Notes on 3 short movies by Dani Leventhal as if I was Dani by Mike Hoolboom (2012)

written for Hallwalls Gallery Catalogue, fall 2012

The camera runs out of my mouth and onto the page, and then her shoulder blades, and the place between them where the secrets are buried. Like everyone, she’s showing me what she doesn’t want to show, she’s telling me what she doesn’t want to say. But she can’t help it. The words are falling out of her, and she hears them from one direction, according to the unsilvered mirror of her imagination. And my camera hears them the other way, as the place where the unspoken can find a home. Sometimes I don’t hear the words that way either, it’s not until later, when I’m back home, when I’m back watching the yields in my computer, that I can see what the camera has noticed. Again and again.

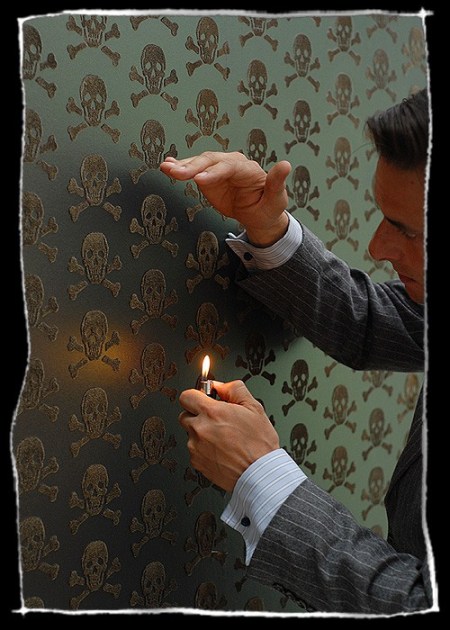

The camera is not a part of me, it’s part of what’s around me and I follow it around, I let it take me there. I’m not walking my dog. I’m not giving instructions to my dog telling it how to behave. Sit. Heel. Roll over. Eat. Instead, my dog is showing me how to walk in the neighbourhood. How to live inside a world that is not filled with road signs past and future. The camera brings a rectangle so that intentions can flow inside it. The sound comes from everywhere at once, but the picture of the world happens in the rectangle. Mostly in close-up. My camera likes to get close. Sometimes it’s an extension of my body and sometimes it’s an extension of her body, or a house, or a bird. When it’s turned on, as the saying used to go, it is part of whatever is going on. Maybe that’s what being turned on means. The camera turns on, and then I turn on. Or at least I turn. The camera allows me to turn towards the subject until it’s not the subject, it’s not over there while I’m over here. The camera touches something about loneliness here.

And then you go back over the pictures and sounds when it’s time to edit. You try on the second hand clothes. I’ll second that emotion. You listen to the second thoughts. You go back over it all again. You pick out the moments that are shining and bright and you put them next to each other, and because they’re made with the same kind of closeness, or the same kind of distance, or the same kind of listening, they belong together and they don’t belong together. They create a space, some new kind of space, and that’s where the viewer can enter. The way the pictures come together makes a door, or a series of doors, and that’s where the audience walks in. If they want to.

Notes on 4 movies by Dani Leventhal

Dani and I had begun to write just a few words, the usual welcome mats of the English language, the learned hellos, and then I was granted the rare chance to show off her movie at the honcho festival in Rotterdam. It’s a masterpiece I won’t write about here, her half hour Draft 9 (28 minutes 2003) which already contains a lifetime of looking. Perhaps several lifetimes. Is it because I am always so busy shirking the moment that I find a particular happiness in her movies, which are always bruised and dirty and up close to everything? Lacking any means at all, she finds the appropriate distance to her subject, and that distance turns out, in most cases, to be not much distance at all. And it’s not just a matter of her camera, but her open face and hands and the heart following surely right along. Her heart is forever busy jumping up into the light.

When Dani’s movie hit the screen in Rotterdam I could feel the room change. It was a serious crowd, there were professionals there, the ones who had seen it all, the ones who’d written the books, climbed the mountain and brought back the tablets, those kind of folks, but when her movie started everything stopped but the pictures. They are difficult and bloodied, and proceed in a crashing collision of instants one after another, yes of course of course it’s all too much, it’s always been too much. But here at last was a room thinking as fast as she was cutting, jumping every jump, joining every disjoint, who could see as fast as she could live inside her camera.

It’s just me I know, because I happened to be there, looking out from the small hole of my personality, but I felt that an artist was born that day, if being born meant recognition. The other cut of ‘artist’ happened a long time ago, when Dani got kicked by her first horse or stuck her face into a pig’s face or who knows when. A long time before she ever picked up a camera that’s for sure. She already had a body trained and opened up for looking, and when she got hold of a camera she just kept on looking, only this time there would be a record, a mark. She used her camera to go further, it was her mirror in the labyrinth, now there was nothing she couldn’t face. Right?

Imagine my surprise a year after Rotterdam when a disc arrives in the mail from Dani with some hard scrawled charcoal drawings and on this disc four new movies made in 2007. Four! Of course the DVD is filled with sound that is distorted and too loud or way too quiet, and there are glitches and bits which won’t play, but through the technical maladies it’s all still there, the same heady jam that made Draft 9 such a whirl.

Some thoughts.

When Show and Tell in the Land of Milk and Honey (12.5 minutes 2007) opens I see a bee on a flower so close that I am also a bee, the camera hovering and swaying, blowing like the flowering stalks. Isn’t she worried about being stung? Or perhaps these are the pictures which arrive after the bees have already landed and sunk their poisoned spears and flown off. But nothing deters her, she stays close, so very close. I am one of them now, because of her old magician’s trick, she turns her camera and then her audience into bees.

Against a yellowed stain of a background a woman speaks about giving birth. She is double voiced, so it’s hard to make out exactly, words and phrases emerge from the scrum. The way these words arrive, the issue of language, this is also labour. The site of production. Language doubles and redoubles, circles round itself. The opening scene is also the primal scene, the unbearable beginning: the bees transfer pollen grains to flowers so that more flowers can grow. Then a voice speaks of birth in a fall into language.

A woman busy licking between the thighs of another woman, the sounds of an animal, the huge hanging tits of a Scottish Highlander. It strolls right up to the camera and Dani says, “Hello,” in a high voice and the horned beast gives her a head butt. The picture vanishes. Can video be as bruised and run over and beat up as a body? It can. It must be.

The subject looks back, the picture that touches, the cost of being so close, of intimacy which in Dani’s world is also and always an animal gesture, an animal closeness. As close as an animal, as close to our own meat and gristle as an animal.

A couple of kids play cards and the light glows around a shirtless body, he laughs and lays down another card as the camera stays down low. This is the rarest of all the abilities that Dani has—she is able to turn the camera on while life around her happens. Nothing stops or waits or freezes, everything is in motion and she is in the middle of this bruised, laughing fragment, looking up into the light. A German child draws a missile . And then Dani’s large face looms into the lens. “I was raised to believe that Israel was the land of milk and honey.” She winds up on a farm on a kubbutz where 2000 eggs a day roll off the conveyer belt and she is charged, along with some others, with spraying the eggs with bleach. (And collecting the sick hens to sell to the Arabs across the fence) After a stint at the metal factory where she was sexually harassed.

A night train pulls in, her grandmother offers her ice cream in a gallery filled with hanging screens and moving pictures. “There’s a suicide bomber over there,” Dani says and then takes a bite of ice cream. They are killing my neighbor’s children and the ice cream still tastes good. They are destroying my corner store but when I buy my ice cream from the other corner store, the ice cream still tastes good. The Others, the Palestinians, the ones displaced and segregated, robbed of their own land and shunted into poverty and deprivation, all this suffering appears on screens, constantly playing, permanently on display and therefore invisible. “You get used to it.” You eat ice cream and this turns the pictures off. It’s a trick, an old magician’s trick. All of my seeing is in my mouth. And my mouth tastes good.

A woman rescues a pumpkin from a swamp. Dani takes frozen dead birds out of a bag and fondles them. Their feathers blowing in the wind makes them seem alive. From a distance you can hardly tell, until you get up close. And she is always close. Her feet are dirty, her hands filled with bird death. The cat cries. Tarot cards are shuffled. The future, anyone?

A Puerto Rican man on a bus, the camera pushed right up into his face, talks about lizards biting his ears and hanging from his lobes all day when he used to go to school. He is also close with the animals. Why isn’t she scared? Why is she so close, close enough to be hurt by his bad looking laughter which could turn into something else when the bottle runs out.

Finally we are in a bar looking oh so very clean and antiseptic. It changes colour like a mood ring, it is pink and blue and then pink again. Dani is the lonely occupant, waiting at her table. Back in the city, in a designed space, everything clean and orderly and perfect. In other words, no happiness. The camera is not close here, it looks at it all from a distance so that it can gauge the effect of this geometry on the ‘subject,’ the maker of course, it is always the maker who is at stake here. She is always dragging us along, pushing us into the face of strangers, party to another chance encounter.

In the closing scene we see a woman on a tight rope, falling off. The bees make honey but cannot eat it. You want to see a nursing cow and it hits you in the head. And the woman between your legs? The child that comes from that place? The stranger on the bus? For a few moments there are gestures toward child’s play, flights of reverie with the birds, only the birds are all dead now. Now it is time to take up again with the monsters who are still alive, and I among them, dirtied and crushing you, and stepping on your hope without even noticing.

Litau (7.5 minutes 2007) opens with a dance number: is it a foxtrot or a samba, at any rate, it is one of those body shaking rhythm numbers that have left words behind. Three figures move together, lensed up close in swaths of brightly coloured fabric. It might be a her between two hims, there are no faces so it’s hard to tell, might be she’s wearing the pants today, might be he’s got on his best hose and heels.

Meanwhile on the street, near the dirtiest and most beautiful windshield in all of Estonia, Dani listens to a woman talk and scribbles down words like Puha Vaim next to a child’s face. “Or you go to hell, oh I understand. That’s why you’re willing to spend time with me right now,” says Dani. One thing is for sure: this is not an interview like those which may be found in a score of other doc manoeuvers. For one thing, despite the woman’s underlinings and rhetorical repeatings, it is clear that not so much is clear. Between them stretch a lifetime of mysterious experiences. After all that, how can I know you, how can I find you? Could it be here, on the rusted hood of this abandoned car, is this the place where we could make our stand together?

Dani’s journal offers up another face, a star of David, a fire. They are the quickest of sketches, Dani is turning these unknown words (are they a prophecy, a warning?) into these small pictograms so they might be stored and saved and rescued from the present. They are both people of the book after all, it lives inside each of them as a text waiting to be recited. Signs are inscribed in her notebook so she can carry them away. And us alongside.

At this moment the camera tilts and a young girl in a polka dot dress spins round and comes to a stop, and then again and again in the other direction. Smiling. The woman keeps smiling, she is the one writing enigmas into Dani’s notebooks, reciting foreign words. A minute into the scene the camera shifts again and the talker’s face comes into view, it turns out she is a double-chinned, grey haired lady with a broad round face that narrows suddenly and precipitously into mouth and chin, as if their maker had run out of time or material.

A young girl colours a rocket yellow in silence. The mysterious words, pointed, emphatic, underlined, hang over this scene somehow, the way an impression of a room remains if you turn the lights on for a moment and then off. The phantom of a room remains for a moment. And then it too gives way.

A young boy in a bathing suit leans out on a rock, speaking to another boy crouching in the water below. Their mouths are turned away from us, turned towards each other. Unlike the usual cinema, whose inhabitants are always opened, on display, always ‘turned out’ to offer their audience the best view, the best seat in the house, here the views are partial, the codes only partially revealed, what is most often on view, again and again in this tape, is the way others remain a mystery.

Two young boys listen to a radio in a parking lot. “It’s shit,” says one. “I like it,” Dani responds, which prompts the beautiful young one onscreen to curl his lips into an O and dance up and down. It takes about twenty seconds.

A young girl in a red dress climbs an apple tree. Three seconds. (Dani writes me about this scene: In this clip the boy who turned his lips into a vowel and hoots like an ape is the voice-over for the girl in the tree who is now an ape because of his voice-over.)

A Latvian soldier checks documents on a bus. The camera is low and unobtrusive, but right there in front of him. What if he notices? Will he look up and see her, and see us watching behind her? The threat of being seen, of being looked at in the wrong way by the wrong person. Ten seconds.

Two boys look into the guts of a car. One of them shirtless and lean, both of them blonde and too young to know any better. A girl smiles shyly behind them. She knows everything but lacks the agency to act, caught inside her gender trap. Action is left to the unselfconscious and unaware, the know-nothings. They gesture to something beyond the field of vision speaking in Lithuanian. Ten seconds.

Two children describe a soft shell crab encounter in German. “Was it alive before?” asks Dani. They never answer.

A woman lying by a river. Or dead. Or asleep. Pink top, brown pants, black rubber boots. Dead or alive, she is also part of the natural world.

A walk down a stairway with carefully close attention paid to the wooden banister, the camera follows its turning and twisting downwards. For some a road of yellow bricks, for others a wooden hand rail is enough.

Horses watery and close. Soft-eyed, they graze each other. Their soft touch is also a look.

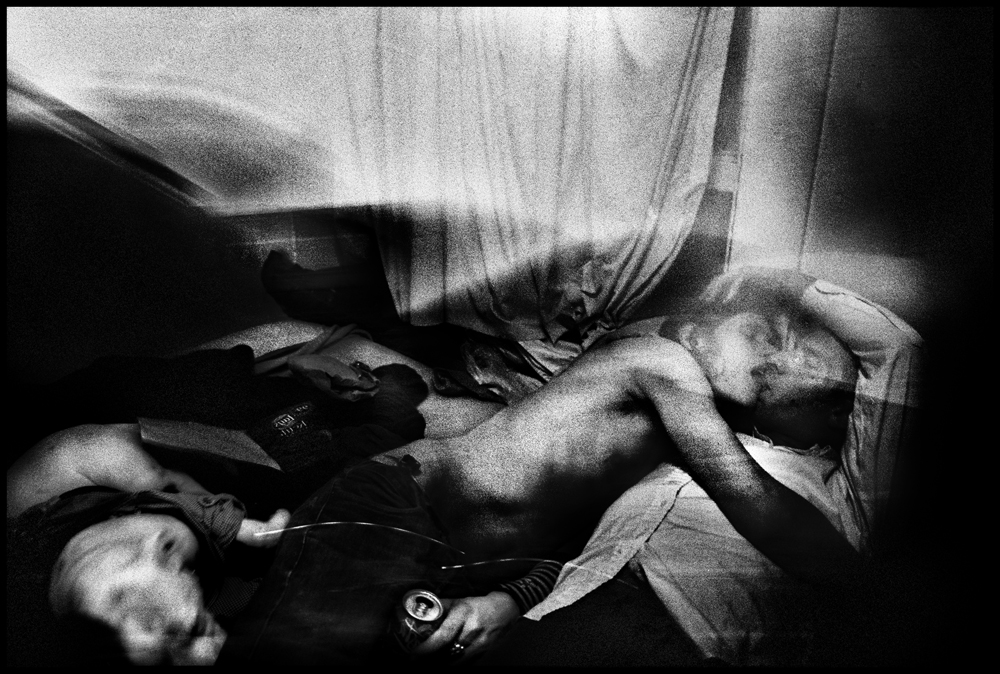

A woman lies in bed, the camera pans over her in a post (pre?) coital haze. She is seen with the softest possible eyes. The eyes of a horse, for instance.

A football match on TV. (Could this also be love?)

Street musicians stroke their violins and cellos while Dani’s camera returns to the car seen at the tape’s beginning. The woman with two faces, large and small, has picked up her child, the one who turned and turned. They white out and the movie is over.

Litau is a prayer of moments, of tender strangers met in passing, but met full on. There is no holding back or opportunity for rest. She has made a composition using fragments of incomprehension. Litau refuses to wrap up all these encounters into a story, or pretend they are part of a single gesture. Instead we are offered the raw, unremembered stuff of living. Dani is always in the midst, pushing her face up close, trying to find a way to get through the scar of language which names and separates, which binds and heals, like the spine of a book opening and closing.

9 Minutes of Kaunaus (6 minutes 2007) the title says but the tape is only six minutes long. The other third has been shorn away, left to the imagination as a promissory note. In a Lithuanian synagogue young Domas Darguzs whispers his wide-eyed truths to Dani. His miraculous confession informs her that this place was made of materials belonging to ancient Egypt, and that world peace will arrive when we can look on with love at the art of living that stands before us as statues. “Awesome,” Dani answers and he replies, “Yes it is.” Wherever her subjects are, this is where Dani is. She meets them over and again, whether child or bird or insect or holocaust survivor.

In between his testimonials from the other side are moments from a goat farm. The goats suckle on artificial nipples protruding from a nipple tub, or in another protracted scene they are attached to milking machines. The udders well and secrete milk like an ejaculating penis, again and again, caught in the infernal cycle of production.

Fire snakes from Egypt, gold discoveries and the mystery of death all pour of Domas’s mouth. One image gives way to the next in rapid succession like one of Dani’s tapes. His pictures are made with words, issuing from the space between his first set of teeth, and the small shifts of focus which allows his face to enter the frame at a speed which permits us to receive him. Like oracles past his orations are casually transcendent, it is a sermon delivered not from the front but the very back row, where all the buried and forgotten truths may be met again by anyone young or innocent or animal enough to receive them.

3 Parts for Today (12.5 minutes 2007). There is something about a bird lying on the ground that doesn’t look relaxed or at ease. It lies there in a cascade of grey and white feathers, heaving with breath, the yellow bill opening wide and all I can think is: how awful, how wounded. And how beautiful. It must have hit that harsh brick wall and fallen here, in the last beautiful light where Dani (does she ever sleep?) has found her.

Yonatan Shapira (named in the opening title as “The Refusenik”) talks about joining the Israeli army after the first Gulf War and becoming a helicopter pilot.

Grandma Leventhal is lensed centimeters away from her left elbow, the camera pointed straight up into a wattle of neck and the sagging flesh of her arms. She takes a pill and then a cracker. “I just don’t know why the pill doesn’t go down without you tasting it?” Dani asks/says. How can experience be masked, buried, repressed? Are we in the land of metaphor here? The denial of even the most rudimentary rights for Palestinians is somehow equivalent to a pill swallowed by Dani’s grandmother whose taste (or reality) is covered over by a cracker. Here is a politics searched for and unearthed and returned to again and again on home turf; in pictures of home, friends and familiars. The problem, the difficulties are never “out there,” but also and most importantly “over here.” How to find the necessary distance or closeness with the camera in order to be able to find them?

From a television screen a documentary fragment once again shows Yonatan Shapira speaking Hebrew, though the clip is silent (and shot home movie style, in what looks like someone’s living room where he speaks in front of a small group of folks) yellow subtitles permit language to be applied. “And then a little seven year old girl started running towards us. On one hand I saw this little scared girl… maybe she’s going to explode… I shouted but she didn’t stop…”

Incredibly at that moment a young girl gets up and walks by Yonatan. He can only smile and shake his head. “Yeah that girl was just about that high… but then I shot a warning shot in the air, the girl froze like this, for me it was like being hit by hammer on the head. For months afterwards I couldn’t forget that moment, and then I told my commanders I’m not doing this anymore.”

A blank post (or is it a chimney, a tower?) with a frayed red rope attached stands tall, the rope so hardly there by the time it reaches the far end of the frame that it seems to hover miraculously in the wind. The camera tilts to reveal it is the stem of a windmill.

Yonatan returns and contrasts the exhilarating lift off of his helicopter with the devastating effect these military machines bring to their target.

All at once we are offered experiences soft and hard. Raw and cooked. Dani feels along the seam of the real until these moments of contradiction erupt.

She films her father in temple singing with his eyes closed, softly chewing. The word “peace” passes through the air and some guitar and then there is some shuffling of hymnal pages. Isn’t this word already a question? How can there be peace in the synagogue when this religion has been used to bludgeon and displace an entire Arab population?

Then Dani appears out of doors in jeans and a hoodie brandishing a bowl of muesli and fruit which settles into the middle of the frame. She talks but we don’t see her face at first, her words and mouth are off screen. (Some illusory wholeness, some easy place of seeing and knowing is endlessly deferred or troubled.)

“There is a Jewish law that says that you shouldn’t eat alone. I just had a meeting with Yonatan Shapira, and here is this activist, a Combatant For Peace, and it was so funny because I showed him this video that I made of him, of the lecture that he gave, and I have mixed the footage of him being a helicopter pilot with this bird. I have footage of this bird that had just fallen, a little fledgling, and he was like ‘Did you give it some water? What did you do?’ It didn’t even occur to me to try to save that bird. It was just this beautiful footage.”

A woman wrapped in a gold mylar sheet makes her way towards the Ignalina nuclear power plant in the distance. End of part one.

Part two opens with a set of titles.

Antje Muller’s grandpa was a Nazi. One night we went out dancing with my friend Unis, a Turk. He knew I wanted Antje and he hit on her right in front of me.

A woman in red calls out of a megaphone, bikes park near the windmill. A picnic of bread and strawberry jam ensues. At an amusement park mechanical camels race across their prescribed tracks, digitally slowed. A woman in a red dress walks gingerly along rocks in water. A pair of hands knit red yarn against a luminous red cloth background. Dani and a handsome man and a woman under a blanket on the beach. There is laughter and music, the shutter speed is slowed, the pictures blurry and intense. He speaks German and Dani is so close, their feet are far away and a horizon of Black Sea just beyond them but the faces are close, the touch of the blanket fills the frame.

The woman lying there face down, never saying a word, somehow between ‘them,’ the man speaking German and Dani’s playful accusations. Wait, wait. Is this woman the ‘Antje’ mentioned in the titles? Dani laughs to cover over her bad feelings (why do women do this so well, so often?) but it’s clear she’s hurt. Why is she hurt? I grope backwards across the line of pictures and find myself looking again at those intertitled words (“Antje’s Muller’s grandpa was a Nazi”) and especially the words she uses for love. “Hit on her.” To have the beloved taken away, seized, to have one’s hope stepped on so that another’s might hold sway, all this is “hit on her,” taking a hit. Where to turn after this beach, why is there room under that blanket only for two? Dani records an enormous tree with a deep scar running along its length. I am this tree, this body of water, this unspeaking woman. Love is a hit.

Part 3

The voice of Steve Reinke erupts over pictures of a kosher Schawarma stall, and then two Canadian geese duck their heads into water in perfect time, turning around some unseen centre. Steve speaks a text of Dani’s and it is delivered casually, or at least its laughing interruptions, its abrupt stop and starts, give it the impression of verité. He talks about meeting Shapira, the Refusenik, and then about prayer, the gods that live outside and in.

“The difference is that I’m no longer praying to an outside force, a force which reinforces my own insignificance. Instead I’m looking inside and the inside is always there. It’s there 24/7. This other God outside sometimes doesn’t seem to be there, sometimes seems to have receded into the distance or listening or not listening. But the one on the inside you can feel it and see it in other things it’s just always there. So I can call on it, I can remember it. It gives no reason to escape into instant gratification of sex or booze and then the rebound from these things which is a kind of loneliness or emptiness.”

The two birds fuck, that doesn’t take long, both raising their necks alternately as if in triumph or release. And then they are back to ducking their heads under the water and using their bills to send water running down their backs. Like so many other pictures that Dani collects, they are so beautiful. They are also the end.

Yonatan Shapira’s refusenik remonstrations are interwoven with moments of Dani’s family (her grandmother and the pill, her father singing), her broken love in part two, and finally a sort of reconciliation (God is inside) while the geese fuck and bathe and swim right on.

So now of course I am waiting for more. It’s enough for now, I’ve seen these movies and re-seen them. They are humming right along to the same tune that delivered Draft 9, so muscular and fearless and camera ready. Now I want more, at least enough to fill the granaries, the distribution houses, the screens of festivals in years to come. Let it rain. Let it all come down.

I am the Cracker (2009)

Published in catalogue for Hallwalls Gallery, Fall 2012

My cousin Janie liked to come over and smoke meth in a bright blue pipe she named “Shirley” for reasons we were too young to ask about because she was our babysitter. Our meaning my brother and I. After she smoked up in the garage, she would come in with her face all waxy and loose, like you could pry the whole surface off with a good set of nippers. She would stow Shirley in a bag we were certain she would leave behind but she never did, and then heat up a big bowl of wieners and macaroni. A personal favourite. When she had boiled most of the water off and the weiner flesh was so loose it would fall apart if you touched it, she would slide it onto plates we held out for her inspection. She would fork up hardly there fragments which she allowed to dissolve in her mouth while we would get as close to her as we possibly could, imagining as we did that we too were getting a little puffed up. She would tell us lawyer jokes or else graveyard jokes or else bartender jokes we didn’t understand. “Two drunk guys walk into a bar… you’d think they’d see it coming.” “A man walks in to a bar with a piece of tarmac under his arm and says, “A pint please and one for the road.” Although usually she was laughing so hard before she hit the punch line that they never really came out right and we ate up every second. When she wasn’t telling us jokes she never quite finished, she told us how most people didn’t have faces. They had what she called “borrowed features” or “borrowed expressions” and nothing of themselves at all up there where everyone could see it. Although sometimes you could look behind these faceless faces and see something else trying to poke through and my brother and I practiced that a lot, mostly with each other, staring intently into each other’s quiet imperfections until mother would come home and ask us just why were we sitting around with nothing in our hands all the time?

We worshipped our cousin Janie, and even when she moved away I knew that I wanted to be a meth addict when I grew up. It was something to believe in, a credo that rang well past the occasional flag waving and Sunday schools that were offered up as conviction receptacles. But I lacked the talent for addiction, I just couldn’t seem to keep my mind quiet long enough to allow compulsion to really take hold, so I had to settle, like many of my friends, for binging on other people’s problems. Whenever I get worn down by best friend Dale (two divorces, three miscarriages, one breast cancer successfully treated), I turn to the comforts of the internet, particularly the glorious www.fmylife.com. If you haven’t already posted, it’s a website where users anonymously post reasons why their life sucks right now.

Today, my girlfriend dumped me saying she wanted someone more like her ‘Edward.’ I asked her who Edward was. She held up a copy of her ‘Twilight’ book. She was talking about a fictional vampire.

Today, I was passing a building and saw a fat, ugly person inside. I started to laugh and noticed it was my reflection.

Today, as my boyfriend was trying to convince me that he was not having an affair with another woman named Julie, he looked me in the eye and exclaimed, “I would never cheat on you. I love you more than anything, Julie.”

Today, I fell asleep. I felt something on my face and batted it away. It was my hamster. It died from a concussion after hitting the wall.

You see what I mean? There is nothing quite as satisfying as someone else’s misery. But even through the borrowed feelings and Dale’s larger-than-life problems which seem to be designed by some out-of-work Soviet chess grandmaster, I am still haunted by Janie’s simple affirmation: that most people she met didn’t have a face.

If this were a movie there would be a title reading Ten Years Later, and someone watching it, with or without a face, would turn to their best friend and open their mouth wide and thrust their two longest fingers in and out of it. The universal hand signal for: this really chokes.

Dani had a face that didn’t belong to her. Not at first, not at the beginning. But when I see her now, today, on the Friday she’s come into town for the first time, I can see that her face is beginning to settle into her. This accommodation and return, like most homecomings, is producing in her a kind of shock. Oh god, is that me? She walks through these streets with eyes so wide she’ll be able to sketch it out later, when she’s by herself, squatting in the unrented corner of the Howard Johnson’s with her charcoals and the bad paper she prefers because you can make mistakes. Finally alone, she’ll lay down the name of each and every store and face and hydrant we passed and recognize it as a block she might one day sign as a return address home. That’s when it becomes her city, the streets she opens to and admits and allows to live on inside. Somehow, the knack of being a tourist escapes her.

A passing friend of a friend stops with a manchild on four wheels, unsteady in the snow, his listing pre-verbal face drawn instantly to the place where Dani’s face would be if she had one, if she hadn’t refused that somehow. His arms are bent double and apparently helpless, but he is looking so very keenly while his two-legged chauffeur or minder or boss is busy wearing the mask of friendship with the other woman in our entourage who I can’t speak about, all in the great blind spot of the world behind him. Behind us all.

This is how it works, the man in the wheelchair might be saying, if his look could be cashed in for words. I am helpless, and in my helplessness and need I will teach you how to look after me, and by looking after me, to look after yourself. Who could ever be so strong to be so weak? He was busy leaving this wordless question for Dani before his confederate rolls him back onto the eastgoing lane while Dani leads us in the other direction, offering an equal and opposite reaction, matching, without even needing to look back and make sure, the speed of the little metal wheels that reach out for every bump and trough and uneven concrete pour on the sidewalk still unrecovered from last night’s snowy dump. Dani’s feet fall into the rhythm and we fall in right behind her. Her globalized sneakerware and his pre-motorized two-wheeled chariot locked up together. She looks up at me as if to say, “Do you understand?” and I nod, not catching anything she’s throwing, but not wanting to stop and have her break down the whole drill, hoping instead that she’ll just show me again and again.

Finally we arrive at the worst-looking Korean restaurant in an area of the city dedicated to Korean restaurants on a tip from a sitter who has chowed out at each and every one and proclaimed this the very finest, no question. The television plays the news from three or four weeks ago, all in Korean with English subtitles, and both of us are finding this more comforting than we really want to admit. Everything else on the tube has re-runs, why not the news? We hardly know each other, Dani and I, but two hours ago she brought up her folks to shake hands. It’s that kind of city. No kiss kiss. Embraces are strictly for East Europeans that still have bodies. Warm clasps, forehead touchings, all that is forbidden here. We are masters of distance. We like to weigh in and measure up and then refuse. Besides, here in Toronto, most of the year is winter, so we all have to wear clothes on top of our clothes until we stop having bodies. So even though Dani and I hug on the walk — and she out of her three-layer polydermal weatherproofing already because she’s been upstairs waiting — I am still held up inside a small men’s room of fashion accessories all worn at the same time in order to stop my body from feeling what it’s really like outside. And then to stop what it’s feeling inside. Oh please god not that. And not you. So when we embrace it’s more like the idea of an embrace, and when I meet her parents they seem more like the idea of Dani’s parents, though I make requisite genetic checks and see that at least the one who calls herself mother wears a resemblance up where strangers can see it. Dad looks like the genetic road not taken with his It’s-OK-I’ll-Wait chin and his stately forehead the very opposite of Dani’s head-on collision of a face which is only now arriving after how many crucial and incidental and already forgotten fallings in and out of love. Father must have dropped in after the crucial ejaculation, so it’s as if he’s wrapped in a layer of winter wear as well. Her parents vanish after our introductions, leaving us to walk slowly towards the worst-looking Korean restaurant on the strip, hidden behind come-ons for discount sunshades and an army of begrimed nail clippers. Dani tells me that she knows exactly what she’s going to look like at every age, because that’s what her mother looked like. I don’t ask her if this is a good thing or bad.

The light flickers through the bad blinds as if it’s unsure whether to stay or go, stretching our shadows across the table until they’re almost touching, leaving us to wait with our ordinary hopes. The whitest man in the city sits two booths behind us and complains in a whisper to no one at all that the menu is only in English, and that he can’t connect a word of it to the best year his stomach ever had when he was teaching in Pusan. The vinaigrette pucks arrive and I push the kimchi to the other side of the table where it can trouble someone else’s conscience. I begin to worry then, as I always worry, whenever artists are gathered, particularly those of us dedicated to small scale reversions of television, that our chatter will degenerate into shopworn talk, insider tales of software glitches and platform failures which will lead, quickly and inevitably, to disappointments of a more personal nature, as a parade of critics and starmakers (who would be identified only by initials because their full identities are beneath and above mention) had passed over our genius pictures which must have appeared to them like the forbidden and unwatchable face in the labyrinth. No doubt they feared their audiences might be turned, if not to stone, then at least to wondering why, if our righteous upper shelf confections could be had, then why did they have to put up with the horizon of ordinariness that typically passed for museum distractions?

Instead, I spoon up a jellied tendril while Dani talks about the ice queen who followed every nerve root down to its tender origins and then began a pulping and shredding exercise which she served up to both of them as heart muscle gumbo before splitting. Her last girlfriend. Only she doesn’t say the word ‘vampire,’ she says, “I was selfish, so she left.” She cuts her words off like that and leaves them on the table where they stare back at us in accusation. While we wait together in a silence she is no hurry to let go of, I watch the place her face should be twist up into a terrible knot of pain. Could you please move your truck off my foot? There is a moment that sits atop her perfectly symmetrically shoulders which should be shield and ground cover, but instead, it never stops opening, and I can see how much it hurts and how she doesn’t mind that hurt, or maybe she’s grown used to it, or perhaps it hurts more if she doesn’t let it crawl all over her, if she refuses; so she keeps pushing that soft open place up into the hands of strangers. Like her ex-girlfriend Anja for instance. Or the man without legs.

The television shows Israeli Likud leader Benjamin Netanyahu: “You cannot say both Israel and Hamas are symmetrically to blame. They’re not. One side is to blame, the side that targets civilians and hides behind civilians. That’s Hamas. The other side represents the rest of humanity. Now choose.”

When Dani met Anja from Europe for the first time it wasn’t contact narrative interspecies genocide but it had its shaky moments. Anja would spray language out of her mouth, and occasionally out of other, more unlikely places, at every possible inconvenient moment though mostly she said nothing at all. Try to touch her, though, and the words ran, one kiss and forget about it, the whole evening became alphabetic shambles. She was, Dani thought, so very like the dolls that always appeared around Christmas time with that soft, almost-flesh, which Dani longed to layer over her own skin, and that secretly admitted (Where was it? Where?) a satisfyingly depressable moment that would beg for her squeezing, choking, grasping hands that were learning how to perform their hand-like duties on models so that one day they might be able to do the very same out there in a world which seemed to belong, at least temporarily, to her mother, and a father who hadn’t left yet, and whose full time preoccupation seemed to be building fences, which he did mostly with words. The clenched doll-in-fist moments provoked results which varied in personal satisfaction from excellent to very very excellent, and no matter how often they were glimpsed as not-yet store bought promises between distracting televisual episodes of unhappy posing screen doubles whose throwaway deliveries were greeted with howls of laughter, or else low-gurgled cheers of hilarity or else scrumfulls of belly-shaking joy delivered by an unseen chorus (perhaps the personal conscience assigned to each televisual avatar?) Dani never imagined, no not once, that the better-than-real-life sister she held in her hands belonged to her alone. This year’s doll, already worn with handling and love and need, would cry out in recognition every time she was squeezed, though this wasn’t as fine as last year’s delivery which was able to shed real tears. How satisfying it was to hold open the hatch and let the cold sink water fill the little-big doll’s cavities until she was overflowing with heartbreak.

“Here I am all dolled up,” says Anja, the dollfaced baby doll, to Dani, in the private part of her kitchen. Everyone is allowed into Anja’s bedroom, but only her intimates are permitted into the kitchen. She is a siren of oral culture, make no mistake, despite her silences, and Dani follows that voice like the old sailors caught between wanting only what they couldn’t have, or wanting only what others couldn’t have. She (Dani) would stagger into her (Anja’s) kitchen with those meathooks pouring out of her shoulders ready to find the place, the unmistakable place in Anja’s body which would at last begin their relationship for real. It wasn’t Anja’s fault that when Dani touched her she either felt nothing at all, or else too much, which meant that more than occasionally she would have orgasms of increasing and frightening intensity which even Dani, parched and jawsore and at home inside intensities of every kind, would want to slowly back away from, only to find Anja, who generally touched back like an indifferent feather shedding from a passing duck, and who hated the very idea of orgasm, was unable to stop herself from riding the wheel right back up again, so she would take hold of fistfuls of Dani’s too-short hair in order to pull her back into the crux of legs and pussy that held her (Dani) red-faced as she (Dani) dissolved the place between the place her face might have been and Anja’s pleasure, that almost-moving, hardly there, shameful spotlight which came and went, but mostly went, except for these few brief disgusting (or so she (Anja) imagined) and violent intrusions which were about the sexiest thing Dani had ever experienced. After they were through, after her (Dani’s) hands were raw and sore and tired, Anja would get up and give herself a thorough washing with a special Pine soap that had already seeped into every corner of every room, yes, even the kitchen, so when you walked into her apartment it was like walking into her body. It was just another thing that drove Dani crazy, which is why she kept suggesting they meet “over there.” She never called it Anja’s apartment, or worse, the kitchen, she just said “there,” or “that” or, if she was being pressed, “you know, the other place,” because the very idea that someone was going to walk into her house-body made Anja quiet and reserved and anxious and she would want to quit whatever conversation she wasn’t having so that she could go and get down with her bitchy unhappy friends who sucked on each other’s complaints like sugar candy pops before anything worse happened. Like having an orgasm for instance. Or worse, half a dozen at decibels that had already worn down the hearing capabilities of her last lover, two professional sound recordists and her uncle.

Dani tells me this as she sips at her peach-coloured tea as if it’s not going to give her stomach-curdling gas which she will fail to exhale because the woman I’m not allowed to talk about is sitting right beside her and couldn’t fail to notice. One cup and then another and then the down home waiter walks up to us almost shyly like he’s going to introduce himself at a party and puts down a fresh pot so we can start all over.

Before Anja became Dani’s girlfriend, she (Anja) knew the gender of everything around her. Tables were girls, chairs boys. Hands belonged to girls even if they belonged to boys. She was from a faraway country called Europe where it was the custom. Dani didn’t believe her at first, particularly the bad turn about not being able to decide for yourself whether the slippers you wore or the orange juice you craved — even though you knew it was made from oranges picked by illegal migrant workers who were paid less than minimum wage to support families at home — why couldn’t you pronounce this juice a him or her by your lonesome? It was as if someone had already tasted the juice and tried on the slippers and left you with more word fences that circled everything. Sometimes, when Anja was in a particularly reclusive mood, which was most of the time, Dani would bring over a catalogue from a store that she would never visit but provided useful nostalgia fodder in those uncertain years when entire weeks were spent in a nostalgic reverie for stores never visited, experiences never shared, romantic power outtages never undergone. They would sit together thumbing through pages while Anja intoned, “Boy” or “Girl” over the unpeopled furniture spreads or throwaway cataloguettes of luxe condo resale units whose furnishings provided the settings for dreams they began having only when they were awake.

Now the television shows Israeli Parliamentary Member (Hadash, Jewish-Arab party) Dov Khenin: “Well, I think that journalists are not allowed into Gaza, in order to not—to not make it possible for people around the world to see whatever is happening. The situation is terrible. You know, the people are doing surgery without, you know, any tools, without anything needed to take care, medically, of people wounded.”

Dani, on the other hand, was American, and so had no need to assign gender roles to every object that stood just outside her reach. The starting blocks of her personality lay not in any adherence to rules which anyway remained invisible to her, but to the simpler act of making choices. She was born with some not-yet-outsourced understanding of what things cost. She had only to cast her eyes on an object and she could see the failed union attempts, the free trade agreements, the child-slave labour, and off-shore Cayman Island accounts which had brought such a necessary consumable to her attention in the first place.

She knows that as an American, her choices define her. Choices look back and claim her, they are the prison in which she finds her freedom. Chocolate not vanilla for instance. Red jelly beans first out of the bag. Then black, green, orange. Yellow always last. Always. Yellow was for trading or on the days when there wasn’t anything else going down except eating the candy you didn’t have time for. And girls first of all, absolutely. If passersby know how to look (and none of them do) they could see her love of girls written plainly on the face she doesn’t have yet. This choice and love and happiness and unhappiness has been steadily changing her face all these years because it took her outside the flow, though she didn’t realize that at the time. All of her important choices, and everyone else’s important choices, are made in exactly the same way. Thinking has nothing to do with it, but it offers her a consolation to imagine that it does. She’s traditional like that, but not about much else as it turns out.

Palestinian (living in Khan Yunis refugee camp) Umm Thaer: “Does anyone evacuate their house that they have been living in for all their life? Why would we evacuate our home? Why are they lying to the civilians? They say that their air strikes target the militants, but this is all lies. They target the children, the house. It’s the sleeping people that get the air raids.”

Anja was a porn star, although she had tried working as a receptionist, a window cleaner at the Dundas mall, and even did a short stretch as a security guard for a high-end lamp company. Nothing seemed to stick. She said she did it out of laziness, she didn’t know how else to make that much money in so little time, though she never counted the money it cost to stop her from feeling anything at all before and during and after It was happening. All her “directors” — balding, sleazeball, former-leading-stunt-cock types who squatted behind the annoyingly lightweight digital pets which were thrust up into places their former erections might once have found consolation — complained that she was overdoing it in the moaning and squealing with pleasure department. Star was the putative term granted anyone in the industry willing to douche, body wax, anal bleach, pass the AIDS test and open her self-lubricated openings to an amphetamine-enhanced jackhammering before the requisite face splooging. As she grew further and further away from her body, her performances grew increasingly shrill and over-dramatized, so imagine her distress when she found, beneath Dani’s relentless babydoll ministrations, a return of the very pleasures she had worked so hard to be rid of.

Israeli Professor Neve Gordon: “The problem is that most Israelis say, ‘Israel left the Gaza Strip three years ago, and Hamas is still shooting rockets at us.’ They forget the details. The details is that Israel maintains sovereignty. The details is that the Palestinians live in a cage. The details is that they don’t get basic foodstuff, that they don’t get electricity, that they don’t get water, and so forth. And when you forget those kinds of details, and all you say is, ‘Here, we left them. Why are they still shooting at us?’ and that’s what the media here has been pumping them with, then you think this war is rational. If you look at what’s been going on in the Gaza Strip in the past three years and you see what Israel has been doing to the Palestinians, you would think that the Palestinian resistance is rational.”

One day Anja and Dani are out walking hand-in-glove because even the sight of shade makes Anja’s hands cold, especially the tips which nestle like ten freeze-dried buttons at the ends of either arm, so she wears Thermalite gloves even when the mercury is high like it is today. And while they are turning the corner which flanks the Supersave (which has grown a little less super in each year of its eight year operations) and the Mobil gas station (which has strung lines along its lot perimeter and hung them with American flags and begun to advertise Patriot Gas which causes the after-school smoking parties to snicker and pass between them jokes even the tellers are tired of) Dani and Anja are met with a hissing mumble of a chorus and then someone too young to know any better spits in their general direction, only the wind gusts up at that moment sending the gob right back to its originary moment like a baby crawling back into the womb. This rouses the confederacy of teenaged spitters who are all lined up on the aluminum postings which frame the stacked shopping carts, all of them laughing in a tight little round so that they don’t lose their balance and fall off, which makes them sound like they’ve never laughed in their whole lives and are just learning how. These laugh rehearsals only make the now spit-faced, pre-adult even angrier, a feeling which must be immediately shared with the two walking strangers who are named “Faggots” or “Rug Eaters” or “Pillow Munchers” or whatever he can think of from a gob encrusted brain grown suddenly seven times too small. As the boy-man’s D-minor taunts rise in the now breezeless air between them, they grow louder as each sitter chimes in with their own variations, but grow softer at the same time, at least from the perspective of the two women who move further from the corner lot on their way to nowhere in particular, a destination Dani refuses to feel is a mistake. Anja finds herself, unexpectedly, wanting the company of one of her large penis-men who would drown these no-necked teenagers in sperm and take her to a fine getaway resort island where all the residents are blind. Anja is still young enough to imagine that the blind are without judgment, perhaps because of her intermittent in-camera sessions which she can’t turn off when the director tells her she can go home. It is at this moment that, perhaps not coincidentally, a white truck jumps to life from somewhere behind the mosh of carts and chorus line grinners, and jumps right up onto the curb. But Dani sees the truck out of the side of her head, out of the place her gills might be if she were a fish, and she grabs Anja and pulls her out of the flight path and they throw themselves onto the grass median between the happy concrete of the parking lot and the unhappy concrete of what city councilors still refer to as the boardwalk, but which residents call the side of the road. The white truck runs across two lanes of oncoming traffic and hard lefts neatly in front of a Nissan whose driver is too surprised even to slow down, which proves unnecessary anyway, as the truck pulls ahead smoothly and vanishes around the bend.

The crazy thing is, that after Dani picks herself up from the ground the first thing she does is move her hands over her face like someone reading a Braille bible, because there is something going on there, something has changed and shifted and it’s still shifting. She can feel the asymmetrical planes joggle into some new formation as the beginnings of her new face settle in. Anja, who has dedicated her life exactly to not noticing things like this, has decided to get upset and blow up as soon as they both get indoors. She is determined to blame Dani for the truck, the misbegotten gob, the insults, and the very fact that there are teenagers still alive in this city. She fills herself with hate and grievances and disgust and fury, so when she picks herself up off the grass median she rushes over to Dani and strokes the place her new face is coming in and says, “Are you alright?” The mother of all concern. Dani stands there a moment, with the truck gone as if it had been a mirage and the teens scattered, and her great love seeming to love her more than ever now, and from an old spot on her new face she announces, quietly, sharing the secret between the two of them, “Yes, I’m fine now.”

American Robert Pastor (professor of international relations at American University): “On the part of Hamas, they made very clear that they had done what they could do to try to stop the rockets. And indeed, from the period from late June to November 4th, 2008, when the Israelis intervened in Gaza to close down a tunnel, they had virtually stopped the rockets. On November 4th, Israel intervened into Gaza to shut down a tunnel. There is some dispute as to whether that tunnel was intended to capture an Israeli soldier or whether it was a defensive tunnel to protect against an Israeli incursion. But in the course of that particular incursion, which of course was a violation of the ceasefire, six Hamas militants were killed. Hamas then responded with 124 rockets that month. But from their side, Israel had not complied with the ceasefire. It was supposed to have lifted all of the border crossings, allowing 750 trucks a day to go in. That never came close to occurring.”

There is something in the way Dani reaches for the tea… no wait. There is something in the way she holds the little cup with both hands, no, that it isn’t it either. Perhaps it is the way she tilts the cup up into her mouth while closing her eyes, as if she couldn’t look at anything at all and fill her mouth with taste at the same time. It’s at this moment that her face relapses into the very first mask she wore, as a newborn child. It’s a mask that might have announced, “I belong!” “I am like you!” It would have made her, yes, recognizable. Here was a face like all the others. Her mother would have taken her home to the father who hadn’t left yet in order to begin the traditional celebrations of catastrophe. There would be fittings for new roles, phone calls to family and friends, exhausted slugs of Prosecco frizante. Oh honey, I’m so glad you just underwent more pain than you’ve ever felt and chugged out our new babylove. Try not to laugh too hard or the stitches might stretch and burst. One day — not long after Dani’s father blew off on a spring breeze, taking part of her first mask of a face right along with him — she would make a choice, a terrible and terrifying choice, and decide to live as a monster, without any face at all.

This isn’t as hard as it seems because mostly no one notices. Like everyone else, I have spent most of my life busying myself with the task of not looking at everything around me, a sporting occupation that continues to provide undreamt comforts. The woman who used to be my best friend said that she didn’t have a body until she gave birth to her first and only child. It is difficult not to resent gifts as large and magnanimous as this. The pain was so relentless she was at last shocked into recognition. These bruised and tired hips, these fading shoulders. It’s me!

When I look into the mirror I can say yes to the body, the toes nearly webbed, the scarred knees, the legs I had learned only recently were no longer slender, but scrawny. But not the face. Who is that looking back at me with such curiosity? And dismay. Disappointment even. Everything I have tried to forget has somehow been layered up into that face, and the effort of this amnesia has marked and remarked it, so that the soft opening dish of childhood had very nearly vanished. And with it any hope of recognition.

I don’t try to speak to her from this face, instead, I listen. It used to be a face for speaking roles, now it listens. To each according to their abilities.

Dani opens her eyes and puts the double-handed cup back down with a care she didn’t manage when it really counted, back in Anja’s kitchen, so she’s extra careful now that it doesn’t matter. As the cup’s bottom lip settles with a soundless sound some force field of self-enclosure lifts and she is back with us in the shabby perfect restaurant, sitting next to the woman I can’t talk about who is smiling about something she’s already decided not to share. I stop holding my breath.

“The thing that Anja liked to do most,” Dani says and then stops, catching herself, and looks up at me. “Is this boring you?” My reaction shot tells her that if she doesn’t continue I will have to handcuff myself to her luggage and follow her back to the personal hell of her small town past in order to hear the rest of the story. Because I want her to go right on without interruption I don’t actually say anything, instead, I open my face up like a two-car garage door lifting when both masters arrive at the same time. It’s like one of those silent screams Bergman used when he couldn’t afford the fancy orchestral effects.

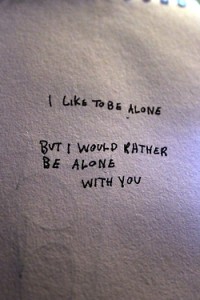

Dani takes the offered cue and plunges ahead. The thing that Anja liked to do most is to put on a record by Panda Bear who sounds just like Brian Wilson before the drugs and the California girls and the depression made him stop sounding like Brian Wilson. And while this almost-new Panda Bear record promises a dozen perfect summery songs she only plays the Brian Wilson cover tune, ‘In My Room,’ which is now swaddled in extra digital layers of vocal foam-rubber-like padding, the melody borne off in puff pillow clouds of happiness. Over and over.

“We didn’t break up the day the white truck nearly ran us over, but she got really mad and she stayed mad, and the more I tried to get her to stop from being mad at me, the madder she got. And she wouldn’t let me touch her in the kitchen anymore, only the bedroom, so I knew we were on, you know, shaky ground. And then I got busy with my own work because what do I look like, Mother Theresa of the lesbian porn world? No thank you. And every time I saw her she would be playing this song, over and over, until it was hard to want her anymore. I think she was turning herself into someone I wouldn’t miss when she was gone. Whenever she was playing that song it was like she was alone, all alone, listening to it. And the song, do you know it? The song is about “There’s a world where I can go and tell my secrets to in my room…” Not exactly fun fun fun. Not exactly Wouldn’t It Be Nice? It sounds stupid to say that we broke up because of a song but she was the one carrying the tune.”

We are eating hot potfuls of meatless bebimbap which I don’t taste until the very end because Simone, who I’m not allowed to talk about, and who is sitting in the frayed window light just beside Dani, says that the best part is the last bite because the flavours of dinners past and present have melted into the container and then juiced right back into the tightly clinging rice shards which have to be scraped away from their round iron setting. “Like dope resin,” I mutter brightly, and then resume my non-speaking role. She’s right, I realize too late, this really is the best Seoul food on a city strip jammed full of it. Too bad I’ve only woken up for the last piquant suggestion.

Before the invisible lunch appears, briefly, for a moment, right at the end like a curtain call, Dani takes out her small video camera and perches it next to the television which is still offering us a run of disasters from weeks ago. The floods in New Orleans for instance. The Free Gaza boat leaving from Cairo (it would never arrive). And of course, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, sounding like they were lifted off today’s ticker. Dani likes to take her digital camera pet around, and part of her genius is that she can go right on laughing and hurting and feeling the bruise and bring others alongside while the machine tries to absorb every moment in the room. Her pet has been designed by circuit benders to defeat the present, but she is a living workaround. I have no idea how she manages and thankfully neither does she. I worry that her only too evident super powers will vanish if we step on any sidewalk cracks or mention anything about it at all, so we don’t, especially not when we have so much delicious food to ignore.

Palestinian journalist Sameh Habeeb: “Today, in the early morning, there was a massacre in which around 20 to 25 people were killed from the same family in Al-Zeitoun area. Most of them were children. Israeli Army gathered around ten families in one of the houses for Al-Samouni family in Al-Zeitoun area south of Gaza City. They had gathered them in one house. And after a time, an artillery shell hit the house, and 20 to 25 were killed, and more than 60 were injured, because the house was including around 100 individuals.

This is not the only massacre today. We have more people being killed in the north, and more people are being killed in Gaza City itself. If you would like me to just state what we have today, I have a list of around 32 violations and ramifications of today’s actions. Israeli Air Force bombarded houses in Al-Shati refugee camp, and 35 people were wounded. And maybe more will be just dying, because the hospitals are not able to respond to the calamities we have, the catastrophes, because the Israeli siege, which was imposed around two years ago, completely paralyzed the ability of the clinics and hospitals to respond to any military operation or a war in such a scale like this.”

And then it’s time to go to Dani’s screening at Pleasure Dome’s address-less coach house at CineCycle, the laneway approach iced and pocked for maximum accident potential. As soon as she hits the door she is tucked into a welcoming committee of glad-handing strangers and queer romantic hopefuls, and her parents who have taken the power nap we all needed at the reassuringly American Howard Johnson’s a long way up the road in a neighbourhood which is becoming international in style — the concrete smudges and terraced caffeine dispensaries providing relievingly anonymous frames for encounters which could have happened anywhere but are here instead. The man who is not Dani’s father looks on with the same measured calm that he allowed to take the place of his face only a few hours ago. I watch from across the homemade bar as he lets the room drip into him one stifling encounter at a time. Dani’s mother, on the other hand, is beside herself, doubled and twinned and past nervous, and the words-only movie that Dani’s picked long before she knew her other half would be here — about the leader of North Korea urging men in his country to eat more pussy, comrades — is already causing her weakened chest cavity to ache in a nearly audible manner. The air escapes her without providing traditional oxygenating comforts. Ohhhhh. Mother’s slow release of breath signals a familiar surrender. Oh this again, her exhalation might be announcing, followed by a heady intake salve of this-will-be-over-soon, this-will-be-over-soon, chanted by how many in these same, avant-butt-worn, plastic chairs. It’s a good thing we’re not sitting shiv’ah.

American Mordechai Housman, on his website Being Jewish: “Many people worry, before going to comfort a mourner, ‘What should I say?’ The answer is: very little. A person in pain needs to talk, and he needs someone to listen to him talk. He doesn’t need you to say very much. Your job, in comforting the mourner, is to listen to the mourner, responding when necessary and appropriate. Always let the mourner take the lead in the conversation.”

Palestinian journalist Fares Akram (Gaza correspondent for The Independent of London): “My father was killed on Saturday when he was in our farmland in the northwest of Gaza Strip, very close to the border with Israel. We were very shocked with his death, especially that we have never expected he would be killed by Israelis, because he’s very close to the border, and that area is under control of Israeli cameras and the watching towers, and there are only a few houses scattered there amid the very large open spaces up for eight kilometers to the south until we get to Gaza. All that land, that area, are open, and there are no militant activities. We often thought that my father would be hurt from the rockets that are fired from Gaza, because, as I said, the farm is very close to the Israeli border. But we have never expected that he would be killed by the Israelis, who were watching him from nearby.”

And then at last one of Dani’s precious, throwaway, short missives made in a recent turn from Zionist heavy to Occupation witness hits the screen. She calls it 3 Parts for Today (12.5 minutes 2007). It opens with a bird lying on the ground in a cascade of grey and white feathers, heaving with breath, the yellow bill opening wide and all I can think is: how awful and beautiful. It must have hit that harsh brick wall and fallen here, in the last fine light where Dani (does she ever sleep?) has found her. Later on in the tape she shows herself (again and again, especially when she is not onscreen she is busy baring the wound) eating some kind of post food-nik, hippie cereal and she is talking to Yonatan about finding the bird, the nearly dead bird lying on the ground, and he asks her, “Did you help it to eat, to fly?” And she says, well, no, it was so perfect lying there and all, it was enough to bring the video camera close and watch.

It’s your catastrophe. It’s my movie.

Yonatan Shapira (named in the opening title as “The Refusenik”) talks about joining the Israeli army after the first Gulf War and becoming a helicopter pilot. He provides the frame for the central moment in this video diary (oh how she hates that word, it feels so very small in her mouth, particularly at the esteemed house of higher learning where she spends her summers trying to dodge the ism queens and other fences of the heart). She pushes her small eye prosthetic up into Yonatan’s face as if she would like to crawl into those poreless pores and make a home there. In the second scene she shoots him off a television screen that offers a talk he gives in a small, crowded room. Now that he isn’t busy flying rescue missions, and killing, and trying to keep his young testicles from being ground into shrapnel target juice, he has plenty of time to talk. Yonatan Shapira is speaking Hebrew, though the clip is silent (and shot home-movie style, in what looks like someone’s living room). Yellow subtitles permit language to be applied.

“And then a little seven year old girl started running towards us. On one hand I saw this little scared girl but then I thought about my soldiers behind me, maybe she’s a terrorist. Maybe she’s going to explode. I shouted but she didn’t stop…”

Incredibly, at this moment, a young girl gets up and walks by Yonatan. He can only smile and shake his head. “Yeah that girl was just about that high… but then I shot a warning shot in the air, the girl froze like this, for me it was like being hit by hammer on the head. For months afterwards I couldn’t forget that moment, and then I told my commanders I’m not doing this anymore.”

The scene that falls between these scenes, the meat of the sandwich, the picture in the frame, belongs to Grandma Leventhal. Dani’s own and only. You can tell they spend a lot of time together because their living room duet is lensed centimeters away from grandma’s left elbow, the camera pointed straight up into a wattle of neck and the sagging flesh of her arms. The scene opens — which is to say, the cut admits us to the instant — when grandma throws her head back as if she’s been shot, trying to strongmouth her daily pill into a gravitational purl.

“I can’t stand it.”

“And then you have to have a cracker?” asks Dani.

“Takes the taste out of my mouth,” says grandma through a face cramp, the flesh on her cracker arm joggling in cheerleader agreement. “What?”

“No, I just think that I don’t know why the pill doesn’t go down without you tasting it.” She doesn’t miss a thing, this kid, she doesn’t need her seeing eye dog to sharpen it up either, she’s on like a switch all day.

“Leaves a bad taste in my throat… I’ll get the prayer book out.” And then the old woman nods, right on cue, and it’s time for the refusenik to tell us about the little girl who wasn’t a bombshell after all.

It is an unnoticed moment, flashing on by at the speed of thoughtless thought, repeated how many times a day. But Dani keeps coming back to the small apartment and puts her camera down like it was still that little girl looking up into the sky of her relatives, the blood of her blood, the women that had made her mother, and then herself, Jewish. And she waits. Maybe she waits there all day, I don’t know, but we see only this shorn fragment, this remainder of what is not exactly host and sacrament, of what is hardly dinner, but it is eating all the same. Grandma is really eating it. But she is not tasting it. And it requires no advanced training manuals to understand that this scene is about the occupation of Palestine. It is about the Israeli West-Bank barrier which is being built mostly inside Palestine’s West Bank. Inside Palestine. It is about the illegal settlements in the West Bank and the Golan Heights. It is about checkpoint harassment and the persistent incarceration of Palestinian youth. It is about the massacres at Dair Yasin, Naser Al-Din, Tantura, Beit Daras, the Dahmash Mosque, Dawayma, Houla, Sharafat, Salha.

The pill is every “security” (state codeword for war against civilians, systemic torture) measure that Israel has taken in order to keep the body of state whole. The regular armed incursions into foreign territories, all this is justified and made necessary by the nearby presence of the malignant, the now “foreign agents” who have had their homes and homeland seized. The pill is also the pharmakon: at once poison and cure.

And the cracker?

I am the cracker. How does the Miranda July line go? Me and you and everyone we know. The corporate media plays its part and we nod along like a well-heeled chorus line, essential if those much-needed killing machines keep flowing from North America to Israel. Here in Canada, we build and export Caterpillar bulldozers which are used to destroy Palestinian homes in the West Bank. It’s your catastrophe. It’s my job.

This cracker talk spins away the pain, keeps the bodies well covered, and dishes the Palestinians as something less than human. The media is well rehearsed for this task. For years I watched, each and every night, cover stories about the war they called in Vietnam “The American War.” It is difficult for me to recall a single instance of a Vietnamese citizen speaking. Instead the Vietnamese could be seen lying dead, or else cowering in fear, or crying, or being trained by “us” to kill. And when “we” left that country it would not appear on the news every night, it was no longer of any importance what they did, or how they did it, or what they ever might have wanted.

“My grandmother was a very tough woman. She buried three husbands and two of them were just napping.”

So imagine my surprise when this grandmotherly scene lights up the confines of Toronto fringe movie exhibition palace CineCycle, the post-art house hipster revue where someone has found Dani, and plucked her small queer understandings from faraway Rosendale, New York, and brought them here, into the off-off-off-Broadway world of moving pictures. There is talk of an avant-queer genre, no less, already mothers and fathers have been named, bloodlines drawn and lineages established, canons hired if not fired, and now Dani has been invited onto these slippery slopes.

One would imagine it would be safe to say, “My grandmother was a Jewish juggler: she used to worry about six things at once,” or simply, “Peace.” I don’t even need to add that the curator is Jewish, and Dani’s screenmate likewise, and that the latest debacle, a 23 day killing spree in Gaza, ended on January 18, 2009, less than a week before tonight’s screening. The hospitals are still full, relatives are still burying some of the 350 children who died, the power is out, there are chronic food shortages. Why is no one talking about the dying elephant in the room? Instead, some of the gathered sages bring acclaim to co-presenter Aleesa for “moving on” from her early work and its overt questions of Canada’s immigration policies. She is commended for showing, in her most recent tapes, more universal truths. Yes, even here on the fringe, eternity has its place. Its secret hope. How much more tasteful and relieving is this embrace of forever themes like Time and Being, rather than having to dwell on what a little girl’s face looks like once she’s been dug out of the rubble of what used to be her living room.

Palestinian journalist Fares Akram (Gaza correspondent for The Independent of London): “Today, I have evacuated — I had to evacuate my wife to her family’s house, because it’s closer to the clinic where she’s supposed to deliver birth. It’s closer to the clinic than our house. In order to — you know, I can’t describe my feeling when I have to leave my wife alone in this situation and send her to her family house. And she’s also worried about me, because the tanks are getting more close to our house. And we know what the Israelis will do if they get near our house. They will call on us on a megaphone to come out of the house. And after that, most probably they will hit the house. They have set fire now to ten houses in the north of Gaza Strip, where, when I look from the window, I see [inaudible] of black smoke rising from the houses. I can’t imagine what will happen to our house.”

When I first heard the stories of the German camps from my father, I stretched out every detail until they were large enough for me to step into. What else were stories for? I was the little boy who found a way to get his mother smuggled off the train. The German guard who said no. The engineer who stopped the gas from working that day, if only for an hour, if only for a single session. I was always the one who said no.

My grandfather was a school principal in the Dutch-East Indies, and according to his contract, he was permitted, one year out of every seven, to travel free of charge back to the home country, with or without family, while continuing to receive his usual salary. He set out in the spring of 1939, only to find, a few months after his arrival, this strange, faraway country, which he hardly remembered from his youth, invaded by Germans. The German-Dutch war lasted five days (the Germans had expected to take Holland in a day, Rotterdam was obliterated by bombers by accident in the midst of negotiations), beginning on May 10, 1940. 9,000 civilians were killed that week. The colonial government in the Dutch-East Indies reacted to the invasion by declaring war on Germany, and rounded up all the Germans it could find on the islands and threw them into jail. The new German government responded by putting all the Dutch-East Indians into concentration camps. Including my grandfather. It is a scene which my father has often described to me, always at the beck of my persistent urgings, but seems hardly credible even when repetitions produce negligible variations. The well-fed goose stepping machines with their backasswards motorcycle-style helmets and their fetish pistols show up to the door one day, the door of my family, and demand to see my father’s father, and then carry him away. ”Don’t worry little boy,” the sergeant says to the little boy waiting at the door, “Your father will be alright.” My father recounts this episode with a frisson of pride because even at this young age he was able to speak German, along with Dutch, Indonesian, English and French. Though he was interested only in the dreamy escape hatch of mathematics. When he speaks of this impossible scene, the Nazis arriving at gunpoint to haul his father away, he dishes it in the same benign about-to-laugh tone that he uses for all of his stories. “Two drunk guys walk into a war… you’d think they’d see it coming.”

When my father talks I am the one wrestling the German soldiers to the ground, breaking their will with borrowed kitchenware, freeing my grandfather, taking my family away from the occupation, from Holland, and then from every dreaded place of war. Don’t get me wrong, I never think badly of my father for not doing more, he survived the five interminable years of occupation with almost nothing in his stomach, and then watched his own father come home, broken and sick and unable to speak of the nightmare of those five years. The emotions he could have had, the full orchestral colouration, must have shrunk to a single instrument in those years, and he’s been condemned to that tune every since. After the war my grandfather recovered just enough to become an alcoholic which prompted his wife to have him declared mentally unfit. Once again he was hauled away, this time by medical authorities. He rang curses down on my grandmother as my father looked on, patiently turning the whole scene into vector diagrams and electrical diagnostics. My grandfather spent the rest of his short life in a state hospital, cutting out food adverts from the local papers. Drinking coffee he kept hoping would turn into beer or some other golden formula that would stop the feelings from coming again.