Paul Wong’s East Van: John

Artist’s Talk with Paul Wong and John Greyson (Vtape, Toronto, October 25, 2008)

Vtape proudly presents the Toronto premiere of a new work by Vancouver-based pioneer and Governor General’s award winner, Paul Wong. East Van: John (38 minutes 2008) is an intimate portrait of a neighborhood in transition, as the new owners of a house on Vancouver’s east side survey their badly burned property prior to renovating and the former owner casually chats with Wong, a long time friend – all on camera. The resulting work is a tale of connectedness through friendship, kinship and addiction. Curated by Lisa Steele, Creative Director, Vtape

Paul Wong: I’m really excited to be here in Toronto at Vtape. It’s like coming home. I’m on tour presenting some of the 12 new works we’ve finished in the last two months. Today is the official premiere of East Van: John, which I’ve only shown in my studio, so I’m going to sit down and watch it with you. This is a return to basics. It’s a return to working the way I used to work, spontaneously and intuitively, looking at what’s immediately in front of me. This work is really from the hood I grew up in. Let’s watch and then we’ll chat after.

East Van: John screens

John Greyson: Welcome to part two with Paul Wong. Paul, let’s start by placing this work in context. You’ve been making and remaking these East Van videos in the last couple of years. East Van: John is part of a larger project, could you speak about that?

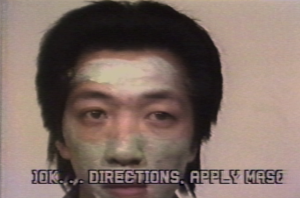

Paul Wong: I live on Main Street in East Vancouver. It’s the same neighborhood I grew up in, and where my earliest work was made. The camera has returned to my immediate environment, as opposed to the more formalized production styles of managing crews and large live events. I’ve gone back to the original portapack ideal, have-camera-will-travel, here it is. I have hundreds of recordings, hundreds of tapes I’ve never looked at. Although this one was shot more recently, some of the other stuff I’ve been pulling out dates back thirty years or more. I’ve been literally going through boxes and finding tapes, wondering, “What’s on this one?” I shot a lot of this camcorder material before, during and after my official projects. It’s a goldmine. A lot of the works I’m going to be showing over the next month are made from these little cassettes that have fallen between things, and East Van: John comes out of this practice. Vera (Frenkel) was just commenting on the fluidity of my camera. These small, fabulous camcorders really are an extension of my body. It’s not even my eye anymore.

JG: In the video we learn that you’ve known John for quite a while. There’s an ongoing history between the two of you, and new discoveries are made while the camera rolls. For instance, he tells a story about your 14-year-old nephew. How did you first meet John?

PW: John and I know each other through brothers, sisters, aunts, boyfriends, cafes, the laundromat. And of course, he also worked with my sister-in-law. I know Rick Erickson, who lives across the street, a man who idolized John when he was growing up. John was five or six years older than Rick, a brilliant, funny, happening kind of guy.

I grew up and lived in an urban environment that has become very transient now. Everyone moves into a neighborhood and then moves on and out. John’s family has been there for a couple of generations, he’s the last person on the block. On the day he sold his house, I had a feeling I better go over there and see what happens. The tape is about a neighborhood in transition.

JG: What has happened to John since?

PW: The new owners, Dennis and Barb McDonald, finally got him out of there a number of weeks after possession, by offering to help him move a five-ton truck full of stuff to his place on Saturna Island. He stayed less than 24 hours before coming back to town and moving in with another fellow who lives a few blocks from his place who is a junkie. John filled up his garage too, and stayed there on and off for about half a year. Six months ago, I went for a visit and recorded that place because I saw on the news that it had also caught on fire and burned to the ground. John had moved on six months prior to that because the other fellow was fed up with him. He wasn’t the best house guest.

I was actually going to call Elaine, who keeps track of where John is, knowing you might ask this question, but I haven’t. I suspect he might be living in the valley with his sister. John is a multi-millionaire. He made $800,000 on the sale of the house, but he also retired after working for the government for many years. And he inherited everything his mother had, so he’s probably got a couple of million dollars.

JG: As much as the tape is a portrait of John, it’s also a portrait of a house, a portrait of real estate in Vancouver, and an economy that has a very complex relation to the new owners and John. A perverse double bill might pair it with Grey Gardens (1975) by Albert and David Maysles. I was thinking of Little Edie singing Tea for Two, versus the song sung by SpongeBob Square Pants in your tape: sort of East Hampton versus East Van. You came out of a generation that rejected the cinema verité movement and yet you take a Maysles-like approach in this tape. Can you talk about the differences between your approaches?

PW: You tell me what the differences are.

JG: The Maysles didn’t talk as much behind the camera as you do, and your continuing interactions make it a profoundly different experience. People have seen so much silent verité that asks the subject to speak for the maker. Your engagements are complicated and profound. There’s all sorts of information that is half revealed, but then you don’t pursue it. Often stories aren’t wrapped up or definitively concluded.

PW: My cinema verité influences come from Susan and Alan Raymond who made An American Family: The Story of the Louds back in 1973. They were the first to use portapacks. Their thing was to let the subject speak while remaining silent. The Maysles use film. I use a little camcorder and that technology is the main difference between us. I can afford to let things roll. And because the camera is also my body, I’m this close to him. (Paul steps close to John) It’s an intimate relationship. I don’t like to use the zoom, I’d rather bring the camera closer physically.

JG: There are some very long, beautiful shots in real time, like when you’re making your way through the back yard and discover him pissing against the house. There were times when you cut, sometimes in the middle of scenes, and other times when you chose to let the action play out. What guided those choices?

PW: This began as a 55 minute recording on one tape. There were tapes shot before, after, and the next day, and the year before the fire happened which destroyed much of his house. I haven’t even looked at those. I saw this tape, and decided to trim it from 55 minutes to 38 minutes. And even that might have been cutting too much. Do you think it was too long? It was initially edited in-camera, and a number of people who came to the studio were not able to stop watching it, but I found it long. The cuts were made to tighten it up, but nothing has been moved out of order. It’s just been pared down. Shaped.

JG: During the edit, did you go in with a plan, or was it very intuitive?

PW: There was no set plan. Sometimes I felt, “I don’t need more of that.” Or I forgot to turn the camera off. 38 minutes remain out of 55, how many minutes have I trimmed? What’s the percentage?

Audience member: A third.

PW: I’ve trimmed a third, that’s quite a lot.

JG: The other piece I thought of while John smokes crack was Gillian Wearing’s Drunk (1999). She famously invited a group of South London street drinkers to come to her studio and drink in front of the camera. She took a very observational approach, there was no on-camera interactions with the artist, or any camera movement. It was presented as a 23-minute, three-screen installation with nearly sub-audible audio. This exploded into a firestorm of ethics, though this is by no means the first time that an artist has been embroiled in controversy because of their relationship to addictive behaviour. How did you think through those ethical mazes?

PW: It’s interesting that you bring up Gillian Wearing, because we both had solo exhibitions at the Vancouver Art Gallery at the same time in 2002. She was showing Drunk and a couple of other related works, which brought her the Turner prize. I found her unbearable. After meeting her, and seeing the work, it didn’t gel. Her practice comes out of a fraught, overly-thought-out, not-very-complex position. I’m not a huge fan.

JG: What about the issues between you and John?

PW: He was a willing candidate, and as you can see, he’s no dummy. I don’t have a release form signed from him. I’m more concerned about the lovely couple, even though they know me really well because they’re my in-laws. Everyone knows that if you’re around and I’ve got a camera rolling… They came onto that site knowing I was going to be there that day. The next day we had a discussion about it over coffee and she started to freak out. “I’m a school teacher and I can’t be seen in this work.” I said, “Whatever,” and we haven’t discussed it since.

They’re not actually friends of John. Though they say that in the tape, they were introduced to him by a mutual friend. They didn’t live in that neighborhood. They lived ten blocks from where we grew up. My good friend Rick has been offered that house three times over the last six years. He refused the house for $100,000, $200,000, $300,000. Because as an old friend, and someone who lives in the neighborhood, he was very concerned, as I was, about where John would go? Even though he’s got a couple of million dollars in his pocket, the neighbours, and all those who had moved in more recently, couldn’t tolerate him. They wanted the character houses without the characters in them. He can’t move into a condo, he wouldn’t make it past the strata council. People barely tolerated him because he’d always been there, but now that he’s displaced, where does he go? He had a sense of belonging because he’d been there so long. Neighbourhoods undergoing these quick transitions lose their sense of history and knowing.

JG: The tape immerses us in a very damaged and derelict house space, burned by fire and never repaired, which is suddenly transformed in the closing shot of the movie which you roll credits over. You walk up the stairs and put your camera to the front door where we see completely renovated interiors. Every trace of the fire, and John’s family for that matter, has been erased. The final shot expands the story, and resettles the house inside a city, and its larger schemes of mortgages and real estate developments and class relations. How much time elapsed between the body of the tape and this final sequence?

PW: When did we shoot that Brian? About two weeks ago?

Brian Gotro: About a month and a half ago.

PW: So the gap between was over a year.

JG: One of the main differences between you and the verité makers is that they keep themselves outside the arena of representation. Often, they’re coming from outside. But there’s no outside for you. How much are you aware of putting forward yourself as a subject?

PW: In the 70s and 80s I deliberately stood in front of the camera. I was subject, body, performance, youth, angry punk. As the productions got bigger I removed myself and I was very aware of this choice. But as I said, a lot of these new tapes come from material made before, during and after official productions. And I’ve developed a studio practice in the past year, working with these old tapes, recognizing that I’m a master of my own craft and the expertise that exists in my little world. It’s taken me three decades to get here. So when I decide to pick up a camera and go like this (he holds arm out in air), I’m not just picking up a camera, I’ve done it hundreds of times. I know the room, I know where people are standing and sitting. I know what direction the microphone is pointing. It just comes.

JG: Michael Turner wrote about your tape this way “Social (and psychological) activism has always played a part in Wong’s videos, photo-collages and performances, and East Van: John is among his most important works to date. However, what struck me most about this video was not the sociological commentary, but Wong’s camera work, his ability to create gorgeous tableaux, both pictorial and abstract, always with an awareness of where the light is and how it can be employed — or ignored — to effect. In East Van: John, Wong follows the irrational path of an intelligent and insightful man, one that takes the artist through his subject’s former home during a series of impossibly long takes, each one a continuous line drawing (the camera is rarely turned off). Wong is expert at anticipating his subject’s movements, and in doing so proves that, as much as he is influencing those movements, he is also in tune with those beyond his control.”

Turner makes a compelling and passionate argument for you as a visual artist and videographer. I think we always tend to focus on content, on what you’re talking about, and sometimes forget about your eye. When you were shooting John, was the work intuitive because you brought thirty years of framing to it, or were there strategies at play?

PW: It was very intuitive, responding to the subject and the site. And I knew this was really interesting material wherever it would go. It may not go anywhere, but I recognized this as a special day, and this was a good enough reason to turn on the camera. It’s also made possible by having these little camcorders that are better than the $100,000 cameras from 20 years ago. Because today’s cameras are faster, smaller, smarter and lighter, we can do these things.

JG: Shall we ask the audience for questions? I’m sure people have responses.

Vera Frenkel: I have a small question. The schoolteacher and her second comment about bones, was that addressed to the burned down house?

PW: She says that the house has good bones. She means it has a good frame, we can fix it up. She had not seen the house before that, it was her first viewing.

VF: In Grey Gardens, the filmmakers treat both mother and daughter, big Edie and little Edie, as spectacle. There isn’t a moment of that in your work. One of the things that really interested me was the chant and response of the dialogue. He would speak and you would reflect back to him what he had said, or slightly re-interpret what he was saying. There was something song-like about your exchange.

PW: I’m reframing a lot of what he’s saying because I want him to say more through reiteration. Get him to go a little further. I’m responding to a subject, as opposed to pushing a subject. This is where we’re going with this conversation. If we’re talking about black and white, I would ask, “What’s that about the white thing again?”

Lisa Steele: You’re like that in real life, that’s your form of exchange. You go into a restaurant or a café and you’re always talking to people. You do the Paul Wong thing.

Vera Frenkel: Apart from everything else that John (Greyson) has pointed out about the larger political and moral issues, I think it’s a tape about trust. I’m one of the people who’s very quick to enter the firestorm of ethics and I didn’t feel troubled at all.

PW: I’m glad because trust underlies my relationship with him and with other subjects. I don’t feel like I need a release form.

Narendra Pachkhede: You have at least three separate schools which are embodied in your work: ethnographic practice, video art and documentary. You enter into a discourse around spontaneity that makes it easy to get into your work.

PW: It’s nice to work without matting and framing in advance. So much art comes out of the same professional finishing schools where everything is pre-conceived and then produced. Been there, done that, I’m going to do that again. At this time, things are just happening, so let them happen. It is what it is. I just don’t think about a lot of these questions, I’m busy doing stuff. I just had a meeting with a gallery who asked, “How would you like to present this work?” I didn’t have an answer at first. And then finally I said, “You know what? Throw a bunch of these things together in different shapes and sizes in the same room. The work isn’t architectural, so as long as the viewers are comfortable, and the sound is good, it’s fine.” I hadn’t really thought of how it might appear in this prestigious gallery setting. I hadn’t got to that point yet. Sometimes it’s nice simply to let the work come out.

Sara Diamond: This tape reminds me of what’s available on Youtube because there’s a youthful, apparently artless approach, and it’s interesting to see you inside that discourse. But I also think it matters to know your history when reading this work. A lot of the questions it raises come out of questions from the past. I’m thinking about the improvised forms of the Main Street Tapes (1976-79), or Confused: Sexual Views (1984), an installation that features a set of spontaneous interviews. I’m also aware of the location of that neighborhood which provides me with a geographic and economic context.

PW: Some people in this room don’t know my work at all. If East Van: John was made by someone you didn’t know at all, are you saying the work would not hold?

Sara Diamond: No, but I think you’re very contextualized as an artist. I’m not saying the work wouldn’t hold, it would just be something very different if it had been made by someone who was an outsider, and who had created an intimacy designed for the project.

John Greyson: I think it’s amazing how self-contained the tape is. Many of the ethical questions raised in the tape are actually answered within the journey of a single day, seen in 38 minutes. They aren’t answered with any sense of closure or definitive conclusion, but there is the persistent sense that they are being addressed and engaged. At the heart of this tape is the relationship between Paul and John. It’s clear that their conversation is one of a series of conversations, on and off camera, which becomes part of a larger neighborhood portrait.

Terry McGlade: Like Sara, I have a long history with this man, and I feel there is closure for you in this neighborhood now. This man has been cast adrift, and as you said earlier, you don’t live in your studio anymore. You’ve moved out of this neighborhood, so what’s happened to John is also what’s happened in your own life.

PW: (pulls a face, everyone laughs) Careful about what you say on the phone. (more laughter) I have moved away from 20th and Main, mainly to separate life and work after all these years. All the work is still coming out of there. It’s been so fantastic for the last year and a half to finally be able to do that.

Terry McGlade: The tape stands on its own, whether the viewer knows you, or the neighborhood, or not. It’s a fascinating project, and there’s probably a lot more in the tapes you haven’t seen yet. It could be brought out as a reality television series. John Jeffries is a character I keep wondering about: what happened to him? Why is he an alcoholic crack head?

Zainub Verjee: When you come to this country, people don’t know who you are. Even if I’ve known someone for 25 years they don’t know where I’ve left, and this speaks to a fear and homogenization that is central to the Canadian experience.

Nina Czegledy: I completely enjoyed this work. The mediation aspect comes down to a minimum. So much independent media work is presented in a schematic, according to a form. This is something which comes through so straight forwardly. It’s very refreshing, it’s so unusual.

Audience: You’ve accumulated many intimate tapes throughout your life. Has the act of collecting these tapes informed your sense of territoriality in your neighborhood?

PW: I’ve never even looked at most of the hundreds of recordings I’ve done. They’re slowly being collected by format which is a daunting task. Now that the studio is semi-organized, I’ve had curators come by and say, “Look at this archive!” They just give me a heart attack, I want them to go away. I’m getting to it, one frame, one tape at a time. That’s one of the beauties of being 103 years old, this collection has now become a palette, and in my new studio practice I can mix and match and look and feel and re-live and see.

For instance, I’ve just sent off 24 photographs that are being exhibited in Ottawa. They were discovered from 2000 colour slides that I shot on my first trip to China in 1982. They’d been stuffed away until earlier this year. I made an initial selection of 200 prints, that were scanned and workprints were made. Out of these I produced 24 framed photographs.

These were from my first Chinese trip that I took with my mother. You weren’t allowed to bring in television cameras and there really weren’t very good camcorders, there was only VHS. So I brought a super-8 film camera, an audio deck, 35mm colour and black and white, and a lot of journals and Polaroids. Not only was my technology fragmented, I was in such culture shock, that when I got back I had all these bits and pieces that I just stuck in a box. In 1986, I went back and sat in one place with my high-8 camcorder and a still camera, and what came out of that was Ordinary Shadows, Chinese Shade (1989). Now using digital equipment, I can fuse all the older technologies together and put them onto one platform.

Audience: It’s impossible to watch this work without thinking of ethics. I think that your sensitivity to John, and being respectful of his space and behaviour without imposing any kind of judgment, is very important. The context of his moving out gives a lot of justification as well. I was wondering if you think your work is documentary or visual art, and about the relation between those two genres?

PW: I call it non-fiction. I’ve never been given much respect by the documentary community or the film community. I just do what I do. For me it’s always a problem to be framed that way. Every time I’ve tried to go to those parties no one talks to me. So I’m making my own party.

Paul Wong’s video career spans some 30 years. His work has been shown in exhibitions and festivals around the world, including London, Paris and Hong Kong. He has had extensive screenings at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In 1996, the National Gallery of Canada mounted the solo exhibition, On Becoming a Man. In 2003, Hungry Ghosts was presented in the Extra 50 Section of the Venice Biennale. In addition to video production, Paul Wong was instrumental in the founding of two artist-run centres in Vancouver: Satellite Video Exchange (Video-In) in 1973 and On Edge in 1985. In recognition of his contributions to the video and media arts, Paul Wong received the Bell Canada Award in Video Art in 1992 and the CHUM-NFB Expression Award celebrating diversity in the arts in 2003. He was one of seven recipients of the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts in 2005. His work is included in major national and international collections, including the National Gallery of Canada and MoMA in New York. Born in Prince Rupert, B.C., he now lives in Vancouver. In 2008, he launched a new project ONMAIN, a street-front space for the display of artists’ projects in Vancouver. In November, Paul Wong was the spotlight artist for the 2008 REELASIAN International Film Festival, Nov. 12-16, 2008 where his work Perfect Day won NFB BEST CANADIAN FILM OR VIDEO AWARD.