Introduction

There is a visual shorthand I use for each of my friends to keep their celestial heat from turning me into stir fry. There is one I think of only as “that face,” while another has been reduced to a pair of hands always opening. The caption I run under Emily and Cooper is simple enough; they are the future of the couple. While so many dyads use their togetherness as a fortress against the world, bulwarked behind the tragedies of monogamy, Vey Battersduke seem determined to push against every border and boundary until it gives way under their celebration of curiosity.

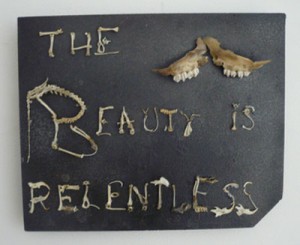

And once they have worked themselves outside of the rules, their newly won vantage offers a pretty good place from which to make art, though this is not a word that comes easily to them. Literature remains the hoped for grail, while art is the disappointed bride that they have decided to embrace. The truth is, they have little patience for most of what passes for video art these days, or any other day, and as a result their post-human offerings are tuned up with a rare and exacting invocation of standards. Imagine an indie pop producer demanding all-night studio sessions for her young charges, take after take, until the new tunes lift at every corner.

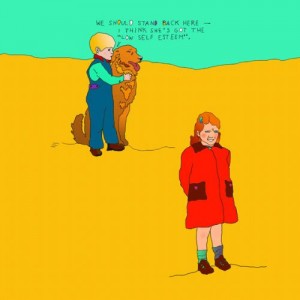

In an art moment frozen in thrall to the sway of conceptualisms, their work is narrative, hummable, humanoid, and invites identification. Hand-drawn cartoons let animal familiars talk to us about children and God and daddy’s porn. Stripped down bedroom pop and home video makeovers jostle with time-lapse compressions unafraid to be beautiful. They don’t proceed with a plan or program; instead, they throw themselves out the windows of their own needs and despairs and wonders, opening their four-armed embrace to homeless island dwellers and feral cats and art mavens. From these close encounters they have created a rare video voice: at once smart and accessible, beautiful and word-wise.

Instead of falling completely in love with Emily, and of course with Cooper—the two are inseparable, in nearly every sense that matters—we began to correspond, to fill up long text fields with characters, most of them unrecognizable as ourselves—and that brought more relief than perhaps it should have. Our notings run well past a hundred pages, and one day it will be the best thing I’ve ever been part of, in the art-world, meta-lingo sense of things, that is. One afternoon she wrote:

“I had a really interesting conversation with my friend Mequitta about the accusation (much flung at me as a younger person) that one is ‘just doing it for attention.’ IT usually being trying to kill one’s self, or cutting, or posting the pages of one’s diary around town. Nobody, for instance, said that Flaubert was just trying to write great novels for attention, or that Jesus was just being the Messiah for attention. Nobody even says (or not much) that Bob Dylan was just writing those folk songs for attention. People did, however, say that Carolee Schneeman was getting naked and rolling around in sausage for attention. People said that Vito Acconci was just making The Red Tapes for attention (specifically Rosalind Krauss said it).”

Two years ago, in a fit of masochism and hope, I proposed to Emily and Cooper that we make a movie together. If we were still without a general public’s attention, then perhaps we could grant this gift to one another. They said sure and I proceeded to blitz the two of them (can a chest hold two hearts?) with one idea after another—uncanny songs, genius quotes, found-footage irresistibles. When is too much too little? They were interested in bonobos, as it turned out, a matriarchal society of nearly vegetarian peacenik apes who have sex often and in every possible combination. We staggered through a year and a half of foreign language mistranslations and pyramid studies before divvying up the pile and heading our separate ways. I worked relentlessly and managed to uncover only new beginnings, while they continued to live every weekend as if it was the last one on the planet and then screamed out a movie with a Sobey deadline pressing on their chests that will be watched for years to come. “So this is what it was like to live in 2010,” some stranger will mutter, wondering that movies could ever have been made, never mind attended, that were flat, and lacking any sense of touch, taste, or smell. Yes, this is what it was like. Welcome to the future of the couple.

I Am a Conjuror: an interview with Emily Vey Duke

Is there nothing they won’t say in front of one another? Is there no terrible infatuation, no secret longing that they cannot share, instantly, as soon as it occurs to either one of them? The foundational vaults of repression that are at the very root of togetherness have been left behind by this dynamic duo whose ongoing domestic adventures provide a glimpse of what couples might look like in the next century. While they wait for the rest of us to catch up they keep busy taking their funny, damaged, wordsmart incarnations out for a walk in video after video. Being Fucked Up (2000), for instance, opens with our heroine huffing crack, singing a song about a perfect nature world, before a cartoon drawing says via voice balloon, “Her soft breast. The sweet, warm milk. Her arms around me. I will punish her for making me wait!” More songs and drawings follow before it concludes with a series of questions which they answer by violently shaking their heads yes or no. Do we need to know more? These bitter sweet episodic tapes might be the latest pop epistle from a shoegazer outfit from Portland, deadpanning their way through another MTV day about getting through their 20s one habit at a time. Instead they have turned to the sometimes rarefied zone of video art and laid their claim, recasting themselves as backwards talking scientists lounging in the bath.

Emily: We hated the idea of betterment, which was used on us like a club—ironic in a solar system whose fundamental principals of design are entropy and decay.

Cooper: So after years of failing to change the things we hated, we decided to change ourselves.

Emily: And now we are conjurors. We can bring anything into existence.

In their apartment (their world), animals know everything, while humans destroy all they touch. Emily will sing in a multi-tracked acapella (if you can’t count on yourself for accompaniment, then who?) while Cooper makes the pictures sing, gathering time lapsed moments from surveillance cameras on the internet (cameras are a last resort he says). Teenaged boys, daddy’s porn (“I hate pornography. It has colonized my orgasm. But here I am, enacting it again”), dope, threesomes, fame, they swing through it with quick epithets in short, scorching scenes.

Mike: There is a myth of how you and Cooper met and fell in together. Could you tell that story?

Emily: OK. When I met Cooper I had been at the Nova Scotia School for Art and Design for a few years. He had moved out East from Kelowna, British Columbia. I was an intensely bitter twenty-one year old. I told Cooper when we met that I thought it was rude of him to crack jokes because some people were so unhappy that they found jokes painfully alienating. I found jokes painfully alienating.

I had seen him a couple of times before. Once he was hitchhiking on the side of the highway and I begged my mom to stop and pick him up. The second time we were on the bus together and I farted, and two really tough girls were on the bus too, and one of them said, “Oh gross! Who farted!” That was horrible.

We finally met at the Khyber which used to be a booze can by night and shitty gallery by day. It was great. I gave Cooper an invite to a show I was having there, and he recognized the style of it, because I had been doing public poster projects in the same style. He told me that he made posters too, and when he described them I was blown away. I had been wondering who had made those posters for so long.

He also told me in the course of this conversation that he was leaving Halifax to go on a hitch-hiking trip for a year in three weeks.

He handed me a little card (photocopied on construction paper) that said “Let’s Dance,” which had a picture of Emmanuel Lewis verso (made by Sandy Plotnikoff, Cooper’s best friend from Kelowna). I didn’t drink and I hated my physicality, so dancing was not my favorite activity. We danced briefly and awkwardly, and then I leaned over to him and said, “Look. I think you’re really cute and interesting and I probably wouldn’t say this if you weren’t leaving.” Then I turned on my nervous heel and walked away, thinking, “He’ll follow me if he likes me too.” He didn’t, and I took the next bus home. I went up to my bedroom and made a poster in what I knew he would recognize as my style. It said, “Wish you said” spray painted on it through a specially made stencil. The next morning I got up and put them all over downtown Halifax (which took about ten minutes).

Cooper saw them and made a response poster. He had been collecting love letters between teenagers for a couple of years, and he put one up next to each one of my wish-you-said posters. It was the most fucking ridiculously romantic thing ever.

So then we went hitchhiking across the US together. Cooper was really mean and kind of humiliated me but I stayed with him. And then I kind of humiliated him, but he stayed with me. Sometimes the unforgivable ought to be forgiven.

Mike: You work and live together, and your art seems to come out of your living. Is there a strict delineation of duties (I write the songs you sing them, I press the buttons, you work the camera…)

Emily: No. Yes. Yes and no. It’s certainly organic, but there are also things we know I will do (like answering email and writing applications and insisting on expressive emotionality in life and work) and things we know Cooper will do (like hooking up the free cable and reading software manuals and, I am ashamed to say, dealing with our finances). We don’t talk a lot about it, nothing is rigid, but we have different strengths and weaknesses.

Okay, I’m not answering any more of these tonight. I’m too tired and I have to shower. But that was fucking awesome. Maybe I’ll just take them one or two at a time. These aren’t questions I can just toss off an answer to. Oh, I’m reading a really amazing book that Shary Boyle sent me called Carrington (a life of Dora Carrington). She was sort of peripheral to the Bloomsbury Group. She was also very fucked up and amazing… She SEEMS like a peripheral figure—like people I’ve known who are amazing artists, but not spotlight seekers—or simultaneously spotlight seekers and shunners. People, I think, like me. Not that I’m peripheral to anything that a book will be written about. Which could be my answer to your question: “Is it painful to be working in a medium where even if you did something show stopping and perfect you couldn’t be famous because no one notices?”

Mike: Do you think that most artists have in them two or three (sometimes it’s more, a limited number anyways) of perfect, necessary things (videos, paintings, books) while the rest is simply place holders, the work you do while waiting for something else to occur?

Emily: Yes, I do think this. I also think, more terrifyingly, that we may ONLY have one or two perfect things that may get wrung out early—the product of an unrecoverable lack of self-consciousness that we continually move away from. Then sometimes I don’t. Sometimes I think I’m just treading water. I also think it’s essential to continue making work (for me, that means to write) even when it feels like I’m dead and making only dead boxes of dry dead death. I think Stephen King reiterated the adage about the muse needing to know where to find you in his book On Writing, something about having to spend a good deal of time at one’s desk.

One of the really painful changes the last few years have brought is a new sense that I have to make new work because it’s my job. It’s expected of me by some infinitesimal (possibly fantasized) public. I think many “professional” artists and writers experience this. It’s probably one of the reasons that we all make, or are tempted to make, work about the trials of making work. That’s what our stupid, smarmy tape The Fine Arts is about. It’s certainly why we make the things that you’ve described as “place-holders.”

I could say something here about the accelerated pace of life in the 20th and 21st centuries putting pressure on artists to produce more faster, but I’ve always been suspicious of the idea that people experienced the world differently in the past. Artists have been driven to madness over the quality and quantity of their work for all of recorded history.

Mike: When I was in film school I found myself surrounded by a group of singularly inarticulate students, language had refused them, and they were looking for another way to say I. Your work by contrast is very literary, beautifully written and performed. Can you talk about the relation of reading/writing and making video?

Emily: As a child I learned to be deeply ashamed of the fact that I didn’t love anything (nature, bicycles, computers, chess) more than I loved talking. I felt incurious about “the way things work.” Because of that lack of curiosity about things other than human intercourse, social and sexual, I despised myself, in large part because it left me vulnerable to being hurt by others—all of whom from time to time would prefer to play soccer or read a handbook of some kind rather than talk about our “relationship.” It left me “needy,” which is in my opinion the most pejorative descriptor in the English language.

I have been able to achieve a modicum of self-love through my intense curiosity about language. I love words. I love The Elements of Style by Strunk and White. I love the Miriam-Webster Word of the Day. If I could only have one book in the world, it would be a really excellent dictionary. The Complete Oxford. Many volumes. Etymological.

Right now I am working on a project of writing a series of plot synopses. I love the words, yes, but that’s a poet’s minefield. I’ve always been short on plot. This project is about packing the humanity, the identification and emotional immediacy I always strive for, into a form which is both more conventional and more challenging than my autobiographical default. Autobiography is like a reflex for me. It’s beginning to feel too self-indulgent and precious. It’s time to try something new. But then, is that drive (to “grow” or “progress” as a maker) even more self-indulgent? The reader doesn’t care if I’m being formally redundant. Or do they? Who is the reader? I’m meandering.

Mike: Steve Reinke has been a teacher for you in two cities now, can you talk about what he’s meant for your work? Is it necessary to kill the father? How would you kill Steve?

Emily: Steve’s work is too coy, clever and sadistic. Sometimes he lacks the perfectionism necessary to make the tapes stand out from the sea of mediocrity that is contemporary film/video. That is how I kill him.

I also kill him by loving him and wanting to protect instead of exceed him. And yes, he is me and Cooper’s beloved Dad, and every animal we kill we drag back to him for his approval.

Mike: Is it important to know tradition, what’s been done in the field, and other fields, in order to make your own work? Do you suffer from ‘anxieties of influence?’

Emily: I think (and this is so obvious it barely merits writing) that it is both a blessing and a curse. It can be crippling to know what’s already been done. If I had known the fucking banquet of backwards delights being brewed up at roughly the same time as I am a Conjuror and Attention Public, we probably wouldn’t have made them. However, seeing truly excellent artists like Miranda July and Eija-Liisa Ahtila inspires me to press on, to make works that are not the shit I usually see at festivals and screenings.

Mike: Can you talk about talking backwards? It’s a structuring mechanism you use in several of your tapes, all of which feature you and Cooper. Why backwards?

Emily: Nobody wants to hear this, but it truly is just a device to compensate for the fact that we are terrible actors. After we used it the first time we of course started to question what meanings and connotations it held and how we could potentially exploit them. It worked so we stuck with it.

Mike: Do you ever feel that you’ve shown too much? When you’re smoking crack in Being Fucked Up, or dancing naked, or describing your threesome livings or socking Cooper in the face. How do you give yourself permission to show and share these moments?

Emily: I feel that others think I’ve shown too much. For me, it’s like my certification to be fucked up in life. Sometimes I feel that it’s a professional liability, but I cling to it as a badge, as a line-marker: I will not be totally obedient to the conventions of public and private. Honestly, my very sick fantasy is that if I make my private self public I can be absolved for my manifold sins.

Mike: Is art an indulgence, a luxury, an extra? People are starving in the world, AIDS is rampant, wars are brewing, Palestinians are being slaughtered by Israeli teenagers dressed up as soldiers, the American empire continues to pillage. What does making art mean in the face of this?

Emily: This may be my biggest concern as an artist. I think about it constantly and have no answer. It’s been thrown into high relief by the fact that my little brother Peter has just returned from a year doing aid work in Sierra Leone. Another project I’m working on right now is a collaboration with him based on the fucking astonishing journal he wrote while he was there. He’s so pragmatic about it, and I know that he feels, (as I did about my Khyber “art” job), that while the work might be noble in some sort of Platonic Ideal sense, the reality is pretty mundane and ineffectual.

Part of the way I’ve been thinking about this: the greatest pain I’ve ever experienced is the pain of romantic rejection. This pain was great enough to hospitalize me for over a month after a youthful (but serious) suicide attempt. It was also my impetus to “find my voice” and make art.

I thought that anyone who didn’t share my suffering was either an idiot or in denial. It was all very clear: women were destined to live a life of intolerable psychic agony because our romantic impulse was unmatched by men. Men fear entrapment; women fear abandonment. I was certain of these truths in the way that only a person with extraordinarily narrow experience can be certain.

There was no room in my model for the suffering felt by child-soldiers who were forced to rape their own mother and then kill her and the rest of their families, for slaughtered or exiled activists, for people who had their lips and limbs hacked off with an axe, for people who watched their houses and families swept away by weather, for people who endured torture, for people who watched everyone they loved, everyone who accepted them, die of AIDS. Those things were too important to have any relevance to me, if that makes sense. When I saw artworks that took as their subject the great injustices of the world, I thought something like “Oh, issues art. Bo-ring. Who CARES about people being disappeared in Chile. Nobody really cares about that. Why don’t they make work about what they really care about, like how much it hurts to be rejected.”

My pain, which felt uncontrollable and huge, is petty. My art, which I made with the great urgency I felt about expressing that pain, about reaching out, is petty. And yet that isn’t the end of me speaking. That isn’t the end of my voice. Maybe it should be, but for whatever ridiculous reasons, it isn’t.

Mike: What is the compulsion to keep working? Isn’t what you’ve made enough? Does there have to be more, should there be more?

Emily: Maybe we make more because we think eventually we will make something that helps. Or because of capitalism. Or because we think we’ll get famous. Or because it’s the only thing we believe in about ourselves.

Mike: Video is a medium which has nothing essential in it, reel to reel, 3/4″, high-8, one chip digital, three chip digital, betacam, it’s always giving way to the new so quickly. Do you worry what you make won’t be showable in any way in a few decades?

Emily: No. I think if the work is strong enough that people continue to want to see it, it will continue to be remastered. If it languishes on the shelf it’s because people no longer find it interesting. I hope our works don’t get remastered just because some place like Video Out gets a Canada Council grant to create a climate controlled archive where every tape in their library will exist for perpetuity etched on special diamond chips that you can plug into your personal entertainment videophone day planner goggles. That would be depressing. Nobody would ever choose to plug Being Fucked Up into their goggles! They could be watching the female ejaculation Olympics or the new reality TV show about psychopaths where the winning psychopath gets out of jail but has to have cameras embedded in his eyeballs so we can be with him (or her, that would be really good. A child would be really good too) when he goes on his next rape and murder spree.

Mike: Why did you move to Chicago?

Emily: To go to graduate school, and because Steve asked us to. Chicago was totally irrelevant to us before we went there. It’s possible that in seven years of being together Cooper and I had never ever said the word Chicago to one another. Still, R Kelly is from there—you know, the one whose lawyer said, “The bank of R Kelly is now closed,” when Kelly was faced with yet another statutory rape charge, this one involving Kelly urinating on a 14 year old girl. Still, the Ignition Remix was THE song that summer, with lyrics like “Girl I’m feelin what you’re feelin, no more hopin’ and wishin’. I’m about to take my key and stick it in the ignition.” The record label told Kelly he couldn’t say “your ignition” because it was too suggestive.

When we went to Chicago Cooper and I were both like, “Chicago, whatever.” But when we got there it took about ten seconds before we were like, “Holy shit. Chicago! I’ve heard of O’Hare airport before and now I just flew into it! It’s like being famous!”

The proximity to fame—famous people and places, famous architecture and public art and bridges and stuff—is one of the most interesting things about going to the US for me. Even if I was in Fucktown, Ohio or Suckyberg, Kansas, I felt like everything I looked at was famous—the way a waitress put a glass down on the table, the big flaccid families scarfing down big flaccid food. Maybe I’m just describing the experience of the exotic, but the way in which America is exotic to Canadians has something to do with the proximity to, and hence the possibility of, fame. That would be the worst part of it. The constant, vague pressure to do more, be better, be prettier, be ready to pounce when the opportunity comes. It’s bad enough here, where it’s a pipedream most people outgrow as soon as they’re old enough to distinguish between us (reasonable, earnest, frumpy) and them (grandiose, boorish, fabulous).

Mike: Why did you move away from Chicago?

Emily: Because we were scrambling for money and it looked like a hard year ahead. Then I got the Khyber Art Gallery job, which offered security and a perverse symmetry to my life: returning to the centre on its tenth birthday which coincided with the tenth anniversary of Cooper and I meeting and falling in love there. And because I never, ever felt at home in the US. I always felt like a spectator, like the people I was meeting and becoming friends with would only be part of my life for a short time. As soon as I got back to Canada that feeling went away and the opposite took its place: “These are the people I will be seeing at art events in Canada for the rest of my life, and I love them. Grudges will wax and wane, slights and sex will scald and be forgotten. We’re home.”

Mike: Is it difficult to look at yourself in your own work? Of course you’re both very young, but the tapes are a record of your aging, amongst other things. Is it hard looking at yourself as a thing made of pixels?

Emily: To answer this question I have to explain something complicated. Actually, it’s not that complicated—it’s just been described so often and misunderstood so completely that I need to be precise. The way it’s usually talked about centers around the word “objectification.” I remember hearing that word as a teenage girl and thinking, “That makes no sense. Objectification! What on earth could that mean? I don’t feel like an object, like a table or a car!” I guess my understanding was too literal. When I was in university it shifted from being a totally foreign, irritating concept to being the perfect word to describe how I had felt all my life. It was about women being objects to look at and desire, not functional objects. Not objects like skill saws. Objects like flowers. Objects like antiques. Objects like children. It wasn’t that women (or children) weren’t understood as having interiority either—interiority was on display too. Our insides also had to be desirable. Because we were there to be evaluated, and the thing that determined my rank was how much desire and tenderness I could evoke. And that was incredibly painful for me, because I knew that my insides were not desirable and would not evoke tenderness. I was bad and a liar and self-interested. And my outside wasn’t desirable either, not until I became an anorexic fashion plate doing cumbersome, soul-crushing drag. But in my formative years I was a little fatty, and inside I am still a fatty.

Becoming thin on the outside was an act of feminist terrorism for me. I know now that it was a bad strategy, that it failed to bring me the results I wanted, but rage was my impetus. I wanted to pay “men” back for subjecting me to their painful evaluation (and especially for communicating to me that I failed to meet their standards of beauty and goodness). I thought I could do that by making myself desirable and then rejecting them. It didn’t work.

It’s harder for me to stay away from the camera than it is for me to perform because there has never been a moment of my life, not for as long as I can remember, that I haven’t been imagining someone was watching. One of my first memories of this is when I was about eight years old. We were at my grandparents’ cottage in St Margaret’s Bay, and I was off by myself in a field full of wildflowers. It was a perfect summer day. I remember throwing my hands up and spinning around and around until I fell down, thinking, “If only someone was watching me right now, then I would be happy. I’m sure I look beautiful now. I’m sure I look innocent and good.”

Mike: Is showing work part of its making (its completion)? Could you make work and not show it?

Emily: I don’t know if I would describe showing the work as a part of the process of making it. It’s the reason I make work, to create mutual human feeling.

As for the question of whether I would keep making stuff if I couldn’t show it or had taken some kind of vow against showing it, I’m not certain. People often talk about the concept of “creativity” in art. They say things like, “So you’re an artist? You must be very creative”, or “My daughter has a really good art teacher. She really brings out the students’ creativity.” I’ve always been baffled by this term. I remember having what was called a “creativity test” when I was in grade six. I thought, “Oh good. I like art and I write poems, I should be good at this.” We had to take out a piece of paper and a pencil, and the teacher said, “Okay, now I want you to make a line in any direction. Any direction at all.” I made a diagonal line toward the upper left corner of the page. I waited for the next instruction. My teacher said, “Alright, that’s it. Keep your pencils right where they are. I see we only have one creative student in this class!” She pointed at a boy whose pencil was suspended in the air above his page.

Making my work has absolutely nothing to do with that kind of creativity, which is for computer programmers and physicists. My work is about communication. If the work no longer had the possibility of an audience, I would stop making art with that aim. I would definitely stop making videos. But I think I would start to use my “creativity” more, because it would be fun and useful to solve problems and invent diversions for myself.

Mike: Was it ever difficult to think of yourself as an artist? What did your parents think?

Emily: When I was about eleven I asked my mom if she would be upset if I was gay. She told me no, that she would love me just as much if I was gay, but that she would worry that my life would be harder. I wish she had had the same foresight about my decision to be an artist. Instead she just encouraged me to follow my interest in art and writing.

We have artists in my family, so it was never a very big deal for me to think of myself that way. It didn’t seem to denote any special status—my uncle had been an artist all my life, and he was still living in a draughty garage and doing occasional stints as a cook. He was, however, incredibly cool—probably the coolest person I knew—and I was totally preoccupied with being cool, especially after I graduated from high school.

Mike: Do people fall in love with you after seeing your work? Is art the prelude to love (or is love the prelude to art?)

Emily: People don’t fall in love with me, but it does make some people see me as more powerful and desirable than I really am. I’m certain that it makes other people write me off completely, either before or after they’ve met me, but those people are much less likely to approach. It’s a strange thing about being an artist (or a performer, a writer—or maybe just a human). We mostly hear the positive things people have to say about our performance in the world.

If I am completely honest, however, I have to confess that my drive to make work is essentially the same as my drive to make people fall in love with me. I have a kind of emotional disorder that makes me want everyone in the world to be in love with me. It’s a very destructive part of my personality (destructive to myself and to others), and I use my moral energies to fight it back.

Mike: Your work is very accessible, but it’s not TV or feature films. Why don’t you make work that formats into available accessible genre formats in order to reach a larger audience?

Emily: This is a question I ask myself again and again. The answer isn’t straightforward, it’s kind of like saying, “You’re a Canadian proctologist, but they need a lot of urologists in India. Why don’t you become an Indian urologist?” I work in video art, an incredibly (and rightfully) obscure world where the bar is low. I don’t like watching most video art. If I had a big library of video art tapes (which I do) and a TV/VCR (which I do), I would watch TV. I wouldn’t watch the art videos. In fact, I’m half watching TV right now. King of the Hill. And the reception is absolutely awful.

So why do I stay in this world? For a few reasons. The first and most significant is that I am simply not talented enough to work in television. I couldn’t, for instance, write for a situation comedy. My humourous insights are few and far between.

The second is that my parents totally discouraged me from my first passion, which was acting. From the age of four until I was in my early teens, I was dead set on being a Broadway star. As a little girl I collected soundtracks from musicals: My Fair Lady, Oklahoma, The Sound of Music, South Pacific and so on. Fame was my favorite TV show. Danny Amatullo was one of my last true sexual passions. I wanted to go to school at the Fame school. Then one night, when I had been sent to my room for being bad in some way or another, I heard my parents talking about me downstairs. I snuck to the top of the steps so I could listen to them, and I heard my mother say something like, “Jim, I’m just so worried about what Emily is going to do with her life! She’s so set on this acting and singing thing, but I really don’t think her voice is that good! And she’s so terrible at math.” I went into my room and cried, and then I made up some math questions and brought the answers down to show them. But that’s an extreme example. Mostly they just subtly communicated to me that it wasn’t feasible. My mom said things like, “Do you know how many little girls want to be stars on Broadway, Emily?” Also, I was never given a speaking part in any of our elementary school musicals. They always went to the perfect blonde popular girls, especially Christy and Karen MacDonald, the identical twins with blonde ringlets whose mother made them drink whole milk because they were so thin. I was a fat little social pariah, and my music teacher, who cast the musicals, found me repugnant. In grade three I boycotted. I auditioned, and when the list was posted on the music room door I fought my fat little way to the front only to discover that I had been cast as an extra in the tea-party scene. I was absolutely devastated. I think that’s when I gave up on the idea of being a famous performer in the mainstream media. Maybe if I had grown up in New York or LA it would have been different, but I think the only real change would have been in scale—I would still have been a fat little pariah, but Christy and Karen would have had their own sit-coms.

Finally, I think film and television are nothing more than the poisonous tentacles of the free market, configuring our desire in perverted and devastating ways.

Mike: Can you talk about the role of animals in your work?

Emily: Animals, like children, are a repository for all our fantasies about innocence and simplicity. Animals can be forgiven for things that we would despise a human for. Imagine how irritating it would be if Cooper and I had performed the dialogue between the otter and the muskrat in Curious About Existence, where one of them quotes Nietzsche to the other. It would seem insufferably pretentious. Put the same words into the mouths of animals (or children) and it’s funny and charming.

Mike: Are drugs good for creativity?

Emily: The term “drugs” describes a vast territory, but I’ll assume that you’re referring here to illicit or recreational drugs. Certain illicit drugs may be good for creativity, but addiction is unquestionably not.

I’m more interested right now in the effect that selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors and other neuro-active “mood brighteners” have on creativity. I’m talking about drugs like Paxil, Prozac, Wellbutrin, and Selexa. These drugs fascinate me. They are prescribed very widely, in large part because they are thought to be non-addictive (although when people stop taking these drugs cold-turkey, they describe horrible withdrawal symptoms), and they have complex and poorly understood effects on personality.

I’ve been on Selexa for about two and a half years, and I spend a lot of time thinking about which changes in my life and my work are attributable to the drug. For instance, I have felt a loss of urgency around making and exhibiting my work over that period of time. Is this a side effect of the drug or just an effect of getting older? Also during that span of time I became an alcoholic. My alcoholism was never particularly distressing for me. I didn’t feel the guilt I used to feel after drinking. I regretted the stupid things I did while drunk, but I eventually resolved that problem by only drinking at home. I finally stopped when other drugs re-emerged as a problem, and I recognized that alcohol was a gateway drug. Once I decided to stop drinking, I noticed something for the first time: I had been working so hard at achieving oblivion that I had essentially missed a year of my life. Did I become an alcoholic because the drug freed me from remorse or because I had a dreadful Artist Run Centre job and a houseguest who wouldn’t leave?

It’s such a terrible cliché, but I can’t help but wonder if suffering is a crucial part of my practice as an artist. I mean it’s not like I don’t suffer since I started taking anti-depressants. I still suffer, but much less. I used to feel such intense despair that I became hysterical. I don’t become hysterical any more. Maybe I was more interesting when my moods were more extreme. Maybe I had to feel those things to be able to write about them with passion. I have little interest in describing my emotional landscape now. I’m inclined instead to write about other people or natural phenomena. Worse, I fear that I wouldn’t like to consume my newer work, the work I’ve made while I’ve been on Selexa, as much as I would like to consume the work that came before.

Videos

Rapt and Happy 17 minutes 1999

Here are the vid kids of Steve Reinke: wordwise, sexy, unafraid to wear their pop on their sleeve, and funny, but not in a clamouring slapsticked fashion. Set in 16 parts, Rapt is disarmingly fresh, smelling of the long summer in which it was made. Catfights, threesomes and daddy’s porn emerge in videobyte succession, as this duo turn intimacy into playtime. Early fave for rookie of the year honours.

My Heart the Lumberjack 13 seconds 2000

This is part of a series begun by the handsome Montreal video artist Nelson Henricks. Each work in the series has the words, “My Heart the…” in the title. For their star turn, the dynamic duo simply excise a television moment where an overzealous suitor approaches a woman, opens her black leather jacket and announces, “Look at you, look at this little body. I’m telling you, you’re so small I’m going to split you like wet pine.”

Being Fucked Up 10 minutes 2001

Why not open proceedings with a nice long crack toot, and then hold up the bag in front of that impossibly young and serious face, with its boyish haircut and the schoolkid shirt collar, and breathe all the fairy dust into the plastic lung of the bag and suck it all back in again? I’m a self contained system, I’m the whole fucking world, watch me fly. Being Fucked Up is an abject hymn of drugs, sex, and self loathing; it’s a dog’s life alright, but somehow the artists serve it up with such charm and home made invention that I want to sing along. Each scene is answered by a cartoon dog interlude, usually dished in brief monologues that are horny, funny and self centered. The answering shots deliver a pair of portrait moments: an extended nightvision shot of the artist’s ass is accompanied by a song promising punishment and grace, while in another, Emily tries on an extra pair of lips while Cooper’s voice-over lampoons the possibility of salvation. The bravura sequence is entitled Monologue For Robots which offers still photograph snaps of the artists at play – wasted youth moments and sex posings offer glimpses of unraveling lives as a computer voice bleats, “My secrets are so boring.” The movie closes with a set of questions that the artists answer by shaking their heads vigorously yes or no. It’s good if you can survive it, if you can get as far as the door, the morning after, the next step. And if it only feels good for the audience, that’s ok too. Call it another kick, another way to get high. Nothing lasts except the promise of next time.

The Fine Arts 3 minutes 2001

This performance brief features Emily’s topless performance lecture about art about art. In French. There is some kind of equivalence between the halting French speech and her breasts which stare back at the viewer in mute accusation. She talks about her talking in a send up of conceptual art, which she despises by embracing. “This is not a good idea. Maybe with sunglasses it’s a good idea. Maybe not. No.”

Perfect Nature World 3.5 minutes 2002 (collaboration with Shary Boyle)

Lifting the opening song from Being Fucked Up, Emily’s multi-tracked voicings (“I don’t know, I don’t know”) are this time laid over a series of drawings by Toronto’s multi-media work dervish Shary Boyle. A seamless pan offers glimpses of a bruised and lonely pre-teen heroine who gathers her lost hopes between nature world communings. Sometimes the sparkles stick to you even when you’re sleeping in the puddles.

Bad Ideas for Paradise 20 minutes 2001

Like all of their best work, Paradise hangs on a series of apparently unrelated monologues, lacerating in their social critique and abject humour, and delivered in a series of carefully composed vignettes, with careful attention paid to the video delivery vehiclea. Here the monologues appear as glowing title screens, singsongs, sped up voice-overs across found footage and night vision lurches. Topics include shame, boredom, childhood and what animals care about. But the centerpiece is a three minute hilarity called I Want To Be A Teenage Boy. “Brain chemicals flood, orifices gape. I fart with vigour. It feels great. I hate homos. I like boobs, my dick, my friends, smoking dope and listening to music. Unselfconsciousness and arrogance are the hallmarks of my personality. I am unconcerned by my ordinariness. I am unconcerned in general.” Proceeding via bon mot stepping stones, Paradise rubs its new age-isms (gems, heart chakras, yoga) into a wordly and wondering suite of persona failures with relentless indie pop charm.

Curious About Existence 11 minutes 2003

This movie is Emily and Cooper-lite, as if they were breathing with one lung between the two of them. It is framed by a pair of opening and closing songs about creating a world out of the body, and a body out of the world. In between are a pair of philosophical conversations. The first turns to Newton’s laws to recast despairing emotions as part of a chain of energetic transfers and interdependence. The second is a dialogue between an otter and a marmot about feeling bad. Nietzsche’s counsel to Wagner’s wife is offered as a remedy… “that which you take into your mouth you may develop a taste for.” Her reply is more radical still, insisting, like the opening song, that observer and observed are cut from the same cloth, that the self is empty and illusory. As Stephen Batchelor writes, “We are our own jailors. We keep ourselves unfree by clinging, out of confusion and fear, to a self that exists independently of all conditions. Instead of accepting and understanding things as they are, we seek independence from them in the fiction of an isolated selfhood. Ironically, this alienated self-centredness is then confused with individual freedom.”

The New Freedom Founders 26 minutes 2005

This is sometimes shown as three separate movies, and sometimes as a three screen gallery confection, and more occasionally as a single movie. In the first episode, I Am a Conjuror, the artists pose as layabout scientists, sleeping in, bathtubbing and drinking, while they murmur backwards philosophy that is rendered in subtitles. It’s uncanny the way they are able to conjure narrativity in these few simple, static, home movie frames. They appear as avant garde scientists who are about to plant a Nobel on their mantel for a paradigm shifting medical discovery that will drive multinational giants like Pfizer out of business. They are transitional figures appearing “before the reconstruction,” when the animals and outlawed (or simply forgotten) marginal thinkers and artists, will come back to rebuild the planet.

In the second episode, A Cure for Being Ordinary (aka Rafters), Cooper dishes a slightly sped up, high pitched monologue, lensed from two or three alternating vantages, about the worshiping of time, and his employment history at Harvey’s and the Scotia Bank.

In the final episode, Attention Public, Emily reappears as a red clad backwards singer, narrating the story of her underground life where she creates a “new freedom language.” An experimental centre is established in Halifax where a (boring and hard) elite explore ‘p e’ space. They decide to bring their language above ground but press conferences fail, so they decide to record a video message that can be sent directly to the public. Of course, that message is also the tape we are watching. A send up of avant-garde, navel-gazing isolationisms and religious cult practices, Attention Public manages a final sleight of hand by framing the whole talk within a pair of domestic, badly made bumpers. This is how the revolution will be televised: from someone’s living room, in a language so personal that no one will be able to understand unless you’re already hipped to the code.

Songs of Praise for the Heart Beyond Cure 15 minutes 2006

A Christian scribe named Jeremiah wrote: “The heart is deceitful above all things and beyond cure. Who can understand it?” Emily and Cooper lean into this question with a nine part musing filled with global surveillance time lapses, mirrored-screen landscape moments, breathing cityscapes, a stunning digital pan over a frozen forest stuffed with birds, and a chatterbox high school moralist. The hand made animations of their previous efforts return here in brightly coloured monologue vignettes, sometimes subtitled because wizards tend to speak backwards. While everything human turns to humiliation and shame (survival is the best we can hope for), the animal world offers alternate social modeling and the balm of beauty. They are the song.

Sometimes Numa Numa Makes You Cry 2:30 minutes 2006

The Romanian/Moldavian band O-Zone released a number called Dragostea Din Tei, that is sometimes named as their second best tune. But it didn’t blow up until Gary Brolsma’s released it as Numa Numa, featuring who else but himself lipsynching with traditional Youtubed overzealousness. It went viral, and is (at the time of this writing) the second most watched vid of all time, gathering 700 million views. The artists offer a multi-screen remix with English and Romanian subtitles so we can sing along. Their remake closes with a wincing solo performance from a TV program named “Superstar,” by a young blonde man whose dreams are eight sizes larger than his talent. But wait. Are those tears underneath all that teen cheer?

Beauty Plus Pity 15 minutes 2009

Punctuated with nature beautiful pics showing sunlit deer being patiently tracked by smiling Norwegian hunters, Beauty offers an answering call of animations that voice animal longings. The hunters are dished in a computer driven muse that spreads like an oil slick over pictures of children and zoo animals. Between these two poles are God and the family, though the Old Testament hero appears here like Santa Claus on a diet, complete with red blazer and unkempt beard. He is not incidentally senile, out of touch, medicated, and wasting his magic on pretenders. The voices of dissent appear as a cappella numbers sung over primary coloured landscapes and melting portrait poses, including a winning riff on Philip Larkin’s well known ode to family “They Fuck You Up.” As the movie hopscotches between found footage hunting rites and animated asides, it is trying to dig in somewhere and find roots. Where is the larger design in all this, the promised relief of order? Children and animals are held out and then withdrawn as possible saviour portals. And in the absence of the divine, we are busy killing animals. Families, of course, are the incubators of these killers. “We all love children. We love them not because they are good, which they are not, but because, unlike adults, they can claim the potential to become good.” How can a movie filled with so much despair feel so fine?

Lesser Apes 14 minutes 2010

While this movie went through several bravura versions in its inaugural year, its final deadline call has smoothed out the asides and diary trajectories and refashioned it as the closest thing to narrative the dynamic duo have yet managed. Farrah, a primatologist by trade, falls in love with her object of study, the female bonobo Meema. At last the unfulfilled promise of sex arrives via interspecies love. Propelled by three lengthy voice-over sessions, Lesser Apes slowly but surely turns toward questions of the law, the moral codes and legislatures that lie in and outside the body. The sexual revolution is led by self-named “perverts,” though it is striking just how often animals—human and ape alike—appear quite alone. The movie closes with a suite of lush diary throwaways: a bedazzled cat in the forest, corpses twitching, a scarred arm resting on the remains of a drink. A bilingual song quietly echoes that the singer would like to impart a moral lesson, but doesn’t know where to look for it. Oh well.