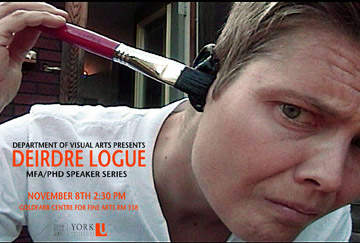

Deirdre Logue: Transformer Toy (an interview) (2001)

Deirdre Logue’s films return to the first-person stage of early video art. They are monodramas rehearsed for the camera, and the artist performs in each film. They are wordless, demonstrating the cost of living in a body, her skin appearing as a book, written over and over, and without end. Perhaps the collection of our habits is what we call personality. For years Logue laboured to celebrate the work of others, beginning a fringe film/video festival in Windsor and rejuvenating Toronto’s Images Fest. She has sat on endless boards and committees, part of that vast corps of volunteers that keeps the wheels of the fringe turning. Over the past three years she has been at work on a cycle of her own, a ten-part movie whose flickering, hand-processed surface examines the darkest of human leanings with compassion and humour. It is photographed, of course, in close-up.

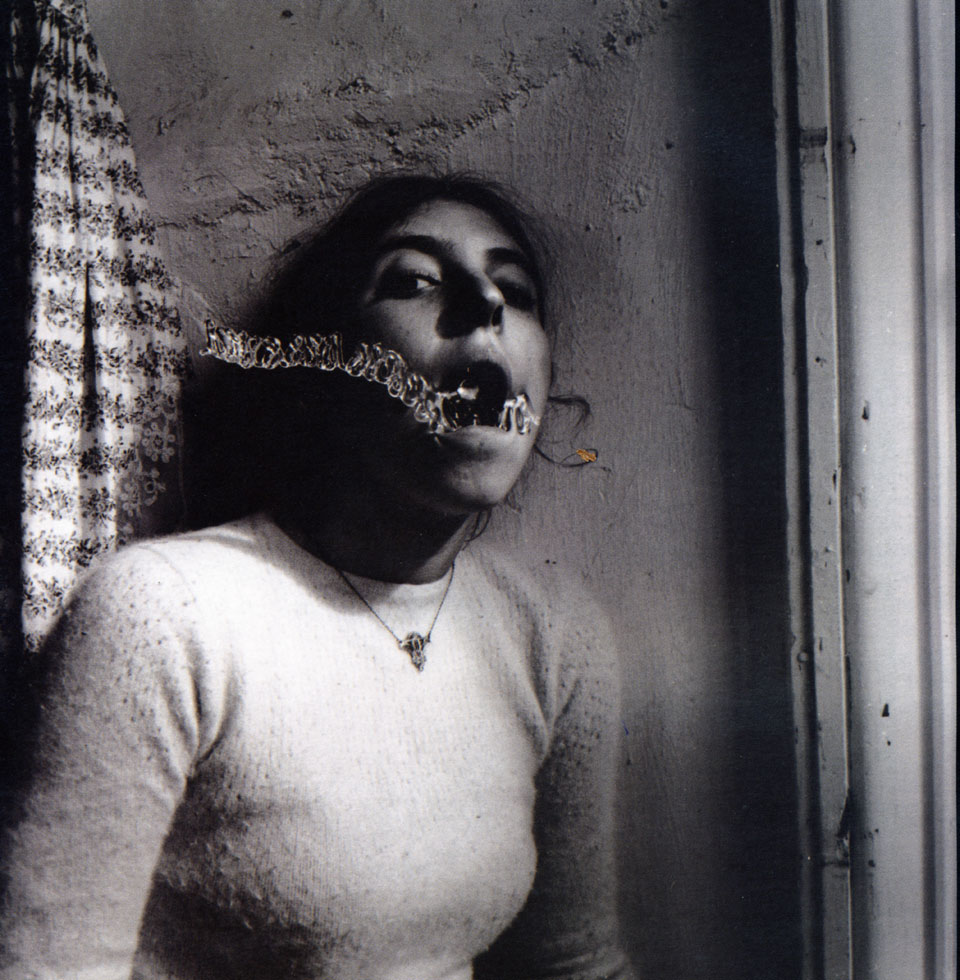

DL: A woman with a mouth like a catfish is showing me her whiskers. They work like snake tongues, emerging and retracting from tiny holes at the side of her mouth. When visible, they move as if sensing or smelling. They are incredibly articulate and delicate. They also seem to present a danger, as if able to transmit a poison. I can tell right away that she is not who she appears to be. These whiskers are part of her but also a deliberate disguise. I am hypnotized by the movement of her tiny tongues, unable to move. I am both terrified and amazed. As the body is broken down into its transmittable lines per inch, it can then be reconstructed into other forms of transmission. This breaking apart takes no prisoners.

I have always been in love with performance art. Even as a child I was fascinated with the potential for both eliciting and sustaining a performative tone. Changing my name for strangers was just the beginning of what would fast become a lust for an increasingly fluid sense of self. Scolded on a regular basis for lying about who I was, I began to realize that this desire was never purely intuitive but rather a strategy for surviving a serious case of ambiguity. As well as being myself, I was also names, genders, and identities I made up: Michael, DJ, Corey, Maggie, Paul, Sara, Kevin, and Gary. I was all six of the Brady Bunch siblings (though I never identified with the kid added in later episodes), five out of Eight is Enough, Jodi from Family Affair (unlike the actual character, however, I knew kung fu), Sabrina from Bewitched, and the star of Gilligan’s dysfunctional coconut isle. I refused to answer to my given name enough that I forced my mother and father to call for their daughter Kevin in the school parking lot. My patient parents eventually drew the line after one full week of watching their eldest child eat out of a dog bowl in the corner of the kitchen under the guise of Pal, our long-dead family pet.

Early shape-shifting prepared me well for adolescence and I survived, as many of us do, by developing new identities over and over again, depending on who was asking. Once past the threshold of my sixteenth birthday, I felt I was entering a new era of self — a directed adult self who knew what she/he wanted — though I never lost my fascination with performing several selves. I am who I need to be when I need to be somebody else. I am in a constant state of becoming, a sign of the future of who I may become. I am not singular. In my dream I am a Transformer toy, the blue one that is a motorcycle that turns into a Power Ranger character. I am in the middle of the transformation process when I hear my mother crying out for help. I must get to her or she will surely perish. In a panic I rush the assembly and put myself together in all the wrong ways. My head is in the right place but I am quickly becoming a jumbled mess of man and machine. As my mother’s cries intensify, parts are everywhere and I accidentally break off one of my arms. In its place grows a spoon. I can see my reflection, and as if seeing myself for the first time, I begin to weep.

I remember a girl in my first college art class who was obsessed with the image of the horse. We were given a 2D metamorphosis project to be executed in gouache. We were to take the simple self-portrait and expand its potential into the symbolic by moving from portrait to object in five stages of visual transformation. I spent a weekend at the kitchen table turning myself, rather unfortunately, into a cherry. I ended up looking like I was the Jackson Five. She, on the other hand, went from a timid, self-conscious soul into a complex, dark, and unpredictable brooding stallion. I was deeply jealous. We easily lose sight of the body yet it is always in view. She has been stolen and replaced with another of herself. We have a hard time keeping track of her position, her placement, her subjectivity and identity. She is all and none of what we need or expect her to be. She is in motion, shifting when and as she chooses. Her mediated image is constant yet her survival requires that she never stand still.

MH: Can you take me through a bit of your history?

DL: My partner, Kim, was accepted to the graduate program at the University of Windsor, so we moved from Vancouver. There was a job opening at Artcite, Windsor’s artist-run centre. After I had been working there for a year, Artcite decided to do some film/video programming. Hoping to encourage local production outside the university setting, I started the House of Toast with four or five others; the collective scraped together all the equipment we had between us. Our first official project was called Two-Minute Videos, where anyone could come and make a short tape over a weekend and be fully supported. The collective did all the technical stuff. We made ten over that weekend and had a screening. It was a way to introduce video, and some of the tapes were really great. Later we teamed up with the Detroit Filmmakers Coalition and started up the Media City festival which I ran for a couple of years — it’s still running. People became interested in seeing images of themselves, and we were their eyes, taking on a documentary function for a while. We documented The Heidelberg Project, Tyree Guyton’s neighbourhood art renovation project in Detroit, and were hired by local rock band Luxury Christ to document their Jello Sex Cult CD release. Windsor is a lonely place for artists, so they do more than go to board meetings together.

At the same time I took a course at the university and made two films which aren’t in distribution because I consider them student exercises. The first film was called Sniff, and it shows a woman crawling across a gravel parking lot sniffing something out, about three minutes long. Sound familiar? I was one of three women in the class, along with future directors of National Lampoon 5 and Die Hard 56. They were all wannabe monster-movie makers, awful young people who made films in their dorms, drinking beer and killing each other with fake guns. To supplement my income I was working in a homeless shelter for women and the job was killing me. I’d worked in transition houses and rape crisis centres before, but this particular shelter was very violent and poorly managed. One woman came with her husband from New Brunswick only to lose everything at the casino, and now she’s sharing a bed with a sixteen-year-old junkie from Detroit. It was like a prison, you couldn’t do any real work there. So when Kim finished university we moved to Toronto, and I got a job with the Images Festival, a ten-day event held every spring which runs mostly short film and video work by artists, as well as installations and performances.

MH: Tell me a story about Images.

DL: In 1997 we moved to the Factory Theatre in a bid to regain a sense of tribe. We had to clear out the barn and put on a show, but were unprepared for the level of rehabilitation the venue required. We did a lot of cleaning, built a booth, hung a screen, hauled in a portable 35mm projector, took out seats, the works. Under my stringent direction we were, of course, behind schedule. So it’s about three in the morning the day before opening, and we’re beyond exhausted, people are freaking out, and the projector won’t fit in the booth so we have to cut part of it open. Then we all settle back and watch Black Ice, and it looks so beautiful, the image large and clear, it’s the first thing onscreen after all that work. Then someone asks, “Do you smell smoke?” And our projectionist says, “Holy shit!” and we look back to see the projector’s on fire. We opened later the same day. I think that festivals are social events as much as sites for discourse, though a lot of fests hold onto the idea that it’s really about the work, as opposed to a context within which people can talk about cultural activity in general. Too often festivals create a mandate that becomes a code of behaviour. A festival’s mandate should change at least every year, as the cultural climate shifts. It wasn’t until I quit Images that I could make my own work.

MH: Could you describe Enlightened Nonsense (22 minutes,16mm and video, 2000)?

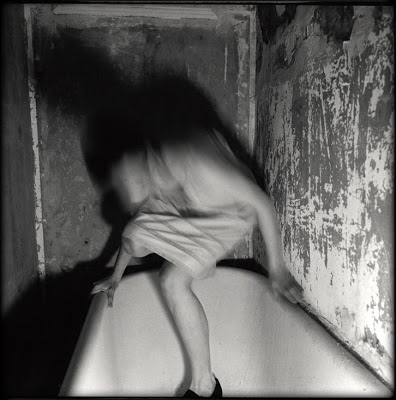

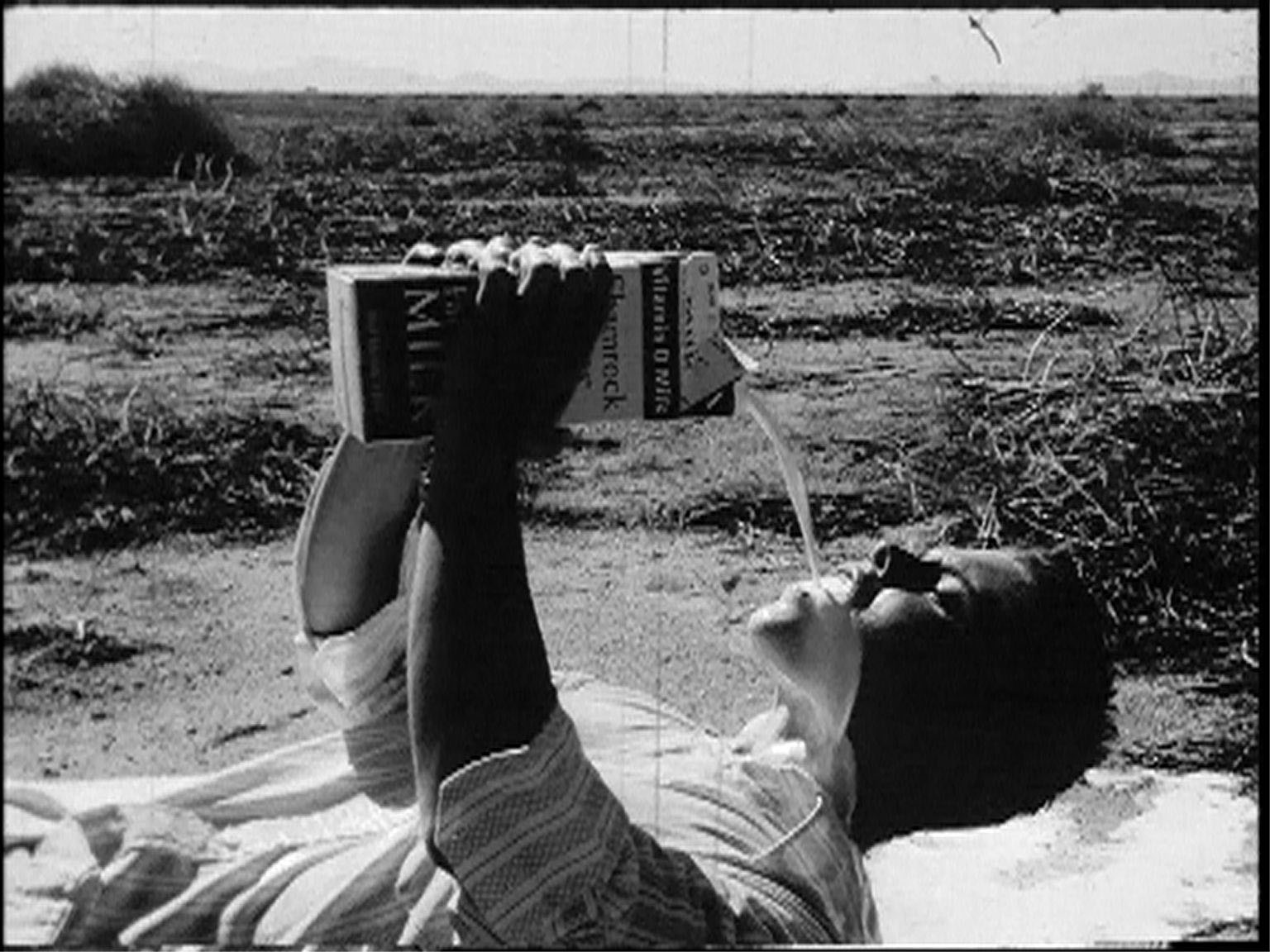

DL: It’s a series of ten thematically related films. They were made over a three-year period, from 1997 to 2000, and each of the films was shot, hand-processed, and edited in about a week. I am the primary performer, director, and technician. This method has made it possible for me to leave behind scripts and crews in favour of a more immediate, self-contained workplace. When I started this cycle of films I described them as fantasies of my own death. But these fantasies are very complex; they might include going shopping, for instance. On the other hand, after performing these actions, there’s something very real about ripping tape off your face for two days. You return to the present. I’ve had a lot of different responses to the work — many negative, but none without fascination. What was I expecting? The work is not made to disguise itself. What compels an individual to draw stitches all over her body, to wrap her head in tape, to gorge on milk and cream, to fall repeatedly, to soak her head in water, to be hit on the head by a basketball over and over, to put patches on her face or thorns in her pants, to lick up the road? The work urges its audience to ask questions. What would compel me to do this? What might compel them to do this? As an artist, when I perform these actions alone, the audience is already there, on the other side of the camera.

MH: So you’re not really alone when you’re making the work?

DL: Metaphorically true. There are three parties in the primal scene: the child and two parents. The child is the witness, the parents are having sex, devouring each other, or so it appears. I am one of the parents, paired with the audience. The camera is the witness, maybe, I don’t know. The camera is an object that views; even though I set up the shot and pull the trigger, part of it is still outside my control. It translates experience according to a machine dynamic. It creates a point of view that I respond to. In Roadtrip it’s supported by pebbles on the roadside, forcing the audience to lie on the ground and watch a horizontal experience. Every time I take my camera out of its case there’s someone behind it. Someone other than me. If you want attention or affection you behave in a certain way, you perform, and it’s the same when you’re in front of a camera. You perform in order to elicit certain responses. In the end, the audience looks through the camera, the seeing machine, in order to witness my behaviour. There was a group of women, all around fifty, who came through the YYZ gallery while my installation was running. They watched the piece and then I joined them for a discussion. One woman said, “I feel so sorry for you, and I feel sorry for your body.” Another said that any young person could walk in here and be completely traumatized, that I should put a sign up on the door. But I stuck it out. I asked the woman why she felt sorry for my body, separate from me. I spent an hour with that group, don’t ask me why. They went from Enlightened Nonsense to the restaurant for blue-cheese tarts and a glass of white wine, then off to see the Manets. It was important to talk to them, maybe, because words are familiar to them, while pictures are strange, unless they’re on TV.

MH: Can you tell me about Phil Hoffman’s workshop?

DL: It was the first opportunity I had to focus on my work in many years; the fact that it was also a beautiful place in the country where I could talk about what I wanted to do was icing on the cake. The workshop takes place on a farm with a screening facility, darkroom, editing suites, and cameras. It’s one of those places where working through the night is so easy that morning is a disappointment. It puts pressure on you to experience, not to produce. During five intense days, you get to watch others making, their mistakes and successes, and everyone puts their heads together to solve different conceptual and aesthetic problems. It helps remind you that you’re not the only person on the planet, that helping others and asking for help is one of our joys. Seven of the ten films were shot there.

When I made Fall I shot 500 feet of film of myself running away from the camera, throwing myself on the ground and then running back. All that stuff in between is some of the best stuff. In the films where I’m right in front of the camera and I have to lean forward to turn it on and off… so much gets made there. I try to work alone as much as I can. But sometimes when I’m using a Bolex, I don’t have time to run into the frame and perform before the camera wind is over. Sometimes I can’t see what’s really going to happen. But I prefer working alone — the relationship between the camera and performer is so important.

My films are autobiographical but refuse storytelling. Each has clear parameters, so it’s like you’re looking at my arm as opposed to all of me. They are the result of spending five days a week on an analyst’s couch trying to understand things about myself that are dark and complicated. I feel like I’m better at talking about it as an artist than I am as a human being. The unconscious is very tricky. The unconscious is like someone who pulls all your plugs out and puts them back in another order. But the actions I perform in my films are not extraordinary or bizarre. I use common objects and familiar scenarios. Basketballs, packing tape, water, whipped cream, dirt, and underwear — these are everyday items. Their strangeness and intensity derives from repetition. Humiliation and discomfort are pretty normal kinds of feelings. Masochism is how we get along with others. I’m just giving these feelings a different shape. While there is a recurrent masochism in the work, I have to object to labelling it self-abuse. This simply doesn’t say much about the content of the work. I don’t make films where I stick my head in a bucket of cold water over and over again to prove my machismo. I don’t make films to show people how much pain I can take.

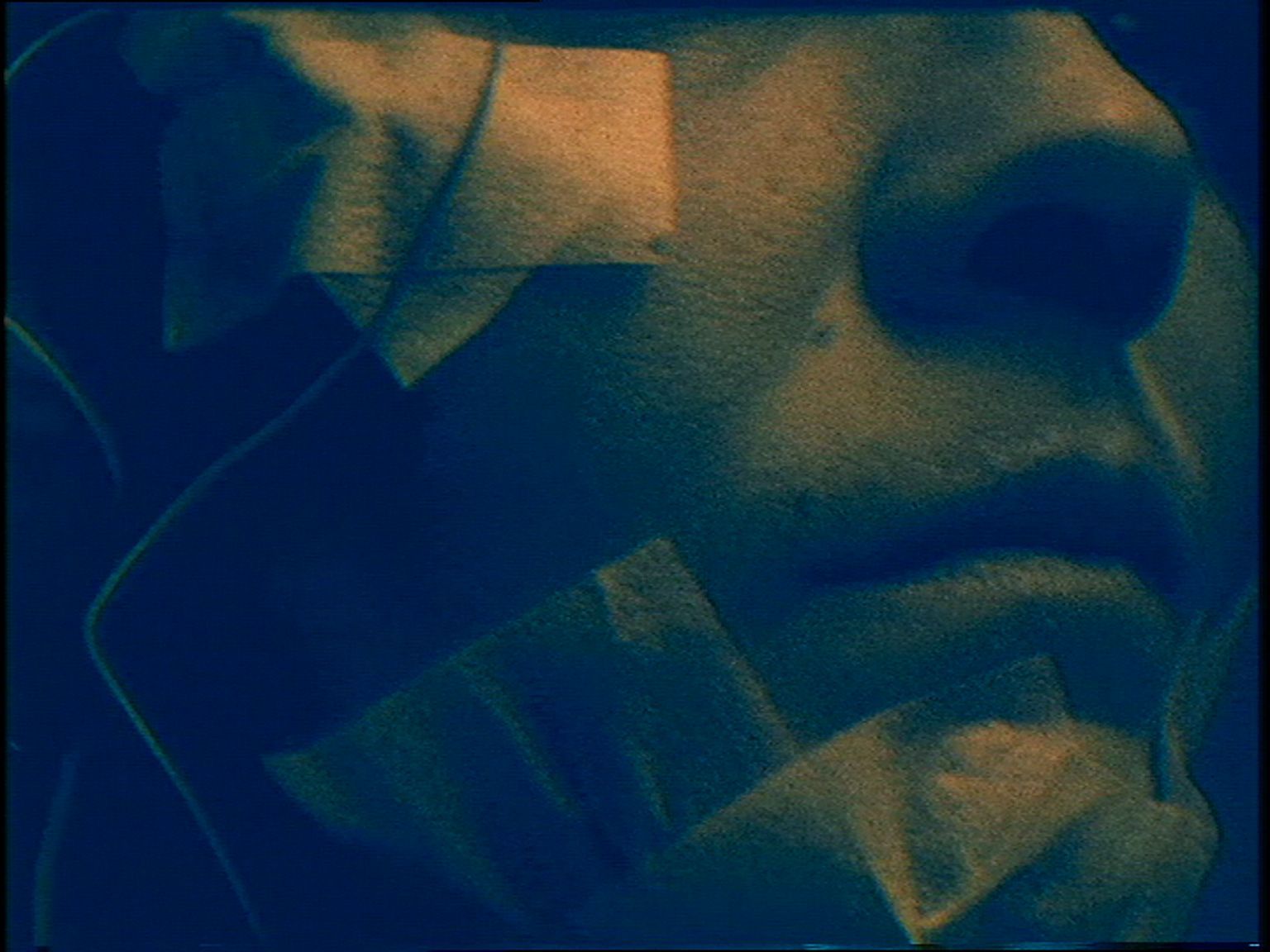

MH: You’ve foregrounded the surface of the film.

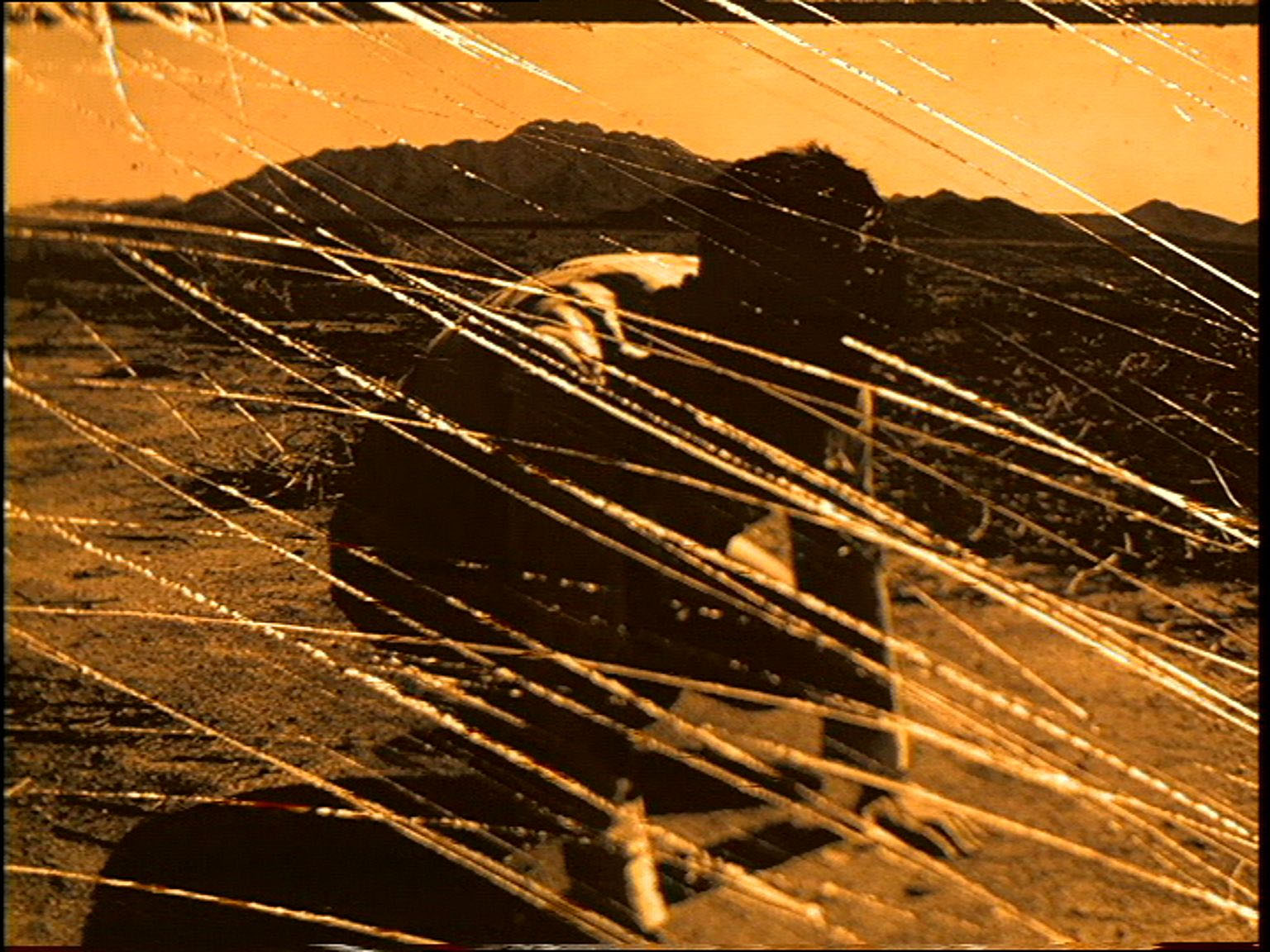

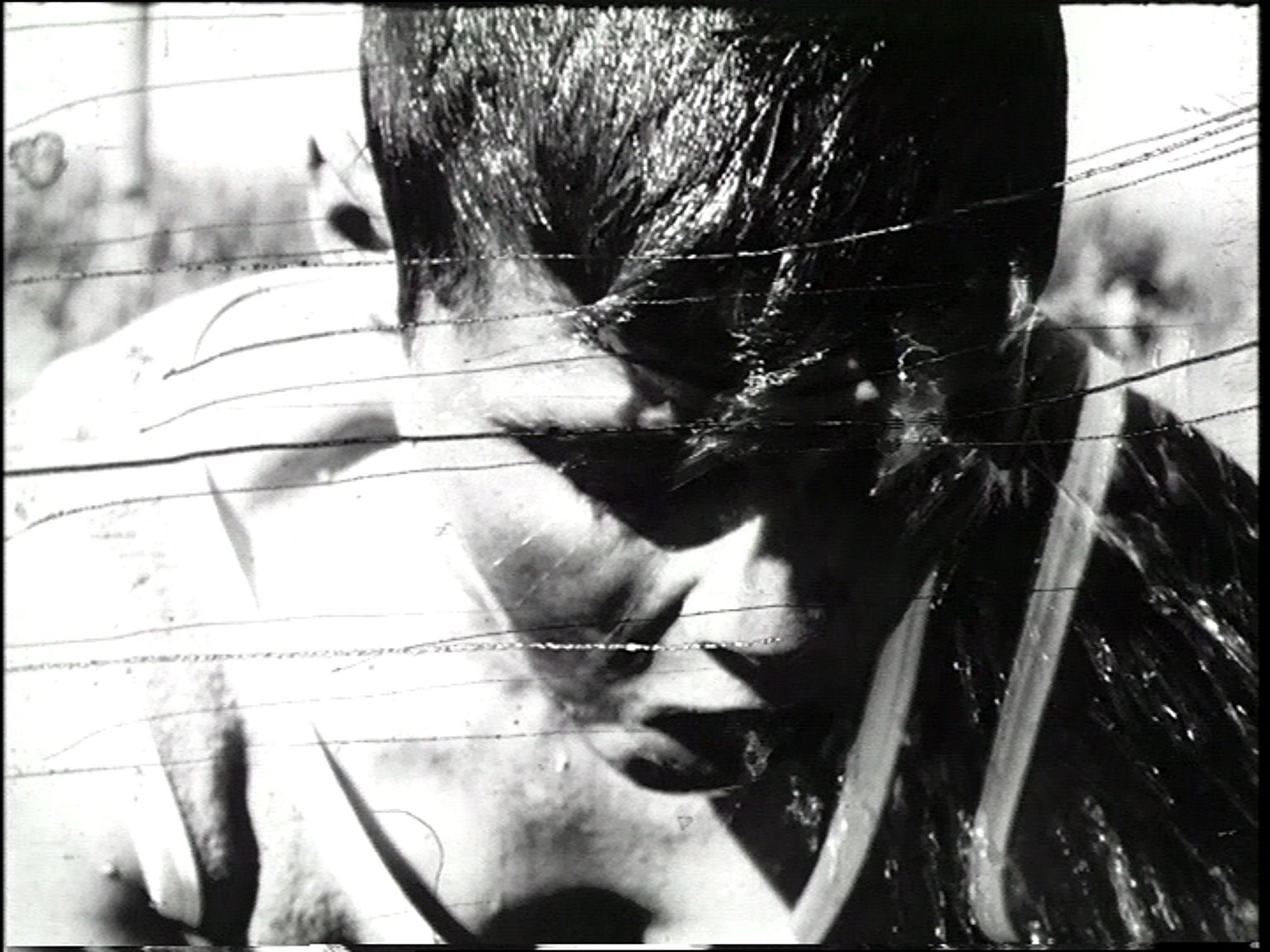

DL: The form and content are related. The film feels handmade — it’s been scratched on, sections have been tinted and toned, and it’s all been hand-processed. I cut the original, bringing all the abuse of the film strip into the editing room. The body of the film and my body arrive together; they’re both physical events. The sound is brought into the film two ways: first, via the found footage, which has its own soundtrack, but because the sound is scanned later than the picture on a projector, all of the sound appears about a second after you see the image; the second way sound is introduced is by drawing or marking on the area where the optical head will read it. Any variation in emulsion will produce sound, so when I’m tinting, toning, and processing, this is also adding a sound element. These sounds are sampled and looped on the Avid (digital video editing machine), slowed down, and fucked with.

MH: Tell me about Sleep Study.

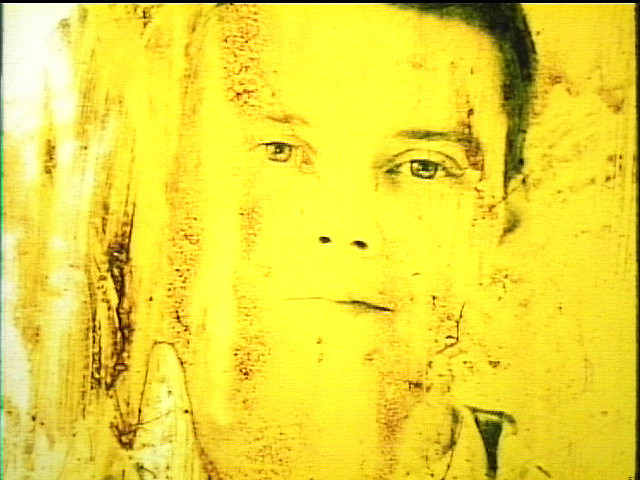

DL: In Sleep Study I included footage of myself as a kid, precociously dancing out in front of my elementary school, and then it cuts to footage of me during a sleep analysis (I suffer from various sleep disorders, and I photographed myself at the clinic, attached to wires and probes that monitor my sleeping). When it returns to the home movie footage, I’ve fallen down and hurt my knee. I’m crying and walking home to my house, which is in the background, and the neighbourhood kids run into the frame trying to help but I don’t want their help. I get to the front door and it’s locked; no one’s home because my parents are busy shooting a movie of me trying to get into the house.

MH: Is it more difficult for women to make work than men?

DL: No. Both genders are capable of experiencing equal pain, confusion, and anxiety, so if you make personal work it’s equally difficult. I grew up in the artist-run-centre movement, which was always a fantastic idea, but they needed women to come in and run them. Art needs chicks. Festivals, publications, galleries: they’re all being run by women. Why? Because women are good at diplomacy, collective communal behaviour; girls like to share, they’re capable of interpersonal intimacy in the workplace, are tidy and good with money, and have excellent penmanship. The primary cultural worker bees have been women, once you step outside the fact that all the institutions are run by men. But I’ve never lacked entitlement or luck.

MH: Why are you making a series of films?

DL: Too much spare time. I like multiples, twelve ears of corn, ten related films. I like the idea of having one problem and ten solutions. Some of the pieces are very brief, just thirty seconds long, and they reveal themselves best when they’re rubbing up against other things. This is considered pretty normal in the art world. Painters and drawers rarely show work one at a time. Singers don’t sing one song, they release albums. This is my album. What else do you want to know? I took lessons in dance and karate, played softball, went to Girl Guides, brought home stray animals, ate already chewed gum off the concrete, and was a chronic nose picker. My mother claimed I had a fecal obsession as a child which, thank god, hasn’t panned out as anything serious. I was a TV junkie as a child and still am. My favourites are the commercials. The first movie I saw in a cinema was Oliver Twist, and I cried the whole way through. When I was a kid I had three favourite things: a drum set (yes, I was a child prodigy on the drums), my collection of monster-movie models (Wolfman, Phantom of the Opera, Hunchback, Mummy), and a book of short stories that I still have, most of them extremely violent and uncompromisingly ruthless to children.

MH: Is there an avant-garde today?

DL: Only in fashion.

Deirdre Logue Filmography

Enlightened Nonsense 22 minutes (16mm and video) 2000

This cycle includes ten short films

Patch 1 minute 2000

H2Oh Oh 2 minutes 2000

Moohead 1 minute 1999

Road Trip 1 minute 2000

Always a Bridesmaid… Never a Bride of Frankenstein 2 minutes 2000

Scratch 3 minutes 1998

Tape 5 minutes 2000

Sleep Study 2 minutes 2000

Milk and Cream 2 minutes 2000

Fall 2 minutes 1997

Originally published in: Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada, ed. Mike Hoolboom, 2nd edition; Coach House Press, 2001.

Deirdre Logue’s Enlightened Nonsense (2001)

Nothing ever happens for the first time. History, my history, is an echo. Like the words that come out of my mouth. I have never used a word for the first time, though I want to, desperately. I want to get out of the trap of repeating, of using someone else’s words (whose?) to describe my own experience. I want to invent, to make art with my mouth. But whenever I try, I stop making any sense at all.

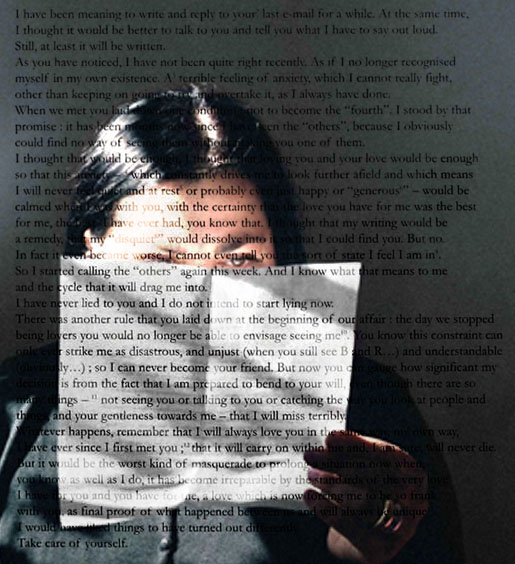

Deirdre Logue’s Enlightened Nonsense is a series of ten 16mm films, mastered on Betacam SP, and transferred to DVD so it can loop in gallery settings. Everywhere I see her hands. Touching, scratching, toning, erasing. These pictures have come out of her hands. Out of her body and the body of film. She has kneaded this emulsion, allowed it to bear its secrets, to impress upon its transport of emulsion and acetate, the beginnings of witness. This is an action movie with one protagonist. A monologue of the body. Not a confession, but a testimonial. It is a portrait of everyone who looks, a study of compulsion and repetition, in other words, the way we make meaning. Our selves. It is photographed of course in close-up.

Each action is as simple as falling down. Starting over. Getting hit by a ball. Drinking milk. Removing tape from your face. Wishing it could change but it can’t. Putting magic marker stitches on your arms and face. No action appears just once, but over and again. This is the way the body remembers and forgets. Or better: this is the way the body performs the join of the past and present. In order to remember, it must forget. These are letters from the department of redundancy department.

I have always loved titles. Imagine my delight, my delirium even, in discovering ‘foreign’ films which typically featured hundreds of titles. Walter Ong: “If a picture is worth a thousand words, then why does it have to be a saying?” Perhaps it’s because I don’t have children, denied the task of naming. Deirdre Logue has produced titles for each of her labours, which appear like headings on a specimen jar. Here is a list, beginning with my favourite, in a descending index of pleasure.

1. Always a Bridesmaid…Never a Bride of Frankenstein

2. Sleep Study

3. H2Oh Oh

4. Fall

5. Moohead

6. Milk and Cream

7. Patch

8. Scratch

9. Road Trip

10. Tape

11. Enlightened Nonsense

Deirdre’s work is a kind of departure for what cannot be rehearsed in life. The artist performs in each film. This work is too important to be left to others. She never leaves the stage of the frame, and never speaks, she lets her body do the talking. She shows, demonstrating the cost of living in a body. She offers us the trial of ideas and their execution, her skin appearing as a book, written over and over, and without end. Perhaps the collection of our habits is what we call personality.

Sometimes she needs company. She doesn’t invite someone else because there is no way to share this making, this reproduction. She is giving birth alone. But still she needs company. She finds it not in other people but in other pictures. She speaks as a picture to other pictures. An advertisement for Jello. Broken glasses. A bed making and unmaking itself. A mother speaking to her daughter.

“It would be a lot more convenient if we could talk tomorrow unless it’s something very very important.”

I imagine a film portrait of a friend. I will photograph only the most typical of his activities. Every day I will shoot him shaving, brushing his teeth, washing his dishes, eating. Using video technology, viewers will be able to swap their face for his, trade clothes, remap genders. In this way, it will become a portrait of everyone who looks. It will be a study of compulsion and repetition, not the highlight reel, but the things we do every day. Our selves.

I don’t see much art anymore, I just don’t have the time. I make appointments with my friends the way galleries book exhibitions—many months in advance. When I make it to a show, I look at everything as quickly as I can and tick it off my list: groceries, keys cut, gallery, call mother. Of all the things on my list, art is the only one that reminds me, constantly, of how little time I have left. So mostly I’ve stopped going. It’s too depressing.

Enlightened Nonsense is one film in ten parts. Or ten films in one part. There is no dividing them now. They have been married, so even as they draw to a close, they get nearer to the place where they will begin again. Somehow this comforts me. I leave the gallery, knowing she is still there, unwrapping and falling, drinking and scratching.

Originally published as: “Monologue of the Body”, Mix Magazine Vol. 26, No. 3 Winter 2000-1

Why Not Always? (2005)

Beauty

My twelve year old nephew Jack doesn’t have to work at it, that’s the first thing. He doesn’t have to pretend or get all juiced up in front of the mirror or put on his fancy pants. Nope, he just strolls out in some forgotten piece of denim breathing hard because he’s still got adenoids that won’t quit so he always sounds like he’s just run up a hundred flights of stairs and his hair looks like he’s lost another wrestling match with the raccoon that lives behind the tree that he likes to throw strawberries at but it doesn’t matter. Jack still looks like the sun woke up in his face. Shining and perfect and looking back at me saying, “What?” or more usually, urgently, “Let’s go!” He is always in movement, never looking back, or forward for that matter, there is only the abyss of RIGHT NOW which manages to swallow everything, I can hardly believe he recognizes me from one visit to another. Who are you again? He shares his beauty with most everyone else his age, it is his birthright, his inheritance, and he squanders it like the rich person he is. He doesn’t notice it and no one around him, me included, would have it any other way. It’s not innocence, that’s something else. Or some embodied nostalgia. His blonde hopes are an easy beauty, the accustomed kind that lives out in the light, where everyone can see it. It’s so familiar in fact, that no one really notices at all.

But there is another kind of beauty, neither quite so blonde or so young. It is the beauty mentioned in the early moments of yet another Marguerite Duras autobiography, her most well known book, The Lover. One afternoon she is met by an older gent on the street who approaches with courtesy and caution and then braves a remark on the author photo which shows her as a young girl. He tells her, “But I prefer your face the way it looks now, ravaged.” What kind of writer, I wonder again and again, as I look over this passage, would include something like this up at the head of her story? This one here, this bit of rot on the vine, this is me. What kind of merciless overlord is able to walk into the high noon of their life and let strangers stare? Everything round me has stopped me from making this approach, which is why I’m still busy repeating my mistakes, each of which manages, as the years pass by, to wear a slightly different disguise. Each is a variation on a theme of course, and the name I grant to my mistakes is also a common place. I name it love.

Movies have been designed from the very beginning to promote the beauty spots of our lives, the high impact thrill of a face. But there is another kind of beauty which is unafraid to lose the mask of youth. It is the beauty of witness, of a person who has returned from the frontier. What a gift this is, to be able to look into a face which has seen too much. This is our passkey to the labyrinth, to be granted admission to the very brink of what can be seen or imagined. This face, this look, carries it all, if we could learn to read it. If we would dare. These faces are a testament: I was there and I didn’t look away. I looked. I saw what it was. And now I give you the gift of this face which has looked. This is another kind of beauty, this beauty is a rare gift, and goes unnoticed for the very opposite reason no one sees my nephew Jack. Most can’t see the beauty in it at all. Perhaps because the pictures which surround us, which we can’t help reproducing, are busy teaching us to look away, to refuse the act of looking. “I prefer your face the way it is now, ravaged.” There is a cost to seeing for yourself, a cost which must be earned and won and earned again. This cost is very much in evidence in the work of Deirdre Logue. It is her beauty. I prefer the way her face looks now.

Prolific

Deirdre is not crazy prolific, she doesn’t knock one movie out after another, she’s just rolled out a new one and it is only, depending on how you count up these concerns, her second video, or perhaps that first one (Enlightened Nonsense) was really a collection of ten movies, which would make this number eleven. Or shall we count all these one at a time as well? I don’t know how to account for them. And besides that, they don’t look so different either. Already in these early moments of her making one could speak of a “body” of work. It all looks like it’s come out of the same eye, the same kind of living. She takes herself as its “subject” or at least, as its material. This work has fathers like Vito Acconci and John Baldessari who were there when video first started rolling across the heads of portable machines. If it was small enough to fit into a cab then artists could begin work. They could find something useless to do with this new medium, they could put their cameras in front of something that might stop the act of looking away for instance. Or try something else equally outrageous.

In 1969 videotape was a single ribbon of black and white tape that lasted half an hour and if you edited it, you had to cut the damn thing with a razor blade which would produce a large glitch smack in the middle of the image. So mostly, nobody cut, you rolled the tape, and when you stopped the camera the tape was finished. It was standard fare in those early days to make tapes that ran the full length of a reel, which meant shots lasting thirty minutes of what they used to call “real time.” Look at John painting his body green, look at Vito talking and talking and singing and talking some more. Thirty minutes of real time in black and white, SONY hadn’t figured out how to turn the world into colour yet, and the microphone was a little pimple molded into the body of the camera, a crappy little thing which was situated for maximum camera noise delivery and forget about adding music or anything later. What you see and hear in these tapes was what happened lo-fi style, what the camera was staring at for half an hour and I don’t believe that attention spans were any longer or shorter than they are now, so it’s hard to vouch for sure how many people saw them, probably not a lot more than are watching Deirdre’s movies. There is a line, a lineage. The way these early video thoughts are transmitted doesn’t require a direct hit, it’s all up in the air now, it’s part of the weather, you breathe it in you breathe it out and sometimes it takes root, sometimes the seeds fall and it all comes up again as bad copies or deja art vu. Doesn’t that look like the wheel of my car? But Deirdre doesn’t have to worry about that, sure her chops are express delivered from these earliest moments of video art but she’s found a way to live it and that means when the work is finally ready it arrives hard and clean and hurting, the way art is supposed to be. She’s not much for thirty minute shots though, she reserves her punishments for herself, so instead of dishing the long take she slices it all up into pieces and then joins the data files in the computer until these so many moments are one movie and then she calls it Enlightened Nonsense (2000) and now, five years later, Why Always Instead of Just Sometimes (33 minutes 2005).

Let me run through it one section at a time, like the rooms in a house. Let me describe the décor as I get to it, as it gets to me, crawling up inside, rooting there. I can feel these roots, they come from a long time of living, of seeing and being seen, of waiting until the object looks back and sees you.

Per Se

It should begin in close-up with a face, her face, what else? Up close and personal but not too personal. When she gets as close as she can get without turning into a blurry haze she confides, “What I really want to say is private.” I believe everything she tells me though perhaps it’s not a question of believing. Clearly she’s performing for the camera, but this is the kind of performance where the more obvious the contrivance, the more abundant the signs of reproduction, the more raw and life-like, even “documentary” the subject appears. That’s her alright. Putting on the make-up, striking a pose. Not that there’s any make-up here, but the camera is already an accessory, a prosthetic. It absorbs these words but also applies pressure, it squeezes them out of her, doesn’t it? Or is that me doing the squeezing, the one she will meet later without knowing it? The one she is preparing these words for, part of the unmet Others. Her audience.

Her voice is slow and muffled, though there’s nothing else competing for attention so it comes through alright. Every word is there, right there, it’s late so no need to turn down the traffic or the pop song accompaniments. There are no accompaniments, not at this hour, and that’s the point isn’t it? “We” are all alone here.

There are picture frames missing, the image jumps across gaps and discontinuities, it’s a small thing, the frame never changes, and it always shows her head, her larger than life head fills that frame, so every time these missing time capsules disappear her face twitch twitches across this missing moment like something nervous, like something that can’t quite keep the sweep of the clock’s hands from jerking across the dial. It seems so easy for everyone else but “real time” forget about it. She appears in a stuttering continuity because time is no longer running smooth here, it might have once but who can remember?

She appears in broken time with her face looming into the lens, it’s a bit too close, a bit too large, the soft focus doing little to hide the worry lines running over her face. She might have been ready for her close-up once upon a time, glossy and presentable, but that’s not why she’s turned her camera on. She’s not interested in that kind of beauty. She’s a performer and her theatre is the camera. Just let me do this alone, and then you can see what it is later. I’ll show you later. The audience.

The face that appears in front of us looks tired, let’s admit it right here, we’ve hardly started and she looks worn out or worn down, or worn away. “I must have been that tired once,” that’s what I think when I watch her face looming like that into my TV screen. “She looks as tired as Jean,” I think, who is my personal gold standard for fatigue. Jean runs a documentary film festival in Switzerland and he runs after fatigue the way others chase stock tips or cruel men. It’s not simply that he stops sleeping for two or three days. Or the international travel. Or living out of his lap top. Or seeing more than 3,000 movies each year. Jean is always leaving, always late, always needed somewhere else at the same time, always busy doing two and three things at once. Perhaps he’s greedy enough to want to live two or three lives, or perhaps he’s running from the one he has. But when I see her staring into the camera I can see something of Jean’s face in this face. (This movie, I realize all of a sudden, is also about portraiture: how to produce a picture of a face.) This fatigue is necessary for Jean to defeat the habits of sentimentality and cliché which the monoculture tries to impose. As a result, while Jean may be distracted, his mouth is not a Hallmark Greeting Card. From the haze of, “It’s too much, I can’t take another step,” he invents himself, his moment, his encounters, again and again. He leaves nostalgia and the laziness of the word “God” (or Allah or George Bush) behind in order to live in something like the present. In other words: he uses his fatigue in order to make an approach, in order to produce a picture. He invents the present by producing a picture. He defeats habit through fatigue. When he is sleepless Jean is as large as a city, he opens his heart, at last he can see again, every nerve burning, slowed down in the every day catastrophe of too much. This is also how Deirdre arrives at the beginning of her movie, peeking out from the rubble of her experience. Talking. She is talking to us. What is she saying?

“And so what I really want to know is how I can say it even though it’s still private and you can know it without me telling you per se. That’s what I want to try to do. Then I will have something that you can take away that will give you a sense of me without actually knowing who I am per se.”

Per Se is the opening movement, the welcome mat, the establishing shot. Here we are, inside her face, her words, this monologue of negotiation. Something has already happened, the offscreen space is full of events which underlie this one, only the reaction shot is public, the rest, she insists, she can’t say. Or won’t say. Per Se makes a linguistic bridge between the “inner” life and its persona, what can be rescued, admitted, in this refusal of a confessional, this meta confessional, there are no lurid secrets here after all, only the lurid revelation that something has happened which we will never know, which she may never know, and its trace lies here, in this speaking. This listening.

“The scene is interminable, like language itself, it is language itself, taken in its infinity, that ‘perpetual adoration’ which brings matters about in such a way that since man has existed, he has not stopped talking.” (Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse, Vintage: London, 2002, p. 207)

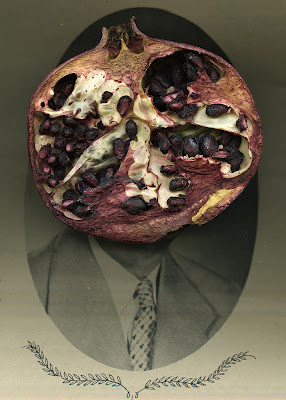

The object is speaking. The object of this face. The trail of her fatigue (the trail which has led her, surely and surely, to this very place) is written plainly on this face. (The face which demonstrates fatigue, which stages fatigue, which looks through fatigue in order to find us (the real secret, the audience, the strangers, the one she can’t know). The object is speaking its sub text, defining its limits, the refusal which is also an admittance. I love you by refusing you. I am push-pulling you. When you are far enough away you will be close enough to touch me. Her face might be a bruised fruit core on the sidewalk, a mark burned into photographic paper. If these objects could speak they might say Per Se. They are all tokens of a mystery which cannot, will not be spoken.

Is this what she is trying to tell us?

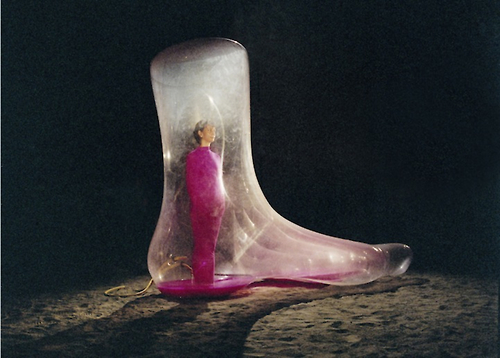

Under the Bed

Where do we look for our secrets? Under the bed. After Per Se the second episode of Why Always Instead of Just Sometimes starts up. It’s done all in one shot, in real time, the camera perched low to the ground looking up at a big double bed. Deirdre enters screen left and lifts the mattress away from her boxspring and crawls into it, slowly making her way across this sandwich of a bed while a metronomic electro rhythm chirps lightly away. The room is a paradise of kitsch, the sheets are gaudy bouquets of orange and red flowers, a black velvet clown painting hangs on the far wall. Yes, a clown painting. And to complete the domestic scene, a cat sits on top of the mattress, jostled by the artist’s movements below, shaken not stirred. When I saw it the first time the room rose up and kissed the screen, affirmative, this is what we want. Never mind that film students are still being told: no cemeteries and no pets, this is a crowd pleaser, this cat has maximum cute appeal, there is no stern performance artist at work here. It’s a short trip, perhaps it lasts a minute or two, but nothing like the pilgrimages that once awaited those seeking miracle cures for their afflictions. This is a quest parody re-rendered as domestic trial, a Martha Steward footnote (“And for you performance artists that like to work at home…”). Anti-heroic. Ironic. And clumsy. It’s important, somehow, for Deirdre to maintain this clumsiness, even this quick crawl doesn’t have a moment of grace in it, or dignity or elevation. Instead Deirdre has to get down on her hands and knees and genuflect her way through this bed with her limbs sticking out in awkward places while this sugar mountain of a resting place heaves and jitters and shakes. Parody of a sex act? Acting out underneath the covers? She is going where we cannot go. She sees what we can’t see and she’s not bringing it all back to us. We watch her take the trip and that’s as far as we can go. The only people who see what she sees are the ones who take the same trip. This kind of looking is not for tourists. At one moment, her legs still sticking out of the mattress, she pauses, has she found something, is she looking for some thing after all? But then she pushes on and the bed closes.

Why did the performance artist cross the road?

Repair

The third episode is entitled Repair. It shows a pair of hands taking apart a pomegranate and putting it back together again. Presented as a simultaneous view with alternating titles which read, “Make Mess,” “Clean Up Mess,” in a stenciled font. The two actions are interdependent, if the fruit wasn’t taken apart it couldn’t be put back together again. The fruit is made whole again utilizing the simple technique of playing the same footage backwards. A final title (issued as a challenge? A plea?) reads: Repeat. This compulsive reflection of compulsion hopes, above all, to repeat itself. To repeat itself.

There are things I can’t help repeating. Like the way I look at you, the way I can hold you with a look and then let you go. Call it a learned response, call it personality. I don’t need to banish you to the furthest corner of my kingdom, I can just stop looking, that’s all, that’s all it takes. One moment you’re here, you’re front and centre, you’re filling my eyes, my attention, and the next moment who are you again? It can happen that fast. I don’t think it’s a bad habit. It’s the distance between us, that’s all. It comes and goes. And then it comes again. What are friends for?

In Deirdre Logue’s Repair only her hands are visible. The movie shows a life of hands, it is hand-held, hand-made. The footage, I can’t help noticing, has been hand-processed, the strips of film unspooled and soaked in baths chemists call solutions. There are marks and scratches, solarized flashes, satisfying analogue surface noise that serve as reminders of film’s dual (two-handed) status. In the hands of its maker it is an object, a material fact, but for its audience it is only light and shadow. The film audience is always sandwiched between pictures “going on behind their back” and the pictures in front of them, projected phantasms of light. Logue’s rough handling of the material asks us to look over our shoulder, back to the place where pictures come from, where they are turned into light.

This miniature, like so much of her other work, is a synthesis of traditions. Minimalism, body art, underground film.

Logue uses her body the way a painter uses pigment, to provide the first principles of composition, but also: as an analogy of living, as the wound of living, its evidence and grieving mark. Whether falling in Fall, or licking a road in Patch, or peeling tape from her face in Tape, the body demonstrates the punishing trials of its repetition. This is Logue’s first tragic principle: the body is condemned to repetition. A motif underscored by her looped installations in gallery settings, where they repeat all day, in all the visible hours of the gallery’s life. As long as they can be seen, they can be seen again.

But the body’s repetition is not exact, it does not adhere to digital codes where the copy is the original. Instead it performs its repetitions as theme and variations, if one looks closely enough, inside each repetition there are small differences (the way we wash the dishes, brush our teeth, shave and shower, sleep) which may bring pleasure or pain.

Condemned. Is that too harsh a word to use? When I see this work I am reminded, again and again, that I am condemned to living in a body.

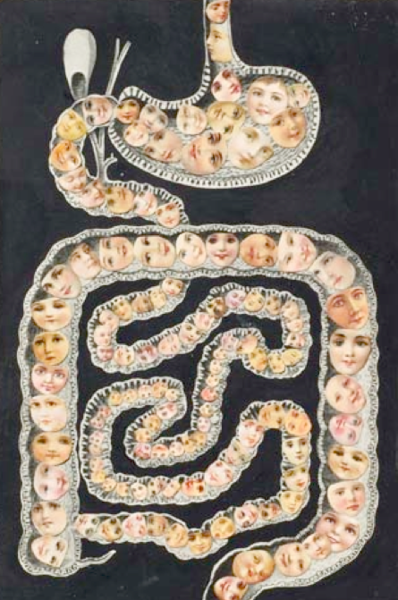

Sometimes two hands are not enough to show the work of two hands. In Repair we see only two, but they are multiplied. Logue superimposes the same two hands, performing the same action, on themselves. There are six hands altogether, pulling apart the pulpy interior of a pomegranate, then putting it back together again, or trying to. It looks disturbingly like cranial matter, shapeless in these hands, there are no corners or edges left, nothing one could lay a foundation with, nothing to be stacked or graded or separated. The undifferentiated mess she claws at has no centre around which the original shape can be re-formed, which underlines the futility, or at least, the endless nature of her repeating. A compulsion which feeds on itself. Which admits only that part of the world necessary for its repeating. The empires of prohibition which make prolonged depression possible. Errors in judgment which change a life, just like that, the small shifts which turn pessimism into hopelessness. The things you see or experience (please father, not there, never there) that can’t help repeating, compulsively, turning over and over again, in the memories of our body, in the memories our bodies are busy becoming.

In Repair only her hands are visible in the arena of the frame, the site of public disclosure where this body enters to show itself, to show us, the cost of living in a body. Over these hands, like a reminder from the super ego, an after thought, alternating titles which appear stamped over the image: MAKE MESS. CLEAN UP MESS. Like the hands which fill the screen, the titles come in pairs. They also repeat, ensuring in their on/off nature, that whatever one hand will accomplish, the other will take away. (On the other hand every movie has its last word, in Repair the last word is: REPEAT) They appear to work at cross purposes, canceling one another out, but only apparently. What they ensure is that the work of these hands can continue, and without end. The hand which cleans up the mess relies on the one that produces the mess. The two hands are parts of one another, an alternating current, relying on their opposite, so these two hands in Logue’s picture world become an image of perverse symmetry, of wholeness.

Crash

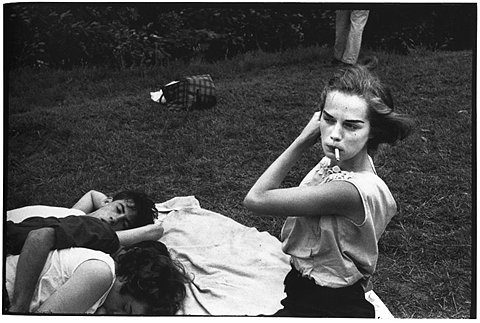

In Crash a pair of tots wearing raincoats ride their tricycles into each other and fall over. Superimposed on the background, a circular (repeating) pan of evergreen trees float by. A series of titles are superimposed which read, “I am 38 years old/It occurs to me now/that I may never get/a driver’s license.

What are we presented with here? A moment from childhood, looped and replayed (like a compulsion, a wound which continues to open, eternally). But this wound is played for laughs (this fragment might be named “Just Kidding”). Perhaps it is the same image that collides into itself (the collision is an act of reproduction, the fall is real enough, or momentarily real, but the over and over is an act of memory, of memory being applied to a moment, unable to let it go. Or is it the other way round? Is the event itself unable to let go?) This moment, this movie, has been reconstructed as a collision as if in answer to this riddle: there is a large field, a small girl and a tricycle. How does she manage to bump into herself? Yes, perhaps it’s the same image which collides into itself, this is one little girl who is her own worst enemy. She keeps getting in her own way. She falls, and while the descent is not far, it occurs often. She keeps getting in her own way, but try as she might, she can’t stop. She’d like to stop but the footage is finite, the personality is finite, and the time is so very long. As long as the rest of your life. The shot, the personality, needs to be stretched over this very long time, and that causes repetition. It’s remembered, and what is memory if not repetition, if not over and over? (Though this pretend trauma, this over and over wound, is not an image of the trauma, but only a place marker, the place the trauma belongs if it could be shown. But it can’t be shown. In place of the unrepeatable, the terror, the thing which should never ever be made into a picture: this slapstick repeating, this audiovisual stutter. Will it be enough to open the door?

Suckling

An image that is hardly there, grainy and dark, finally resolves into another close-up of the artist’s face. Not: oh, it’s her again. But instead: this is the material out of which I am making my art. In place of pigment and canvas, the artist’s face. She is sucking on her fingers which plunge into the open wound of this face again and again. A theme with variations (if I did the math, timed the intervals and assertions, would I recover the momentum of the Goldberg Variations?) It’s not purposeful, there is no destination in this traveling, no destination home. She has a ring (or is it a tattoo?) on her middle finger. Probably it’s a tattoo. She fills her mouth with it, her mouth swallows the fingers, the two sides go back and forth again and again. After all this time: a return to mother.

“Only the Mother can regret: to be depressed, it is said, is to resemble the Mother as I imagine her regretting me eternally: a dead motionless image out of the nekuia; but the others are not the Mother: for them, mourning, for me, depression.”(A Lover’s Discourse by Roland Barthes, Vintage: London, 2001, p. 195)

Suckling shows an image of putting the body back inside itself. Of folding up the body, tucking and sucking, and incorporating. Nothing will stick out. There is nothing extra or left over. It is also an image of retraction: I take that back! That hand, this elbow, this thigh. I am disappearing into myself.

I am sustaining myself with myself. I am all I need. Aren’t these the words he used, repeated (like a compulsion) day after day? Take eat, this is my body. And she does.

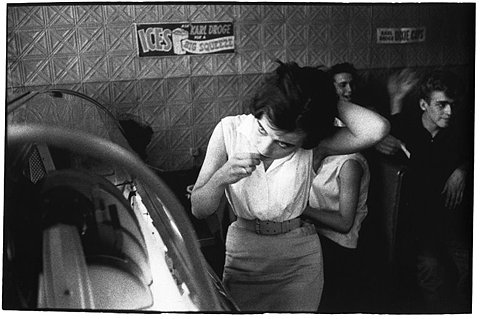

That Beauty

That Beauty is another performance short about the beauty which can exist only over there, belonging to someone else, or in the past, or to come, that once and future beauty, but not now. That Beauty takes as its subject the listening body, driven by ears not eyes. The subject, the dancer and artist and performer is wearing headphones which cut her off from the world (from the viewer), which remakes the world as her world, though she is already part of a received wisdom, the song loop for instance which issues on the soundtrack, which I (we?) imagine are similarly rising into the headphones. They are not her songs, though they are directed at her. She is a headphone solitary, the phones driving her inside the body, pushing the music inside, turning the body into music and rhythm. The song occurs in a loop, turned back on itself, asking us to play it again Sam. The chords swell and then a male voice speaks/sings: “That beauty right there.” The music stops under the force of his pronouncement, the singer picks her out, singles her out from the crowd (the crowd is also the music, the crowd parts, the music stops). His voice is also a kind of look, a finger pointing RIGHT THERE. Meanwhile, in pixilated abandon, the performer dances on, apparently “all body” reduced (lifted?) to a symptom of sound, an effect of the locked groove, hips swaying, throwing her hands up in the air, smoking while she’s shaking, she’s feeling as good as it gets. And if it’s filled with fear and anxiety and pain, well, that’s all part of as good as it gets too.

She films herself as a high-contrast silhouette so we can’t make out face or expression, underlining the fact that she is a body. A body held in thrall to a beat and a voice. That beauty. That voice an idea of beauty. Or in Logue’s re-draft: that abject beauty. The words onscreen appear as superimposed intertitles, answering the man’s call, as if from the dancer’s mind, the mindless mind, the carried away, overcome, overcooked mind of the headphoned solitary. The dancer who is also a writer as it turns out, filling in his sentence, projecting, saying what he (the imaginary one, the suitor, the one who is out there right now waiting for her) cannot say. That beauty right there (he says) “FEELS FRAGILE” says the title. “FEELS ANXIOUS” answers the title. The emotions run from fragility through shame, invisibility (is invisibility an emotion? The first emotion?) and then finally forgotten (I’m nothing, never was, no place for hope to cling to). The body responds to its suitor the only way it knows how, by re-staging its past, over and over, with everyone who encounters it, until it can be absorbed, and let go, condemned to repeat until the record stops.

The body is mostly made of water, and here, in this one minute body brief, it’s all about the body, it’s about water, inside and out. The movie begins and ends with water, the dancer appears inside this wash of surf and crest and foam. Rising and falling and easy, it goes down so easy. She never leaves her kitchen.

Touch me if you must. If you dare. But know that some have entered this house and never left. You may meet them on your way towards a door which no longer exists. I hope you like it here, doesn’t matter either way, just makes it easier.

Wheelie

Wheelie features another home movie loop. A young boy, five or six, pops a wheelie on his bike (he rides on the rear tire, while “popping” the front tire up in the air) and then falls off of it. He lands on the ground though his bike continues to move forward, borne along by its momentum. Here is another country setting, the footage turned a strange colour owing to the age of the film, the colour dyes have shifted in the heat and cold of the years between producing the look, the glance that made this memory possible, and the stare that returns it as a fixed item in a personal image repertoire. The superimposed titles read: “I am 38 years old/Although I still make mistakes/I have found/more people/to blame.” Wheelie is a slapstick of rising and falling, of modest ascent and abandon, met almost immediately with a coming to ground, a grounding, a fall to earth. Just kidding of course, but even kidding leaves behind a reminding bruise.

Band-Aid

A title announces the end of part one and the beginning of part two. All in the dark. Part two opens with a close-up shot of Deirdre wrapping her fingers and hands in bandages. The image is sped up, though still synchronous, imparting to proceedings a restless, nervous intensity. There are no visible cuts that need to be salved, the entire hand is a wound, this body is a wound, there will never be enough band-aids, she needs all the protection she can get, though it’s still not enough.

And of course this sequence is about repeating, like all the rest. About the compulsions of the body, the compulsion that is memory (We are going back, again. In other words, returning to the body.) She doesn’t put the same band-aid on the same hand, but it’s the same kind of band-aid on the same hand. Over and over.

The band-aids are a covering, a second skin. Now you see it, now you don’t. The hand exerts a “grasp,” it “gets a grip.” The hand is the moment of the body related to metaphors of control. What does it mean to cover up this control, to bind it? Is this not another way of saying, I don’t have a handle on it, I’m losing my grip? “Get a handle on it.” That’s how the saying goes. But what if there is no handle? What if the riddle doesn’t arrive with handles? What if the body you really want has no orifices, no place to admit the outside, what then? And worse, what if that body is your own?

A helped hand not a helping one. A pointer to show how tender, how vulnerable this hand is. How raw the “first” skin is. This covered over hand (but not hidden or put away, it is right there in front of me, in close-up. The wound is examined, pulled at, fascinated.) How much longer? That’s what I wonder when I watch this. Will it go on and on? Will she stop at her hand? Wait, she’s covering her wrist, perhaps she’ll do her entire arm and the body attached to that arm. While she applies her elasticized scars, disposing of their plastic containers by dropping them out of frame in a steady heap, I wait for her to cover the tip of that middle finger, and a moment of exposed palm. The longer the shot goes on, the more I am seeing her hand the way she sees it. Don’t stop now, you might miss a spot. This is what I would like to whisper into her ear, in order to urge her on. Not that she needs urging. Don’t stop now or ever. And then it ends.

If there is no possibility of contact, of pleasure, or the pain which pleasure makes necessary, which deepens pleasure and allows it to ripen, at least I can make a sign. At least I can show the other one, the one who is trying to touch this body without orifices, that I am still here inside the fortress. If I can’t touch you it’s because I don’t have hands anymore. Look. The artist is making an image with nothing more than a box of band-aids and two hands. Christo is busy covering the Reichstag, and that is another history of division, Deirdre begins at home, covering her own hands.

“Upon it we sleep, we are awake, we fight, we win and we are defeated, we seek our place, we experience our incomparable happiness and our astounding falls and collapses, we penetrate and we are penetrated, we love.” Gilles Deleuze

Worry

Worry is another home movie brief, showing (parts of) four very young girls dancing. The girl in the foreground has her back to the camera and turns to face us, as soon as the turn is complete the shot ends. This takes about four seconds. Superimposed titles appear three times, bearing the same message: “I am 38 years old/and sometimes/I worry so much/I worry/it will kill me.”

The loop is so short there is no time for a social relation to develop between the four figures onscreen. Instead they become part of a rhythmic churning, which is centered on the act of the girl in the foreground who reveals her face. She is overexposed and grainy, the original made with cheap home movie equipment, so there is little detail in her face. We sense a face, she gives an impression of a face, but no matter how many times she comes around, her turning leaves only an impression of an impression. There is no gain, no addition, in this accumulation of a moment, which echoes the “worry” intertitles which are caught in a tautology of worrying (she worries about worrying).

The use of old home movies asks: was the worry already there? There, right there, in this moment which can be played and frozen and slowed under an adult’s supervision. Is this the origin, the primal moment of worry? Even if it is, the artist suggests, we wouldn’t know. Look at the face—it doesn’t tell you a thing. It’s blank, project if you will, if you must. If there was a face that could appear in this turning it would be here, perched right on top of these shoulders, but her face hasn’t occurred to her yet, she is not turning to reveal herself after all, only to show her secret, to show the place her picture would be, if she had one to share.

Eclipse

In Eclipse the artist appears in night vision mode, black and white and blue. Once more Deirdre is looming into a wide angle lens which bends her face around the glass. She moves her cheeks around trying to get them to make a sound, to crack her jaw. “Can you hear that? It’s like a crack. Did you hear that? Oh here comes somebody.” Somebody, I wonder? Deidre is sitting in what looks like a domestic setting. She appears (again) as if the party’s over and everyone’s gone home and her lover’s in bed and in this exhausted state she’s begun (again) to speak with her camera. To perform herself. “Somebody,” she says, though surely she has to know who this somebody is. Her lover, her best friend, one of her parents maybe up wandering sleepless after a night of too many thought balloons. But for now she preserves this secret, this secret place, for now it’s just us. The artist and her strangers, the ones who will come later in order to bear witness, to complete her with a look, with our attention, though we will arrive too late, when the moment the image could have arrived has already past. She invites us but only too late, we can find her only after she’s gone, and we are left not with a picture of what she’s done but of what she can show us after the action has taken place. It is as if we are watching the civil war in the Gaza Strip but we need to read it all, and without commentary, from a single face sitting at the window. And it is not happening live, it has already happened. They have already killed the rest of the family, bulldozed the neighbour’s house, destroyed the school. The next day there is a face at the window. This face bears the mark of all that has happened, and though we can’t read the specifics of what has occurred, the artist hopes that something else can be conveyed, some manner of facing the unfaceable, of standing at the brink of what cannot be shown, between the two worlds of the visible and the invisible. It is a dangerous place, no wonder she looks tired, and stretched out of shape, no wonder she is cracking up, falling apart, celebrating her fissures, her openings.

“Oh here comes somebody,” she says, and before “somebody” comes in, the camera pans down to the ground so it’s not pointing back at her face. So it doesn’t look like she’s doing THAT again. Then there is a cut and she is starting again. “Ow. Can you hear the cracks? Did you hear that? Did you hear that? Can you hear?” While she is speaking a dark, shuddering shape appears on her cheek, not quite circular, it changes shape as she moves, a dark hole added via the magics of video special effects. Once again the image the artist offers us of herself is unflattering, not quite grotesque or gargoyle-like, nonetheless she frowns persistently, her face is bent and misshapen, she appears to be in distress. And then there is the action itself which is repeated, like every action in each of these vignettes is repeated. Now she is pursuing the cracking of her jaw. It is the sound of a body under duress, the skeleton protests, rubbing against itself. The body is an instrument for producing sound, not only the familiar sounds of language but the protest noise of age and failure. “There is a crack in everything,“ Canadian poet Leonard Cohen sings on his disc The Future, ”that’s where the light comes in.”

Alone, at night, she sounds her cracks and fissures. Is this an image of the artist at work, running her fingers over the fault lines, worrying them, unable to let go, letting the furrow run deep and deeper so that some uncomfortable and unbearable truth might emerge? She will go where we cannot, and she won’t bring back the story of that place, because there aren’t stories left to tell. The myths are dry, the mouths are empty. But she can show us the cost of the travel, she can show us what it means to go this far, to look from this face.

Blue

In Blue a split screen shows the artist blowing up a paper bag and letting it deflate, in close-up of course, on small opposing screens. The bag almost fills the frame when it is fully extended, a measurement of breath (for the Greeks: spirit, in modern parlance: Esprit, the globalized chain fashion store). The breaths are counting moments, making a slow addition. How much and how far? Each breath fills the frame with its exhaustion, the repeatings of its hope, which is the same hope, to go on and on, to remember, to give and receive. But the bag (which provides evidence of her journey, which produces “the image”) also stops the outside from entering her. The outside world doesn’t enter the artist, the artist applies her attention to the world. The artist enters the world with a frame and admits only those moments which fit inside it. It is a small frame and a small world. All too soon the artist is breathing their own breath, locked into their self-created system of knowing. What can come in, and what can come out? What can be shown of the outside? And what about self expression? Only the reality of the container is possible, the way experience is staged, only the stage itself can be shown. The main show has already happened, or has been buried in a necessary forgetting that the audience is already a part of, which the audience, the very fact of witness, of coming later, of surviving the too much of it, the audience makes this forgetting necessary. Blue? Well I guess so. Unable to get beyond your own bag (of tricks? In the hipster parlance of the beat generation a bag was your concern, your attention: What’s your bag?). Unable to get beyond your own bag either to achieve self expression or to admit the world, here again is a body without orifices, a sealed off body, closed except for this demonstration of its frame or stage. Is it enough?

Beyond the Usual Limits: Part Three

Black Ear

She’s close again, when the camera is on it seems she’s always there, right there, filling the frame. Her face is the material this suite of fragments is built up out of. Now she appears in the daytime, on her porch perhaps, or out on the driveway. The look on her face shows her concentrating, no messing around here, it’s important to get this just right. She uses the video monitor as a mirror, to show her what she’s unable to see, extending her look through a vision prosthetic machine in an echo of the Vito Acconci tape where he shaves the back of his head, following the image in the monitor. He performs an action on himself relying on the camera to reveal moments of his body that are otherwise hidden to him. He follows the machine. She follows too.

She begins to apply black paint to her ear, one small stroke at a time. In Eclipse a dark video glitch inhabited her face, now this abyss has become a consciously applied mark of separation. The ear is highlighted, marked off and zoned, the place of hearing has become an image. (Or has it been disappeared? Blacked out?) When the ear is completely black the image cuts and reverses Deirdre’s features. Now she wields the brush from the other side, and patiently undoes the painting. This scene reruns the first half backwards. “I take it all back!” It shows a world without consequences, where marks can be made and then withdrawn, as if they never happened at all. Here is my longest running fantasy brought to life—to return to my kindergarten self knowing everything I do now, to live a second chance. To be able to return to each moment in my life having already run through it the first time as a dress rehearsal. How satisfying (or so the fantasy goes) to be able to combine that unformed body with a mind and emotions that are still trying to stay above the water line in the present. But of course when I go back, or so the fantasy goes, the waterline would be far away, every dialogue delivered with more panache, the jokes a little sweeter, the timing tighter. Above all the abiding fear which has become such a reliable companion could be swapped for this double take, this eternal return (bearing in mind Marx’s dictum: that everything in history appears twice. The first time as tragedy, the second as farce.)

I run my life back and forth across the tape heads, undoing remarks, softening the lighting until I can come up with a version I can stand to look at. This doesn’t take long, I’m not worried about a precise memory, only a bearable one. Imagine cutting all your vegetables while never looking down, my memory is similarly a rough cut, an approximate assembly. Sometimes I pour attention into a moment, like my ear for instance, and then it falls off and I have to begin all over again.

Making an Approach

If I knew what I wanted I wouldn’t be in the movie theatre tonight, looking for more pictures. I need these pictures to say what I can’t say, to show what I can’t even begin to think about showing. These are small moments of taking heart and it’s working, I’m encouraged, I want to go on repeating as well. Knowing it only again and again. Knowing that by coming here, by standing in front of these pictures, I am taking my place inside one of Dante’s circles. Every oppressor requires their victim, and I have come here, happily, my arms raised in surrender, my eyes open. I am ready to begin again, or middle again, reduced to a pair of eyes, not wanting to take responsibility for what I see and yet. Not wanting to account for what I saw and yet. “No one said it would be easy,” my mother would tell me, and I couldn’t wait to meet this new person, this “no one,” but I never did. Not tonight, not all those other nights and going back wouldn’t change a thing. Sometimes when I get up in the morning there is an arm missing, or a foot, an eye. It never lasts for long but the journey is not an easy one, from one part of the night to another. I will turn my tables back into forests. Stop trying to think more than one thought at the same time. Make an approach. It is time, past time now, to try and make an approach to the image. I will fail of course, the artist has shown me what it means to fail. She succeeds through failure. Failure is the portal, the entrance, the beginning of her work. Her videotapes, still so very young, are a cornucopia of failure. Let me count the ways. I will fail too. Falling down eight times, getting up nine. No need to worry about that any more, the marks it leaves behind are conversation pieces. Openings for strangers. For you.

A support letter to the Canada Council for Deirdre Logue

To the ones who can say yes or no

I have known Deirdre for a dozen years, as an artist, and a central driving force behind both of Canada’s largest and most important media art distributors, and a pair of media arts festivals. It took her a long time to get started, in part because she is an unexpected and unusual traditionalist. She absorbed the his and herstories that landed before hers, and only then etched a definitive mark that was at once recollection and summary, and all her own. Her work returns to the first-person stage of early video art as keepsake and promise. They are monodramas staged for the camera. Her body is used as a material, the same way an orgami maestro would take up a sheet of paper and create a gesture out of it. She produces pictures with her body, and I think this is the most difficult bit to get around for some viewers. These pictures might look like they are pictures of her body, and that’s true, but it’s a secondary truth. Using often obsessive and repetitive gestures, she creates a picture over time, using the material of her body. This is, I think, the heart of what performance art is on about. It is not theatre. It is not an exposition of, or demonstration of. It is a picture, which moves through time.

What kind of pictures are they?

Nothing happens for the first time, it only happens again. Getting hit by a ball, for instance. Why am I still so attracted to getting hit, is it so difficult to move out of the way? In order to do I might have to crawl under the box spring, where the secrets are (it hurts to go down there, to make this passage, to learn these truths). She covers her arms with comic book stitches, it’s a joke, she is her own Frankenstein, but even in this playful aside there is a feeling that what belongs on the inside is being shown on the outside. In Milk and Cream she shows how a good thing turns into a bad thing. These are long love stories, lived and pored over and talked out, then shrunk down into a four minute action for camera.

She is taped up and drowned, sleep deprived and scarred, and in each of her bodily vignettes she continues to offer us some hard earned fable of understanding. This is how long it takes, and this is how hard it is to get there.

She is invariably alone in her encounters, her only companion her camera prosthesis, which provides a duet of looking and being looked at. In each of her short studies, she offers us a reflection on our own looking. As the body regards itself, it offers us a portrait of looking itself.

In her new proposed suite of openings, she may extend the grasp of her solitary manoeuvers in two directions. The first will see her re-engage her camera eye with a variety of new perspectives, allowing the camera to enter her, to stretch and squeeze her body, to tug at it like a newborn, or someone at the end of their days. She has so far combined and collected her work into a pair of complex composites, this grant will permit her to trump each of them in the production of a third. But more than an elaboration and elevation of her own already sophisticated practice, there is the promise that the proposed work will migrate from the media art form and enter a more fully sculptural expression. Of course, the way she deploys her body to produce pictures is already sculptural (they engage a single shape over time), but the artist now promises to augment this familiar element with an ‘expanded cinema’ collection of notes, models and associated objects.

As an editor/author, I have been privy and privileged to include her genius texts on Frank Cole (in the recently published Life Without Death (Coach House, 2009), and Philip Hoffman (in Landscape with Shipwreck, 2002). How wonderful to imagine that the luxury of her imaginative writing could be given a space alongside her often wordless performances. Once again, she is busy following traditions in the hopes of making them her own. What would the work of Martha Rosler, Vito Acconci or Lawrence Weiner be without their accompanying texts? This necessary extension of her practice arrives at a critical time for this artist, who is already widely shown and celebrated, but is ready to take the next step into a more fully formed complexity. I urge your support for her, she is one of our finest and most necessary artists.

Mike Hoolboom

June 1, 2009

The Art of Eating (2012)

I am starting to see the pros to just working, never finishing… the experiment in keeping it all as everlasting and inscrutable, there and not there… (Deirdre Logue, email)

Is it too terrible to admit that I am not looking forward to seeing Deirdre’s new movies? I have other friends with penchants for high wire disasters. There’s nothing quite like making a big screaming mess when your heart — secretly seven times larger than normal size — lies exposed and trampled on. You think you’ve seen pain and heartbreak? I’m going to burn your house down. I’m going to hurt until every newspaper wire sings with it, until the news anchors declaim it and the courtroom judges nod in time. I remember visiting a Sophie Calle exhibition where the French artist filled not one but two entire galleries, floor after floor, with global reaction shots to a single break up letter she had received. You’re going to break up with me, motherfucker? With me?

Of course Deirdre’s self immolations are more modestly staged. She’s Canadian after all, and has spent most of her adult life in the artist-run centre world, where everything new and fresh and never seen is watered, and then left to dry on the shelf until the joints are creaky enough for career ending retrospectives and a final bow. We are a country that knows what do with the beginning and ends of our artists, what remains vexing is the problem of the middle. And here we are, in what amounts to a mid-career catalogue, surveying the middle distance, the middle way.

Deirdre is not crazy prolific, she doesn’t knock one movie out after another. She’s just rolled out a new one and it is only, depending on how you count up these concerns, her third video in seven years. Or perhaps that first one (Enlightened Nonsense) was really a collection of ten movies, and her second movie (Why Always Instead of Just Sometimes?) a jam of twelve, which makes this either number three or twenty-six. Or should we count all these one at a time as well? I don’t know how to account for them, and it seems I’m not the only one. There is still the business of her great and forever unfinished Rough Count (2006-ongoing), in which the artist picks out and enumerates each piece of confetti in a bag. She is roughly three quarters finished, and the installation, shown intermittently and always in expanding configurations (does this signal ambition or its absence?), is presently sprayed across no less than fourteen monitors. With more to come.

In all of her works, whether many or few, finished up last week, or many years ago, there is something instantly recognizable. Oh, it’s you. Already in the earliest moments of her making one can recognize a “body” of work. It all looks like it’s come out of the same eye, the same kind of living. She invariably takes herself as the work’s subject, or at least, as its material. Each miniature appears in a like-minded suite that features performances for camera. This work has fathers like Vito Acconci and mothers like Joan Jonas who were there when video first started rolling across the heads of portable machines. If it was small enough to fit into a cab, then artists could begin. They could find something useless to do with this new medium. They could put their cameras in front of moments that might stop the act of looking away, for instance. Or try something else equally outrageous.

In 1965 videotape was a single ribbon of black and white tape that lasted half an hour and if you edited it, you had to cut the damn thing with a razor blade which would produce a large glitch smack in the middle of the image. So mostly, nobody cut, you rolled the tape, and when you stopped the camera the tape was finished. It was standard fare in those early days to make tapes that ran the full length of a reel, which meant shots lasting thirty minutes of what they used to call “real time.” Look at John painting his body green, look at Vito talking and singing and talking some more. SONY hadn’t figured out how to turn the world into colour yet, and the microphone was a little pimple molded into the body of the camera, a crappy little thing situated for maximum camera noise delivery and forget about adding music or anything later. The received wisdoms of these tapes was low fidelity verité, the play and the replay looked pretty much the same. There is a Garden of Eden myth around video — like everything in our culture that lasts longer than a week — that attention spans used to be broad and deep and perfect, so no one minded these raw, undigested, real time experimentations. But if you go back and speak to the ones who survived the moving wallpaper and the anarchic willingness to share mistakes, it becomes pretty clear that homo videus wasn’t too far removed from their present-day counterparts, except that lacking a steady classroom presence, no one was forced to watch these long form masterworks. The truth is, audiences were reliably spare, and largely comprised, much like today, of an extended family of like-minded artistes and already interested parties. What I want to emphasize in all this is that on both the production side and the reception side, there is a continuity at work. Deirdre’s movies are part of line, a lineage. In that sense, however up to the minute they might appear, there is something traditional about them. They draw their restrictions (and Deirdre’s art makes a necessity and virtue out of her restrictions) from an understanding and recuperation of past efforts in the state of the art.