All in the Family by Mike Hoolboom (July 2013)

The first time I saw Daniel Cockburn’s movies they looked like they were made by Steve Reinke’s younger brother. Steve is a video artist, like Daniel, and when Steve started making videos, prodigiously and prolifically, he rescued the term. All of a sudden, it didn’t seem to be a default, basement-dwelling function to be a “video artist” any more. And perhaps it was at this same moment, I have to admit now, that everyone in the field was temporarily reorganized as Steve’s spawn. At least for me. There are certain moves that change the field, that change the very nature of the project, not only for a single artist, but for every artist.

I can’t tell whether I am saying that Steve Reinke is my father, or that Daniel is my brother. But this much is certain, Daniel’s project feels both familiar and familial. The tropes are well rehearsed, the designs clear, the genre conventions upheld. Another way of saying this is that Daniel’s movies are part of a tradition. There have been other makers before him, and some of their juice was so heavy, their stakes so large, that it became part of everyone else’s stakes. Of course, there are some video moms and dads who are endlessly rewatched – could you tell me that bedtime story again, the one I’ve already heard before how many times? – and this way canons of influence are created. In literature, these lineages run back over centuries of course, but the aims of media art are more recent, and wonderfully, at the present moment, the deluge of makings and makers threatens to obliterate the outlines of the field altogether. Only a couple of decades ago, the realm of video art was a collection of inner sanctums sprinkled across the world’s largest cities. Today, everyone is a video artist. The shift from clubhouse insider to being a speck in the digital crowd is an interesting moment to assert one’s familial ties. How does one attach to the bloodline (I am part of you), while maintaining independence (I am separate from you)? Perhaps an autonomous voice can only come out of a deep acceptance and embrace of the limitations of tradition. The question of belonging turns out to be the flip side of the question of self identity. Oh wait, that’s how T.S. Eliot put it in Tradition and the Individual Talent (1919). Maybe all I can offer is to let fathers run out of my mouth.

Why don’t we start again with a fragment from the artist’s dream life? It appeared in a book, so we can be sure it has been manicured and stage managed. This is how I want the unspeakable thing to sound, it should be entertaining, and story-like and funny. When Daniel recounted his dreams to me (I was not his analyst, but a client of his former video distribution services) it made me wonder whether he had somehow transformed the forbidden horrors of the unconscious into personal entertainments. Let’s roll Return of the Repressed (the sequel) with a laugh track and audience applause.

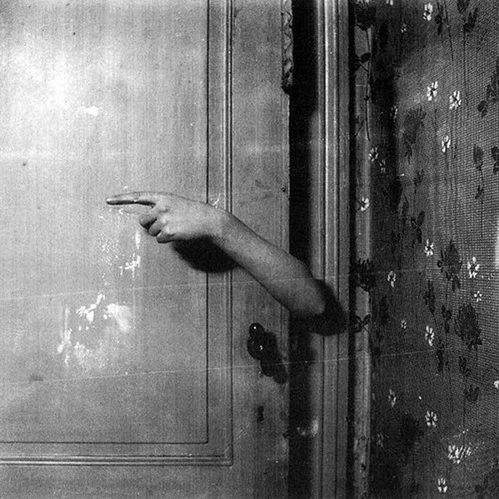

“…there was something terribly wrong with the world and I was the only one who knew about it. I found a mini-DV videotape in an alley and as I picked it up, the reels started to revolve, like in Starman (the TV show, I never saw the movie). Jeff Bridges could hold an audiocassette to his ear, telekinetically cause the reels to turn, and hear the contents of the tape. Now the reels were turning of their own volition, and I could not see or hear what was on the tape… but as I held it between my thumb and forefinger, watching the reels turn, I saw that the tape was slowly peeling a strip of skin off my fingers and winding it around the reels. I tried to drop the tape, but I couldn’t, because my skin was inside it. I worried this process would continue until I gradually lost all of my skin to the inside of this mini-DV tape… but some more tugging managed to snap the skin and I dropped the tape to the ground.” (Smartbomb: an interview with Daniel Cockburn in Practical Dreamers by Mike Hoolboom, Coach House Books, 2008)

He had told me this good joke of a dream, and then, like the proper student of the unconscious that I am, I promptly forgot it. Then he wrote it all out, word for word, exactly as he had first recounted it (how would I know?) so that I could forget it again until now, in a moment of re-encounter. We all have our roles to play. I think the dream narrates how the medium of video is reshaping Daniel’s body, even his life. In order to keep rolling, his skin needs to run through the tape cassette and over the playback head of the video machine. The medium is the message, and he is the medium, every part of him recast. The expression “tearing a strip” comes to mind, not least because this is how Daniel describes the way his finger flesh winds up inside the videotape. Tearing a strip means berating and belittling someone. Its origins lie in the British military, where strip refers to the stripes commonly worn on one’s uniform, denoting rank. Tearing a stripe off a uniform is an angry way of demoting someone, of displacing them by showing them their new place.

Is this a dream about becoming an artist? How else to become an artist, if not to dream about it first, to lay down the necessary psychic underlay? The dream’s message seems too clear: in order to become a video artist, I have to become video itself. When I look into the abyss of the machine, it looks back at me, and I am remade. My identity glitches and recodes, my look freeze frames, my memory rewinds, my hands tilt and pan. The vocabulary of my new medium, my new lover, has become the vocabulary that I use to describe myself. And like any new love, the meeting is catastrophic, painful, dangerous, seductive, and necessary.

Daniel describes the video wheels turning “of their own volition,” in other words, all by themselves. The medium is an independent agent, a hungry machine that runs on flesh, requiring the skin of the artist to feed it. Take, eat, this is my body. The machine tears a strip off the artist, it demotes the artist. If you want to enter this place, you need to let go of something, you need to be less of what you think you are. How do I say yes to this family, how do I enter this new art compact? I have a stripe torn off my jacket, I demote myself, as the cost of admission. In order to realize myself, to become who I really am, I need to let go of my favourite self renditions.

What interests me more than Daniel’s words are the ellipses. I guess I added these myself, no wait, I think these are also the artist’s invention, perhaps nodding to the vagaries of the unconscious, the impossibility of translation. What is buried in those spaces? What is it that cannot be said in this dark dream? “I worried this process would continue until I gradually lost all of my skin to the inside of this mini-DV tape…” What the artist fears is being skinned alive by his beloved machine. In order to keep rolling, the machine requires nothing less than the whole of his skin. To be newly exposed and raw, to lose the covering, the container, the surface. How do you look, once you’ve let the machine enter you? Without a hide, a hiding place. There is no place to hide. Is this what it means to be an artist, to give up all of one’s hiding places?

Many of video art’s first efforts were made with clumsily heavy machines that produced hazy black and white pictures and poor sound. Not infrequently, these artists might set themselves up in front of this low fidelity apparatus and begin to speak. Or at least: someone would start speaking. The camera allowed its subjects a voice, subjects could come to voice, realize their voice, through this machine. In the world of experimentalist movies on the other hand, talking was often discouraged. Photo-chemical cinema was “visionary,” a “metaphor for vision,” optically oriented for sure. If video’s low resolutions allowed it to function as an extension of ears and mouth, movies were an elaboration of the eyes. Back in 1999, one mystified audience member at Windsor’s Media City Festival put it best. After another punishing screening of silent landscape movies, out strolled another of Steve Reinke’s candy-coloured, post-pop confections, brighter, smarter, and harder than anything else in the room. In the requisite post-screening interrogation scrum he was asked, “Why do you get to talk?” In this world of difficult fringe emulsions, the place I used to call home, words were used by people whose pictures didn’t measure up. If you were clean enough there would be no need for language, or even editing. Steve’s chatty works flew in the fact of that unconventional wisdom, and offered us permission for new joys to root.

Of course, what Steve was doing, and what Daniel did after Steve, was to make a pilgrimage back to video art’s earliest moments. In order to go forward, it’s often necessary to go back. Just like video art’s moms and dads, Steve and Daniel busied themselves talking into the machine. Words were at the heart of the practice. But because they were good postmodernists, beginning their work in a new digital moment that created unparalleled access to already existing materials, they often combined their chitchats with so-called found (stolen) footage. And once you stare at it long enough, you learn the knack of shooting your own material as if it was found footage too. The rush of videos that followed were at once traditional and forward looking.

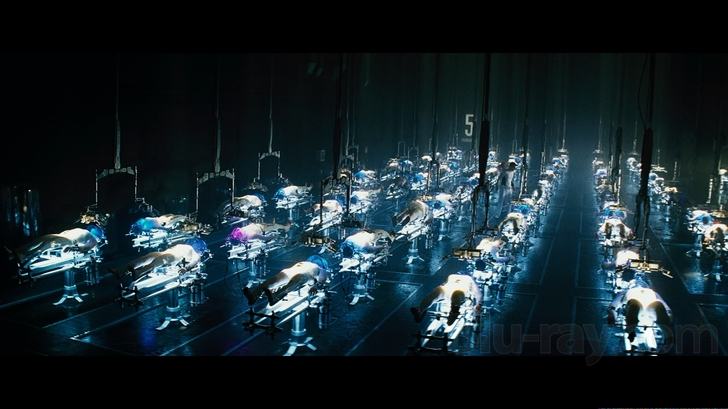

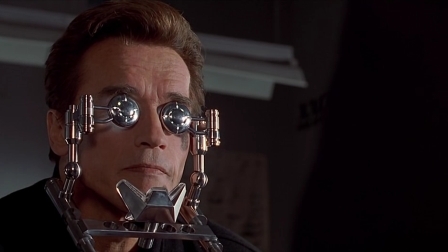

In his witty remake of the Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicle The 6th Day (2000), Daniel carves up the original into six new days of creation in order to impose his will on his newest digital son. Here, Schwarzenegger’s visibility and stardom means only that his exposure to the author’s interventions are maximized. The bigger the star, the easier it is to tear a stripe off him, to demote him to the status of video art subject. Arnold is recast as the lead in a video art movie, where heroic rescues have been abandoned, and there is no escaping the digital manipulations of his new father. In one bravura sequence his speech fragments are collaged together to force him to say: “You think you are a media artist because you control me with a piece of software. This is terrible. This is not natural. This is creepy. You know that. I want my life back. You think you are God because you control me. No, I don’t think you are God. I don’t think you are a media artist.”

In order to be a media artist, one must be God, the father, the one who controls. Or else one is the son, the subject, the controlled. In Audit 1 (3 minutes, 2003) Daniel attempts to create a single picture of the artist’s life by laying out repeated occurrences on a graph. “Every time I imagine what it would be like to beat someone within an inch of their life. Every time I see the word ‘moist’ in print. Every time someone speaks to me about hats.” What are we, if not the sum of our repetitions? Once again, the artist takes up the role of amateur scientist, searching for an underlying order so that he might give his own making a shape. The story behind the story, the summary recounting, arrives in the form of a second voice-over that cuts into and interrupts the list-making voice. The father pulls the graph into focus, he can see the big picture, the underlying form of forms. “This certainty, when it occurs to me, is so mentally and bodily total that I think I will call it ‘faith.’”

Nocturnal Doubling (4 minutes) is driven by a voice-over that informs us that everything has doubled in size. It is a science fiction brief, though its banal pictures, indifferently shot and largely illustrative of the voice-over, assure us that nothing has changed as a result. Curiously or not, the artist compares himself to God, the first and last measurement, or ruler. Once more, the role of the artist, and the role of the father, are brought together. In Figure Vs. Ground (7 minutes 2004) he takes up a collaboration with fellow video artist Emily Vey Duke as a fight to the finish. Emily supplied him with a clip of her singing on a boat, which he promptly layered up into a dizzying multi-screen display that buried her “figure” beneath his “ground.” Emily dubbed his aggressive material assertions “like being gang raped by video.”

This conversation of fathers and sons is brought to a head in The Imposter (hello goodbye) (9 minutes 2003) a commissioned work for The Colin Campbell Sessions, a program of new movies inspired by the makings of video dad Colin Campbell. Colin began his video posts with a camera borrowed from the football coach in Sackville, and used it to record a gently ironic send up of his small town environs and his big world aspirations. It was a monologue delivered to camera, all in one take, like so much work made in the seventies. This video Sackville, I’m Yours (1972) became a template for Colin’s work over the next three decades, and set up a style sheet for much of the field.

Daniel responds with a performance of his own, also addressed directly to the camera, though as a staunch postmodernist, there is a picture playing beside him, which turns his speaking self into a picture as well. He recounts a dream in which he is asked to read a eulogy for his father. Perhaps this box within a box, this dream within a talk, is a eulogy for Colin? In the movie, Daniel watches a home movie of his father, and regards it as a kind of script. The gestures of his father are a living prison, because he will be forced to repeat them involuntarily. He looks on with the horror of recognition at his father in these movies, “…his body language, which prefigured all the gestures into which I would later grow, thinking they were my own.” Living inside the father, entombed inside the father, is the son. Why else would one need to imagine oneself at a eulogy, if not to cover the wish for the father’s death? But Daniel takes it one step further, and daydreams back to a moment at his father’s bedside. “I had gone to visit him at the hospital, and he had been unconscious, but I thought he might like to hear the sound of my voice, so I spoke to him.” Isn’t he describing video’s primal scene here? The moment the field shifted when his master’s voice reworked the relationship between face and machine, when my monologue became our dialogue? Perhaps Daniel is trying to conjure the unconscious of the medium itself, the unspoken darkness that lies at the heart of the collective project. “I said all the things that I supposed sons were supposed to say to their fathers as final goodbyes, but he couldn’t hear me. I could tell that he couldn’t hear me, so I removed the IV tube from the drip-feed and spoke directly into the tube, hoping his veins would take my words everywhere they needed to go. And I watched my words enter the tube – I could see them, because each word I spoke became a physical artifact upon its entry… and they were all sharp. I watched my words transmogrify into miniature razor blades, syllable-encrusted sewing needles, and miniscule and many-pointed shards of crystal. I watched all of these unhealthy words – these unhealthy physical words – pass from my mouth into my father’s body, and still I couldn’t stop talking.”

He visits his father moments before death, and begins to speak to him, and his words turn into sharp needles that enter his father and kill him. Or perhaps removing the IV tube killed him. Isn’t this a confession? Whenever I speak I am killing him. Or: the only way for me to speak is to kill my father. Every word I pronounce is sharp, that’s how dad feels it, because it’s either him or me. There’s no way for the two of us to talk at the same time, it’s figure versus ground, Arnold versus Daniel, father against son.

In his script for the movie, Daniel has italicized the word physical. The words are physical because they’ve been laid onto videotape. Daniel belongs to the last (?) generation of video artists who made videos, instead of digital files. And it’s clear that the material troubles him, why else imagine the turning wheels of the video cassette skinning him alive? What is the cost of creating an object out of this voice, of putting my voice onto this piece of tape? Again and again, Daniel stages the effects of the medium, dummied up as home movie science fiction excursions and philosophical asides.

And perhaps it’s simply perversity, or the result of watching too many small movies, but I imagine I can hear in this bedside confession echoes of an earlier video by Daniel’s other video dad, Steve Reinke. Like Daniel, Steve is also making a bedside visit, but in place of the father lies his lover Tom. Steve’s relations with his medium are not paternal, but fraternal. And what words does Steve bring to his sleeping lover? “It takes a true professional of love to tell us what we really want. It is my true desire, Tom, to ascertain your true desires. I want to know what you really want. I didn’t bother to ask you because any answers you could give to me would at best be partial. I wanted to capture the truth in its rarest, most primal form… So I’ve been watching you as you sleep. Even though your slumber looks very peaceful I know that inside you are seething. After all, anything of importance happens in our sleep and below our dreams. So I whisper things into your sleeping ear, possible desires transcribed into verbal form, and I watch, I observe you, to see which ones give you an erection.”

Is the sleeper the audience, the artist, the father, the lover? In both instances the receiver of messages is sleeping, and they are being spoken to as if language could be funneled directly into the unconscious. In Daniel’s family story the words are killers, but Steve finds another way for words to function, not as an extension of the home-made jailhouse, of inheritance and command, but as libidinal prompts. He is only hoping for erections. I want to know what you really want.

How to recall again a moment delivered in darkness in Weakend (7 minutes 2003), Daniel’s commissioned contribution to Attack of the Clones, an entire program of shorts that remixed Hollywood’s Oedipal fantasy The 6th Day?

“I love you. Why daddy?”

Daniel Cockburn: Preliminary Notes

He tells me his dreams, sometimes, when I run into him, which is more often than not these days. It seems we are intersecting, ready or not, but I can no more remember his dreams than my own. Though they are so fine I wonder why they aren’t busy grazing screens across the city, though that might ruin it. The act of turning them into movies would only make them less and so they must remain between us as a promise. A promise I can’t help forgetting.

In the pages of NOW Magazine, Cameron Bailey picked Daniel Cockburn as Toronto’s best new video artist and I can only agree. He has a rare literary talent which he serves up with visual élan, smart design sense and a playful philosophical project whose deeply lived roots are leavened throughout with humour. In fact, he’s most serious when he’s having fun. And even though his work appears as audio-visual feuilletons (essayistic briefs, missives from the margins) they possess an uncanny narrative order (though it is a narrativity steeped in the twentieth century, not the nineteenth).

Here in Toronto we are living in an age of commissions. Not Zanuck and Meyer but Charles Street Video and Vtape. Themed appointments, could you imagine making art about? And he can. Each and every one he can. Of course there is a bravura excitement around these home brewed evenings, balanced by an exactly proportional degree of disappointment in the afterglow. Oh, it’s only… Except for Daniel. I don’t know what it is. Perhaps the same thrill speckled rabbits get from choosing a moment to cross the road which most nearly coincides with oncoming traffic. Is it the sense that others are watching, or the more covert run of blood against blood. Whose is bigger? Faster, stronger, made to last? Not that the Canadian art scene is built on winners and losers, au contraire, the reigning philosophy insists that a democracy of attention be granted to anyone who asks. Is it any wonder the work often appears small and grey? But not Daniel. Not with all those pop stars swimming from the mix. And he hasn’t left his Wittgenstein behind either.

He burst into my brain with Metronome (2002), a movie that remixed artist diary and found footage smarts into a meditation on the body’s mathematics. The ratio of walking and heartbeat is explored (he narrates the mystery of stereo, of how it might be possible to hold two thoughts at the same time). A series of movie associations follow, slips which dissolve one star turn into another, faces become books then ideas and back again. Rhythmic infinity (when a groove becomes a loop) is the author’s definition of hell. No matter that there are so many thoughts to think, Cockburn confesses that his experience turns around just a few. What clings to him are repeating moments (already mirrors for his own obsessions), and his joy and despair at this recognition is that memory is founded on repeating, but at the same time the very act admits the threat of over and over.

Superimposed on his heartbeat (which here is a stand-in for the inner monologue) are pictures which arrive from elsewhere, secondary experiences which storm the view screen with an abyss of another kind: the promise of pleasure without consequence. It’s only a movie, right? But this cinephile, who is busy turning himself into an image, tries to weigh the cost of his mediascape. “I wonder what the polyrhythm of all these sounds and movies look like?” muses Cockburn. Once again he finds in the movies a correlative for his own preoccupations: the act of ordering and making meaning. Deploying an elegant clip collage he demonstrates that films are models of sequencing, impossible to imagine without it (what does such an accumulation of capital look like? A face, a kiss, a blown up car, a prison) but at the same time he notes these calculated arrangements lead to despair. A perfect world, in which everything can be known, is perilously close to fascism’s politics equals aesthetics, but without striving to know where is happiness? “All this too is seductive, aesthetic, perfect despair.”

Weakend (2004) was another commission. This time FameFame required that all media derive from Schwartznegger’s sci-fi doppelganger thriller The Sixth Day. Cockburn replays it as an ingenious creation myth, opening with Arnold’s dreamed double encounters, the looped abyss of eyes within eyes, a mosaic of multiplying greetings (“I’m Adam Gibson”), a looped and therefore endless descent, a montage of Arnold’s reaction shots (slowed to approximate understanding with faux triumphal accompaniment), a pulsing screen atop a screen (even the frames are replicating). It closes with a hilarious cut and paste monologue that bears repeating. The words are all derived from the original movie, re-spliced into a different order, sometimes syllable by syllable. How often, after all, does one hear the Governor speak the dreaded words: video artist?

What are you doing to me? I don’t think this is very funny. Who are you? You think you are a media artist because you control me with a piece of software. This is terrible. This is not natural. This is creepy. You know that. I want my life back. You think you are God because you control me. No, I don’t think you are God. I don’t think you are a media artist.

Love me two times Frankenstein and I’ll enjoy you from both ends, making and unmaking you. I prefer your image anyways, the one that’s on my hard drive, cooking all night with new changes. Wait until you see the new you. Though looking forward is something only I can do. You are condemned to looking back.

Is this only the pressure of too many cameras, the relentless surveillance of the supremely visible, the inflated surrogate, multiplied and sprayed across screens around the world? Or is this also “our” momentum, are we already inside a matrix of branded zones (which we announce with the clothes we put on as images, the picture foods we eat, the sitcoms we are busy living)? What happens when a mirror looks at itself? Here at last, in this weakened state, philosopher Schwartznegger is allowed to muse on his too many years spent replicating, offering us warning and prophecy about our own hopes, even as he runs out of his own. He is spoken by the artist, like we are spoken by language, though here in the gridlocked codes of narrative we can see the tensions of power at work as an image is made to appear (“as if” – behind every image is the promise of “as if”) as if it hoped only to escape its own finitude, its limits, sensing that something else might lie outside the frame. (But how to speak of this in a language which forbids it? All experience serves to replicate the code by which we know it, managing repression by demonstrating its usefulness) It’s perceptual SM, this director’s fave genre, one he is making all his own. Longing and limits are the heart of this Cockburn short, made for a program which featured a dozen other studies (though none as finely tuned) similarly served cold from The Sixth Day in a program appropriately entitled Attack of the Clones.

Daniel’s not afraid of being funny, though it’s ideas he finds amusing (which in his hands are only the other side of terror). In Stupid Coalescing Becomers (2004) Cockburn shows us a world where everything is reversed: paper uncuts itself, cigarettes unsmoke, broken light bulbs re-form, pills re-gather and in the final image the artist himself flies out of the frame. A simple jump off his porch becomes, in his capable hands, a sight gag worthy of the old comics. Concise, witty and delivered in a deadpan monologue of mock exasperation (Cockburn speaks with many tongues, he is also an artist concerned with performance), SCB is a protest against the tyranny of forward moving time, a home brewed science fiction short which offers a serial demonstration of a single premise. Of course it is the inevitability of time’s forward motion that is the rub, he offers clock time as prison warder then gleefully rips it apart, sends it hurtling in another direction. Even if it’s only for a moment, in a movie, he offers us this freedom. That it is also a home movie, made for nothing but the time it took to dream it all up is tribute to this artist’s ingenuity. The more often I see his video droppings, the more urgent becomes my necessity. Addictions are born in these oases of image. And I am not alone here. It’s us now, I can speak in the third person. We need these pictures, these thoughts on pictures, these new frames from which to glimpse the impossible.

(Originally published in POV Magazine, 2005)

Smartbomb: an interview with Daniel Cockburn by Mike Hoolboom

MH: Daniel, I’ve decided to email only those I meet in person, and to repeat in these mails conversations we have already had. You told me a dream once, in fact, you have narrated several, all of which I have forgotten. Am hoping you might recount again, so that I can begin the task of remembering my forgetting (which delivers a shameful pleasure, one day this will not be the best kind).

DC: I’m not sure if this is the dream you’re thinking of, but it’s the one I’m thinking of. It took the familiar shape of a horror-movie narrative; there was something terribly wrong with the world and I was the only one who knew about it. I found a mini-DV videotape in an alley and as I picked it up, the reels started to revolve, like in Starman (the TV show, I never saw the movie). Jeff Bridges could hold an audiocassette to his ear, telekinetically cause the reels to turn, and hear the contents of the tape. Now the reels were turning of their own volition, and I could not see or hear what was on the tape… but as I held it between my thumb and forefinger, watching the reels turn, I saw that the tape was slowly peeling a strip of skin off my fingers and winding it around the reels. I tried to drop the tape, but I couldn’t, because my skin was inside it. I worried this process would continue until I gradually lost all of my skin to the inside of this mini-DV tape… but some more tugging managed to snap the skin and I dropped the tape to the ground.

Later I was with a group of people (we may have been at a restaurant, though I think that first I was in a hospital emergency room inside a mall), seated near a woman about my age whom I had never met before… but, in familiar horror-movie-narrative fashion, I Knew That She Knew. So I leaned over to her and said, “I think there are some terrible things happening, and that you and I are the only people who can see them.”

She responded, wide-eyed, “Yes! Exactly! For instance…” and here she opened her mouth and pointed at a dark gap where two front teeth should have been. “Look, I accidentally knocked two teeth out with my toothbrush while I was brushing my teeth this morning.”

This troubled me greatly; I knew that if teeth were so easily falling out of heads, something was amiss. She continued, “But that’s not the horrible thing. The horrible thing is that…” (now she points at two white teeth farther back in her mouth) “THESE are the teeth I knocked out.” Pointing back at the dark toothless gap: “THESE teeth are still here. It’s just Not Showing Up Correctly.” This, to me, was perhaps the most upsetting thing yet.

I can’t remember where the dream went from there. But here’s another one that I had a while ago:

I dreamed the existence of a 1970s TV cop show. It was about an undercover policewoman. The whole series took place with her on an ongoing undercover assignment at a summer camp for incontinent elderly people. The heroine’s name was Slapper Coleco.

My dream was only about four seconds long. It was a still image, a promotional image for the TV show. The image looked like this: a woman standing in a sunlit forest, holding a gun. Beside her, text (the name of the show): SLAPPER COLECO, UNDERCOVER SUMMER RUBBER PANTS CAMP DETECTIVE.

MH: Do your dreams come with laugh tracks and audience applause? Mine often have closing credits (which threaten, at least occasionally, never to end, some repression of pictures seems at work, entire dreams consist of nothing but words, which appear as images of language). I am sorely tempted to offer a backseat analysis of your dreams, as they seem ripe with pictures of a threatened body in the shadow of videotape, specifically digital video. Video and the body have been a duet since the beginning, when black and white portapacks were too heavy to carry around easily, and artist’s studio practice refocussed art matters onto the body, the videotaped body. You often appear in your own work, a fact I thought initially unlikely, perhaps because you appear to lack some necessary fundament of narcissism, but of course I don’t know you so well. As your work slowly gains a public life, how have you begun to re-imagine your body, which has been pried loose from its physical moorings, and which now exists (in always younger, presumably “better” versions) independently of you, as an image?

DC: I can’t think of any dream I had that included laugh tracks or audience applause, or any indication of a studio audience. That’s so TV; my dreams are cinema!

To your question of body:

I have a group of media-making friends who meet irregularly, and we sometimes set each other challenges (“obstructions” in the Jorgen Leth/Lars von Trier model). A few years ago, we were speculating as to how each of us would deal with the parameters of a certain project, and one of the group said to me, “Well, we know your movie won’t have anything to do with sex!” This sentiment was laughingly echoed by everybody, including me.

That is to say: I have made it a habit of ignoring the body’s presence in my life and in my motion pictures. To my mind, my body has been a mere conveyance for the life of my mind. You may disagree, since as a viewer you only see the result, not the intent; but my position as maker means that I can only see the intent, never the result. (Once enough time has passed since the making of a video, the trueness of that statement fades to grey; I can look at Rocket Man and at the very least think it interesting that I am/was that fellow with blond tips and a beard.)

You mention that “Video and the body have been a duet since the beginning”, but I wasn’t around in any meaningful consumptive/productive sense for that beginning. I’ve come to video (via super 8, 16mm and linear video editing) more or less as a “user” in the MicrosoftTM sense. The tools I know are the ones software companies deem worthy to provide, based on some sort of uberdemographic knowledge they have of me whether or not I’ve ever filled out any survey (for the record, I’m pretty sure I haven’t).

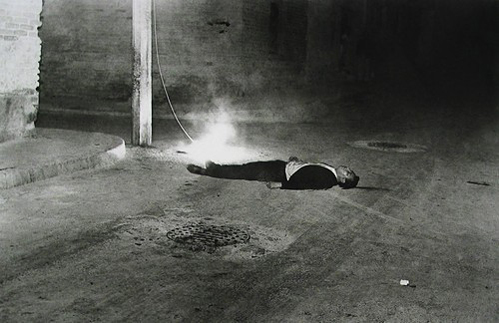

Digital video scares the crap out of me, more so than film by a long shot. The Other Shoe was a not-very-veiled plea for the virtues of film over those of digitalia; Metronome alludes to the physical experience of life in a digital age; the/my body is presented as a thing stuck living out the mental loops of its controlling brain. Governor Schwarzenegger is condemned to the seven circles of digital hell in WEAKEND, and I think Continuity is the most explicit statement of digiphobia I’ve yet made. Tasman Richardson asked me after its first screening whether the scene in which I burned my hand with a cigarette was real; in answer, I showed him the scar, reaping and revelling in the perceived benefits of full macho I-sacrifice-myself-for-my-art-dom. He was glad that it was so, and made the pertinent point that up until that moment there had been ambiguity about whether I was “merely” portraying a character or existing as myself in the time of the video. But at that self-immolative moment, the two merged into one; scripted or not, That Guy On Screen was really burning himself, the pain was real, and fiction blew out the window.

Four Addenda:

1. But I feel sorry for that guy that who was me, though any apology is futile since it was my fault that I made him do that.

2. Since Tasman had to ask whether the burning was real, the moment must not have been fully realized.

3. Jubal Brown fully believed that I had burned myself but asked whether the preceding nerve-steeling swig of gin was actually water; in fact, it was straight gin, but I suppressed my wincing reaction so I wouldn’t seem like a wimp. The effect of my steely self-control apparently made me seem like a wimp for drinking “fake” liquor.

4. A few days after shooting that scene, I realized how stupid it had been, since the mark on my hand was just getting worse and worse and maybe I’ll actually have a scar… Which would make me more like the scripted character than I would care to be.

Similarly (so similar, in fact, that it’s probably redundant): in (repeatedly) shooting the final shot of Stupid Coalescing Becomers. in which I unfall upwards out of frame, I hurt my knees and they ached for days afterward. I never remember this fact when I watch or think about this video now. That guy onscreen has a lot to do with me, but he doesn’t have much to do with right-now-me at all.

Certainly I harbour a fear of film, insofar as I harbour a fear of anything which purports to represent the real but whose representation is not one hundred percent infallible/unquestionable (i.e. everything). But digital video seems to offer the most seemingly perfect representation while also translating it through the longest and most cryptic series of incomprehensible procedures. I remember reading a Film Comment article about the impending release of Fight Club which said, in effect, “with the arrival of this movie, film is no longer an index of physical reality.” An exciting turning point, to be sure, and also one which I keep wanting to persuade myself we haven’t passed. Whatever you say about it, a film frame is an object which bears the physical imprint of reality. A videotape is an object which bears an analogically encoded imprint of reality. This is still somehow acceptable to me… but once you get into digital video, and the tape-object is merely a carrier for various file formats, for language that humans will never be able to comprehend (though they may have invented it), it seems somehow heretical that we should think that the image and sound which spew out the other end of this tape/computer actually embody a connection to reality. Bearing a resemblance and embodying a connection are two different things.

I make things which, without the benefit of decoding devices which I can never hope to comprehend, would be unintelligible to anyone, including myself… things which, without the benefit of said devices, would cease to exist, even though their rectangular plastic-and-code containers might live for ages.

Writing all this I am extremely dissatisfied with my expression of it; my thoughts have been translated from various states and media into this final digital output via text via fingers. And of course to say that it is untruthful because the number of links in this chain surpass some reverse quota would be silly. Nevertheless I am frustrated at the chain of translations which makes the seeming truth seem to recede.

So here’s something else.

You asked earlier: “How have you begun to reimagine your body, which has been pried loose from its physical moorings, and which now exists (in always younger, presumably better versions) independently of you, as an image?” I recently visited the dentist and was told one of my wisdom teeth is rotated ninety degrees sideways assuming it’s Showing Up Correctly. It should be taken out but it’s sitting right on top of a nerve, so the operation could possibly result in losing some sensation in my lower mouth. And I wondered what it would be like if I were to have my mouth go slack/disfigured, de-normalizing my face and voice. Would I still continue to use my face and voice in my videos?

I realized that it would feel difficult to do so without some acknowledgement of that face’s/voice’s abnormality. And this made me realize that I therefore must currently be using my physical audiovisual persona as some “normal” or “normative” manifestation; a body and voice via which I can express all of my concerns which don’t really have specifically to do with body and voice. Were my actual body to undergo some change, I would feel uncomfortable about using it as an idealized vehicle… which is ridiculous since it implies that I consider my current (youthful white guy) body-state not only normative but idealized. I don’t think I have re-imagined my body at all, in an actual sense, but my encounter with my inability to re-imagine it has at least exposed some of my own hypocrisy to itself.

MH: Your attentions lie with models of subjectivity and cognition, using yourself as model. What stops this from being only narcissism? There are terrifying cruelties enacted around us daily, the AIDS pandemic continues to ravage large parts of the world, genocide continues in Indonesia, what does it mean to make video art in the midst of these punishing realities. Is it only a more rarefied form of escapism?

DC: I don’t think art has to change the world, only the people in it. And escape can be a form of change, provided the escapees return to the world after their stint abroad or inside, and provided said stint is a fruitful one. I think video art that speaks not one explicit word to the problems of the world is as defensible as an equally “escapist” conversation. Political discourse is necessary but if every verbal exchange were graded against a quota of explicitly political content, there would be a sore limitation on the number of possible dreams—to say nothing of the number of implicitly political dreams.

How it’s positioned is the greater difficulty/problem. My videos certainly have a narcissistic core—and worse!, it’s the narcissism of a well-off, white North American male—but your phrase “using [my]self as model” is key. If I examine myself closely and rigorously and honestly enough, it will be useful not only to me for my own reasons but to others for their own reasons. I’ll be satisfied if people glean from my videos not “this is what Daniel Cockburn is like” but “this is what a particular well-off white North American male in the early 21st century is (or was) like.” I don’t mean that I am submitting myself as a representative sample, a normative or ideal or “model” citizen for time-capsule posterity (though this is a problematic subconscious tendency of my work which I mentioned earlier); I mean that I am offering myself in my work as a self-expressing locus of various external tendencies at this point in time and space. My environment in large part has made me what I am, and from my work the audience may extrapolate various thoughts about that environment.

All of this, however, assumes people actually see the work. Current presentation modes ensure that my videos are seen only by a very specific slice of the population. Work away at work which will be seen by precious few? I can do nothing else, and few is infinitely better than none… To somehow preach the gospel of alternative dream-styles to the uninitiated and uninterested majority would perhaps, if I really believe in all of the above, be less of a sell-out. And anyway I have not yet given up the ghost of narrative feature filmmaking.

MH: Doesn’t your work rely on an audience already hipped to art recodings, savvy in the ways of stolen pictures, drunk and drunk again on deconstructive cocktails? Isn’t this insular insider art, and isn’t this the forever instance of Canadian art scenes? Hosting government-appointed screenings for the faithful, an audience of like-minded makers, where consensus is everywhere and who can remember what you saw in the blizzard of the too many shows on offer. Politically at least this seems (the situation I mean, not your work in particular) to be a large step backwards.

DC: I would like to think that my work actually doesn’t require that the audience be hip, savvy, and/or drunk on art and deconstruction. Or, to put it another way, I think anyone even slightly schooled in our current mass media should already be sufficiently hip, savvy, and drunk. Personal video diaries, amateur (read: non-Hollywood) narrative filmmaking, re-jigging of iconic images and sounds… anybody with internet access should be familiar with these and other previously-non-mainstream modes of making and receiving. And even if you don’t have a broadband connection, as long as you’ve been watching some movies or television in the last decade you’re fully attuned to postmodern intertextuality (the contemporary version of which is certainly toothless, far from the critical weapon that I understand it was originally meant to be, but nevertheless it’s a popularized form). The consuming majority accepts intertextuality in Michael Bay’s The Island, video diaries on Jackass, and cultural appropriation on fenslerfilm.com, so there’s no reason they shouldn’t accept like-minded fringe media.

Yet we know they don’t. Audiences for fringe work are composed almost exclusively of fringe-makers and people otherwise closely affiliated with the arts sector—and the latter set, I suspect, rarely exceeds the bounds of the former. This is at first encouraging (you get more applause from friends than you do from strangers) but eventually demoralizing. Where are the people who don’t give a rat’s ass about “art,” who just want to see something good? They don’t come, and frankly I don’t expect them to.

At this point, a greater obstacle than form or content might be modes of presentation. People will accept most anything if it’s in a music video or on some crazy website; when they pay money to sit down and look at a screen, they expect to see movies. The parameters of what constitutes a “movie” are broadening, but they’re not yet wide open. So artists are left showing videos to each other in rec rooms that we rent with arts-council money.

This problem could be eliminated by revoking the funding, in the same way that a lot of bad art could be eliminated by dispensing with production grants. But both those tactics solve only the superficial problems. Ceasing production grants won’t cause more good art (though it might up the good:bad ratio). Nor will ceasing exhibition funding cause the general public to seek out fringe work. We’re in a holding pattern right now; nothing wrong with that but the fuel doesn’t last forever. What at first seems encouragement becomes lack of criticality; the community is so small and interconnected I think people are terrified to express honest opinions of bad work—how then are artists supposed to get better?

Is the solution for video art and fringe film to enter the market (not the art or educational market but the popular market)? Sure, the popular market will not necessarily support the most worthy work; and even in our current system, artists struggle to achieve a standardized level of compensation for their work. Every impulse I have with regards to this situation feels more capitalist than I thought I was. I’m not convinced that that is always awful. I’m not convinced, you may say, of much.

[In summary (working backwards): my art is made for and shown in an insular insider art scene, but it is not insular insider art.]

MH: Why can’t artists produce work that con-forms to more generally accepted media portals: the feature film or 50 minute television documentary? Why all this work on the signifier, on skewing the form, changing the way we show pictures, or listen to sounds? Does it really make new experiences possible? I used to think so, but that would mean that fringe devotees would be examplars of virtue, their happiness organs bigged up on all those hours of difficult light. But fringe media is hardly a guarantor of a better life, so why bother?

DC: Refusing to make your work accessible is not a sin, though doing so for no reason other than elitism or spite is plain silly, and I think that refusing in your creative process to acknowledge and incorporate the existence of your audience is at least a mortal error. Certain types of experience cannot be transmitted in the feature-film or 50-minute-TV-doc format, just as certain types of experience which those formats transmit so well are anathema to short-film or non-narrative work. Not all art has to be free, unfettered newness, but the spectrum of available art absolutely has to be an arena of possibility, otherwise what’s the point? Form can be founded on a moral foundation, but that doesn’t mean form will necessarily generate morality in the receiver. This is how communication works, and we have to take what we can get (and give what we hope can be gotten).

My experiences of fringe transcendence are pleasures like no other I know. Why shouldn’t new pleasure be a worthwhile offering? Our happiness organs do get bigged up on light-bending… it’s just on a very narrow spectrum of happiness. This is a problem if you mistake light-happiness for world-happiness, which is certainly the case for some of us who get a certain horizon-broadening from fringe work and then seek out a repeat of that same, lovely, immensifying feeling at screening after screening, rather than go out looking for it in a world whose horizons have supposedly just been broadened. Every pleasure carries within it the seeds of addiction.

However deluded or realistic our motives, we who are familiar with experimental form and work are prepared to wade through the shit for the good stuff. The general public isn’t, nor should they be. If a chef friend took me to a tapas restaurant which she highly recommended, and we ordered twenty dishes, two of which were mind-blowingly succulent, fourteen of which were passable, and four of which were repugnant, would I not be justified in refusing to return (especially if I knew that the menu was entirely changed twice daily)? The festival-programming or curated-screening format works for those of us who are already in the thick of things, but hoping that people open up to new ideas on the basis of an assorted appetizer platter is at best naive (and thinking that the appetizer platter is the only kind of meal there is dangerous self-limitation at the individual and at the community level).

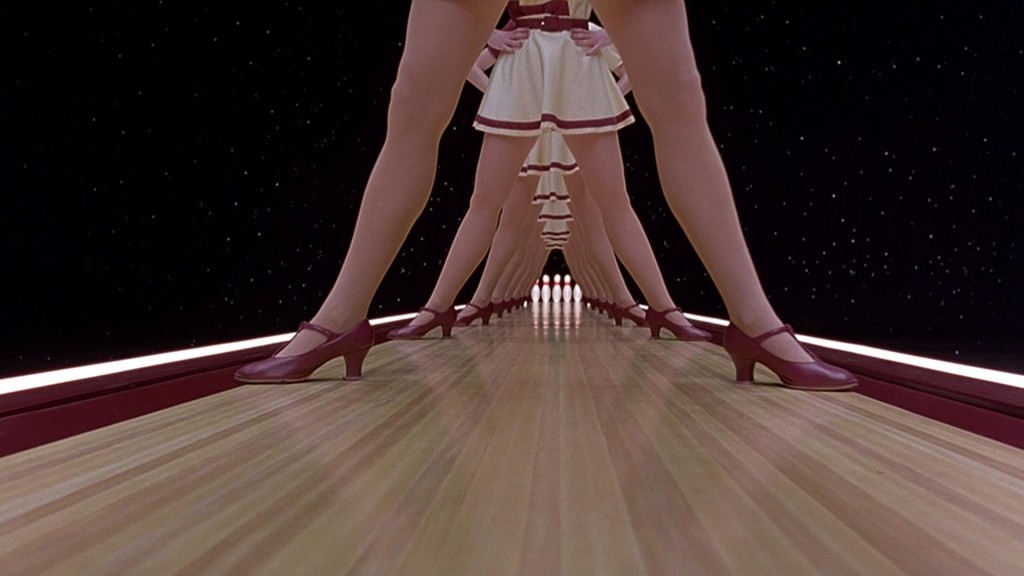

A previously-typed aside that no longer feels integrated but which I cannot quite bring myself to delete: [I mean, the MuchMusic Viewer’s Choice Awards just named 50 Cent as “the year’s best video artist.” “Video art” obviously has a very different meaning for most people than it does for us. Not to say that we’re right and they’re wrong, but the phrase’s current majority-definition obscures the existence of the type of work we’re talking about. (The only other “video art” reference in the public canon that I can think of is David Thewlis’s portrayal of “Knox Herrington, the video artist” in the Coen Brothers’ The Big Lebowski (itself only half public, but an underground cult thing of the above-mentioned order which I would love to see some experimental work attain (and anyway you haven’t seen that movie, or at least you hadn’t when Mike Bullard asked you about it, so maybe you’re the problem here) which more or less reaffirms the general cliché stereotype of video art=high pretension).]

I feel my answers are growing increasingly committed to absolute diplomacy; my eyes are sliding farther apart from one another and soon I’ll have one over each ear, resolutely seeing both sides of everything. Which will be great except that I won’t be able to see where I came from or where I’m heading.

MH: What kinds of experience can’t be relayed through mainstream portals? And what is it in your biography (real or simulated), or your work, which can’t be dished up in familiar audiovisual formattings?

DC: The image-propagation world is growing, it’s increasingly the world in which we communicate with one another and experience imagination. The more often pictures replace the world we live in, the more we accept dominant forms as a fundamental syntax. As advertising, feature films, TV, news, video games, and the world wide web converge, we need to remember that, for example, while moving images may not be the ideal way to convey foreign policy news, moving images which borrow specifically from advertising or video game forms can only limit such conveyance even further.

We can use images to explore alternate ways of transmitting and receiving—oh, but what ways are they? That was your question, wasn’t it? I’ll answer by first seemingly avoiding it for a little while longer.

Images are becoming less and less precious, and their connection to our world increasingly superficial and misleading (and this goes back to my greater fear of DV than of film). I think this leads us to regard our own lives as less precious.

Tarkovsky said, “I think that what a person normally goes to the cinema for is time,” and he wasn’t just talking about arthouse audiences. All films offer an experience of time segments which have been elongated or compressed into a singular experience (otherwise why not just have a relationship with time on the street outside the ticket booth?). The current trend is one of speed and diversion; these have their uses but at this point the fringe is where I have to go to find the alternative.

There is one place you can find plenty of static shots, and that is TV advertising. We have learned that slowness can be appreciated but only briefly; slownesses thus follow one another with great rapidity, as refreshing as ice cubes shooting out of a volcano.

Gus van Sant’s recent work (and he, I suppose, is on the fringe of the mainstream) is exemplary of current success in this regard; watching Gerry or Elephant, one becomes reacquainted with the pleasures of long-form attentiveness summoned forth by a slow-moving object, and I’d like to think that I carry the taste for this pleasure outside with me afterwards. I’m convinced that we’d be better off were the world at large (me included) more attuned to such things; longer attention span means greater capability of complex thought, means greater empowerment (and awareness on which to found your choice as to what to do with your power). I’ve made stabs at this kind of pleasure with The Other Shoe and The Impostor (hello goodbye), placing single-takes in a multi-frame context which I hope will point out their purity while distracting from and, sadly, destroying it. Not that I am fixated on slowness and the long-take aesthetic, or that I think we need to become a society of humanoid glaciers; Metronome and Stupid Coalescing Becomers. both seek to foreground time-awareness via other means (rhythm and reversal).

You also mention my “work on the signifier, on skewing the form, changing the way we show pictures, or listen to sound.” I hope that in my appropriation I manage to express my relation to the current way in which I receive pictures and sounds, thus providing a model for my own thought which can form a model for the viewer’s. I can’t imagine that this would have as much chance of success on—for example—television, where in the first place image-appropriation is illegal, and secondly it would be subsumed into the background noise, becoming indistinguishable from its original sources. My appropriation videos are preplanned and highly controlled channel-surfing, as indeed is any montage; in this sense their pleasure is the same as the pleasure of narrative film. The other pleasure, though, is that of being taken on a guided surf through the media we’ve already consumed; this will hopefully spread the desire to reorder the contents of one’s own brain to arrive at one’s own conclusions.

If I still haven’t answered some of your questions, prod further, prodfessor.

MH: I’ve always wanted to make a movie in paralyzing slow motion so that afterwards, after watching someone get off a chair for half an hour, or drink a glass of milk for ten minutes, one could leave the theatre and everything would appear strangely sped up. But of course these effects don’t last, these perceptual oases are temporary effects, the crack cocaine of the picture world, soon requiring another hit to keep the senses from re-orienting. How to deal with our present deluge of too many pictures? Why bother producing when there’s already too much, knowing that whatever you do will so very quickly become subsumed in the evening news, the morning headline, the restless chatter of celebrity?

DC: If by “these effects don’t last” you mean they don’t last forever, then I agree. But I also agree that they’re temporary, and anything that’s temporary does last, just not infinitely. And just because something isn’t infinite doesn’t mean it’s not worthwhile (the pyramids have lasted quite a while, and they’re likely to last a long while longer, but they are definitely not going to last).

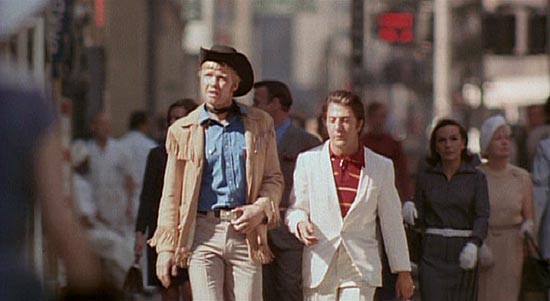

I was about thirteen when I saw Midnight Cowboy, and today, the one thing which stands out for me is not any of its famous lines or images, but a small speck of time in which Jon Voight defends his cowboy attire to Dustin Hoffman. “Why do you have to make fun of my clothes?” he says, “I like these clothes and I like the way I look in them. I feel good about myself when I wear them.” I was a teenager with an intellectual-superiority complex living in a small town, and this moment forced me ever so subtly, but consciously, to reconsider my sense of being better than a lot of people around me on the sole basis of personal taste. And that moment of consciousness is one that I have returned to (or have had returned to me) over the years up to and including even now, whenever associations conspire to re-uncover it.

Things get subsumed but, as I mentioned, they leave residue, and that layer of intra-cranial grime can certainly last, and even occasionally contain seeds.

MH: Daniel, as usual you put it so well. Grime that contains seeds, or as Jonas Mekas once asked, “Where are we, the underground?” It’s too much for anyone to bear, to carry the burden of representation for all pictures, all the time. Pictures, we imagine them (don’t we?) as something evanescent, made of light, as light as air, and yet sometimes they’re heavier than lead. And just as opaque. I would like to shift focus and speak about a couple of your movies then. Can you talk about Stupid Coalescing Becomers.? It is a backwards time fantasy, a home movie redressed as science fiction. Could you briefly describe the movie and tell me how it came about?

DC: Stupid Coalescing Becomers. is a three-minute video with continuous voiceover. The images are fairly standard backwards footage: a cigarette burns from ash to fullness, a hammer-wielding hand smashes glass shards into light bulbs, etc. The voice-over is a moral diatribe against the “stupid coalescing becomers” who think they can avoid acknowledging the cause-and-effect workings of the world by temporarily (but ultimately futilely, in the narrator’s opinion) reversing time for themselves. The narrator’s identity is ambiguous; even at the end, when a human body falls reversedly up and out of the frame, it’s uncertain (unless you know me) as to whether this body is the narrator’s or whether it belongs to one of the Becomers.

A few years ago, when Jeremy Rigsby was still the Artistic Director of the Media City festival (Windsor, Ontario), we met up in Toronto at the opening night of the Images Festival. I asked him at one point whether he had seen a super 8 film called Smartbomb (the filmmaker’s name did and does escape me, though it might have been Marnie Parrell), and he said that there were too many experimental films called Smartbomb, and that someone should make a film called the opposite of Smartbomb. “Stupid… Flowers?” was the tentative first title suggestion, but we gradually came to the conclusion that the opposite of an exploder would be a coalescing becomer. We both agreed that someone should make a film or video called Stupid Coalescing Becomers, and I thought it would be lovely and hilarious if I could present him with a VHS tape containing said movie before he went home at festival’s end. So I made the movie that weekend (adding the period to the end of the title for greater assertive effect, the three-word phrase having taken on a definite insulting third-person tendency) and gave him the VHS tape on closing night when I said goodbye. He got a good laugh out of it (my handing him the tape, that is), which was the sum of my original intent, to please someone and myself not with the movie itself, but simply with the fact of its existence.

Then of course I hemmed and hawed about it for a year and a half, vaguely thinking about re-editing, re-recording some voiceover… I can’t remember if I made any cosmetic changes before mastering it and taking it off my hard drive, but I probably didn’t.

The backwards-ness seemed a natural concept with that title as the starting point; I think I was leery of the fact that I’d already seen several experimental videos that year alone which took backwards footage as their main selling point (Saki Satomi’s M Station Backward; Eno-Liis Semper’s FF/REV; I hadn’t (and haven’t) seen Jeroen Offerman’s Stairway at St. Paul’s but I’d heard plenty about it, where he learned Stairway to Heaven backwards and sang it while people strolled past). Most of the ones I’d seen were good, but taken together it seemed like artists were in need of a new hook, and here I was making another backwards movie. So I think the voiceover grew out of a tendency to chastise them and myself for using a device which, let’s face it, has been around long before that guy backwards-sang What a Wonderful World on America’s Funniest People back in the 1980s. And, it occurs to me, my above description of the Becomers as beings who “think they can avoid acknowledging the cause-and-effect workings of the world by temporarily (but ultimately futilely, in the narrator’s opinion) reversing time for themselves” fits with your previous and implied definition of video artists/audiences as willful self-oblivionizers.

MH: In the future not only an iPod, but iDrives in iCars. iMovies already exist (you claim you make them yourself), and iJournalism we already see too much of. Now let’s see. Your WEAKEND project turned Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger into a reflexive digital philosopher. Can you write me about how this project began, how restrictions (prohibitions, taboos) can provide freedom, and why the Governor is a particular apt figure (or is he?) for the new role into which you’ve cast him.

DC: How it began is the easiest question. Media art collective famefame curated a program called “Attack of the Clones” for the Tranz Tech Media Art Biennial 2003 here in Toronto. The call for submissions requested videos whose sole audio/video source was The 6th Day, a Roger Spottiswoode-directed, Hollywood sci-fi film whose star is Arnold Schwarzenegger, and whose subject is cloning. The idea was of course that all videos in the program would have the same DNA, so to speak, all clones of the original 35mm opus.

I want to answer the question of how restrictions (or rather let’s call them parameters) can provide freedom. It makes me think of the Lars von Trier/Jorgen Leth film The Five Obstructions, in which von Trier gives Leth a series of assignments consisting of parameters to which Leth must adhere in remaking his own short film The Perfect Human. Leth breaks the rules in the second assignment and von Trier punishes him by making the next assignment devoid of parameters: absolute freedom. Leth retreats to his hotel room, where he laments, “This is the worst one yet.”

We always have restrictions, more and less visible, when we make anything. You can’t make a video that lasts longer than the life of the universe; you can’t have a projection screen bigger than Ontario; you can’t render explicit something you’re too frightened to admit. It’s simply a useful exercise to start out with a more-defined-than-usual parameter set. In the case of WEAKEND, my remix of The 6th Day, I was very excited about the project—until I finally watched the film and was so underwhelmed by its content and images that I felt sullenly noncommittal. The best I could come up with was a series of digital gimmicks to perpetrate upon Arnold… which would be fun but hardly seemed enough to hang a video on. So I felt I needed to give them some context and use (and also expiate my moral twinges at playing with Arnold so cruelly, doing to Arnold what I usually do to myself) by giving Arnold the epilogue in which he criticizes the proceedings.

By splicing together words, or parts of words, I have him speak a new text: “You think you are a media artist because you control me with a piece of software? This is terrible. This is not natural,” and so on.

You know, I saw footage of Reagan’s funeral, or at least memorial service, and Schwarzenegger was there, and he made the sign of the cross, but I could swear he made it backwards: up-down-right-left instead of up-down-left-right. Mirror images of religious iconography do not often portend well, at least in my experience (of watching horror movies and other less interesting movies in which characters played by people like Arnold Schwarzenegger fight demons). It also occurs to me that perhaps the explanation is simple: the image itself was flipped mirrorwise for some purely pragmatic reason known only to the networks. Which itself is cause for alarm in ways I hope I’ve already expressed at length in this interview.

In answering your question I had to remember how to spell “Schwarzenegger,” so I went to the IMDB, and ended up reading a user review of The 6th Day, which, like so many of the reviews on that site and most of the rest of the internet, left me thinking “what’s the point?” about most of the things we’ve been discussing. I reproduce the closing paragraph here.

“What impresses me most of all about movies like The 6th Day is how the writers deny the urge to allow the special effects and action to take the place of the characters. In the year 2000, we received big waves in The Perfect Storm, big explosions in U-571, computer animated sequences in X-Men, and all sorts of special martial arts stunts in Charlie’s Angels and Legend of Drunken Master. But what those movies were missing is depth and insight of the real world, and the movies that did contain heart, like The Perfect Storm, were contrived and shameless. With The 6th Day we have a movie that contains all the excitement and special effects, but within a story that is character-based and relevant to our times. This is one of the top ten movies released in the year 2000.”

MH: We were both invited a couple of years ago to produce a short video as a reaction shot to the life and work of the late Canadian video artist Colin Campbell. One of the curios of this commission was that Colin had long been surrounded by uber talents from the art world, but Lisa Steele, the woman who commissioned the project through Vtape, a distribution organization which was co-founded by Colin and Lisa amongst others, approached only artists who didn’t know Colin well. She always has an eye for outreach, and it was from this missionary position that the work advanced. I felt ambivalent about the results, particularly because Colin was dead, there was no way he could defend or represent himself (why do I imagine defense and representation are the same?). To add this insult to his untimely death: a badly made piece of video art struck in his name. I was confused by your movie when I first saw it, it was so archly ironic, and spoke incessantly about death but in an almost cartoon fashion, without any feeling at all, though there is much mention of tears. When I saw it I thought it was an image of an image of grieving. But now that I’ve soaked in it a while and screened it more often it’s becoming clearer. I’ve crossed some threshold of your intention, and am happier for it. I’m wondering if you can talk about its making and your thoughts about Colin.

DC: I hadn’t realized that The Colin Campbell Sessions were such an outreach project. (Nor am I sure which video you’re referring to as “a bad piece of video art struck in his name;” all of them, perhaps? Including your own?) Are you sure none of the artists involved knew Colin? I was under the impression that at least you had known him; you’ve certainly done well to foster this impression in eyes mine and public with your own Colin video and with much allusive talk and activity since. But maybe you aren’t counting yourself.

Anyhow, it’s funny if you are right about that, because my entire video is a response to my (mis?-)apprehension that everyone else in the program had been intimately familiar with and influenced by the man and his work, whereas I had virtually no knowledge of either. I thought it had been assumed that I, like everyone else, was a Colin-friend and-ophile, and I felt I’d be a fraud if I accepted and took the money and got the glory… but then I figured that to come clean about this in the video would be even braver than declining the invitation altogether.

So of course my “coming clean” is a little cryptic, and I’ve substituted a fictional dream about my fictionally dead father for my real misgivings about Colin. This is partly because saying exactly and artlessly what you mean is generally… well, artless, and partly because (I must come clean here!) I was afraid of saying what I meant.

Even as artifice-woven as it is, at its premiere I was very afraid that in so exposing my own ignorance and fraudulence amidst an audience of Colin’s friends, advocates, and aficionados I was about to pour salt in their wounds and incur their wrath (“who is this nobody who made us think he was somebody and then rubbed it in our face after we’d already given him recognition?”).

But the reception was warm, so either they didn’t get it—which would likely be a combination of their inattentiveness and my intent-obscuring crypticism—or I had managed to extrapolate from my feelings about my non-feelings about Colin a less specific and more resonant experience. I don’t know how much I can agree with you that it’s “unemotional.” Certainly it’s inexpressive facially and vocally, as I usually am in my videos (I try to know my limitations)-and you also call it “cartoonish,” which reminds me that most of my videos (including this one) evoke audience laughter, which I get such a quick taste for that I forget the surprise and conflict I felt on first hearing it.

Alex Glenfield’s music is the emotional anchor of the movie (Tarkovsky said that electronic music at its ideal could “be like someone breathing”). I think anybody who finds The Impostor entirely arch or comical is focusing so much on the text that the music is not allowed to get under the skin. Alex composed and recorded it a couple of years before I was invited to make the video, and he first played me the CD while I was formulating the concept. I thought it would be appropriate for The Impostor, with its waxing/waning, loop-like structure, and when he told me the title and the sonic ingredients, I knew it was doubly perfect. He’d been thinking, he told me, about Morse code and its use as a means for soldiers to send messages to their allies during wartime. Would anyone ever have formulated a message for his enemy?, he wondered, a proposal that sounds melancholy and humane to my ears, and so he made this piece of music which is the phrase “FOR MY ENEMY” in Morse code, repeated and superposed at various pitches. (There is also, he later told me, a second Morse code phrase in the piece, but no one has yet been able to decipher it, and he refuses to tell.)

It seemed fitting since the character in the video has an adverse relationship to his late father (who is also himself)-an antagonism born of disassociation, of one party’s ignorance and the other’s absence. If the video is resonant, it’s because of his attempt to throw a connective rope over this chasm, even as a third aspect of himself scissors the rope into little bits. And this is a pretty good expression of the way I feel, or don’t, about Colin.

By this I mean Colin is an influence at second remove; I understand his work by having heard people talk about it, by having seen work made in its shadow. So my work is the shadow of a shadow, a second-generation copy at best. For me, in the context of video art, Colin is like—for instance—Orson Welles (and I mean the Welles of Chimes at Midnight and It’s All True!, not the Welles who made Kane and Touch of Evil and the other few that I actually have seen), or like all the Godard or Snow that I know enough about to pretend I’ve seen if the conversation doesn’t get too specific. And if we stand on the shoulders of those who come before us, then I’m standing on someone who’s standing on Colin’s shoulders, and I’ve gotten to this height to no credit of my own (no self-aggrandizing, this; by “height” I only mean the point at which everybody now is at, as a result of everything made up until now).

And I want to build on what I’m standing on, not just fritter away my vantage point from atop the dead, yet it feels that in order to do so I have to wrest attention away from them, towards myself (because attention is a finite resource). I don’t know if they are my enemy-I doubt it, in fact, for they have given me so much—but quite often I feel that I am theirs (or maybe “rival” is a more accurate, less stinging though also less evocative term than “enemy”).

At any rate I feel a need to justify or defend myself… even if only to myself, to make me happy. And as you imply, defence equals representation, so I can at least represent myself. That’s The Impostor, and Colin, and me.

I am of course wondering what was the threshold of my intention that you crossed, and where you found yourself.

MH: I met Colin only twice, and he lit me up like a fuse before disappearing again into that swarm of adoring and remarkable friends that I am slowly getting to know as I continue this project of portraiture, chasing his echoes. When we glanced off one another he seemed a formidable figure from the past of a medium I had embraced only recently. He was able to make magic when video meant black and white and bad sound and no editing so his practice provides, just as you suggest, the necessary sediment, the firmament, on which we are having this discussion.

You make a gesture towards this ur-time with your tape, which is made in a single shot (no edits), as a performance for camera, a first person funeral oration for your dead father. You deliver this monologue in a manner Colin would have relished, brimful with irony. But irony is very low on my pleasure register, the joys of camp and kitsch have proven elusive, I am either not large or not small enough to appreciate them. The music you mention I must confess has breezed past four or five times now with hardly a notice, not that music requires notice to be effective, but I am fixated, as usual, on your performing presence. In this movie you play a self-conscious fairy tailer who narrates a dreamed deathbed visitation with dear old dad, and then hyperbolizes a moment of response at the funeral. Your inheritance, you insist, relies on the amount of tears you can wring from your audience. This is all recounted in such a studied fashion that the first few times I watched I felt nothing but far away. Is this the theatre that old Brecht had in mind? The alienation effect, the ability to study the scene in front of you without the mess of identification. The truth is, I still don’t find it moving, but of course as George Lucas once said, hitting a cat on the head with a hammer is emotionally stirring for audiences, and anyone can do that. I once felt Colin’s passing deserved more but no longer. I don’t believe that your movie needs to reach past itself to provide emotional transport for strangers. Nor to provide a stage for our emotions, or demonstrate how emotions are made (oh look, they’re crying, no wonder I feel sad). Instead, your movie offers the more vicarious pleasures of the meta-verse, not emotions, but emotions which are about emotions. And this is familiar ground to me. All of my dreams take place in bookshops and cinemas. I know that it must have been different for previous generations, perhaps for someone like Colin, who could dream of something like primary experiences, actual encounters, instead of reading about them in a book inside a dream. And then of course there are the generations who came before Colin, some born before the unconscious was invented. What hope for these brave men and women, who were left no apparatus to dream with?

DC: I’ll begin with a technicality: it is true that The Impostor is made in a single shot, but it’s not entirely true that it is without edits. There is one not-quite-hidden but not-usually-noticed dissolve which enables me to present an eighteen-minute take as a nine-minute (hopefully invisible) splitscreen. (I feel uncomfortable saying this, as if I were Hitchcock letting the dead mother out of the bag just because it seemed a fitting thing to do in the middle of a chat with some decent fellow down at the press club.)

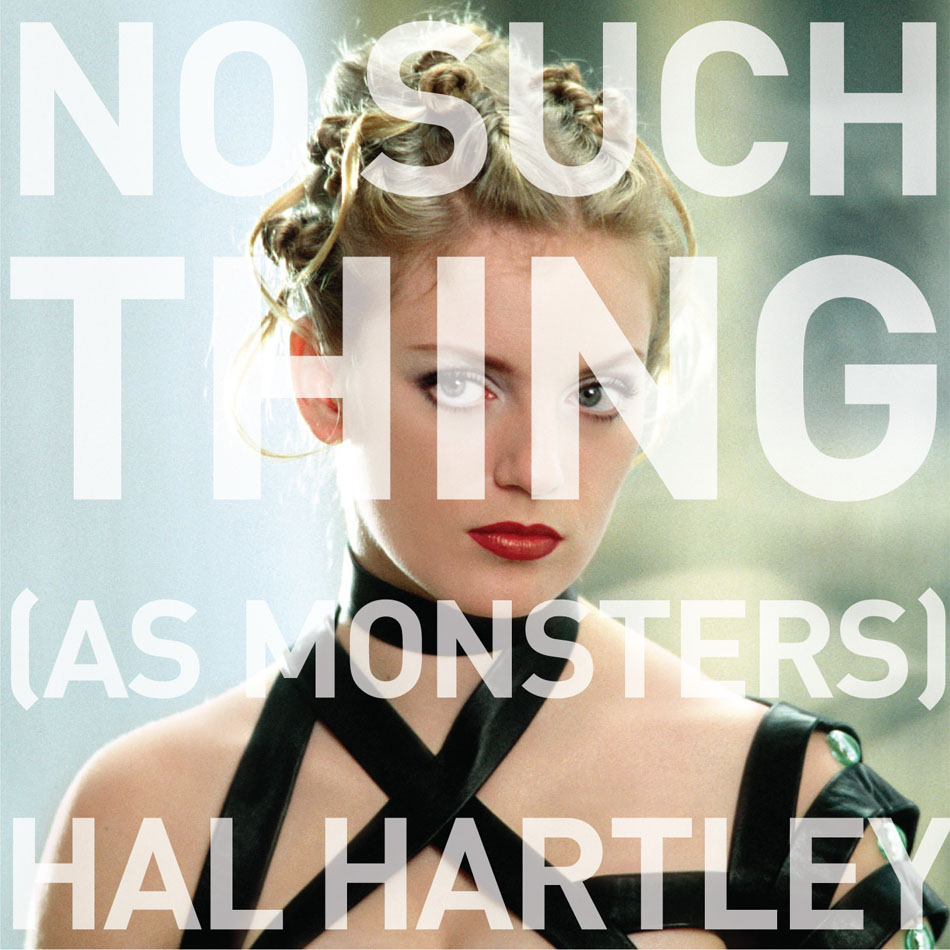

I always run into this problem of doing things I know are alienating not because of any really marvellous reasons that Brecht might have had, but because that’s the approach I identify with. The alienating tactic isn’t alienating to me, not at all; it’s the expression of how I feel about the material. Hal Hartley said something about this which I thought I would quote only briefly, but I got carried away in my transcribing as I noticed how close he comes to describing not only my (perhaps, admittedly, retroactive) intent for The Impostor but also the video’s content:

HARTLEY: I’m less interested in manipulating the audience’s psychological and emotional connection to the characters than I am in really focusing their attention on the event of becoming interested in these actors playing these roles; I’m almost aspiring to have the audience moved by virtue of recognizing they’re all in one big room with a strip of film passing through the projector. It’s like a laboratory experiment as well. I’m the scientist, perhaps, and I say, ‘Witness—I am going to tell you everything in this movie, how it will end, what’s going to happen, etc., and you’re still going to be moved. You’re going to become involved with these people even though you know this is all fake.’ You see, to me, this capacity of fiction is a kind of miracle. But whatever it is, it resides in us. Human beings have the ability to let fiction do this to themselves. I also think that where this miracle works is in fiction that does not depend exclusively on sentiment.

GRAHAM FULLER: Although it does require us to suspend disbelief and our desire to consume something that makes us suspend disbelief.

HARTLEY: That’s why it works. It’s absolutely our ability and willingness to suspend our disbelief that makes a more immediate contact between film and viewer possible, because it admits that people want to suspend their disbelief. Not admitting this ushers in cheap sentimentality: emotional effect as opposed to emotional involvement.

It seems I internalized it enough that I applied its method to an artifact composed of its own method’s metaphorical ingredients: the introductory remarks give away the ending, the lab scientist foregrounds the filmstrip’s passing, and both onscreen figures reveal their identities’ shared artifice.

MH: What a terrific answer, even your side steppings are terrific. Do hope you are not feeling that my intention is to keep you spinning round the centrifuge until all your features flatten into some grotesque, uniform, two dimensional space. The grotesque is best appreciated in three dimensions, don’t you think?

DC: In Borges’ Funes the Memorious, the narrator has a conversation with a man incapable of forgetting anything, and expresses his anxiety thus: “I thought that each of my words (that each of my movements) would persist in his implacable memory; I was benumbed by the fear of multiplying useless gestures.” I know this interview is creeping along, and it’s because of the anxiety I feel in committing words to a likely life beyond my control. This anxiety manifests as half compulsion to make the words right, half reticence to make them at all.

So for now I’ll keep putting it off by resurrecting the words of others, throwing zombie texts up in front of myself as a front line of defence. Atom Egoyan wrote, in the foreword to your Fringe Film in Canada book: “…is the traditional grammar of cinema a direct expression of how we dream? Do we dream in multi-angle coverage, with static masters, close-ups, tracking shots, and pans? Do we never cross the magical axis, except when we wake out of our sleep in terror? Is this why the language of early cinema came so quickly—because we’ve been playing it inside our heads forever?”