Canadian Artist Spotlight: Ross McLaren

I knew Ross as a filmmaker, collaborator and the founder of the Funnel, the most important locale for experimental film in Canada. It wasn’t just the man’s charm, but his films — awkward, jarring, disjunctive, and, of course, ironic — which grabbed my attention. It was the late 1970s. It was punk. No one followed, everyone did what they weren’t expected to do. No reverence for commercial film, no desire for distribution. You made films because they needed to be made. Why not try it this way; let’s see what it looks like. A failure in film was a celebrated success.

And there was Ross, a Sudbury boy in Toronto, recently graduated from the Ontario College of Art. McLaren began his career co-founding the Toronto Super 8 Film Festival, the first in Canada. His film Weather Building (1976) is emblematic of this period. Super 8, edited in camera, science fiction meets visual abstraction. It is a dissolving, collapsing, repeating visual. It is the antithesis of Warhol’s ponderous Empire State and a sly homage to Michael Snow’s incessant panning camera. With its off-screen sounds, footsteps, wind blowing, there is an uncomfortable energy in Weather Building, and simultaneously something very cerebral in its abstracted imagery. The film is an enunciation of the time.

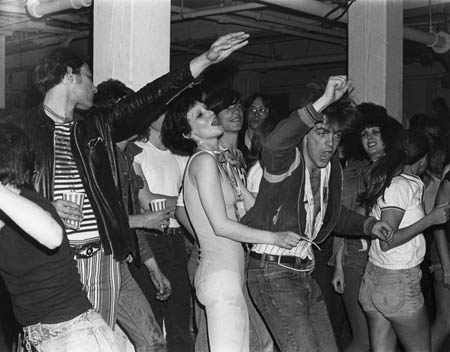

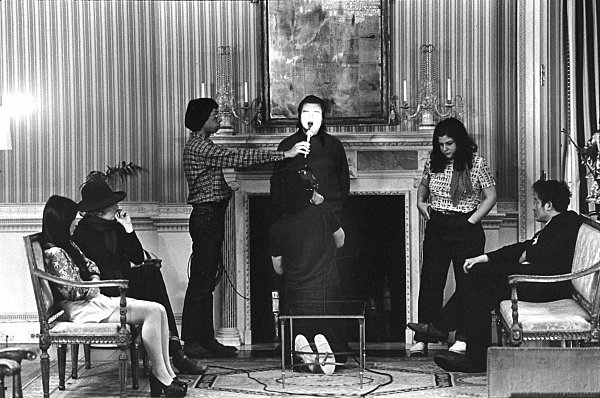

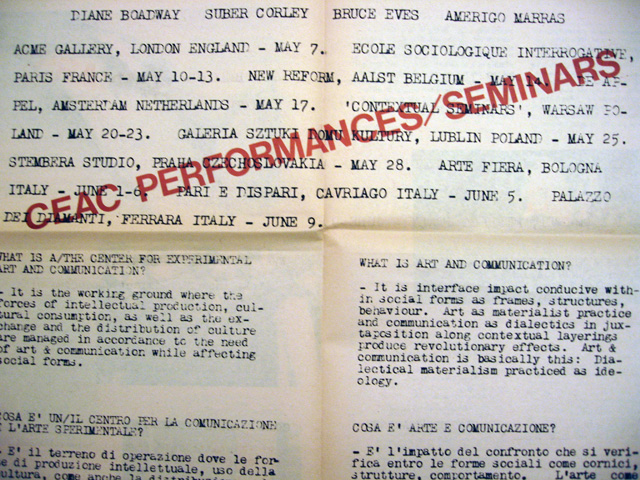

It is 1976. McLaren is actively organizing screenings of films in the basement of the Centre for Experimental Arts and Communication (CEAC), a non-institutional, revolutionary art space operating at the edge of the edge. CEAC’s mastermind and director, Amerigo Marras, gay, young, was an architecturally trained anti-advocate for the status quo. He had grown up in radical Italian politics so, in the fresh cultural territory of Toronto art production, he was willing to open his cultural space to whatever was tough, Marxist, advocated world change, and had no time for history and its lies. Here, one was confronted. Here, in the art basement, McLaren created his seminal Crash ‘N’ Burn (1977), named after the short-lived downstairs punk club. With a wind-up 16mm Bolex, he films in silence a visual rendering of the rancorous. Jerky, rough, in grainy black-and-white, lead singer after lead singer takes off his shirt, gyrates, shakes his ass in the face of an audience who scream and jump up and down, up and down, their bodies, the camera. In the film, the audio is not synced to the visual, but this is seamless disjunction. The once-stars of early punk, the Dead Boys, Teenage Head, and the Diodes pass as McLaren zooms in and pans. It is a documentary, yet not. Scratches on the film reverberate with the snarling performers who want nothing more than to announce destruction, feign their own deaths, and draw knives across naked emaciated stomachs.The celluloid explodes in raucous frenzy: discordant, awkward, and pertinent. These are not folk singers, these are suffering punks who scream out to us: “I’m in a coma/Pull the plug on me/ I’m in a coma/please listen to me/I’ve got the right to live, I’ve got the right to die.” Isn’t this what it’s about? Kill me, it’s so fuckin’ boring.

While downstairs at CEAC the punks had screamed, five floors above Amerigo and crew organized an event for every day of the week and published Strike magazine. When Strike printed a grainy black-and-white-and-red cover photograph of Aldo Moro’s bloody body in May 1978, what occurred was a political firestorm in Conservative Ontario. Within days, all funding was withdrawn and the RCMP were at the doors. It was over in an instant. The art community went into a coma of fear; with hardly a word of protest in defense, CEAC collapsed. McLaren propels out of CEAC’s womb, tears off, landing at a small warehouse at the eastern end of Toronto where he finds a new home for the Funnel, an artist- controlled location for the making and the showing of film.

The Funnel had begun quietly after the Crash ‘n’ Burn club had shut down in the fall of 1977, operating in the CEAC basement rent-free until the 1978 incident.It was at the Funnel during the late 70s and throughout the 80s where those of us making films in the pure pleasure of self-indulgence found a supportive audience. Who cared that only a few saw your work as long as you were free to play with the media in every way possible, from over stylized narrative, to John Porter’s single frames of speed, or Michael Snow’s texts melting on found stock. It was the Funnel where you could create films for an uncompromising audience. Here, you could watch on a Friday night the latest efforts at the mutated incarnation of film. Here you could watch their films and meet some of the world’s most highly respected artists.

A who’s who of the avant-garde scene exhibited and discussed their work with appearances by Kenneth Anger, Robert Frank, Warhol Superstar Ondine, James Benning, Valie Export, Jack Smith. Ross organized, promoted and made it possible for everyone to create and show their films.

One of the first films McLaren showed at the new Funnel was Summer Camp (1978), called by the Globe and Mail’s Jay Scott: “One gruesome delusion after another… funny and grisly at the same time.” It is a banal, absurd film constructed of endlessly repetitive outtakes from a CBC audition for the cast of a television program, “Time of Your Life,” centering on youth culture. It is shot with a kinescope camera, an early hybrid video camera that recorded in 16mm film with an optical sound track. Each teenage actor undergoes a three-part audition: a short personal interview conducted by a prim CBC interviewer; a recital from memory of a fixed script; an improvisational dialogue with a hired CBC actor. The premise: the CBC actor portrays the brother dying of cancer. It is at this point, at the final stage of each audition, that the film takes a radical turn from a kitsch view of the amateur and the pathetic to the abject existential. The half-hearted, sweet questions of the interviewer, “What do you do in your spare time?” are replaced by the low voice from the hospital bed of the dying brother played by Peter Kastner (who later appears in Francis Ford Coppola’s You’re a Big Boy Now): “Can’t you do something to take me away from this place?” “The good times are over for us.” “It’s cancer in the final stages.” “I have three weeks to live.” So effective is Kastner that an auditioning teenager (who possibly studied in Stanislavsky technique) begins to cry, flowing tears. The humorous perversion of a 1964 CBC audition tape suddenly metamorphoses into existential angst. The banter, the empty dialogue, takes on signification: “It’s my life, it’s what I care about the most.” It is the punks again, screaming at the microphone about meaningless life and death.

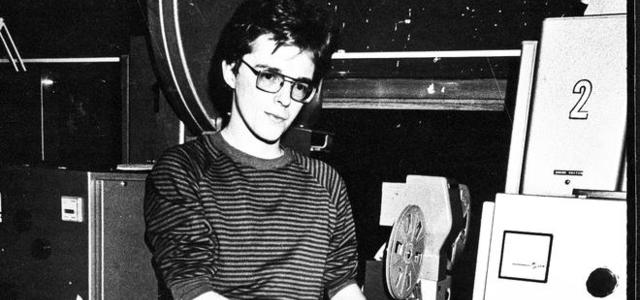

Under McLaren’s direction, the Funnel was involved in the entire process of filmmaking; as important as the screening of films were the film classes and workshops. Throughout his career McLaren has been actively involved with a pedagogical approach to film. His teaching efforts began in the CEAC basement where he would run film workshops, and continue today with his active involvement in teaching film and video at a number of impressive schools in New York, at Cooper Union, Pratt Institute, Fordham University, and Millennium Film Workshop. It is this impulse to foster artistic talent which was at the core of the Funnel. Many filmmakers and artists had their first public exposure at the Funnel Gallery and screening room. Ironically, some of Ross’ students have gone on to make commercially successful feature films and have been nominated for Academy Awards.

McLaren has been steadfast in his “shrug-of-the-shoulders” rejection of the conventions of narrative film. Not-quite-orthodox structuralism, his films help in pointing to the possibilities beyond standard film conventions. A film he made in the late 1970s, Wednesday January 17, 1979 (1979) is a perfect example of the other possibilities of film. McLaren is working at the Canadian Film Distribution Centre cleaning up the heads and tails of films, taking off the old leader and adding fresh leader when he notices the leaders are often more interesting than the films. So, he splices them together, includes dates in rough Letraset, includes a final date in the future (Monday October 18,1988), and includes one three-second representational visual, part of a clock. It was all about appropriation, so why not the refuse from the waste bin, celluloid without an image, leaders brought together? And suddenly in the rhythm of the projector, in the scribbles and scratches, life appears.

McLaren’s microfiche film, 9×12 (1981), produced as an insert for Impulse magazine, is almost orthodox structuralism. Shot in the Funnel gallery space, the microfiche card consists of nine rows of 16mm film, 12 frames per row, which when placed together form a still image of the visual space and when projected display the space deconstructed through time.

In Sex Without Glasses (1983), a mannerist play on the Hollywood rear projection process shot, there is a scene where McLaren portrays himself floating above the world. With closed eyes the somnambulist filmmaker floats over a giraffe, over the moon, over the crawling insects, a shadow, a silhouette of the artist. It is film noir with irreverent humour. A man standing in a leather coat with eyes closed, the sound of rain, a black shadow passes, the man walks off screen. There is no sex, and hardly any glasses in this movie. But there are shadows in the background, rain in the dark, and many distant, barely visual, out-of-focus images which invoke a dark, postcard view of life and death. A woman looks at the sea, a man drives, Niagara Falls flows backwards, a man and a woman embrace in an erotic slide into the rushing water. In the final scene a young couple in bathing suits stand facing the ocean, she cups her hand and whispers into the boy’s ear, we don’t hear what she says, they walk off screen together. Sex Without Glasses is quintessential Funnel filmmaking; an abstract tale told with an implied narrative, seminal McLaren. It is film that employs visual effects, but primarily is constructed in existential bathos. There is humour, but in a deadpan abject colour. The dying brother in Summer Camp tries with futility to illicit sympathetic responses from his auditioning partners, but with amateur superficiality only receives incredulous attempts at sympathy: “You’ll be ok. It’s probably an error. You aren’t really dying.” But he is. The film leaders with their indecipherable text and scratches are the evidence of the ravishes of time on our waste bin-appropriated lives. McLaren may appear on the surface as humourous, repetitive, deadpan, but something is amiss, as the voices don’t sync with the visuals, so McLaren’s message isn’t about aesthetic breakage and formulaic manipulation, but finally about the water flowing backwards, the brother dying and the sexless bodies looking out into the artificiality of the process shot.

— Eldon Garnet

For over 30 years, Ross McLaren has worked as a filmmaker, scholar, teacher,and curator. In his native Canada, he founded and was first director ofthe Funnel Film Centre in Toronto, an institution devoted to the production, exhibition, and distribution of film. Currently, McLaren teaches film and video courses at Cooper Union, Fordham University, the Millennium Film Workshop, and Pratt Institute. McLaren is an alumnus of the Ontario College of Art in Toronto. McLaren has shown his works worldwide. His films screened at the Museum of Modern Art (New York), the Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris), Documenta VI, the Biennale du Paris XI and XII, the Third Annual Avant-Garde Film Festival (London), Avant Garde Film Practice: Six Views at the Pacific Cinémathèque (Vancouver), and the Ann Arbor, Edinburgh, Oberhausen, and Toronto Film Festivals. Works are included in the permanent collections of the American Federation of Arts, the Arts Council of Great Britain, the Art Gallery of Ontario, the National Film Archives (Ottawa), and the National Gallery of Canada

Eldon Garnet is an artist and writer based in Toronto. He exhibits his photographic and sculptural work internationally. He was the editor of IMPULSE, an international magazine of art, ideas and fashion. His most recent novel is Lost Between the Edges published by Semiotext(e), MIT, New York.

Originally written for and commissioned by the Images Festival in Toronto who honoured Ross with an artist’s spotlight in 2010.

A Funnel For Talent by Anthony Hall

(Cinema Canada, February 1979)

Film has often been called the ultimate cooperative art form. But as film technology becomes cheaper and easier to operate, the necessity for collective effort declines. Increasingly, the individual can use the medium as a truly personal vehicle for artistic expression. In the late 60s there was a surge of interest in this new kind of alternative, highly individualistic cinema, but somehow no major outlets developed for it in English Canada. Groomed on the formula productions of institutional giants, film and TV audiences found it difficult to accommodate the raw directness of works left unrefined by the technical skills of highly trained teams of experts.

Finally there are signs that some of the obstacles are breaking down between movie viewers and the artists who want to make completely personal statements through film. The filmmakers compelled to take on all the technical problems of the cinema – from scripting to photography to sound to editing – are now concerned about marketing. Distributing, advertising and exhibiting are coming to be seen as integral parts of the whole art of filmmaking. The rapid development of The Funnel, Toronto’s new home for alternative cinema, is a powerful example of this process in action.

Primarily, The Funnel is a film gallery where works of alternative cinema are regularly shown and discussed, usually with the artist in attendance. Featured last year, its first year of operations, were the creations of Toronto’s rising generation of new wave filmmakers such as Keith Lock, Villem Teder, Bruce Elder, Anna Gronau and Frieder Hochheim. Also invited to show their work were a variety of artists from outside the region, like Byron Black of Vancouver, Taka Iimura of New York and James Benning of Oklahoma. Occasional evenings have been devoted to the offerings of particular institutions such as the Film Co-op of London, England. And once a month there are open screenings when anyone can bring in their films to be viewed.

Much of the material shown is on Super 8, the medium whose easy accessibility best corresponds to The Funnel’s democratic philosophy of film. The view of the art is well articulated by 24-year-old Ross McLaren, The Funnel’s founder and principal dynamo. “Anybody can do a film,” he insists. “The technical end can be learned in half an hour.” To McLaren, the layers of mystique surrounding the cinema have prevented individuals of modest means from realizing the form’s full potential. “There is a belief that to make changes it takes thousands of dollars and the expert knowledge of a great many people,” he maintains, continuing: “The result of this kind of thinking is that the media is monopolized by glossy films that are realer than real. Their production is modeled after a Detroit assembly line with particular craftsmen responsible for every stage of the fragmented manufacturing process. Like this the original concept gets watered down, and it is the concept, not the technical thing, that is the most important part of the film.”

McLaren in his own work, like most of the filmmakers showing at The Funnel, aims to move beyond the structural bounds confining commercial movies with their traditional emphasis on narrative. “Reduce film to light and emulsion and acetate,” says McLaren, “and start from there. Don’t even think of telling a story.” Accordingly, much of his varied output, such as the widely acclaimed I.E. and Weather Building, might be termed “experimental.” But associated even with this catch-all film category are a growing number of conventions, all of which McLaren seeks to escape. With his most recent production, Summer Camp, he evades practically all labels.

This 16mm black and white “feature,” notes McLaren proudly, was made for $400 – a budget much higher than most works shown at The Funnel. The film pokes fun at the CBC’s professional pretensions and their unimaginative way of adapting theatre for television. The movie is a straight assemblage of nine intriguing screen tests made by the Corporation in 1964. McLaren simply took hold of the footage as it was about to be thrown away and ran off a print adding only his own name on a credit. In laying claim to a piece of cinema in this fashion, McLaren calls into question certain assumptions concerning the nature of personal creativity. He provokes consideration of the limitations of an artistic form, much as Andy Warhol did when he placed a frame around a Campbell’s soup tin, or as Michael Snow did with his 45 minute zoom shot in Wavelength.

Many of McLaren’s other cinematic efforts, in spite of his disparaging comments about commercial filmmakers’ preoccupation with craftsmanship rather than concept, display an impressive degree of technical wizardry. They travel widely in the United States and Europe and have won their share of awards. But McLaren sees these victory garlands basically as hollow stamps of approval. “There are today so many festivals,” he explains, “that virtually every film done can win some sort of prize somewhere.” What McLaren seeks most from his work is the opportunity to talk about it with small groups of people and The Funnel was established to provide an environment where filmmakers can get this feedback – a crucial component of the creative process. Says McLaren, “Films are not only screened here but they grow out of The Funnel… The fact that a place like this exists is a good incentive to go out and shoot films because of the certainty that there’ll be a place to show them.”

Of course The Funnel is not the only place in Toronto where works of alternative cinema are exhibited. At the Art Gallery of Ontario, for instance, experimental films are often screened under the auspices of Ian Birnie’s Media Program. “but before works receive such prestigious, institutional recognition,” notes McLaren, “they have usually been around for awhile. What The Funnel does,” he continues, “is to provide a testing ground where people can show their films for the first time… where they can get a start.”

McLaren had no such outlet for his work when he began making films as a student at the Ontario College of Art. His resulting frustration prompted him and several friends to found the Toronto Super 8 Festival in 1976. But the initiators were soon muscled out by more commercially-minded interest who have since made the event, says McLaren somewhat bitterly, “little more than a trade show.” The Funnel was McLaren’s next venture into film exhibiting. This he originally established in a Duncan Street basement provided free by the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication. The partnership between CEAC and The Funnel proved short-lived, however, once the latter failed to back up the former’s publically proclaimed support for the Red Brigades. Accordingly, McLaren and the dedicated group around him have a new address at 507 King Street East, where renovations madly took place in anticipation of this year’s opening on December the eighth.

With the same low budget mentality they apply to their films, all the work on the new space is being done voluntarily by Funnel members. Many of them have offered their efforts repeatedly in the continuing saga to develop an environment in Canada where truly independent filmmaking can thrive. During the death throes of the Toronto Filmmakers Co-operative, for instance, six of the nine executive members who attempted to save the debt-ridden organization were committed Funnel associates. In spite of this similarity in personnel, however, it is asserted that The Funnel is not simply a replacement Co-op. “The latter was production oriented while the former is exhibition oriented,” explains The Funnel’s vice-president Tom Urquhart.

But while the two organizations have developed in different directions, Urquhart indicates that they both were started to meet comparable needs. On this he has a rare perspective, for Urquhart began working at the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre (CFMDC) in 1971 when it was located in Rochdale College across the hall from Cinema Canada and the fledgling Co-op. “During those times,” he reminisces, “the Co-op was created by and for makers of alternative cinema. Since then it developed into a cooperative for people wanting a stepping stone in to the mainstream of the industry.” That The Funnel’s growth represents, in part, a return to basic principles by a section of the Toronto film community is further underlined by the fact that one of its greatest supporters, Jerry McNabb, was the Co-op’s first co-ordinator. Today he heads up the CFMDC, the nation’s major repository for experimental films made by independents. On McNabb’s advice, this organization has agreed to pay the producer’s rental fee on any of its works that are shown at The Funnel. In addition, McNabb has recently hired McLaren.

Besides what it gets from the CFMDC, The Funnel receives some funds from the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council. With the unfortunate history of the now defunct Co-op firmly in everyone’s mind, however, there is an unwillingness to become too dependent on the government. Thus most of the money comes from the members themselves who seem willing to pay a substantial amount to be part of an exciting new enterprise. Perhaps one reason for this is that at least half the budget is recycled, largely among the membership, in the form of film rentals. McLaren and his colleagues are fast learning how to temper their altruism with a healthy dose of business savvy.

How The Funnel might develop in the future depends only on the energy and vision of the growing membership. There is talk of a publication, the creation of an archival resource, and the renewal of the workshop program that McLaren started last year. But almost certainly the emphasis will remain on exhibition, with stepped up efforts being made to widen The Funnel’s circle of contacts. Says Urquhart: “We want to bring the alternative cinema from international origins to the Canadian audience… and also encourage the showing of Canadian alternative cinema outside the country as well as across the country.” In Canada, The Funnel is at present most closely associated with PUMPS in Vancouver, the Atlantic Filmmaker’s Co-op in Halifax and the Newfoundland Independent Film Co-op in St. John’s. Anthology, Film Forum, and Millennium in New York. All share similar goals, as do a variety of organizations in Europe with which Funnel members will be exchanging prints. Anna Gronau, a committed devotee of alternative cinema, sees this kind of long-distance interchange of films as a particularly humanizing aspect of the so-called mass media. Says she: “It encourages the creation of small communities around the globe where people meet to watch the same image, but are left free to react in their own peculiar fashion.”

Gronau’s respect for the individual movie viewer’s integrity is paralleled by the concern at The Funnel that film should be used to show and develop the artistic uniqueness of particular personalities. In order to create an intimate, human environment where this can take place, McLaren and his colleagues have joined hands in cooperative effort. While the fruit of their work may well become an important influence on Canadian cinema, it will probably never attract the attention of a mass audience – indeed, the very concept of mass appeal runs counter to the Funnel’s vision.

Movies Made Personal by Jay Scott

(Globe and Mail, March 9, 1979)

The CBC interviewer tells the girl, a would-be performer with ratted hair and freckles and braces that she looks like Kate Reid. “Tee-hee,” says the aspiring actress. Canadian actor Peter Kastner, in an improvisational scene with another would-be, an actor this time, confesses that he is dying. The young actor thinks a moment and then says brightly, “Well, life doesn’t last forever!” A third teenager informs the interviewer in all sincerity that her studies at the Royal Conservatory of Music will be an aid to her when she sings the blues professionally.

It goes on for an hour: one gruesome delusion after another. The name of the movie, funny and grisly at the same time, is Summer Camp, an anthology culled by Ross McLaren from five hours of CBC audition tapes dating from the early sixties the auditions took place when McLaren was about 10.

H is now 25 and is the founder and director of The Funnel, Toronto’s major outlet for experimental filmmakers interested in the possibilities of movies as signed, personal statements – statements as intimate as a surreal etching, as self-descriptive as the results of a Rorschach. For the past several months, The Funnel, located at 507 King Street East, in a comfortably tawdry building that resembles SoHo in its better (ie. less affluent) days, has been host to programs of experimental films from around the world.

The programs are screened Monday and Friday nights (Summer Camp is part of a Ross McLaren retrospective on tonight) and are, within the confines of the label “experimental” – which usually, but not always, means inexpensive and unplotted – eclectic. One night, you can see a slick, full colour satire from California (Michael and His Things) which pokes fun at the tendency to define personality by possessions; another night (a week from today, to be precise), you can watch Michael Snow’s 4.5 hour opus, Rameau’s Nephew by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen.

But most of the films are short, from one minute to 30, and many of them resemble McLaren’s work – they rarely ask for viewer involvement in the conventional sense of suspending belief, preferring instead to treat the medium as a medium, with its own syntax. There are often movies about movies, reminiscent of the work of some painters (abstract expressionists, for example) who make paintings about paintings.

While The Funnel is supported by some government grants (Ontario Arts Council, Canada Council), there is an emphasis on raising funds by selling memberships. And most of the filmmakers whose work is exhibited function independently, sans financial aid.

“We do not cater to any market,” McLaren explains. “We deal with our own aesthetics, with our own formal concerns; it’s a way of getting back to individual expression in film without having to make the compromises called for in an assembly-line product. A large budget is not necessary – an experimental film can cost as little as the $5 required for a roll of Super 8 film.”

On the last Monday of every month, an open screening is conducted: anyone who has made one of those $5 statements can bring it and have it projected. Thus, the Funnel, which attracts an aesthetically elite audience on the one hand, can be seen as the city’s most democratically accessible outlet for self-expression in film on the other.

The Funnel and Me by Ross McLaren

From catalogue: Toronto: A Play of History, Toronto: The Power Plant, 1987.

The following is a personal reflection on my experiences in the Toronto film community over the last ten years. It is not meant to be an objective, theoretically-based analysis but a history, written with the realization that otherwise these events might not be recorded, given an arts scene whose memory is somewhat selective. It is also important to note that my experience as an artist/filmmaker is closely tied to the history of The Funnel Film Theatre which I founded in 1977.

Originally, my intention was to construct a media centre for the production, exhibition and distribution of film, art or whatever happened to congeal and mutate. As the long suffering debate over the Canadian film identity festered in the alphabet soup of organizational CFDCBCFINBB’s I thought a happy solution might be to forge a film gallery in some warehouse pace and actually develop an audience for these orphaned film gems. A live-in basement space was generously donated by the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication (CEAC) and for one glorious year I lived a boiler-room existence while building an eager audience for these challenging works. Everything seemed to be progressing smoothly until CEAC, on a trumped-up terrorism charge, had its arms-length government funding hacked off at the shoulder. Kneecappers kneecapped! Carefully dodging RCMP phone taps, The Funnel friends of film somehow managed to prove we were not, in fact, members of the Red Brigade, and regrouped in a new location.

The word ‘Funnel’ seemed to be a good name for what we were doing. I needed an ‘F’ word to go with ‘film,’ and I also like the ambiguity associated with it. Anything could happen at The Funnel, and often did. Because The Funnel was Canada’s only ongoing showcase for independent and experimental film work, I felt a curatorial diversity was essential. Otherwise, the potential conflict of interest inherent in filmmakers who curate might result in shameless self-promotion. This has far too often been the case in Canadian experimental film programming.

During my three years as Programmer, I tried to maintain a balanced menu of international, Canadian and local work. Monthly open screenings where anyone could project absolutely anything in a spontaneous, informal context served as an important forum for works-in-progress and for discovering new talent. Working with a small budget and much volunteer labour we managed to raise the visibility of these films in Canada and also have our work screened internationally. Forming links with filmmakers and organizations in other countries was crucial as experimental film was getting very little recognition in the rest of Canada.

With this major step of organizing the artists’ film community, and due to the immediate popularity of the screenings, the arts councils were persuaded to lend some initial support. These organizational funds have continued over the last ten years, but production grants for individuals involved with The Funnel have been less frequent. In addition, Funnel members have rarely been asked to take part in the jury process. Juries are often comprised of commercial producers, out-of-touch academics, or filmmakers demonstrating the best lobbying talent. Considering the council’s stated policy of “a jury of one’s peers,” I regard this exclusion as a major problem.

As a result of this situation, funding seems to be flowing to fewer and fewer films and to those of a specific type. The trend leans toward conservative (whether patriarchal or feminist), redundant as opposed to innovative, largely big-budget productions that fit into a definite hierarchy, based on the master-apprentice relationship and the applicant’s academic background.

Despite this rather demoralizing context coupled with the presence of government-fed film tyrants (who did their best to discredit our efforts), The Funnel grew in responsibility, complexity and size. Due to constant battles with the Ontario Censor Board and the ever-increasing tasks involved in administering The Funnel’s expanded programs, the bureaucracy grew, resulting in Board member burn-out and committee fatigue. Although The Funnel was ideally structured as a democratic artist-run organization, the process of group decision-making has often resulted in a philosophical split with some favouring a more formal structure and others preferring an atmosphere of greater spontaneity. Amazingly enough, The Funnel has weathered many conflicts, managed to minimize excessive neurotic behaviour, and it at this time fulfilling its original mandate while preparing for the future.

Ironically, I recorded these thoughts having recently moved away from Toronto to New York City. From this vantage point, somewhat removed from the local art wars, it is apparent to me that The Funnel and the work of its members is up there in the international scene. I keep in touch, lend support where I can and look forward to its continued success.

Films to be shown in this series:

I.E. (1976) is a film about making a film, was shot over a two-year period. At the time I thought I was shooting a remake of Man With A Movie Camera but I realize now that although the film is a record of its own making, it is also extremely autobiographical and diaristic.

Crash ‘n’ Burn (1977) was shot in documentary mode. This film is the only surviving filmic artifact of Canada’s first punk club – a Toronto art scene home movie. Creem Magazine praised the film for “doing everything in its flickering power to self destruct… Anyone who thought Canadians bored their beer to death ate at a different delicatessen.”

Sex Without Glasses (1983) is an amalgam of sex without guilt and sight without glasses; the importance of being able to see what you are doing. It is a film about confusing relationships, telephones and wetness, starring a preverbal somnambulist floating between words and objects.