- Philip Barker (pdf)

Philip Barker and the Modest Spectacle of Trust

The longest illegal screening in Canadian history is playing even as we speak, between the gentrified columns of Citytv’s new Toronto location on Queen Street. 15 slightly larger-than-life monitors broadcast the station’s daily outpouring of local trivia, music vid posturings and made-for-TV consolations. Playing without the sanction of a redubbed Ontario Film and Video Review Board (formerly the Ontario Censor Board) this shift from the domestic commonplace to outdoor spectacle had, for three chilling nights in October, a companion piece. Entitled Trust A Boat by Philip Barker (film) and Marianna Ebbers (performance), this media mix was installed just beyond the confines of Citytv, in a parking lot cleared especially for its audience and a warehouse just behind.

Ros: We’re on a boat. (Pause) Dark, isn’t it?

Guil: Not for night.

Ros: No, not for night.

Guil: Dark for day.

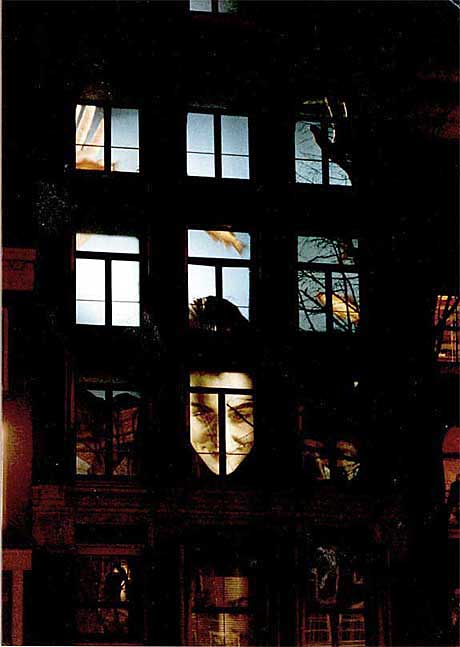

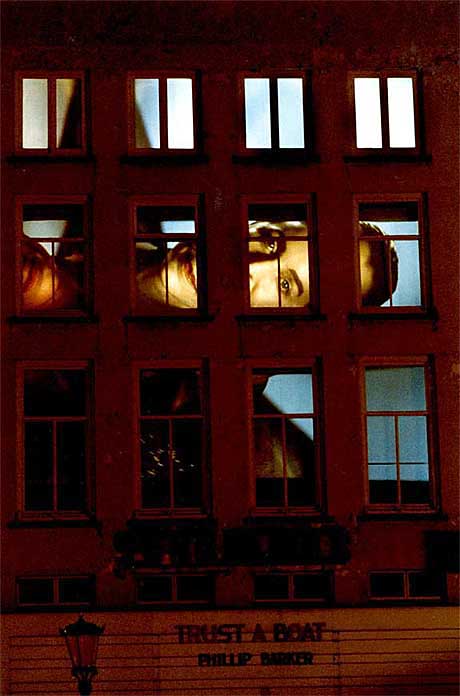

Laid out on a nine-screen grid, each of the warehouse’s window screens is paired with a projector, nine in all, which are synchronized together to produce the fractured pictures of Trust. Originally shot in 35mm with the camera on its side, to match the vertical orientation of the window/projection screen, the original footage was then refilmed in a series of nine staggered close-ups, which together would produce a single, unified image.

“Trust a Boat started as an idea I had from watching windows when I was living in Amsterdam on the fifth floor. Across the street were a series of apartments where people all seemed to do things at the same time, like at 11 o’clock they’d watch the news. They would all be watching one of the two Dutch TV channels so the rooms were all lit up with one colour or the other. It created very graphic patterns running through the building… (Philip Barker)

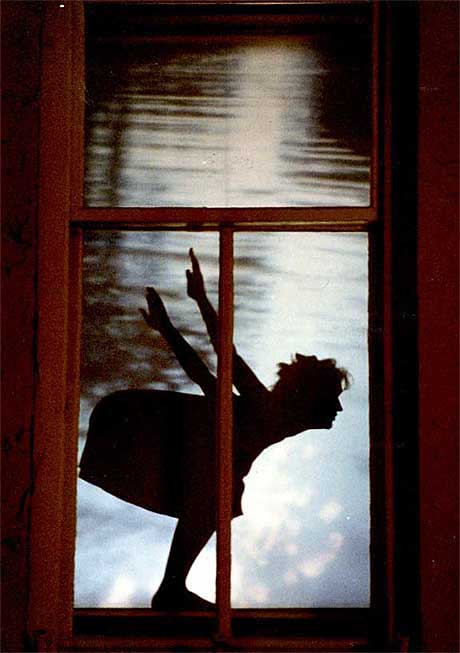

Eschewing the Cubist strategies of fragmentation and spatial montage, Trust’s images are remarkably coherent. While the film opens with a silhouette standing in the middle frame (wearing a boater!) the screen soon discloses the image of an aquarium with Hanna Schygulla-lookalike Patries Moulen peering into its watery interior. Presented with an image of our own looking shot through the metaphor of public life as fishbowl, the scene dissolves to an Amsterdam street where an accordionist accompanies the traffic of merchants and their charges. While there is no boat in Trust, when the sidewalk floats from beneath the feet of the accordionist, he tests the emptied space with his boot (‘boat’ derives from the Dutch ‘boot’). In a startling moment of composition, Barker applies the camera directly to the accordion’s splintered surface, filling the nine projection screens with an image whose undulating rhythms of expansion and contraction seem to birth the face of Patries Moulen, set this time in a slowly turning revolution that gives way to an incoming sea (Moulen’s outlook is answered by the sea waves). A brief section of pure colour passages follow, the windows winking in chromatic turns before a host of real-life silhouettes take shape before the rear screens.

“The choreographer, Marianna Ebbers, had made an audio guide track that was playing in all the rooms. We had decided that at certain points the people in the house would suddenly do the same thing and then fall out of sync again the way the film did.” (Philip Barker)

Nine performers, one in each window, enact daily rituals of house keeping and employment: cleaning, cooking and drawing out papers. This series of gestures become, through their simultaneous presentation, a meditation on the way disjunctive and fragmentary moments in our lives are imagined to exhibit coherence through the application of a narrative that will sum up or account for the past. As the lights slowly fade a single performer handstands his way toward the window before executing a clown-like fall and the show is over.

Guil: Yes, I’m very fond of boats myself. I like the way they’re contained. You don’t have to worry about which way to go, or whether to go at all. The question doesn’t arise because you’re on a boat, aren’t you?

Trust seems remarkably free of the image/text conflations that have become such a dominant theme of so much post-structural work in video, film and photography. Saussure’s Course in General Linguistics (1916) which posited language as a series of differences whose meaning is dependent on its relative position within a system, alongside Lacan’s seminars, entered film criticism through the writings of the Screen magazine group in the seventies. A global copulation of image and text ensued, as if the bond between an image and its referent or an image and its viewer was impossible without the mediation of the word. If all art once aspired to the condition of photography (Walter Pater), today it aspires to the condition of criticism.

But Barker’s allusive montage does not entirely displace the hegemony of the word. His Trust, after all, grew from a commission (synonym of trust) housed in a property committed in trust for the benefit of another and presented free of charge to its audience (trust: to see goods on credit). But the largest trust is inevitably brought by an audience to film’s draconian methods of presentation. In no other medium is one so apt to find the gestures of recrimination and outrage that has often accompanied the screenings of film art. While modernist exhibitions of the past have provided traditional sites of transgression, the ideologies of progression and rupture have largely given way to a postmodernist “levelling of history.” In spite of all this, Toronto grandly named film bout “The Festival of Festivals” provides an annual forum for outrage as an unsuspecting public castigates one more film that is understood in terms of its deficiencies. It doesn’t have a plot. It doesn’t have characters. It doesn’t progress in a linear fashion. Because the establishing shot of public cinema is often the same as the avant-garde – with its darkened theatres, film screens, projectors poised at the back of the room – the expectations attached to film’s infinite rectangle assume a continuity of expression. “I have sat in this seat before, or another like it, in a theatre quite like one, and when the film starts I’ll know what it is, because it should appear to me as familiar as my surroundings.”

In the collective anonymity of the theatre there is a kind of trust passed between spectator and image, a trust in the theology of form, that there is only one way to put one image next to another, all points moving like the perspective lines of vision towards a final point of resolution, to the end of the story. We might say about the conditions of film’s presentation: that cinema is a victim of appearances, or that loosed from the moorings of traditional signification a new kind of trust suggests itself.

Guil: (leaping up) What a shambles! We’re just not getting anywhere.

Ros: (Mournfully) Not even England. I don’t even believe in it anyway.

Guil: What?

Ros: England.

Guil: Just a conspiracy of cartographers you mean?

Ros: I mean I don’t believe it! (calmer) I have no image. I try to picture us arriving, a little harbor perhaps… roads… inhabitants to point the way… horses on the road… riding for a day or a fortnight and then a palace and the English king… That would be the logical kind of thing… But my mind remains a blank. No. We’re slipping off the map.

Barker’s sure-handed use of the film medium is married to a radical incompleteness that everywhere suggests connections without making them explicit, without terminating its diffusion of possibilities. Just as he has “come halfway” towards his public by bringing his film/performance work out into the street, Trust breaks with the monologue usually associated with the proscenium and extends its narrative powers to an audience that will learn to trust themselves or forever give themselves over to the master/slave relations “new Canadian” cinema hopes to borrow from its American fathers.

Ros: We drift, downtime, clutching at straws. What good’s a brick to a drowning man?

Guil: Don’t give up, we can’t be long now.

Ros: We might as well be dead. Do you think death could possibly be a boat?

Guil: No, no, no… Death is… not. Death isn’t. Death is the ultimate negative. Not-being. You can’t no-be on boats.

Ros: I’ve frequently not been on boats.

(All quotations are taken from Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead by Tom Stoppard. London: Faber and Faber, 1967)

Originally published in Composition Magazine, Fall 1989.