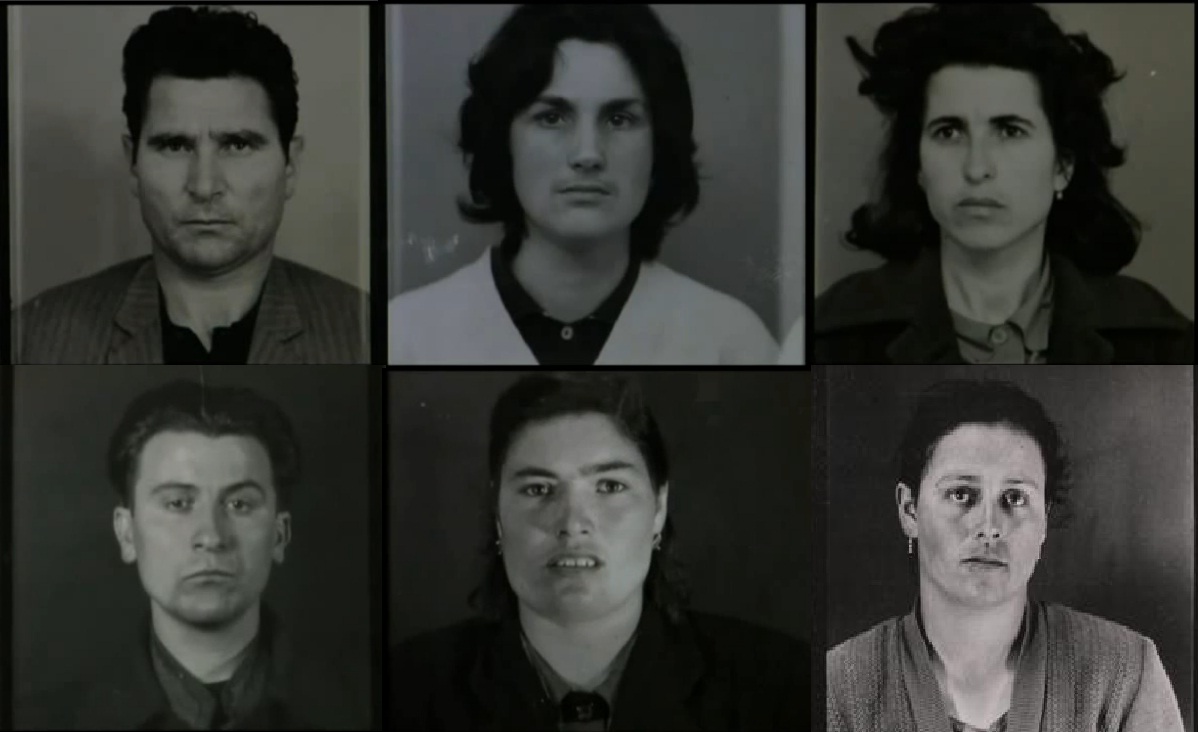

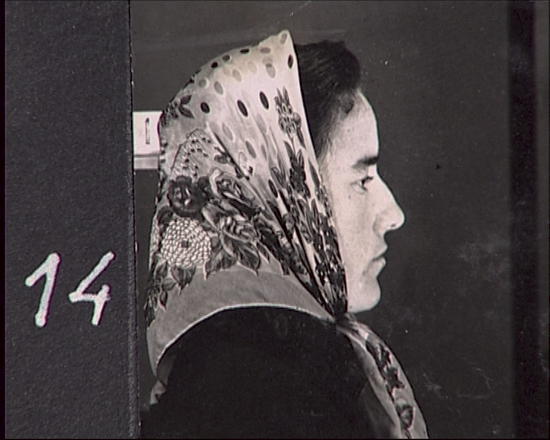

The pictures show their subjects in profile and from the front. They are state pictures, taken by the dreaded PIDE (political police). Part of an official record of repression. All taken during the 48 years of Salazar’s dictatorship, from 1926-1974.

“I ended up living for everybody else,” the first photographed woman tells the filmmaker, her breath and pauses and swallows as much a part of her diction as any testimonial aside. Her photographs hardly able to bear the light of looking. Not after all those years in detention. Another says, “From me, they did not get the pleasure of seeing a tortured face.” There is no hint of triumph in his voice, no sense that there is even the possibility of victory left. But there remains something in him untouched and unmoved by his years of abuse, and I can’t imagine it, he speaks from the other side of the world. How much of his feeling he must have had to shut away in order to maintain this small hope for himself, what kind of effort to maintain the vigil of his dignity. The possibility that this dictatorship would not take root everywhere in his body, that some part of him would resist, some small spark, and from that spark, one day, the entire government would crumble. And it did. Though they were arrested by the thousands, night after night. “After eighteen days of not sleeping, how can a heart keep beating?” one asks, but it does. It survives, even when he has been carried too far. One of them finds a moment of their own empowerment even in the act of having his picture taken, “The face is what you decide.” And of course not providing information to the police. Outside prison, it was difficult to keep state repressions out of everyday conversations, there were things that could and couldn’t be said, and worn and looked at. And sexually, as one former inmate describes, “It’s as if we had no hands.” The body and the body politic. The liberation, the way out, to defeat a regime where there were no longer children (“We were all old, we were all the same age, wearing the same clothes”) it was necessary to begin with each sentence, with each encounter, with the testimonies on offer here, for instance.

Susana de Sousa Dias on her short film Still Life (2005): During the last years my work has been focusing mainly on the subject of the Portuguese New State (Estado Novo), the dictatorial regime established in Portugal in 1933 and defeated abruptly in April 1974 with the Revolution of the Carnations. During my research I have consulted many archives and seen thousands of images. One of the most impressive sensations was, without a doubt, on entering the archives of the former Political Police (PIDE). There I began a thorough investigation: consulting files, studying iconographic material, reading about instructions and methods of PIDE. The defining experience, however, came with the opening of the albums containing the pictures of the political prisoners. The more I looked through the pictures, the more I tried to dig deeper. Then the sensation struck me that in these pictures something unspeakable was hidden, something that could not be explained.

Still Life emerged out of the wish to reflect upon those images apparently the same as all those of the hundreds of thousands of political prisoners ever held in captivity worldwide. Such images led me onto other images from the same period. All of them were the result of a certain form of power being wielded: newsreels, war reports, documentaries made for the Ministry of Propaganda in addition to material that never made the final cut, archive images, mainly in black and white. They all contribute to a vast spectrum of visual documentation revealing this period as never before.