Al Razutis: Three Decades of Rage (an interview)

Al Razutis is a Canadian iconoclast, an artist who was instrumental in forming two West Coast film distributors, a short-lived union of Canadian film artists, a production co-op, magazines on fringe film and holography, and who played a role in a much publicized battle with Ontario’s Board of Censors. He has completed some forty-odd films and videos alongside various performances, paintings, holograms, and intermedia productions. While he has worked hard over the years to secure an institutional base for all aspects of fringe cinema, he is better known for his anti-institutional stance. In 1986, at the opening of a new artist-run movie palace, Razutis gave one of his unforgettable performances. Before a shocked crowd he whipped out a spray can and scrawled, “The avant-garde spits in the face of institutional art” on the brand new screen, ruining it forever. His filmwork has long established him as the sultan of collage. Rifling the junk bins of Sunset Boulevard he has patiently re-ordered moments from the history of cinema and allowed them to speak again in startling new ways. These have been compiled in two of his finest moments — Visual Essays, which offers a retinal massage to silent cinema, and Amerika, a three-hour, eighteen-part opera which serves up sex and death in a frothing mediascape. The ability to remember has never looked more dangerous.

AR: I was an undergraduate in San Diego studying chemistry and physics on a basketball scholarship. On my way through the library I noticed a book open on the table. It had a series of colour plates dealing with things I’d never seen before, and the more I flipped through the book the more it enchanted me. What I was looking at was the history of modern art in large colour panels, and that day I went out and bought acrylics, oils, and watercolours, and started painting. I painted for a month and took it to an art teacher who said it was all shit and that I should take an art course, which I did, and got totally bored. I didn’t know why you had to study art because I was experiencing it directly. None of my art ever came out of formal education.

In the late sixties, I started an underground cinema at UC Davis, which is between Sacramento and San Francisco, where I was doing some graduate work in nuclear physics. Then I wanted to expand the underground cinematheque by flying down to San Diego and setting up another one there. I would rent work from Canyon [the distributor], the money would come from the gate, and the audiences were huge. I got my first camera by starting a cinema club at the university, applying for money from the dean, and using it to buy myself a camera. I made my first film there — 2 X 2 (17 min 1967), a dual screen film obviously related to Conner and Warhol. It dealt with sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll, a typical topic in the sixties. When I finished the film all I had was the original, I didn’t know you could make a print then. Some guy in L.A. named Bob Pike was running the Creative Film Society, which distributed a lot of underground work. He said, “I love this film — I’ll buy it — but you have to sell me the original, and if I want to recut it, I can.” I got $2,000, which is when my girlfriend decided to go back to Vancouver, Canada.

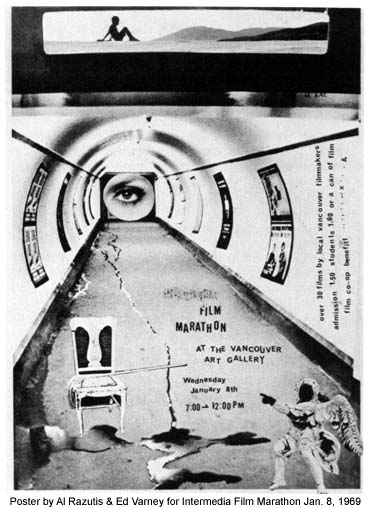

We drove up in 1968. I hooked up with an organization called Intermedia which had a four-storey warehouse on Beatty Street comprised of artists of all disciplines — four floors of free studios, sculptors, dancers, painters. Anybody who was doing crazy, innovative work was doing it there. I convinced them that I could run underground films on the weekend and they said nobody here comes to anything. I asked for the second floor Saturday and Sundays, promising to pay for everything, and I would keep the proceeds. We made hundreds of dollars every weekend — the place was packed. By that time I had some experience of curating for the audience. I never curated auteurs, the Bruce Baillie night or whatever. The audience was interested in looking at the best examples of a certain approach to work.

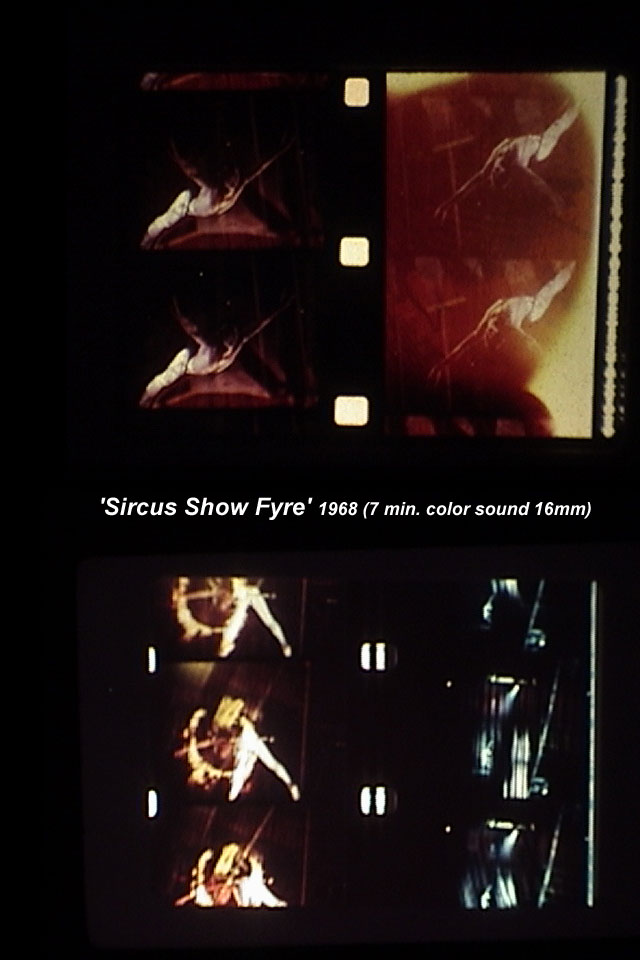

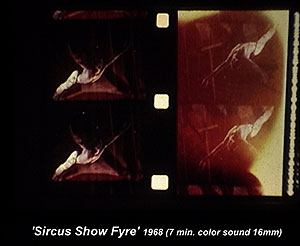

From the money I made showing these films I financed my own films. Intermedia was a place where different sensibilities could rub together without the usual bureaucracies or jealousy. I made a number of films — 2 X 2 became Inauguration (17 min 1968); Sircus Show Fyre (7 min 1968), a film about the spectacle of the circus using four layers of superimposition; Black Angel Flag… Eat (17 min silent 1968) which is mostly black leader with very intermittent shots, so you don’t know when the film is over; and Poem: Elegy For Rose (4 min 1968) which featured a poem written on celluloid. I hated redundant work, which was part of my take against the institution of art. I thought galleries were a total sell-out, and any artist that would create a style was a cop-out. In any formative or dangerous time of making work, the worst thing you can do is bag your own style. I used to call it a paper bag because you’d throw all your shit into it and shake it around, and it would always come out the same. In every work, I’d try to negate what I’d done previously.

MH: Did you feel a split between formal and political moves?

AR: There was no split at all; that’s the thing that was so peculiar and beautiful. This is going to sound extremely sentimental… Take a film like Lapis by James Whitney, for example. It’s a computer graphic mosaic set to sitar music, an abstract film which serves as a meditation on a state of mind. It externalized what some people experienced on LSD. Formally eloquent in its own right, it had a place in a counter-culture drug culture because people were experiencing these things on a daily basis. What they were celebrating was completely connected to their political beliefs, which were similarly anti-establishment. Everyone was trying to break down conventions and look for alternatives to message systems which they’d grown up with, family systems they’d inhabited, professional systems which they were obligated to. That’s why none of this work was touted as art, because the institutions of art were already suspect. How could you reject middle-class America and not reject its art history and universities? The same universities that were teaching a European history of art were teaching the military sciences that fed the war machine.

In the time of Intermedia, there was no connection with grant agencies, art galleries, any institutions of any kind. Later on Michelson, Sitney, and Youngblood began making schools and movements, which was the beginning of the end: its professionalization, anthologization, academicization. Underground film became art, and that was the demise of the form. They made it pedagogical, voyeuristic, and auteur-based. That’s when the rush for the museums began. If you wanted to become a fixture in the museum of the avant-garde, you had to be legitimized somehow. Do you have a large body of work, or how clean is your technique, or how innovative is it, or who would write about you, or where did you show? And that’s part of the difference between then and now — expression didn’t depend on mediating influences twenty years ago. The legitimizing histories offered by film schools are a total distortion of what happened. There’s a lot of people who went through the process and vanished, whose work in its time was just as important as those who are remembered today.

In my weekly screenings at Intermedia I included the work of local people like David Rimmer and Gary Lee Nova and realized that people in Vancouver were starting to make films. So I thought, let’s make a co-op along the lines of and inspired by Canyon or New York Filmmakers. In 1969, I talked to various filmmakers who thought it was a great idea, but they didn’t really have the time, so I said, I’ll do it. I became the founder/manager/bookkeeper/floorsweeper of the Intermedia Film Co-op, and I drew up some packages and toured them down to the US. It was a distribution co-op that held mostly Vancouver work but also others from the US. Like the co-ops in the US, we had no submissions policy; we took whatever people offered. We had an office and published a catalogue with about 100 films in the collection. Most of the work went to cinematheque, underground-type film screenings. There was a network of venues down the Coast which I’d made contact with as a programmer in the US. The only money we could get was what we took from our cut on the rentals. We ran a couple of years, and my energy evaporated because there weren’t enough people willing to go the distance with it.

The birth of the Pacific Cinematheque with Kirk Tougas happened around the time of our demise. He was coming to our screenings and running the Cinema 16 Film Club at the University of British Columbia with an eye to setting up something more permanent. So he started the Pacific Cinematheque, which began screenings in 1971 and is still running today. In 1971, Intermedia moved to another space and new factions grew up which eventually brought the house down. But the different people who left Intermedia formed a number of satellite organizations like Western Front, Video Inn, Intermedia Press and the Grange; so in a sense it evolved, it transformed into these other places. I tried to set up an underground film theatre with Keith Rodan. We had a storefront and built a huge screen and projection booth and pulled some chairs in. We advertised in the Georgia Straight and that’s where we made our mistake. The fire marshal showed up and said he’d been asked by the BC Censor to check the premises, and we got shut down. They just didn’t want us running films. I ran out of money and sold all my equipment. It was a bad time.

There are two people on the institutional side from the late sixties, early seventies, who deserve greater mention. Peter Jones at the National Film Board helped underground filmmakers with stock and processing. He came from the old guard at the Board and had an interest in supporting independent films even though this wasn’t part of its mandate. He would come down to Intermedia and offer people assistance; he was amazing. The other guy was Werner Aellen, who was the director of Intermedia. He was my godfather — got me jobs, lent me money. He kept me going for the year or two when I had nothing. Keith Rodan and I went out to Alaska and made a documentary on the Alaska pipeline.

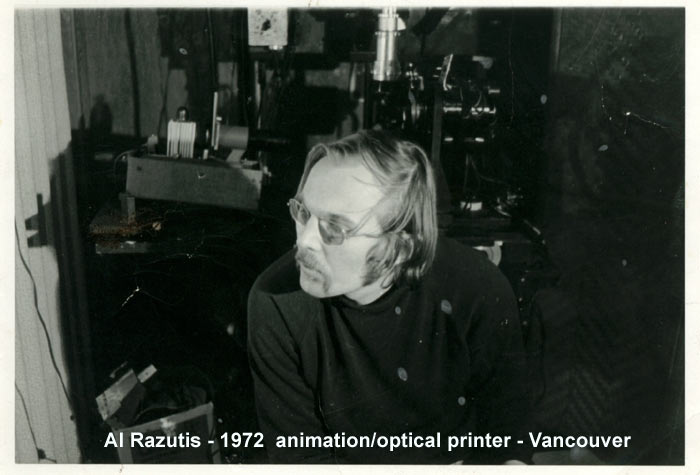

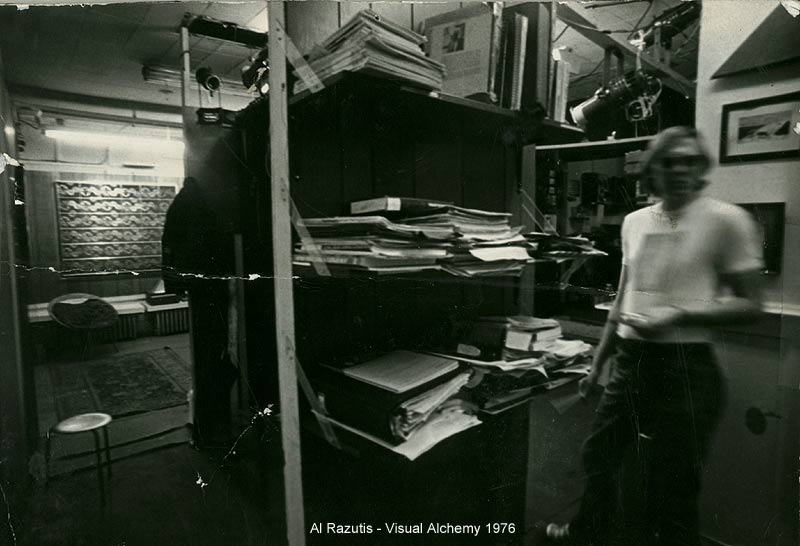

Then suddenly this teaching job appears from Evergreen State College, and that’s when I walked into a Disneyland of equipment: a video studio, all kinds of synthesizers and cameras, and a very interesting academic program. That’s where Amerika started. I made Software, Vortex, and some of the video components of 98.3 KHz: Bridge at Electrical Storm. We were doing bio-feedback experiments at the college — setting up film loops and wiring ourselves into EEG machines in order to induce states of meditation. Then these outputs from the brain were fed through amplifiers and directed into a second monitor which mixed the image signal with those from the brain to see if you could affect the image directly through your response. There were a number of film and video hybrid works begun there. I was contemplating staying on at the college until I made an application to the Canada Council for holography and, astoundingly, they gave me a senior artist’s grant. I don’t know how much money it was then, but it was top of the line, like getting $80,000 today. So I decided to come back to Vancouver, quit teaching, and set up a media studio called Visual Alchemy. I’d finished building an optical printer, built a video synthesizer, had audio equipment, editing rooms, animation stand, a complete holography lab in the back, living quarters, and a projection/living room space. The Canada Council grant paid for some of it, and I started to do optical effects for people for a fee. By 1972, I had the final version of the printer built. Then it became a production machine where I could make special effects for people like Rimmer and Tougas, and I became an optical service for a lot of commercial people. If anybody wanted a freeze-frame they could only get it from me. It was the only optical printer in Vancouver. I rented out my editing facilities and offered courses in holography. I was trying to make a commercial and experimental venture, and the whole system was available for my own work. So it was a very productive place for me, a completely enclosed interior space. Gordon Kidd got his start there. He was an art school student who came over one day, with a rainbow-coloured bow tie, asking to be an assistant, and I took him on. His films were made at Visual Alchemy.

I created Le Voyage, Visual Alchemy, Portrait, and Amerika was continued with Bridge at Electrical Storm. 98.3 KHz Bridge at Electrical Storm (11 min 1973) was contrived on the optical printer at Visual Alchemy. An extremely laborious film, it was created one frame at a time; sometimes twelve frames would take over an hour to do because it had so much bi-packing and combinations of film and video. The video was transferred to film which was then reprocessed on the printer. When Bridge came out, some people from Belgium looked at it and said, “That’s not film, it’s video.” For them, legitimate film practice had nothing to do with video. But I kept trying to exchange formal values between the two, trying to achieve new forms of film and video making. But the film/video hybrid was not an acceptable form. The policy of Canada Council was that video synthesis was not art. They accepted conceptual video, the beginnings of narrative video, drag queen video and Toronto video. My work in holography had a parallel to my work in video in that it didn’t have a place in contemporary practice. Most people were doing toy trains and broken wine glasses, and I was trying to integrate sculpture and holography, making a number of interdisciplinary gestures. I didn’t have much contact with the holographic community because I thought their work was shit, and they couldn’t understand what I was doing. So I was having problems with filmmakers because I was using video; I wasn’t accepted as a videomaker because they said it was all done on film; and the holographers said my work wasn’t pure holography. It allowed me a kind of escape from the containers of arts and institutions, and the acclaim people try to achieve early in their careers without doing the work, all of which tended to perpetuate an alienation and anti-social strategy I’ve already remarked on.

While most of the films made in this period ended up in Amerika, there were some autonomous works like Portrait (8 min 1976). It’s a study of my two-year-old daughter, Alicia. I made a kind of pointillist examination of her by magnifying the super-8 grain through generations of rephotography. I used a saccadic process to re-scan the image. The eye scans an image, and remembers this scan pattern which is called “feature rings.” This is the basis of our visual memory. The second time we see something, we remember it according to this feature ring. So I was trying to create a new way of looking at essentially repeating images. My wife and I had broken up, and I was moved to make this film through the loss of my daughter.

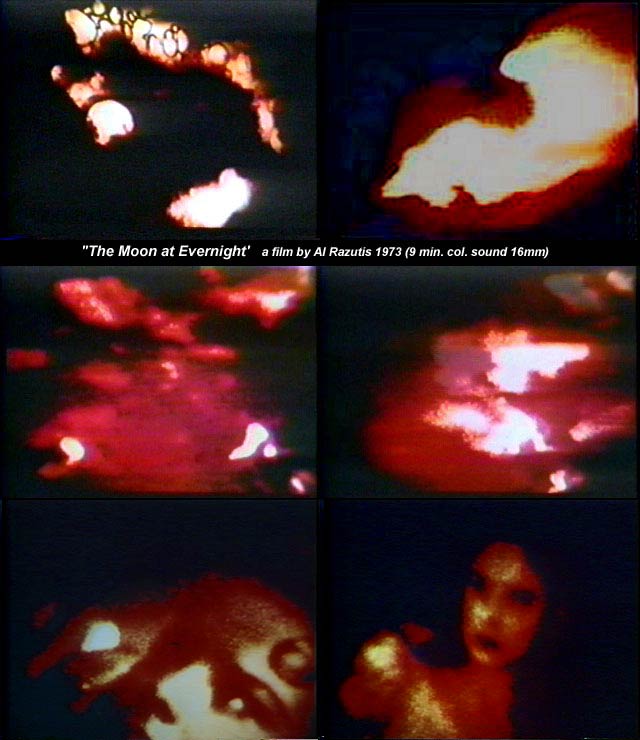

Le Voyage (8 min 1973) was done as a further exploration of black leader and image/sound discontinuity. The title recalls Méliès’s Voyage to the Moon, which was, for me, a voyage into the unconscious. The image shows an optically refigured ship in a storm that appears intermittently, between irregular lengths of darkness which are used as duration, spacing, and erasure. Its discontinuity gives a sense of arrested process, of subconscious recollection. There was also The Moon at Evernight (9 min 1974), which explored abstraction and subliminal imagery.

MH: Many of the films from this period evince structural concerns. They show a contained figure which is made to move through a series of themes and variations.

AR: I think I was more interested in the structure of cognition and in liberating the unconscious processes filmically. I wasn’t interested in the machine of cinema — the zoom lens or the long tracking shot. We had long parties, some substance abuse; it was a very intense period that lasted from 1972 to 1977. We were going out on the streets and projecting films on billboards. Gary Lee Nova and I had a screening on the front of the Scientology building, projecting the most violent images we had while they were having their big meeting inside. In 1976, I launched a one-man show of holograms. Then I applied to the Canada Council to finish Amerika. I’d finished a dozen fragments, and all I wanted was stock and processing. They rejected it, and I went bananas. Later on I found out who was on the jury and I was going to punch out Peter Bryant, who sat on the jury, at this party in Vancouver. Picard intervened. Gary Lee Nova and I were behaving like gangsters, which probably had to do with overwork, stress, and generally inflated egos, right? Anyways, I burned out, didn’t get my grant, finished my holography and film work, and decided to go to the South Pacific. I started to sell all my equipment. I took all my stock footage and shipped it down to Los Angeles and what I couldn’t sell, I left in the studio. I left a key under the mat and told all my friends to help themselves. I just walked from the whole scene with my second wife. Off we went to Samoa, and I never wanted to come back to North America; I thought it was all bullshit. I didn’t want to have anything to do with any technical forms. I just wanted to write novels. In Samoa, I taught high school math. A year later I received a message out of the blue asking me to teach film at Simon Fraser University, so we headed back to Vancouver.

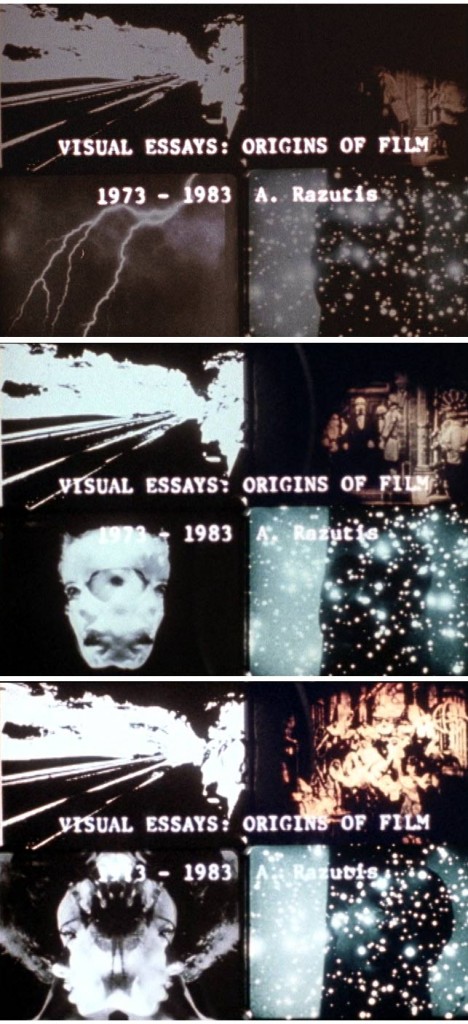

This was the beginning of my political phase, because I realized you can’t hide from North America and that it was possible to work in institutions. There was a compulsion to explore new things, and to realize there’s another form in which you can keep going. And that started a new cycle of works which runs from 1978 to 1987, another nine-year cycle. When that ended, I left Canada again and headed south to live in Mexico. When I got back to Vancouver from Samoa in 1979, I began work on a series of films that would restage moments in film history — and these became Visual Essays: Origins of Film (68 min 1973-84). They deal with filmmakers like the Lumières, George Méliès, the Surrealists, and Sergei Eisenstein. Each film reworks found footage according to a dominant formal strategy.

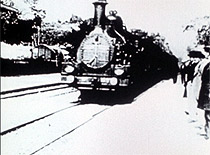

The first essay Lumière’s Train (Arriving at the Station) (9 min b/w 1979) concerns itself primarily with the mechanistic quality of cinema. The Lumières were concerned with creating a motion picture record without being overly concerned about further refinements, usually shooting single-reel films from a fixed vantage. What they were presenting were the effects of their invention, the magic of sequential movement. I chose three sources that dealt with trains: the first Lumière film, Abel Gance’s La Roue, and a Warner Brothers short, Spills for Thrills. The film begins with a series of freeze frames with these three-frame aperture opening and closings, so the image seems to breathe a little, and then the train begins to move, the images link one to another, and motion is born. The Lumière film is subject to stop-motion printing which slows it down, and the image rapidly alternates between negative and positive, creating an optical effect where the viewer is made more aware of the intermittent quality of the motion picture image. I used the sound from train recordings to produce a rhythmic pulse against which the image could be measured, especially as it’s changing speeds through the step printing. The sound conceptually stands in for sprocket holes. It speaks of the mechanical universe the Lumière brothers created. The narrative elements introduced are consistent with this mechanical universe — they introduce spectacle. Whether recording fiction or documentary, the apparatus leans toward the larger-than-life, the extraordinary versus the mundane. Abel Gance’s film is explicit on this point, showing a train derail at the station and unleashing havoc in every direction. The Warner Brothers film is a series of stunts which show trains crashing into cars, chases, special effects. Which goes back to the story of the first projection — the story has it that Lumière’s film was mistaken for a camera obscura, and upon seeing a train come into the station, the audience leapt from their chairs to avoid being hit. Similar incidents were reported in Canada. But after the initial shock of motion is over, the medium has to reach for this feeling in other ways.

MH: Are you suggesting that Lumière’s first film unleashes a spectacle of destruction that naturally follows the invention of motion pictures?

AR: Realist cinema was headed towards hyper-reality and greater impact. The audience demands that the value of the spectacle be increased for every generation — creating vistas which are more than real.

MH: It’s an interesting idea in the face of Noel Burch’s theory of the development of cinema. He describes the socalled “primitive” period (1895-1905) as an Edenic mixture of styles and genres which was appropriated by American business and recast into illustrations of nineteenth century literature — this progression follows McLuhan’s dictum that each new medium will take on the content of the last one. And it’s here that film is subject to a rigidly defined series of encodings: the shot/reverse shot ploy, spatial continuity, following the action axis, matching eyeline glances, all of the dramatic baggage that continues to inform the passage of the movies. What you’re suggesting is that some of these propensities existed from the very beginning.

AR: When George Méliès arrived looking for a way to spruce up his magic act, the Lumières told him it was an invention without a future. The second film in Visual Essays is called Méliès Catalogue (9 min silent 1973). I’d collected a number of Méliès films, which were part of a piracy network that people were lifting from the Cinémathèque in Paris, and I was concerned that none of this work would be seen. I wanted to create a kind of Sears Catalogue celebrating the mythic, visual vocabulary of Méliès. His films contained an overriding quality of surprise, shock, and spectacle that naturally extended from his work as a stage magician. Many of his stage techniques were utilized in film — like appearance/disappearance, levitation, or instant transformations, which he used in imagery borrowed from classical mythology. I wanted to make a film that could accompany screenings of his films. It’s not an academic treatment of the material; it’s poetic and personal. I wanted to internalize, ingest, and recreate it.

MH: The images are framed inside burning celluloid, the dominant formal motif of this film. Why the burning?

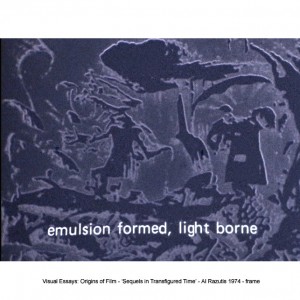

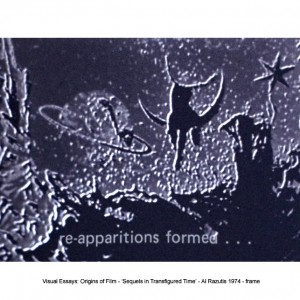

AR: Because his work was done on a very flammable nitrate stock, much of which was lost or simply disintegrated. He went broke during the First World War, and the government seized his studio and converted his films into industrial cellulose which was made into shoes for the army. The third of the Essays also concerns Méliès. It’s called Sequels in Transfigured Time (12 min silent 1976) and works to interpret his mise-en-scène. I used a bi-pack technique, running a mid-contrast colour stock with a high contrast black-and-white negative. Their slight off-register reduces an image to its edges, so as the film begins you’re looking at what seems like cave paintings, or stained glass, but it’s only lines. Then out of that you’re encouraged to discover the mise-en-scène, and this happens as the freeze frames which begin the film accelerate into motion, so the viewer can synthesize a landscape. Often the film will slow down to reveal Méliès’s invisible cuts, where he turns an omnibus into a hearse or midgets into puffs of smoke. I wanted to show how he’s making the transformations. There’s a series of subtitles that narrate an elegy I wrote for Méliès. It closes with a passage where Méliès, as a necromancer, dances before a pyramid in order to raise a spirit from the dead. The spirit is conjured, growing finally into a twenty-foot mass before leaving as I recite the elegy, and the film ends. We saw a magic act a week ago which is exactly the same, where a guy grows inside a shroud. It all goes back to Méliès and beyond.

Ghost:Image (12 min b/w silent 1976-79) is the next film. Its dominant strategy is the Rorschach produced when images are mirror printed, the original image superimposed over itself in reverse. As these two images come together, they create a new space between them, a dark interior that needs to be read in a new way. These were isolated with some primitive rotoscoping I did, projecting onto a mirror which beamed the image up to a sheet of paper, and drawn one frame at a time, then rephotographed onto high-contrast stock to produce the cut-out mattes for the film. The film describes a narrative trajectory that runs from surreal films like Un Chien Andalou, Ghosts Before Breakfast and The Seashell and the Clergymen, to German expressionist films like Nosferatu and concludes with more contemporary horror films. All of these images are suggestive of interior states, extreme states of psychosis. For the surrealists, this was a wealth of information that occasioned celebration and the derivation of new forms. But this process degenerated in horror films, until the unconscious became something to be feared, something that could be transformed in terrifying ways; finally the viewer was positioned as an object of attack.

Ghost:Image describes this process of degeneration — from Surrealism to horror films, from representation about a filmmaker, but about a practice more closely associated with theatre — Antonin Artaud and his theatre of cruelty. He released a series of manifestos designed to rid the theatre of its reliance on literary forms and return it to a ritualized state of trance, ecstasy, and madness. I wanted to create a piece that would speak of the self-destructive urge motivating many of the German expressionist films. I wanted to explore this from a poetic perspective and recreate a kind of madness, a cacophony of voices, a situation of heightened anxiety which would be incorporated with its filmic equivalents. I began with Dreyer’s Joan of Arc, which is concerned about Joan’s possession by what she claims to be angels, but which many others take to be satanic beings. Her only sympathizer is a young priest, played by Artaud. In For Artaud I used a bipacking technique similar to Software, where I photographed the white noise from a television set, controlling the number of dots by cranking the white level. This was then used as a matte for Dreyer’s images, which grow more visible as the exposure on the matte is increased,causing halation and a starry quality to the image. The soundtrack is a group of people chanting phrases like, “We are the inquisition — speak,” and a fragmented monologue from Artaud’s writing (“Shit to the spirit”) which was then cut up and electronically transformed so the words are rendered unintelligible. It closes with a section entitled “Wedding for Artaud” which shows an immolation; this time it’s not Joan who will burn at the stake, but Artaud. The only way this cycle of madness could be completed would be to have the protagonist burned alive with anyone else they could draw into the fire. It’s a marriage of your Other through fire. It’s a union that’s only possible through death, which is the underlying expression of Artaud and that cultural tradition. Artaud could only create his state beyond the logos, which is madness, and beyond madness there’s only death.

MH: You begin with a photo portrait of Artaud and zoom in, and as one of his eyes fill the frame, the dotmatte begins to take over, as if he’s dissolving into the material itself. He’s returned to a ruined and fragmented state, a consciousness scattered across the cosmos, madness. The voice seems to function in the same way — an electronic cacophony that seems to move with the dots in a guttural cadence that exists before or after language, as if the whole body were speaking at once, its hierarchy of organs and senses abandoned.

AR: These dots form themselves around faces which become more and less visible as I’m overexposing the matte and allowing the faces to burn through. I show inquisitors and priests, forces of death and redemption, in order to establish the collapse of a moral order. I’m not happy with the piece these days because it’s too long, it’s too structural, and has nowhere to go. It’s an echo that keeps reverberating and how long can you keep hearing it?

The sixth and final essay is called Storming the Winter Palace (16 min b/w 1984). It replays the films of Sergei Eisenstein. I’ve always been fascinated by the whole issue of didactic, political cinema and the way it’s been the subject of a historical revisionism, which sees it as little more than a series of formal gestures rather than for its political context. The intent of this essay was to reintroduce the political stature of the work. The political and the formal operate together in Eisenstein, but the techniques of montage were later adopted and psychologized through Hollywood. The film opens up with sections from October which are shown backwards, and this sequence runs toward an intertitle which reads, “You’re all under arrest.” I think that’s an appropriate conclusion to the Stalinist dictum that affected formalism in general. You will now cease to make work that doesn’t advance the party cause as Stalin sees it. Even in October, which is a chronicle of the Russian Revolution, you’ve got Trotsky and his ilk written out of the film. It’s printed backwards because this whole policy is reactionary — time isn’t marching forwards; we’re going into the dark ages. When you’re working for the boss you’re part of the corporation, and the fact that Eisenstein couldn’t escape those conditions is tough shit; he ended up being a propaganda lackey for Stalin. Stalin authorized the making of his films. Take the story of Alexander Nevsky’s missing reel. There are five reels in the movie, but when you read the script you can see that there’s a reel missing. And the story, as Jay Leyda writes it, is that Eisenstein is sleeping on the editing room floor. Exhausted. Every day he’s editing to an impossible deadline, and one morning these party guys show up and say that Comrade Stalin wants to see the finished film, so they take all the reels except the one that’s sitting on the editing machine. After Joe approves it, Eisenstein can hardly go back to the omnipotent one and say, uh, it’s missing this one reel. Winter Palace examines Eisenstein’s rhetorical strategies. Some are well known, like his montage of conflict, his juxtaposition of opposing elements which is supposed to create a politically enlightened state in the viewer. In the Odessa steps sequence, step printing is employed to show the way in which compositions are generated according to graphic considerations, which probably restates the obvious to film scholars. At the end of the film I go through a saccadic eye movement technique. I start scanning the image itself. I added a texture to the screen so you’re aware you’re scanning an image field, the boundaries of which are uncertain. That was an acknowledgment of Eisenstein’s engineering ideas, which are related to the engineering of perception, which is what saccadic eye movement is all about. Saccadic eye movement is the way we perceive things — when scientists are trying to figure how humans look at an image, able to recognize their feature rings, then how does that implicate duration, which is a critical element in montage? What’s too short an image? What’s too long? All these questions are parts of an engineering issue, the engineering of a political vision. The final sound quote (from Benjamin Buchloh) is about how the work of collage/montage in Surrealism and formalism was appropriated by advertising and propaganda and remains “radical” only in a few instances of the “avantgarde.”

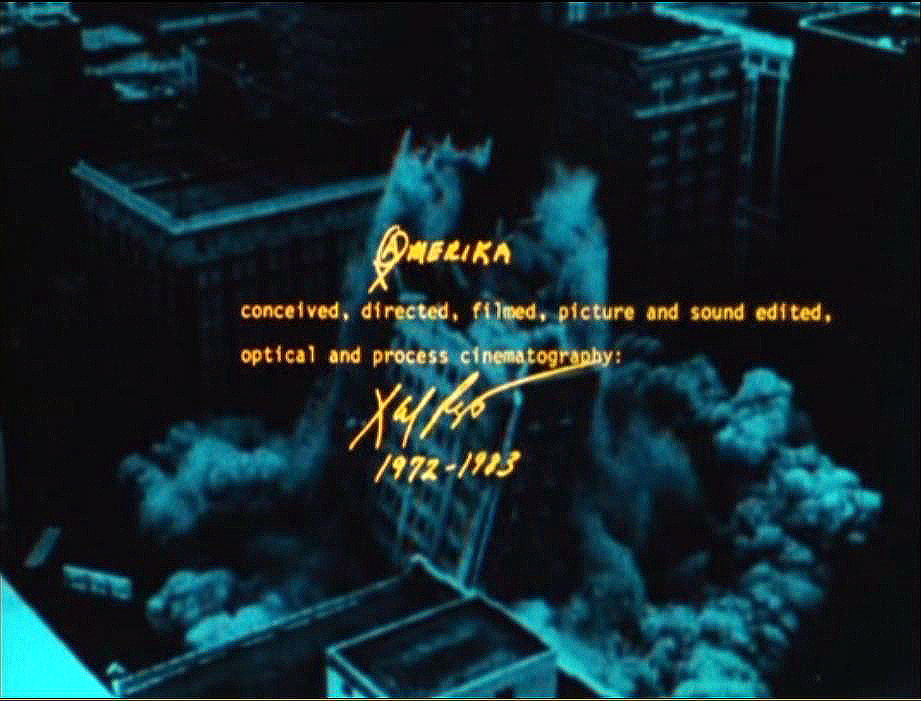

MH: Tell me about Amerika (160 min 1972-83).

AR: For eleven years I made a number of short films which were intended to fit together to produce a single work. It was finished in 1983 and called Amerika. Nearly three hours in length, it’s made up of eighteen short films laid out on three reels which roughly correspond to the sixties, seventies, and eighties. These films are a mosaic expressing the various sensations, myths, and landscapes of the industrialized Western culture. The predominant characteristic of Amerika is that it draws from existing stock-footage archives, the iconography and “memory banks” of a media-excessive culture.

The Cities of Eden (7 min 1976) is the first of the eighteen films that make up Amerika. All of its images derive from the 1895-1905 period, and its formal treatment echoes the disintegration of the nitrate stock employed in this work. I used a bas-relief effect to amplify the fragility of the medium. It closes with the woman from the Paramount logo, which dissolves into an atomic explosion, the first of many “endings” evoked in Amerika. After this annihilation, the second film begins, as if attempting to begin again. Software/Head Title (2.5 min 1972) begins with random noise that slowly takes shape around the outline of a nighttime city. I began by shooting the white noise from a television set, using the white level to determine how many dots you see on the screen. The higher the white level, the more frequent the dots. I bi-packed this matte into the optical printer with a shot of a New York cityscape. The television matte starts with a few dots and grows in density until the cityscape becomes visible.

After the creation of Software’s synthetic landscape, we move into Vortex (10 min 1972) which occupies and articulates that landscape. It is a frankly psychedelic film with synthetic improvisations of video feedback which obviously recall the sixties. It’s an extravagant light show that features one technique after another in a completely undisciplined fashion. It represents an aesthetic excess which mirrors a scientific excess. Psychedelia attempted to simulate some aspects of the nervous system that people were experiencing stoned. It exteriorized these states in multi-screen spectacles that allowed audiences to participate in a “sensorium.” Vortex is an electronic sensorium. Remember, in the sixties, the reconfiguration of space craft and atomic blasts into a colour and light show was an everyday expression. Everything was translated into a happening, and the stoned were processing everything in a very ecstatic way. The politics of that is a very mindless form of sensational experience — to sit and watch an A-bomb go off and say, “Wow, did you see the colours in that thing!” is a pretty reactionary thing to do. The film acknowledges that and lets the viewer proceed from that point, mindful that this moment has happened.

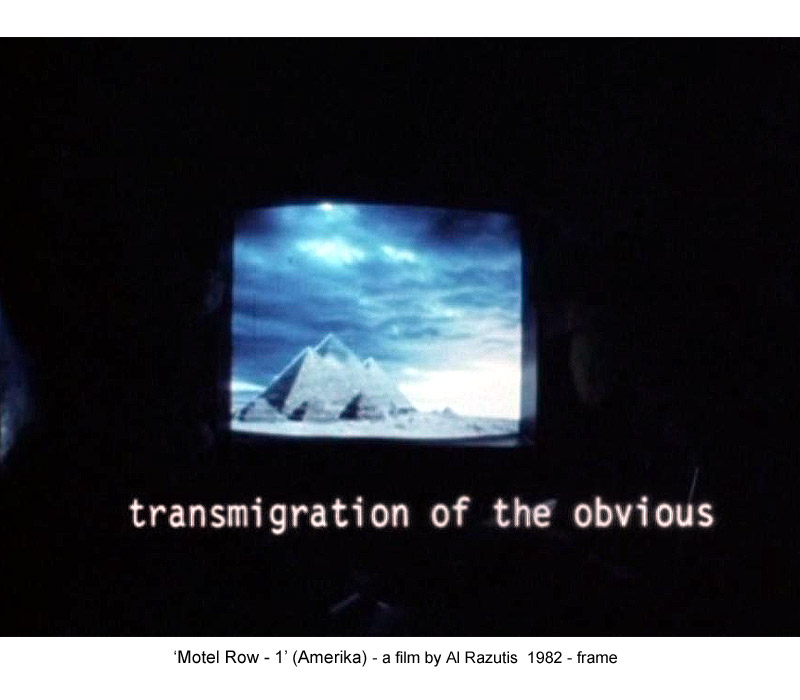

The next film is Atomic Gardening (5 min 1981), which operates in a very different register than the one which preceded it. After this film, it’s apparent that Amerika will progress through a collision of ideas and strategies. It’s a mosaic construction which is made up of seemingly incompatible elements. The soundtrack of Atomic Gardening is filled with military chatter — NORAD boys talking shop. It is lifted from a documentary which visits American missile sites. The image shows a series of time-lapse shots — circuit boards, with NASA stamped on them, immersed in a solution of chemicals out of which crystals are growing. These crystals looked to me like an expanding military virus, the virus in the machine, growing like simultaneous launch patterns. Meanwhile, the boys are talking about the two-key system, one to turn it on and the other to finish the sequence, and once the second key is turned, the missile is away. They run through a simulation and launch a missile as the end of the film whites out. This white screen burn-out reappears in a television set in an empty motel room. Three of Amerika’s films are called Motel Row because a motel is a temporary residence for the traveller, like so many of these films. In the first of these Motels (10 min 1981) I moved from the white screen of the television to a walk around an abandoned, graffiti-filled building with a wide angle lens. I wanted to establish the absence of the protagonist and a neglected, shattered landscape.

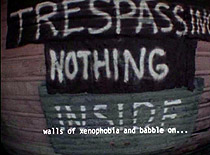

MH: The emphasis on the graffiti walls reinforces the gestures of the hand-held camera and the gestures of painting. Both marks are a contradiction in terms: anonymous signatures.

AR: The contradictory graffiti slogans are symptomatic of an American malaise. It’s a culture that assimilates contrasts by celebrating and then exhausting them. What I’m presenting is a cacophony of speaking subjects rendered anonymous through the act of graffiti — a superimposition of ideas, slogans, and clichés. It’s a wall of noise and political alienation. You put that together as a backdrop for an absent subject in a ruined landscape, and I think the viewer is cognizant of a growing emptiness, all juxtaposed with the fullness of the images we’ve seen earlier.

MH: It extends the absence of the human subject: the disembodied voices of Atomic Gardening, the techno universe of Vortex, the mushroom clouds of Cities of Eden. Motel Row brings us “back to earth,” away from the more stylized, technologically reprocessed imagery we’ve seen so far.

AR: The second part of Motel Row is entirely different. It combines three elements: a series of mausoleums, Hollywood soundtracks, and my own film Egypte. The mausoleums were shot in New York and Hollywood. It’s funny that all the East Coast graves are crammed together while the West Coast folk have manicured gardens separating everything; as in life, as in death. The corpses occupying these mausoleums are obviously on the opposite end of the economic/political spectrum from the anonymous graffiti people in the previous section. The Egyptians, as a culture, believed that the afterlife could only be acquired by rituals reserved for those who could afford the embalming process. So the Egyptians built these immense tombs called pyramids, just like the mausolems I show, which are similarly intended to convey the rich into the after life. Joining the two via montage implicates a mythology that rationalizes money and death. It suggests the metaphysical underpinnings of the ruling class — the Protestant ideal of material riches in one world, spiritual riches in the next. I joined the two by moving into the mausoleums until the screen blacked out, then moving out of the dark of the Egyptian pyramids, or by match cutting Egyptian hieroglyphics with graffiti. The hieroglyphics were a sacred language, so these cuts join the sacred and the profane. After we’ve laid the dead to rest, we see the first road movie in Amerika: 98.3 KHz: Bridge at Electrical Storm (5 min 1973).

MH: Bridge seems to recapitulates certain imaging strategies in Vortex, the constantly changing colours providing variations on a theme.

AR: But it’s a very measured structural movement. It was made one frame at a time, so I had a lot of control over the image. The storm is simulated through a variety of optical processes, which changed the colour and contrast of the image frame-by frame. The electronic processing is something that embellishes the movement rather than being the thing itself. In 1966, I shot a heap of super-8 footage driving all day over the San Francisco bridge. We drove from morning to night, and I wanted to release it as a forty-minute film with a radio soundtrack, but I’m glad I spared everyone that boredom. It was manipulated on the optical printer using a lot of bipacking. The introduction of video continues the movement of the image towards abstraction and a graphic extremism, an apocalypse and rapture. In 98.3 KHz: Bridge at Electrical Storm Pt. 2 I poured acid and hydroxide on the film itself to create bubbles and explosions, to attack the emulsion, then quickly washed and reprinted it before the image dissolved. So there were a number of procedures used to obliterate, alter, synthesize, and make the image fluid, rather than fix it in a documentary fashion. This was related to the sense I had of broadcast and electrical energy. I used to get up early in the morning and noticed that as the city started to come alive electrically I could feel it in the air, like some people hear AM radio in their dentures. We’re being inundated right now with broadcast information that’s flowing through us, so the transformation of the image was simply a way to make that concrete.

MH: Hence the electrical storm in the film’s title and its soundtrack, which features forty years of radio fragments. The bridge forms an enormous “X,” which doubles your own spray-painted signature that figures a number of times in the film.

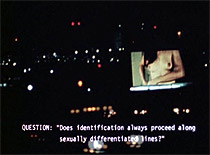

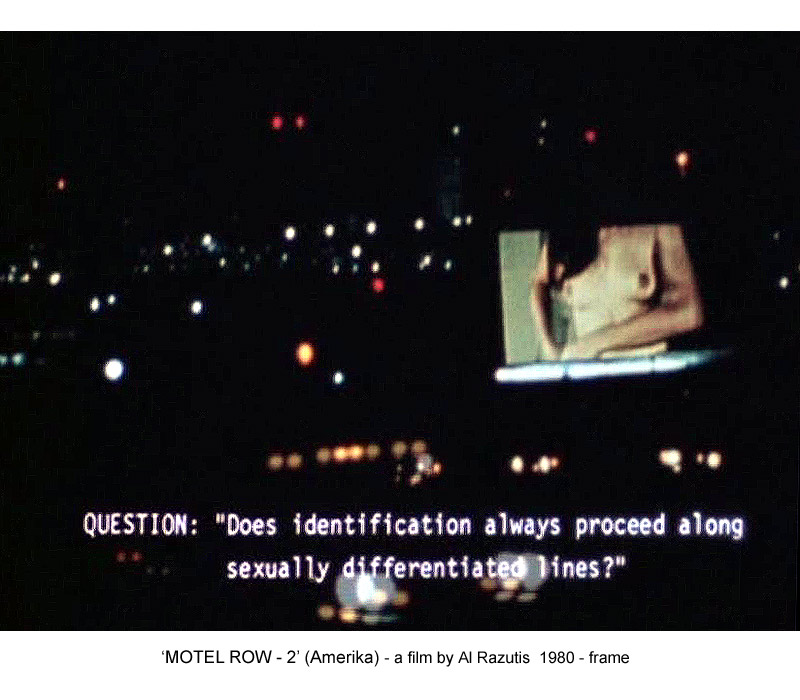

AR: It’s a fortunate coincidence. I tried to have my name legally changed to an “X” but was told I’d need to have a witness every time I signed a document. I wanted to have an institutionalized anonymity. The next piece is Motel Row Pt. 2 (8 min 1976). It’s a long tracking shot into Reno, Nevada. Now that you’ve done the bridge, here’s another car movie. And everybody’s wondering: where are we going? Are we going anywhere? [laughs] It shows a series of motel façades lit up at night, shot out a car window. One sign simply replaces the next in a long row of spectacle, because spectacle works to evacuate any depth of expression, any emotional attachment, anything that can’t announce itself on the surface. There are audio fragments coming in from various TV movies. The façades are intercut with a series of interiors which are basically empty except for television sets, where I matted in a number of found footage images: prehistoric women, male/female relations as perceived by Roger Corman, porno flicks. It shows the dichotomy of inside and out, glittering façades alienated from their abandoned interiors. This is followed by the first of a series of Refrains (1 min 1982) which punctuate the film. Each one is a static shot showing a dummy and a number of theoretical questions which appear as subtitles. These sequences came on the heels of my profound disenchantment with the academic community. The questions were pilfered from my old colleague Kaja Silverman, who could speak this language like no one else. She’d written up ten film studies questions which were part of a proposal for an avant-garde/film studies conference. So at various points in the film these questions arise in a pseudo attempt to theoretically assess the work. The questions are printed over a dummy animated on a turntable with jerky motions, and a fixed, smiling expression on his face. The backgrounds were done with a front screen and often replay parts of Amerika. The soundtracks are taken from canned radio plays from the forties or fifties which replay famous comic routines that refer to the question. So the bozo, the backgrounds, and the comic routines act to answer these preposterous film theory questions. The dummy faces the camera so he’s not really cognizant of the film material. One of the questions asks: Does sexual differentiation position the viewer?

MH: In other words: does it matter whether you’re a male or female?

AR: Behind the dummy, a screen shows an image of a woman taking off her bra, so it’s obvious that sexual differentiation does position the male (“voyeur”) and female (“looked at”) differently. On the soundtrack there’s a Marx Brothers skit, where they’re talking about marital breakdown and the incompatibility of men and women. So the question is negotiated in these three different ways simultaneously — through the Marx Brothers, the woman undoing her bra, and the dummy. I felt film theory was wreaking havoc with practice, that it was an arrogant and elitist enterprise and I wanted to lampoon it in these sections. The Refrain is followed by a film which used to be called Runway Queen. It’s a forties burlesque number showing a woman stripping, which is run through a video synthesizer to create echoes of her image all around her, multiplying her gestures. This sequence follows from the images of alienated sex in the motels and the alienated visions of women presented by the film. In the early days of video processing, men would take images of women and fuck them with technique. This scene makes the uses of these technologies explicit; these image technologies work to transform passive and inert figures, which are most commonly associated with women. It’s consistent with what music video has done to exploit the human figure. The narcissism involved in the portrayal of the singers is aestheticized and amplified with video special effects equipment. But in my case I don’t think anyone could take it as an erotic image at all. She’s dancing naked but dressed up with all these special effects.

MH: The echoes of the woman recalled the Busby Berkeley chorus lines where dancers shatter into echoes of the star.

AR: It’s a burlesque image from the forties with bumpity bumpity accompaniment. Its placement in relation to the fuck shots inside the motel rooms make it just another look at a displaced and alienated representation, like a floorshow in one of these hotels. And it continues to answer the question: “Does representation proceed along sexually differentiated lines?” Then Amerika hits the road again for The Wasteland and Other Stories (13 min 1976). In 1974, I approached the National Film Board with a film about Egypt. After they agreed to it, I conned the Board into letting me go down to Death Valley because it’s plenty hot there in August. I said I had to check out my equipment, my stock, and myself to see if I can handle the Sahara. They gave me some stock and I shot The Wasteland — it was my camera test. I mounted the camera inside the car with an intervalometer attached and drove from Vancouver to Las Vegas. The Wasteland is the torture test — some people find it very meditative, and for others it’s the beer break. The mounted camera maintains a fixed car hood and windshield position, while the intervalometer knocks out a frame every three or four seconds. This was then step-printed onto different stocks to destroy the pristine look of the original colour negative. The stepprinting that’s used here is 2:3. The first frame is repeated twice, the second three times, the third twice, the fourth three times and so on. Three frames is about the limit of perceptible change, and two frames is just below that threshold, so the strategy was one of exhausting the viewer. Rather than allowing the viewer to move in a perceptual flow, you get this staccato movement on an almost subliminal level. This drive arrives in Las Vegas at night, which initially appears as a string of abstract lights which become the nighttime façades of the city in a movement that’s very much like Software. After passing through an electrical storm, again created optically, we arrive in an insane roller coaster ride with intercut images of gambling and car crashes, video games and violence. Many of these images are related to vehicular destruction because the notion of traveling is a fiction — you’re not going anywhere. But the progression of my signs are not arbitrary; they organize themselves around the question of the male gaze. The male discourse is guided by machines: the fixed point of view of the car, the pornographic shot, the romanticism of the escape, the techno-fetishism of video effects, and what lies at the end of the road is destruction. But this amusement park of sensations only simulates these impulses, because your quarter runs out and the ride ends. So nothing’s changed. The idea of getting anywhere is hopeless.

MH: The Wasteland takes up the biblical themes that run throughout Amerika — begun in an opening title copped from Genesis, its constant evocations of The End, and its obsession with sexuality, which the Bible is quick to maintain within a genealogical progression that becomes equivalent to knowledge itself. But in your film these blood ties have been long abandoned, replaced by anonymous machine sex and pornography.

AR: Then the Refrain (4 min 1982) kicks in again asking: “Is identification the chief means by which a cinematic text structures its viewers?” Well, not in this film. [laughs] So I put the bozo in the driver seat pretending to drive, bewildered, with the backdrop of the casinos. The next question asks: “What does it mean for a viewer to distance him/herself from a film?” [laughs] Well, if you haven’t been distanced by this, I don’t know what’s going to distance you. Next question: “What is the relation between the viewer’s subjectivity and that conferred upon him/herself by the film?” With an image of a roller coaster ride. What is subjectivity? One long scream down the tracks.

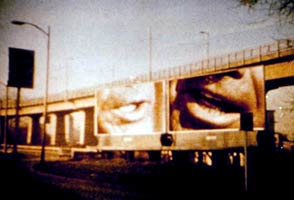

The second part of 98.3 KHz: Bridge at Electrical Storm (6 min 1973) follows. It brackets The Wasteland; it’s a kind of way in and way out. This is the last heavy-duty visual display in the film. But by this point in Amerika its visual opulence only reads as empty technique, part of an alienated sensibility that has moved men closer to their machines while ignoring everything else, everything but their own death perhaps. Bridge’s redundancy is underscored by having it played twice. The Wildwest Show (11 min 1980) follows. I shot a number of cityscapes, blacked out the billboards, and inserted pieces of found footage. So as we see cars passing through the streets, images of destruction are playing overhead in the billboards. The images, most of them violent, follow from a game show in which the contestants are asked whether what they’re watching is true or false: these atrocities, the war footage, the Vietnam protester going up in flames. The film conflates fiction and documentary footage, sometimes in appalling ways. In The Wildwest Show, none of the cars pay any attention to the images they’re passing, as horrific as they are. So images that would normally occupy our attention have become commonplace. I matted all of the images into billboards because I wanted to suggest the replacement of landscape with mediascape. It also extended my earlier practice of projecting into public spaces.

MH: There’s an accumulation of atrocities in the film — from the Second World War, Vietnam, old westerns. The effect of their rapid-fire progression is to level them out, to strip them of their historical and political contexts and regather them under some essentialist heading of Evil Humanity. While it’s clear your critique is aimed at North American media culture in general and television in particular, to what extent is your own film complicit with the practices it decries? The film includes some of the most extreme examples recorded of real people dying on film. Isn’t your act of deconstruction also complicit with the dehistoricizing process of television?

AR: The argument that The Wildwest Show sensationally obliterates the historical subject is exactly the point: that’s what the film is about. In order to illustrate my purpose, I’ve proceeded with such exaggeration and hyperbole that the viewer can’t feel sympathy for this process. It had to be presented as a case in the extreme. The viewer is confronted with the disparity between sound and picture, fiction and documentary. The film’s not proceeding as an analysis of these events and how they appear on television; it’s dealing with our awareness or non-awareness of this mediascape. Is it anymore moral to ignore this train of images, the daily atrocity of the news, for instance, or the late night movie? Mainstream media is constructed as a one-way communication system, and this was a way to talk back.

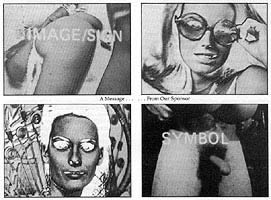

Halfway through this film it’s interrupted by A Message From Our Sponsor (9 min 1979) which reworks a series of commercials to show the rhetorical strategies at work. It concentrates on the sexual subtext of the beauty industry, its privileging of style and surface, all of which takes us back to pornography and the objectification of women. It came out of my collections of stock footage, in this instance, mostly commercials from the sixties. I began looking through them for patterns of organization, rhetorical strategies, and began a work which would deconstruct these practices. The film mimes commercial rhetoric in a way that makes it intelligible and explicit for the viewer. When The Wildwest Show returns, having been interrupted by this long commercial, the host says: “You’ve been a great audience. You’ve applauded just at the right time. You’ve laughed at the right time.” And now what do we do? We go on, right back into the destruction; it’s fucking relentless. Television is our coliseum. We used to watch Christians fed to the lions; today we can watch 40,000 kids starve to death every day, or the latest blood-letting in the Middle East. It trivializes morality or makes it impossible. And what are we doing about these images? Who is managing them and why? Well, after the Ontario Board of Censors banned Message, we knew who was managing the images. Obviously The Wildwest Show and Message are obscene films. But where is the obscenity? In the acts that were depicted? In their recording? Or their consuming? A Message From Our Sponsor was the first film I made in 1979. I optically printed the footage I wanted, cut the film together, added the semiotic intertitles, mixed the sound, and promptly forgot about it. I went on to finish For Artaud, Lumière’s Train, revised Ghost:Image, and made the Motel films for Amerika. Then the shit hit the fan for A Message From Our Sponsor. Canada’s National Gallery was putting together packages of avant-garde film, which were purchased and circulated, and Message was included. I was thrilled. Then suddenly I got a call saying the Censor Board had stepped in and that the Gallery had to remove this film from the package, otherwise the curator, Darcy Edgar, would be arrested. I said, “What! You’ve got to be joking.” It was the first I’d ever heard of the Ontario Board of Censors.

MH: So they couldn’t even show it in the National Gallery?

AR: That’s right. Darcy called in tears and said, “I’m in a no-win position. I want to show the work but I can’t, and how would you feel if we…” But you know me, I said “No fucking way is this film going to be cut or withdrawn; everything remains status quo.” I thought this would remain a local quarrel between the Board of Censors and the National Gallery. Then the Funnel, who were going to show the package, were also advised by the Board of Censors that if they showed the work they’d be arrested. So the Funnel withdrew from showing Message. Then I got a call from Susan Ditta at the Canadian Images Festival in Peterborough, who invited me to show a program of my work. I told her that I would bring Message, which others had been told they couldn’t show. She said she would talk to her board, and they gave it the okay. They were warned by the Censor Board not to show the film, and a couple of their board members resigned as a result — Anna Gronau and Ross McLaren, both from the Funnel. So we hit the screening and the place is jammed, people are hanging off the rafters. We start the films and there was this young projectionist there, and I said, “I don’t want you to have any problems tonight, so let me turn on the projector.” The whole time everyone’s waiting for the cops to show, and we had a big discussion about censorship afterwards. Two days later the Board of Censors charged everybody — the director of the festival, Susan Ditta; the director of the space I showed in, David Bierk; a member of the board, Ian McLachlin (who was the intellectual spearhead against censorship); and myself. Violation of the Theatres Act, they called it. We began with a freedom of expression, constitutional defence which was dismissed by the judge. Then the judge agreed that Amerika had to be seen in its entirety, that Message needed to be seen in context. What was notable in the proceedings was that Mary Brown, the head of the Censor Board, testified on the stand. She was completely dissected by the defence when she tried to explain the Censor Board’s basis which she termed “community standards,” but which turned out to be pretty vague. She also alluded to special considerations given “important” artists. The Crown offered a deal — you people plead guilty, and we’ll get you off on probation, and we told them to forget it. It tended to divide the film community between those who would deal with the Board and those who wouldn’t. I thought the Peterborough action had to come down, somebody had to get charged and go to court and show how ridiculous and dangerous these laws were and why they needed changing. It was important that the practice of the Board, their lies and contradictions, were exposed. One member of the Censor Board who opposed the film took the stand, and when he was asked what his background was, he said he’d been an usher in an Odeon Theatre. [laughs] It became apparent that the make-up of the Board wasn’t representative of a community, but of a position that was religious in its inspiration. After four or five days they dismissed the charges against me because they couldn’t prove I had anything to do with the screening in a direct way, which I found bizarre. They proceeded with the others, who were eventually convicted and fined $500. After Amerika was banned, a group of people came together to fight censorship in Ontario, called the Ontario Film and Video Appreciation Society. This group included Anna Gronau and David Poole, and they wanted to take Amerika to the Supreme Court and clear it, which they did. By that point Mary Brown was back-pedalling, figuring all this for bad publicity over stuff nobody sees anyways.

MH: It’s typical that you should run into censorship problems showing actors fucking in Message as opposed to the real people getting killed in The Wildwest Show.

AR: Both these films were made shortly after coming back to North America from Samoa, where I couldn’t help but be struck by the daily ferocity and excess of the media. If The Wildwest Show presents a series of questions which are finally about morality, I felt it was important to introduce the filmmaker to answer some of these charges. What follows is a film called Photo Spot/Terminal City Scapes (8 min 1983). It’s set up as a series of three phone calls to which the filmmaker responds. In the first of these exchanges the caller purports to be a fan of my work, in the second a curator, and in the third a psychiatrist. As a fan, he wants to glean technical information, which I deny him; as a curator, he wants to contextualize my work according to false historical paradigms; and as a psychiatrist, he says my work shows I’m psychotic, and he offers to psychoanalyze me. This all goes down on the soundtrack, and you hear only my voice on the phone. What you see is something else again. Each of the three calls begins with a set of technical diagrams that relate to scientific principles of perspective or colour saturation. And each set of diagrams is followed by an example of these principles, as if they were applied experiments. On the phone I talk about Amerika’s two orifices — Anaheim and Berlin, Disneyland and the Berlin Wall. The orifice is the place where you eat and excrete — culture comes in, products come out. I think there’s a connection with the fantasy city of Disneyland as a perceptual orifice that excretes fantasy on people and Berlin which is the barrier between the illusions of America and Russia. Here is the place where real terror, suffering, and death were institutionalized for decades.

Photo Spot is followed by a discussion between Samantha Hamerness and me about the continuation of the film. We’re arguing about the accessibility of Amerika and its political efficacy. Samantha argues that without a narrative anchor, the viewers are left adrift in a universe of signs that escape decoding by any but the already informed. In order to take apart dominant ideologies, does one assume their form or create another? And where does that leave the viewer? Samantha argues that for a viewer who isn’t aware that the media is predicated on sign systems, my film is largely incomprehensible, its effects relegated to a subliminal level. I reply that all images work on a subliminal level and that it’s a reasonable political tactic to be able to articulate the subliminal.

MH: But if most people can’t understand work on the level of the signifier, regardless of its message, is formal work, or even art, still politically viable?

AR: I’m not talking about reaching mass audiences; I’m talking about reaching an effective audience — work that’s impacting on the culture. If it doesn’t impact there, then it’s an elitist preoccupation between maker and mirror. If the work can inspire some people or unpack different points of view, that’s enough. Fifteen years ago, I toured a show of holography across Canada and I met up recently with a woman from Hamilton who saw that show and was moved to make holographic work of her own, a practice she still continues.

MH: The auto-critique discussion between Samantha and you that opens Amerika’s third reel – what conclusions do you reach?

AR: Acknowledging that the subliminal is too narrow a political arena, Amerika shifts strategies. The last hour features less image manipulation, a more direct political engagement, and an evocation of several mainstream genres: the musical, the chase scene, the psycho thriller. It begins a narrative of sorts — a musical set to the Velvet Underground’s “Black Angel’s Death Song.” The film is called Exiles (11 min 1983) and it’s a kind of boy-doesn’t-meet-girl story. It’s shot in two separate locations and both spraypaint signs and slogans on a number of ruined walls. I like this section. It’s very restful after all the hard stuff that precedes it; we can just sit back and watch a couple of people write stuff on walls. Formally, I joined the two by a number of flare outs. I took a 400-foot roll of film and flared it in the darkroom and cut it on the Broll so the image continually goes to white. This eradication of the image echoes the nihilistic iconoclasm in the film. What follows is the longest film in Amerika called The Lonesome Death of Leroy Brown (28 min 1983). The first of its two parts shows Amerika’s final road trip — cityscapes across North America shot from a moving car. The film cuts between shots that move left and shots moving right, moving closer to its subject until it arrives at a woman who is stalked into a vacant lot where she draws out a gun and shoots at the camera.

MH: Why is she being followed?

AR: Because we’re still not finished with the issue of the representation of women in cinema and I wanted to give it a simple reading. This is about as simple as it gets — voyeurism on a basic level. Male gaze equals violence. Like all of the films in Amerika’s last hour, Leroy Brown takes off from the discussion that Samantha and I had. Samantha says that what this film needs are more literal stratagems of identification, so I’m capitulating to the argument. The formal techniques haven’t worked, so I’m giving you the pop version, complete with chase scene and guns. This is followed by a long interior scene where I’m sitting in a chair with a stretch of pantyhose over my face, drinking beer, smoking, watching TV, and pointing guns around the room. It’s a real send up of psycho thrillers — all set in a motel room. The TV is playing out a documentary loop of a black guy getting blown away by the cops. The radio is playing Jimmy Swaggart talking about hell, damnation, and all the shit that’s going to befall you. So this room is a meeting of two worlds of violence — moral, religious violence, and authoritarian police violence. I called it the “lonesome” death of Leroy Brown because the black man’s death on television is one which occurs anonymously, without history or context. In the end, I turn my gun on the camera and shoot out a Plexiglas screen set up in front of it. At a screening in Vancouver a lot of people were upset about this, claiming that I was directing my aggression against the viewer. I said, sure, I’m shooting out the field of view. We’ve experienced brutalizations of a secondary nature when we’re watching images, but this leads on to the point of view itself getting shot out.

MH: It’s as if the camera itself is to blame for images that can only lead to estrangement, alienation, bad sex and violent imaginations.

AR: The film has delivered the viewer to a number of excesses. It has attempted to show how meaning is fabricated, and attempted to implicate itself as a film working, at least in part, within this system of signs. It has demonstrated that the filmmaker/author is capable of lying at any time.

MH: If Amerika’s first hour has demonstrated the visionary wonder of sixties filmmaking, its second leads on to an examination of signs and surfaces — Las Vegas fronts and television — and its structural strategies are in keeping with the seventies. This hour closes with the enigmatic Photo Spot, a film which reaffirms the filmmaker as an isolated technician, working out problems in the paranoid seclusion of his studio. Amerika’s third hour begins the task of reconstructing a social order — raising questions of engagement and accountability which are at once personal and political. This social order is staged in a number of narrative fragments which are no less brutal than some of the borrowed media fragments which have preceded it. It’s filled with ruined buildings, smashed television sets and attempted murders. It also makes explicit a theme which grows in importance as the film progresses, namely, a male-female dynamic which insistently returns to the question: what is a women’s place in patriarchy? The answer: brutalization, neglect, abuse, or answering the violence of their environment with a violence of their own.

AR: It parodies the male discourse by taking on the film theory fave notion that the male gaze is perverse — it fetishizes, disavows, and fears castration. You’ve got this played out to its logical extreme. By the film’s end the male has become a drunken terrorist, repeatedly consuming images of violence and responding by shooting out the camera. His attitude to women: we’ll either fuck you or kill you. If we can’t control you, we’ll murder. To control we’ll use everything we’ve got: media, pornography, fashion, glamour, money, the works. Males have been controlling the production, sexualization, and dissemination of images, and this is the process that Amerika explores. The technological fetishization of the image in the first hour deals with astronauts, cars, wars, and atomic bombs, all aestheticized in a romantic, universalist fashion. But then it turns to an examination of the media itself in terms of gender representation. Then things get ugly. And stay there. As far as my work is concerned, there is an early interest in pop-culture and political agitation in the late sixties, non-Oriental mysticism (alchemy) in the early seventies, openly political and anarchist stratagems in the late seventies and early eighties, with a heightened dedication to political avant-garde practice in the current phase. I think it’s important to see avant-garde film generally as occupying a relationship to the era and culture within which it exists, and that each form of the “avant-garde” is but a moment in a larger process of perceptual change and perpetual revolution which derives its legitimacy from engagement rather than fixity and essential qualities. I use the term “avant-garde” instead of “experimental” because I think it better identifies the kind of cinema that I refer to (the political, the transformational, the artistic, and those historically linked to the other avant-gardes); I don’t believe it is “dead” or has outlived its usefulness in shaking up the status quo. If ever there were a time when shaking up is necessary, it is now, in the age of mass communication, mass propaganda, mass conformist lifestyles, an age that is dangerously close to a holocaust. An art for this age is an art that responds, in part or in total, to these world-wide issues or is at least conscious of the context. “Experimental,” to me, connotes apolitical isolation.

As I perceive it, the choices facing most are: pass the toilet paper and sit in your cubicle until the sewer system plugs up (that is, until the next academic conference). Get used to the smell of it all and maybe soon you’ll develop an appetite for shit (symbolism, obfuscation, the flag, name-dropping, experimental film ghettos, travel grants to safe [sponsored] exhibition houses, mention in sponsored/subsidized publications). Become a clever plagiarist; make your work in a “theoretically informed manner” (don’t forget the flag); act non-committal in all political issues, and as soon as regionalism, censorship, or any number of causes arise, make sure your work is included (along with an appropriate quote by you). Or… finally free yourself of this and all kinds of bullshit and be unconcerned whether you fit one school of thought or another, whether your films are “modern” or “post-modern,” Canadian, Kanadian, or international. Free yourself from determinations and the obligation to identify your inspiration as being the tundra, factories, television, people, and/or “Michael Snow.” And free yourself from intimidation by scribblers and quasi-theorists (they’re looking for a warm place to shit, you need not worry). Free yourself from the notion that history and theory will exclude you. And then you can discover your own praxis and that creative imagination which is not celebrated in the cancer ward of suffering romanticism.

Al Razutis Filmography

2 X 2 17 min 1967

Inauguration 17 min 1968

Sircus Show Fyre 7 min 1968

Poem: Elegy for Rose 4 min 1968

Black Angel Flag … Eat 17 min silent 1968

Aaeon 30 min 1971

Le Voyage 8 min 1973

Visual Alchemy 8 min 1973

Fyreworks 1.5 min 1973

The Moon at Evernight 9 min 1974

Aurora 4 min 1974

Watercolour/Abstract 6 min 1974

Synchronicity 11 min 1974

Portrait 8 min 1976

Excerpts from Ms. The Beast 20 min 1971-81

Visual Essays: Origins of Film 68 min 1973–84

Lumière’s Train (Arriving at the Station) 9 min b/w 1979

Méliès Catalogue 9 min silent 1973

Sequels in Transfigured Time 12 min silent 1976

Ghost:Image 12 min b/w silent 1976–79

For Artaud 10 min 1982

Storming the Winter Palace 16 min b/w 1984

Amerika 160 min 1972–1983

Reel 1 50 min

The Cities of Eden 7 min 1976

Software/Head Title 2.5 min 1972

Vortex 10 min 1972

Atomic Gardening 5 min 1981

Motel Row Pt. 1 10 min 1981

Refrain 1 min 1982

98.3 KHz: Bridge at Electrical Storm 5 min 1973

Motel Row Pt. 2 9 min 1976

Reel 2 53 min

The Wasteland and Other Stories 13 min 1976

Refrain 4 min 1982

Motel Row Pt. 3 2 min 1981

98.3 KHz: Bridge at Electrical Storm Pt. 2 6 min 1973

The Wildwest Show 11 min 1980

A Message From Our Sponsor 9 min 1979

Photo Spot/Terminal City Scapes 8 min 1983

Reel 3 57 min

Refrain 3 min 1982

Exiles 11 min 1983

The Lonesome Death of Leroy Brown 28 min 1983

Fin 8 min 1983

O Kanada 5 min 1982

Closing Credits 2 min 1983

On the Autonomy of Art in Bourgeois Society… or Splice by Doug Chomyn, Scott Haynes and Al Razutis 23 min 1986

The Films of Al Razutis

Al Razutis is a Canadian iconoclast, an artist who was instrumental in the formation of two west coast film distributors, a short lived union of Canadian film artists, a production co-op, separate magazines on fringe film and holography and a much publicized battle with Ontario’s board of film censors. Along the way he taught media production at the Banff School of Fine Arts, the Vancouver School of Art, Evergreen State College and Vancouver’s Simon Fraser University for a dozen years. He has completed some forty odd films and videos alongside various performances, paintings, holograms and intermedia productions. While he has worked hard over the years to secure an institutional base for all aspects of fringe cinema, he is better remembered for his anti-institutional stances. Over and over he has published angry missives against the press, government, art bureaucrats and other artists – decrying in unflinching language the (perceived) abuses of power and privilege. A self-appointed moral standard bearer, Razutis has done much to politicize and galvanize the possibilities of a Canadian avant-garde.

Born in Germany in 1946, Razutis studied chemistry and physics at California Western University and did post-graduate work at the University of California, Davis. After dropping out of university he began screening and producing avant garde films in 1967. Shortly afterwards he moved to Vancouver and ran film shows at the Intermedia Artists Co-operative. Razutis’ earliest film work is 2 X 2 (17 min 1967) – a double-screen confabulation whose original elements were sold and subsequently lost. Taking parts of this film, Razutis later made a single-screen version entitled Inauguration. A frank celebration of 60s counterculture, it reveals a domestic interlude of communal consciousness, transported from the commonplace through good drugs and collage. Awash in a luxuriant sensuality and informed by Jung’s archetypal symbology, Inauguration simulates the drug state with a multilayered superimposition driven by an electronically processed version of Velvet Underground’s Heroin. It shows day trippers woven into pictures of an upset social order – riot police and marchers, soldiers and martialling arms in foreign lands – as the counterculture trappings of drugs, sex and music join their anti-authoritarian counterparts on the street. Later, Inauguration, fragments of 2 X 2, and additional footage were collaged together to make 1967-1969. The new film is a sixties time capsule that draws together images of war and pornography as a reflection on a social order gone wrong. It pits the administration of consent against a hedonistic and personal despair, its drug-addled protagonists lost in a sensorium of fleeting impressions. Cast on two screens set inside a single frame, 1967-1969‘s binary oppositions energetically replay the personal/political dynamics of a society in upheaval.

Sircus Show Fyre (7 minutes 1968) is a hypnagogic circus trip – reinventing three-ring conventions according to a childhood imagination. Forced to photograph from ringside, Razutis lends a gestural cadence to his subject, adding layers of superimposition, freeze frames and dissolves through rephotography. His project is a romantic one – the redemption of a childhood vision covered over in subsequent years with an education that destroys this early and innocent sensory revelation through naming and the habits of vision. Sircus embraces this romantic ideology, reshaping the circus according to a childhood calling, reinventing vision in a quest for primary consciousness.

Poem: Elegy for Rose (4 minutes 1968) concerns an American sex worker (Rose), photographed at night in a blurry cluster of tenements and high rises. Razutis scrawls a black marker poem over the image, though it can only be read by taking the film out of the projector and examining it by hand. Twenty years ago the filmmaker described it as “filmically, glimpses into the world of a hooker (filmed in s.f. chinatown) and streams of hieroglyph intestinal words – the poem written transversely across the film — lines forming words disintegrating ink textures sometimes recognizable and the intrinsic rhythm of strain-thought. Text: metaphorical poem (which can only be read by TOUCHING the film and READING words on celluloid tape transversely) and it is an elegy for Rose: streetwalker… sound six layers of electronic music and sound poems (the poem read) amidst eerie insanity of a child’s laughter assassinated by lies.” Poem is a kind of anti-film, serving notice of film’s double status – as an object in the act of its making and handling, and as a process in the act of projection. The words pass through the projector gate like strangers past a car window – and Razutis insists that if we hope to find out more about our subject, we have to get out of the car. The artist’s cinematic scribbling replaces the voyeurism of film with a personal notation, drawing the viewer away from the body of the audience in order to engage experiences that can only be understood alone.

Black Angel Flag … Eat (17 minutes silent 1968) is a film which begins with a long stretch of darkness inside which pictures occasionally appear. They alternately show a woman walking through a set undergoing construction, and television excerpts. Audience upsets led the filmmaker to destroy the film.

The collapse of Intermedia sent Razutis into a wandering tail-spin. He had begun regular avant movie screenings there, and there was a modest equipment cache and a budding distribution effort. For two years he scrambled to pay the rent until a job offer arrived out of the blue from Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington. Evergreen had a vast array of new colour video processing facilities, far outstripping the black and white possibilities which remained the cutting edge in Vancouver’s video scene. Working with a feverish intensity, he produced half a dozen film/video hybrids which he claimed would visualize the inner workings of the mind. These films include Aurora, Watercolour/Abstract, Synchronicity, Software, Vortex, Aaeon and Fyreworks. Each of these six films began with film imagery which was transferred to tape, manipulated using a video synthesizer or optical printer, then transferred back to film.

Vortex (12 minutes 1973) enacts a virtuosic display of electronic effects and video synthesis which draws together a starry outer space world with the interior space of the machine. Founded on a succession of collapsing symmetries, the screen doubles and breaks insistently, misshapen heaps of colour turning as if in recoil from its likeness across the dividing line of this fearful symmetry. Twisting in a continual flux of engorged psychedelia, this unfolding phantasmagoria of multi-coloured spectacles is set to an electronic wash of pulsing modes and synthesizer jargon.

Aurora (4 minutes 1974) is a study in blue and orange. Begun with the quietly ebbing strains of a blue tear, a succession of fades pass these cool droplets from stage right to left. These blue remarks take on a prismatic edge before introducing an orange ground behind, simmering, as if it were the source of the image, the sun of this two-headed constellation. Blue shades drift across the screen’s surface, gathering in a slow swell that fills the frame, turning it into a blue sigh that slowly undulates before parting again to reveal its origins in fire.