Notes on the invisible: Caspar Stracke’s Doppel

“Subtly, subtly, they become invisible; wondrously, wondrously, they become soundless—they are thus able to be their enemies’ Fates.” Sun Tzu, The Art of War

When I’m inside my house I don’t see it. Like my body, the way my cells repair and replace. It’s happening all the time so I never give it a thought. My favourite falafel place, the vegetable shop and cheese store have all vanished. Though it’s true, for instance, that many years ago I had to be trained to use an object as simple as the toilet, now I use it everyday without ever noticing (except in its absence). Once I can grant objects a name, I no longer have to experience them. This gives me more pleasure than it should. What I think of as novelty or invention consists exactly in this act of naming. Table, window, grief, love. I live in an invisible city.

In my city there are places for eating and places for looking: the cinema, the museum and art gallery. I schedule my looking, I set aside the hours in my daytimer, like everyone else. Inside the gallery, looking is always looking again, this time through an artist’s eyes. I leave my looking to experts (the army of news gathering professionals, the bevy of artists fine tuning attentions). Artists make the familiar strange and the strange familiar, reminding me that this double vision is also work. The eye sweats, reddens and closes with fatigue. I am only interested in their highlight reels however. I skim the cream of their insights, then forget all about it and move on.

Caspar Stracke sends me travel pictures of buildings that are visible only to those who don’t see them every day. At first they don’t seem like that at all, these monuments, they appear like the supermodels of buildings (Look at me! At me!) but that’s only because I’ve never seen them before. Naming is the best way to leave memory behind, and after that, pictures. I am grateful for these pictures, knowing they will help me in the task assigned to me as a citizen, to forget as much as possible. I constantly seek out new movies and friends so that I can sharpen my practice. Of course, nearly everything around me is busy with the work of erasing (what is velocity, and the time machines of the home computer and automobile, but conveyances of forgetting?), but there are infinite kinds of forgetting, some offering very special pleasures. Because Caspar is a friend, he knows better than most what experiences will give me the most delight in forgetting them. I treasure his pictures, I relish them, though in six months, if you should ask, I would claim perfect innocence of their existence, and I’d be telling the truth. Marriages have been built on fainter exchanges.

The pictures arrive in a link. Our mails are threaded and linked in momentary thoughts and neural spasms too quickly consigned to that withering of language known as e-mail. I open the link and a collection of pictures, small and crisp and shining with digital health look back, evidence of his recent globe-spanning ventures. Somehow, he manages to arrive before leaving. But wait. Every building is doubled and copied: is this the international style? The Peter’s Dome also appears in the Ivory Coast, the Washington Mall Dome rises again in the millionaire manse of Li Qinfu in Ping Hu. The Parthenon reappears in Nashville. Three case studies, like the three dots that make up an ellipsis… And so on. Etcetera. They are particular examples, sure, but also evidence of a trend, or at least, a tendency. They are presented on either side of the image, the shared architectures joined together to provide a smooth backdrop for their inhabitants. The artist, the professional looker, has made one world out of two. What I am witness to is a visual esperanto (once named desperanto), a postmodern Babel where the fraternity of human kind (“erased like a face drawn in the sand”) may find common frames to grow old in. Does this double vision relieve differences or accentuate them?

I am reminded of aerial reconnaissance photographs taken during the Second World War by Allied bombers. Month after month they would be gathered, the same missions flown in order to expose the same pictures, which were laid one on top of another at intelligence headquarters. All the common points of these maps would blend and become invisible, but any new structures were immediately apparent. These differences were analyzed and interpreted before the important decision was struck: destroy it or not? Though Allied Forces proved themselves eminently capable of protracted and criminal bombing campaigns in Germany and Japan, strategic interests (“intelligence”) required the foreplay of reproduction.

Find the difference in these pictures. In North America, post-war newspapers carried split-screen pictures of paired domestic scenes, seeming almost alike, though subtle changes appear in one image (the handle of a drawer missing, an empty glass) which required identification. The schooling of difference, the look as target practice. The caption beneath the second picture: what has changed?

In Caspar’s pictures I am presented with only one side of the story, each building has been cleaved in half and knit together with its dreamed double, its twin, which stands in a setting entirely distinct from its original. Pinh Hu is not Washington, D.C., though southern Washington, with its epidemics of teen pregnancies and crack, its gutted educational system and systemic poverty is far from the cameras which train global eyes towards the symbols of state on the other side of the river. Even Washington is not like Washington.

The artist has made a cut, years of training develops his instrument which extracts some moment of the world (a note, a collection of words) in order to rearrange and represent. My eye is drawn to this cleavage, the way the two domes knit together, and the more seamlessly the artist does it, the more his own gesture is emphasized until it too becomes invisible. My eye runs over the cut, and then it forgets, moving onto the foreground, where residents (the cast) and casual passersby loom in the shadows, frozen in a moment of impossible distance from the circle of their own lives, and that other life, which calls them from across the divide, the unseen world which they might sense only as a nagging duty. What did I have to do again? This moment is one that will almost certainly be unremembered, especially for those tourists gathered to make pictures as evidence of their travel (they were never there, so what is there to remember?).

Two sides to every story, and two architectures. But when I look to find any of the cast doubled I see only a singularity of forgetting. They appear so different, the Ivory Coast workers, the strollers and reverents in Rome. They are part of the cut, but because they live on either side of it, tragically incapable of removing themselves from the picture (like me, like all of us) they are condemned to the company of their own thoughts.

My laptop (the digital groin, the primal scene, no longer forbidden, but necessary and compulsive) remaps the world according to the cut. The distance between one thought and another, your blog and mine, is rendered as quickly as a tap of the fingers. Oh, there you are! I lose my body and memory (what if computers smelled?) but not my cut. It’s the greeting I have left. It used to belong to him, to the artist, but he shares his yields, and now it’s mine. It’s the way we have to talk to one another. Foreign architectures say hello through their familiar appearance. It’s a beginning, and sometimes beginnings are enough.

In an earlier work Stracke also takes aim at architecture. No Damage (13 minutes 2002) reconvenes New York City as a picture playground strained through the digital poetry of his laptop. Dense montage bursts from an array of movie spectaculars, educational adventures and tourist flicks, show a manufactured city which rises (in hope and aspiration) and falls (back to the drawing board). Partial dissolves, audio glitches, picture bumps, scratches and mismatched colour schemes underscore a new ideal of beauty. In this glitch city, hard-boiled noir detectives become gay cruisers looking for anonymous pleasures in the men’s room. Women are figured as modern dance accompaniment to immigrant labour, or the haunting, cosmopolitan Busby Berkely face which laconically smokes while turning into a city. (My city, my mother, the place I came from. They will bury me here.)

In the closing movements of No Damage, New York is ripped apart, torched and flooded (once again the rise and fall). The distance afforded by the world as picture (Praise be to Allah) can tear holes in these landmarks in the months following “9-11.” (No, not the overthrow of the Chilean government by CIA-sponsored fascists, the other 9-11, broadcast live). Caspar, how could you? Caspar, how could they? The city grown too familiar to me as an image, is also familiar to others, whose lives are similarly reflected in the twin towers, but in ways I could never imagine. The terrorism of pictures. The return of the look, the empire struck back, the digital consensus and global village brought home.

No Damage and Doppel have this in common: the background is foreground, the setting is the subject. The artist pulls focus in order to reveal the environment as a product of will and imagination. Of power. One building is already two, my neighborhood already doubled and shunted across the globe. It is no accident, perhaps, that these doubled architectures should occur to a New Yorker. They martial a grieving momentum from the catastrophe of the twin towers, those capital monuments which rose in answer to one another, call and response, office space and residence, but also irresistible image, subject to terrorist attack twice in the course of a decade. Two towers, two planes.

Stracke’s twinned architectures are not a lament for the manifest destiny of empire brought low, but a demonstration of how invisible power (whiteness, for example) is reproduced and returns in order to make the original visible again. I remember the girl in Vera Cruz who marveled at the miracle of my white skin. Not Orientalism but Occidentalism. The bodies leaping from the collapsing towers were pictures forbidden by the networks. No, this is too much to bear. Innocent bodies (Aren’t they? They didn’t put a gun to anyone’s head, did they?) falling to death in panic and fear, (it could have been me), the clash of civilizations. There is warfare in the global village: cries to prayer and airplanes lifting off. Only this time it was not our pilots (God speed), armed with liberation theology and Agent Orange, entrusted with the secret bombing of Cambodia, or the invasions of Haiti, Grenada, the Philippines… (and so on).

Television has thrived on images of imperial ventures, but it was rare (unpatriotic) to share airtime with the North Vietnamese (an apartheid of representation: no Cubans or Columbians or). Ask Michael Moore a question about Iraq and he’ll show you a heartbreaker from Flint. Globalization has often meant Americanization, not ‘have’ versus ‘have-not’ nations, but the poor subsidizing the rich. Stracke’s double vision (double bind?) reminds us that globalization cuts both ways, that there are twin towers or at least twinned monuments spread across the globe.

On the other side of the familiar, the invisible, the street I walk across every day, is another street, which appears exactly the same. I am headed there now, so that I can see for the first time what I see every day. Forgive me for hoping that there is not another one in search, equally curious, equally indifferent, approaching from the other side. Wearing my face. How would I recognize him?

Check it out on Caspar’s site: www.videokasbah.net/doppel.html

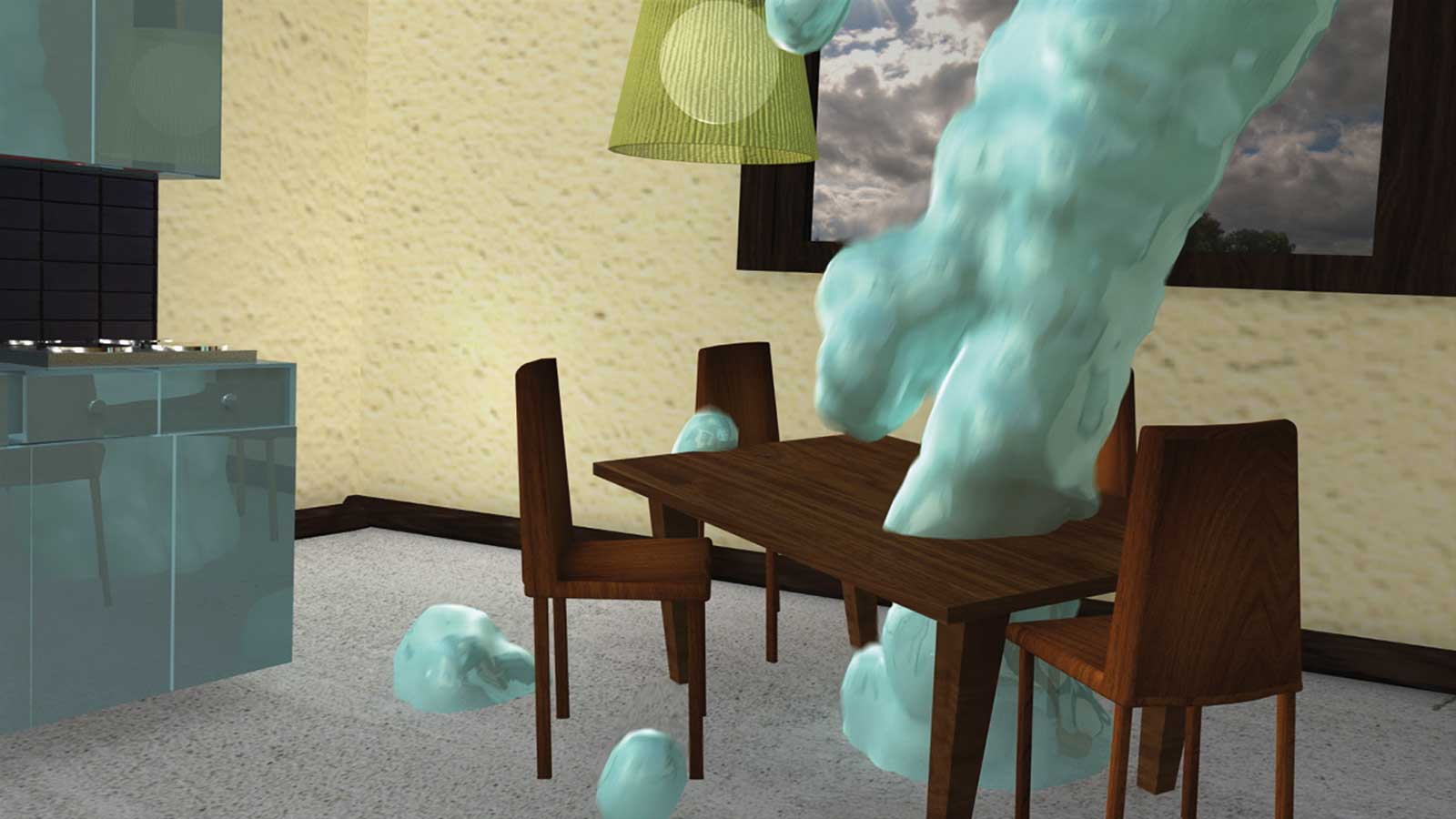

time/OUT OF JOINT by Caspar Stracke 85 minutes 2015

A maximalist freefall into the world of time reversal via science and art. Stracke’s delirious visual inventions propel this cross-cutting essay doc that replays backwards birthing, the supposedly Satanic verses from backwards Led Zep records, and Japan’s famous Tsukiji fish market. Twelve years in the making, the artist brings his roots as an experimental filmmaker fully into the digital realm, producing inventive and playful procedures for information processing. His musical inclinations are everywhere present, this is a movie that is composed and de-composed, sliding between hi-tech science labs and countryside ruminations on mortality with an internationalist’s ease.

The subject of time is particularly well suited to the film medium, where time is an essential and plastic element, it can be stretched or compressed, and reaching deep into his experimentalist’s trick bag, the artist offers us astonishing views of city streets rolling backwards, or unbirths, or hypnagogic forests. These alternate with performative turns where a street hawker sells his ability to say anything backwards, or scientists geek out on light demos, or else the movie maker himself tosses his weighty time books into a stream, and then follows them into the drink like a modern day Chaplin.

“Is it actually possible to have time go backwards? See for yourself with a film that Martin Heidegger and Gyro Gearloose could have made together.” (cph dox) The global all-star cast includes punk super 8 icon turned philosopher Manuel DeLanda, Marxist philosopher Agnes Heller, experimental filmmakers Alexander Galeta and Narcisa Hirsch, BioTime researcher Michael West, atomic physicist Mikhail Lukin (Harvard), bioenterologist Aubrey DeGrey (Cambridge), biologist Stephen Spindler, particle researcher John D. Cramer and NY choreographer Sara Rudner.