The Invisible Man 18 minutes, video, 2003

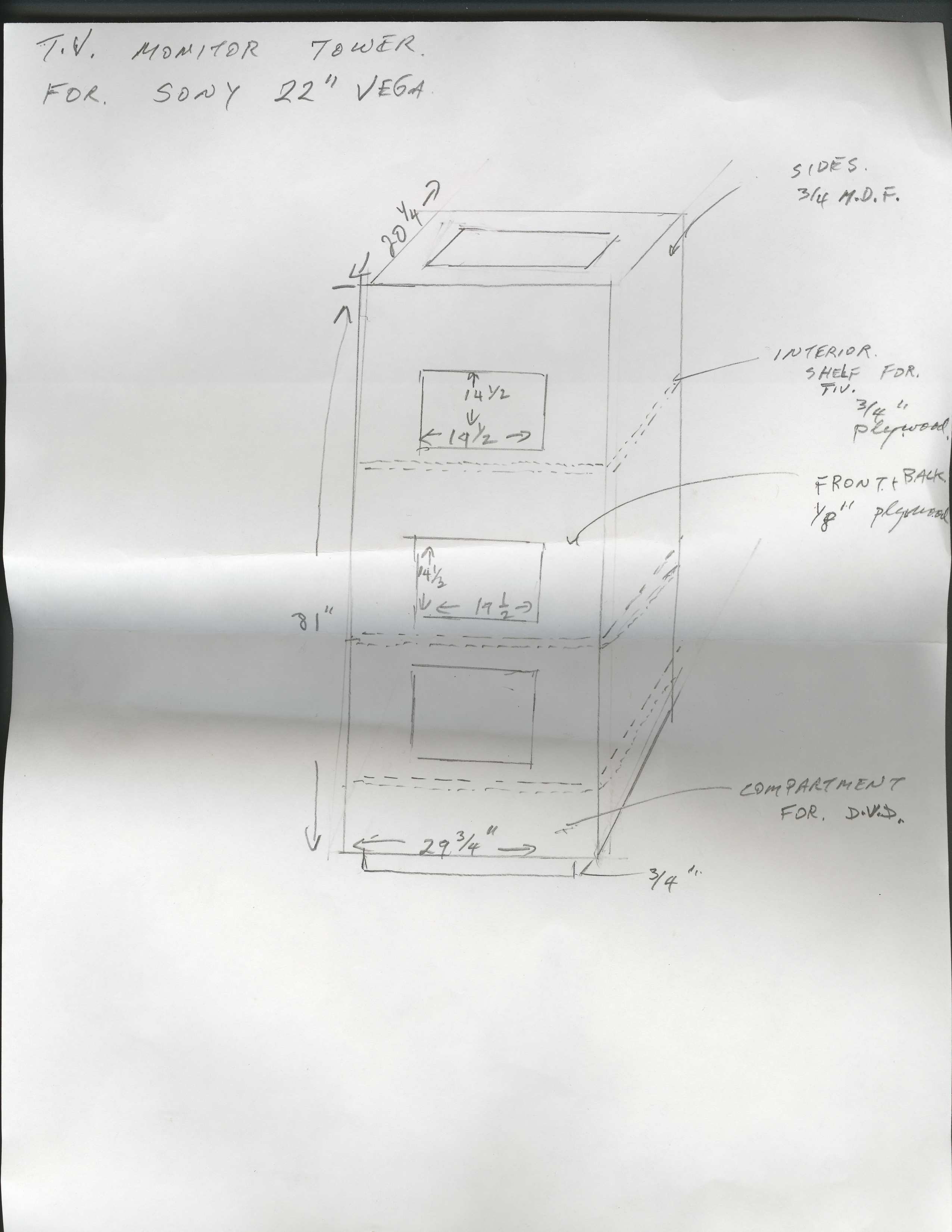

The Invisible Man is a motion picture installation which shows two (sets of) images facing one another. There is an eighteen minute projection entitled The Invisible Man, and on the other side of the room a case holding three monitors, stacked one on top of another, each showing a different loop. These identical monitors sit on shelves inside a free-standing, dark-painted wooden box, which contains three dvd players at its base. The top monitor is roughly eye level. Three ‘windows’ cut out of the box allow viewers to see the three monitor screens. Sound comes from the projection and requires two speakers placed on either side of the screen.

The top monitor was shot in Vila do Conde, Portugal, and shows an old man, a middle aged man, and a young boy, each inhabiting the same space, but at different speeds, and apparently independent of one another.

The bottom monitor was shot in Toronto, Canada and shows a man making repairs to a train track at night.

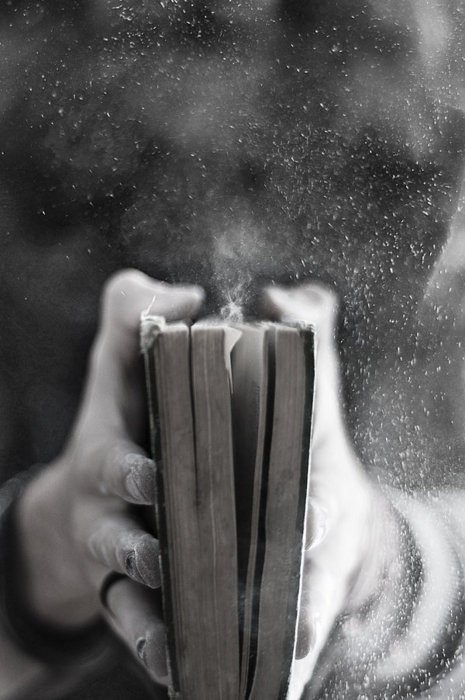

The middle monitor shows a dying man in a hospital bed. The oft-remarked flashback which accompanies the last moment of life is presented here as a series of layered and overlapping memories of childhood. This dying man has become his body, the water of his body, the water which bears his memories back to him. These reflections on beginning and ending are framed by the shots above and below.

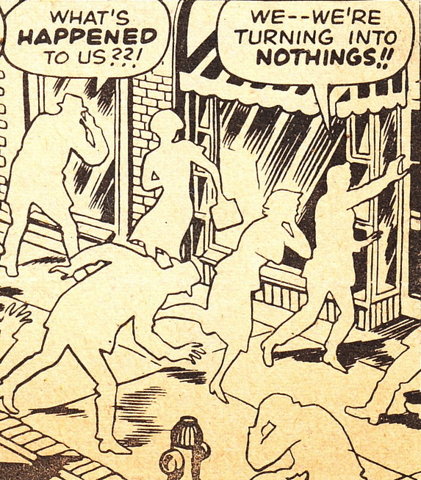

The projection which bears the title The Invisible Man shows the journey of a man in search of his roots. He is pursued by his childhood self who has already written his own future, and foretells the amnesia which will doom this traveling. It is a life made of pictures, an allegory and reflection of life inside ‘the society of the spectacle.’

Hoolboom hits gallery by Cameron Bailey

For years, Mike Hoolboom’s spectral film and video work has stood on the threshold of contemporary art. Now it’s tripped right into the gallery. The Invisible Man marks the first time the director of experimental classics like Frank’s Cock and White Museum has submitted to a solo exhibition inside the art world’s square box of significance. Curated by Philip Monk, who previously seduced Guy Maddin into the Power Plant, the show at York University reveals a powerful new context for Hoolboom’s work. Installed large-screen in one darkened room, Imitations of Life immerses transient viewers in reflections on moving images and the shadows they represent. In the chamber next door, three video monitors offer stray echoes of the unfolding picture mystery on the big screen. Hoolboom’s recent work opens up in the gallery, where meaning projects in all directions. (Art Gallery of York University, January 3 to 30) (NOW Magazine, Dec. 30-Jan. 5, 2005)

“Mike Hoolboom works in an essayistic mode, deriving his films from a montage of images drawn from Hollywood film, found footage, and home movies. Onto this confabulation of images, Hoolboom overlays a meditative narrative on living and dying, of living forwards and backwards, of remembering and forgetting, parlayed through the common picture world, the image world of movies.” (Scans, January 2005)

“Dreams and memories are starting points for Imitations of Life , a work by fringe filmmaker Mike Hoolboom in The Invisible Man at the Art Gallery of York University. In a montage drawn from home movies, TV commercials and Hollywood cinema, it’s a testament to the power of photography and the temptation to live vicariously through borrowed images.” (Canadian Art, Winter 2004)

Akimblog by Isa Tousignant

September 20, 2006.

Concordia’s Leonard and Bina Ellen Gallery launched the season with something a little different: an exhibition by Toronto experimental film luminary Mike Hoolboom. I love the recontextualization; boundaries are always fun to break and arties are such preternatural snobs. Since it was taken over by Michèle Thériault a couple years ago, the Ellen Gallery has presented a selection of exhibitions unwavering in both high quality and formal raison d’être. The tenets of modernism have reigned as well as a decidedly tasteful and serious aesthetic. Hoolboom flourishes within those confines, but brings a light, narrative quality that makes experiencing his work easy and entertaining. He creates through association, making films out of bits of other films culled from Hollywood, home movies and documentaries. The flow of each of the four big-screen pieces (united under the title The Invisible Man) boasts the natural and thematic logic of dreams, creating patterns and trains of thought we the viewers then reassemble for ourselves based on what information we retain. Welcome to art, Mike.

Birth to Cinema: Mike Hoolboom’s Invisible Man by Philip Monk

Last night I had a dream: that the movies I had seen even in the womb were a prophecy. They were my future.

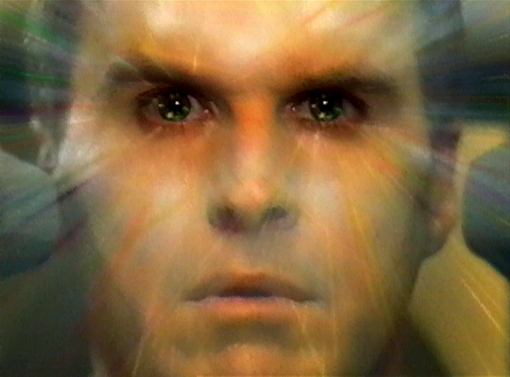

A child’s voice speaks these words, as if epigraph to Mike Hoolboom’s installation The Invisible Man. But where is this child, wise beyond years, speaking from, what place in space or time, or even the trajectory of his own life, to frame what we are about to see? Aside from all implications, we must remember that he is also speaking to us from film—that, for all we know, film is the place of his birth. As such, it is also the place of his demise, or the demise of the self in the prophecy film paradoxically programs for the individual: he is to become old by growing into the image of himself that cinema offers.

The image world of film is a world we already all share. Not merely entertainment, movies are patterns we grow into, but more than just as role models. As with the child already too old, they herald our future. At least this is a premise of Hoolboom’s installation, but it takes rearranging film to make this message obvious, to bring out its mythic structure.

Mike Hoolboom derives his films from a montage of images drawn from Hollywood film, found footage, and home movies. He pillages others’ products to produce streams of images stripped from their original narratives, but when the images are put back together according to another logic they now flow like a dream. (This dream logic is common to our reception of even the most realistic of Hollywood films and begins when the theatre lights descend.) In Hoolboom’s hands, film becomes an aqueous world shot through with light as if it was an embryonic fluid in which a form of consciousness comes to birth. Through his use of appropriated pictures, Hoolboom doesn’t produce an analysis of images, except perhaps as a poetics; he proposes a form of being. His is an ontology of cinema. But cinema also includes us, and this ontology becomes ours, so flows of images, flows of time, and flows of life are conflated in individual consciousnesses, the spectators that receive images and consume movies. This receptivity on our part to the film image lends credence to the phrase “a life in film” such that Hoolboom suggests, like the child, we too are born and die through the movies.

In the future each moment will be photographed, doubled. Our bodies will grow transparent. We will enter each other like walking through a door, until at last we come to an end of the picture world, a world where we are also pictures. Our movies and photographs, will they help us understand our last place, teach us how to die?

Hoolboom works in an essayistic rather than analytical mode. Onto a confabulation of images, he overlays his own meditative narrative on living and dying, appearing and disappearing, remembering and forgetting. These are no binary oppositions but states that pass into one another so that past and future, as well, may interchange and one can live backwards as well as forward. The image does not just record the past photographically, as if a memory; the image precedes us from the future as we advance in time to it. This is the sense in which the child said movies were prophetic of his future.

In film we encounter not the image of reality that takes us back to the world but the reality of the image that takes us out of ourselves. The image is something we grow into as the contour of our life; our life takes on the shape of an image, but not necessarily as a body. At the time of the birth of cinema, the philosopher Henri Bergson wrote that all matter is an aggregate of images. We do not perceive matter mentally as if a photographic representation; “if photograph there be, [it] is already taken, already developed in the very heart of things and at all the points of space.” Perhaps it took the invention of film to realize the heart of the matter. Based on the archive of a century of film images, Hoolboom’s The Invisible Man restores this condition to us. Stripped of its stories and narratives, film, our common picture world, is where matter dissipates and bodies disappear. Film is the doorway through which we communally pass insubstantially, as if we are always and only already nothing but images. We are what we behold.

Mike Hoolboom’s Invisible Man between the art gallery and the movie theatre

Book published by the Art Gallery of York University, 2009

5.75×8 in, 144 pp, 12 col/14 B&W, softcover

ISBN 978-0-921972-52-5

$20.00/$17.00 with AGYU Membership

http://www.yorku.ca/agyu/archive/archive/p2009_hoolboom.html

With the proliferation of digital projection, the presentation of moving images in art galleries has exploded exponentially. In the process, the relationship of experimental film to the gallery circuit has shifted dramatically. This volume, coming out of Mike Hoolboom’s 2004 exhibition at the Art Gallery of York University, is a series of essays and conversations between artists, curators, and programmers that delineate the complicated path from the white cube to the black box.

Projecting Questions? by Dagmara Genda (BlackFlash, Winter 2010)

Projecting Questions? begins as a challenge, from both Philip Monk, the director of the Art Gallery of York University, and Mike Hoolboom, a Canadian artist working in film and video. Why are video installations so awful?” Hoolboom asks. Monk responds by inviting him to make one for AGYU. The result was The Invisible Man and its accompanying publication that covers the ideas framing the project but does not function as a straightforward catalogue. Its readability is not only due to its variety – the book is comprised of interviews, essays, blog excerpts and conversations – but is also carried in large part by Hoolboom’s very immediate and engaging writing.

The content is framed by Hoolboom’s chagrined “complaints” (which is also the title of the last essay) ”I know, I know, it’s a hateful way to start,” he writes as he launches into a list of video installation’s many flaws, from its dull fidelity to one idea and monotonous repetition to its firm rejection of any filmic strategy. Monk’s response is “Paint It Black,” an essay examining the uniqueness and merit of video projection, and most specifically the work of Canadian video artists Rodney Graham, Stan Douglas and Douglas Gordon. Monk makes the claim that if film was about movement, then video projection is about time. It reorders temporality in a way that removes it from film’s persistent present. After, Hoolboom presents a self-interview which is a revealing peek into the thought process of the artist. Later he laments that so many video works are slaves to the “idea,” forsaking “emotions, stories, flow.” Monk sums up their conversations quite well when he notes that Hoolboom lobs “poetics” to his “rhetorics.”

Projecting Questions? also consists of a more traditional essay on Hoolboom by Chris Kennedy and a conversation between Hoolboom and Yann Beauvais, a French filmmaker. Included as part of the project is also a website link to Steve Reinke’s audio interpretation of Hoolboom’s films entitled Hoolbus.

If I cannot characterize Projecting Questions? as a catalogue, I might be content in saying it functions more like a website. This is not only due to the fact that part of the book is a reprinted blog, but because it slips between images, styles, poetry and speculation with relative ease. It models itself after the way we might browse a web site, hyperlinking from one idea to the next, chasing each available tangent. As a traditional publication, it comes to read quite differently than a linear book. Rather than build an argument or a narrative, it guides us through an idiosyncratic passage of thought and speculation to reveal the dynamics behind The Invisible Man’s conception.

Mike Hoolboom and The Invisible Man: Gallery Review

The Iconic Canadian Filmmaker’s First-Ever Solo Public Gallery Show

by Jon Davies

The show The Invisible Man at the AGYU was Hoolboom’s first solo public gallery show in a career lasting twenty-five years that has placed him in the pantheon of Canadian experimental film greats. The Invisible Man is a conceptually tight show that rewards multiple viewings and the patience of spectators who remain seated throughout the projections. The three Hoolboom pieces on display demand to be seen from beginning to end (which is of course possible, but not encouraged, by being looped) as they are nothing less than philosophical treatises on the twin worlds of reality and images, the image-world given the short-hand designation of The Movies.

In the Future, a short amuse-gueule in the gallery’s entrance, is both a premonition of what is to come and of what now seems to be Hoolboom’s primary interest: the impact of cinema on our psyches and life-worlds. This investigation can be found resonating throughout his work, which takes on other major themes such as the body, memory and history. In a few short minutes, it neatly sums up the questions posed by the show, and uses the evocative, careful juxtaposition of clips culled from narrative films and other sources and original footage to illustrate—either directly or obliquely—Hoolboom’s elegiac text, which I will reprint in its entirety:

In the future

each moment

will be photographed.

Doubled.

Our bodies will grow transparent.

We will enter each other

like walking through a door

until at last

we come to the end

of the picture world.

A world

where we are also pictures

Our movies and photographs

will they help us understand

our last place

teach us

how to die?

For Hoolboom, the movies are an immensely powerful and influential force in the way that we interpret our own lives and the very fibre of the world surrounding us. And no one is more attuned to the image-world than Hoolboom, who mock-solemnly describes in Imitation of Life how he was a child engineered to have his entire body be an opening—an orifice to absorb the world’s representations—by his father, a mad scientist (this accompanies a scene of Rotwang’s lab from Lang’s Metropolis ). To approach these work you have to be willing to accept a high degree of polemic: Hitler will be compared to a movie star, our society will be dubbed “the children of Fritz Lang and Microsoft,” life and death will be writ large on the silver screen. For Hoolboom, a Person with AIDS, the stakes are immensely high: in a talk at the Art Gallery of Windsor he claimed that the reason so many people are dying of AIDS right now is that they are not part of The Movie, they are left out of the realm of representation and consequently might as well not exist. These films can be read as eulogies, and with Hoolboom’s romantic temperament, they have a much more lyrical beauty, visual grace and—dare I say it: poetry—than one finds in most other works of essayistic media deconstruction.

In the sublime Imitation of Life —a rich title if there ever was one—Hoolboom’s voice-over, spoken here in at least three voices, is subordinated to the narrating role of the written text, which also carries the argument of In the Future. (Both of these are parts of the feature length anthology Imitations of Life from 2003.)

Imitation of Life begins with a literal representation of the title, a montage of images of human conception, the beginning of a human life mediated through cinematography. These shots herald a haunting evocation of a wide range of compelling—if not exactly fresh—ideas about the cinema and the image-world in general and their effects on consciousness: that the cinema—especially Hollywood—is doing the work that dreams once served; that any imagining of the future from the “species” of film called science-fiction is more accurately a representation of our contemporary society (and that recognizing our already existing dystopia will always be postponed to the future); how we are always engineering a world based on our images of the selves we like to consume and consequently become. Hoolboom suggests that the movies are trapped in an endless cycle, doomed to repeat the same stories over and over again, mourning but never learning, masking the “endless cruelty” that we are capable of meting out on real bodies. This world of fantasies, of lost possibilities and imagined but impossible outcomes, is the only thing that stands between us and “our desire to destroy everything.” We can infer that Hoolboom’s work is not necessarily an attempt at new stories—his work stays in the domain of recognizable, even conventional forms—but to provide a space of reflection and meditation in the gaps between the images, in their reconstruction in different “fringe” narratives. This is weighty stuff, and the dream-like piece is accompanied by a suitably droning, haunting soundtrack.

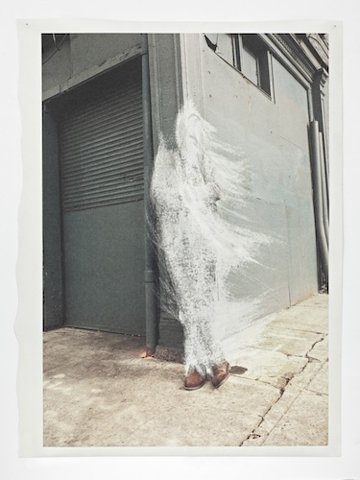

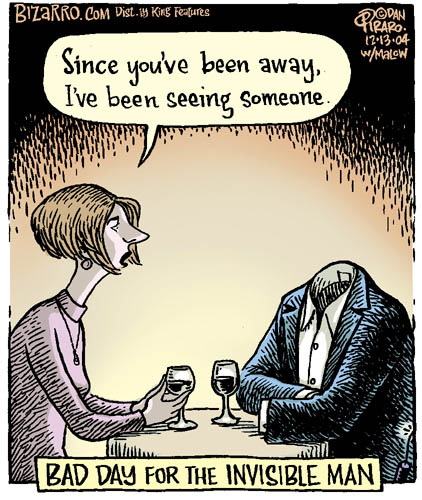

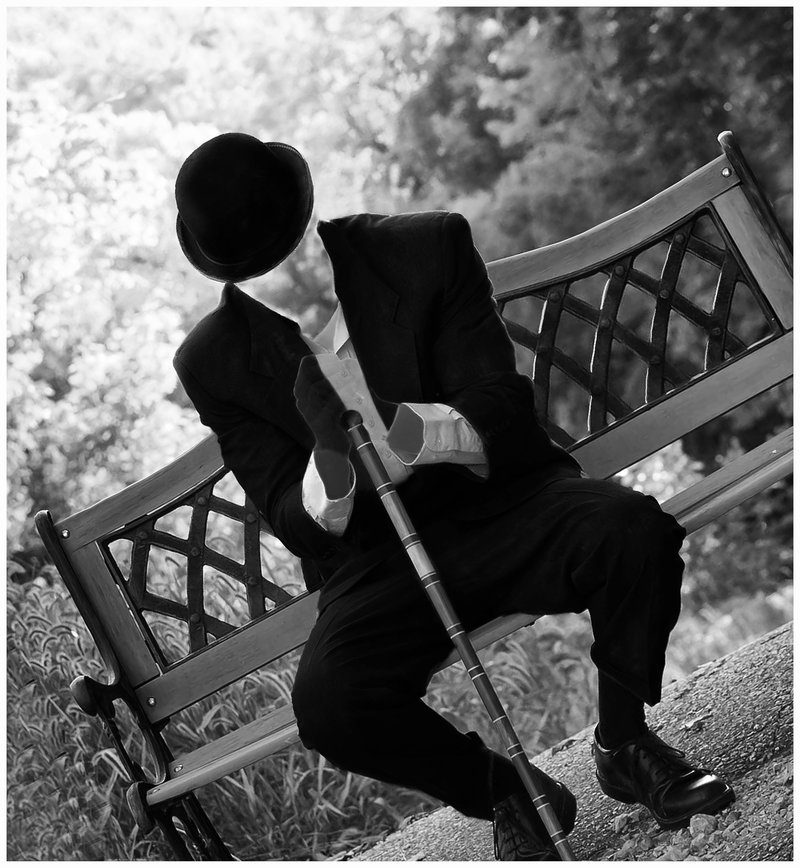

The eponymous video installation in the central chamber of the gallery, made especially for this exhibition, begins with a humourous, Dorian Gray-esque conceit that results in a quintessentially Hoolboom double-take. His own, adult male voice claims that we was born an old man and went through life losing wrinkles, getting younger, devolving. Hoolboom is in a curious kind of dialogue with a younger man who claims to be Hoolboom’s “writer,” repeatedly emphasizing that he wrote the script of Hoolboom’s life, that he controls his actions. This writer is the creator of the cinema, the image world. Here the movies are a superficially benevolent but ultimately violently prescriptive medium that initiates us into the world: teaching language, teaching vision, teaching values. We are all born into a script that has already been written for us, and our agency is largely illusory. This piece has more original footage than the others, with time-lapse images of the passing of light in interiors and the shifting of tide water in a harbour. Through these images of light and flow Hoolboom sought to craft a “birth to and as film.” The logical end point for this figure born old and getting younger each year is to become invisible, to merge completely with the image world, losing identity within the “ocean of personalities” on offer, and so we are given a montage of scenes from different invisible man films. Through what superficially appear to be kitschy special effects and the low genre of the monster movie, Hoolboom is able to express the total dissolution of spectator/citizen—or is it artist?—into the media to the point that subjectivity is completed wiped out. We all move further and further from awareness, the violence of the image world eroding the awareness and sensitivities we had at birth, represented by Hoolboom as an elderly, weathered figure losing their understanding of the real world as they go through a life scripted by another, the act of “forgetting mistaken for happiness.” The most startling moment comes from the seamless insertion of an invisible man’s footprints in the snow into some iconic shots of Kane’s childhood home in winter from Welles’s Citizen Kane. Overall, however, this piece lacks the same power of the other projections, which could be due to its slightly lazy over-reliance on clips of young 1950’s British lad Bud from Terence Davies’s The Long Day Closes, itself a transcendent masterpiece of movies-as-life.

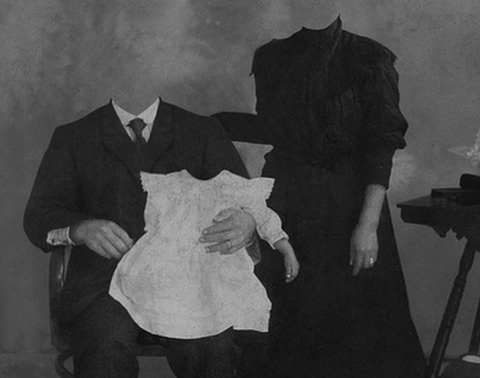

Facing this projection is a silent techno-monolith: three monitors depicting, from top to bottom, a series of leisurely strolling people captured against the background of a luminous blue sky, superimposed images of underwater footage (a motif in The Invisible Man), medical and science footage (which mirrors the opening shots in Imitation of Life) and others, and, at the bottom, a construction crew at night working on train tracks, illuminated only by the sparks of their equipment and some car headlights against a pitch black sky.

This is perhaps the least successful aspect of the exhibit as textless, voiceless sculptural installation is not really Hoolboom’s forte, not to say that he succeeds more with language than with images, but that this monolith seems to insist on a level of importance and meaning that its content does not adequately deliver. It does not contribute nearly as much as the films do, and seems like a concession to the idea of doing something specifically for a gallery setting, when in reality, the works on display would communicate just as effectively in a theatre.

Darker Side of Invisible by Fannie Sunshine

(Originally published in The Weekender, Sunday, November 28, 2004)

Death surrounds us. Whether it is a close friend who has died, or a friend of a friend, no one can escape the end. In his first solo exhibit in a public gallery, The Invisible Man, Toronto filmmaker Mike Hoolboom tackles the morbid subject through a montage of images drawn from Hollywood film, found footage and home movies.

His exhibit, on display at the Art Gallery of York University until January 30, overlays a meditative narrative on living and dying, of living forwards and backwards, of remembering and forgetting, where matter dissipates and bodies disappear. Hoolboom’s exhibit is made up of various scenes played out on six television screens at the Keele Street and Steeles Avenue gallery. Al the images are significant to the life cycle, he said Wednesday during the opening reception of The Invisible Man.

“While some people experience death from relatives or friends, all of us are witness to thousands of deaths in the media, it’s inescapable. Every image in this exhibition features people who are on their way to death.”

One screen shows the image of an old dying man and his last thoughts. Two voices tell the story of the man’s life-one voice expressing how he is today and another from when he was younger. “He’s going on a quest,” Hoolboom said. “He’s comprised of pictures that already exist, though there’s something missing in his life, but what is it? The voice of the child is his voice, when he was younger, the prophetic voice which announces the last trip he is about to undertake. The movie is about a father and son who are the same person.”

Three small televisions, set up on top of each other, depict different stages of life played out through various images. On one screen, three males of various ages are shown walking to no particular destination, which is intended to showcase different stages of life. The second screen shows images of organs and blood and the third depicts a man working on train tracks. “He’s making his way through life along these tracks, giving off sparks, a moment of humour or sexual contact, but mostly he is repeating, following his line. He’s isolated and alone.”

“The Invisible Man is a biography constructed out of moments of the picture world. It looks like the end where the skin stops, but our flesh is a projection screen for pictures we share with one another. We exist in each other. I hope something of that sharing emerges from people’s viewing.”

Art Gallery of York University Critical Writing Award Winners 2004–2005

Mike Hoolboom: The Invisible Man by Claire Eckert and Mike Vass

Berthe: “When did the gaze collapse?”

Edgar: “Before TV took precedence.”

Berthe: “Took precedence over what? Current events?”

Edgar: “Over life.”

Berthe: “Yes. I feel our gaze has become a program under control. Subsidized… The image, monsieur, the only thing capable of denying nothingness, is also the gaze of nothingness on us.”

– Jean-Luc Godard

In the exhibition The Invisible Man at the Art Gallery of York University, artist Mike Hoolboom deals in moving images. Predominately culled from cinema and patched together with home movies and other found footage, his montages are overlaid with music, text and voice narration. The work situates, and is situated in, time through an engagement of the body and a dialogue with film. As a distinct currency, these images are relational and shared, forming an assortment of stirring relationships between bodies and screens. These screens extend beyond the blank spaces on the gallery wall and invite us to re-imagine our relationship to the larger world in terms of an interchange of images.

In the gallery space time is durational and experiential; the videos loop on monitors and large screens, immersing the viewer in a world of moving images. Structurally absorptive and physically lulling, the images and sounds are internalized by the viewer to affect the body. Our bodies temporarily dissolve in a sort of body-amnesia, and a reversal of the visual occurs, as insinuated by the exhibition’s title. We become invisible, dematerializing as the images wash over us and as the sound reverberates through us. Seduced into the “black box” 1 by the rhythmic monologue and the glow of the screen, we act as we do in movie theatres: we sit silent and watch, waiting to be entertained and affected (although in the gallery we have the easy option of getting up and leaving). Hoolboom coyly suggests that we will eventually forget what we are waiting for, and will just be left sitting there, silent, watching.

This coy suggestion introduces a slight unease (as well as a sly sense of humour) as we suddenly become aware that something strange is happening to us, and that it happens to us whenever we give ourselves over to a work of images. This transforms our experience of the works; suddenly we realize we are invisible. But this is not ‘losing ourselves’ in the way we might like to imagine we dispel our cares at the movie theatre, nor are we being ‘transported to another time and place’ in the escapist sense that cliché suggests. We realize that, as bodies, we are not absent: we are dynamic screens. Paradoxically this realization makes it impossible for us to take our presence in relation to the images for granted. We recognize that, as viewers, we are permeable; the images flow into us, onto us, through us and out of us, and there is no separating these processes. When the works are viewed as installations in the gallery space, as with The Invisible Man, this aspect takes on an even greater significance than if the works were seen in a more conventional cinematic setting.

Hoolboom’s work implodes as it is watched; each image regresses and layers onto itself and others, just as segments of time—the past, the present and the future- seem to collide and collapse into each other. This flattens time, turns it into images. Paradoxically, the dehistorized images are relegated to the past, to the history of cinema, while simultaneously shaping, and being shaped by, our collective experience of the present and our imaginings of the future.

As both a “vehicle for remembering and forgetting” 2 Hoolboom’s apotheosis of moving images nods to Godard’s discursive montage Histoire(s) du Cinéma (1989-98), expressing both a deep love of images and a lurking dread of a world made through movies. Godard’s work is an elegy for the lost possibilities of both cinema and History, a mourning for an irretrievable past; Hoolboom takes this to the next logical step and mourns the loss of an irretrievable future.

One of Hoolboom’s strategies in addressing the future is to position his works in a peripheral, ironic relationship to science-fiction. He does this because science fiction is a genre that explicitly explores the uncanny experience of being lost in time. The Invisible Man is science fiction that speculates not about what is to come, but about what will have disappeared, not on what will be, but on what will no longer be. Like Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962) the works in The Invisible Man are science fictions about memory which try to imagine what the future will be like once it has become the past (the title of Marker’s recent Remembrance of Things to Come could serve as a summary of Hoolboom’s project). Marker and Hoolboom are both cinematic essayists who explore the tension between the lived experience of time and observed, historical time. Like Marker, Hoolboom understands the sadness that is inextricably bound to the cinema’s seductive ability to collapse the past, the present and the future into single sustained moment.

As Hoolboom turns toward the future in this way, his tone becomes more ambivalent than Godard’s. While Histoire(s) du Cinéma is both openly subjective and pedagogical, the works in The Invisible Man are more difficult to pin down. The voice-over and text address us intimately, and yet there is something distant and elusive about them. We are never sure where this narrating voice is coming from. Who is speaking to us? Who is guiding us through this image world? The narrator is present but invisible, as we are. The effect of this is that the works seem to be speaking on our behalf while at the same time addressing us, at once speaking to us and through us. But what are they saying? What are they telling us? A story? A confession? A warning? A history lesson? A prophecy? The mood is often elegiac and melancholy but never truly nostalgic. It is also oddly hopeful, or at least open to the future. One of the most impressive features of Hoolboom’s work is that it is both precise and open-ended. Hoolboom seems to accept our fate of being lost in a world of images; however, he does not seem sure it is a tragic one, although there seems to be no question we are losing something. But in loss, there may be gain.

Notes

The epigraph is taken from Godard’s In Praise of Love (2001)

1. Philip Monk, “Paint It Black: Curating The Temporal Image” in Prefix Photo (Number 9 , May 2004): 15.

2. Mike Hoolboom, quote from work in The Invisible Man at the Art Gallery of York University.

Philip Monk curates Filmmaker Mike Hoolboom’s inaugural museum show, The Invisible Man, at the Art Gallery of York University by Carla Garnet (2005)

Over the past forty-five years video as an art form has expanded to embrace single-channel videotapes, video sculptures, cinematic installations, plasma screen presentations and multi-channel DVD projections. Gallery installations by independent film and video producers have precipitated numerous viewing innovations many of which are employed by Mike Hoolboom’s 3-part installation entitled TThe Invisible Man, curated by Philip Monk on view at the Art Gallery of York University.

The gallery setting allows this filmmaker’s complex combination of camera images to create associations between time and space and the viewer’s body. Hoolboom’s exhibition asks that the viewer become involved with content and context, requiring visitors to reflect on their precise location in relation to the work’s locus. The Invisible Man, illustrates a statement by Margaret Morse (author of Video Installation Art: The Body, the Image and the Space-in-Between): “It is the visitor rather than the artist who performs the piece in an installation.” For that reason context is critical to Monk’s curation of Hoolboom because it is the gallery that allows the filmmaker’s work to function more like sculpture than film.

Upon entering the AGYU our attention is drawn to Hoolboom’s black and white DVD-loop, In the Future, created from a montage of Hollywood film, found footage, and home movies. In the Future is presented on a flat, horizontal, plasma screen that is cleanly inserted into an otherwise unblemished white wall. The audio component of the first work disarms the visitor, who is still struggling to un-encumber their bulk of winter’s necessary clothes. It is a child’s voice that breaks through reverie with, “Last night I had a dream: that the movies I had seen even in the womb were a prophecy. They were my future.” Beleaguered by more layers to be peeled off and then to be later reapplied, gallery-goers are reminded that while the artist’s bodiless articulation has the power to break through private day dreams, as spectators, we will have to take in Philip Monk’s curatorial presentation as corporeal beings. Driving the point home an AGYU attendant hands out the exhibition map, propelling viewers forward.

Mike Hoolboom is primarily known as an experimental filmmaker who urgently conveys the contemporary relationship between life, death, sex and the movies. In this respect, the AGYU’s show of Hoolboom’s oeuvre, The Invisible Man, is no different. Without directly saying as much, Monk’s installations of Hoolboom’s projected works ask us to reflect on several of Walter Benjamin’s seminal questions. How cinema has altered our relationship to life experiences? What are the ramifications of film (and photography) on art? Has mechanized copying freed art from its reliance on the ceremonial? Has the purpose of art been inverted? Has cinematic experience impacted on the optical parts of the mind that contain memories, thought, feeling, ideas, and the unconscious? Does the physical experience of viewing Hoolboom’s filmic work as installation interrupt the dream state often associated with the cinema experience and make us conscious of it?

In order to take in the next work, from which the show takes its title, the map tells visitors we must walk through a narrow darkened corridor into a sizable room where a projection of The Invisible Man competes with a 3-monitor tower for our attention. As spectators we are conflicted, which way should we look, at the luminous projection or at the three small televisions? Our attention races between the cinematic black and white projection that occasionally blooms into living colour, and the phallic television tower. The artist’s voice intermittently pierces through the hypnotic passage of images and symphonic soundscape. His projections refer to themselves, light projected through windows, doorways, rising and setting with the sun, forged in the heat of a volcano, shone from lamps, flashlights, nightlights, expunged into darkness and reborn as daylight effectively turning the gallery into a giant strobe and beating heart.

Informed by the map, viewers are made aware that there is one more Hoolboom work. We read that this cinematic piece is a meditation on living in the fields of the future/past, accessed through the shared picture world of movies, where substance dissolves and bodies evaporate. It is entitled Imitations of Life . Accordingly, visitors move through an institutional door into another dark space. This action functions as a double crossing over from a projected threshold through an actual one, the double entrance implies a double exit.

A word caption emblazes momentarily across a large flat light-informed surface. It reads, “IN THE ‘TERROR TO REMEMBER’ HOW WILL YOU INVENT THE FUTURE?” Witnesses are keyed to think, “there are so many cinematic versions that already exist.” Science, cinema, and art merge on screen and in the synthetic space between the viewers and the viewed. The installation is a loop that plunders the body of cinema for an epic that contains a dominion of dislocated fears and dreams, a place to imagine a future that is already here and that we must pass back through in order to reach the end/beginning. In the process of taking in Monk’s presentation of Hoolboom’s installation, gallery-goers are transformed; our unconscious thoughts arrive on the surface.

Video installations on the whole are as much about technological change as they are about changes in artistic fashion. As soon as artists became interested in video, they tried to work with the image as a sculptural element, but as a filmmaker, Hoolboom has been resistant to exhibiting in galleries, so it is important to acknowledge that The Invisible Man results as a consequence of Monk’s curatorial intervention. In this exhibition, the gallery-going experience functions as a passage. If indeed, we are sleepwalkers as the show implies, it is we who have performed Philip Monk’s sculptural installation of Mike Hoolboom’s The Invisible Man.

The Elegy of Blindness

A Review of The Invisible Man

An Exhibition of Films by Mike Hoolboom

by Bob Black

“Then one day this infirm body stirs in the womb of God.”

–Marguerite Duras, The Ravishment of Lol V. Stein

“Mortals and immortals, alive in their death, dead in each other’s life .”

–Heraclitus

We are blind stone.

We did not begin that way.

In our volleying pre-birth, we were abundant, a radiance of sight and light. Light combing its way through our mother’s outside skin and tunneling. Light in a home of shadows cantilevered our tumbling, blood gestured our initial patina, temperature shifted its circumference as we absorbed our growing life: food, sound, wash of oxygen, genes which penetrated our chrysalis skin and we began to absorb this flooding life through the umbilicus of our seeing skin. We were born with a corona of sight: the translucence of our initial skin. The embryo a star-child weaned on light. Was this our first affliction?

How is it that we began in an iris of darkness surrounded by so much sight and then, as if some perverse end run, we began to loose it, precipitously? Our largest organ, skin, erupted in the birth bubble as sensory being allowing light and sight to enter and register life, first in the swelling swarm of fetal life, later in the direction toward light. Much later, as sentient beings we could recall or define this luminous beginning. Do the films we gleam in science class or in motion picture theatres, depicting this burst of physical creation, remind us of some misty curtain of memory or are we fooling ourselves: images as false lanterns compensating for our forgetting? Why is it that we so often fail to acknowledge it, though we have seen the films and images our entire blind life? When we did not know, those initial nine months, we saw. Now we know, but can we see, really?

We tell ourselves we see and still we fail to remember: we cannot recall the life inside nor the passage through the first opening. We’ve constructed a cosmology of images to attend to this lacuna. Our philosophies have tried to instruct us to see before we understand or believe. We have constructed a lexicon of images to stitch together the gaps of our lives that we’re forever running backward in our memory. We attribute sight to ocular orifices. But in truth, sight began more democratically: across the entirety of our bodies. How now, flooded with so much imagery coupled with our dictatorial enslavement to what we imagine is our Rosetta Stone for understanding, have our eyes so elegantly failed to see? The kingdom of sight began wider than in the cornice of our small eyes. What has happened?

We age and metamorphose: become increasingly unsighted. We can recall, like an alphabet or algebra, all the images, real and imagined, manufactured and stumbled-upon, which have lit up the skulls of our memory, but have we admitted to our blindness. We dream in images; we speak in images, we narrate and navigate and negotiate everything through what we see or believe we have seen. Is this really seeing, or something else? Do films bespeak knowledge; do images bespeak understanding, does sight guide seeing? Are we relying upon vapors, the wavering scan of an oasis in the middle of the desert, is anything there now. How ironic that motion-picture films often use watery imagery, those slippery-looking serpents of peeling light to represent slippage in sci-fi films. Recall Terminator and the watery transformation. Don’t these computer effects look identical to heat vaporizing and rising in a desert: false water ahead. Where is our sight?

Abundant, we are born seeing and then the descent begins: our transformation. An embryo skinned in a sheath of transparent, translucent light and then what do we become? Our metamorphosis, from the entering of the outside toward the exit from the inside. Are we thrust into this waking life, from between our mother’s legs, already loosing sight and seeing skin? Is this why we require so much from the tiny moving portals in our skull?

“In the future each moment will be photographed, doubled. Our bodies will grow transparent…”

But, we were already born transparent and we slowly grew in reverse. We became opaque. Do we add to this opaqueness through our unquenchable thirst for pictures, movies, sight, or is our yearning and incessant image-making a small, quivering hope for some reunion, a returning to that which we once were? Can we capture this; elude the terrifying angels of our blindness, through constructing more and more. The shadow’s on the wall of Plato’s cave: the first newsreel, silent blockbuster, television commercial, internet ad, its all there flickering as we cower in the dark. It is all an elegy, is it not? Are we, indeed, preparing ourselves to return to our first beginning, our gradual disappearance. Have we, preternaturally, understood that images and movies are our embryonic skin projected outwardly? As Mike Hoolboom’s film Imitation of Life asks, have these images prepared us to learn how to die? Given us sight?

I am watching Mike Hoolboom’s films in a small room at the Art Gallery of York University and my skin is reawakening and my eyes are closing. For a moment, there is hope and a peek of a dream: to see again without the reliance of sight. The images flicker like my mother’s blue-red blood against the uterine wall. I hear sounds and howls and heartbeats. There goes another image from another film or television commercial or documentary or imagined image that I have stitched together from my own years of visual preoccupation. Is Hoolboom’s films, an ersatz memory constructed of other ersatz memories (movies) from my own life? For a moment, I do not know whether to embrace his films as his or the visual soundtrack of my own memorized life, false memories, kaleidoscopic turns, tweezed sounds and all. How has this artist, using images that others have created, stitched together my own personal memory? It is not enough to answer this easily simply because he has used clips from films and movies and documents that I have also seen and swam through. There is something more going on than collective memory. Is something archetypal happening? Is this a manifestation of our genes?

Why is it that we are always asked this question: what was your first memory? We, as a species, are preoccupied with firsts. Is this not already an indication of something failing? What was your first memory: in your life, of a love, of a friend, of a new home, of, of, of? Why do we not ask, what was your first sight? What was our first sight? We saw in the womb, we saw when we exited our mothers into that first light. Yet, we remember none of it. In the morning, we open our eyes. Who speaks of what they first saw each morning after sleep? Do we even remember that moment, each morning, the very first, ever at all? Strange, is it not, that we cannot recall the most astonishing moment of our lives, the moment our eyes peered out from the vagina opening and reconciled this startling, unprotected world. Did shock and horror blind us then, or is it something else. Why of all the moments, which we wish to see, we’ll never know that ones we must need: the corona of white light as we spiral out from the warm inside. It has become a monstrous cliché, but the darkened theatre and the conical strobe of movie-magic light against the wall: there’s the trajectory that we cannot remember. Is this why we sit there, listless, starring hour after hour, year after year at films? First the theater, then the television, now the computer, and what will be next. Will we look at each other in the future, as Hoolboom suggests, with the same dim but fully imagining sight? Memories projected onto and from within skin.

Movie magic. Wells. Mirrors. A deluge of images. Am I, now, competing with Hoolboom’s sea-tide of images, staving them off with words as a way to write myself back to seeing? Hoolboom’s films are transponders: toward and away from words, wringing and ringing the viewer. Am I collapsing or is it simply the reel is running low. From The Invisible Man, a dog’s bark is reverberating through the stretch of dark road, I begin, after seeing the movie, to hear this same dog for subsequent days. Is it the dog, my neighbor’s, really barking or have I imagined this recalling Hoolboom’s film. There is a tether there. Do images remind us to pay attention to what surrounds or have they spanner’d inside us and replaced what is really surrounding with their own soundtrack which has become the external soundtrack of our lives?

I should speak about the work.

Mike Hoolboom is a hallucinatory filmmaker who has conjured up more than 30 films, although if you ask him directly, he will quickly dismiss this number. His work, like memory, is not about explaining or quantifying but rather describing and qualifying, shafts of rain elucidating the sound of a drip on tin. An exhibition of two of his recent films, The Invisible Man and Imitation of Life (a 10-part elegy/cycle) were exhibited fat the Art Gallery of York University from November 24, 2004 until January 30, 2005. The 1st chapter, “In the Future,” the 3rd Chapter, “Last Thoughts” and the 9th chapter, “Imitations of Life” from the film Imitation of Life were exhibited along side The Invisible Man. More hallucinatory Lacanian essay then “movies,” Hoolboom’s films are rivers of images and sounds and words and palimpsests of reels of footage. Constructed from a patchwork of films which span the time of movie-making, from Vigo to Goddard, from Eisenstein to Abel, from Griffith to Busby Berkley, from Tarkovsky to Ray, one swallows his films as a cross-breed, an encyclopedic opera of movie-making which includes Hollywood entertainments, scientific documentaries, television commercials, travelogues, vintage exploration footage, anthropological studies, discarded film, home-made pictures, and his own personally shot footage, all marsala’d together to serve up a cosmology of the world’s motion-picture images. By patching and shifting and stitching together beads of images, he is both tying up and loosening our collective perception. One of the hallmarks of his work is that there is not an hierarchical alignment of images: art films coincide with Drive-In horror flicks, B-Movies are strung into art films, documentary collides with found footage from the 19 th century, Discovery channel films walk with Microsoft television commercials. It is a collapsing of centripetal forces which, at last, reconstructs our own understanding of what we have not only already seen before but reinterprets what we believe we know.

An aggregate is a misnomer in describing the work. While true, the majority of the images in the films are appropriated, Kenneth Anger fighting with Sex-Ed films from the 40’s, Tarkovsky slipping inside of car commercials from the 1970’s, the remarkable quality of his technique is that his accumulated films reinvent the images that he has chosen to use, not only through their juxtaposition with different films, but strained by the entirety of the entire film he has constructed. The individual clips and loops and movies sprout a new bud. Will it be possible to see again (anew?) the films that he has chosen to cut up and breakdown, like a virus inside a cell, without thinking of Hoolboom’s films? This is the keystone to his remarkable work. The use of appropriated imagery is often hounded with weight and association. Most of the time, appropriated images are used as sly, one might say disingenuously coy, footnotes to add a measure of erudition or weight to a work. The wink-wink and nudge-nudge of the “I am so clever, can’t you see” variety. This is, in fact, not part of the experience of watching Hoolboom’s films, but the converse. His collecting changes the original images so that through his films the appropriate footage and movies gain a new weight or perspective, new humor or new grief. The original films uses have been changed by their new construction. It is rare when an artist can snatch a swatch of another artist’s work and reinvent the original piece, not through reinterpretation but through metamorphosis. Am I able to again watch the slow pan of the cinematographer’s Cyclops-eye pan, which marks the beginning of Goddard’s Le Mepris, without again thinking of Hoolboom’s use? Are Microsoft commercials really that sad? Even Vigo is reborn. Hoolboom’s films, like all films, are magic lanterns, but he is also a melancholic essayist, an Elegist. He is using and re-writing everything he has seen before.

Is not the ten-chapter song Imitation of Life a reinterpretation of Rilke’s Duino Elegies, beatifying and terrifying? Although the exhibition deconstructed this film, by separating three of its parts as stand-one loops, one begins to appreciate the mobility of the film when seen in its entirely beginning with the chapter “In the Future,” (the first film shown in the gallery) and ending with his ode to collapse, “Rain.” Are all these films and images teaching us, or are we reaching for them in order to scribble inside ourselves the memories and sight we have forgotten. If our collective memories, demarking our lives and relationships by the resurgent memory of films we’ve seen and shared with others, have become our personal memory’s DNA, it is not far off when these vapors, once implanted in our skins with microchips and carbon-based transistors and displays, our skin will be watched. We will transmit our memories, those which are mine and not yours, comprised of the same imagery, outside for the world to see. We’ve left the hermitage of the womb and moved farther away from quiet reflection to outward collective gesturing and detailing. Wait, your knee reveals the same memory of scar that I have, is that Hedy Lamarr?

Time is not a river, though we convince ourselves it is. Bergson, whose delirium was stirred by the sway of the snake of moving images, argue this. But time is much more physical. Rivers flow linearly, time is directionless and physical: can you describe the scent of red? Time can. Is there light? Imitations of life is a beehive of digestion begun with this question of how we make, remake, unmake memory and what is all the imagery moving toward. Is it an elucidation of our inevitable projection: thin as hair, we depart and spread wide upon the air. The second remarkable chapter, entitled “Jack” is nearly totally comprised of Hoolboom’s home movies of his nephew Jack and details the lessons that he has learned from his wild-eye’d nephew: seeing, or unlearning to see. Gorgeously photographed in high contrast, saturated light and tinted wildly between sepia images bordering on the color Osip Mendelstam’s dried bee wings and the winter-tongue of cyan skin. The footage that Hoolboom’s uses, and which he himself has shot, is remarkable not only for its carnivorous beauty but as a volatile juxtaposition between that which he has chosen to create (his creation-memory) and the images he has chosen to use created by others (our creation-memory). Besides their voltage, what is also remarkable is that most of the footage, which he shot (including the digital images we later encounter in The Invisible Man) all nearly border on sightlessness. Often, he violates a fundamental principle of photography: never shoot directly into light, especially sunlight. And yet, time and time again this violation creates a profound and insightful truth: a halo, an apogee of sight surrounds his subjects: a penumbra-figure (man, or boy or shadow or flower or veil or sight) surrounded by a corona of white light. Ironically his friend, New York filmmaker Tom Chomont (about whom Hoolboom has also made a beautiful documentary) described this halo of white light as the first sight, that which we see at the moment of our birth when we slip free of our mother’s body: a circle of rounding, defining white light. The truth is that these nearly broken, restless, saturated moments which Hoolboom has shot, and appear as if we the viewer were exiting our own wombs and seeing the world for the first time, are the images in which the viewer actually sees. There, are those what the world first looked like to us.

In those brief moments when Hoolboom is shooting into light, we begin to actually understand (possibly), though they disappear quickly in burst, flickers which make up a small portion of the entire film. And yet, they’re there bleeding into our memory hours later.

The exhibition required and encouraged mobility, to sift around the room, a toe kicking in a belly, skin already born of outside life. I tumbled inside because outside mobility, walking through a gallery and watching, is not enough to replace what has been lost from the beginning. My eyes close and I begin to weep for the sight I long to have, again awakening, but cannot recover.

Does seeing teach us anything? Do our constructed images remind us or blind us further?

Then there is his newest film, The Invisible Man. It is a long recaptured elegy of a man who has re-imagined himself a child who imagines that he is trying to re-imagine what was and is and will be his memories: real or film-imagined. Again, composed of a galaxy of divergent images, it composes itself upon a critical idea: do we program the films to teach us our memories or do the films program and reenlist our memories themselves. Are your memories real or constructed elaborations on stories you’ve seen or heard before? What to do with this widening and narrowing confabulation of images: breathe, suffer, ignore, pass away? Are movies prophecies or something else, necessary markers not of what is to come but what has already happened: we are not beginning to lose sight for it has already disappeared. Still, we are there, running through the field, away from the house, down the narrow country road, across the snow-stained beach, we’re chasing, as it recedes further and further away. Of is it chasing us? We are both of and not of what we have seen.

“In the future each moment will be photographed, doubled. Our bodies will grow transparent …”

Our birthright is sight, yet how quickly it dissolves and why does it diminish? What we know is that our brain develops later the ability to categorize and demark. Jack sees something on the horizon of the distance through the window, his eyes move away. We, born of the seeing membrane, will soon in a wondrous blink of nine months, turn our cocoon inside out: our skin’s sight exchanged for birth skin, parchment, cells, hair, a malleable wall that absorbs and shields but no longer sight. Protective, this skin, we are told. Sight exchanged for something else. We are now, not then, in darkness and spend the entirety of our lives raging against the dying of that light.

We are abundance. See how vast it is that you enlarge all of space. Can we learn anything from films, from Hoolboom’s investigations and mournful songs? Is it in us to learn, maybe not. But in the end, what alas is the flight away from sight toward memory? Is it not the recognition of our not-yet-dead flight? We conjure magic from tricks and shadows what is this continued conjuring. Is it because we deceive ourselves or because we really know that our heroic striving ends without gain and continual longing. We are stirred because we are at a loss.

Mike Hoolboom’s songs are spiraling, remarkably beautiful blooms. Close your eyes and let sight enter you again. Hoolboom has begun to recapture sight through the prism of film’s hungrily devouring blindness.

So then it is true. We come full circle. We began in sight, we lost our way, we end with the illusion of sight. But isn’t the first order of seeing the attempt to transgress and transcend the absence of sight.

Time washes away stone, even blind stone.

Thus we sing, blind or not, a knotted song which eclipses the reigns of sight.

Can you see?