(talk given at Centre of Gravity, Toronto, March 24, 2012 at an all day sit)

I’ve been haunted by this question lately, I wanted to share it with you, I hope you might be able to help me with it. Tell me: what does it mean to sit here, like this? In this way. To strike a pose, as Madonna might put it. Or as Marcus Boon might name it – in his book about all things copyright, and all things copywrong – I think he would call it copying. What does it mean to copy this pose? To turn my body, to turn your body, into a copy? This is how the phrase and invitation goes: to sit like the Buddha. To take up the mudra, the seal, the posture, of the Buddha.

To sit like the Buddha.

So often when I hear these Buddhist hand-me-downs I watch two sides come together in the sound of one hand clapping. To sit like the Buddha, as if I was not myself. Not this self, but someone dedicated to copying, to replicating a gesture, to striking a pose. Perhaps this pose is part of a whole succession of selves, a succession of postures. Have you been feeling that lately? Is that why you’ve come here today, for instance, because you can feel some space, a little bit of breathing room perhaps, between your self presentation models? Yesterday when I woke up I was a hundred pounds heavier, I was so tired, and it felt so good to be tired, to feel the gravity of this body. You know? Today when I woke up I was so sad. I was as heavy as my brother who is going through his own succession of postures, today he’s the one recovering from his latest bout of brain surgeries, the one whose illness has become a condition. It happens so fast, it happens like lightning striking, you’re sick, and then it turns into a condition. In other words, it turns into the thing you are. Into the person you’ve become. You wake up in the morning feeling sad but it’s not enough, the mind reaches for the inflation button and then you’re a sad person. You wake up feeling heavy and it’s as if you’ve been heavy your whole life. And while sad or heavy or happy are all true and real, they true and real in the moment of arising, in the moment they come up. Sometimes it can be difficult to let them go, to let my illness go, so that it doesn’t become my whole life, my whole condition. Even when it feels bad. Have you ever noticed that? Sometimes it can be hard to let go of a feeling particularly if it’s a bad feeling. Particulary if it’s a familiar old bad feeling. Welcome back heartbreak good old buddy old friend old pal of mine. Welcome back anger, where have you been, I’ve missed you. It can be hard to stop turning my bad feeling into a condition, into some aspect of my fundamental nature. As if it’s who I am.

To copy this pose, to strike this pose, as if I was, as if we were, the Buddha. This pose, in a succession of other poses. Downward facing dog. Revolved triangle. Instead of a self that is fixed in time, permanent and unchanging, maybe there is a series of postures. Can you imagine your life as a long asana sequence, as a long yoga series? Maybe there are a whole lot of going to bed poses, going to bedasana, getting upasana, breakfastasana. Instead of a self, instead of: I’m eating this breakfast. I’m feeling heavy this morning. instead of always this I, me and mine.

Whenever I hear this word I, I can hear the echo of an old God, some longing for certainty. Please don’t let it change. Please let tomorrow be like today.

Most of my friends speak about themselves as if they were a single thing their whole life. The hills and valleys – they’re all my hills and my valleys. But the Buddhists say, don’t they say it? Don’t we say it, sometimes? That the self is not a God. And if this self is not a god, then it must be busy being born, again and again, and it must be busy dying, again and again, in moment after moment. This is the description the Buddha offered of dependent origination. This is the crux, this is the thing itself of his enlightenment, isn’t it? What did the Buddha wake up to? Dependent origination. Which means? OK, here it is, the whole of the dharma in four words. Because this, then that. That’s all there is. If you plant the seed of an evergreen tree, an evergreen tree will grow. Because this, then that. If you plant the seed of an evergreen tree, and you want a maple tree to grow, and you are a good person, a devout and pious and helpful and beautiful person, what an excellent parent and neighbour and friend you are, everyone respects you, and you make prayers and burn incense and do sitting meditation and go on retreats and you donate generously to the Centre of Gravity and every night you pray, please please make the maple tree grow out of the seed of an evergreen tree. Will the maple tree grow? No. Because this, because this seed, then that tree. The view, the hope, that this seed will turn into some other kind of tree, does not affect the seed. I don’t know whether you’ve ever done this in your life. I plant the seed of anger, and in return I receive anger. Why is that person so mad at me? I plant the seed of complaining, of negativity and aversion, and bad things seem to stick to me. To me. Why do I have to feel so bad?

If you plant a watermelon seed, then you get watermelons. The Buddha insisted that this is a law of nature, fundamental law of nature. Nothing metaphysical about it. Law of nature. Of course these seeds need sunlight and water, these plants grow out of conditions. Like we grow out of conditions. Again and again.

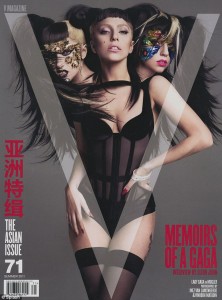

When Lady Gaga rolls herself out in a video she appears as a corn husk chewing farmer girl and the boy who is courting her playing on the piano, and a vamped up, half drowned, s/m queen, and a street fighter, and a him and a her. Isn’t the he that is a she already offering us not only gender as a performance, but the self as a multiple? Look at me. Look at all the meeeees. I’m becoming all these selves. I’m making room for all these selves. Can you make room for all of yourselves? I think we all have some recognition of our own multiple selves, even if we can’t star in our own multi-million dollar promotional loss leader cross platform video giveaway. I think there’s a certain version of ourselves that we play for our parents, and another with our best girl friend, and another for our best boy friend. And another when you touch me, and another when you don’t touch me. And the illusion is: it’s all me.

Jacques Lacan, French inheritor of Freud, the writer of difficult sentences, spoke of the mirror phase, a key moment in development. The child experiences themselves as a field of sensations, its boundaries in a tremendous flux (am I eating my own breast? Is that my foot or is the floor my foot?). When a child chances across a mirror, all of these multiple in and outputs appear all at once as a single being. You have a continuous line, a continuous bodily perimeter line. You look like you are one thing. It’s a very powerful expression.

I don’t know if any of you have seen the famous horrible film experiment of the Russian filmmaker Viktor Kossakovsky, who didn’t allow his son to look into a mirror for the first three years of his life. One afternoon, when the light was right, voila my child! He leads his boy upstairs where there’s a floor length, one way mirror waiting with the camera parked behind it. Is that… me? For 45 minutes we watch him watch himself. The test tube of a life. It can be difficult to live with a filmmaker. Lacan says that this mirror stage moment is located in an early developmental stage, and it helps us produce a boundary, a perimeter, it helps us contain all these firings that are going off in every direction.

But I think the mirror phase happens again and again, that we are fooled by the apparent continuity of our body. I look down at my hand, I feel the pang in my stomach and think: that’s me. I’m in one place therefore I must be one thing. If we are one body, we must be one thing. Call it: an understanding that is skin deep. But when you steadily abide, when you give yourself over to noticing, you can see that this hand is changing, this face is growing older. You notice it instantly when you meet up with someone you haven’t seen for a few years. “Oh hi,” it comes out of your mouth while you think to yourself, ”Oh god, do I look that old? Am I also dying?” You see the changes in their body, you notice every new line and wrinkle. What used to be there, is not there anymore. Could we call this: striking the pose of someone getting older? Change is going on at a molecular level, this is what the physicists are telling us, what the biologists are telling us. Every seven years all of the cells of this body have regenerated, there is nothing left of the one who answered to my name seven years ago. The physicists would say, like Madonna, like Lady Gaga, that we are a field of possibilities. A series, a succession, one after another. Definitely not a thing. Certainly not a God, not fixed and forever, not that.

No, not a God. But perhaps, at least sometimes, a Buddha. Perhaps one of these selves, one of the cards in the pack, one of the stars in the constellation, is a Buddha. To sit like the Buddha. In other words: to sit like yourself. Your Buddha nature, they call it. To sit in the midst of the difficulties, the turbulence, the ebb and flow of your life, to plant yourself squarely in your life, like the Buddha. Striking a pose. Perhaps this is the pose that allows all of the other poses to unfold and unravel. And what is the pose of the Buddha about? How do you meet all of your selves? With stillness perhaps. With a pose of stillness, that meets the rush of all that is arising in this moment, all of the selves of this room, all of the selves of your neighbours, and this floor, and these vents, to meet all of that with stillness.

I think this pose of stillness – to sit like the Buddha – is about a fundamental shift in how we regard what the brain does. Because mostly the brain is a reactive organ. Out of the conditions arising, because this, then that, the brain is busy saying, “I like, I don’t like.” Because this, then that. The brain is all that, responding to this, the brain does that, then that, then that. Again and again. Following its own course of well worn habit patterns. And these habit patterns are so often pushed forward in order to fortify some idea of what we imagine is this self. The practice, the practice of stillness, the practice of mindfulness, is designed to show us these patterns, and soften the reactivity. In other words, to turn the brain from an organ of reaction, to an organ of curiosity. Meet one of my old selves: the self of reactivity. Meet one of my fave new selves: the self as detective. The curious self.

The detective asks: What’s happening? Oh look, what is going on, over here? The brain answers: Crushing jealousy. And then the beginning of the crushing downward spiral. How could my best friend have said that terrible thing to me? The detective asks: What does this feel like in the body? And then the detective notices: Jealousy, it’s not just an idea, it’s a tightening in the throat. The detective asks: how far down does it go? It plunges into the sternum. Fascinating. It has a dark underside, and then there’s a sliver of something light in it, and a restless bubbling from the bottom to the top. Those sensations, those actual embodied sensations, are what I sometimes name as jealousy.

When you strike a pose, when you sit like the Buddha, when you’re practicing, when you’re meeting the too muchness of your life with this stillness, you might become curious, curious about your life. Not the idea of your life – not the way it’s supposed to be, the person you were supposed to become, the one your internalized parents, the God substitutes, the best friend you idealized in high school – this stillness can allow these ghost selves, these phantoms, to drift by without having to hold onto them, and squeeze out a little more delicious unhappiness juice.

What does it feel like, in the frame of the body, when your best friend says that wonderful terrible thing? What does your lunch actually taste like? What does brown rice or a cheese sandwich actually taste like? What is hunger? Not as an idea, but what does it feel like, in the frame of the body?

Can you be curious? Can you sit like the Buddha, unmoving? It doesn’t mean you don’t have feelings, it’s not about escaping. On the contrary, it means feeling that feeling right down to the end of the exhale, and not escaping into cascades of negative patterns of abstraction that shoot you away from this actual moment. When I get hungry I can feel this clenching in my stomach, like it’s a mouth trying to close around something, and then there is something wet at the top of that stomach wall, and it’s met by something dry at the bottom. Like I’m drying out. And then there’s a voice that says, “Hunger.” And it gets louder and louder, like someone turning up the volume switch, until all the other thoughts I’m having, all the other usual distractions and laundry lists and rehearsals for encounters, and replays of past encounters, they are all slowly buried by these voice that is now shouting over and over again: HUNGER. HUNGER. HUNGER. In other words, mostly my experience of hunger is linguistic. It’s an idea. A repetitive, compulsive idea. Is it possible to stay here, here, in this room, even when it’s difficult? Even when the climb is steep, and the going is hard, the compulsive repetitions arrive? Is it possible to drop the mask of reactivity, of anger, of self defeat, of happiness and unhappiness? Is it possible to put those masks on the shelf and wear the mask of the Buddha? To sit like the Buddha.

Today’s sit will bring us to a church. It is part of a series of situational sits, where we’ll sit in a traditional place of practice like this, and also in an untraditional place. A place where we can rub our practice up against. To be in a church again. I wonder if sitting like the Buddha, to take up the mudra, the seal, of the Buddha, to copy the Buddha, means also: going to church. Do you think it could mean becoming the church? How do we become the Buddha? How do we realize our Buddha nature? Perhaps by entering the good and bad of this moment.

Perhaps the church is something that is out there, as an architecture, as a place that gathers up certain qualities of attention, certain residues of dedication. It is a place that lives out there, and it is a place that lives in here. My church, myself. My church, my Buddha, myself. To take refuge in the triple gem, the triple gem of the Buddha, the dharma, the sangha. To step into the church of yourself, perhaps this is part of today’s invitation. Is the mud on my bicycle wheels holy? Is my inhale holy because it’s coming from your exhale? Is this statue holy? As holy as your face? Is your smile holy? Is your frown holy? When you put your hands together in prayer are they holy? When you feed yourself with those hands are they holy? When you feed someone else with your hands are they holy? When you wipe your ass with those hands are they holy? Are there selves that you reject, and other selves that you put up on a pedestal and worship? What does the detective say?

Can you make a church for all your selves? For all of the neglected and left behind and broken selves? For all of your small selves, the ones that can hardly speak, the ones that no one notices, mostly, most of the time, not even you. Perhaps this is what it means to sit like the Buddha. To open your hand, to open your heart, to the very smallest of your selves. To say yes, to open the door, to offer the mirror, to say yes I can bear to look at you, to admit that I know you, to admit that sometimes I feel like you feel too. In all of your smallness. Because what do we find in a church, in any church? People. The congregation. The choir. If we are the church, we must also be the congregation. We must be the voices of the choir. And this I think is also part of the invitation: how to listen to the choir of our unheard voices. This is what the Buddha seemed to be always busy singing. The choir of our unheard voices. The difficult places, the wounds, the wounds that are also the path. On this rock, on this wound, I build my church. Tell me, is there anything in this room, is there anything in this city, is there anything in your life, that isn’t a church? Perhaps the church, the architecture of the church, is there to remind us that churches are everywhere. Perhaps our churches are there to remind us that we are churches. Whenever we strike a pose, and remake ourselves as a copy, and sit like the Buddha, waiting in silence, in silence and curiosity, listening for the music of our unheard voices.