Hey Matthias

Stefanie called me tonight, a buzz I heard in sub-audible mode from the phone upstairs, the only one temporarily functioning, not even a ring but its suggestion, followed by that long ago voice with a request for a few thoughts about you. The deadlines are long gone of course, we are past the end, already an afterward the two of us. I think we will always have a home here.

Stefanie explains that the words don’t need to arrive in suit and tie, no footnotes to friendship please, but something more casual. I suggested a found text of course, an old mail for example, but after reading through our correspondence of the past few years I realized I couldn’t offer up that either. They are filled with a merciless self examination which I take to be particularly German, though in your hands it is only beauty. How is it that everything you touch is still turning into cake? Your writing is forever witty as if already publication bound, ready for its close-up. Best to leave it sleep until the next generation of Panthers banishes it all as unreadable code. These stories (which are not stories at all), which remain the root of every picture shown at festivals large and small, can’t be told here. Likely no where else in this volume, I’m afraid. For how long now have I, have we, been trying to rid myself of the secrets waiting in my mouth, but need to keep these too, for both of us.

And besides David isn’t well. I got the news in Amsterdam, and it promptly sent me into orbit. What am I doing here? Tourist in my own life, sharing sound bytes with strangers, sampling possible lives in dreamt-of cities and now this cruel judgment. Oscar wrote that friends stab you in the front and Tanya added, when her best friend shrank away into cancer (he looked so tired and then he didn’t get up anymore), that she didn’t want to be the next to go, but that she didn’t want to be the last either, the one left behind to tell the stories.

We lit down to David’s screening Saturday night in Buffalo wondering if he was going to say anything about it, how could he not, we’ve all come from so very far away after all. But how could he, there were strangers in our midst, innocents in the theatre who might not smile back into these rigorous, SILENT black and whites. In his introduction (was it?) David only says, “I’ve been under the weather.” His cancer is eating him even as he’s standing up there in the light of his movies, lending words to the silence that will follow him, that will fall before him, much as we are doing now, rubbing our words together, our company together, before it’s time to say good-bye.

Matthias, each of your movies flings you back into the world, far from the small town universe you call home. The early ones with their small gauge injuries, and the later ones too, though it’s harder to figure there, in the jovial company of Christoph’s stern rigour. This necessary force field of conceptualisms and found footages and collaboration has been enough to keep clamouring attentions from the private wounds which you manage somehow, against all expectations, to keep smuggling into your movies. I can feel the effort this involves, the terrible restraint which threatens to shatter the beauty (above all, let it be beautiful) which you present in all its fulsome terror. What I never manage to understand is how you get your personal traffic jams to look like Cary Grant or Lana Turner, well, especially Lana Turner, whose face never fully belonged to the one who wore it. Is that why her sadness still hurts? The mystery of this face, of how someone else’s face can carry your hope in it, and the way it looks when that’s gone too. These stories have been lived before they’ve been lifted from the dream factory, and settled with loving care into a movie which could only be yours, even as it already belongs to everyone who sees them.

I spoke with another David tonight, the one who brokered the news while I looked away, couldn’t bear to hear it even as he was telling me long distance. I turned my camera on instead and pointed it up towards the window where the light was crying through the leaves. Not now, please don’t let it happen right now to me or to anyone else I know. Take all of the others, men, women, down to the last true believer. Just spare me the neighborhood, the few blocks I call the world, just let tomorrow look the same as today. Later, when I got back home, I replayed the footage and felt I was watching him leaving this world behind, but I’ve been wrong before. The next day we went to Ottawa for fun, as if there was any time left for that now, and I couldn’t say a word to John, needed to be alone with this new grief until the day after that when he made it better for both of us as we slipped into a more comfortable way to say good-bye.

The responsibility of witness. I was there. I saw. And now I am responsible for what I saw. As if it was my cane, my weight loss and screening. Should I go down to see him in what may be his last weeks? And why all this time apart between you and I, Matthias, the long sojourns between festivals and openings, the lag between mails while we are fading (are we fading?). Why are we always… (the German word is immer which seems just right now. Immer, it’s a damnable sound of protest, hopeless protest of the zimmer, the forever room we find ourselves in, the walls we have spent our whole lives constructing.)

I remember the first time I didn’t see you, in Arnhem, where you left greeting cards behind which showed a handmade torch holding a flame, and beneath it the authorless anti-slogan: Alte Kinder (Old Children). I couldn’t figure at the time how young, how old. I returned a year later to stay in Bielefeld, a city you four Alte Kinders (flamethrowers) assured me was the centre of the German fringe (When I inquired about Berlin, a city I’d only seen in newsreels, each of you sniffed in turn. “Schnee von gestern.”). I didn’t realize that the jump charge of excitement I felt was the frisson one gets at the end of something, instead of its beginning. Within months the four of you would go your separate ways, though not before the Heins split (they were always first with everything), and then Schmelz dahin, and then the wall came down. All the fledgling hopes held high by the squatter’s boom of the 80s, all those meters of narrow gauge expectations, seemed to belong to a country of mind that didn’t exist anymore. Except in your Bielefeld flat (did it really take eight years before you decided to move upstairs?).

You said you would make me a very special dinner (the phrase “very special” means something different in Germany than it does in Canada where everything is already super maxed beyond endurable limits, in Germany a single phrase stands duty watch for superlatives). I tried to suppress my disappointment as you came home with a bag of asparagus. I have always had an uneasy relation to vegetables, I understand they’re necessary, but they hardly constitute dinner, they are only its accompaniment, like the others waiting in line to get into the concert. Of course they’re necessary, you just try not to notice them once you get in. All afternoon you peeled, slowly and carefully, every stalk granted its last hoped for attention. I was hypnotized, and when they were finally served hours later I ate them with a rare happiness and vowed never to eat white asparagus again so the memory might be preserved. One of the few promises I’ve managed to keep.

I said I wasn’t going to reach back and found footage our mails but I lied. It’s a bad habit I know, saying one thing and doing another. But this was too irresistibly perfect, in fact, with your permission, I’d like to use it for a book I’m going to write, that I keep putting off writing. It will be a novel, set in a city we both might have lived in once.

I can’t remember who you were talking about when you wrote this, but I can guess. I think we can both guess. You put it like this: “We are having a rather calm and relaxed correspondence while the real passions are passed over as being too dangerous. Oh yes. Is that why we all get sentimental at an older age, frustrated, cynical, accusing ourselves or others, is that why we feel trapped by our own decisions, and why we expect MORE HAPPINESS AND FULFILLMENT all the time? But: real passions have to go through changes, too. Are they still real after a dozen years of living together? Or are they just routines, beaten emotional paths, strategies of taking and giving, of avoiding controversies and accepting the unavoidable? I don’t know.”

Next week I will go to see David, and try to say a few words, and listen, most of all that, it’s what I can offer him now, which isn’t much. I will bring my camera in order to cheat death a little. When I get back I’ll tell you about it in a letter which will also try to cheat death a little bit. Hope I’ll see you soon, in circumstances which are only sweetness (because you deserve them).

Mike

It’s Perfect!

The expression on Matthias’s face is a mixture of mock horror and concern. Both hands flutter north to cover his mouth, the brown eyes widening. “I can’t believe it.” It is a gesture, learned and relearned, but each time he invents it anew. He does it again, for the first time.

I’ve just told him that I’ve only been on the beach twice in my life.

Matthias has learned the cost of being a mother (the mark is everywhere in his work), so before taking me to the beach he insists we buy an oversized umbrella in a shop filled with Jesus replicas. Like the avant garde in art, every religion has its kitsch. He walks us past the assembly line Christs (the word is made flesh, and then plaster), flaunts superstition by opening the umbrella in the shop and says it will have to do. We’re on our way.

The Jesus image (the body flayed and nailed, in the hours before death, in John’s words “and he in us”) reminds us that the healthy tans of one generation are cancer in the next. But when we get there we find Christoph already sprawled across a choice bit of cool sand, determined to overlay his northern European pallour with a baste of Portugese high noon. Like Matthias, Christoph is a graduate of the Braunschweig Art Academy, schooled in the take-no-prisoner critiques of Birgit Hein, herself one half of the primal couple of the German fringe. Five years back, Matthias got a call from the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford to produce a little something for a Hitchcock exhibition. Matthias promptly rang up Christoph and together they set off on a picture journey that has already produced half a dozen picture perfects which have raised the stakes of the found footage genre. The clarity and precision of their movies is nearly unbearable, founded on acts of rigorous collection and rhyming gestures. A duet of exacting attention and beauty.

Like the classic artists of centuries past, they are concerned first of all with making a portrait. What does it look like? What does this face tell us, which has already glimpsed its own end, and returned? But they are not engaged in life drawing, or plein air pursuits, instead they render a picture of the pictures which surround us. They allow us to see these Hollywood excerpts, and the Euro faces which have haunted the imaginary of a continent, which have been reproduced in a line that has made a vanishing point of our faces. They bring these phantoms to life so that we can see them again, for the first time.

The furniture is a picture. These hands are pictures of hands. This look reminds me that my look is also a picture, I bought it for eight dollars in an all night flick marathon, and watched the heroine crumble when every hope she ever had walked out the door. I didn’t watch her, I swallowed that look, it’s my look now, my face. These pictures have become my face.

Imagine the wedding bells: Matthias the lyric nitrate poet and Christoph the digital surgeon. I knew Christoph from his King Kong excerpt Release, Fay Wray roped up and c-c-c-c-convulsing, the body heaving in a virtuoso machine display he enacted via hundreds of micro-looped samples drawn from just four shots. (Who says there will be no pleasure in the new order, though at what cost?) What would this uber VJ bring to Matthias’s childhood reveries, his pair of AIDS laments (one a psychodrama of doubled bodies shot in Portugal, the other a hand-processed diary opus grieving a lost friend), his dreamy sailor erotics (shot through, like all good sex, with terror), who had found in Brasilia an image of an exhausted utopia every inch his own, emptying his tank out into one last masterpiece before slumping exhausted across the festival carpet to receive his just rewards. Most artists continue to fill frames long after their moment has passed, but habit impels them to generate new pictures, shadows of giants, which only appear large, in the right light, looked at kindly by friends. Matthias finds a way past all that, he cheats in other words, it should be over for him, he’s been up on the wire for too long already, drinking from the deep place these high fine pictures come from. Now it’s time for him to come down or develop unhealthy pharmaceutical dependencies. But he’s clever, this small-town cosmopolitan, and through hard work he manages to generate, in semi-regular intervals, bouts of good fortune. A chance phone call arrives from Oxford with an offer for a bigger stage and some money to buy time. Another call follows quickly to Christoph and the engagement is on. They set to work carving up Hitchcock’s fourty films into six densely packed chapters. Somehow, in just 45 minutes, they manage to leave nothing behind.

Now that the spectacles of years past have been shrunk to fit home screens, cinema’s déjà vu is increasingly available for personal review. After the corpse, the morticians arrive to reassemble the body. Matthias and Christoph delight in their work, who could trust a surgeon that doesn’t like to cut? That doesn’t feel each incision into the body as if it were his own, and smile? They are grave diggers, necrophiliacs and lovers. The way they touch these pictures makes me feel (and I revel in it) like a voyeur. Sometimes bluntly with the back of the hand, sometimes so lightly that only the slightest alteration of the picture plane occurs as it passes through them. This is how they caress her sleeping face, a lost ticket, an oncoming train.

When the artist is finished, I get to stand in their place, trying not to feel that I’ve come too late. They arrange the view, or rather: they put me in my place. They place me. In Play, the dynamic duo gather pictures of audiences, reaction shots to a scene which never materializes, except in the theatre or the art gallery, where it is clear these faces are looking back at us. We are granted an image of ourselves. How do we look?

And he in us.

Play (so named because all the audiences we see are attending one) attaches itself to the mystery of the third person, the crowd. Not I like but we like. Not I see but we see. The cinema, at least on one side of the screen, always shows a crowd scene. Both makers are German. Have I mentioned that already? Have I ever stopped mentioning it? Their grandparents’ generation was part of the Reich, it’s that close, close enough to touch almost, and the Reich’s mass hysteria verges behind every Cary Grant close-up here. What is the relation of the many and the one (Godard; “The state dreams of one, the individual of two”)? The urgency behind this question is particularly German, which renders the cutting here precise without being tidy. We see a crowd in wait, gripped with dis-ease, what they need is that one of their number tear themselves away from the undifferentiated mass, that someone declare themselves, perform themselves, and so allow the crowd to unify in cheer (or derision), to allow the crowd to become itself, the individual must be asserted. What is commonly held in contradiction (the individual versus the crowd) turns out to be two sides of the same coin, part of the same play. The crowd makes the individual (the star) necessary. In the language of cinema: first the long shot, then the close-up. What is left in the end but to applaud the crowd which makes the individual possible? First: we are. And only then: I am.

What else are they showing in sunny Vila? Well there’s Album by Mathias, a 24 minute diary travelogue, dvcam moments with small onscreen texts attached (“others rehearse the events that have yet to happen”). The images are beautiful, call it a curse or affliction but this boy can’t help it, the world runs through his camera and it shimmers in review. He is drawn to these moments of light, a night lamp winking, a silhouette cutting up magazine photos for his diary, a jet plume become the horizon line of a nearly still ocean with a bird slow flapping across the distance (Am I the bird or the water?). There is a crimson light and then a bag which attaches itself to it (is this love in the object world?) Newspapers reading FEAR blow open and close (the image is also a sign, a warning). And everywhere there is mist and overhanging clouds and factory fumes, the world is disappearing without leaving a touch. The filmmaker appears as a shadow at a rail, finally joined by another shadow (as if he is not chronicling his life, but its disappearance. When his shadow is met I think: we are disappearing together.) Everything is lonely here, and from this loneliness emerges a terrible beauty, the two are inextricable, no way to speak about one without the other. I wonder how he manages to look at a wall with such tenderness, to open himself to a curtain, the sensitivity with which he draws these landscapes. At what cost?

The road is sunny and bright and the four of us push along easily. I never see them apart here, putting their hearts into leisure with the same dedication that they bring to their computer homes. We pass the abandoned arcades of Vila do Conde, a town both old and new, host to the world’s big easy film festival, where the movies don’t begin until the afternoon, giving us some serious beach time. We’ve had our perfect breakfast, our good morning America blow job, now it’s time for the beach.

Christoph Girardet. I’d heard about him before of course, even spent a few huddled moments at some German festival swallowing beer and cigarettes before racing back to catch more of the new as it hurried its way into the past. But this was the first time we could sit for a reliable chat. Like anyone whose heart is broken, who is deeply and profoundly sad, he clowns all the time. He is a speedbag of punchlines. And curiously, just like Matthias, he looks like he has just stepped out of an American movie made in the 1950s. Neither would play the lead, but somewhere in the posse of hard boiled (and soft hearted) detectives they might be found, breaking the law in order to keep it.

I shrink underneath the umbrella, trying not to let an errant ray strike, riding Christoph’s laugh until he pauses for pronouncement on Matthias’s work BC (before Christoph), that celebrated string of fringe hits. He turns to me with all doubt left behind, the words of the oracle are waiting, “Matthias’s earlier movies had mistakes in them, you know.” Matthias, listening off his shoulder, nods in agreement. Yes, the tribunal has decided, there were “mistakes” made. Only a German could say something like this. The merciless scrutiny of their own work (their own emotional lives, their own small fragile hopes) allows them to dream of a past with “mistakes” which can be identified, and no doubt corrected. Of course the secret dream each of them holds, unable even to confess it to one another, is to produce that most German of all art manufactures: the perfect art piece. I love it, it’s perfect! Their genius (or good luck, it’s the same in the end) is that their happy sadness erases each other’s blind spots, while at the same time they save each other from the dream of perfection. The next year I come back to the beach at Vila alone, looking for a trace of where we stood and talked but there’s nothing, no matter how long I look. This relieves me more than it should.

(Originally published in Vila do Conde Catalogue, 2005)

South to Hitchcockville

What does a big league, famously cruel Hollywood suspense maestro have in common with a handsome from small town Deutschland, a filmmaker okay, but one whose pursuits of the fringe have been so resolute, no marquis for this nightlifer. We’re talking Alfred Hitchcock, an American whose popular appeal was granted critical heft by the Nouvelle Vague in the 50s and femme psychoanalysts two decades later. In the nineties, his blood rich melodramas have proved an irresistible source of plunder. He is the Titanic of the art world, a one man archive whose work is as accessible as the nearest video store. Stealing has never been easier or more fun. Art wunder star Douglas Gordon grabbed his bit of the brass ring by simply slowing down the maestro’s best known montage opus, calling it 24 Hour Psycho. Pierre Huyge’s shot-by-shot remake of Rear Window (using unprepared non-actors) in Remake gilded his monkey. Les LeVeque gives us a mirrored, attention deficit version in 2 Spellbound. The list goes on.

And now another has weighed in. If Matthias Müller is considered, at this moment, possibly, fringe media’s MVP, his reputation rests not so much on the signature gesture, the cruelly repetitive trademark a guarantor of some sanctity of soul. Instead, each new outing shows us another face—after his super-8 diary opus about AIDS (Aus Der Ferne/The Memo Book 1989), he turned to the blue-toned sailor boy dreams of Sleepy Haven (1992), then made a drama (Alpsee, 1994), switched again to a found footage brief (Home Stories, 1996), a hypnotic psychodrama in Spain (Pensao Globo, 1996), a study of architecture and alienation in Brasilia (Vacancy, 1997). Each had proved a triumph, copping awards in all the fests that mattered, tour following tour, his exacting montage a public wonder.

And then the call came. It was from the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford, who wanted to host a séance for Hitchcock. It had been a century since he was rocked into the cradle. Time flies when you’re having fear. Cindy Sherman, Atom Egoyan, Douglas Gordon—they’d lined up the art stars all right. Was he interested in breaking the bubbly with the blue chip crowd? There’d be cash too, enough English pounds to keep the landlord off his back for a few months, hire an AVID if necessary, rent a few tapes. He was in.

Faithful to his charge, Müller went on a steady diet of puff pastries and chocolate creams, shaved his waning pate, added a brogue to his already impeccable anglais, and swapped his polyester for suits. In a matter of weeks, after a brief visit with his plastic surgeon (you mean you want to ADD fat??) he had become the spitting image. Indistinguishable. Knowing he couldn’t face the dead world alone he enlisted a friend, Christoph Girardet, whose quick fingers had turned Fay Wray’s boyfriend gasp (what if your lover weighed in at 2000 pounds and stood ten stories tall, not to mention all that hair) into a paroxysm of sexual heat and fear. Together they would make their way into Hitchcockville, determined to dissect the master’s corpse, and make him again in their own image.

Courtney Love said of once beau Kurt Cobain, junkie king of grunge guitar, that he chewed bubble gum in his soul. That no matter how much feedback juice he laid into the machine, no matter how much pain he shrieked into the microphone, it all came out as tunes fourteen year olds could hum along to. Müller shares this quality. No matter how disparate the material, no matter how underground his pursuits, he turns everything into stories. With a beginning, middle and end. Though not necessarily in that order.

Phoenix Tapes by Christoph Girardet and Matthias Müller

45 minutes Betacam 1999

1. Rutland

2. Burden of Proof

3. Derailed

4. Why Don’t You Love Me?

5. Bedroom

6. Necrologue

Phoenix is where Marian Crane, Psycho‘s road weary starlet, heads south for freedom, though each mile brings her closer to death. Phoenix is the mythical bird which rises from the ashes in resurrection, just as these films are re-animated from Hitchcock’s work. This collection surfs the uncanny webs of Hitchcock, finding the master of suspense prey to Oedipal traumas, overbearing mothers and femme fatales.

1. Rutland

Rutland is a geographical portrait, a collection of settings and establishing shots. Filled with entrances and exits, it is a narrative of waiting, punctuated with black-outs, as if the scenes themselves were losing sense of their narrative function. Forgetting. While mazes are usually constructed to enclose its inhabitants, here is a labyrinth of exteriors, emptied vistas waiting for action, sites for deceit and discovery.

2. Burden of Proof

Close-ups rule the roost in this elegant collage of moments collected across the Hitchcock canon to form a kind of meta-narrative. Collages of ID cards, packing clothes and parcels, give way to keys withheld and hidden. As keys are dropped, a drain issues fluid, and then a series of bloodied hands follow, people trying to wash off blood. Notes are written, texts of various kinds appear: racing forms, telephone books, and then a telephone montage, telegrams, closed doors, hands trying to open doors, coffee cups, jewelry thefts, hands on the wheel of a car. Each fetishized moment leads inexorably towards another, as these bits of isolated attention move together in a delirious vortex of deception.

3. Derailed

This miniature drama is set in a train, its looped sleeper made to dream the nightmare of journeys past. Faces leer out at him, women feint, a crescendo of crowds build and fade until at the last hands reach to thwart a terrible fall. Always too late.

4. Why Don’t You Love Me?

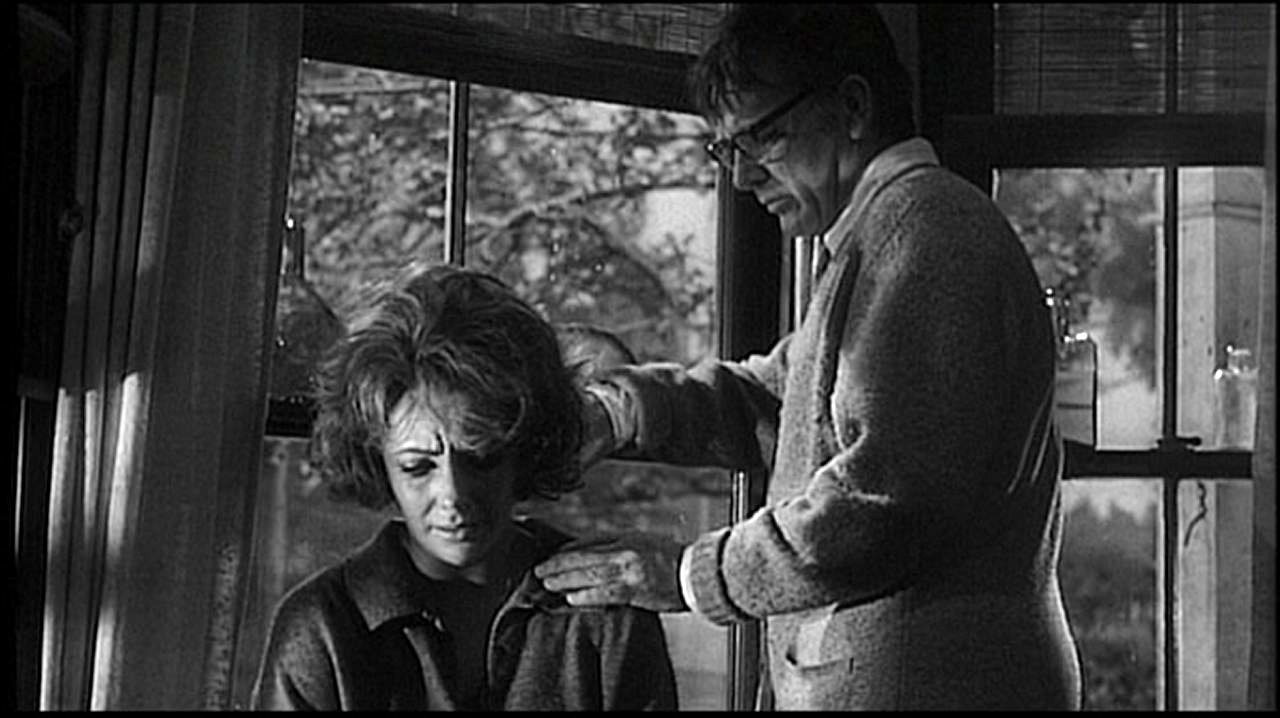

The wickedest film in the Müller canon, this take on maternity is blunt, unsparing and deliciously funny. A man waits bedside hoping to rouse his sleeping mother, intoning over and over: “Mother. Mother. Mother.” Once awake she appears clearly in control, as the collage of traumatized, guilt ridden men make clear. Disdaining the romantic choices of their sons, crafty and manipulative, she forbids any kind of sexual expression, while at the same time developing illnesses which ensure that the son will never stray far. The result, as Müller/Girardet take pains to point out, is misogyny and matricide.

5. Bedroom

Welcome to heterosexuality, Hitchcock style. Begun with a collage of women waiting alone, the mix of dread and anticipation is already palpable here in their anxious turns toward empty doors and windows. Sleepless nights and preening before the mirror finally give way to moments of presentation, where they appear before their beloveds who cringe away in fear. Stricken and traumatized, they kiss, though she looks away, already filled with the knowledge of the dark thing which lies within him. The mood darkens a last time as these impotent warriors vent their aggressions in a montage of brutality and rape, bondage and death. Murder is not seen here as the other side of love, but a part of it. Inevitable.

6. Necrologue

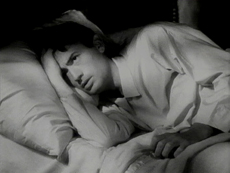

Necrologue is aptly named, combining as it does two words: necropolis: the city of the dead, and epilogue: the conclusion. It is comprised of a single shot of a woman waking from sleep (Ingrid Bergman in a sliver from Under Capricorn). Slow dissolves show the faint tremor of her eyelids, which widen in hope, then dread, before falling closed again. Not: “Oh, it was just a dream.” But: “Oh, it was just a nightmare.” In other words, real life.

These half dozen video pictures dream our collective past for us. All those nights spent in the dark, training our attentions, looking at Hitchcock, learning what it means to fall in love, to die, to live for an obsession. Not just the pictures we dress our lives in, but the pictures our lives have become.

Scattering Stars: The Films of Matthias Müller

When I ventured into Germany in the fall of 1989, scant months before the wall came down, one of the most enduring surprises was the widespread and elegant use of super-8. While I’d cut my teeth on difficult filmmaking at the Funnel, haven for narrow gauge makers, it was usually associated with a rough hewn aesthetic, and an approach to filmmaking that was not so much guerrilla as kamikaze. What I encountered in Germany was of another order entirely, and while it’s difficult to generalize about a production that was so prodigiously decentered in its proliferation, there was an exquisite care and a meticulous unfolding of possibilities I never dreamed imaginable. Conditions have changed in Germany over the intervening years, integration with the east has meant declining government cultural subsidies, and the collaborative efforts that dotted the German landscape, eschewing traditional notions of artisinal authorship, have since collapsed. Many makers have turned to video or day jobs, and cultural priorities have shifted stateside into the promotion of ‘new media’ — CD Roms, computer interface, das internet. But a handful of makers endure, and none more elegantly than Matthias Müller, who was, at the time of our meeting, simply the best super-8 filmmaker I’d ever seen. His jewel-like apparitions continue to astonish, even as he re-invents himself using a broad iconography of 50s melodramas, diary documents and an expressionistic lean learned from the pre-Weimar period.

Born in 1961, Müller attended his hometown university of Bielefeld in order to study art, and it was there that he would meet Christiane Heuwinkel and Maija-Lene Rettig, two young and fledgling art students who would soon turn their attentions to cinema. Together they would form Alte Kinder (literally ‘old children’), a self-styled distribution organ that would tirelessly arrange tours, catalogues and speaking engagements. The small, provincial nature of their hometown, and the eccentricity of their practice, made touring a practical necessity, both to encounter like-minded makers, and to share the yields of their discoveries. They invariably accompanied their work, hoping to soothe with the balm of rhetoric what their narrow gauge aspirations might not make immediately clear.

After a series of one cartridge quickies, often made in collaboration with others in the collective, Müller completed Continental Breakfast (19 minutes 1985). Originally photographed in super-8, it was re-photographed (again on super-8) from a television screen, retarding movement and lending to the whole a blue haze. Fuelled by a pulsing video raster, and scored with a somber violin tone and approaching footsteps, the camera begins a slow aerial flight over its sleeping subjects, a couple in morning bed. A montage of freeze frames undrapes their slumber, the woman finally starting awake and slipping away from the primal scene. She enters a shower re-photographed again in freeze frame mode, the water here transformed into a solid mass or curtain as the male sleeper turns. She appears to wipe away the memories of sleep, to push away the anxious memories of her recline, even as his small movements – pulling up the covers, turning into the bed, emphasize his quest for escape. She weighs herself, dons her morning robe, checks the fridge and lights a cigarette while her partner continues to sleep, the video raster lending a white pulse and throb to his flesh. Shifting to colour, with the same image staggered in time and printed on top of itself, she sits down, her phantom appearing to settle inside as she prepares herself for the day’s first meal. He appears alongside, and they breakfast together, shot in pixillated briefs, their domestic gestures repeated in a rhythmic incantation of their life together. Alternating between colour and black and white, and separated by brief passages of black leader, a radio voice begins speaking about the dropping of the first atomic bomb as he takes up the paper. The first of many headlines appear: Bitter Enemies, Stay Away, superimposed upon itself to form a cross, and then a view of earth from a looming spaceship. “Tragic youth with no hope” another headline screams, as the track fills with sounds of war, with the newspaper headlines increasingly supered over the couple’s breakfast. Fragments of opera, radio chatter and synth gurgle propels a montage of isolated moments: faces glimpsed in silhouette, TV snow, and extreme close-ups of eyes opening. “We have come too far for there to be any turning back now” introduces a montage of World War I soldiers charging towards the wire, dying horribly before the camera’s impassive stare. “Talk is pointless” is supered over aerial views of Berlin, a city here reduced to rubble in the wake of war as the frenzied soundscape gives way to the single violin tone of the film’s beginning. And like its opening, the camera surveys its subject in a step motion aerial survey, the surveillance of its track, and its frank opine of a ruined history, evoked here in their domestic rituals. A powerfully elegant join of European ennui and the shattered memories that lie behind it, Continental Breakfast’s slow motion attention to detail and crisp montage would propel Müller’s narrow gauge efforts into an increasingly personal arena.

Final Cut (12 min 1986) was completed the next year, and proceeds by synecdoche, by a collection of small gestures in the present posed against a backdrop of home movies. Its opening window drape re-marks its express intention: to re-stage his own family within his apartment confines. Against a black surround a small rectangular aperture admits images of familial mirth, a parade of long past smiles shuffle past as elders join again in a communion only possible now as an image. The drape recurs, then a fragmented montage of a pitcher of milk and flower vase. The pitcher pours into a glass too small to contain its contents, emblem here of a generational legacy too vast to be restored, while the flowers, an image of nature, is domesticated and arranged in a vase. Seething close-ups of flowers follow, their crimson flicker remarking their wilder origins. Brooding music punctuates the track while a series of anonymous figures, rephotographed onto textured screens, traverse a looming urban decay. Architectural details ensue, possible sites for revisitation, moments of roof and tile conjoining to produce a feeling of oppression in the perfectly ordered cities of the modern. A series of theme and variations, again rendered through re-photography, replay a moment’s traversal of a stoplight, cyclists halting, racing past, glimpsed again in the overexposed glare of the projector, moving forwards and backwards, this temporal play of reversal a temporary salve for a filmmaker trying to thwart the inexorably forward flow of time. Another flurry of montage recapitulates the film’s preceding sections, summoning the tropes of its own history before adding new sites of visitation. These street moments are precisely framed and primary coloured, their very newness a sign that these have all been erected since the war, that these dreams of order have been founded on the carnage of generations past, their rationalist aspirations containing the seeds of the architecture which has succeeded them. A red sea follows, the filmmaker’s mother bathing at sunset, her surround transformed into a vast spill of blood, as if she were bathing in the runes of history itself. The filmmaker’s single frame re-projection produces an agitated summary, even as the film’s material, here the medium of memory, threatens to collapse altogether. Even as recurrent images of a swimmer promises relief we glimpse a man turning towards a barred window, a prisoner of his own memories, and opens blinds, while the emulsion begins a rapid burn, lending fire to these recollections. Final Cut refers to the filmer’s open home movies, taking them in hand he is able, at last, to have the ‘final cut’. But even as he moves to control a legacy of familial images he finds himself washed over in the blood they denote, the past a litany of those no longer alive, the materials of remembrance themselves subject to the very decay they denote.

Epilog (16 min 1987) was made with fellow Alte Kinder filmer Christiane Heuwinkel, the blank faced star of Continental Breakfast. Awash in the heightened grain and crimson hues of re-photography, it features a young child’s visions which are strained through the ‘cost’ of memory, the immolation of the film transport itself. Its opening features a pulsing figure walking away from the camera while a debris of tail leader flickers past, these images marked by the signs of their own material finitude. The boy approaches a wall and peers through it, a narrative ruse which frames and occasions much of the film’s imagery. He watches children at play in a scope format frame derived from re-photography, their figures appearing and disappearing in a balletic chase. Mounting three projectors side by each, the filmmakers then serve up a man walking past a classical architecture before the boy leaves, walking into a hazy crimson field in which he is unutterably alone. His footfalls appear on cobblestones, and then appear again in a multi-screen format, clearly he has entered the arena of projection, his traversal of the image world yoked to his capacity for wonder. A long walk through night ensues, shadows and ladders overlooking his crimson retreat. Other figures appear in silhouette, possessed of an auratic luminosity, fairly glowing in the dark of their surround. Now the boy walks once more, eventually into a slowly pulsing red field to gaze once more into the wall which divides him from discovery. Müller appears next, holding hands to face, turning in bed while childhood shadows dance past. A pulsing and dissolving compendium of factory interiors, industrial signage and metallic columns follow, the signage appearing as aged and inscrutable as any Egyptian hieroglyph. Here, the film begins to burn, then images of Müller burn, his repose in sleep contrasted by the agitated auto-mutilation of the film strip. Film signage is supered over crimson moments of terror, smoke and screaming faces, joining the materials of representation with this dance of death, both managing to evoke childhood’s end. At last the boy walks away, leaving the wall and returning to a home that can never look the same.

The film’s gestures of re-photography serve to abstract and alienate its ‘original’ footage, reconvening it within a boy’s daydream of ending. The wall’s aperture, which admits his initiation into mortality, serves as a narrative frame for the abstract travelogues to follow, as the long dream of death staggers through streets glimpsed in a pulsing and blood red vision. Far from a childhood’s return to some lost innocence, Müller and Heuwinkel here insist that insofar as a child is able to remember, to share the collective dream of history, they are inextricably linked to worlds already past, to the march of the dead.

Aus Der Ferne (The Memo Book) (27 min 1989) is Müller’s lyric opus, a compendium of a decade’s work in super-8. It gathers his rigorous compositions and exquisite framings and summons them in the service of a resolutely first person cinema. Occasioned by a former lover’s death of AIDS, Aus Der Ferne is suffused with images of mourning and melancholy, haunted throughout by a keen sense of the maker’s own mortality. Humanity is here rendered as an anonymous troop of shadows, blinkered marchers striding past monuments to the dead world. The filmmaker enters a dark wood, constructed entirely in his Bielefeld apartment, his youthful countenance re-marking these scenes as a threshold between innocence and experience. And throughout these midnight travails a luxuriant sensuality holds forth, fleshy close-ups intermingle with fabulously glowing icons, the movement into mourning marked by a pronounced erotic charge. The film depicts Müller’s retreat from the world, shuddering past window light, and his entry into his own body. There, bedridden with the paralyzing knowledge that he too might be sick, he begins to conjure his friend in a succession of palatial revisitations, conjuring the erotic allure of his love, and the dizzying descent into infirmity which followed. In the end Müller passes once more from the dark underworld into light, staggering past broken fences and tramwalls to make his peace with the everyday, waking one morning to find himself, to his own astonishment, still alive.

Home Stories (6 min 1990) would prove to be Müller’s most enduringly popular film. Comprised entirely of 1950s Hollywood extracts, it manages both an elegant deconstruction of its original while it reforms these fragments into a haunting medley of domestic terrors. Its approach is clearly structural, not in the architectonic sense that Sitney popularized to describe a genre of conceptual filmmaking, but in its earlier, anthropological sense. Discreet categories of activity have been lifted from their originals, all re-viewing women: peering out windows, running past emptied halls, anxiously turning heads. Ingeniously, and with the painstaking craft that marks all his practise, Müller blends these moments into a single, unified story, utilizing the implied causality of traditional montage’s shot-reaction shot structure to join these disparate architectures. Stripped of their original narratives, these fragments remain nonetheless charged with melodrama and suspense, their stiffly deliberate blocking aiming their protagonists towards the expression of a single heightened emotion. In their originals these moments, and these women, have been used to portray the careening id which their male counterparts keep studiously in check. Here the original narratives have dissolved into the architectures of their surround which vibrate with a palpable sense of menace. With all of its grand Technicolor interiors scrubbed to a uniform shine – one can hardly imagine shrines like these producing anything so mundane as litter – Müller reconvenes the home as an architecture designed to contain female desire. His persistent use of frames within frames underscore the fray – doorways, windows and headboards crowd the composition – lending a keen sense of visual enclosure. The framing provided by home allows women to become visible but only via the means of their own entrapment, only within the context of their own closeted retreats.

Sleepy Haven (15 min 1993) is a long daydream of a film, comprised of a blend of home movie inserts and found footage. Fueled by Dirk Schaefer’s aching string sample, Sleepy Haven utilizes the fade to mime a boat’s rocking passage, opening and closing successive passages with an ebbing flow of light. It is a somnambulist’s reverie, replete with a muscled iconography of sleepy sailors, their masculine fraternity lying in repose. Their countenance is galvanized by the filmmaker’s bathtub processing, imparting to the emulsion’s surface a seething, crackling skin, converting the film’s transport into a vast teeming ground. Its mottled, fissured surfaces resemble nothing so much as a body, its solarized apertures imparting a hallucinatory beauty which threatens always to break apart entirely, the skin of its material support pitilessly stretched across their fantastical recline. Begun with a careful emission of nautical details, moments of rigging, masts and mooring give way to hammocked sailors cribbed from Eisenstein’s Potemkin, their benetted forms conjuring a frankly phallic iconography. A montage of sleepers follow, their burgeoning physiques ample demonstration that these are mid-labor idylls, moments retired from the compulsive motor of the everyday. Asleep, the body offers itself up to the gaze of its beholder, the film’s daydream structure suggesting that their minds are elsewhere, drifted far from these emptied tissues and ligaments, the better to offer themselves as vehicles of fantasy and projection. It is in the very absence of their activity that they may be reconfigured in Müller’s homo-erotic reveries, these sleepers granted a common dream of fraternity.

As the camera browses over another nautical hulk, the high contrast of its rephotography serves to deepen each muscular contour, re-marking the body as a succession of plates, a geography of parts. Interleaved with his torso are recurrent meditations of another order, a deep fissure in rock which is explored and then pried apart by a pair of probing hands. Müller’s insistent intercutting makes it appear as if the man’s chest has been entered, this fantasy object now made to reveal its interior longings. Müller then inserts himself into the fray via re-photography, shooting a tightrope walker off his TV screen while he plants his feet against the glass. Onscreen a man struggles for his footing as he tiptoes over a torrential waterfall, any slip portending certain death. Müller’s insertion underscores his own stake in all this, he too is trying to keep his footing, but the deadly currents which swarm beneath belong to a world of images, not of geography. His agon throughout is with these phantoms of desire, and the escape they denote, the lure of going “to sea”, of abandoning himself to the dissolute recline of his fantasies. The long dream of the image world, depicted here as a reverie in stasis, a ‘sleepy haven’, is both conjured and deconstructed, made to reveal the stress fractures which result when the aims of everyday life are made to rub up against the dream factory.

Scattering Stars (2 min 1994) is a paen to light, a glittering bodice of a film that rapturously unfolds its subject with a shimmering luminosity. Photographed in a luminously grainy super-8, its depiction of an orgasmic fireworks display, rendered here in monochromatic explosions of light and dark, underscores a furtive male passion, bodies glimpsed in retreat in the fulsome shadows of boy-boy love. From an unrelieved darkness a match is struck, inaugurating a fireworks display, and then twin shots of two men, naked and sweaty, looking up. One is the filmmaker and the other his partner in this solarized tryst, reading in the signs overhead an image of their own passion. A cock tattoo interjects, and then a frenetic montage of bodily parts, moments of flesh too close to discern identities and borders. Briefly repeating shots of a man cloaked in shadows, his hand hovering over his sex punctuates the scene, until the film closes with a silhouette of two hands opening accompanied by a child’s wind-up toy – signaling a surrender to these dark desires, this orgasmic tryst.

Alpsee (15 min 1994) is Müller’s latest offering, a revisitation of the filmer’s own Final Cut, rendered now in an elegant, high-gloss style and shimmering colour palette learned from the 50s. Like Final Cut, Alpsee turns about the relation of mother and son, but while the former devolves into a granular first person universe, the latter utilizes dramatic rhetoric to narrate the rhythmic interplay between a young boy’s longing and his maternal filigree. It opens with a collection of Technicolor home movies, young women caught in the throes of graduation, being led by their elders past the threshold of their own childhood. The image ripples and waves, subject to electronic re-processing, a subtle movement of undulation which gives way to the film’s next image – a long theatrical drape which fills the frame. Müller attaches the drape’s monochromatic insistence with the dress of the mother, glimpsed in close-up, who then retreats from the camera. She tries on a ring before the blue drapes appear once more, opening to reveal a young child. Again, the mother’s blue dress floats through the living room as she puts on a record, dusts, and closes cupboards in a percussive polyphony that makes of these home-made gestures a symphony of the domestic. She irons, puts cherries on a pie and continues to close cupboards until the camera floats away to a television in a dark and neighboring room. It shows an operation, the flesh torn away to reveal pulsing organs, with a voice blandly intoning, “What we have here is a human heart”. The boy opens a small box which contains porcelain figures of a married couple, an iconic reminder of life as it was meant to be, which underscores the absence of the father in their life together. The boy retires to read through an encyclopedia filled with images of trees – family trees perhaps – before a space movie interrupts, astronauts look on in astonishment as a plant takes flower. “Watch this! A flower has grown on planet Mars! It’s a miracle.” These dreams of space prompt him towards his own dream of horticulture. Alone, in a vast forest, he secures his own plant, wondering if the distance between ancestors has converted his family into something as alien as Mars. Later, his mother pours off a glass of milk which soon overflows, unable to embrace the contents of the pitcher. This scene is lifted directly from Final Cut, though its significance is clearer here. The milk is emblematic of all his mother will pass on, but he isn’t ready yet, his glass is still too small, so the milk spills everywhere – running over the smooth chromatic surfaces of the table, floor and stairs, and finally engulfing the whole house. This imaginary lapse is abruptly arrested as he is glimpsed again, trying to join the pieces of the broken pitcher, attempting to restore an original wholeness, broken now in the absence of his father. From the pitcher he turns to a jigsaw puzzle, its small inscrutable fragments an ensign for his own confused responsibilities. At night, as the mother again closes shutters and doors in rhythmic proliferation, he watches a growing stain seep across his bed, before he enters into it and begins again to dream. His imaginary carries him to a blackboard filled with starry charts and astronomical signs before he floats skywards, into unknown moons and galaxies. There he presides over a starry found footage montage of mothers and sons, each mother clutching their son lovingly to their breast. The next day he walks with a floral bouquet and lays it on his mother’s blue dress and the mother appears a last time standing before curtains, now changed in colour from blue to red before the film’s last shot – a woman bathing in a uniformly red sea.

Photographed with an exquisite eye for interiors and a restless invention, Alpsee stages a boy’s coming of age, that painful rend between infant dependency and mature individuation. Nearly wordless, Müller proceeds by analogy and synecdoche, gathering up precisely framed moments within the home and collecting them as evidence. Its gorgeous chromatic scheme and high key lighting mark a significant departure from Müller’s narrow gauge efforts of the 80s, yet he maintains his characteristic syncopation, his grand eye for detail, and his resolute focus on the traumas underlying his subject. Like the blank couple of Continental Breakfast, the young boy in Final Cut, the shadowy figures in Epilog and Aus Der Ferne, Müller reinvests the everyday with a trauma that is alternately historical and familial. That his empathy with his subjects is so perfectly borne into the apparatus of a materialist film practise, makes him one of the fringe’s most powerful and most perfect makers.

Originally published in Millennium Film Journal No. 30/31, Fall 1997

The Cinema of Difference by Matthias Müller

In speaking of experimental cinema one refers to a genre that is not a genre. The term attempts to draw together films of opposing tempers into a single species. Material films, found footage films, hand-made films, structural films, a broad variety of surrealistic films, diary projects and hybrid forms are subsumed beneath this vague penumbra. Debates round the bloodlessness of our naming are as old and stereotypical as the term itself, which is used here despite its uneasy hold.

In the public consciousness experimental film doesn’t exist at all. Its mention might conjure visions of crude, pretentious artifacts whose grand ambitions have put theory in the place of action. It has been accused of practicing the most grotesque kind of self love, of exaggerating the consciousness of its form, of mannerism. While largely unspoken, all this remains connected to the term. In a time of elaborate virtual worlds and computer generated consciousness, experimental films seem like relics of a bygone age, archival work from the stone age of the moving image. While the experimental filmer “is busily ana-logging 101 years of swirling bromide, the rest of the world has already moved on into the cold digitzed hell that awaits the lovers of the Magic Lantern.” (Phil Solomon)

Homeless from its outset, treated as a footnote to official film histories, removed from the visual arts where it has historically derived its aesthetic impetus, it has been pushed to new margins and new responsibilities. Ignored by the film industry and its critics, experimental cinema has long labored against its complete disappearance from the public sphere.

It has no fixed address, no home, and no single identifying feature. But it favors the precision, the dense intensity of the short form. There are only a few experimental films of feature length, and these are often based on literary patterns, its segments unfolding like chapters in a book, like Werner Nekes’ Uliisses. Or they are composed in mosaic fragments, like Mara Mattuschka’s Loading Ludwig or Michael Brynntrup’s Jesus-Der Film. The analogy between experimental cinema and the lyric form in poetry has been often remarked. In both, the expression of the Imaginary is primary. Both generate a form of their own, sui generis, and a language which breaks with conventional syntax. Both forms require an active recipient who completes the empty spaces in these works.

The short form is the chosen home of experimental film. Perversely, these films are rarely seen at large short film festivals like Clermont-Ferrand or Tampere. At these celebrations the near exclusive interest of the organizers is dedicated to short dramatic work. Experimental films are commonly sequestered in special programs held in the margins of the festival, or else ignored altogether. The entry forms of most short festivals have categories for animation, drama and documentary, but neglect innovative or hybrid forms.

Experimental filmmakers are notorious individualists, which might account for their failures to lobby on behalf of their own. There are no systems of distribution and exhibition here, no equivalent to distribution initiatives like Canyon Cinema, Light Cone or Sixpack Film (Vienna). Recently in Frankfurt, the Initiative Experimentalfilm was founded whose expressed goal, amongst others, was the creation of a central data bank for experimental cinema. If experimental film does not want to degenerate in splendid isolation it needs such activities, to lend to its distribution some of the insight and invention that has gone into its making.

In the early 80s Germany was blessed with a vigorous distribution network and a high standard of experimental cinema, both blossoming unexpectedly. The movement was viral, pervasive, and spread with an impetus that tried to define its project anew, leaving in its wake the tired, stylistic exercises of “classical” experimental film. This had been a cinema “eager to teach new ways of seeing and to instruct a course in the new grammar, the new language of vision.” (Dietrich Kuhlbrodt) Stridently dogmatic, lacking effect and scarcely shown, the experimental film of the 70s had retreated into the protective bunkers of the museum. Its practitioners sought to erase all narrative elements, embracing instead a practise which referred only to itself, like a filmic boomerang, its cryptic insignias securing its withdrawal into the vaults of modernity, far from the prying eyes of the public.

By the early 80s, the preserves of a removed aestheticism had closed, production increasingly determined by a radical subjectivity less theoretically determined than ever before. The author occupied the centre of this work, the necessities of their lives inspiring new forms in film. This interest in the first person “reduces the radius but deepens the perception” (Karsten Witte). New work would freely weave document and fiction, original and appropriated footage, subverting, then renewing paralyzed genres like the orthodox documentary film.

Experimental films of this period established its own homelessness as a program, leaving behind the established places of cinema culture. It could be seen in youth and cultural centres, in clubs and bars, galleries, squats and exclusively devoted super-8 cinemas. Older forms, like the psychodramas of the 40s and 50s were rehabilitated, not in service of repetition, but a renewal which could maintain lines of tradition without being swallowed by them. The experimental filmmaker travels without map or compass, equally allowed to return to the past or imagine the future. The term of practise shift. Wolfgang Max Faust: “Everyone has to find their own way now… the principle of acceleration inimical to our traditional idea of the avant-garde has vanished”. Sharon Sandusky continues in this vein, exposing the ideology of permanent progress which haunted avant-gardes of the past, reducing them to movements of formal innovation, taking their place in our modernist industrial heritage.

Today filmers revisit the past in order to relieve the tyranny of the present tense, working with found footage to reinvoke histories which can only be understood, only imagined, in the present. Their investigations have helped clear the shelves of the shallow Brakhage imitations passed through exhausted cameras bent on imitating styles, like forgers in a museum.

Expecting breathless technical innovations from experimental film means reducing it to a kind of test laboratory. Or it can be pressed into the service of a narrative cinema, bent on avoiding risk in a relentless presentation of old stories, cannily wrapped in new visual effects. For all that, MTV remains better equipped to create new styles, to evoke a visual sophistry, than any experimental filmmaker.

Amidst growing job insecurities, the upholding of success as the final arbiter of value, the loss of cultural monies, the recourse of the younger generation was the cheap super-8 equipment of their parents. Or some years later, in North America, the use of Fisher Price video cameras, the low-tech children’s toy, provided alternatives to an impasse whose origins are international, but whose effects are felt locally, and with irresistible force. These models of production, inspired by the freedom of the amateur, should not make us believe that more ambitious projects can do without public funding. The image of the camera stylo romanticizes the real situation, covering over the tough, economical reliances of the filmmaker.

The sadness of the world’s creation has little to do with the genesis of experimental film. In this beginning they’ve left the word behind. Experimental films prefer shimmering nuances of meaning to the retelling of stories already known, already understood. They’re created in emotional border territories, spaces between which cannot, or will not, be named. The interest of the experimental filmmaker is rarely dedicated to those phenomena which have found their definitive expression. Instead, they share an interest in ambiguity, in the unsettled states which cannot be classified. In a place which obtains before language. That’s why it’s difficult to present them in conventional screenplay production applications.

This is just part of the “problem” of experimental film. These films invite the audience to an “open and plural reading” (Peter Tscherkassky). A bewildering variety of interpretations announce themselves. On the one hand, a rich complexity, full of nuance and allusion, and on the other, a lack of mass appeal. We are used to being led by the hand of the film’s story, and for the film critic it’s much easier to cling to this storyline than to create a language adequate for new images. Only a handful of curators have treated experimental film with the personal urgency that Alf Bold did, the former artistic director of Cinema Arsenal in Berlin, whose efforts on behalf of German experimental film can’t be too highly stated. In community oriented media work, those films are favored which may be easily reduced to a particular message. The easier it is to reduce a film to its “shadow world of messages” (Susan Sontag) the sooner it may be used to underline the already understood, the deja vu of consensus.

Last year in Oberhausen Jonas Mekas presented a program entitled Useless Cinema. Here was a world purged of utility, devoted to all that could not be signed or put to use, whose inhabitants have become hunters of habit. Creating useless things for a filmmaker means settling on the outskirts, the furthest margins of film economies. The experimental filmmaker arrives there, “stowaways on a ship they would rather captain” (Peter Weibel) with impeccable credentials. They continue to make short, formally sophisticated work, narrating subversive or risky themes and produced on substandard, amateur gauges.

The film scientist Christine Noll Brinckmann, considering the marked decrease in production and public visibility of experimental film called this a “phase of sobriety”. Due to waning financial support established festivals like the Bonn Experi and Nixperi have long ceased to exist. Others, like the Osnabrück Festival that started as an experimental film workshop in the early 80s, have shifted focus to a broad area of media art. Arte’s Snark TV program, formerly dedicated to innovative shorts, has been replaced by another exhibiting short narratives.

If the experimental short film remains in critical condition there needs still to be discussed the more obvious dilemma and regression of the dramatic short film. These films continue to threaten the survival of a cinema of difference with their relentless mono-culture of repetition, pandering to audiences willing at best to accept short films as appetizers, curtain raisers. Old wine in old bottles.

To demand endangered species status for experimental film would be premature. Many filmers use the present “phase of sobriety” in a constructive way to reconsider past positions in a media landscape that continues to change shape. The real dilemma of experimental film begins after production. So long as the world of visual art stands at one remove, film critics continue to behave as Hollywood taste testers, and theatres/festivals reduce short film to its populist denominator, the survival of experimental film remains in doubt. We are in danger, as Birgit Hein puts it, of losing “a crucial part of our cultural identity”. Yet its homelessness is its chance, for it guarantees the necessary mobility and independence to deal with permanently changing conditions. To forge new alliances, loose new impulses and remain unpredictable.

Remarks on the Diary Film by Matthias Müller

Diary films pinpoint an ‘I’ so omnipresent that the world fades to a mere etcetera. In the diary videos of Nelson Sullivan, for instance, the wide-angle of his hand-held camera seldom allows the maker to slip out of view. Sullivan usually fills the entire image, pushing the reality of the outer world to the edges of the frame. When he tells us, “You can walk in my shoes. I want to share it all with you,” Sullivan reminds us that diary films invite the viewer to visit a private world. “Welcome to my world, won‘t you come on in…” bubbles an old pop song. Formulated in the first person, diary work dialogues with its viewer using the persona of the maker. As film critic Karsten Witte writes, reducing the film’s focus to its maker “limits the radius, but deepens the perception.”

The written diary is usually hidden, sometimes under lock and key, and it seldom leaves the private sphere. By contrast, the diary film is made for dissemination. Both genres involve the author’s interest in recording personal incidents in order to recall patterns of becoming. Me, myself and I: it’s about the questioning, the construction and manifestation of the self. But in the cinema, factors that are irrelevant to the clandestine and private journal may come into play, like vanity, shame, or the consideration of others.

Like any written diary, the diary film is created after the fact; distanced in time from the events described. But in the moment of recording it demands spontaneity and flexibility. Analysis and reflection lend the raw material structure, though editing follows associative connections rather than classical principles of narrative continuity. It is through editing that these ‘objective’ documents transform into fiction, though they may be all the more ‘authentic’ for it.

Diary film makers such as Sadie Benning or George Kuchar employ role-playing, parody, and travesty, as well as thoroughly conventional rules of narration, which often coquette with established film genres, as elements of their work. In his early videos, Kuchar edits much of his material directly in the camera. One senses a boisterous pleasure and virtuosity (resulting from years of experience in working with fictional films) in the dramaturgical editing of his own daily life. As Kuchar suggests, ”Most of us see life in the form of a Hollywood movie anyway. So in diary videos you can add music at just the right time, and orchestrate the shots of mom making potato blintzes so that it looks like she’s in a Brian de Palma movie.”

There is no unifying code that accompanies the autobiography. For instance, Birgit Hein‘s challenging Baby, I Will Make You Sweat (1994) and Michelle Fleming‘s sophisticated Life/Expectancy (1998) are reflections upon the mid-life situations of the authors, and yet worlds lie between these films. Hein defiantly reclaims her right to her own sexuality at the age of fifty-six, simultaneously pushing the limits of “direct cinema.” Fleming’s eclectic montage joins psychoanalytic intertitles, moments of her own life recast as Noir fantasy and the bickering of Taylor and Burton from Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Each maker invents a shape for their own experience, as unique and individual as a thumbprint.

Diary films allow the viewer entrance to private spaces; as Stan Brakhage stated in his essay “In Defense of Amateur,” “I am mostly guided primarily in all creative dimensions by the spirit of the home in which I’m living, by my own very living room“. However, style sheets from the diary film (first-person narrative, hand-held camera, jump cuts, etc.) have drifted into other spheres of making. Faked diary sequences have long been a staple of Hollywood fare where grainy home-movie memories become codes of truth and authenticity. As Godard writes, “In order to make fiction, you have to begin with documentary, and in order to make documentary, you start with fiction.” Yet many diary films are craftless and crude, deliberately unsophisticated. Mainstream audiences often recoil, in part because these films ignore the usual social distance that regulates our dealings with each other.

In accordance with the formula ”low tech, high fidelity,” many makers prefer amateur equipment. Super-8, consumer camcorders, and even the Fisher Price video camera (originally marketed as a children’s toy) have been used to make diary work. Easily obtainable, simple to use, and very mobile, this kind of equipment is ideal for unpredictable, extended projects with minimal budgets. The camera becomes the travel escort, the longtime companion, even bedfellow.

The diary film continues to face accusations that it is little more than a vehicle for narcissistic, egomaniacal self-promotion. In our vicarious-living society, all human interests appear to be represented by others (lobbies, clubs, political institutions). It is considered inappropriate, impolitic even, to speak in the first person. In Anne Charlotte Robertson’s seventeen minute litany Apologies (1983-90), only the author is shown, endless apologizing for taking herself so seriously, for wasting film stock that might be used for more valuable projects, and for robbing the viewers of their precious time. For many diary makers, the need for representation arises out of their absence on the public screen. As Yann Beauvais, curator of the diary film series “Le je filmé” ascertained, directing the camera at oneself is often “the liberating act of an individual, who is normally forced into the social background.” Due to the close relationship they bear to the amateur film, one could think of many film diaries as emancipatory home movies.

Marginalized groups, such as gays and lesbians (Sadie Benning, Su Friedrich, George Kuchar, Nelson Sullivan, Remi Lange), displaced persons and immigrants (Jonas Mekas, Robert Frank, Rudy Burckhardt), or the mentally ill (Anne Charlotte Robertson) formulate commentaries about their lives in diary films. For Robertson, who has been diagnosed as “temporarily mentally disabled,” producing a diary film is a daily therapeutic exercise. She writes, “Making my diary has literally saved my life.” Diary filmmakers use film to oppose their social oblivion, and to show themselves as individuals, as opposed to the case studies rendered by more orthodox documentary practise. They want to oppose a neo-scientific objectivity and all-knowing voice-over with an eccentric subjectivity. Even when they appropriate scientific texts, these films add the personal pronoun. One striking example of this kind of subversion is Birgit Hein’s The Uncanny Women, where the maker borrows from ethnological and psychological texts, but connects them with a decidedly direct, personal an partly obscene language.

Diary films are often studies of memory and family. In the films by Robertson or Frank, which appear improvised, one has the unmediated feel of real time unfolding. But relics of the author’s past — such as mementos of Frank’s dead children — find their way into the lens. In a scene from Frank‘s The Present (1996), the filmmaker’s co-worker attempts to wash the word “memory” (which Frank had written a long time ago) from the studio wall. Frank‘s camera stops when only “me” can still be read.

Lawrence Green‘s Reconstruction (1995) is also a melancholy meditation on memory. With the aid of old home movie clips, the filmmaker conjures up moments from a distant childhood, though this is not an escapist longing for a deceptive idyll. Green allows these images to collide with the report of his sister’s adoption into the family. Held for many years, this secret was uncovered in the making of the film. So these family documents are never quite what they appear to be, and this overturning of heritage and repression is typical of much autobiographical practise.

We are accustomed to images that show the diary filmmaker shouldering the camera in order to begin a journey of discovery. The delegation of camera work, so we imagine, might harm the material’s authenticity. Since the beginning of the 1980s, however, there has been a growing interest in exploring the possibilities offered by found footage. This most anonymous of film processes appears to stand in sharp contrast to projects centered in a unique and steadfast individuality. But those diary films which admit scraps from the media world cast doubt upon the naive belief in the unity of identity. Dissolving the borders between inner and outer worlds, these films place their protagonists in a tense situation between self insistence and the dissolution of self in a surplus of media stimuli. Wallace Stevens writes, “I am what surrounds me.”

In my own films, appropriated material often serves to expand the autobiographical, to tie introspection to a world of collective images – following Derrida: “Meaning is context bound, but context is boundless.”

The Memo Book is my most personal film. It began after a friend died suddenly of AIDS. Working on the film clarified how strongly my own feelings are determined by traditional media images, no matter how toxic these might appear. The fear and self-loathing, the insistent quest for a story (Why did it happen? Why now?) were all borrowed emotions, but no less real. The long period of gathering and revising made it possible to distance myself, to consider my own creations as if they were found in a flea market. This raises the fundamental question of where one’s own images (and one’s own story) begin.

Working on The Memo Book, I recreated myself in crisis, with the camera acting as interlocutor and intermediary. Cameras can change the visible, and restage even the spontaneous and unprepared. Take a diary project such as Sophie Calle’s and Greg Shephard´s Double-Blind – No Sex Last Night (1992), which was conceived as a human experiment with unknown results. Calle drives with a friend across America, trying to persuade him to marry her, and the audience is welcomed as Calle’s accomplice. The camera is used as a magnifying glass to heat up their relationship: its presence fuels the intensity of the clash between the protagonists.

Calle’s controlled abuse of power, that characterizes most of her works, forces us to position ourselves to this video; like most autobiographical works, it also raises crucial moral questions. However, Calle is not just the omnipotent maker in total control, but personally involved into the dynamics of her relationship as a vulnerable, sometimes frustrated, jealous, and weak human being. A similar, yet wordless involvement we can find in Richard Billingham’s documentary of his family’s life in poverty, alcoholism and monotonous domestic activities in Fishtank (1998). What may appear as a voyeuristic and speculative from the outside on first view, turns into an intimate, patient and sometimes tender portrayal of the artist’s mother, father and brother. And – as Michel Tarantino stated – due to Billingham’s personal involvement in the situation depicted we experience that there is a striking difference between life in poverty and a poor life.

The use of the camera as an intrusion into the personal realm evokes the words of Paul Foss when he asks, “Why so many eyes to guarantee that what is seen is not so much the horror enacted, but rather the horror of looking itself?” Yet the shamelessness with which George Kuchar’s camera exposes the artist’s dirty underwear and cruises the men around him produces an openness unattainable through subtler strategies. Using tactics of intrusion, Robert Franks´s insistent, sometimes manipulative questioning of his son Pablo in Conversations in Vermont (1969), or Abraham Ravett´s merciless and unceasing demand that his old mother remember the Holocaust in The March (1999), are painful attempts to drive the exploration of the self to the edges of confrontation with the Other.

Filmmakers have rarely gone as far as Tom Joslin and Mark Massi in traversing the divide between self and the world. In Silverlake Life: The View From Here (1997), the makers document the stages of their death of AIDS, and the strength of their love. Cocteau‘s definition of film as the only art that can show death at work finds its painful confirmation here. When Tom dies, Mark wants to close his eyes, just like in the movies. But this is not possible, because real death is different. In diary films, perhaps we have only the practice of life and death, and as Montaigne ironically instructs us, “To begin depriving death of its greatest advantage over us, let us adopt a way clean contrary to that common one; let us deprive death of its strangeness, let us frequent it, let us get used to it; let us have nothing more often in mind than death… We do not know where death awaits us: so let us wait for it everywhere. To practice death is to practice freedom.” In Silverlake Life: The View From Here, the gap between industrial cinema and the diary film, and between life and death, has seldom been more intensely presented.

Translated by Allison Plath-Moseley

Originally published in Landscape with Shipwreck: The Films of Philip Hoffman, Insomniac Press/Images Festival, Toronto, 2001