Richard Kerr: The Last Days of Living (an interview) (2000)

Richard Kerr is the most patient of cowboys, venturing into the no-zones of North America to corral rare pictures. His filmmaking invariably finds him driving with his seeing machines in tow, looking for that moment when the road will steer him towards an earned coincidence. His eyes are trained always on the myths of masculinity, stopping to examine baseball stadiums and truck stops, loading docks and military bases. But far from celebrating a cinema of testosterone, Kerr obsessively returns to places where duels have been fought and lost long ago. There are no bloody hands here, only the corpse of geographies that bear the scars of forgotten ideals. Far from the teeming crowds of the metropolis, he waits, patiently, in order to turn cities into deserts, shipyards into funeral homes. Uninterested in whodunit story telling, he chooses instead to show the wounds of our stories, the places that remain after sunset swoons and happily-ever-afters.

RK: In the eight years I’ve taught at Sheridan College and the University of Regina, I’ve had maybe five hundred students. Not one comes to mind who is still making their own work. Lots of them come out of the gate with interesting ideas and stop. It’s hard. You don’t have financial support but you’ve got to pay the same price as the mainstream guy. And there’s no revenue for your product in the end. If you’re making dramas, you get paid twice — once to make the work and once to sell it. But if you’re making art, you do your own distribution, and the hustle is hard. There are no easy nights out. Do you really want to leave the kids after dinner and head for a screening where someone’s going to give you a rough time? There’s only one return — you get to make another film. We’re fortunate in this country to have government funding; you step up to the plate and the money’s already there. We can choose where we want to work in the system. Do we want to get money from the provincial arts board, the university, Canada Council, Telefilm, DOC…? There are many doors you can knock on to find money. But almost all favour mainstream dramatic work and are geared to take you up to bigger and bigger budgets. There’s never been a real home for the R&D filmmakers in this country — I’m talking about the documentary filmmakers in Quebec and the experimental folks in English Canada. There’s never been a place where these people could go and just make work. Why not a Studio X at the National Film Board? What would it cost for the Board to put up two or three filmmakers a year — pay them a decent wage and waive their lab costs?

MH: The Canada Council is an organization that dispenses money to artists, including fringe filmmakers, and to the organizations that support them. Some would argue that if it was eliminated, it would mean the end of Canadian art. Do you feel the Council is oriented toward the production of feature-length dramas?

RK: They’ve changed with the demand of the market. But I’ve yet to have an experience up there where a serious experimental work has been turned down. They support experimental film, no question. That doesn’t mean it gets the most money. In this country there are only a dozen experimental filmmakers who’ve been making work their own way for more than a decade. Canada Council will never exist forjust one kind of filmmaking. And I’m not so sure that in a utopian world people would make experimental film, even if the money was there. I don’t know that people want to work alone like an experimentalist does.

MH: Is there anyone making avant-garde film today?

RK: I think of it as historical periods, not something I’m a part of. If I were a sports fan it would be like the original six in the National Hockey League. There was a period of time when it was contained, the facts were in, there was measurement. When Snow was making Wavelength in New York, that was an avant-garde period. I just hope that people working now can go on, and it’s all right if the work isn’t so new. Sometimes you have to go back and relearn an old stroke. That isn’t the way I used to think. I used to feel that the next work had to be bigger and more complex.

MH: Tell me about the beginning.

RK: I quit playing sports and was looking for something to replace it. I always had my own business in the summer — a furniture company that needed pictures of the merchandise. I got myself an old camera and sat down with a stack of Popular Photography magazines and taught myself how to develop pictures. I had dropped out of first-year high school to play hockey and was wandering around Conestoga College when I saw these hippie-types with film cans under their arms. I said to myself, I want one of those, I want to make a movie. There was something about how big it was in that small container. Big emotions in a small can. Little did I know. So I showed up at Sheridan College with a borrowed portfolio and next thing I know Roger Anderson is scraping emulsion off film, and Jeff Paull is projecting images on garbage bags and the world changed. It was the only time I experienced a hierarchy where the people who made experimental films were at the top. A lot of good people came out of that school — Phil Hoffman, Steve Sanguedolce, Gary Popovich, Carl Brown, Louise Lebeau. If you were doing your own thing, people recognized you for that. No cops and robbers in this group. We were told to make a film about ourselves first before turning these powerful tools on the rest of the world. I was never one for making directly autobiographical work, so I made a film about something I was very close to at the time — the Amish community in Kingston. That became Hawkesville to Wallenstein (6 min b/w 1977).

MH: At one point the camera passes over a sign that reads “Welcome to Eternity,” and as we watch these people working it’s as if life would never change. Because they look the same as they did a century ago. They appear like a living photograph.

RK: It’s a documentary. If I had had more money I would have put talking heads in it; that was the kind of making I was involved with. Hawkesville set up the template for all my work, where I start at a distance and get closer both physically and psychologically. I haven’t changed my way of working since then. I showed the film to Don Haig at Film Arts, the distributor, and he came back with a box of film — 1000 feet of negative. It was a pretty big deal for a second year film student to go into Film Arts and hustle a box of film. He said go shoot the same thing in neg and in colour. Take it down to PFA and get it processed and when you’ve run out come back and I’ll give you some more. So I went out one weekend and shot the same thing in the fall and realized I didn’t want to do this. It was too easy. That was a key moment. So I returned the film to him and thanked him and realized I wasn’t destined to have a business card that year.

MH: You still feel very close to your first two films.

RK: They say more about me as a filmmaker than any of the others. They share an observational documentary sense, a rhythm in the images; what Brakhage would call the “moving visual thinking element” is pretty consistent. Why do we need to try all these different styles and genres? I think that’s natural when you’re developing your muse but not when you’ve hit the time of your maturity. It takes a while to get there, though — ten, twenty years, just like a writer or poet.

MH: What do you mean by developing your muse?

RK: What you’re saying and how you’re saying it. How you’re relating to the world as you get older. I’m not overly prolific. I make something every couple of years. I wish I didn’t have to work. I never thought I’d say that because I’ve always enjoyed teaching. But partly it’s a sense of time running out. I’m dying now. Talking to you. I hope that as I’m approaching my most productive years in my forties, I’ll be able to work the least and make the most. For the first time there are films I want to make and that keeps the temperature up, but there’s a different kind of pressure now. I don’t even know if it’s fun to make. Walking around in the spaces between the work. Those awful voids where you’re trying to figure how to put it together. What happens if you wake up one day and you can’t make films anymore — you’re dried up? I think every film I make is the last one. I’m not a lover of film, I’m a practitioner. Hollywood film? I’ve seen two in the last three years. I don’t need Woody Allen spending ten million dollars to tell me fifteen jokes in an hour and a half. If I want to hear stories, I’ll go to the pub. That’s when stories are the best, with the warm breath in your face. I don’t need a story when I go see a film, I go for something else. I’m interested in seeing new forms, new constructions of the world. I get so much content just passing through life. Alternative cinema excluding jury work? In three years I’ve seen two Derek Jarman films and a Bruce Weber documentary. That’s my diet of film culture outside my own work. And what I bring to the classroom, which is all the stuff I’ve seen before twenty times but I still like seeing it. I don’t go out to the movies. I don’t like sitting in the dark for two hours. Or going back in the past. I don’t like editing for the same reason. I can’t stand sitting down. How can you like swimming if you don’t like water? Editing means reacting to footage I made six months ago. But you have to keep chipping away at it and find the film waiting inside those first intentions. That’s why it takes two years to make something. Being alone with your images is a tough one because they can control you, put the whammy on you. I’d rather be in the world with my kids but that isn’t how films are made; they’re made in the dark.

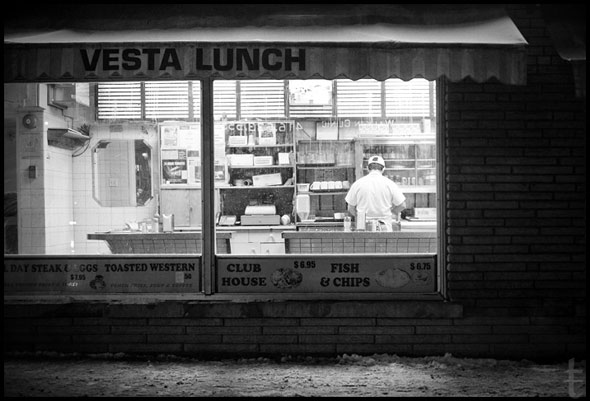

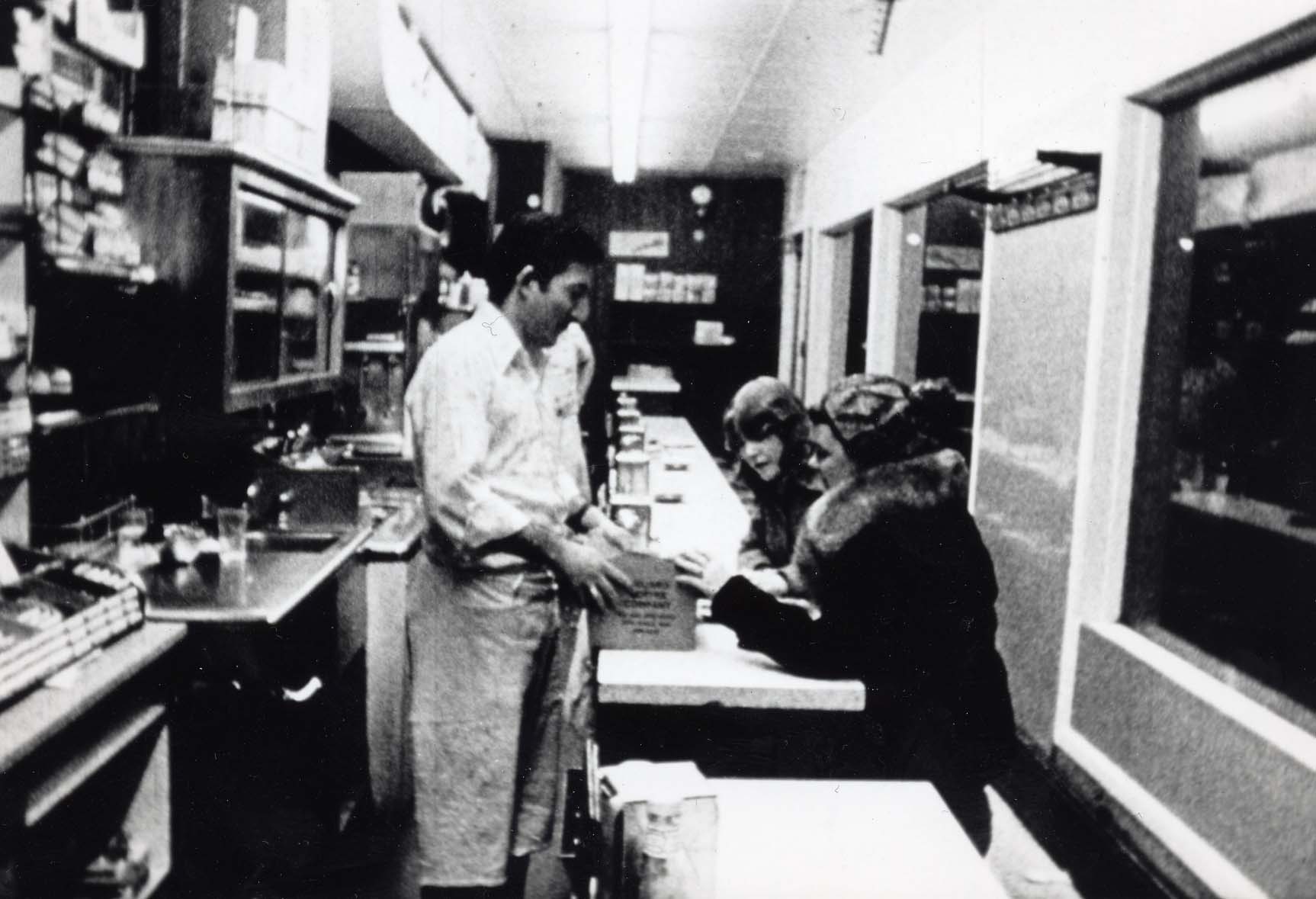

So I’m in film school. Needed a project. Had four hundred feet of film. Interested in continuous take. Interested in Toronto all-night culture because, coming from St. Catharines, I’d never seen that world. I go with the sole intention of letting the camera run for eleven minutes, just to see what it would look like. And something might happen. If you’re there in the right way at the right time you can cause something to happen. This sounds like playing hockey. If you head into the corner, you’re going to get the puck but you’re going to get hit. That’s the verité in cinema verité. I ask a friend who’s driving cabs where we should go, and he tells me about this all-night diner. We head inside and check out the long counter that splits the three cooks from the people eating and decide to shoot down one end of it. We don’t tell them who we are; we just bring the gear in and start shooting. The camera guy had instructions to let the camera run no matter what. Later I thought of coming back every year, just running a roll through the camera and collecting them. But once was enough. The camera gets you into places you wouldn’t find otherwise. But once you get there, you find that having a camera changes a place.

MH: Vesta Lunch (Cookin’ at the Vesta) (11 min b/w 1978) seems less a documentary of the people in the diner than a record of their reaction to the camera.

RK: You have to remember this was just before the news was shot on video, so the experience of reporters walking in with cameras was relatively new. If I went today, it would be completely different. I also directed the film as far as that was possible. I was the sound person, so I put the tape recorder on normal, laid it on a cushion in a corner and pointed the mike around and made hand signals. At one point someone comes in and asks, “Why are you here?” and I say, “Best coffee in town.” And the cook who’s hamming it up the whole time says, “Yes, yes, best coffee in town. Still twenty-five cents.” So without entering the picture I was in it as much as I could be. Someone else would have run into the shot. That was the thinking in those days, to personalize everything. But I refuse to have my own image in my work. My voice is in all of my films, but never my picture.

MH: The cash register is at the front of the image. It’s all business while the background shows the comedy — the cooks and customers. The counter is like the theatrical thrust stage with the cooks performing for the camera. They’re hamming it up trying to advertise their place, but they wind up neglecting their customers. One refuses to pay for his “garbage soup,” and all of sudden you realize that the comedy of the background has turned the seriousness of the foreground into farce. The most striking moment comes when someone buys cigarettes and gets the wrong change. Or says he does. After a lifetime of making change the cook is unsure. He freezes up because the camera’s on.

RK: Making that film was a hunting expedition. I sit down and think, “I’m going to make a film this summer” like some people say, “I’m going after the big horn.” I say, “I’m going after the missiles in the Mojave Desert” or, “I’m going after this all-night diner.” Your outfit depends on how big a beast you have to bring in. Some of us have pistols, some of us shoot with elephant guns. I make documentaries about places. What’s the best way to structure this world? How do you give this place a shape? How much time will it sustain? I go and try to recognize the ideas already there. I’m not really interested in hauling around lights, but I’m very interested in the natural patterns of light, the content in natural forms.

MH: The first films made in Canada were done in just the same way. Small crews were sent out with a camera to places of scenic interest. These short films were shown by people travelling with projectors in the trunk showing strange new work to people unfamiliar with this type of experience. There’s a lineage.

RK: We’re really making documentaries in the Canadian tradition. We’re like the Group of Seven; we’re isolated, we’re trying to grab a spirit and deal with it in an abstract manner. We go out into the world, plein air style, then bring it back into our studios and change the scale.

MH: What’s Canadian about Canadian film?

RK: It’s more personal. It has a documentary quality, it’s more meditative and we don’t laugh at ourselves much. There’s much more adherence to process, it’s more “my world” as opposed to “our world.” There’s a lot more intimate camera work, especially shooting without sound. If there is a national cinema, it’s certainly what we’re doing. Our work reflects more about this country than any other kind of filmmaking. I think abstract work is central to cinema. The feeling of the individual is strongest in abstract work. And that’s so important now because we have to return to the individual. Our corporate communities aren’t working. The world needed the work of Jackson Pollock. And it needs our work. When I look at the films of other makers today in Canada, I see a lot more people dealing with abstraction. I don’t think we’re satisfied with a realistic-looking image. I think we’re looking for new models, new ways of working.

MH: The values you’re espousing are distinctly white and male: strong makers, tradition, the importance of the individual, Canadian nationalism, formal innovation. What does formal innovation mean to families living on welfare?

RK: It’s Saran Wrap philosophy. You cover the whole scene with the same sheet. Let’s look at the work. Some critics are looking at where the work is coming from. It sounds like the argument I got at the Grierson Documentary Seminar, where the Marxist stands up in the back row and asks, “How dare you make a poetic film about the struggles of these boat workers?” I said the film is all about workers, but it’s also about poetry. I can’t control the agenda or the dialogue. Rather than try to gear my work toward the flavour of the week, I’ll just do what feels right. It’s like the carpenter who builds the house; he’s not thinking about what colour the garage door is going to be, or whether it’s going to match the car. He’s thinking: is this Georgia Spruce better than the Mississauga Pine? I understand the present critical climate, and there’ll be a time when my work won’t get programmed. But I can’t worry about that — none of us can. I remember one of my teachers sitting me down at film school and saying, “Richard — you’re in the top one percent of the world. You’re white, male, under thirty, and you’ve got all your hair.” What we’re doing now is working outside the pack. We’re heading in the same direction as these critics, we’re not fascist filmmakers, we’re not denying gender or race — but we’re not making media. We’re making objects. Media flows in a circuit, but we’ve jumped outside that circuit.

MH: Why did you dedicate Canal (22 min 1981) to your brother?

RK: Because I haven’t seen him since then. He left home when I was fourteen or fifteen, shortly after we moved from the canal. I’ve seen him at funerals, that’s about it. We’re from two different backgrounds. We’ve spent more time apart than together. I’ve spent more time without a father than with one. Now with my kids I think, well, my father was forty-two when he died, and I’ll be that old soon, so what if my kids don’t know me? My father left behind sports scrapbooks from when he used to play ball. So there’s this fiction I’ve always had. If I pop a gasket in the next few years, it’s important for me that I’ve made films. It’ll take my kids all their lives to get through them. That’s enough reason to make them. To leave a record so people understand.

MH: In Canal you seem to arrive at your “style.” It’s a documentary shot out-of-doors with many of your favourite themes: fishing, water, men at work, natural light, and landscape. You fragment space and rearrange it into a mosaic of personal details that come together to make a moving picture of your past. This fragmentation takes you away from the more strictly documentary styles of Vesta Lunch or Hawkesville.

RK: I get my material from the real world rather than fabricate. I grew up there, learned to swim watching the boats go by. When I was making the film I spent a lot of time driving up and down the canal, taking in the rhythms of my subject. I knew I had to use a 10mm lens and get in close to the subject, these huge dinosaur boats, not to stand way back and use a zoom lens to pick things out. Canal has a tableau mentality. The camera stays on the tripod and lets the world come into the frame. For me shooting has to do with waiting. There’s only an hour or two a day to shoot my subject. When I’m shooting, the lens cap goes on after ten in the morning until four in the afternoon. That’s the kind of light I’m interested in. The kind of emotion I’m interested in. The least technology with the maximum result. I was proud that I got out of film school not knowing how to use an Arri or a CP. I knew I’d never use them as everyday tools; I always use a Bolex. Someone asked if Faulkner would’ve been a better writer with a word processor. I think it’s a myth that you need big equipment to make good work. It’s what you’re used to. The Bolex is very practical — it’s light, doesn’t need batteries, and the lenses are very sharp. It’s a brush we prefer, that’s all, and not necessarily the most expensive one. I’ve gone back to an editing bench recently. It’s partly a political move — the students come into the office and see a bench and a lightbox. It’s a way of getting close to the materials. That’s why video doesn’t interest me. The materials are always in the machine and you can’t pull them out.

MH: Canal is filled with a lot of stopping and looking, and when you stop you hold up, you suspend. A suspension not of disbelief, like in a fiction film, but of narrative itself. There’s a flow that runs through the whole film — of water, and boats, and men working, but in order to see them you have to step out of the normal course of events. So you stop looking for a narrative founded on causality, and turn instead to a narrative of attention. The camera examines the shore markings like Egyptian hieroglyphs, staring fascinated at a natural evolution which it attempts to read like obituaries. They show the passage of all those ships which have crossed the canal, even as these ships pass ceaselessly through the frame. In the ships’ momentary appearances and the camera’s patent refusal to follow them, Canal becomes an obvious metaphor for our own mortality, for a current bearing us all inexorably towards our own end.

RK: I’d be happy if that was the critical epitaph. I work on film because it all rests in one can. They’re tombs. Markers. You make it and leave it behind. It comes from finding my father dead in his bed and having to close his eyes. And going out to sit on the porch and wait for my mother. And tell her he’s dead. She died shortly after that. Now that I’m starting a family again there’s a different sense of mortality, a different reason to make work.

MH: How did On Land Over Water (Six Stories) (60 min 1984) begin?

RK: I was taking pictures while living out in Waterloo County and started seeing the Northern Ontario equivalent of the mirage — these heavy skid marks on the road. I thought there must have been a hell of a story behind those tracks. They were icons of the rural experience that had been my whole life and that’s where my next film really started, with these road signs. There was a lot of interest in those days about new talkies, new narratives; whatever was new seemed to have something dramatic attached to it. So I started thinking about making a fiction film. It was going to be called Rural Stories, relating myths of the guy who could drive the fastest, talk the loudest, drink the hardest — real rustic male scenes. That’s what eventually became /i>On Land Over Water (Six Stories). It would just be guys telling stories — all dramatized with real people and actors. I got $10,000 from the Canada Council and headed down to Key West, Florida, to start shooting. When I was fifteen a bunch of friends decided to drive south to the Keys. The car broke down outside of Ingersoll so we hitched the rest of the way. Never thought of heading back; it seemed easier to go two thousand miles south rather than hike the sixty miles back.

It was the trip of my life. Rides with drunks, with guys packing guns, sleeping on doorsteps, meeting homosexuals for the first time, running out of money, panhandling, sleeping on a marine base and then Tennessee Williams’s front lawn. It was every trip a neophyte dharma bum could ask for. So I wanted to go back and recreate this trip — the first of my drives into America to shoot. I filmed all-night garages, the hucksters on the dock, the fire eaters, the baton twirlers and a lot of shadow characters. Impressions of the area. Meanwhile I still wanted to work with actors. I made a big casting call but couldn’t give anybody a script. I thought you’re the actor, I’ll let you know what I’m interested in and you act. I was really resisting this kind of filmmaking but thinking it’s important to do because everyone’s talking narrative.

I was very impressionable then, really resisting the film I should be making. Phil Hoffman and I are looking at people and shooting video. We cast a woman — the first in a line of films without men. We’re up at Phil’s cottage. The first weekend the light’s not right. I make the call and we head back. The next weekend we go up and shoot At Her Cottage in two days with this woman and her child. The best collaboration I ever had. This woman understands what I want. I’ve given all the Hemingway to her. It’s all improvised and it’s working great. But there’s no lip sync and she says: When do I have my monologue? When do I talk? So we set up a shot at night lit by the fire and the camera’s panning through the trees and I just tell her to wing it and she comes out with this story about Jack the drunk falling through the ice and dying. I stand back floored, thinking she got it all; everything this film is about is coming out of her mouth and there are no mistakes. Because you shoot one-to-one on these films, there are no second chances. This is all live. She just ran it flat off the top of her head.

I was excited. I had two weeks, a truck and a little bit of grant money left to make this film. So I took the equipment — a CP and a Nagra — and I drove around Toronto. I’d call up Phil everyday and we’d look for things. We went down to the boats, Cherry Beach; I know that area. So we made Drive To Work, which just shows a ten-minute take out the window of a car looking out at the boats on the dock. I’m wondering how I’m going to connect this with the other stuff. You don’t get to do this very often where you’ve got the gear, the truck and the dough. You’re living your film but the clock’s running. We drive around some more and see these two little black girls skipping in front of graffiti which says “Spirit Astray.” We go, hey, that’s a shot. These kids could be related to the guy who’s in Florida, who goes to work on the boats, who’s with this woman at the cottage. Jump out of the car, buy some popsicles for the kids, and one tells a story about crossing the street against the light and the teacher suspends her from school. It all connects — they’re outsiders. Young kids with a story to tell. Once again I didn’t have to make up the story. Momentarily, for that hour, I’m feeling good.

Then we cruise north and I see this guy who looks like Davy Crockett standing outside this store. It says “Four Seasons Taxidermy.” And I say, hey, that’s the guy. That’s the guy who’s down in Florida, who works on the boat, who’s with the woman, and he knows these kids. All these crazy stories are going through my head. We go in and the hustle isn’t easy. He thinks we’re cops, so I buy a case of beer and try to talk. He’s burned out by the glue that he handles every day. But this place is just a rich museum of Canadiana, filled to the roof with stuffed animals of every kind. I’m starting to have these plans that he’ll invite us north to go trapping and we’ll go along and shoot but it doesn’t work out. We decide to do another one-take wonder. We start up the camera and I say, “Tell me the story about the shotgun” and the camera starts walking into the store. He’s telling this story and I’m flashing Eugene O’Neill — you know, if you show a gun in the first act you have to use it in the third. It’s one of the laws of drama. It’s all coming together. He keeps talking and though we haven’t rehearsed anything, he walks straight to the back of the shop and stops like an actor should stop and picks up a shotgun and cracks it open and delivers his story. It’s about a friend of his who let off a shotgun to scare him and he did the same to his friend and that’s why there’s a hole in the ceiling.

Now my two weeks are up, the equipment has to go back. So I check into the Penthouse to edit, the cheapest steenbeck in town. It was always too high for me; I thought I’d jump from that height. I like to cut on the ground floor. I start putting the film together figuring all these sequences will intercut. And they don’t. I even brought the script doctor, Alan Zweig, in to have a look at it, and he’d look everything over and run back to his apartment and write something to tie it all up and it would come close but never quite seal the works. Just to take my mind off this nightmare I was reading short stories at night and material around short stories — why doesn’t anybody write this stuff? What’s happened to this form? And then it dawned on me that’s what I had — all these short stories. I had five of them. I was reading a lot of Hemingway and especially Indian Camp, which is my favourite and thematically covers everything I was doing. I had a first edition book and one of the letters was smeared, one of the t’s from the typewriter dripped and I thought, wow, that’s like the skid mark, one of those beautiful imperfections. Then I started looking at the shape of the words, after reading the story for meaning. Thinking “jack knife” would look great blown up on the screen. Hemingway was good at using words like that; physical language was part of his modernist bent. I got the pages blown up big and filmed them in my apartment with a Bolex, and when that was finished, I knew I had it. It would be called Six Stories. I went back and cut it pretty quickly after that. Once I became aware of the film’s themes it was a little frightening. About masculinity and male myths. I wasn’t overly conscious of that. I haven’t looked at that film in a long time. It comes out of a very lonely period. My last bachelor film. I realize how slow going it is. Once in a while, not very often, I put on one of my own films. To find out something about myself. Not about the work but — what is this point of view? How clear is this guy?

MH: So what does this film say about masculinity?

RK: That men bring darkness and evil. If you read the first story closely it talks about a doctor going into an Indian Camp and delivering a child. After the delivery he finds the woman’s husband on the bed is dead, his throat cut open. But there’s an implication that the doctor’s brother killed this guy, so whenever the story refers to him, the screen goes black. In the Shotgun Story this guy isn’t selling subscriptions to the Red Cross, he’s selling stuffed animals. The male myth ends in death. The junkies in Key West. The drowned drunk in At Her Cottage. It’s not a romantic world, there’s not a lot to celebrate. I got a print at Northern Labs, which was just going out of business so they never made me pay for my last bill. I was flat broke but I had a print. This was 1985. I tried to show it at the Funnel and they said it was a “masculinist” film. People don’t go to their toughest critics first. They go to their friends at the co-op who tell you everything’s all right. I showed it to some people straight from the lab and one woman, a cultural critic, told me, you can’t do that, Richard, that woman on the boat in At Her Cottage is being held hostage with your penis-like camera. Penis-like camera? I got excited. I said, no wait a minute, there are all these themes running through an hour’s worth of film and a lot of it’s symbolic, etc., etc. I did what any filmmaker would do — I stayed up till four in the morning buying them drinks and defending the work. She said no. Then it didn’t get shown at the Funnel for almost a year. Then Bruce Elder took it up and wrote on it for C Magazine. That helped a lot; it legitimized the work. It got into some festivals, so it worked out in the end. It was a tough struggle because it became an issue film. It’s weird that such a cumbersome film would get taken up like that. There were other films that cut to the bone a lot quicker. It didn’t help resolve my narrative itch. That was still in the air and I wasn’t absolutely anchored in my own filmmaking. I was still listening to people. I wanted to leave Toronto. Too much film in the air. Too much careerism. Too many movements. Art had changed by then, all this postmodern stuff. Everybody’s talking about it, but nobody can define it. It’s like boxing with shadows. I’m married with a kid, I’m making eight thousand dollars a year, fire breaks out in the apartment next door and I’m not happy here. I don’t want to make films anymore but I gotta. Then the opportunity to teach at Regina comes up and I leave. I don’t know anybody here. No one does, no one’s ever been here. In 1985. The momentum of my film along with some rock videos I made for the Parachute Club landed me the job. A little bit of show biz and a little bit of your own poetry — ostensibly a perfect mix. [laughs]

There was a long time and a lot of miles between Six Stories and The Last Days of Contrition (35 min b/w 1988). It began as a grant proposal about this fire boy — a Rumblefish type that lived in Port Colborne, an industrial wastesite where they used to take apart the great boats. His mother dies and he begins to search through photographs trying to put together her life. That’s obviously not the film I made. I write the proposals so they make interesting reading — they’re just the starting point. Still thinking I’m a dramatic filmmaker, I head back to Toronto to do some more casting. We found a guy, headed out to Port Colborne and everything was terrible. Wasted two thousand dollars. Bird shit on the lens. Fired the cameraman, fired the actor, and started over. I decided to head south to Buffalo, packed up the Bolex, and drove to the ballpark, where I spent the two best days of my life filming. I was in a medium I knew so well. The War Memorial Stadium. If you wait long enough with that kind of shooting, you’re going to find something to bring home. Then I drove with a friend down to Taos, New Mexico, and we stopped en route at SAC airforce command to shoot missiles. That’s when I moved to Regina, found a house and hunkered down with this baseball footage. I don’t have a clue what do with this stuff, but I’m gaining this incredible enthusiasm for filmmaking again. All of a sudden there’s no one to talk to or distract me. So I started tinkering with film again — back on the rewinds, getting drunk and putting images up on three projectors with cassettes running in every direction. Film is fun again.

I took another trip into the southwestern States through the deserts and the mountains. I picked up some more military imagery, and started filming abandoned landscapes — broken down trailers, abandoned cars, that kind of thing. When I came back I needed one more item and remembered the Moosejaw air show in the fall. I went out to shoot the jets like there was an invasion coming on. Soundwise, I’d saved all this late-night American radio chatter — the weird freaks, the hypemongers and conspiracy nuts — and started laying some of that in. Hemingway resurfaced with Poem for Mary, read by the author for a record that came out in the forties. I still felt there was something missing, so I went back to the actors one more time. Found a man and woman. Shot about an hour of sync studio footage, which I thought would wrap it all together. All stationary camera.

For the longest time I had an hour-long film I felt was finished, complete with mix. For all intents and purposes, the film was done. I hadn’t shown it to anyone because there was no one I could really show it to. By chance it was a weekend I’d organized at the film co-op, which brought together Stan Brakhage and Bruce Elder. I asked if they would look at it. My first feedback in three years. As soon as I laced it up, I knew it wasn’t finished. I thought, “I don’t like that shit with the actors in it. It slows it down.” So I put it on, the film is running and Brakhage is saying, “Omigod, why do you guys hate America so much?” But he’s landed in the middle of nowhere and he’s watching some rigorous stuff. He’s liking the film until it gets to the acting bits and then it just dies. In vaudeville they’d have the cane out. There’s another montage sequence, which is fine, and then the actors return preceded by an intertitle which reads “Out There.” And Brakhage turns to me and says, “Oh I’m sorry, I thought it said ‘Cut there’.” [laughs] That’s the kindest way to put the cruelest thing you could ever say. After they left I just snipped the actors out and the film was finished. I didn’t even have to redo the mix. The actors came out like a circuit board from a computer, like it was modular. It felt like a first film. The first film I made outside Toronto.

MH: How did you come up with the title The Last Days of Contrition?

RK: I cut the film in this room — the NFB outpost in Regina. I was finishing up the film, so it was just about title time. You know what it is, now you got to name it. The Film Board was throwing out a lot of film which I dutifully hauled in a truck back to the university. I came across one which read The Last Days of Living. So that’s what I called it. I was developing film through the National Film Board when I got a fax saying, “We will no longer do any work on this film. This is a Film Board title.” I could have protested, but who cares? If you’ve got the money, I can change the title. I had all the Hemingway poems out and came up with the word “contrition.” I was cutting with a woman and wrote out six titles. She was a lapsed Catholic so “contrition” rung heavily with her, so we went with that one. Wherever I go, the first question is always: what does the title mean? I had to make a few “Pope” calls to my Catholic friends to check out the meaning, not the dictionary meaning but the sense they made of the word. And it was all right.

MH: It gives the film a despairing and biblical air. You enter America only to find it abandoned, a land of deserts and ruins filled with the sound of voices without bodies. Then the military motifs are introduced providing a rationale for all that went wrong, the endless trains transporting tanks across the wilderness, the jets looming overhead, the aggressive sounds of military hardware and computer terminals. The film is a kind of elegy for the promise of constitutional ideals left behind in the pursuit of arms and arsenals. Why were all the spaces you photographed abandoned or ruined?

RK: That was the task at hand, so that’s where my eye took me. To look at a world and find the emptiness in it. My eye focused on that for a year and a half, and you’re only good when you have that focus. There’s always a turning point for me — some image that lets me know where the rest of the film is headed. In Contrition it was the train carrying tanks and my daughter playing in the desert behind it. That’s when I knew what the film was about. It took a lot of driving, close to 20,000 miles. Some people sit and write scripts. I have to drive and look.

MH: There’s a lot of driving in Plein Air (20 min 1991); it looks as if the whole film is shot from a car window.

RK: After moving to Regina, I drove back to Toronto several times over the next few years and started shooting the landscape of northern Ontario — the Canadian Shield. Plein Air was shot with an Eclair because it has a variable shutter. I knew after shooting the hoodoos in Contrition that stopping the shutter down to ten degrees produced a strobing image because every frame is very sharp. I knew I could apply this strategy to the northern Ontario landscape and flatten this landscape out as I went along, shaping it as a painter or sculptor would shape renderings of the same landscape.

MH: That recalls something Brakhage once said: that when he looks at a painting he sees how a painter has fashioned a tree out of a single gesture of paint. These gestural renderings ,are similar to his own, as his camera inscribes a tree in space, signing it like an autograph.

RK: It’s a very modernist consideration. Here was another place I wanted to live with and document. It starts out with many layers of the Canadian Shield, fields of rock with up to four images superimposed. That lasts about eight minutes. Then there’s a section of road construction and roadside technologies that pass in a kind of catalogue collection: steam shovels, satellite dishes and logging trucks. Then we move into a sequence still heavily layered with the Canadian Shield. All of a sudden a train appears travelling in every direction, superimposed on three and four picture rolls printed together. Most of the natural footage is green, but the train is red and orange and rust coloured, so there’s a nice colour intersection. A sunset follows looking out over a lake as the sun goes down and a family boating expedition packs it in. The same shot’s repeated on different rolls and printed altogether. The film finishes by going through landscape showing staggered repetitions that move over a hill into the space of the horizon. It moves into a Northern Ontario village before flattening right out to blue sky, physically and metaphorically “into the blue.”

MH: Much of your work’s been characterized by an almost stately, deep-focus documentary style photography which relates isolated individuals to a rugged environment. This film seems a real departure.

RK: Plein Air is true to my experience of Northern Ontario. It would be false setting up the camera on the sticks and making calendar shots. Believe me, I’ve tried it. The footage didn’t work. Physically the Canadian Shield is very claustrophobic. It’s not the kind of space you want to see in detail; you want to see it in massive abstract chunks. Because there’s so much of it. Because it takes you two days to go through it. It’s a landscape I’m so familiar with, that I had the confidence to impose a structure on it before shooting. There’s no questioning in this film. The form is locked in from the first frame. The Canadian way to deal with our landscape it to mediate it through technology — to frame and contain it. The car is the movable garrison that takes us through this hostile environment. I made a whole film of Canadian icons, the same thing I did in Contrition: totem poles, outpost hot dog stands, the big muskie. But they just weren’t very cinematic. The weird guy at the outpost talking about moose, I got all that on film. But I didn’t use it in the end. It became this very formal work. It just didn’t have what the American stuff had. The American stuff is much more extreme. The North is scary; there’s nothing like it in the States. In Northern Ontario you can drive a day and a half without coming across anything, whereas even in the northern-most part of the States, there are drive-ins and hot dog stands. It’s a different way of looking. America is more fun to go through; there’s always something to look at. It’s like that song by Gordon Lightfoot, “The silence is too real.”

MH: What about Plein Air Etude (5 min silent 1991)?

RK: That was made at the same time. It’s five shots, each repeated many times. It begins with a seventeen-second, single-frame shot of these round stones up at Lake Superior. They resemble giant film grains, very organized in their arrangement. I made five different seventeen-second gestures sweeping across the rocks. Then I laid them out on five image rolls, taking ostensibly abstract images and moving them inside a methodical structure so they’d play off one another. I followed the same basic method with each of the five shots of the film. I took the images of the sunset into the darkroom, pressed colour filters onto it, and used a flashlight to generate different tones. Is it a film? I don’t know. It communicates nothing. There’s no content in either of these films. I think there are ideas about painting and filmmaking. Maybe all this modernist stuff is a cry that film is near the end and there are certain things you want to do. Who knows how they’re going to look at film twenty years from now? My guess is people are going to be very interested in formal experiments like Ray Gun Virus and Tony Conrad’s films. I’d like to bring some of these modernist ideals back as ways to express emotion. Someone said that I’m really making a series of chase films. I thought that was an interesting comment — all of a sudden my films have a lot of movement in them. I think he was right, that I am being chased. By time.

MH: You’re involved in another project right now which is quite separate from the modernist concerns of Plein Air and the short study. It’s a relatively big budget, feature-length dramatic work with actors and crew and script.

RK: I got on the industrial model machine just because I can, that’s all. I’m not about to mortgage my house to make a feature film. I’m very calculated about the whole process. It’s a business. Because I’ve done a little bit of commercial work for the Parachute Club band and received a couple of Juno nominations, I can almost be sold to Telefilm even though what my real work stands for has nothing to do with them. If the film gets made, I have a chance to do something very different in my filmmaking. That’s the worst case scenario. The personal element is really removed from this so it’s easy to deal with. It’s being written for me. Someone else is producing it — it’s all just being carried under my name. The minute this film becomes personal to me in any way, then I’m fucked. Then I’d become the victim of the system because I’d really want to make this film and do anything to get it made. I can justify that with my own films to date — going over budget, taking two years to finish, making radical cuts at the last moment. You can justify all that because you’re so passionately involved with it. This other film is a venture. Experimental filmmaker gets to make low-budget drama. It’s a long shot that any of these big films get made anyways. But it just so happens that I’m living in Saskatchewan, they have a film fund, they’re giving away money, and because I’m one of the few filmmakers here, they’re going to give me what I need to do this. So I can hire a writer and lawyers and producers. I’ve spent more money than I’ve ever had for one of my own films and I haven’t shot a thing or had anything to do with the project. I picked out a photograph and asked the writer to make me a story about it. So he wrote a story. It’s weird. But people tell me this is how you make films.

MH: What you’re describing is a real schizophrenia in your making — between private and public, between a solitary, abstract art making, and a big-budget drama with actors and crew. There’s even a moment which signals this divide. You’re sitting at the Steenbeck looking over the shoulders of Bruce Elder and Stan Brakhage to see your own work, which is part dramatic, part experimental film. That’s when you decide to toss the drama, feeling that the two parts don’t belong together. And as the dramatic urge grows into a more public expression, adopting a film form the public has learned to understand, the experimental urge likewise deepens, becoming increasingly hermetic, enclosed and abstract. It’s a curious duality, and one which I think is not untypical of what many makers are feeling in this country.

RK: I also have my first gallery show coming up. They’re going to screen all my work and have asked me to make some wall art, and they’re going to do a catalogue with all the trimmings. So what will happen in 1992? The gallery show will definitely happen. Most features don’t get made. Where will I go with my single screen work? If I go the visual art route, then my films would become more modernist, which means working by myself. If I go the other route it’s the country club. I come up with ideas and get a crew to execute. Like Yogi Berra says, if you see a fork in the road, take it.

MH: How much do your films cost?

RK: Hawkesville cost $600 in 1976, Vesta Lunch $230 in 1977. For Canal I got a grant for $4,500 and it cost about that much, maybe a bit more. Luck is the Residue of Desire was another out of pocket film. I got a small grant from Ontario Arts Council to finish it, around $3,000. Then Six Stories got a little out of hand at $15,000. Contrition was more expensive because of the travel — $30,000. Plein Air, $10,000 because of the lab work, the A,B,C,D,E rolls. Cruel Rhythm will come in at $65,000 because I’m hiring people — an editor, composer and camera crew. McLuhan cost virtually nothing — $2,000. None of this is labour — otherwise they’d be million dollar films. Willing voyeur has a global budget of $600,000 which is full of deferrals, services, and training money. We’re state filmmakers, so films have to be made a certain way. We’re not truly independent. Canada is a socialist country which allows us to continue to make work through the arts councils. But there are films I want to make that I’d never approach the Council with — more abstract work. Shorter films.

MH: With these new possibilities to make dramatic work, do you feel differently about including stories in our fringe films?

RK: I’m a high school drop-out, so why expect to see a lot of words in my work? I never did pass a grade in high school. It’s ironic that I’m a tenured professor now, but… I’ve never dealt with the theory stuff. I’m a pretty verbal person, I just don’t feel that film is a good conduit for that verbalization. I don’t make films about stories or theories. I make films about places. Plein Air is about Northern Ontario. Six Stories is about six different places. Vesta Lunch is about a city diner. Canal is about the Welland canal. Contrition is about the American southwest. I don’t know whether I want to deal with memory so much; memory drives something, but it’s not finally of interest. At some point you just go there with a camera and hang out and wait for something to happen. I try not to philosophize or theorize before getting there. You’re looking for the pearl, and once you’ve got that first shot everything rolls from there. It’s like going fishing — sometimes the fish are biting and sometimes they’re not. When I met people I used to want to know all about them — where they’re from, where they work, do they have relatives — all those questions. But I’ve lost that feeling in the last few years. There’s no need to know about anyone’s past anymore. It’s become so prevalent in Canadian film, returning to the past, the family, it all looks the same to me, it all looks like the same family. I don’t want to start my films in the past. I don’t want to begin with the past in order to go on. I need to start now. As a culture, we’ve sorted out our past. The imperative is to deal with the present. The white male ways. The gay ways. The working class ways. The people of colour ways. We have to go on. Looking.

[The next part of this interview was conducted four years later, shortly after Richard finished his feature film.]

MH: Your next project was a video called McLuhan (60 min video 1994).

RK: It began with some of the first images I ever shot. I was just standing around Sheridan College when the dean came looking for someone to document Marshall McLuhan. I didn’t know who he was. We were given a quick workshop on those old reel-to-reel video portapaks and sent down the highway to the School of Design. McLuhan gave an hour-long monologue about media and literacy. For twenty years I hung onto the tape and didn’t know what to do with it. I’d pull it out once a year and look at it, and over the years learned more about him. Finally, it’s more important what I didn’t do with the tape — I didn’t edit it. I tarted it up a bit, superimposing some video snow to give it rhythm. Then I put McLuhan in a box with a back frame around him. On top of the box there are headlines, bytes taken out of his speech like, “Nudity is never naked” that flash on and off. I had his rap transcribed and ran it as a scrolling text below the box, which sometimes runs ahead or behind of what he’s saying. There’s no additional sound, no music or effects. It was probably one of the more pleasurable pieces to work on because there was so little at stake; it was about someone else. The “catharsis investment” was low and that was nice. I’m glad after twenty years I found a form for it.

MH: Your next film willing voyeur (75 min 1996) was something of a departure — a bigger budget feature with actors.

RK: The whole dominant cinema, now that I’ve had a taste of it, is too much like manufacturing. You make a blueprint, the script, you organize everything, you get a schedule, everything runs on a clock. You’re working in a medium that’s all about time, but time is the biggest enemy. To me that’s manufacturing; it doesn’t leave anything open enough for serendipity or spontaneity. I’m a hunt-and-peck type of filmmaker — I have to go out and gather these images from the world and then rework it in my studio.

MH: There’s a sense in much of your work that something is missing, and that you’ve come with your camera to record its absence. In Contrition America has been devastated and emptied; in Canal these ships are passing away and your brother’s absent; in Machine space itself is erased entirely.

RK: There’s always been a sense of loss. You feel the clock ticking all the time. I tried to break that conditioning with this feature film, but it never happened. I had all the machinery to make it accessible — with a beginning, middle, and end in that order and the right beats on page ten. But I couldn’t do it, I don’t know why. No one dropped an anvil on my head that killed narrative when I was a child. I don’t think I was excessively lied to and therefore distrust stories.

MH: How did you find your way into this kind of making?

RK: I spent two or three years getting hooked on Stan Brakhage. I got to know him, mostly through correspondence, and became as deeply affected as one can be. I’d done Plein Air, Machine in the Garden, and enjoyed them but felt exhausted by the whole idea and thought maybe he’s the only guy that should be making experimental films. You know? It was time to fold my tent and quit working, which is virtually impossible. They’d have to cut off your hands and gouge out your eyes and still… But I didn’t know where to go. With the feature I saw an opportunity and went for it. I made a pact with the devil and paid for it. I knew from the get-go that it probably wasn’t going to happen the way it should. There was a kind of deceit I was carrying in myself. I sold the film on the fact that I would train the B team; the A team are the ones that do the commercials. I was going to take ex-students and upgrade them, take a guy who was a camera assist and let him shoot — that kind of thing. That’s how I talked them into giving me the money. They could sell that idea to their bosses. So you got everyone sitting around a room lying to each other. It was frustrating because that’s not the world I come from, you never talk about where the money comes from because there is none. After awhile I didn’t even read the scripts Alan sent me because I sensed that when I got out there and started shooting, the script wouldn’t matter. I like to set up the shots, tell the actors what the film’s about, and let them find their own words. Voyeur started with a photo made in Buffalo by Russel Sorgi called Suicide which shows a women jumping from a window while people below are doing their business. One guy’s getting his hair cut; there’s a cop walking down the street, and they don’t look above them to see this women falling to her death. We came up with this notion that there would be a snuff photo session, shocking tabloid photos. There would be a couple who find a victim, take her picture, publish it, make some money and split. The murdered body’s found later at the train station. You don’t see the session like you would in a melodrama, but it’s recounted in voice-over by various characters. There’s an eight-minute dolly shot in an abandoned VIA Rail station that’s been broken up in the editing and appears throughout the film. There are six body bags, and a bunch of generation-X street kids sitting around listening to an old man tell tales. It has a round-the-campfire feeling. He’s the one who tells the story of the photo session. His monologue touches upon how these bodies turned up at train station.

MH: Two women appear often in the film.

RK: When Alan Zweig wrote the script it was a guy and a woman. I start working with guys and hear the stories they tell and they sound too much like me. There’s nothing fresh about it. So my curiosity wanes pretty quickly. Inevitably, I start looking for women because there’s something else there. Against his strong recommendation I changed it to two women. In terms of giving them direction in the traditional sense, I didn’t. I changed their character from scene to scene — I’d say now you’re the bad one. They’d ask, “What do I know?” And I’d say, “I don’t know.” This worked because it kept them off guard and gave them a jittery quality. Their uncertainty projects itself. There’s no money back guarantee with these stories. That’s purposeful. To leave them open. That’s also why this film will have a hard time finding an audience. One by one I’m finding a fan here and there; that’s the way it’s always been. It’s a good sign that films are a little difficult. Marginality is a good thing for all of us. I think it protects us, gives us some room to move. This conversation is full of comments like “Twenty years ago, fifteen years ago…” There’s a feeling that we’ve sort of made it through, because we’re still making work after all that’s happened. And that’s what is important now. I think I’m just getting the hang of it. I think I can start shedding some of that white, WASPy, inhibited skin that’s surrounded me for so many years. I tried to do that with this film but couldn’t quite get at it. It’s a certain honesty about what you really want to say, picking the scabs off your consciousness and getting it out there, thinking about the life you’ve led and haven’t lived. I’ve never articulated the most dramatic moments of my life, like finding my father dead, or finding an aborted baby in a field with a crucifix around its neck when I was twelve years old. Those things drive home an existential nature, the distrust of everything. I never expected to make it this far. Making this film I thought the program was finished, and that’s an awful feeling, that was the System getting to me, not the filmmaking. I come back now in the third act of my life feeling more rage than ever.

Richard Kerr Filmography

Hawkesville to Wallenstein 6 min b/w 1977

Vesta Lunch (Cookin’ at the Vesta) 11 min b/w 1978

Dogs Have Tales 9 min b/w 1979

Luck is the Residue of Desire 15 min silent 1980

Canal 22 min 1981

On Land Over Water (Six Stories) 60 min 1984

The Last Days of Contrition 35 min b/w 1988

Plein Air 20 min 1991

Plein Air Etude 5 min silent 1991

Cruel Rhythm 45 min 1991

Machine in the Garden 20 min 1991

McLuhan 60 min video 1994

willing voyeur 75 min 1996

Originally published in: Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada, ed. Mike Hoolboom, 2nd edition; Coach House Press, 2001.

Beginnings: Richard Kerr

Richard Kerr is part of the Escarpment School — a group of filmers born and raised on the Canadian Shield. Their work is autobiographically inclined and well versed in the histories of fringe cinema. Their imagery is landscape orientated, technically adept, and formally innovative. Kerr is a self-described “documentary-essayist,” exploring aspects of male mythology with a keen eye for natural light and rugged exteriors. His images provide a rural arcana of the Canadian male: missile sites and fishing posts, taxidermy shops and baseball stadiums, ocean-bound freighters and all-night cafés. But far from celebrating a rhetoric of bravado, he is quick to interpose his isolated protagonists into a vast and overwhelming landscape, where they travel through arenas of loss. His landscapes are emptied sites, abandoned docks and deserts, the camera forced to stare in an act of memory and mourning, his protagonists left to wander through the signs of an abandoned rule.

Kerr’s cinema is an elongated reaction shot to the news that the Father is dead. Privileging natural settings, Kerr’s elegant photography narrates an aesthetic of absence. The natural world displays the wounds of abandonment, filled with signs we are unable to read because of this broken compact between father and son. Without the father’s presence, the son is left to wander in the space of re-presentation, groping in horror towards an absent centre. Here stories are merely fragments, parting bits of an meta-narrative which can no longer account for the whole. His characters are shaken survivors, scanning a post-apocalyptic universe that has left them with incomprehensible signs of the past. His incessant drafting of an exterior space asks that we pore over our geography like some ancient rune, in search of the cartouche which will allow it to speak to us.

Kerr’s restrained observational style is evident in his first film, Hawkesville to Wallenstein (6 min b/w 1977), his sublime record of an Amish carriage shop framed by a snow covered trek into the farmers’ markets of Kitchener. It is fitting perhaps that his first film should begin with an evocation of cinema’s beginnings: Kerr’s camera follows the horses of the Amish, recalling the famous pre-cinema serial photographs of Eadweard Muybridge. Like Muybridge, Kerr is not attempting to reconstitute a life or render a cosmology; his attentions are turned to the fragment, to what Roland Barthes termed a “science of the particular.” While the movements of Muybridge’s subjects are invariably measured against a grid backdrop, Kerr’s subjects (horse and carriage) move into a landscape that has fallen under the sign of erasure, rendered uniformly white by an incessant snowfall. Once inside, Kerr illuminates the smallest of gestures in this transfer of goods from one century to the next: the Amish weighing, measuring, and wrapping their Protestant inheritance. Their prohibition against the machines of the twentieth century has insured a continuity of horse and carriage as well as a hand-crafted economy left behind in their neighbour’s restless quest for the new. The only colour here is in their cheeks; the Amish wear black and white, a decision the filmmaker reflects by photographing in black and white. Kerr punctuates these market scenes with sharply interposed shots from out of doors. The market’s linguistic island offers the most temporary of respites before giving way once again to the ravages of a storm that threatens to return the world to an undifferentiated state, like the biblical flood. This alternating measure of inside becoming out joins the carriage ride with a warm-hued scene from summer, set inside a carriage shop, where a family unloads a newly arrived truck filled with wooden spokes. Swaddled in scarves and overcoats, the children already seem old, as if the task of stopping history had set inside the bones at birth, that they could look forward only to times already past. As the camera gazes on at their reinvention of the wheel — old hands turning unfinished rounds into the handsome wheels of their transport — broken voices emanate from the track. In this familial setting it is the father who speaks, or tries to, only managing to say “They don’t have no name for it.” And this nameless mystery bent to the rule of revolution, understood here in its pre-modern sense as a cyclical succession of restitutions, suggests a consciousness given over to the gestures of work and love. It is as if, in their refusal of the body’s technological extensions, consciousness had come to reside within their own limbs, belying the expression of Dada poet Tristan Tzara that thought is made in the mouth. Hawkesville to Wallenstein closes as it began, with a horse-drawn carriage ride, sheering off this impressionistic fragment of Amish life with the evocation of a journey that speaks of a homeless wandering, of a place between Genesis and Revelations, between a word and its referent.

A year later Kerr produced the vérité study, Vesta Lunch (11 min b/w 1979), an over-the-counter look at the smallest of thefts in Toronto’s tiniest and greasiest late-night eatery — all told in two real time takes joined mid-film by a dissolve that shatters the truth of its transparency. Photographed in gritty black and white from the eatery’s exit door, the restaurant is shot from one end of the diner’s narrow rectangle. By introducing his camera as the central character, Kerr’s film remains in dialogue with an older documentary tradition while at the same time avowing the image as a site of construction. A new kind of “live” quality is thereby achieved — while the Vesta cooks are clearly not behaving as usual, they are responding in unrehearsed fashion to their new visitor, the camera. What is disturbing to note is the way in which the camera degrades their behaviour, signalling the triumph of representation over presence. Their inability to “broadcast” an image learned on television, to become a kind of live television program, makes them victims of the camera’s impassive stare. The need for fiction is everywhere present here; it suggests a role for the observed, whose daily circumstance in no way prepares them for this surveillance despite the surfeit of images which surround the diner.

After spending the next two years photographing the wilds of his childhood, Kerr finished Canal (22 min 1981), a painterly document of the Welland locks. All of the elements of his mature style are in evidence here, most notably the weave of landscape and autobiography achieved in a montage of precisely framed sites and textual overlay. The opening trilogy of titles: “to my brother/Canal/a place in our youth” names Kerr’s project as a nostalgic one, as a return home through history. This quintessentially Western project, begun with the founding text of Western literature, Homer’s Odyssey, typically features a seafaring protagonist engaged in actions of deferral and delay which become the plot of a tale which ends as it begins, his return marked by the naming of its protagonist. The canal of the film’s title signals Kerr’s own return. Yet he returns not to resume a lost authorship or to redirect a vague and watery excess into channels of his own making (to canalize). Rather, his photography allows a succession of slow-moving associations to gather atop a watery support. Kerr’s gesture of correspondence turns camera into canal for a stream of images laid along a narrow transport of emulsion and sprocket hole, pausing for exposure in the “lock” or “gate.” This strategy of formal imitation shows the canal as a site of admission, a taking in of an excessive present, a present that manages to exceed those patterns of the past that allow us to see at all.

After titles announcing “canal closes for the winter/boats head home for Christmas,” the camera moves from shore to ship, slowly panning over the vast machines that float their cargo through the lock. Turning the helm in the midst of a raging sky, a captain struggles for birth inside the canal before a lap dissolve returns us to summer, the passing banks now photographed from onboard. The third and shortest of Canal’s six movements is a dramatic one. After this riverboat pan, intertitles state: “a witness to a boy on a dirt bike/getting killed by a truck this summer.” What follows in illustration is a dramatic re-enactment. We watch a motorcycle rider — his head swollen and obscured by a racing helmet — track along the banks in a cloud of exhaust fumes and dust devils. The scars of this tragedy, like the signs that fill the universe of the canal, are mute without the interposition of language. This dramatic excursion, imaged here as a mirage, suggests that when something is missing, language speaks. The play of presence and absence is mirrored here in the alternating passages of image and text.

my uncle jumped a freighter on the canal

during the war. he became a merchant marine

at age 15. when he returned years later he

was a communist.

— from “Canal” by Richard Kerr

After a long and beautiful section taken up with the passing hulls of ships, rendered in close-up like a vast and floating abstract canvas, this final intertitle appears. The filmmaker’s return follows his uncle’s, and the passing ships are emblems for all the roads that do not lead to Rome. Walter Benjamin wrote that there are two kinds of storytellers — one who relates the stories of their surround, the other a wandering tale maker, passing stories from one place to another. The boat’s cargo is filled with a foreign lore, sites of conversion that could turn uncles into communists or grouse hunters into filmmakers.

Kerr spent the next three years making On Land Over Water (Six Stories) (60 min 1984), a complex meditation on innocence and experience. The film’s six stories cast the allusive presence of its narrator through an episodic cycle of birth, labour, drugs, and death. Its delicately staged polarities of country and city, female and male, speaking and reading interrogate male mythos in a shattered form of biography. Shifting points of view draw the male protagonist from life’s beginnings to its end, from a native community in labour to a drowning death in northern Ontario. Each section or story is prefaced with a title — like so many title pages in a volume of short stories.

The first of six stories is entitled Indian Camp — a double-tracked revision of Hemingway’s In Our Time. A voice-over dramatically recounts the story of a white doctor’s son accompanying his father to a Caesarean birth and paternal suicide inside a reservation while the screen selectively displays portions of the written text. If this strategy of doubling the text initially works to underscore the reading’s dramatic effect, it slowly takes up a position of independence, allowing the text and its speaking to sing in a fugue of call and response. In this meeting of innocence and experience, two men raise blades to different ends. The first is turned upon a woman, whose jackknife caesarean impels a child to his birth. The second, wielded by the woman’s husband, is turned against himself in suicidal witness, his last breath making way for the boy’s first.

The fifth “story” is His Romantic Movement, which takes to the road, down to the Florida Keys in a post-adolescent idyll of booze, drugs, and tattoos. The most impressionistic of all six stories, HRM wanders through parking lots, carnivals, and diving docks before its closing title “Romantic Movement” lifts slowly through the frame lines. It is centered loosely around the meetings of two scarved vagabonds who are photographed as wall shadows, “shady characters.” They mime the gestures of an adolescent fraternity, drinking, toking, and shooting speed. This coastal tale has taken them to the frontiers of home in a slow drive to oblivion cloaked with the routines of excess. The final title floats like an epitaph for the receding vision of Sparta — for a fraternal unity forged at the expense of Others.

The concluding chapter of Six Stories is also the longest, occupying a third of On Land‘s sixty minutes. Its setting, as the title suggests, is a Northern Ontario cottage, where a woman looks through a break in the tree line over an expanse of loading dock, lakeshore, and pine before being rejoined by her daughter. At Her Cottage is framed by two shots on land, where she recites the same story of her lost husband. Jack was a part-time alcoholic, studying medicine. His restless nerve breaks up the sheltered confines of her community, once driving himself and a friend beyond the lake’s thin ice and into the water below. Like the lone woman driver in Kerr’s next film The Last Days of Contrition, she has survived a man-made violence only to be left with the burden of telling the story of his absence, his failure, his romantic movement — his story.

While shooting Six Stories through the Florida Keys and American midwest, Kerr made a single photograph depicting an abandoned trailer-home with a tattered American flag blowing alongside. Four years later this photograph has expanded to include the post-apocalyptic landscape of The Last Days of Contrition (35 min 1988). His first black and white film in nine years, Contrition enters into an American wilderness to lament the marriage of democracy at home and militarism abroad. Both have returned to America: the political dissenters to address crowds wandering in search of lost ideals, and military trains that continue to bear a technology that seeks an enemy yet to be identified. The airplanes, tanks, and turrets that sound throughout Contrition’s spare tracks finally explode in apocalyptic fury in the film’s closing minutes — signaling the triumph of a technological consciousness, of a will to power bent on its infinite replication, of “pure war.” Kerr here reverses biblical typology, its three-headed themes of exile, wandering, and promised land turned to a bitter reprisal of the separation of powers that have finally cut themselves loose from the population altogether. The endgame is over. The only possible return is a funerary catalogue of what was once possible. In the years after the making of Six Stories, Kerr has undergone an exile of his own, taking up a teaching post at the University of Regina and so becoming one of Saskatchewan’s only experimental filmmakers. It is from this position as a double outsider — estranged both from the Canadian community that nurtured his first works and the America of his early childhood — that he has issued his most overtly political film to date.

Contrition begins with a series of 360-degree pans, lifting the flat lying rocks of the American Badlands in a gesture of attention that recalls the raised lion statues of Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin. The soundtrack is lifted from Ernest Hemingway’s Poem for Mary, voiced over radio by its author who speaks about the perils of political consent, that there is no way to enter a war (no matter how distant) without bringing it home, that there is no place that is not home. This lone voice sounding in the wilderness alternately damns and declares: “You don’t need to repeat this. There is not any ceremony any more. Everyone is gone. You’re alone at the time and the time now is always. Always was a word you used in promises. It is valueless.” In Blake’s words: “They became what they beheld.”

The second of four speeches that move Contrition to its apocalyptic finish is an announcement of candidacy. Narrated over the vast emptied screen of a drive-in theatre, the politician claims his candidacy at “this memorial to the soldiers of Vietnam.” He asks that Vietnam be remembered not only as a passing state of imperial slaughter but as a state of mind, the fifty-third state. The third narrator rhymes the two preceding in the most eloquent sequence in Kerr’s oeuvre. Set against the great emptied expanse of Buffalo’s War Memorial Stadium, the speaker decries the broken promises of America, its constitutional betrayals, in a sensual and measured speech punctuated with the sound of baseball meeting bat, amplified here to suggest its affinity with gun shots. As the cumulus trails part slowly overhead, light fixes the corridors of this cathedral in a ruined stare, its emptied seats a testament to the passing of a society of spectacle. As the speaker enjoins the fascist consensus of Nazi Germany and post WWII America, a batsman appears swatting imaginary flies, lost in the rules of a sport whose warlike analogies are tempered by nostalgia for the game pastimes of America’s youth. In 1870 Emerson writes about those “amiable boys, who had never encountered any rougher play than a baseball match.” The speaker seems to ask: “Will you play ball with America?” Kerr closes this sequence with an evocation of the flag raising at Iwa Jima, three uniformed attendants struggling with the wind-worn drape of America while a male choir sings “The Star Spangled Banner.”

The flag waves throughout, recalling its status as national projection screen, its stars recalling those more usually seen in heaven, its wavering evanescence made to bear the ideals of a history that has finally abandoned the possibility of union. This all leads Kerr to a disembodied telling, to the presentation of a succession of bodiless voices howling through a geography left behind in “civilization’s” inexorable movement westwards.