- Sharits obit (pdf)

- Sharits by Yann Beauvais (pdf)

- Sharits by Stuart Liebman (pdf)

- Paul Sharits bio

- Notes on Films by Paul Sharits (1969)

- Obituary (1993)

- Postscript as Preface by Paul Sharits (January 1973)

- Red, Blue, Godard by Paul Sharits (1966)

- Mental Funerals: an interview with Paul Sharits by John Du Cane and Simon Field (London, 1970)

- Words Per Page by Paul Sharits (1970)

- Paul Sharits: Illusion and Object by Regina Cornwell (1971)

- A Cinematics Model for Film Studies in Higher Education by Paul Sharits (September 1974)

- Regarding the “Frozen Film Frame” Series: A Statement for the 5th International Experimental Film Festival, Knokke by Paul Sharits (December 1974)

- Program note for the Whitney Museum of American Art’s New American Film Series by Paul Sharits (January 1975)

- Cinema as Cognition: Introductory Remarks by Paul Sharits (August 1975)

- Statement Regarding Multiple Screen/Sound “Locational” Film Environments – Installations by Paul Sharits (1976)

- Paul Sharits interview with Gerald O’Grady (1976)

- Paul Sharits by Rosalind Krauss (1976)

- Hearing : Seeing by Paul Sharits (1976)

- An Interview with Paul Sharits by Linda Cathcart (1976)

- My painting (& film) for Galerie A by Paul Sharits

- Apparent Motion and Film Structure: Paul Sharits’s Shutter Interface by Stuart Liebman (1978)

- Paul Sharits Tribute in Baltimore (2004)

- Paul Sharits by Kristin M. Jones (2009)

- The Avant and the New by Martin Rumsby (2009)

- Paul Sharits films

Paul Sharits bio

Paul Sharits bio

Sharits negates filmic illusion, and places the focus on the function and materiality of film, as well as on the viewers’ subjective perception. In N:O:T:H:I:N:G [1968] or T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G [1968] he replaced the earlier »color fields« with associative images, and thereby extended the reduced »flicker film« concept. Increasingly the sound track also developed into an equally important, rhythmic and independent element within his films. Later works focus more strongly on the physical materiality of the film strip, in as much as it is worked over, scratched, and damaged. In 3rd Degree [1982] Sharits associated the fragility of filmic material with the vulnerability of the human body.

The Frozen Film Frames [1960s-70s] are serial arrangements of film strips, which- like the sketchy Scores – visualize film’s overall structure. With the Locational Film Pieces [beginning in 1971, among them Epileptic Seizure Comparison of 1976], Sharits shifted from the context of a frontally oriented movie theatre into the gallery space, and extended reception possibilities via its open structure and the interactive play between various synchronicities. Sharits has documented filmic thinking not just in films and film installations, but also in excellent theoretical writings. His installations with multiple projections have not just extended filmic time and space, but rather pictorial space in a general sense, including that of painting. As a member of the Fluxus movement in New York, he also produced objects and performances of a profound expressiveness.

Within a non-hierarchical juxtaposition, Sharits investigated the most varied means of representation, extending from film to painting. At the beginning of the 1980s, abstract but also expressionistic image backgrounds with figurative elements were produced. Frequently he took up motifs or ideas again, moved them from one medium into the next, and made thinking’s circulating process itself into a focus of attention. Paul Sharits taught from 1973 until his death in 1993 in the Department of Media Study at SUNY, Buffalo.

“What has taken us time to fully grasp and then aesthetically accommodate is the radicality of the break Sharits made. He had abandoned painting by the mid-’60s, seeing in film a practice that provided a greater range of philosophical and aesthetic registers. In short order, he created a series of canonical 16-mm works exploiting the flicker effect, including Word Movie/Fluxfilm 29 (1966), N:O:T:H:I:N:G (1968), and T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G (1968). His subsequent shift to installation—what he termed “locational film pieces”—returned his work to the gallery and brought “the act of presenting and viewing a film as close as possible to the conditions of hanging and looking at painting.” What made these works manifestly ready for the white cube was in part his singular rejection of film’s representational content, its traditional reliance on mimesis and language, and in part his willingness to take the technology in hand and refashion it for his own needs. He composed his films using color-coded scores and fabricated them from nonobjective sources. His deployment of the standard apparatus for exhibition—the motion-picture projector—required an alteration of the transport and shutter mechanisms. For his first locational piece, Sound Strip/Film Strip, 1971, Sharits shifted the standard aspect ratio of film by projecting the images sideways, and for Shutter Interface he serially aligned the projectors in a manner that critic Rosalind Krauss described at the time as “muraliz[ing] the field of projection.” Even the visible presence of the projectors—a taboo for nearly all forms of cinema, from commercial to avant-garde—created what Krauss termed a “sculptural” presence and revealed “the work’s involvement in its own material basis.” Bruce Jenkins on Paul Sharits, ‘Out of the Dark,’ Artforum (2009)

An excellent book about Paul Sharits was edited by Yann Beauvais.

You can find out more about it, and order it here: http://www.lespressesdureel.com/EN/ouvrage.php?id=1118

You can visit his website here: http://www.paulsharits.com

Eight films and the Gerald O’Grady interview are available for preview at Ubuweb.

(Sears Catalogue 1-3 (1965), Dots 1&2 (1965), Wirst Trick (1965), Unrolling Event (1965), Word Movie(1966), Epileptic Seizure Comparison (1976), Tails (1976), Bad Burns (1982))

http://www.ubu.com/

Another excellent book containing vital Paul Sharits info is:

Buffalo Heads

Media Study, Media Practice, Media Pioneers, 1973-1990

Edited by Woody Vasulka and Peter Weibel

Art by James Blue, Tony Conrad, Hollis Frampton, Gerald O’Grady, Paul Sharits, Steina, Woody Vasulka and Peter Weibel

You can order it here: http://mitpress.mit.edu/catalog/item/default.asp?ttype=2&tid=11304

Notes on Films by Paul Sharits (1969)

Notes on Films/1966-68 by Paul Sharits

Film Culture 47, Summer 1969, p.13-16.

(OVERTURE: “All writing is pigshit. People who leave the obscure and try to define whatever it is that goes on in their heads, are pigs.” Antonin Artaud)

GENERAL STATEMENT FOR 4th INTERNATIONAL EXPERIMENTAL FILM FESTIVAL, KNOKKE-LE ZOUTE: I am tempted to use this occasion to say nothing at all and simply let my films function as the carriers of themselves – except that this would be perhaps too arrogant and, more important, a good deal of my art does not, in fact, “contain itself.” It is difficult for me to verbalize about “my intentions” not only because the films are non-verbal experiences but because they are structured so as to demand more of viewers than attention and appreciation; that is, these works require a certain fusion of “my intentions” and with the “viewer’s intentions.”

This has nothing to do with “pleasing an audience” – I mean to say that in my cinema flashes of projected light initiate neural transmission as much as they are analogues of such transmission systems and that the human retina is as much a “movie screen” as is the screen proper. At the risk of sounding immodest, by re-examining the basic mechanisms of motion pictures and by making these fundamentals explicitly concrete, I am working toward a completely new conception of cinema. Traditionally, “abstract films,” because they are extensions of the aesthetics and pictorial principles of painting or are simply demonstrations of optics, are no more cinematic than narrative-dramatic films which squeeze literature and theatre onto a two-dimensional screen. I wish to abandon imitation and illusion and enter directly into the higher drama of: celluloid, two-dimensional strips; individual rectangular frames; the nature of sprockets and emulsion; projector operations; the three-dimensional light beam; environmental illumination; the two-dimensional reflective screen surface; the retinal screen; optic nerve and individual psycho-physical subjectivities and consciousness. In this cinematic drama, light is energy rather than a tool for the representation of non-filmic objects, shapes and textures. Given the fact of retinal inertia and the flickering shutter mechanism of film projection, one may generate virtual forms, create actual motion (rather than illustrate it), build actual color-space (rather than picture it), and be involved in actual time (immediate presence).

While my films have thematic structures (such as the sense of striving, leading to mental suicide and death, and then rhythms of rebirth in Ray Gun Virus and the viability of sexual dynamics as an alternative to destructive violence in Piece Mandala End War), they are not at all stories. I think of my present work as being occasions for meditational-visionary experience.

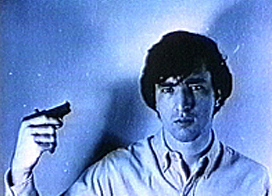

RAY GUN VIRUS/SYNOPSIS FOR 4th INTERNATIONAL EXPERIMENTAL FILM FESTIVAL COMPETITION: The film was made to induce the sense of a consciousness which destroys itself by linear striving, fixated on achieving the “blueness” of inner vision yet caught up, by that very intention, in obsessive cycles – consciousness hung up in patterns external and in opposition to its own structure. Weakened by its own aggressiveness, infection sets in; progressive vicious cycles of decay amount to a self-induced death, a mental suicide. Through the blank darkness, consciousness is freed to turn inward upon itself and is reborn on its own organic terms. The film does what it is. Non-filmic images and stories are not allowed to interfere with the viewers’ awareness of the immediate reality while experiencing the film. Light-color-energy patterns generate internal time-shape and allow the viewer to become aware of the electrical-chemical functioning of his own nervous system. Just as the “film’s consciousness” becomes infected, so also does the viewers’: the projector is an audio-visual pistol; the screen looks at the audience; the retina screen is a target. Goal: the temporary assassination of the viewers’ normative consciousness. The film’s final “image” is a faint blue (attached by not striving for it) and the viewer is left to his own reconstruction of self, left with a screen upon which his retina may project its own patterns.

PIECE MANDALA/END WAR/SYNOPSIS FOR 4th INTERNATIONAL EXPERIMENTAL FILM FESTIVAL COMPETITION: This work was made for an anthology of films the general theme of which was to be For Life, Against The War; the film was not completed in time to be eligible for inclusion in that anthology and thus stands on its own as a statement of that theme. Piece Mandala is not narrative drama; instead it is meant to provide a short but intense meditative experience. “Meditative” implies suspension of linear time and spatial direction; circularity and simultaneity are basic characteristics of mandalas, the most effective tools for turning perception inward. In this temporal mandala, blank color frequencies space out and optically feed into black and white images of one love-making gesture which is seen simultaneously from both sides of its space and both ends of its time. Color structure is linear-directional but implies a largely infinite cycle; light-energy and image frequencies induce rhythms related to the psychophysical experience of the creative act of cunnilingus. Conflict and tension are natural in a yin/yang universe but atomic structure, yab/yum and other dynamic equilibrium systems make more cosmic sense as conflict models than do the destructive orgasms the United States is presently having in Vietnam.

(More truthfully, I had no idea of what I was actually doing while making Piece Mandala. My wife and I had been separated and I began the film immediately following our reconciliation; since then, in our unending attempt to understand what the film might mean, we have come to understand that that search – and then, the film – has been of the deepest significance in the reconstruction of our marriage. Only recently in Providence, while travelling with the poet David Franks, after awaking from nightmares and writing the following note to Frances, did it become clear to me that the film is properly dedicated to her: “seeing, at last, your mind as it must be at times in unendurable anguish, a series of events leading to that sense of self as burden, Artaud making art of it, misery, saw your minding of such in my own horror, shocked, shaking my head to get a feeling for what is dream and what is not, my head a crazy catalogue of images, classical symbols, cartoons of grief – but it is not always so and it is that lack of it which has to stand in for joy in the absence of blessings – and there are, in rare instances, blessings and you are often there at those places and I have a total sense of sense and you are absolutely cream, having to step on plastic flowers, my mind bursting, blossoming – someday I will tell you my dreams when it is quiet and I am more willing to let the tragic have its due warmth – that comes later; now I am content that my dreams were dreams”).

RAZOR BLADES/FROM AN APPLICATION FOR A GRANT: The film is made to be projected from two reels, the images appearing side by side; speakers are to be placed to create a stereo sound environment. Razor Blades begins as a mandala; the mandala is visually sliced open (as if one had passed through the center of the mandala, “through a looking glass” into a realm of pure imagination – consciousness dissected (and as the film’s “theme” gradually expands it becomes less and less rational. After the midway point in the film, the themes-images become more coherent again, begin to “re-center”; at the end of the film the mandala is reformed and the overall sense of the film is that a large cycle has occurred. Since Razor Blades ends as it began, an infinite loop is suggested – metric time is destroyed. Apart from the beginning and ending footage, which is linear, the film is made up of 14 loops which, staggered, play against (“slice” back and forth, interpenetrate) each other. Each loop, in itself, is made so that one can chart variations in one’s own consciousness of speed, rhythm and image recognition; when these loops are projected side by side, so that both images are seen as one large image, because of their differences in cycle length, this variability of consciousness is geometrically increased; since there are constantly different pairs of images on the screen, the repetitive characteristic of loops is transcended. Since Ray Gun Virus I have attempted to subtract from my imagery all potentially discursive – symbolic – dramatic-narrative meaning so that each film might create its own particular filmic “meaning”, so that each film will be a living system in itself. These “meanings” may be partially associative since recognizable images appear; still, these images are intended to be primarily plastic, even physiological. A “theme” which preoccupies my everyday being and that which recurs in most of my film work is that of the cosmic, dynamic unity of opposites, the orders of disorder, the sense of constant circularity … paradox as fundamental fact. In this work there is not only a formal sense of cycle but there is also a sense of the Life Cycle: mundane activity slashed open, revealing the positive-negative dynamics of sexuality, birth, growth, clashes at levels of reality, horror, confusion, absurdity, suicide; then, the “other side” of death-filled visions of life – the razor used to slash a wrist becomes Medicine (the life-giving scalpel) … ends becoming beginnings.

N:O:T:H:I:N:G/FROM AN APPLICATION FOR A GRANT: The film will strip away anything (all present definitions of “something”) standing in the way of the film being its own reality, anything which would prevent the viewer from entering totally new levels of awareness. The theme of the work, if it can be called a theme, is to deal with the non-understandable, the impossible, in a tightly and precisely structured way. The film will not “mean” something – it will “mean,” in a very concrete way, nothing.

The film focuses and concentrates on two images and their highly linear but illogical and/or inverted development. The major image is that of a lightbulb which first retracts its light rays; upon retracting its light, the bulb becomes black and, impossibly, lights up the space around it. The bulb emits one burst of black light and begins melting; at the end of the film the bulb is a black puddle at the bottom of the screen. The other image (note that the film is composed, on all levels, of dualities) is that of a chair, seen against a graph-like background, falling backwards onto the floor (actually, it falls against and affirms the edge of the picture frame); this image sequence occurs in the center, “thig le” section of N:O:T:H:I:N:G. The mass of the film is highly vibratory color-energy rhythms; the color development is partially based on the Tibetan Mandala of the Five Dhyani Buddhas which is used in meditation to reach the highest level of inner consciousness – infinite, transcendental wisdom (symbolized by Vairocana being embraced by the Divine Mother of Infinite Blue Space). This formal-psychological composition moves progressively into more intense vibration (through the symbolic colors white, yellow, red and green) until the center of the mandala is reached (the center being the “thig le” or void point, containing all forms, both beginning and end of consciousness). The second half of the film is, in a sense, the inverse of the first; that is, after one has passed through the center of the void, he may return to a normative state retaining the richness of the revelatory “thig le” experience. The virtual shapes I have been working with (created by rapid alterations and patterns of blank color frames) are quite relevant in this work as is indicated by this passage from the Svetasvatara Upanishad: “As you practice meditation, you may see in vision forms resembling snow, crystals, smoke, fire, lightning, fireflies, the sun, the moon. These are signs that you are on your way to the revelation of Brahman.”

I am not at all interested in the mystical symbolism of Buddhism, only in its strong, intuitively developed imagistic power. In a sense, I am more interested in the mantra because unlike the mandala and yantra forms which are full of such symbols, the mantra is often nearly pure nonsense – yet it has intense potency psychologically, aesthetically and physiologically. The mantra used upon reaching the “thig le” of the Mandala of the Five Dhyani Buddhas is the simple “Om” – a steady vibrational hum. I’ve tried to compose the center of N:O:T:H:I:N:G, on one level, to visualize this auditory effect.

From a letter to Stan Brakhage, late spring 1968: “The film is about (it is) gradation-progression on many different levels; for years I had been thinking that if a fade is directional in that it is a hierarchical progression, and that that exists in and implies forward moving ‘time’, then why couldn’t one construct inverse time patterns, why couldn’t one structure a felt awareness of really going thru negative time? During the final shooting sessions these past few months I’ve had Vermeer’s ‘Lady Standing at the Virginals’ hanging above my animation stand and have had the most peculiar experience with that work in relation to N:O:T:H:I:N:G (the colons ‘meant’ to create somewhat the sense of the real yet paradoxical concreteness of ‘nothing’ … as Wittgenstein so beautifully reveals). As I began to recognize the complex interweaving of all levels of ‘gradation’ (conceptually, sensually, rhythmically, proportionately … even the metaphoric level of subject making music, etc.) in the Vermeer I began to see what I was doing in the film in a more conscious way. I allowed the feelings I was getting from this silent dialogue between process of seeing and process of structuring to further clarify the footage I was shooting. I can’t get over the intense mental-emotional journeys I got into with this work and hope that the film is powerful enough to allow others to travel along those networks.

Light comes thru the window on the left and not only illuminates the ‘Lady at the Virginals’ but illuminates the subjects in the two paintings (which are staggered in a forward-reverse simultaneous progression creating a sense of forward and backward time) hanging on the wall and the one painting the inside lid of the virginal! The whole composition is circular, folds in on itself but implies that part of that circle exists out in front of the surface. What really moved me was the realisation that the light falling across the woman’s face compounded the light-gradation-time theme by forcing one back on the awareness of (the paradox of) awareness. I.e., one eye, itself dark, is half covered with light while the other eye is in shadow; both eyes are gazing directly at the viewer as if the woman is projecting music at the viewer thru her gaze (as if reversing the ‘normal’ role of ‘perception’) … I mean, the whole point is that the instrument by which light-perception is made possible is itself in the dark.”)

(POSTSCRIPT: Interrelated proportions welded into a formula consisting “of terms, some known and some unknown, some of which were equal to the rest; or rather all of which taken together are equal to nothing; for this is often the best form to consider.” –Descartes)

Obituary (1993)

Paul Sharits, 50, Avant-Guardist Whose Films Explored the Senses by Roberta Smith (New York Times, July 15, 1993)

Paul Sharits, an experimental film maker widely known in his field as a master of abstract film and film-projector installation, was found dead last Thursday in his home in Buffalo. He was 50. He died of natural causes, said his son, Christopher Sharits of San Francisco.

He was born in Denver on Feb. 8, 1943, and began experimenting with film while a teen-ager. He received an undergraduate degree in painting at the University of Denver and a graduate degree in visual design at the University of Indiana, founding experimental film groups at both universities.

In the early 1970’s, he developed an undergraduate film program at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio. From 1973 to 1992, he was the director of undergraduate studies at the Center for Media Study at the State University College at Buffalo. Of Sensory Perception

Mr. Sharits’s work was regularly included in film and video festivals around the world, and he exhibited his work in art galleries and international art exhibitions, especially during the 1970’s. Most of his efforts pushed at the limits of sensory perception. His installations of continuously running film clips, which often involved multiple projectors, could inundate the viewer in rich, rapidly shifting hues, flickering images and pulsating light, creating effects that were variously called hallucinogenic, aggressive and elegant.

Made with the use of elaborate drawings that plotted the color of each frame, these films sometimes resembled a kind of moving abstract painting. But Mr. Sharits insisted that his work was not abstract and that it simply exploited the physical realities of the movies: transparent film, projector and light beam.

A retrospective of Mr. Sharits’s films was held at the Anthology Film Archives in the East Village in 1978. His work is represented in many major museums, libraries and film centers in the United States and Europe.

Mr. Sharits’s marriage to Frances Niekerk ended in divorce.

In addition to his son, he is survived by his father and stepmother, Paul and Grace Sharits of Canon City, Colo., and two grandsons.

Postscript as Preface by Paul Sharits (January 1973)

The pieces printed here, due to their highly personal qualities and their lack of any clear aesthetic declaration (one being a letter of sorts and other a set of intimate journals), really demand somae introductory notes. The curious urge some artists feel to reveal the life and (cluttered) thought bases of their work is certainly not a valid mode of art criticism – “intentions” are not the proper concern of formalist analysis. However, one of the most pleasant characteristics of Film Culture has been its continual attentiveness to the personal statement. Perhaps this is because the American experimentalist filmmakers have a passion for “confession”; the beginnings of this cinema being “psychdramatic” further illuminates proclivity but does not explain it.

It may be that those who are drawn to cinema have some natural penchant, even though they might spend their careers trying to undercut it, for the diary, the chronicle, the dramatic – in short, for the “narrative.” In some senses, all of my films (with the exceptions of Word Movie, Inferential Current (which is a comedy despite its lack of plot or development) and Sound Strip/Film Strip, if they are not strictly narrative, they still do have temporal interior and exterior shapes akin to those of the narrative; but the films are so distilled, so conceptually-aestheically edited, that they do not always seem to come from the chaos of “life’s narrative.”

In my writing, I often forgo taste so that I might discover something more personally valuable: a reference frame for the spirit, from which hopefully richer surface structures may be generated. Certain incidents in a creative person’s life may not be an observable part of the concepts and/or forms that that person gives over to the world but those incidents may nevertheless be cardinal substructurally; those incidents may even be interesting, at least to those who care as much for the spirit as they do for its manifestations.

It is extremely interesting to me that Chomsky’s boat voyage to Europe in 1953 provided him the time and (desert-like but literally deep-structured) space for what must have been his agonized meditation on the ambiguities of structural linguistics; how marvelous it would be if we could “relive” those moments of confused reflection and inspiration which crystallized into formulations of the major premises of his post-structural theories – as it was, he had a struggle getting even the theories as such into publication!

The writings of mine which follow issue from a tumultuous two-year period in my life which I view as pivotally transitional. I look back on those years from an evolved pespetive and I am now able to both respect and be amused by them. The period was characterized by anxiety; personal and aesthetic transvaluations had to be performed but during nearly every moment of that time the most prominent and often violently exaggerated concern was with what was “real” and what was ethical. Tormented by the implications of film as a physical strip, I terminated my exclusive involvement with the film frame and the symmetry of my “mandala” series. This was coincidental with the collapse of my seven-year marriage, summer 1969. I had never been able to really separate the aesthetic and the ethical (Wittgenstein) and this new set of crises undercut my every confidence. I consciously violated my previous values, churned up the “subconscious”, experimented rashly in life style and filming modes; this was not pleasant. Finally, out of this sometimes comic but usually terrifying and often depressing state of being, I managed to finalize S: TREAM : S : S ECTION : S ECTION : S : S :S ECTIONED, December of 1970, the only work I wsa able to complete in two years. To me, this was a major aesthetic breakthrough; however, my life and spirit were still in their “season of hell”; another relationship collapsed and I frantically traveled back and forth from coast to coast, searching for something I now feel but still cannot express. I found what I was craving, several weeks after I completed typing up the fragments from my journals concerning S ; S ; S ; S ; S : S. Somehow, even while moving in and out of large east and west coast cities at a near self-destructive pace, I knew that the confrontation I needed to clarify my multitudinous confusions as to be found not in cities and peole and not in myself but in the vast quiet of the American southwest. (Therapy had been of some help to me but until I confronted the “ultimate deep structure”, the “existential terminus” which awaited me, it could not provide a belieavbel aid to self-regulation; after the experiences I will describe, Dr. Leonard Cobbs, had been suggested all along.)

In June of 1971 I set out on an elemental six week journey through the deserts of California, Arizona, Utah and New Mexico with my dear friend Hank Saxe, who had one of my most brilliant students. Even while Hank was able to explain every fault structur and rock or soil compound, this was more than a geologically edifying excursion: it was a most lyrical visionary experience. We visited volcano sites, grandly peculiar erosion vistas, a meteor crater, hundreds of miles of flat silence and spent several delightful days with a master Hopi jeweler and his family on the Shongopovi Reservation. We paid our silent homage to Georgia O’Keefe by assimilating what we could of the area around Ghost Ranch and Abiquiu. Each day I shot footage of earth and sky formations; a sense of relaxation was emerging. Then, several days deep in southern Utah’s “otherworldly” Escalante Canyon, backpacking with a small Sierra Club group, on the day of the summer solstice, lying on my back in a shallow part of the river, the water and the sun fusing, a distinct message was granted me; I seemed to be receiving revelations and instructions and they enabled me to feel at last a vital peacefulness and purpose. Months later, back teaching at Antioch, when I finally felt enough courage to process the 2,000 feet of thousand of images of cloud, rock, sand and dirt surfaces I had “taken” in the southwest (sometimes risking my life, climbing along steep, slippery boulders and what not), I was not devastated to find that the camera I had used had a light leak which pretty much negated all but perhaps 200 feet of imagery. In fact, this “negation” made the act of shooting (which had gotten me so much in relation with the earth and its atmosphere) an even more intensified spiritual engagement that it would have been if it had been “successful.” I now realize that the sky is a desert of sorts, and I have continued amassing 1 frame to 48 frame long pictures of its infinite configurations, regardless of what I am at on Earth’s surface. Or where I am located in blissful flight within my “subject.” To put the diary-like writings in further parentheses marks I submit a few of the specific theoretic findings which surfaced during this period which are still significant to my current analytical research, wherein I am making documentary films about the parameters of film stock. The following paragraphs are from a piece I wrote in fall 1979, “Words Per Page”; these paragraphs are not in the first publication of the essay, but conveniently together here, they can act as a forward to the more automatically written letters and journals.

Stan Brakhage’s massive work is too expansive in its implications and richness to discuss here except to mention that his use of the camera as a behavioural extension, his forceful modulation of distinctive, “distractive” “mistakes” (blurs, splices, flares, frame lines, flash frames, etc.) and his decomposition and reconstitution of “subjects” in editing, because of their cinematically self-referential qualities (they reveal the system by which they are made), bring cinema up to date with the other advanced arts. And, in another manner, Andy Warhol has demonstrated in his early work that prolongations of subject (redundant, “non-motion” pictures), because they deflect attention finally to the material process of recording-projecting (eg. To the succession of film frames, and, by way of consciousness of film grain, scratches and dirt particles, to the sense of the flow of the celluloid strip) are perhaps as revealing of the “nature of cinema” as is consistent interruption of ‘normative’ cinematic functions…

It is interesting to consider some phenomenological differences between painting, music and film: in viewing painting our experience is changing while the painting’s existence is enduring; in music both our experience and the existence of the music are changing; however, in film we have a case where we can experience both a changing and an enduring existence – we can look at the “same” film as an object, before or after projection (and it not a “score”; it is “the film”), and as temporal process, while it is being “projected” on the stable support of the screen. This equivocality of object/projection is further complicated when we admit that there are occasions when we are looking at a screen and we don’t know whether we are or are not seeing “a film”; we cannot distinguish “the movie” from “the projection”…

A listing of what constitutes filmic elements is confounded by the object/projection “dualism”; but at least a crude breakdown of the modes that the system can embody can be made; this seems necessary before “elements” can be located. There are at least: processes of intending to make a film; processes of recording light patterns on raw stock (films can be made which by-pass this mode); processes of processing; processes of editing; processes of printing; processes of projecting; processes of experiencing. The problem of whether or not “concepts” like “intention” are “elements” complicates the issue; that is to say, even those “things” which are observable, such as “emulsion grains”, can be shown to be essentially “concepts.” Remembering this difficulty, a partial list of elements which can be observed should be made as a (tentative) fundamental frame of reference. We can observe cameras, projectors and other pieces of equipment and their parts and their parts’ functions (shutters, numerous circular motions of parts, focus, etc.). We can observe the support itself, its emulsions before and after “exposure”, sprocket holes, frames, etc. We can observe the effects of light on film and, likewise, we can note the effects of light passing through the film and illuminating a reflective support. There is a remarkable structural parallel, which is suggestive of new systems of filmic organization, between a piece of film and the projections of light through it; both are simultaneously corpuscular (“frames”) and wave-like (“strip”)…

One thing we can say for sure about the release print of a film is that it is a long single “line” of film stock and during its projection, even though it may be structured according to retrograde vectorial concepts and even be experienced as temporally negative, it is, in fact, a straight line in our actual overall isotropic timefield. And the frames on the strip, as well as the image frame on the screen, regular and repeating. So, a homogeneously structured film would be as valid an amplification of the nature of film as would be a vectorial oriented work. In fact, from this angle it would seem that film experiences which had any variation would disrupt this sense of linear homogeneity and would in effect be anti-filmic. However, by considering one of cinema’s most basic syntagms, “the fade,” we discover a most natural way of reintroducing structural directionality, without negating either the continuous nature of the strip (the fade emphasizes the linear quality of the strip) or the flat, modular nature of the individual film frames (because the flat screen, being the most direct projection/image of the frame’s morphology, constantly refers our attention across its even surface in all directions to its edge, i.e., rather than looking through a “frame’ into a picture, we find ourselves looking “at” an image of the film frame).

My work of the past five years has been based on the importance of the fade; it provided a believable model for the vectorial construction of those works. My interest in creating temporal analogues of Tibetan mandalas, evoking their circularity and inverse symmetrical balance, led me to making what are basically two vector, symmetric works in which the first part’s forward directed structure is countered by the second part’s retrograde direction. A complex form of this vectorial approach, which issues a sense of isotropic homogeneity rather than a sense of developmental directiveness, can be obtained by overlapping or regularly intersecting two opposing vectors (i.e., superimpose a forward progression “over” a backwards progression); the whole work is, so to speak, a conceptual “lap dissolve” and will have the curious quality of constant but directionless motion. In 1968 I abandoned the mandala-like structures and am now working with a single vector form rather than dualistically balanced vectors; I have come to believe that while they provide discrete experiences, the latter are too closed and death-evoking in their over-stressing of “beginning” and “ending” and are, in this sense, models of closed systems.

Once the screen frame is regarded as a projection of a total film frame, we must begin to think about the appropriate scale relationships such as distance of camera from subject to distance of screen and projected subject, and viewer, and consequently, the size of the image to the size of its frame, and the size of the screen-as-image to the size of the wall on which it is projected. These features are normally regarded as arbitrary. Surface division of the projected frame has also been regarded as arbitrary; the flat film frame does not have the deep space most “shots” containing diagonals evoke, yet directors do not hesitate in using diagonal shapes in their compositions; rarely do these diagonals refer to the rectangular shape of the frame. If the film frame is a valid subject of footage, then footage should be considered a valid subject within the screen frame. A continuous scratch across frame lines down the length of film refers not only to the footage as a flowing strip but is also a valid internal division in its congruent relation to the verticality of the right and left edges of the frame image. An intensified splice not only refers to the horizontality of the top and bottom edge of the frame but it also interrupts the flow of our experiencing a film in such a way that we are reminded that we are watching the flowing of footage through a projector. When a film “loses its loop” it allows us to see a blurred strip of jerking frames; this is quite natural and quite compelling subject material. When this non-framed condition is intentionally induced, a procedure I am currently exploring, it could be thought of as “dis-framing”. I am developing another approach to simultaneously reveal both the frame and strip nature of film (both of which are normally hidden due to the intermittent shutter system), by removing the gripper arm and shutter mechanism from the projector…

Red, Blue, Godard by Paul Sharits (1966)

Godard’s first colour film was Une Femme Est Une Femme (A Woman is A Woman, 1961), two years later he dealt with colour for the second time in Le Mépris (Contempt). In both works the colours are dominantly primaries (“In Le Mépris I was influenced by modern art: straight colour,’pop’ art I tired to use only the five principal colours.”1)

Red and blue are the colours appearing most frequently in both A Woman is a Woman and Contempt; the recurrence of these hues in a variety of contexts suggests thematic implications. The films are also related in that their primary themes are love triads (a motif which later became geometrically equilateral in A Married Woman); in both, female nudity has the important function of finalizing a precarious relationship. Both are parodies, the former more obvious and comic while the latter is complex, oblique and tragic.

It is well known that working in colour often creates new problems for the intelligent director – an excellent description of these problems was given by Antonioni when he was interviewed by Godard.2 Godard, through his experience with A Woman is A Woman, seemed to learn that if colour was to function thematically, he would have to extend the length of single shots and slow down his camera movements to allow the viewer adequate time fo concentrating on the composition of colours.

Even a simple and incomplete inventory of the recurring colours in A Woman is A Woman indicates the importance of hue in relation to characterization and narrative development. Angela, the character who motivates the film’s action, is first seen in a red nightclub; her eyelids are shadowed blue. She is shown wearing a white coat and lives in a white apartment with her lover Emile. Camille and Paul, in Contempt, also live in a white apartment. In both cases, the white seems to underscore conditions of neutrality and/or situations whose final outcome is still ambivalent – Angela very much wants a child by Emile, but Emile, who is cool to the idea of Angela having a baby, wears predominantly blue clothing.

The neutral ground of the apartment contains a balance of red and blue objects: window awnings, clothespins, drinking cups in the bathroom, a sports poster on the wall in the living room, flashlights, a red lampshade and a blue bedspread. Seen through windows there are blue and red neon signs that consistently comment upon the emotional climate of each scene which occurs in the apartment. Angela is also characterized as indecisive at several points; one time she wears one red and one blue stocking, and another time she wears a red and blue plaid dress. There are red dots on her underpants. After being repeatedly refused by Emile, Angela goes to Emile’s friend Albert to conceive. Albert, the film’s straight man, wars grey and feels no real affection for Angela; he is, however, delighted to help her out. At this point Angela is wearing a blue dress and has switched to a black coat. When she returns to Emile, after having intercourse with Albert, she still wears blue and the dots on her underpants are also blue. When she informs Emile, however, the action is still ambivalent and Angela again wears the white coat. The film ends with Angela and Emile in bed, still under a blue blanket; both are sad and confused. Then Angela thinks of a way to solve the dilemma: red neon light pulsates into the apartment and Angela takes off her nightgown for a willing Emile.

Very rarely, since Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible, has colour in a commercial feature been used except to add market value. When it has been dealt with at all, it has been used primarily for the enhancement of mood in separate scenes. Godard has attempted a more ambitious function for hue in A Woman is A Woman: colour is used as a leitmotif which parallels and comments upon the narrative theme.

If a colour leitmotif is to be used, some system for structuring the colours must be created. In regard to the red and blue motif of A Woman is A Woman, Kabuki make-up authority Masaru Kobayashi’s comments are important: “…the basic colours employed in kumadori are red and blue. Red is warm and attractive, blue, the opposite, is the colour of villains…”3 These stylized, symbolic colour values are more than likely formalizations of direct sensual experience, formalizations based upon relationships of hue sensation and inner emotional states (what Wassily Kandinsky called “der inner Klang”). Eisenstein felt that these alleged correspondences of sensation and emotion could not be the basis for the systematic organization of colour due to the high degree of variation in subjective responses persons have to hues; instead, he suggested that each film creates its own “functional” system of organization, using arbitrary chosen but consistently recurring colours of values.

Godard’s colour system is in accord with Eisenstein’s theory insomuch as it is “functional” and its colours do not act upon the viewer in a direct sensual way. Godard admitted this himself when he made the following comment about a film in which each composition (through filtering and juxtaposition of hues) creates colour “auras” that establish emotional responses in its viewers: “I was very impressed with the new Antonioni, The Red Desert: the colour in it was completely different from what I have done: in Le Mépris the colour was before the camera but in his film, it was inside the camera.”4 On the other hand, Godard’s dominant thematic hues were very likely not chosen arbitrarily since they have such obvious symbolic references to emotional states.

Contempt follows the pattern developed in A Woman is A Woman but where in the former colour loosely parallels the narrative development, in the latter the leitmotif is more fully conceived, more complex, more visually apparent and becomes, in itself, a formative theme. Another difference in the film is that the blue and red system of the first is inverted in Contempt. While Angela sings of love in the nightclub of A Woman is A Woman, a revolving coloured spotlight casts first blue, then red light on her face. Immediately after the credits in Contempt, Godard again used a filtered effect: Camille and Paul and lying in bed talking about their love for each other, the shot is a deep red monochrome which abruptly shifts to “normal” polychrome; even in polychrome the scene remains warm in tonality (dominant oranges and yellows), but as the camera makes a slow overhead dolly her tone becomes cooler; then the shot shifts to monochrome again, this time to deep blue. In both films these filtered shots establish colour “keys;”in Contempt this prepares us for the overall movement of mood from warmth (red) to ambivalence (white, pink) to coldness (of course, blue) or, literally, from love to contempt.

Paul, a French detective story writer , has been asked by the repulsive, extroverted American film producer Jerome Prokosch (Jerry) to come to Rome to rewrite the script for his production of The Odyssey. Jerry I not pleased with the way in which his director, (the real) Fritz Lang, is insisting on the filming the book (i.e., the way it was written). Jerry wants to modernize the epic by inserting into it factors of causality (the very thing Godard consistently suppresses in his work). Even by accepting the assignment, Paul makes the first step in a series of steps which leads to his total self-demoralization. In these first scenes, Jerry wears a blue coat and a red tie; he drives a red sports car. Jerry is composed of both blue (dominant) and red so we may infer that the attraction he will toward Paul’s wife Camille, will be lust rather than love. Paul wears much the same colours (dominant grey and bits of blue) throughout the film and this is evocative of his passiveness and apparent lack of emotion. Camille, the most complex character, first appears in navy blue and white and wears a blue band over her blond hair; she wears the same colour in her last appearance, and, since she is in a constant process of changing mental states and garment colours throughout the film, this implies a cyclic development. Godard, in his treatment of Camille’s garment hues, seems to have broken with what he may have felt was a too-obvious colour system. Camille, because she is in love with her husband at the beginning of the film, “should” be wearing red; however, the cyclic motif that occurs in regard to Camille’s development has a particular irony paralleling Contempt’s development with that of the Homeric Odyssey. Francesca, Jerry’s secretary and lover, while a minor character, supports the colour key as a whole. Normally she is seen wearing a yellow sweater and grey skirt, but, during a scene in which she arouses Paul’s desire, she changes to a red sweater.

Camille and Paul are invited by Jerry to accompany him to Capri where Lang is doing the shooting for the film. Camille is dressed in pink (faded red) and grey (the first note of passiveness). Paul wears white and blue and Jerry has on a grey suit with a red and black tie. They are on the deck of Jerry’s boat, from which the Cyclops episode of The Odyssey is being shot; Paul is sitting in a blue chair. Jerry asks Camille to return to his temple-turned-home with him but she leaves the decision up to Paul; he consents, failing her again, Camille and Jerry leave in a speedboat which disappears from sight in a symmetrical shot, the top of which is blue sky and the bottom, blue sea. It is as if the boat had been swallowed by the water; Neptune’s kingdom now becomes the image of Camille and Paul’s fate.

When Paul returns to the temple with Lang, he sees Camille kissing Jerry and seems to partially realize the seriousness of the situation. He tells Jerry he is quitting but even now he won’t state the actual reason and says that he simply does not care for scriptwriting. He then looks for Camille and finds her sunbathing nude on the temple roof. She is lying on a yellow robe and next to her is a discarded red robe – discarded for good. She is now numb and when she says to Paul that she is barren of all feeling (she wears nothing) she is no longer acting. She puts on the yellow robe (perhaps a regaining of feeling, indicative of the beginning of a new cycle – one which excludes Paul) and they walk down, descend, to a ledge overlooking the sea. The composition of this series of shots is brilliant; as they get closer to the water, the relatively warm composition changes as progressively larger areas of the screen are filled with the blueness of the sea. Camille says, “I’ll never forgive you,” removes her robe and dives into the sea. While she swims, Paul falls asleep (Godard may have exaggerated Paul’s passiveness here!); we are watching Paul sleep while we hear Camille’s voice reading the letter she has written telling that she has left for Rome.

The scene is abruptly changed to Jerry, wearing a red sweater driving Camille to Rome in his car. Camille wears the same colours as she did at the beginning of the film, implying the completion of a metamorphic cycle. Like Odysseus, she and Paul have been on a voyage, a voyage ending with the submersion of their relationship. Camille, at least, has regained her original stability – somewhat in the was that Odysseus has regained his homeland (Odysseus, in Lang’s picture, wears blue when he returns to Ithaca). Jerry stops for gas and while waiting he picks a small red flower. He pulls out of the gas station in a characteristically reckless way and just before they collide into the side of a petroleum truck, we see the final words of Camille’s letter while hearing the crashing sound of the collision. Then there is a cut back to the wreck – a slow dolly toward Camille and Jerry’s dead bodies; cut again to Paul, suitcase in hand, walking up the staircase of the temple at the film site where Lang is shooting the return of Odysseus. He passes Francesa (wearing blue) who is walking down the stairs; he pauses but she ignores him; Paul continues up to the roof.

This study by no means exhausts the wealth of colour imagery in Godard’s two works. Due to the relative inaccessibility of the films, there are necessarily many gaps in this analysis and interpretation. It is a certainty, however, that Godard has shown a new way of effectively using colour, at least in commercial filmmaking. (Stan Brakhage’s Anticipation of the Night, made several years before A Woman is A Woman, has as complex and systematic use of colour as Godard’s films.) Within the realm of the commercial film, Godard has accomplished the unique task of casting colours effectively in major dramatic roles.

Notes

1. Godard in the New York Film Bulletin, no. 46, 1964, p. 13.

2. See the English edition of Cahiers du Cinema, no. 1, 1966, pp. 28-29.

3. Sergej Eisenstein, Jay Leyda, The Film Sense, Faber and Faber, London, p. 137.

4. New York Film Bulletin, p. 13.

Correspondence with Stan Brakhage

May 20, 1966

Dear Mr. Brakhage,

In my article – RED, BLUE, GODARD (an analytical study of A WOMAN IS A WOMAN and CONTEMPT) – whish is to be published in the Summer Film Quarterly, I say in conclusion: This study by no means exhausts the wealth of colour imagery in Godard’s two works. Due to the relative inaccessibility of the films, there are necessarily many gaps in this analysis and interpretation. It is a certainty, however, that Godard has shown a new way of effectively using colour, at least in commercial filmmaking. (Stan Brakhage’s Anticipation of the Night, made several years before A Woman is A Woman, has as complex and systematic use of colour as Godard’s films.) Within the realm of the commercial film, Godard has accomplished the unique task of casting colours effectively in major dramatic roles.”

I’ve only been able to see ANTICIPATION a few times but I feel sure that I am correct in what I say about it in the Film Q article. Your notes in METAPHORS seem to reinforce my intuitions. However, I have never been able to verbally interpret the functions of colour in your film and it has recently occurred to me that I cannot intellectually defend my position. As I’m sure you are aware, I’m not after an easy way of understanding (via some literal-symbolic “key”) your film. What I am asking for is an indication of the perspectives thru which I might more successfully respond to your colour. Even your briefest clarification on this issue will be heartily welcomed.

I was able to see your PRELUDE several years ago when you brought it down to a Denver University film group showing. Recently I was able to see it and all the following sections of DOG STAR MAN (at once of the meetings of the Indiana University EXPERIMENTAL CINEMA CLUB which I sponsor-direct – our initial, Spring ’66 program was made up entirely of New American Cinema). Am I wrong in my feeling that PRELUDE has been re-edited? I am sure that several shots and sequences have been removed (one involving cunnilingus) and that the order of the film in general has been rearranged.

I’ve always had intense responses to your work but, after having taken LSD several times between the first viewing of PRELUDE and this recent viewing, I feel my involvement in and understanding of the work has been very much increased. This experience was even more vivid for a close friend of mine: he laughed at DOG STAR MAN when he saw it a few years ago in NY but at this recent showing he nearly had as intense a psychedelic experience as he had had with LSD – he also attributes his more empathetic perception to the chemical experience. I view of these personal responses, we were both startled when we were informed that you seriously object to LSD.

I hope you will be able to see my recent film RAY GUN VIRUS when the EXPERIMENTAL FILM GROUP at CU shows it this August.

Thanking you in advance,

Yours very sincerely,

Paul Sharits

Late May, 1966

Dear Paul Sharits,

Yes, okay – to be brief, then…

It seems as silly, to me, to write a long (or short) dissertation on the aesthetics of Godard (or any of the other so-called “New Wave” film-makers, and/or the “big splash” Swedish film-makers, Bergman, etc. and/or almost all those who come onto us via “Art” with a cap. “A”) as it would to write on the aesthetics of Zane Grey (a “Pop Art” joke, at best) and/or John O’Hara, for that matter (which DOES happen seriously in the so-called “Serious” ((with a cap “S”)) “Lit.” ((with, etc.)) magazines) – shit… come OFF it. The fact that Godard/Trauffaut (Sic)/Renais?/et-al make escape movies for tired intellectuals rather than, as of most Hollywood, for sex-frustrated teen-agers DOESN’T elevate their efforts to the stature of an art: and all the statues-and-tutes in the world won’t, thank lucky real stars! Alter that fact… other than to sow the usual confusion among the confused as usual – what I take YOU to be doing in writing the article you’ve described. Until you learn that “The Cremation of Sam McGee” –type-movies AND the “I-think-that-I-shall-never-see-a-poem-lovely-as-a-tree”-type (French-serious/despairing)-movies are EQUALLY escapist/fiction (in the sense: “making up a story,” as Charles Olson nailed ALL fiction) and to distinguish them from film as art you won’t know a Joyce Kilmer from a James Joyce of the film medium. Throw away our perspectacles AND your,like everyone else-academic, sense of “successful” – all that which would make you worry about whether or not you can “intellectually defend” your position on ANTICIPATION OF THE NIGHT – and you’ll… th’ there is some point to seeking advice on aesthetics (and/or giving it, writing about it) when a approach to art as an historical form is in quest-shun, because aesthetics is a complex a subject as physics, for instance, and an historical perspective on a work of art as difficult as any more than superficial understanding of E = mc2: but do NOT, please, anticipate any more respect out of me for an article on the aesthetics of Godard than you would from any competent scientist for one on the science of teeth brushing… and don’t expect to get any further “perspectives thru which (you) might more successfully respond to (my colour” so long as you’re involved in treating high-brow entertainment and escapism as if it were anything more than just exactly THAT. What a lot of wishy-washy wasted effort is all this apologetic pedantism which purports to find significance and to point out in lurid detail the influence of, say, some great classic on, say, the latest best-seller: but you, and most other film critics, don’t even aspire to that or you’d be doing an essay – or what-did-you-call-it? – “analytical study” – on ANTICIPATION OF THE NIGHT as an influence on Godard or some-such… which wouldn’t interest me either.

As to PRELUDE: DOG STAR MAN – No, it hasn’t been re-edited (I don’t re-edit)… it is made to be seen a number of times(as all my work of the last, say, 10 years – except “Blue Moses”) and, as such should reveal a different complex of meanings at each new viewing (one of the primary distinctions between works of art and anything else in say, lit, paint, movies, etc. being the “lastingness” either in terms of remembrance or repeatability of the experience of the former as other than the latter.)

When you take LSD (and/or any other drug, etc.) you are in to your whole physiology – your psychological response to this being creased tho’ distorted, thru biological desperation, percept-ability (the other side of the coin of academic spectacles)… what’s the matter? … aren’t there enough imposed crises’ upon you to keep you kicking/high-stepping, etc.? … or are you in fact shunning these more natural crises’/life-given responsibilities (if you’ve ability to respond) in a fake/controlled/mechanistic drug take? – I don’t know (I’ve never felt the need of it – regard my chaw of tobacco as betrayal of my sensibilities which I must beat my habit-bound way out of… I mean, I want to have “my life to live” in some way Godard can’t even, apparently, dream of) …okay, you tell me –sometime when you’re clear about it. (But get clear about this right now: I’m not forming some anti-LSD league, don’t “seriously object” to it in the sense you implied in your letter: I just don’t feel any need of it and wish my friends, actual & potential, didn’t either in the same sense I wish they wouldn’t commit suicide, sell-out to Hollywood or Mad Ave, etc. … i.e. – I want to live in the same world with them.)

Blessings

Stan Brakhage

June 3, 1966

Dear Mr. Brakhage

Thank you for yr (venomous) “blessings” & for the “perspective” they unfortunately reveal in regard to your work. I kept saying to myself “he’s putting me on… this is jus his game… he can’t be serious…”

But, I guess you are… serious.

I’ve destroyed a lengthy reply because it was vile & could only lead to further misunderstanding, etc. My letter was misunderstood but whether this was my fault or yrs matters little. Please let me clear up my “position” – it’s really impossible to begin – things, are, seem to be more complex than you suggest. First, a few misunderstandings… then, out-rite disagreements:

I am not (for g’s sake) a “film critic” – I am merely a bundle of cells who SEES worth in more than one of life’s dimensions – apparently in several dimensions which yr clear, open vision has chosen to disvalue.

I don’t care – nor did I write for – your “approval” “respect” “endorsement” etc. I believe I am aware of yr position in regard to European directors. By the way, have yu SEEN Mr. Griffiths INTOLERANCE?

My article has nothing to do with ART. I leave that subject to the actual pedantics. I am concerned with what I see, not what I have been trained to ignore. While yu struggle with yr tobacco addiction, I struggle with my preconceptions. (All shit is Art)

What amazed me most about your letter was its extreme academicism (sage to student, grave concern with the preservation of conventional/established Values, the Good, True & Beautiful)… in a word (a mouthful at that): ART ((my “per-spectacles”?? my closedness to potential incoming data?? my distortion of nervous system?? – the nervous system, I am told, is an open system until it is willingly/gamefully deformed by elementalistic, “know it all,” either-or, static, absolutist, imprinting/conceptualizations such as concepts – rather than the “formulations” – of “real,” “natural,” “fiction” etc…)) and so forth…

ON “FICTION” is making up a beard & long hair & then removing said props from head…? Are yu wound on a film reel titled DOG STAR MAN? Angry answer anticipated: “no, I am obviously not my films, they are constructed in such ways that they are themselves thus, not fiction. Next question: is this not true of any of man’s products? Zane Grey et al? A matter of degree?

FURTHER I certainly hope that Mr. Markopoulos (one yu seem to have shared much with) doesn’t fall into THE GREAT FICTION BEAST category. If so, shall he be slain? Or is he somehow an exception to Mr. Olsen’s TEN EASY RULES & YU CAN GAIN A ‘POUND’ OF ART PER DAY?

ON ‘TIRED INTELLECTUALS’ Of course I have nothing to defend or protect but I hope yu have not put Mr. Olson in this category since he despairs certain changes in New England; I hope Jonas Mekas is not in this category because he is able to SEE Dreyer, Godard, etc.; I hope yu don’t place yrslf in this category due to yr concern/despair over “Pop Art” (whatever that “is)) degenerate escapsism, duped masses, etc.

ON SIN IN THE ACADEMIC SUBURBS, DOPE FIEND, POISONED SOULS… I am finding it very difficult to type, being as I am, in this abnormal DRUG STRUCK STUPOR. If I can ever kick this monkey & get back to Real non-mechanistic responsible down-to-earth lusty well adjusted noble savage rugged individualistic Thoreau-like conditions, perhaps my thoughts will clear up a bit. I’m not going to argue to try to convince anyone about the virtues of pot-lsd… T. Leary (particularly in ETC, Dec ’65) is much better with that sort of thing. That yu can actually believe that culturallylearned defense mechanisms are the Totality and peak of “what is Natural for man”… well, incredible! Now, if I were to say (& I am going say) that yr films tend to imply, even induce psychedelic states, wld this bother yu? Just imagine: DOG STAR MAN the stimuli for an entire audience “flipping out” of their old response patterns! Immoral?

Yes, IMMORAL!

Perhaps one of these days yu will SEE for yrslf & maybe your per-spectacles will be transformed to in-sits. For being anti “Pop art” yu certaintly concur with the READERS DIGEST on this issue.

Well, fuck… I have still ended up writing a vile letter & I have no right to do so. I wouldn’t say anything like this to someone who didn’t count with me. I’ll have to send this quick before I get rational & reconsider what I’ve said… It just bothers me that I’ve been reproached by the “other side” for being enthusiastic about yr work for the exact converse reasons that yu… etc… (actually it doesn’t bother me at all; I enjoy playing the Total Dupe Game – definite lack of good old-fashioned Integrity).

In ending – your work has always & will no doubt continue to “turn me on” (whether yu like it or not). I hope you won’t mind that I shared yr letter with Henry Holmes Smith (photography prof & pioneer ((neglected pioneer)) of dye transfer printing & photograms). He was more empathetic to your letter than myself (an up-start kid) – he was quite touched by what yu said & asked that I pass on to yu that he felt privileged to have seen DOG STAR MAN (a sentiment I share) & that he will book a sequence of your works in the Fall program of our club (I won’t be around in the Fall so he will be doing the programming).

Earnestly,

Paul

P.S. Enjoyed yr piece in YALE MAG, even though it reeked with intelligence. I think, however, yu have underestimated Burroughs. I was disappointed, by way of that journal, to learn that Sitney has adopted the “party line” – I wonder how long it will take for Mekas to weaken.

Early June, 1966

Dear Paul Sharits,

Hey-look… I apologize… I mean: I didn’t intend my blessings to be “(venomous)” – wow! I was sick last week, and broke, AND bugged by just about everything: and I guess you got some too much brunt of it in that letter. I don’t think I wrote you anything I don’t believe to be true; but it was only “a piece of my mind,” like they say… certainly not even a balance of pieces, if I can judge by your reply. I do remember stressing apropos LSD, etc. that I wasn’t writing “moralistically:, but then, perhaps, I was being moralistic – between-the-lines – again, to judge from your reply – and I’m sorry, if so… okay?

Anyway, as to “story”- I think every film of mine has one, some story-level operating thru the interstices of whatever complexity… only in most of the works, and certainly in all the latter ones, story arises out of the necessity of the art taking shape, NOT t’other way round (THAT process making “illustration” of painting, “program” music, etc.): and I think those latter works are more “true to life,” like they say (just because it is not some – “holding a mirror up to nature” – such which seems to me a trickiness, an artifice and, as such, certainly not an art) – those latter work seems to me more organically coming into being, having more a life each of its own, then: and that seems (again I stress, to me) a distinction I honour and, more importantly, a loveliness worth working for. I also find that ‘competition’ is an idea destructive to my creative processes: and so I seek to make distinctions so that I can honour each thing for its self’s being. I do not think that a great work of art is more important than a great escape movie – it certainly is not to a man at a moment when he needs an escape movie (a position I’m often in) – except, perhaps, that the former is more rare and hard to come by, thus often more needed. I admit to an annoyance (and sometimes a raging prejudice) against what seem to me to be escape movies – which-are-advertised-as-works –of-art; but I must also admit that I have no absolute way to determine the one from the other (except my own senses of need, which have often been frustrated by the commercial “Art” theatres), that I am assuredly wrong, to others, in many of the distinctions I’ve made and very likely wrong for myself, even in time (I mean I brood a lot about the fact that Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, and James Joyce all disliked and discredited each other; and I fret about who’all I’m not seeing because of proximity of vision, etc.) and am absolutely wrong to write disparagingly about your piece of writing (which I haven’t seen) about that particular Godard film (which I haven’t seen)… okay? But, out of my own anti-competitive necessities, I feel impelled to go on attempting distinctions (even at the risk of being called “academic” – aghhhrrrr, I guess that was a fair blast back from you after I’d hurled “critic” at you), because if it is all a “matter of degree,” as you suggest, then that would make Beethoven top-dog over Zane Grey, etc. which seems to be a dangerously nebulous proposition.

We’ve got a little money in the bank this week, and I’m well again, and I’ve begun labor (which was a long-pregnancy time coming) on “23rd Psalm Branch,” and I’m joyful to some realizing-myself extent that I don’t give one damn whatallever I’ve written about anything (including that whole book of mine which I can only hope will be helpful to others and won’t hang them up like it did me for awhile a couple of years ago)… and except to hope you’ll forgive me for being such, apparently, cranky letter writer last week – okay!

Joy to you, Stan

June 11, 1966

Dear Stan Brakhage,

Your letter was very welcome! Words are ass-holes aren’t they? Not always. As yu say, distinctions are operational. In my suggestion of a continuum of degrees I didn’t mean to suggest hierarchical valuing… that is what I’d like to get away from… again, as yu say “words/words”… well, it’s is all very confusing to me, and very exciting because of that, so…

Highest regards,

Paul

Mid-November, 1966

Dear Paul,

(…) but my enthusiasms after seeing your film “Ray Gun Virus” was such that I would have sent you a telegram if I could have afforded it! I think I do really have a very western union with you over that film in that we are working along the same West Ho!

Cultural line of development, viz: the un-masked flash!

I showed Gregg (Sharits, Paul’s brother) the 1st ten min. of my work-in-progress called “Scenes From Under Childhood” and he/we – all were amazed at certain specific similarities: and then also the “23rd Psalm Branch” of mine is integrally involved with the physiological rhythms of memory re-call (as the optic nerve flashes in the act of memory). Anyhow, I really do think you have a very fine film there of magnificent subtlety in its by-play with the texture of film and eye’s grain, etcetera; and I do very much want to spend a great deal of time talking with you about seeing it again and again (…) We also, apparently (from current Film Culture) share something with Tony Conrad (I don’t know what, as I haven’t yet seen “Flicker”) – and, of course, Peter Kubelka (his portrait of “Arnulf Rainer”). What would really be a focused occasion would be a seminar involving us four (and Kubelka will be back in the country by that time – he has a job now at the U.N.): but I suppose you’ve already made your plans with regard to USCO, etc.

Anyway – looking forward…

Joy to you,

Stan

Undated (probably late November/early December 1966)

Paul Sharits/Fine Arts/St. Cloud State College/St. Cloud, Minnesota

Dear Stan,

I am really overwhelmed by your letter – ie. having someone whose vision I greatly respect respond favourably to my work… thank you! it’s pretty hard for me to say anything terribly specific or coherent about ray gun virus because it is, in a sense, the integration of a number of feelings-ideas developed over about a five year period of working mainly in sculpture and painting (which I’ve given up for film in last few years)… as a student.

I’d like to explain some of my thoughts-ideas-feelings “on” film to you – not very radical, probably confused-sounding, started in rather narrative-dramatic way (an interest in haiku, metaphor, etc.); got more & more interested in visual structure; have always & still do resist idea of “abstract cinema” for several reasons: because my work in painting/sculpture was never figurative (it was “abstract”/”non/objective”) but I wanted to preserve my independent-of-school work in film from falling into those (…) terms; I am wary of categorization (“abstract cinema”) and the idea that one can “understand” something by labeling it (labeling has, for me, always led to “putting aside,” “feeling comfortable with,” etc) I keep trying to cancel out of my work any specific meaning. Seeing anticipation of the night was a very strong directive experience for me (I was upset though with your notes on the film for Brussels… I didn’t want to ever know what the film was “about”) to a degree, chemical “psychedelic” (crappy word anymore) experiences have influenced my work of last several years, the experience allows for an intensification of the senses (perhaps simply by blocking higher cortex evaluation patterns such as “visual constancy” and so forth), gives on the feeling that he is perceiving perception itself and throws one into intense, direct, immediate, non-verbalizable consciousness of “reality.” Gave me the chance to see that single colors are not single at all – I saw several colors at once, where, in normative experience, I would see only one rather flat material-like (rather than light-like) solid hue. “color flicker” intrigues me because it has certain parallels to the feeling that you are looking at pure light color (which we are always doing but do not recognize as such). As you know, rapid successions of 1/40-of-a-second flashes or images creates merging of after-images. I like that idea of not being able to see what is “out there” but seeing your own processes of perception (something like “art as a mirror”). I am concerned with the kind of assaultiveness joseph albers was talking about when he said something about “art looking at you.” I want the film I do to be somewhat resistive; someone told me that they were apprehensive, uncomfortably so, when watching ray gun virus (it’s just a movie, light flashes on a flat screen – why am I here with this strange assembly of individuals, in the dark, eyes trained on a spot of light as if something is going to happen”). This is great; that’s the way I feel myself about the thing… I become aware of the ritual when I become aware of how mundane the film is, the sense of hyper-mundane-ness is similar to that stage in the “psychedelic experience” when one sees that it is not fantasy that is magic that that it is the harshly mundane that is awesome full of magical beauty. Like kandinsky (or perhaps because of kandinsky) I am interested in optical sensation only inasmuch as it leads to striking inner spiritual chords – “der inner klange.” O the other hand, I am very sympathetic to art which is not very physiological at all, for instance, the works of tobert morris, frank stella, donald judd, etc. as contradictory as it may be, I am response to opposite ends of the “art continuum” – from redon & his closed-eye worlds and Gauguin, the music of color, mondrian, duchamp…to Warhol. I even like very much theatrical-narrative-illusionistic cinema (godard, resnais, et all) most everybody tells me I am tasteless for one reason or another.

Warm regards,

paul

Undated (early march?), 1967

SAINT CLOUD STATE COLLEGE

SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

DEPARTMENT OF ART

SAINT CLOUD, MINNESOTA

Dear stan,

During your visit you made some remarkable statements about visual perception… an area you seem to have empirical understanding of than any psychologist I know of – I particular I am thinking of the data on methods by which one may see I negative, black and white, up-side down… grain & inner light, etc. later we both agreed that yoga was strangely devoid of visual training methodology, probably due to its ultimate non-sensual goals; this seems to a specific case of a general neglect of an enormously important area of human experience… & the notion of physiological art…neglect in art literature of processes artists have – do use to regain or attain non-conceptual responses to the world. A few random reflections: surrealists meditating on white surfaces for long periods of time in order hallucinate… yogic use of mandalas and yantras… my brother’s interesting concept of eye blinking as biologic splice (if I can ever find what he wrong on it, I will send you a Xerox)… my favorite pastime of paying equal attention to 5-7 or 8 separate things going on in the visual field all at once & without allowing myself to gestalt these into one rhythmic totality… general semantic methods of visually concentrating on a common known object until one loses his word for the thing (kozibski has good statement on value of “silent levels of abstraction” on page xlix of MANHOOD OF HUMNITY)… a book called GESTALT THERAPY is also of interest… an article on light effecting the pineal gland (and consequent changes in visual perception – in schizoids & lsd experience) is found in a fall issue of atlantic monthly, called “lsd & the third eye”…. Dr. oster’s article in an issue of the psychedelic review on grid structure of eye which seems to account for optical moiré effects… extremely interesting chapter on brain waves & epilepsy (and relation between pre-seizure an& schizoid perception & “genius”) in book THE MACHINERY OF THE BRAIN by woolridge… sound psychology’s findings on cultural differences in perception… etc…. oh yes, sensory deprivation findings in book called THE BLACK BOX….

Mcluhan of course plays down visualization but perhaps he isn’t aware that we are rapidly entering THE LIT EAGE & that light is basically received through the eye. Technology finally develops to the point where our culture is a material manifestation of the most fundamental metaphor of all religions (enlightenment, clear light, burning heart, halo, the Word Is the Light, et al). I am just remembering what maria gruver was telling us about blind children – that their world isn’t dark but populated by inner light/and orgone light (someone ought to see if it is possible to project, perhaps by laser, light from orgone box… orgone beam, orgone strobe, etc). anyway, what I am getting at is: (1) that we are both very concerned with virtual, time-color, equivocal shape thru color frequency (open eye phosphenes)… PHYSIOLOGICAL MAGIC… and… THE MORALITY OF USING SUCH MAGIC (shall it be white or black magic?); (2) you should write some essays or something on these things. I would be willing to work somewhat as an understudy of something & help collect data if you would be willing to program all this into something coherent. Perhaps you are already involved with something like that. Perhaps there would be other artists who would supply their knowledge – I am thinking in particular of jud yalkut and tony contrad who probably could make some important contributions… and of course, kubelka, this could be a hell of a lot more significant than most “aesthetic criticism” that is going on. Just an idea, randomly stated; maybe it will capture your interest.

April 18, 1968

Dear Stan,