Talk delivered at Centre of Gravity, April 2012. www.centreofgravity.org

Palace

So this is how the story goes, I’m sure you’ve heard it before, I’m sure you’ll hear it again. 25 centuries ago, 500 years before the common era, there’s a prince living in an Indian castle. Everything he wants, everything he ever imagined is there, in his castle. Have you ever had days like this? I just read about them in books. Yes, it’s a small and perfect life, that’s the thing about perfect, you could say it’s the price of being perfect. The price of being perfect is being small, all of my short friends assure me tall people will never be perfect. In order to hold that combination of parts in excellent balance – or is it an excellent imbalance? – you need something small, it should be contained. So there’s this prince living in a small and contained world, no sooner does he say the words “I want,” then it appears somewhere around him. Is this.. happiness? I don’t know but I’d be willing to give it a try.

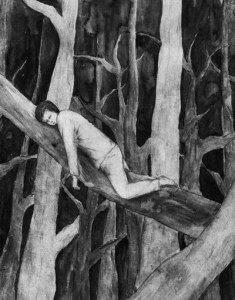

But perfect only goes so far it seems, and when he gets tired of getting what he wants, could we put it that way, could you put it that way, have you ever become tired of getting what you want, willing at last to trade the familiar disappointments and heartbreaks for, well, something else, perhaps we could call it: getting what you didn’t know you could possibly want.

What he wanted first of all was a peek beyond the walls, so he leaves the palace. He asks a charioteer hey, hey, can you take me outside? What is all that, who is all that, out there, anyways? And he encounters on this forbidden trek, this pilgrimage into the unknown, beyond the container, beyond anything that is familiar he sees an old man. Can you remember yourself, the first time you might have ever seen an old man? What does it mean: to see someone who is old? For a child, everyone is old, or at least older. But so many children don’t base their personality preferences on age, have you noticed that? Unlike adults, even teenagers, oh, you’re not my age, I can’t talk to you. We can’t hang out. Friends? Forget about it. The act of seeing someone who is old for the first time, I’ve really been wondering how it’s possible. And perhaps it becomes possible when you yourself are seen, by that old person, as that old person, as that aging person. When you experience that hitch, that hiccup, that glitch, when the smooth stream of it all. Oh, wait, it happens in one moment, before that moment there is a smooth stream, you’re “sailing along” as they say, just another person trying to prove that youth is wasted on the young, and then something happens that causes a glitch. Oh. And all of a sudden you’re an old woman, looking back at yourself. All of a sudden what was timeless, out of time, not even forever young, just forever, that horizon of time shrinks down and… Is that a wrinkle on my face. My perfect endlessly youthful face. Oh god I’m dying. My face keeps talking to me and it’s saying: Oh god, you’re dying, I have the proof right here, on the right cheek. Don’t try to turn it, it’s no use. This my friend, is the beginning of the end.

The second of the prince’s four sights is a sick man. Can you remember the first time you ever saw a sick person? Susan Sontag, no stranger to illness, said that being sick was like being granted a passport to another country. He used to be my neighbour, I used to see him every day, but now he’s sick. And the whole world, the wideness of your world shrinks in sickness so often, so usually, the wideness shrinks until the whole world is just this small body, with its nervous system all lit up in pain. And once again the prince experiences this continuum of health (has he never been sick? This is what the story implies, the prince is kind of super human, or else, he is very forgetful. The way mothers are reputed to forget the pain of childbirth. No, I don’t remember being sick, being granted a passport to that country.) The prince sees a sick person for the first time, and then he sees a dead man.

Mark

I remember when I saw my friend Mark, he had died two days earlier, and this afternoon was going to be a visitation, a quiet family and friends short order casual thing. Funeral lite. When I get there his coffin is filling up the small living room like a wooden exclamation point, and then Mirha, his partner arrives, and announces that it’s time for the ceremony. She begins to work off the screws and winches holding the top on and then she lifts it and we’re all practically sitting in her lap because the room is so small and I don’t want to look at him. I’m looking but I don’t want to look, I don’t want to see him like this, dead and gone, and would there be an angry circle round his neck from the dog leash he hung himself with? Would his face be swollen and unrecognizable, and then Mirha is giving me earrings, they are going to get married, they were supposed to get married so it’s going to happen now, never mind until death do us part, we’re starting now. And there’s a first nations elder who says the words, and there’s smudging and smoke and I put the earrings on my friend and there are rings even they had bought together and then she kisses him and he looks like he’s going to wake up from his two day dream world but he doesn’t. Everyone in the room wakes up instead and everyone in the room falls asleep instead and I hop on my bike and I am shaking, shaken, and I don’t steer deliberately into the ordinary and indifferent traffic I get home and eat four peanut butter sandwiches, one after another, wondering how I am going to go back and see him again. You see things you don’t want to see and then your home is not your home.

This is how the story goes. The prince sees the four sights and then he leaves home. I remember my friend Peter saying, “Wouldn’t it be great to just walk out the door?” “What do you mean?” “Just open the door and walk out with whatever you have in your jeans. Leave. Everything.” He wasn’t depressed, he wasn’t at the end of it all when he this to me. Won’t you come with me, and leave everything you’ve ever known, we’ll just go wander out there without a penny. Beg for food. Find our truth out there. Practice not knowing. “Peter, why would you ask me questions like this?” The Buddha leaves everything behind, everything I mean wife and child and parents and cousins and aunts and he walks out the door, he shaves his head and becomes a monk. Some years later he finds enlightenment.

Of course, the story is not true. Or at least not true in the as it happened, I swear to tell the truth, kind of truth. It was an old Indian legend and became attached to the Buddha. His dad was not a king and the B didn’t live in a castle. His father was a member of the town council, and he was from a family of means, but what is true in this story and what is most important for our purposes, perhaps, is the fact that he leaves home. In fact, as I read this myth what I hear is the way that he is leaving home again and again. And how that leaving makes everything possible.

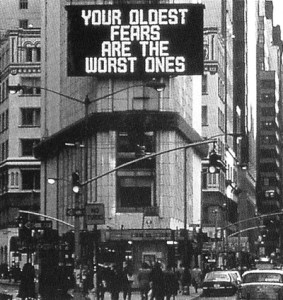

Glitch

The glitch occurs. The hitch, the hiccup. You see something you can’t bear to see, and in that moment, you have left home. Your friend, the one you relied on, trusted, he’s lying there and they’ve done something to the choke marks but you can feel them there, tightening up everything he wanted to say but couldn’t say, and now there’s no chance for you to say a word either. In that moment, when you see something you can’t bear to see, you have already left home. And you can go back, you can try to cling to it, but having left home, you will never be at home in the same way again. You will never be quite so perfect, quite so contained, quite so small, as you were before. There’s no rewind, no erase button, no apple Z to restore some originary Edenic splendour.

I think this is the moment where practice begins, and the moment, perhaps that practice turns around. To leave home, again and again, not by absorbing the slings and arrows, the shock of the sick and the dead, but to leave behind the old certainties. What did the Buddha say about his enlightenment?

Awakening

“This dhamma I have reached is deep, hard to see, difficult to awaken to, quiet and excellent, not confined by thought, subtle, sensed by the wise. But people love their place.” Their place. Isn’t that another way of saying home? Isn’t that another way of saying: But people love staying home. They love, we love, staying close to what we already know, the comfort of the old answers and the old questions. The Buddha goes on: “It is hard for people who love, delight and revel in their place (in their home) to see this ground: this-conditionality, conditioned arising.”

Moment

The Buddha leaves home, and he arrives at an unimaginable place. This moment. He arrives at the most unimaginable place. At this moment. This moment of practice. This is the ground, these are the conditions, and they are arising, and passing away. What is the fundamental nature of all sensation? Arising and passing away. Even the most fixed and solid and enduring. Even the dictator in Egypt, he stays in power for three decades, people live and die under his rule, but even this rule arises and passes away. Fundamental law of nature, of impermanence. Look: the dictator is leaving, the mountains are walking.

In other words: how can we create the revolution inside? How can we create the revolution outside? We leave our homes. We leave our tried and truisms behind. “Not confined by thought,” the Buddha said. Those old grooves, those well worn, super highways of the brain that include, first of all, the very first place we call home must be: our core story. The one that’s just a few words long. I am… fill in the blank here. It’s the core wound, “That moment, that cut” Lacan says, that moment when you are cut. Perhaps you are a baby crying for food and your parents aren’t around. Perhaps you see a child being slapped by her father and you don’t run over and save them. Perhaps someone touches you, someone you’ve trusted, someone who is trust touches you and cracks your body apart and you swallow this mantra, “I am dirty.” “I am unlovable.” Or: “I am not enough.”

Origin

In the next few weeks we’re going to talk about the four noble truths. They are laid out in the very first dharma talk the Buddha ever gave, dished out to a few of his pals in the Deer Park, deep seekers, people who had undergone great privations and sufferings, people for whom the most important thing was not comfort, but freedom. They wanted to be free. And he wanted them to be free, and so he shared with them this radical insight into the human condition, an insight that would become the basis for a culture of awakening, as the Occupy Movement would put it, as the Buddha put, as the Batchelors so helpfully remind us, again and again. These noble truths, this dharma, is not a religion, not a church, but a culture of awakening. And perhaps at the root of that culture we might find a prince, oh yes, that’s you, leaving your castles, your certainties, the touch of everything that is safe and familiar, and plunging into a place of not-knowing. Perhaps this is the origin of practice, the origin of a culture of awakening. Perhaps it all starts when we can leave home, at every moment when we can listen to that sound, do you hear that sound? Without giving it a name. In every moment when we can listen to the words of our mother and father, without having to name them “mother” and “father.”

5-Year-Old

So this is the situation: you’re a five year old girl. And you didn’t vote to be a girl, you didn’t vote to be in this family. Tell me, did anyone here vote for the atomic bomb, the home computer, Styrofoam cups, bottled water? Dogen voted for mountains. So you’re a five year old girl and your dad he’s saved up every bad thing that’s ever happened to him and he’s put it in a box labeled My Daughter. That would be you. You, the five year old girl. So every time you put on your coat, or do your homework, or play outside, or come back from school, he reminds you what a lazy, good for nothing, ugly, stupid, horrible person you are. Thanks for the inheritance dad. It wasn’t enough to have your crappy genetics, the protruding nose, the tendency towards depression, the flat feet and spinal bifida occulta tendencies. No, you had to give me all that self hatred and disappointment, that daily assault rifle of your mouth trained at my heart until I stopped feeling anything at all.

What is the nature of all sensations? The nature of all relationships? Arising and passing away. Fundamental law of nature. So you get older. You don’t vote for getting older, but you get older, and you leave the house, and because you’re smart and resourceful and you’ve learned to look after yourself, you become a nurse. You like to take care of other people, maybe because you know what it’s like when someone who is entrusted with your care, doesn’t look after you. OK? And you take a breath and you’re 20, 30,40,50 years old. And then dear old dad, the fucking tyrant, gets Alzheimer’s, is that something you get? And it doesn’t happen all at once, he starts forgetting things, like his keys, and then his mind, and then his personality, and slowly but surely he turns into a helpless child of an adult and because you are metta superstar nurse of the year you take him in. There really isn’t anywhere else for him to go. And this funny thing happens because when your friends come over they love him. I love your dad, he’s so great. He’s just this super happy open friendly child really. Most mornings he can’t remember your name, he doesn’t really have any idea of who you are. He’s here, he’s right here, in this moment. And your friends see him and they laugh their ass off, they sit their in the full radiant shine of his acceptance, his beautiful, surrendering openness, and because he is so busy surrendering they surrender too. Everyone surrenders, except for you. Because you’re carrying, you’re carrying, you’re carrying the terrible load, the terrible weight, the awful shadow of the very real things that he did to you.

And here’s the really strange thing we do as human beings. When something’s really fine and flying, it flows right through us, from the very top of the inhale, to the very bottom of the exhale. We’re all the way in it, and then it releases. But when something really shitty happens, we grab onto it, we hold on tight – you’re not going anywhere – and we bring it inside, put it away in some dark place where it can grow and fester and become worse and worse. The good times are Teflon and the bad times are Velcro, blame it on the hardware I guess. So the question is, the question you’ve been dealt from the very beginning remains: can you leave home? Can you put down that big word of father, can you just leave it there on the shelf, and stand in front of this big bubbly radiant Buddha, the one who used to be a monster, the one who used to be your personally customized tormenter, and stop calling him father, and stop calling him monster, and stop calling him anything at all, and just sit there, in this moment, the two of you in this moment together. He’s left his home, can you leave yours?

And maybe you can’t, can you be ok with that? Can you make that OK? You’ve made it OK for so many others, can you make it OK for yourself? Can you leave the home of that familiar self punishment?

What is the practice of leaving home? What does it look like, as a practice? When he rolled into Hart House last fall, Bernie Glassman gave us the whole of the dharma in three not-so-easy steps. And the first step is: leaving home. Bernie called it “not knowing.” The first step is not knowing. How can we practice not knowing? How can we practice leaving home?

You know, recently I was speaking with a friend and she said to me, “I’m the kind of person who…” Do you ever do this? Announce your traits. It’s like those one line movie descripts. I’m a romantic comedy with a thriller twist. It’s like you want to get to the end before you’ve even started. Maybe it’s the anticipation I can’t bear. I’m a very impatient person. Do you ever do this? I always forget things. Always. She turned to me and said, “I don’t think I’m a very caring person. I only really look after myself.”

And I wanted to ask her, “What if that weren’t true all the time?” I mean what if right now, right at this moment, what if you hadn’t decided? What if it was mostly probably true a lot of the time, but what if it wasn’t true all the time? What if there were some part of your life where that hard truth about yourself wasn’t true? I’m a pretty messy person. I’m a pretty stupid person. I’m a pretty person. I’m an ugly person. I don’t know how to talk to people. I’m very in touch with my emotions. And what if you weren’t? I’m pretty anal, I need everything around me to be cleaned up all the time. And what if you didn’t? What if today, for this moment, this afternoon, you didn’t clean up all the time? I mean, what if all there was no “all the time?” What if there were only moments, conditions arising in moments, arising and passing away.

When someone tells, you, when your best friend calls you up and tells you about their latest heartbroken computer dating misadventure, can you refrain from knowing? Knowing what to say? Can you stop yourself from offering advice, and remedies and fix-it solutions? Can you sit in a place of not knowing and not deciding, and can you offer that space to your friend, that spacious arena of non-judgment?

Not-Knowing

What is the practice of not-knowing? What is the practice of not-knowing in a culture that is only interested in answers, while you are busy becoming a question. In a culture where the person at the front of the room is the authority, the expert, the one who knows more, isn’t that why they’re talking? They must know more. What if they knew less? What is the person at the front of the room actually knew less and less? What if we could model our difficulties, our hesitancies, our awkward silences, our inabilities? What if we were tired of being strong and perfect, tired of our perfect castles? What if we kept breaking down and stopping? What if our hesitations were more valued, more treasured, than our good jokes, our beautiful sentences? What if we could give our milk and our attention to the ugly and left behind and forgotten faces?

“But people love their place: they delight and revel in their place.” Their place, their home. People love their homes. Their home truths, and then there’s a space that your best friend gives you – is that why they’re your best friend? Because you can trot out all your versions, the stardust happiness, the happiest person in the room, the liar, the jealous partner, the grieving son – you put on face after face and they’re still there saying yes. And when you look at your best friend saying yes, modeling yes, insisting yes, this too, it feels like you can do it too, that you can let go a little more, let go of that, let go of that, old bad familiar feeling of oh god, it’s me, again isn’t it? The more you look into that sweet sun of a face the more you feel yourself leaving home. Isn’t that what you’re doing together, with your best friend, again and again, leaving home, as if you weren’t the one, that one, the one who always, the one who is always, no not always but only sometimes, the benefit of every doubt and then doubt itself. With your best friend you become the question falling into each other’s faces until you are also saying yes.

Politics

To put this yes in political terms, to put this state of not-knowing in political terms, to talk about the practice of leaving home in political terms I think it means embracing the radical promise of democracy. All the faces, and the horrible ones, and the untouchable ones, and the unmentionable ones. A democracy of yes. What are the roots of compassion of care? I think it comes from a deep acceptance. Of saying yes. Or of not knowing. I don’t know but I’m here. Bernie Glassman’s second law of the dharma: First, you plunge into not-knowing. And then you bear witness. You bear witness. You say yes to whatever you see. You open to whatever is in front of you.

When I think of democracy I think of the country that is teaching every one of us right now how to practice, because they are practicing it so diligently moment after moment. I’m thinking of course, about Egypt. They have so much to teach us, in Egypt. Here are some words from Motaz Attalla, an NGO educational activist, talking about his experiences in Tahrir Square. It’s excerpted from a really stunning interview with Warren Nilsson.

Egypt

Motaz Attalla: “All we had was each other and this space and some crackers and cheese and so there was no choice but to resort to a different language. And I think it is very important that it happened because we were able to taste that different language and taste possibility. It was an affective experience – of being looked at a certain way, receiving a certain kind of smile or a pat on the back. Very, very simple things that suggested the possibility of being with other humans in a certain way and that have, when you think about it, certain political implications and organizational implications.”

Can you hear what he is saying in these words? The way they are in the square, they are the new democracy. They are the new state. Can you hear that the new state is being made here, face to face, toe to toe, word after word, it’s all here in this moment, this moment here is the revolution, is the moment of awakening. And he goes on.

“And to some extent it still exists. There is an affection – a romance even when we meet each other, talk to each other, see each other at events – this sense that we’ve been through this amazing thing together. But now that we’re back to the world of fighting over how we want the future to look, the default is to fall back into more of a mental exercise. The programs proposed by some of the new political parties are just incredibly naïve for me because they are recycling the same paradigm in terms of what is expected of a state or a parliamentary system. And I feel there is a challenge to break that down and to give more space to the Tahrir Square sentiment…

Some of the people working on police reform are realizing that it’s not enough to simply restructure the current system in order to rid it of corruption. We need to revisit the very notion of security… What is security? What is safety? What is community well-being?”

Can you hear him asking these questions, and inviting himself, and inviting us alongside him, to become these questions? He’s not asking: why are the soldiers shooting at us? He’s not asking: why are the police beating our sons and daughters? He asks the question beneath the question. What is safety? And then he goes on becoming the question:

“We need to be asking ourselves when have we felt safe in our lives, when have we felt secure, when have we felt that we have been able to contribute to other people’s feelings of being safe and secure or to our own?

And the same with learning. Instead of jumping head first into reforming the education system, we need to take a step back and listen to what our experiences have taught us about learning. What are the most important things that I have learned in my life – that have helped me to be a good person in my family, in my neighborhood, in my work, in my civic duties? What have I learned, where have I learned it and what are the kinds of conditions that have enabled that kind of learning? And to start to distill from that a sense of what an education establishment would look like.

And around health, what is my experience of physical and mental well-being? What are the spaces in which I’m able to feel that more? What are the times when I’ve been able to feel well with doctors or in hospitals?

This is the time to revisit the core principles within a lot of these sectors as part of that re-imagining of the sectors. Partly to root our ownership of them mentally back into our experience.” (The Promise of the Square by Motaz Attalla, www.organizationunbound.org)

These questions are rooted in personal experience. Did you notice that, again and again, he’s not talking about some idea out there of security or education? Security, education and democracy is here, begins here, in this place, this is what the radical democrats of Tahrir Square are telling us. Are insisting to us. This is where we are going to find the roots for our revolution, for the possibility of our leaving home, for the possibilities of a new way.

What makes you feel secure, when do you feel secure? And from that feeling, that feeling of democracy in you, in your own life, that’s how we’re going to build this democracy. This is not a religion, it’s not about following the ancient laws, it’s a culture of awakening that has developed practices, techniques and technologies to bring us to the radical invitation of this, exactly this, just this, this perfectly imperfect moment. One failure, one face, one hesitation, one uncertainty, one occupation, one question at a time.