Ascent to the Sky by Stephane Breton 52 minutes 2010

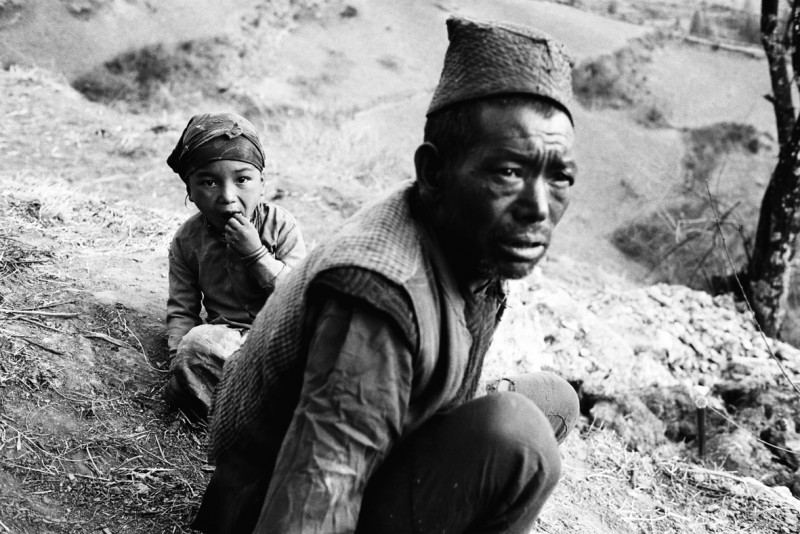

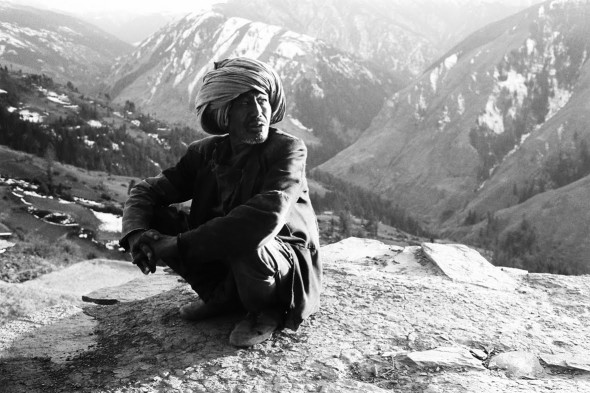

Anthropologist Breton arrives in Nepal, though he insists, “I don’t pick a place, I end up there.” He shows us a man with a fantastical hat shoveling dirt. This is what it feels like, the heft of the earth, newly sodden with rain that continues to fall. The farmer is outside anyway, working, always working. Herding his goats and sheep. Together with friends, he is building a fence, a corral for the animals. His wife digs up the ground behind him, stooped every moment. In the mountains of central Nepal lies the rural village in Nuwakot, a place which is neither emblematic or part of some larger paradigm. The filmmaker does not try to set an example, to present an exemplary case. “I do everything alone, it’s just myself being with them,” Breton says. “Since I am an anthropologist to begin with, being there is what my job is all about.” Oh wait, the neighbours are arguing. The fence builders are crossing the property line. “We used to be rich too. We used to have lots of food.” They argue about shit, about who shits where exactly and who is spreading that shit. The filmmaker stands back, lensing it in mostly wide shots. Except when the men stand by the fence, their old lined faces covered in flies they don’t bother to brush away. Every action is done by hand, and the simple tools – a bit of rope, a shovel, a trowel – is all that they have to help them. In the dust behind each of these houses, as the diligent teen bushes his teeth, the men argue about how much land each has, should have, used to have, will have in the future.

Each frame is an enclosure, a way of penning in these people, of corralling them inside a picture. And yet there is the sense that the filmmaker is letting the rhythms of this small rainy faraway place dictate his own position. He is not there to assert himself, to drive home a point. Instead, he hopes to present, to offer glimpses of what is unfolding in front of him. Cooking flatbread or waiting with the dogs, gathering firewood, planting a row. He’s not waiting for anything in particular, he’s just waiting, and he doesn’t get his subjects to repeat themselves so he can get a better angle or thrill us with triple takes and match cuts that power the new fictional documentaries. Rain is never far. And covering up from the rain. Pitching the tent, pulling the tarp, setting the fire. There is a universe in these hands, this face. Can we slow down enough to see them, find the necessity of this science fiction so that we learn the attention necessary to see our own lustered busyness?