Journal Entries 1994-1996 by John Price

“John Price makes small, delicious movies that are deeply rooted in his everyday life. He’s a journal keeper, both as a scribbler and collector of pictures, and often labours for years with small moments of footage to reconnect with the past’s distant shoreline. His work is lyric and precious and wounded, often partial and incomplete, offering shards not stories, tugging at the convulsive memoires of footage, the bursts of raw feeling that emerge from a moment, which each movie attempts to spin into reasonable forms, sometimes hopelessly. Impossibly.

Years past I was asked to sit on a university panel that would award John his master’s degree. He showed a long beautiful reel, much better than much of what was lamping up the screens in the name of the avant. Of course he passed, but what amazed me was his disinterest in making prints or circulating these pictures. It was a private practice, though slowly, and with the encouragement of friends (most notably Alex MacKenzie who ran his own micro-cinema in Vancouver) he finished them, though I suspect that nothing is ever quite finished in John’s mind. I asked if it would be alright to print up some of his journal entries concerning his work and he agreed. He’s living with Lea now in the junction district of Toronto, along with their new boy Charlie who hasn’t learned to walk yet, but is experiencing some serious time on camera.” (MH)

Introduction

I remember starting my first journal while working as a marketing manager for a small division of Bell Canada Enterprises researching radio communication systems for transit, ambulance, fire and police applications. My supervisor had been around the firm for (too) many years and it seemed that having a second cel phone installed on his lawn tractor, Thursday afternoon golf with Bell seniors and the disbursement of Blue Jays box seats among other execs was a greater priority than the development of a five year plan. Head office shut us down, laid me off and relocated my boss to another managerial position somewhere in Saskatchewan. At the time I was living in a suburb of Mississauga (20,327 Dixie Rd, unit 212) with an insurance salesman and a woman who believed her singing engagements at local Italian weddings would invariably lead her to a career in top forty music video. The journal was an attempt to make sense of this chaos and in conjunction with liberal doses of controlled substances and my electric guitar, deterred the occasional impulse while driving home to launch my vehicle through the restraining barrier at the intersection of highways 401 and 427 and Knievel it into the cemetery oasis below.

My journals recorded the dramatic irony through times of personal change. It is this documentation, beyond the capacity of my brain to access fragments of these memories, which remain an alternate forum of reconstruction.

The work to be presented at this thesis screening represents the genesis of this process as applied to film. None of these projects were script born, they were begun by loading a roll of film and reacting intuitively. In some cases the ‘entry’ remains as it was shot, 2:45 of soundless, unedited negative. In others, pieces from rolls recorded at different times and locations intersect. The primary focus is to document and explore the poetics, irony and sublime inherent to subjective experience.

This filmed journal approach has led to a hand made aesthetic, an experimental investigation into the way various photo-chemical processes interact with mechanical and optical elements to communicate a tone or mood. With each roll I become more sensitive to the effect critical choices entail. Focal length, diaphragm opening, film speed and stock, chemical process (high or low contrast developer?), negative or reversal chemistry, solarized or reticulated? Which positive stock should this footage be printed onto, how much contrast or saturation? Should the speed/framing/superimposition possibilities be explored through optical rephotography? These are questions of memory.

As much energy is devoted to working out the photographic character of the image and its relationship to theme as uncovering the place of the images within the structure. Some of the work is assembled and re-assembled many times, while some remains virtually unedited. I think most of it comes across as fairly rough and unpolished, but I feel this aesthetic is akin to the way we recall. Time erodes memory into amorphous fragments, reconstruction is equal parts fiction and truth. In any event, this is the way I’ve chosen to remember.

Films

Look/See/View/Watch

New York City, January 2, 1995

Even in small galleries like the Frick tourist throngs make the rounds filing past far away landscapes. They are in perpetual motion, eyes training from one canvas to another, chatting loudly in foreign flavours. There is always a small group hovering around the tiny Vermeers but mostly they take it all on the run, moving on up the strip. I find a less trafficked painting but can’t focus through the rumble, I hit Fifth Avenue with my camera watching them come and go wondering at the masterpieces displayed sans history, art object as inaccessible capital. Inspired or perhaps overwhelmed by dislocation the camera rolls up multiple exposures onto high contrast black and white print stock with a telephoto lens. After returning to Montreal I develop the four rolls and find the negative presents the world as I remembered it, exhausting and strange. But the questions which preoccupied me are nowhere evident. Drawing from the marketing research course I took while completing an undergraduate degree in Commerce I posed a series of questions which attempt to surmise through demographic and attitudinal inventories the nature of museum visiting populations. The insertion of these intertitles provide transitions between the unedited image rolls and engage the viewer on a more active cognitive level. The film is silent.

Wreck/Nation (12 minutes 1998)

part 1: Wreck

Fleming, Saskatchewan May 25, 1995

Third day alone, driving west to Vancouver. I passed the wreck not long after crossing into Saskatchewan, a twisted mess of iron on the other side of the highway. Half an hour after I watched the image recede, the memory of this apocalyptic tableau compelled me to turn back.

After loading the camera I approached the wreck without structural preconceptions to make a document, though its signs screamed metaphor. Overturned container cars bled flax onto the muddy soil, “Canada” logos rusted white and peeling. The violence of the event offered a vision of the nation’s future. With one shot left on the roll I emerged from the scene to notice perhaps the most iconic image of all. Flying tattered above the gas bar adjacent to the crossing where the train had jumped the rails was ‘our’ flag, its maple leaf savaged by a restless wind.

In Vancouver I developed the negative and made a print. Contrast was low so I made a second generation negative and printed again. With only twelve shots on the roll finding a structure was simple, and after a quick assembly I experimented with a bit of step printing, freeze frames, fades and superimpositions to ease transitions between shots and punctuate key moments. I was happy with the way the project had evolved: beginning with the first shot and ending with the last. All that remained was to shoot titles and a minimal sound design, or so I thought. Problems arose when I returned in September to Montreal.

part 2: Nation

Montreal, Quebec October 27, 1996

It seemed to be on every lip, addressed in seminar rooms and depanneurs, bathrooms and back alleys. I read both sides of the propaganda which appeared in our mailbox with equal cynicism, keeping it by the toilet in case of emergency. The parade of sinister clowns made it impossible to tell whether the province’s secession was motivated by visionary humanism or corrupt power mongers.

Out of a strangely compelling curiosity to be privy to a real (unmediated) show of ‘national’ unity, I attended a rally against Quebec secession. With my cynicism piqued, I arrived not unlike a curiosity seeker visiting a church, filled with the hope that somehow I would bear witness to something authentic and revelatory. A spirit within the people that would displace concerns over the way national identity was being media marketed. In an ocean of blue and red flags, waved furtively after each speaker, my curiosity was unrewarded. What I heard from that elevated platform was disembodied and lacking in emotion. Even so there were tears in the crowd and I wondered whether these emotions were motivated by a sentimental attachment to the mythological idea of Canada as the peaceable kingdom advertised in 1950s National Geographic magazines or the fear of potentially having to negotiate a new sense of identity without it. Regardless, it became a site of intense dis-identification. From the words that couldn’t be spoken to the ubiquitous news cameras objectifying the scene, to my own inability to feel part of a unified whole, Northrop Frye’s riddle “Where is here?” was supplanted by my own confusion over what is here. The construct of a nation? Through this frame, I recorded a document within the crowd, using hand-held telephoto cinematography, pixilation and superimposition to articulate my internal sense of dislocation.

I hadn’t had much luck developing my own colour negative so in an additional jest of irony, I had the now defunct National Film Board lab do it. As usual, they did an absolutely perfect job: brilliant, realistic colours which left me cold. There were, however, strong metaphoric connections to the film from Saskatchewan which I was tempted to explore. But the intercutting quickly damaged the personal tone of the film, it became a blunt instrument. After wheeling it out as an installation and several screenings I restored the original structure of the wreck and then turned to the rally. During the re-re-re-editing process the footage had been rephotographed many times, sometimes solarized, slowed down and sped up. I found the footage more fascinating hanging up on a ski pole drying than rolled up on a spool and projected. The current version of the film reflects this fascination, most saliently in the first sequence where a short abstract of flag waving is repeated in variations with each iteration possessing its own distinct photographic character. While it demonstrates the repetitive nature of the process, the flags’ shifting colour questions the basic construct of nation. A schizoid parade follows, politicians, media and a faceless crowd shuffle past in off-coloured worlds, a subjective projection not far from how I remember it.

The reconstruction of memory represents a continuing search for a possible future. But there is no end to questions here, technology has yielded to the forces of nature, and humanity remains as traces of a chaotic assembly. No conclusions. The referendum was very close, Quebec voted no, the nation was preserved. For now.

Remembrance

Vancouver May 18, 1994 and August 28, 1994

Montreal October 27, 1994

A good friend from Emily Carr College asked me to work on their film and that’s where I met her. She had been cast as the lead in a short about the media’s beauty myth. Like the director, she had been sexually abused as a child, and the shoot was very intense and draining, by the end of it I had learned a lot about emotional scarring. We become lovers a few months later.

Sometimes, no matter how much energy I expended, I was powerless to ease her suffering. A few days before she left to go tree planting in Alberta we set off for a picnic at one of the strangest locations around Vancouver. An eight kilometer long concrete sewage pipe by the airport which thrusts out into the Pacific Ocean. She often recalled for me a tragic heroine from the silent era, so along with lunch we packed a camera, a couple of rolls of black and white film, an antique bicycle, her mother’s wedding dress and some white powder make-up. With the help of my friend from Emily Carr and her partner, we shot, ate and chatted until the sun went down.

I processed the negative but had no facilities to make a positive, so for a long while I didn’t know what the images looked like. As the summer went on we talked and wrote occasionally and during her absence I began having doubts about my ability to continue working at the relationship. Also, there was an opportunity to attend grad school in Montreal, and after working as a camera assistant on an American TV show, I wanted more than anything to pack up my van and head east and open a new chapter. On the day of her return I found an enormous, radiant sunflower. I was unsure of how we would relate to one another after several months apart and was of two minds about wanting her to live in Montreal with me, but there remained the intense memories of our past. The doorbell rang at two in the morning and she appeared smelling of cigarettes and coffee. By sunrise she confessed to having had an affair and was consumed by agonizing guilt. I had actually talked to her about this guy I’d planted with the previous year, asked her to watch out for him and the unctuousness of his womanizing charm. Now I knew I’d be driving East alone. She asked if I still wanted to be with her and my silence answered. The following afternoon she drove back up north to rejoin the crew.

Each evening after returning from the circus of the TV shoot, I watched the sunflower’s steady demise. Some days it would make me smile, others provoked tears. The night before leaving Vancouver, after packing up all my belongings, I set up a couple of lights, loaded my roommates’ Bolex and began documenting the remains. As I filled the frame with dried out leaves and the drooping stem, clichés of love became deafening. Adding to the melodrama were a lesbian couple living ten meters from my window, loudly making love.

In Montreal I thought a lot about what happened out West, thankful that I was responsible for no one’s feelings but my own. During the fall I developed the sunflower roll and printed it along with the picnic footage. The editing process led me to all night cycles and journal writing in circles. I decided to buy a Bolex and shelve the project, shoot some film in the present which might provide a way towards a more defined relationship to the past.

A year later I watch the assembly and decide the film might function for others as an ode to the doubt and insecurity that grips the end of a relationship (many of the couples I know at this time are in the midst of parting company). I’m also interested in incorporating the first roll that came out of my new camera, superimpositions of walking and running through the ordered monuments of a military burial plot where I once made love. Intertitles were made and thrown into the fray. As a silent film the project went through twenty different arrangements but it still wasn’t communicating much about what I felt. During a visit with a friend in Toronto I found in his record collection a stack of 78s, mostly music for bachelors, love songs and country hits, which I thought would add a touch of romantic cynicism, at least humour. Two months of cutting to different songs and I’ve found the structure on which the film now rests.

Nine+20 (10 minutes 1995-2000)

Montreal, Quebec July 29, 1996

An extremely simple portrait of one of the most humble and deeply spirited people I’ve ever met. Two days before my closest friend, Michael Dolan, leaves on tour for Japan, we improvise the day together. Walking, talking, dancing and recording our way up Mount Royal. He moved from Europe three years ago to audition for LaLaLa Human Steps, a contemporary dance company known internationally for the intense physicality of their work. Wracked for months with self-doubt and the feeling he would not be able to endure the physical and mental torture of adapting to this new vocabulary of movement, his character underwent a steady transformation as his confidence and status within the troupe improved. I was fortunate enough to be able to spend time with him talking about our fears and the single minded pursuit of dreams.

His decision to leave a steady job as a welder in Ireland and pursue a career in dance has been without regret so far. It’s an issue we discuss at length. The investment of his life in a body which can sustain a professional level of performance for a relatively brief period of time, the persistent threat of injury, the fleeting impermanence of live expression. It has led him towards an appreciation of the present moment, one that I emphasize with and respect deeply. Though the path he’s chosen is of great concern to me and I often wonder how he will change when his ability to perform comes to an end.

During our day on the mountain I asked him to play a ‘character,’ a pensive walker who moves through the frame without any real destination. He spends most of the film doing just that, walking. After two and a half rolls I asked him to improvise a dance. We found an amphitheater-like setting and waited for a break in the tourist flow. Without any rehearsal the moment arrived and he busted a groove. He danced until ‘it’ was over and was still again. I put him into close-up for a beat and the film ran out. He wanted to try it again and work on the choreography a bit and I wanted to improve the camera’s fluidity but the site was suddenly overrun by people and the energy to re-take ebbed as we waited for the stage to clear. Like much of my work the film would remain imperfect, unpolished. We gave up and headed back down into the city to make supper and record an audio interview.

Knowing that we wouldn’t see each other for some years the conversation ranged widely. The tension between later and now. The desire to find a stable home. The conflicts of being in a relationship and maintaining freedom. A ninety minute cassette recorded on an old Walkman. After he left I developed the three rolls of black and white super-8 and printed them onto 16mm, then cut the interview to match an assembly. The grain of the footage and the tape hiss ambiance creates a sense of otherworldliness which resonates the presence of his spirit in my memory.

The View Never Changes (6 minutes 1996)

Pine Plains, New York September 27, 1994

St. Jovite, Quebec December 23, 1994

Late September I travel down to New York state to visit my father at his country home. After living out west for several years it’s the first time we’ve seen each other for several years. I wait in the doorway for an hour and a half pondering the difficulty we’ve always had relating to one another. He finally pulls up and explains that he was delayed at the dog kennel. He’s chosen today to buy a pure bred golden lab. He frees the puppy from the backseat and follows it around, cooing its name as it urinates over every inch of the garden. He rambles about champion blood lines, the internationally renowned breeder, the monogrammed pooch pillow on order. I don’t remember ever seeing him this happy. I watch in awe as he exposes a side of his character I never remember being privy to. Unconditional love is projected towards this little animal, as unaware of the world as a new born. I have brought two rolls of black and white super-8 with the intention of shooting “home movies.” My father had colon cancer surgery and as there is still so much of our relationship which remains untold, I wanted images over which I could contemplate, and perhaps torture myself with, in the event that his health deteriorated.

The dog remained the primary focus over the weekend, his name repeated thousands of times, fetching drills were enacted, and infinite inflections of the word “sit” were tried on. As they napped together on a lawn chair in the sun I climbed the stairs, unpacked my camera and stood observing them through a bedroom window. Shooting this scene brought on a sense of loss different and deeper than any I’ve ever known. Perhaps it was the realization that neither of us would ever have the strength or desire to express love for each other with the same zeal he managed for this dog. Maybe it was a reminder of the childhood I spent without him.

Back in Montreal I tried recording a voice-over of the journal entries I’d written that weekend but they only turned the film into a self-absorbed rant. Working on the film changed the way I saw my father. Seeing him day in day out on the editing bench with this puppy made it apparent that he had always possessed the capacity to love, though his ability to express it had been lost generations ago. His father was a naval officer during WWII who had been away at sea during my father’s formative years, and my grandfather’s father was a pulp and paper man who was completely absorbed in a desperate struggle with his two brothers to keep the family business alive. According to my grandmother the times dictated that mothers raised their children until they could be sent to boarding schools, then they were returned as adults. I began to see how my father had taken on these values and how this fundamental ideological gap separated us, and it was the same with many of my friends. As editing commenced again there was an overriding tension between this awareness and an undying urge to blame him for my own insecurities which I had long attributed to his absence during my childhood.

Christmas is spent with my mother who is nursing a sore tooth and while the rest of the family and step family goes off skiing, I have time to ask questions about the circumstances surrounding her first marriage with my father. The audio cassette fills with information about my birth, my father’s oppressively controlling tendencies, my mother’s affair with her psychologist, sordid details of their separation and divorce, and finally her clinical interpretation of his behaviour.

For months I attempted to distill this voice-over in a balance of compassion and rage. Vilification tempered with redemption. When it was done I cut the negative, mixed the sound and had an answer print made but each time I viewed the film with an audience the experience was charged with guilt. Obviously the balance hadn’t been yet struck, so I went back into the interview and re-edited. With the changes made and new ambiances and effects tracks I have not cringed in three viewings and might be able to live more comfortably with this memory.

Film, Video, Chickens: an interview with John Price (January 2012)

Mike: Livia Bloom, writing in “Filmmaker” penned these words: “An eerie mood pervades the smart, surprising Sea Series #10 (10 minutes 2011) by John Price, one of the only films in the 2011 Wavelengths experimental program at the Toronto International Film Festival explicitly inspired by world events. An intertitle explains that the film was made ‘10,190 km from Fukushima’ on May 21, 2011, two months after the deadly Japanese earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster, and a week after a leak was reported at the nuclear power plant that lurks just outside Toronto. Located on the shores of Lake Ontario, Pickering is one of the largest nuclear plants in the world. For Price, the date held the added significance of having been designated by a religious group as the day of rapture.

To obtain lush, saturated color, Price develops his 35mm and 16mm footage himself; he also used water from Lake Ontario, the star of Sea Series #10, in that film’s chemical process. The first movement depicts distant sailboats doubling and shifting under a dancing, blue-tinted sun; later shots show tiny dead sardines lapping at the shore, and richly contrasting black-and-white footage of beachgoers at play in Pickering’s ominous shadow.”

John: I went out to Pickering and shot close to the nuclear plant. It’s the tenth in a suite of sea movies. They were inspired by a photographic series by Hiroshi Sugimoto called Seascapes. Sugimoto: “Every time I view the sea, I feel a calming sense of security, as if visiting my ancestral home; I embark on a voyage of seeing.”

Mike: Why did you go out there?

John: I’d been listening to the radio and hearing reports about impending nuclear doom. And the rapture was supposed to happen on May 21, 2011, the end of all days, when the hand of God would scoop up the chosen ones. Lea and the kids had other plans, so I thought I might as well be on the beach to film the spectacle.

Mike: And then you took the footage home to your basement lab. Can you talk about what you did or would that be revealing your secrets?

John: There are no secrets, just chemistry. It’s a chemical chain that’s not designed for the particular stock I was using, so it opens up the stock to unforeseen reactions. What’s going to happen this time? Will there be an image? I like to work with out-of-date reversal stocks, and it can be hard to predict exactly what the results will be, and I like that. Sometimes there’s only grain, and maybe there’s an image way underneath all that, but even if you put tons of light into it, you can’t make out what is happening. Some people groove on that, but I’m not one of them.

Mike: You want to represent.

John: I think that’s the project. Representing what’s out there and seeing how these materials hold the experience.

Mike: Why is it necessary to work on film, now that even Kodak has filed for bankruptcy? Is the film image closer to the way you see or remember?

John: It’s a very specific way of working. What makes film specific? When you see a film projected on a screen it feels timeless, it doesn’t feel like the present day. As opposed to digital video that represents the present in a hyper-real way. When I shoot my kids on film, it feels out of time, like the moments could be decades old. Is it only nostalgia because super-8 (or 16mm) images have been codified as home movies? I’m not sure. Have we been colonized by our memory of memories?

Mike: In chemical cinema, there’s a space before the image. The image doesn’t appear before you see it, the way that it does in digital video. The image is already there, you point your camera and before you see it, the image is already in the camera. Whereas in photochemical cinema you have to make an approach, and set up the clumsy machines, and once the image is received by the emulsion you have to wait. There is time to process, to digest. There is an approach and a digestion. The digital image, on the other hand, exists in an uninterrupted present. Everything is already an image or is about to become an image. Whereas a film image has a before and after, a temporal succession, and exists in a relation of what Freud named fort und da. Near and far. The cinema spectator is alone with other people – both near and far. The image is small, and then is projected large on screen. The spectator also projects themselves onto the screen, and feels close and far. This back and forth movement is the relation between the individual and society, between past and present. Perhaps these are old fashioned terms.

The internet, on the other hand, is always there, you can turn your computer on and off, but the internet is still humming. It’s an endless surface. You can’t make an approach to the internet, and you can’t process it in order for the image to appear. Time is simultaneous, instead of successive. And this, I think, is a fundamentally political difference. Everything is already a picture in the digital world.

John: Yes, but what does it mean? How does that apply to where things go, how people remember, how people are?

Mike: You can’t remember if there’s only now. What creates memory is the space before and after the picture. All we have are archives now, which are a simulacrum, a prosthetic memory, an externalized version of memory. The nature of the new technology is to make everyone into an archivist. But ironically, it means that everyone’s archives will disappear because they won’t be readable or playable. This generation will leave very little behind and that will be good. Have you ever tried to retrieve files from an old computer? Imagine what those files will look like in a hundred years. Digital junkyard hieroglyphs.

John: That’s why I like working with physical materials that I can touch with my hands, and see them projected, knowing it’s not a one and a zero. You can see it, look at it, hold it. But if you break it down to the level of representation, maybe that’s not important. A sheep is a sheep, right? So why does it matter? It’s an ongoing question. Why document with this material rather than that?

Mike: Does working with film instead of video relate to your kids somehow?

John: Maybe it’s just habit. It’s a desire not to have so much. It’s a matter of distilling moments and having a particular memory. You don’t have a record of every memory, but a few survive that summarize and bear witness to the rest. Film provides a physical archive of what happened.

Mike: Like a relic, a shroud.

John: But how much different is that from a hard drive? A roll of film can burn up and so can a hard drive. Are they just different ways of making a picture? You can go to the cinema today and see a 2K projection and most people can’t feel the difference. In commercial cinema most films get digitized and massaged then spat back onto film if they’re going to be projected on film. Even if the original was shot on film, it’s already gone through the muddling/meddling process, so does it really matter?

I shoot with film partly because of the machines I have – my cameras and lenses do very specific things that I really like. If I had the latest greatest video and lens technology that would be OK, but the results would look like everything else, because everyone’s using the same stuff. And that’s not so interesting. I like to have an assortment of ways of looking at things. I have these long telephoto lenses that make pictures you’ve never seen before. It’s a different kind of searching.

Mike: You’re often busy shooting movies for various independent directors. How does this “commercial,” for-hire work relate to your personal movies?

John: When I turn on the camera for other people I want to make sure it’s about something, I’m not just making more pictures. For example, when I shot in the arctic I wanted to get at the pace of how things go, which is really slow. I set up a camera and framed an intersection in a small community and let it roll and watched what happened for ten minutes. That shot gives you more of a sense of how things go than taking a ten second excerpt of the shot and cutting it with whatever the movie is supposed to be about.

Recently I was in the United States shooting a documentary for Liz Marshall. I asked myself: what is this film about? It’s about how we do and don’t relate to animals. How do you show that? It’s all around, it’s everywhere. We go to New York and there’s a horse meat restaurant. There’s a high design store with antlers all over the walls. And then you shoot animals. I’ll just sit down here and see what happens with the animals. Some come up and look at you closely, so you have to get down and be with the chickens. Is that going to help people change their attitudes towards eating meat or becoming concerned about where their food is coming from? I have no idea.

Mike: Getting down with the chickens?

John. Yeah. Seeing pictures of chickens being chickens. What pictures should come before and after? Eisenstein please help me. But I think that’s Liz’s project – finding a way through the pictures in a way that speaks her story. And I’m happy to be in that moment and reflect on these issues because I have kids and these questions matter.

Generally I’m thinking in sequences… how the moments might be joined together but before that it’s about connecting with whatever is around me. I try to get a sense of what is in this moment with the camera. How do I feel right now and how can I represent that with this machine? That’s always the work, whether it’s for myself or for others.

John Price: Second Childhood

Precedents

The Canadian fringe has had a long engagement with the home movie, from Mike Snow’s Wavelength (a 45 minute zoom across his home), to Joyce Wieland’s Watersark (a film famouly made on her kitchen table, to the post-colonial narratives of Richard Fung (My Mother’s Place, On the Way to My Father’s Village). John Price has stepped into this tradition of the untraditional, collecting and transforming the sights and scenes around him, recuperating the stuff of everyday life as his material – the birth of his two children, the incessant passage of the trans-national railway just steps outside his front door, and rituals of masculinity (hunting, fishing).

Home Movies

Most home movies are staged moving picture albums. Getaways, birthdays and Christmas cheer events all stage the family. It is striking how generic most home movies appear, even as they aspire to show the intimate, the personal. How often they return, in reel after reel, to the same themes, the same looks, the same gestures (more presents opened, more squinting into the camera). This tendency was parodied in Steve Reinke’s Excuse of the Real, the first of his The 100 Videos, in which he proposed making a documentary which would require the use of home movies. “I would need some home movies, flickering super-8. I would use these as visuals. If my subject didn’t have any, another’s could be used. Everyone’s home movies are basically the same and it would simply be a matter of matching hair colour and body type.”

But unlike most home movies, John doesn’t deliver a sentimental shorthand, or perform the act of covering up. Instead, his camera is not afraid to encounter, to challenge, to witness both the wonder and terror of his children. There is certainly awe in his first glimpse of his newly born daughter with the good light running across her belly, and the placenta which is soon brought into the garden. But his daughter’s face is covered over in spots and hives, she is not a “traditionally beautiful” baby. Later on, interactions between the children do not appear entirely harmonious. Instead, there is an interplay of close/distance, of attraction and fear. When Charlie, John’s son, is shown a barnful of dead chickens hanging to dry, he is repulsed and fascinated. Charlie becomes the locus of a generational conflict as his grandparents try to draw him closer to the world of these animal deaths, while his mother intercedes to protect him. The filmmaker does not weigh in on one side or the other, it is more than enough to present these primal encounters.

Scale

One of the exciting things about John’s project is that he is intent on taking moments which are so very small — like his son Charlie eating a slice of chocolate cake on his birthday at the family’s lunch table — and then blowing it up very large. His shifts in scale elevate these acts and make them into something very different. I have sat, thrilling, while the leaves of the theatre frame open wide to admit John’s scope film View from the Falls. The clarity and size ensure that I am able to move my eye across the vast picture, and create a living montage. I am a breathing, blood pumping, editing machine, collecting moments across the picture plane, putting them together as I choose, according to my own design. Even when the frame is still (which is rare), the viewer grants it movement because of its scale. Part of the mystery of his work is the way John makes small things large.

Politics

Common wisdom states that families and art don’t mix. Who has the time to pursue the idle dreams of art any longer? Yet John has stepped into this traditional dichotomy between work and life (and while his partner Lea is everywhere present, he is very much a primary caregiver, days and weeks are spent with his kids, his priorities are clear). But at the same time as he is living, as his children are running and swimming and learning how to talk, the camera is turning, and the emulsion is shaking. Everything is moving, and somehow, magically, everything is moving together. The old dichotomies have been left behind, at least for now, and in their place there is an adventure of discovery. He is open to receiving what is around him, and he is busy using his many years of technical skills to make this possible without letting it stop anything. He finds a way to express his own fears and hopes and longings through his camera work, his daily living, and his chemical reinterpretations which condense a hundred looks into a single roll of film. He doesn’t feel the important things in the world are happening “over there” or somewhere else, they are happening where he is. How else but to understand this small-large cinema as a political gesture?

The Artist Says

“I don’t make movies from scripts… there are no actors… I shoot movie film like a traveller would shoot stills… as a diary or memory of experiences… travels… birthdays… christenings… break-ups… weddings… parades… holidays… good-byes… using old 16mm film and processing it myself is cheaper than going digital… the emulsion’s texture somehow communicates on an emotional level and the process fascinates me… editing is like organizing a scrapbook… it is a process of reflection… who you were when the images were recorded and who you have become and how you have changed… how everything changes… an intensive process of observation, meditation and reflection… I think it’s an attempt to communicate a sense of the richness of humanity… the theatre of the absurd… the fragility of past and present… besides, friendship and loving is the only way I know how to make sense of this place.” (August 2001)

The Story

This is the way we learned to tell the story of tradition and the individual talent. The artist burns with something raw and unspoken and necessary in their youth, and somehow it doesn’t manage to come out of their mouth. It is before or after language, or mathematics, or signs of any kind. It doesn’t live out there, instead, it is attached to the body, and to the body’s media extensions, its necessary prostheses. So the young artist learns their craft — whether scratching on pewter, or mushing clay in their hands. The first efforts offer a screened glimpse of that quiet burn inside that pushes the artist, hour after hour, to return to the studio, to the material, to the thing nside that wants to find its dreamed double outside. It’s only a story and yet. How many stories have I lived before now, and how many are left, waiting for me to step into their well worn shoes? And then the art arrives, ready or not, the burn leaves an impression hot enough to be shared, to be seen by perfect strangers. A light visible for kilometers, the brightest star in the firmament.

Second Childhood

John Price became a child again in the playground of film’s chemistry. He learned the difference between colour toners which worked into the shadows (the unspoken, the forbidden), and the tinters which headed for the light areas of a picture (the things which are too much looked at, the clichés which must be made new again). He was one of those handy men who knew how to fix things — plumbing errors, wiring judgments, small structures — he could look at a thing and know how it was made by the feelings inside his fingers. His hands knew the secret of how things that look solid and forever can come apart just like that. And how to put it all back together again. And how temporary that is too.

In-tuition

He’s a handyman. A handsome, curly-haired, soft-speaking man’s man happy to let his pictures do the talking. Even at the beginning of the beginning, back in school, where every step should be outlined in chalk like a corpse and then followed right up by the autopsy squad — the scriptwriters and crew members justifying the catastrophe of pre-production planning — he didn’t want any part of that murder scene. Instead, like so many men before him, he liked the feeling of leaving, he lived to feel the road rushing past him going fast nowhere in particular. He found that when he was lost, when he had run enough miles past his brain, he could finally swamp the storyteller inside, the one forever busy attaching itself to nearly everything around him (that street light is my street light, that bus driver belongs to me). Once he could let go of those stories, once he had run up enough miles, his mind would clear, and then he would be ready to begin shooting. In other words, to notice what was right there in front of him the whole time.

Clearing

“So writing involves some dashing back and forth between that darkening landscape where facticity is strewn and a windowless room cleared of everything I do not know. It is the clearing that takes time. It is the clearing that is a mystery.” (Anne Carson, Economy of the Unlost)

First Steps

John’s early movies found him running some of his found fragments through wide-eyed, and occasionally wide-angled, alchemical reworkings. There was a train wreck in Saskatchewan (Wreck 4 minutes 1997), a flag waving rally in Montreal (Nation 5 minutes 1997), a raging fire near the Coulee Dam (Sunset 2:45 minutes 1997), a hallucinogenic roller coater ride in Vancouver (PNE 2:45 minutes silent 1996). These are moments of looking, sometimes just single rolls, each subject to a single, delirious chemical refashioning that underlines the original moment of encounter.

Michael

Everything John made was fine, or at least OK, or at least yes, that will do, a pass, a workmanlike effort. Until he made nine + 20 (10 minutes 2001), the touching film about his friend Michael Dolan, a dancer who talks casually to John about his hopes as they stroll together up the mountain in Montreal. In the end, facing a future whose only certainty is that they won’t be seeing much of each other any more, Dolan breaks into a dance, very casually, as casually as picking up a pen or a spoon or a word because it’s the only thing that can save your life. The only way you have left to say good-bye.

Practice

But this exceptional movie was the exception, mostly John was laying down tracks. The artist steps up to the microphone and says, “Testing, testing…” They are steps along the way, part of a necessary passage. And then the catastrophic thing happened that is not supposed to happen to an artist, a real artist, the ones staring back at us from the magazine racks. Or at least, this is how the story goes. After the initial burn, the artist pours their wordless heart into makings of every kind, and then the burn is spent. These efforts may be noticed or unnoticed, they may bring gallery dealers and buyers and fame or nothing at all. Sorry for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Sorry for not fitting into the prevailing wind of ideas. (Most of us fit the economy of present ideas very well, but we don’t fit urgently. We are footnotes, another thing in a world already too full of them.)

Visibility, or the knack of being noticed, strikes artists like lightning. Randomly, here and there, once in a while. Luck has so much to do with it. And drive. Please don’t let them tell you any different. Talent? Sure, it’s always fine if you have talent, but talent is a luxury few can afford, and is actually pretty far down the list of what is required to be an artist. Drive, for instance, is a hundred times more important than talent. The urge to get up at three in the morning and start cutting your movie. The need, the absolute uncategorical necessity to motor for three days across the country, nearly sleepless, in order to make it to a certain deserted beach where the light will be perfect. And not simply this one day, but every day after day. This is how artists are made, from the inside out, via a practice that is daily, every step after step, and John was busy taking these steps, no doubt about that. Running the film through his fingers, his basement chemistry, his chance encounters. This is how the story goes: the artist is dedicated, and resolute, and usually it is not enough. There are modest successes OK, but the magic, the shine, still manages to elude. Or it lights up a small corner of his house, it might extend to his neighbourhood perhaps, where the other seekers, the other like-minded devotees, might come to witness. And then that passes away too.

After the initial burn, most artists give in, give way, give up. There’s no more, there’s nothing left to say, real life decisions about how to make a living need to be made. As the artist gets older, the walk becomes a little steeper. It’s harder to stay up all night when the joints hurt, when the results aren’t coming quickly enough, when you’ve already been there through the night after night. The happy and inspired moments don’t look quite as fine whenever you show them to anyone else, in the presentation instant those monuments to cinema shrink back down into something that looks plain and ordinary. And then you start to wonder: am I just an ordinary person, living an ordinary life? An ordinary artist, making ordinary art?

Kid Stuff

Let’s go back to the story, the way it always goes. The home truth. The gospel. The artist does the best they can, and sometimes that’s good enough, and sometimes it’s not. And then they get older, and make the unthinkable decision to find a life partner. The old story goes that if they get married to someone who does all the work, OK fine, no problem, no worries, the struggle of making can go on pretty much as before. But if they start having children, and actually pay attention to them, I mean, noticing that these small humanoids are separate from the artist, perhaps even taking a hand in their raising, even throwing themselves into the new life that surrounds them, then that’s it, sorry, you might as well hand in your smock and beret and paint brush, because it’s over. No real artist could survive that.

That’s how the story goes. But with John it didn’t work that way. He and Lea found each other, and two years later they had Charlie, and after Charlie came Estelle. And it’s true, it has to be said, the magic didn’t happen right away. He was so stunned and excited and astonished about Charlie that he couldn’t stop shooting him, and then rewinding the camera and shooting more of him, until he had made ten thousand dreams (6 minutes 35mm 2004), a footnote of a home movie, and then there was The Almanac (52 minutes 35mm 2005), shot with a small, hand-cranked 35mm motion picture camera, offering observational vignettes which didn’t quite become more than the sum of its handsome parts.

Making Pictures

But after that he found himself at the crux and crossroads, all of a sudden he was making the movies he was supposed to make all along. It’s true, the initial burn was gone, drawn out in a raft of emulsion experiments and happenstance. But now there was a renewed purpose to his shooting. For me it begins with Making Pictures (13 minutes, 35mm b/w 2005).

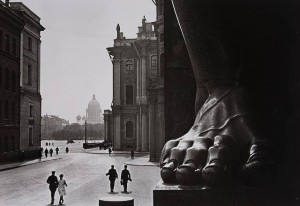

“I shot some super-8 in China that I blew up to 35mm and hand-processed which looks almost like things are happening in a blizzard… gigantic grain that documents Edward Burtynsky shooting with his grainless 4×5 camera… and Peter Mettler shooting super-16mm off a tripod. Despite the fact that there is no sound, I sense that the film will end up as a critique of the documenting process. My camera managed to see both things going on at the same time: people working with cameras and people working with concrete and steel. It makes the observers seem completely out of place in the landscape (which they are). I created shots on the optical printer, fading in from white into a still frame of Ed, or a peasant, or a landscape, and then it comes to life for a bit, and then usually ends on a freeze frame of a child, or a couple of children, or a group of children… and then it fades to white. It was an amazing process that way, no video transfer, just the super-8 that I processed as a negative in the projector and a bit of guesswork. Not a lot of editing was required, more like sequencing.”

Could it be his best movie? Not that there has to be a best, here in the fringe we have done away with tops and bottoms, except when it gives us pleasure (when we want to try that on too). In order to pay for the habits of his living (a roof for instance, his old car fetish) he works as a camera assistant on mostly sub-optimal movies, large budget spectaculars requiring dozens to produce the place where an image could be, if there was one. But occasionally there are gigs of another kind, like Jennifer Baichwell’s documentary on Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky. Shot largely in China, at the site of ruinous dam projects which have tragically displaced hundreds of thousands across the country, Baichwell follows Burtynsky as he maps out his coolly framed, large format panoramas. The people in them are small and crushed and part of some larger (globalized) project of power (electricity for the new century).

Behind the photographer Peter Mettler works his own camera charms for Jennifer’s documentary. And between these poles of representation, between image and tragedy, daily life and work, is the super-8 camera of John Price, flinging his body into other bodies, meeting their look, walking their streets, searching for a place to begin the work of greeting. These are pictures made between other pictures, between frames, in the off time, the margins, when the real work has been done. He rushes into these off-camera spaces with deliberation and an empty mindfulness, guided by voices, because the work of looking has not yet ended. Back home, he looks at these raw camera rolls through another camera, finding a structure for these live moments through a camera’s camera, an optical printer, where he makes a blow-up (“live”), freezing frames and sending them into white oblivions before allowing the next encounter to appear in all its daily opacity and wonder. His looking is an invitation and a refusal. Can you follow? Yes, absolutely. Can you see what I see? No, it is too singular, too wrapped up in the life of John’s body, and the strangeness of the bodies which he meets, which he meets without meeting. But nonetheless, between these blank punctuations there are moments which open the heart. More than we dared hope for.

Pictures in Conversation

Perhaps he is most at home as a miniaturist. Never mind the symphony, the orchestra, I’ll just sit here at the piano bench and lay it down one note at a time. I don’t need the curtains, the baton, the big swelling sections all heaving together, it’s just as good to dedicate oneself to this small moment. In John’s work, this impulse often takes the shape of a single roll – shot between madcap beer adventures at his kid’s birthday parties, or up at a friend’s cottage, or at the side of a road. They are moments caught in passing, and then run through his chemistry maneuvers. But he always wanted more, even at the beginning. He had rolls of silver happiness filling the drawers, but weren’t they all really part of the same film that he had been making all his life? Couldn’t they be coaxed together to produce a larger statement, a more sustained reflection? Oh God, how he tried. He got into the habit of spending long months in the editing room, sweating the relations between instant of shooting which had been gathered on the fly, trying to push and pull them into some kind of larger shape, trying to find some subterranean current that ran underneath all that looking. Running the pictures over and over. After Eden (30 minutes 2000) was both a summary work and a portrait of his Vancouver life, with one eye fixed on a rear view mirror that kept changing focus. And then there was his travelogue Passages (24 minutes 2003) that probably cost him a couple of summers, huddled together with his pictures in dark rooms, trying to develop a conversation between a few rolls he shot while wandering through the remains of empires abroad. These retrospective stitchings were never quite as perfect as each individual stand. He was making beautiful pictures, but they weren’t flowing together. It’s as if he had beautiful words which didn’t want to collect into sentences. Now what?

Rescue

His children came to the rescue. All of a sudden there was no more time to be spent on the editing machine, rolling the same images over picture heads in every possible configuration. Instead, there were diapers to be emptied and urgent wordless needs that needed deciphering over a hundred sleepless nights. If he was going to keep making movies, he was going to have to find the in-between moments, in other words, like so many artists before him, John’s process had to change. This crisis was also (like every crisis) his opportunity, the way out of his own blind spots. What he was supposed to do was build a wall and stay on the other side, or get angry, or simply drop the whole situation like a thousand thousand other neglectful fathers, never mind artists. But instead he opened both arms and swan dived into fatherhood, reveling in every moment, feeling his feelings and theirs, content to let the movies take a second place, knowing that some bit of his footing, his core, was bound up in that making, that he needed to make a little window of time for it so he would feel alright. But that was ok, he had a new subject now, the miracle of his boy. He had never thought he could love anyone as much, for as long, or accept so much, and then his girl Estelle came, and it all happened again.

Children not art vampires

He was supposed to become a sleep-deprived, baby-talking, ass wiper who would cry while reading Christmas cards. But I think it’s only after the birth of his kids that John has really come into his own as a filmmaker. He continues to be drawn to moments of a landscape, or a child’s face, or an afternoon spent in the company of his friend’s children. But these brief observational bits are now made with a profound assurance, even an easiness, that some of the earlier work strived for. Even his throwaway moments are golden, like Party 4 (2:45 minutes, 35mm, 2006) which shows Charlie’s second birthday party, smeared in chocolate cake and ice cream, all shot in the kitchen with a doubly exposed wind-up camera which takes these tiny joyfuls and blows them up outrageously. Or gun/play (9 minutes 35 mm, 2006), a three-parter which finds him running around with a young boy and his trusty weapon, and then alongside his own father in a grainy bird watch, and finally looking on as a boy makes disturbing and enigmatic gestures at a beach. Or Naissance (10 minutes 35mm 2007) which narrates (in silence) the birth of Estelle, the afterbirth luminescent in John’s hands as he buries it in the backyard garden, Lea’s nipple glowing like some lighthouse beacon for this new life.

He followed up with his reigning masterpiece (so far), View of the Falls from the Canadian Side (7 minutes, 35mm, 2006). Shot with a small, hand-cranked, 35mm camera, Price visits a tourist’s playground and returns with the mystery intact. Instead of using his camera as a shield, to protect himself from seeing, here he strips away the layers of culture and artifice and returns us, in a sublime chemical reworking, to a primal scene of witness. Those vast supernal bodies of light: they’re us! He shoots both the tourists and Niagara Falls, and lets us wonder at both parties, marvelous and mysterious.

“A film commissioned by LIFT (Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto–a film production co-op) for its Film is Dead-Long Live Film omnibus project. In 1896, William Heise photographed the first 35mm motion picture images of Canada at Niagara Falls. The 4 perforation camera system he used was designed and built by Thomas Edison and William K. Dickson. The stock was manufactured by George Eastman to Edison’s specifications. This film was photographed using essentially the same technology and is dedicated to the visionary ideas of those pioneers.” (John Price)

The opening gesture is in colour, in a wide screen extravagance that turns watchers into watched. The tourists have gathered round the world to gape, and owing to John’s chemical magics they appear reconfigured, touched, and transformed. They have come with their large bellies and small digital cameras to try to keep a distance, to try to keep the miracle from happening. But what is astonishing about the Falls, viewed and reviewed on postcards and T-shirts and Marilyn Monroe movies, is that the encounter itself strips all of that away. Some old wonder continues, and by running the footage through his chemical soaked hands, John adds a devastating light that comes up out of the watery cascade.

When the tourists are released, after a single camera roll, the Falls appear in black and white in single rolls arriving out of a soft focused haze, and then dissolving back into it (which permits the processing marks, in watery baths of a different kind, to be seen more clearly.) How to see what has been seen too often, how to make visible what becomes invisible not via repression, but through overexposure? The steady pulse of these pictures, turning in and out of the focal plane, allows the Falls to become visible, exactly because they are so fragile and momentary; this small window of focus is already slipping away even as it appears. I accompanied John on one of these excursions, and it was a mid-afternoon delight to see him set up his small wooden box of a camera, entirely blind (there is no way to see “through” the camera”, rather, it is pointed towards the subject in wide-angled hope), steadily cranking the film through the device after looking and looking again. I think he exposed two rolls that day, a couple of minutes at most, which were taken home and processed in his basement. That was the beginning of his camera visitations, the movie took shape as a result of the evidence, the encounter, the act of seeing with his own eyes. Editing meant cutting these rolls together, end to end, in between playing with his son Charlie and his daughter Estelle. The wonder of their appearance arrives in the basement chemistry because he is busy all day letting them teach him how to see, how to turn the neighbourhood into small wonders just like this. A crack in the concrete. A patch of grass folded back, leaving the impression of a head. The cataract of water. In the final roll of the film the spectators leave, rendered in high contrast black and white, their bodies glowing with the charge of all they’ve seen. Then it’s time to go home and live those miracles.

The Present

He doesn’t have to drive across the country anymore to stop the storyteller any longer, his kids look after that for him. He was never a planner, a conceptualist, he was never married to the big idea. What he has found, in his playtime and child rearing, and an admission that experience needn’t be curtailed by the Frontal Lobe Surveillance Society day and night.

What makes John so special as a person, and as an artist, is that he is really here. Right here in front of you, right there on phone, right here behind his camera. He’s not wishing he was somewhere else, or complaining about how it is, instead, he has learned the most difficult art of all, which is to embrace and accept what is actually going on. When I speak with John, which is not nearly often enough these days, I feel him pulling me here alongside him. Come here. Come now. He urges me in the softest way possible. In this, as in all the important matters in his life, he takes the lead from his children, who are his first and best teacher. Let them take us out of the prison house of adulthood. Watching John run alongside his kids I understand at last: we only live twice.