Phil

Everything he touches turns into his family. His friends and colleagues, he greets us with a pressing of the flesh, chest against chest, the meat warms together, turns together. At the moment of meeting he pulls me towards him, and in this gesture, repeated time and again, he asks us to regather the many times before this one. We are never all here, in this moment, too much has already passed for that. Our words, the way he looks into my face (are you still there?) and then away again before he continues the story (like me he can’t bear up into the full attention of the receiver while speaking, he needs to look away, to let the eyes look inwards while the mouth points out). All this is happening again. It’s a way we have of remembering.

I don’t think they used words like artist when he grew up. Feedlot and meat packing and carcass and bone but not artist. That wouldn’t come until years later, almost as a kind of default. It wasn’t something he aspired to, instead, being an artist is something Phil backed into. Oh, where am I now? Being an artist meant doing things your own way, finding out for yourself, never mind trying to break the rules or please or displease anybody. It didn’t matter to him where the lines were or the way things used to be done, he was just trying to find a shape for his experience and that led him into small rooms, and he was taken with what he found there. He only learned later that the shape and size of those rooms changed what could be found, but by the time he had that locked it was ok. He had a hunch it would be alright and it’s been alright. As long as I’ve known him he’s worked off his hunches, his instincts. Others have money or scripts or five star actors. Phil has a compass inside and he follows it right or wrong.

In his movies Phil returns to the family again and again. Pictures of home. In his first college produced short On the Pond he puts a microphone into the room while he dishes a family slide show and records the response. Life happens, and he is there moving alongside, both part of and apart from the group. In passing through/torn formations, he takes up residence on both sides of the ocean, drawing together (while keeping apart) the Czech and Canadian sides of his family, circling around the absent figure of his uncle Wally, pool God, street hustler, the monster who cannot be shown. Phil convenes the family as a way to contend with the death of too many around him. Huddled together in this last place, the river of his youth become a suicide site, his partner Marion dead of cancer. He is determined to show memory at work, to make diary moments and stitch them together (his montage produces a family of pictures, a family album).

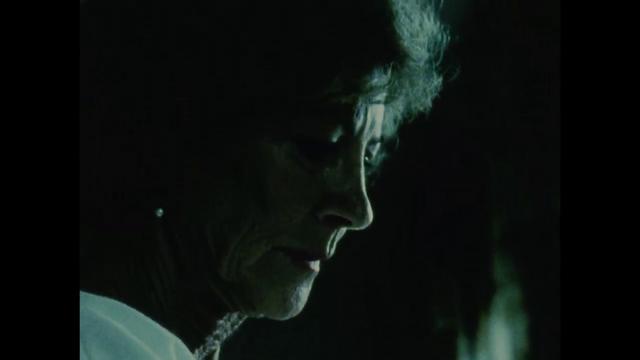

There are no fathers in this family. The fathers have faded away (they smile and nod and say yes, sure, that’s fine, they are not the law but acquiescence to things as they are). Though the specter of the mother (talking, trembling, pulled down from a terrible height, carrier of a mysterious darkness) continues to haunt us in our dreams of waking and sleeping. Mother are you? Can you? Will you be alright? Will be ever be alright again?

He is not afraid to let time seep into his work. This one took years. This one took more than years, all his life. And still it is going on. He stops to gather another moment and place it next to another moment, years earlier, the red drapes, the butterflies gathering after her death, the pyramids opening, the road which ends at the beach. How fortunate I have been to be alongside him, sometimes, on occasion, when he is thinking through these confusions of past and present and his refusal to forget. We need these pictures more than ever now so that we might become part of this family of remembrance.

Originally published in: Rivers of Time: The Films of Philip Hoffman, ed. Tom McSorley (2008)

Philip Hoffman: Pictures of Home (an interview) (1996)

MH: Any early experiences with pictures you can remember?

PH: The first one I can think of was my grandmother, who used to shoot from the hip, without looking through the viewfinder. These low angle shots always turned out and made us look as big as John Wayne. That was the perfect size when we were little. I didn’t think of it until years later when I realized I was shooting like that sometimes, using the body to find the picture. I had a box camera for years but didn’t get into photography until I met Richard Kerr. He was a couple of years older than me and was going out with my sister. We set up a darkroom in my basement and figured out how to work it ourselves. I was writing poetry, but never showed it to anyone. The photography was different. It was a language I could use to talk to people because I didn’t have words. I was shooting a lot of family stuff — moments of everyday life. I played hockey and tried the accordion unsuccessfully because there were always rules. I was made to play scales which gave me an ear for rhythm, but killed the play in it. Kitchener was a very business-oriented city; you had to look around to feed your interests. I managed to find small pockets where I could work, and those were private places, caves. That’s where I did the writing and the photography. I went into business in my first year of university which was just remote control — everyone in the Hoffman family went into business. But after one year, that was enough, and I took English literature and some film courses, still trying to decide what to do. To support myself I was working in a factory making boxes and figuring out all week what I’d do at the weekend farm house. I would go up with friends and get blasted and shoot these crazy skits on super-8. There’s a rift between what the poet desired and what I thought was desired of me: to be a good citizen of Kitchener-Waterloo. It’s just driven into you there.

MH: Were you expected to work at Hoffman’s Meats?

PH: My grandfather expected me to. I was Philip III, you know. [laughs] I was kind of the heir. My father always wanted to be something else, but he had to work in the factory. His father was one of those staunch Germans, so he never got a chance to do what he wanted. He was quite open to letting me go, giving me the chance he never had. When he was selling the business he asked if I wanted in, and I told him no. Then I decided to go to film school. I tried York and Queen’s, which dropped me because of my business marks. Then I called up the chairperson at Sheridan College, and I was so welcomed that it seemed like the place to go. Richard had been there a year already.

MH: That’s where you made On The Pond (9 min b/w 1978)?

PH: Yes. It was a personal documentary because it makes sense to begin with something you know. It wasn’t so different from the kinds of writing and photography I’d done up to that point, which dealt directly with people around me. On The Pond began with a slide show. I was fairly quiet in the family. I had three sisters who were a couple of years older than me — triplets. They garnered lots of attention. But this was my birthday, so I knew I had the full attention of the family. I miked the whole room and showed slides. I constructed another slide show for the film and cut the comments down from a couple of hours to a few minutes. The slides showed moments with the family. There’s one picture taken from behind my mother. My dad’s looking off in the distance as if he’s discovering some new world. We were out in the bush where we would go for walks. In the film you hear voices saying, “Oh do you remember when we went out on that walk?” And then to my mother, “Oh, that’s when you were feeling lousy.” Except it’s not “feeling lousy”; there’s an incredible amount of trauma which is being dismissed, and the photo shows the shadow of her sickness. You can hear the way her memory is being taken away, how her voice is being levelled. We were taking “good care” of her pain. And then someone says, “Oh look, there’s Phil and he’s smiling,” because I’m smiling in the corner of the picture. So, what’s taken up isn’t my mother’s problems, but the face I made for them. The smile has to do with pleasing her, hoping to make things better. So everything’s there in that photograph. It was shot from the hip, unposed, and it was exciting going through these photos for clues to a past I’d slept through. I think childhood is so traumatic we sleep through most of it.

MH: Was the whole film going to be photographs?

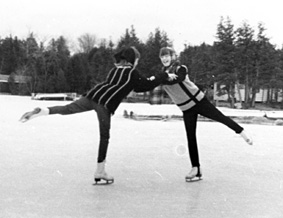

PH: No, I wanted to make a kind of docudrama. I got my cousin to play me as a little boy, getting up early, skating out on the ice, stick handling with the dog. Then the social space enters in the soundtrack, breaking his solitude — you hear the coach yelling and other voices while the boy does pushups alone on the ice.

MH: The film moves between these two arenas — between hockey and the family — as if you have to choose one or the other, or that hockey was a way to leave home.

PH: That’s what happened in my life — the year I made On The Pond I quit hockey. I was playing for the college team, and we had an exhibition game at Kent State where there was a big demonstration. The university was trying to build a gym on the ground where the students had been gunned down. There were cops on horseback trying to gas the demonstrators, and I grabbed a camera and filmed it. That was the point where I left hockey. It was becoming apparent that hockey players weren’t the people I wanted to spend time with. The competition was so draining. So I simply transferred the energy I was putting toward sports into filmmaking. I finished On the Pond in a very heavy Marxist time, and some people were taking a lot of knocks for making films about their own experiences. “Personal” filmmaking was considered self-indulgent. But now things have come round again. Now you can’t just run out and point a camera at someone. Personal work wasn’t thought of as political back then, but to my mind it’s the most political.

MH: How did The Road Ended at the Beach (33 min 1983) start?

PH: Before I went to Sheridan I used to go on trips through Canada. I’d work the first part of the summer then travel for the last month and go back to school. In those days, in my late teens, I carried a super-8 camera with me just to shoot stuff, not thinking or knowing anything about making films. While I was at Sheridan, I continued travelling and collecting footage and called it Road Journals — it was an ongoing sketch pad. After school ended, I planned a trip with some cameras and sound gear, and this became the central trip the others would weave in and out of. Jim McMurray and I started in Ann Arbor because that’s where the van was, then drove north to Kitchener to pick up Richard Kerr.

Then we headed east and visited Robert Frank in Cape Breton. And Danny, a friend who’d gone to school with us, wanted to make films, but got dragged down with his life in Nova Scotia. You see this idyllic setting with the dogs playing in the water and then he says, “Well I have to work in the fish plant — you have to do that if you want to live out here.” The trip was staged — we’d travelled together in the past — and we were trying to remake what we’d already done, to recapture that feeling. But that didn’t work at all. I’d known Richard for ten years; it would have been different if we’d gone five years earlier, because then we were in the maturity of our relation. The same with Jim. All that comes through in the film. This isn’t Highway 61 or Roadkill because the romance is gone. We’re travelling through a cold Canadian summer and not meeting any “girls.” [laughs] It’s a different kind of journey. By the late seventies the road film was dead. And these three guys can’t really talk with each other. We’re all waiting on an experience that isn’t coming and no one’s sure why. It has a lot to do with how men relate to each other, dealing with outer realities, getting the job done. Filmmaker Mark Rappapport said that it’s a record of the time — when Kerouac travelled, things were opening up, but by 1980 everyone was hunkering down for Reagan, everything was closing up. Everyone on this trip is alone and isolated: Frank’s retreated to Mabou, the guys on the road are caught in dead-end jobs, and nobody’s relating to each other in the van.

MH: Road Ended pictures a series of imagined homes to which the film attempts to return. Some of these homes are from past trips, or past times spent with folks in the van, and these are presented against a backdrop of fifties Beat writing, especially Kerouac’s On The Road.

PH: Well, that’s the myth right there — it’s confronted by drawing these different decades together in the editing. The Beats were the fathers I took on the trip, but their roads are closed now. I was attracted to the possibility of spirituality that Kerouac held out through his Zen practice, even though he died an alcoholic far from the lotus tree. But it was one of the first expressions of Eastern culture I’d encountered. It wasn’t the drugs or parties, but those simple moments of description of what’s there in front of him.

MH: Kerouac’s trying to live in the moment, to conjure the present through his writing, and finally to make life that moment…

PH: Kerouac was writing while he was on the move, but when you’re filming the camera gets in the way. Personal relations become performance when a camera is there. Have you ever seen that old Neil Cassady film when he’s on camera? It doesn’t work. The mythology isn’t there. The camera says, “I’m immortalizing you.” The present moment can’t be returned; the camera takes it apart. But you can go off alone with the camera and create energy — like the last scene where I’m dancing on the beach. That kind of thing expresses the Kerouac ideal of pure energy in movement. As far as Robert Frank goes, even though nobody was making photographs like him in the fifties, he was still taking the moment and stealing it from someone. I’ve always had trouble taking pictures of people I don’t know. He had a social reason — he was trying to show America’s spiritual bankruptcy. I was making a personal film. That’s why the photography in Road Ended is so careful, so unlike a road movie. There’s no barging into strange places and waving

cameras around. That was done in cinéma vérité in the sixties, and I have problems with that.

MH: How did Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion (6 min 1984) begin?

PH: There was a reunion of Beat poets in Boulder at “Jack Kerouac’s School of Disembodied Poets,” at least that’s what Ginsberg called it. I drove down with my sister and a friend. Robert Frank was there, and I wanted to ask him if I could use one of his photographs in Road Ended. But every time I tried to talk to him something would happen, some guy would walk up, “Are you really Robert Frank?” Finally, I bumped into him by accident, smashed right into him, and he was his normal humble self. He remembered our dog. So that was fine. I wanted to go to Boulder before going down to Mexico where I had this romantic notion of shooting very simple events — I had been reading haiku. The Bolex is a camera powered by a spring that you wind up and it runs for twenty-eight seconds. I wanted to use the length of its wind as my frame for these haiku shots. The Bolex was perfect because it’s light and doesn’t need batteries, and I’d worked with it so often I knew when the shot would end. I used its so-called limitation to my own advantage as a structuring principle. I went with ten minutes of film. I’d met Adriana Peña on one of my Road Ended trips and was going down to see her. She was taking me around, and I became involved with her family. It was a bit strange. She was showing her family the man she was maybe going to marry, and then I realized that this was perhaps not such a good idea. [laughs]

MH: Can you explain what a haiku is?

PH: Haiku is a three-line poem with a five-seven-five beat structure. It usually describes everyday events. The three images, or lines, go together to form a new expression —Eisenstein used haiku as an inspiration for his ideas about montage. So I shot things for twenty-eight seconds, each shot the same length, and in the midst of this shooting found myself on a bus between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion. The bus stopped, and a woman came screaming across a field. Her little boy had been run over. I watched from inside the bus with the camera in my hand, trying to decide whether to film or not. And that’s what the film becomes. When I got back to Toronto, I decided to try and make a film about that moment without the image.

MH: Why didn’t you film it?

PH: Gut reaction. I can intellectualize it now. I could say: I didn’t want the camera to get in the way of the experience, or I wasn’t ready, or it would have made a lot of people uncomfortable, or I didn’t want to be like some reporter “getting” the scene. In the editing I inserted intertitles which talk about the boy on the road in a bastardized kind of haiku. It has to do with my own working through death. I’ve been taught that death isn’t part of life — it happens on television, or in life as a theatrical event at the funeral parlour with make-up and masks. The title Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion suggests, for me, the passage from death to birth — the bardo state in Buddhist terms. Between these two places is the death of a boy. Jalostotitlan has, in its centre, an ornate graveyard that we passed by on our way to the death. Encarnacion suggests “incarnation,” an embodiment in flesh. Visually the film is bookended with shots in black-and-white. The death is rendered metaphorically in colour superimposition, before the film returns to black-and-white for the last shot, which shows the passing water of a river, the rebirth. I was working on the film in my basement apartment when I heard a religious parade pass by. I went out and filmed it, not sure of how I’d use it or which film it was going into. I count on this kind of coincidence to make my work. I was experimenting with multiple layers of pictures — shooting a roll of blue brick wall, then winding the camera back and letting chance have its way. The work I’d done up to that point had been more representational and used static camerawork, even in my Mexico shooting. My ideas of documentary had been quite traditional, but what I’d learned in Road Ended was that there’s always something outside the frame, and that’s what Somewhere Between is about.

Bart Testa was the first person to offer this work some public attention. He programmed the Grierson Documentary Seminar in 1984, calling it “Systems in Collapse.” The seminar doesn’t happen anymore, but back then it was important in my theoretical development as a filmmaker. There were people making television documentaries and others making experimental work so there were very heated debates. Bart’s programming was critical, and he said he wouldn’t do the seminar unless he could show The Falls by Greenaway. He also invited Road Ended and Somewhere Between. There were people complaining they only had $100,000 to make a film while I was showing Somewhere Between which was shot on three rolls of film. So Bart was making a point by inviting me. At the seminar, my work was paired up with a guy named Don North, a news correspondent who’d made a number of films about Vietnam. There was one bloody massacre after another, and he said that was the stuff they didn’t cut. Then my program came on, which also dealt with death but never showed it. Because television and violent movies have conditioned us to see pictures of death in a certain way, when we see it for real it’s just the same. My film argued that you could deal with another side of death or that the possibility of mourning lies in the unseen.

MH: There’s something very Catholic in this refusal. Death is granted a power because of its secrecy; there’s an awe and mystery that its revelation could only trivialize.

PH: Not showing death wasn’t because of fear, but respect. I didn’t want to barge into its territory, to try to exploit it for my own work. It was a ceremony that didn’t belong to me. I was honoured to be in its presence, but, at the same time, it wasn’t mine. So after the seminar North approached me and said, “Phil, I really enjoyed the discussion, but you know when you were in the editing room, didn’t you just wish you had the footage?” Some things don’t change. I think Peter Greenaway connected with the independent filmmaker in me — the idea of making work with what you have available. He was really moved by Road Ended. He talked about the poetry in the images. I asked if it might be possible to see one of his film shoots and he said sure and wrote me a reference letter. The only way I could arrange financing was through an apprentice program, but he’s not into “learning from the father.” He felt my work would develop on its own. In his letter he said I needed opportunities to make work and that I should get funding to make a film about anything I wanted and that I didn’t need to use a script. That was the other thing, I was working without a script, just collecting images over a long period of time and making sense of them in the editing.

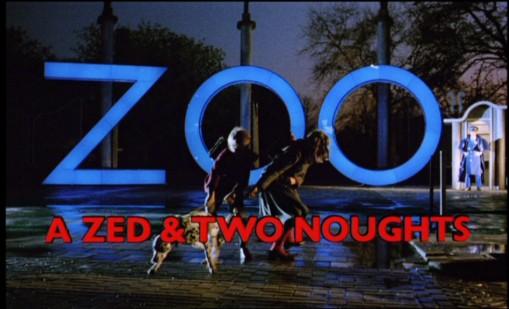

So in the summer of 1985, I got $3,500 to go to Rotterdam and spend two or three months gathering pictures. I had about forty minutes of film. I worked the same way as in the past, shooting about thirty seconds a day, whenever the light and my inclinations met. I shot on and off location while Greenaway was making A Zed and Two Noughts in the Rotterdam zoo. ?O,Zoo! begins with images the narrator says are made by his grandfather who was a newsreel cameraman — it’s a Greenaway-type ruse. Then it shifts into the making of the film around A Zed and Two Noughts. The diary starts with the trip to Holland and fairly mundane images — of animals, a huge wooden apple in the park, a headless statue — while the narrator speaks of what happens before and after the shot, with what’s outside the frame. Then the screen goes black and the narrator speaks: This is another example of the unconscious speaking. I wrote the story after the event happened, then realized it was directly connected to one of the first deaths I experienced. After my grandfather died, my uncle asked me to go to the funeral home and take pictures of him in the casket. I showed up and didn’t know what I was doing there. I’d been making photographs for years and didn’t want to document him in this fake place. But I took the pictures and put the film in the freezer for eight years. In a way, the film was a way to act this out, to return to my grandfather. It keeps coming back in my films so whether I’ve laid him to rest or not…

MH: How does passing through/torn formations (43 min 1988) relate to your previous work?

PH: In terms of my film work, On The Pond relates to my boyhood and family. Road Ended deals with travelling and friends and adolescence. Somewhere Between and ?O,Zoo! deal with fathers and a documentary tradition brought down by fathers from which I’m trying to make something of my own. passing through/torn formations is the first film to deal with my mother’s side of the family — it’s filled with passion and chaos. The previous work features a locked-down camera in confined spaces. But passing through begins with a camera floating through a nursing home, hovering over my mother as she feeds my grandmother Babji. I couldn’t show death in my previous work, but here I had a very close connection. I loved my grandmother very much; she was the first to tell me that dreams were important, so her decline had to be dealt with directly. The film unravels from her; she’s the matriarch. But it doesn’t begin there. It starts with a Chris Dewdney poem called “The Quarry.” A boy opens a rock which has a moth inside, destined for fossilization, and as he opens it, the moth flies out “like dust from a dust devil.” The moth that’s being freed is the uncovering of family history, making it an open, interactive system. My purpose in making the film was to try to return my uncle to the family. He’s a street person who’s been cast out because his mental instability and violence caused a lot of grief. Idealistically, I felt that I would make a film with him and make an interjection into a family history that never moves, where things aren’t spoken.

MH: You remarked earlier that while making ?O,Zoo! you’d assumed some of the form of Greenaway’s work — that this was part of your diary approach. In passing through I felt you’d assumed or mimed your uncle’s demeanour — the film is rife with splits, multiple exposures, simultaneous address, broken subjects, departures, wars, and arguments.

PH: One of the stories my uncle told me was about his accordion. His father made him practice every day because he was going to be a great musician. But the instrument isn’t balanced. You play the melody with your right hand and the bass line with your left, so you have to split your mind in two. He felt that’s what led to his “manic depressive” or “schizophrenic” behaviour. I have a different take on it. I think he had a great capacity as an artist but wasn’t allowed to express it except through the accordion. His parents had come to Canada from Czechoslovakia — at that time, the Austro-Hungarian Empire — and were already in their forties when he was born. He wound up in the pool halls listening to Elvis Presley and playing jazz accordion, but they couldn’t accept that, and this rift grew into a psychosis. He thought it was bad to split your mind. But in order to watch the film you have to split, you have to think in a non-linear way. Because many stories are being told at the same time, the viewer has to choose how to move through it. The form relates not only to his ideas about the accordion but to the way he is, as if I were him.

MH: The film also tries to heal some of these splits, and the central image of this integration is a corner mirror your uncle builds.

PH: He made it because he’d heard someone talk about left/right-brain differences. He felt that when you shave in front of a mirror you’re actually seeing yourself as a reflection — you don’t see yourself as others do. He felt that all the years he’d been shaving helped split him apart, and he could solve this with the corner mirror: two mirrors which reflect into each other. He had to re-learn how to shave because the reflection was the reverse of what he’d grown used to. He felt that ritual would exorcise his demons and heal him. He did the same thing in prison when he rewired an electric organ so all the low notes started at the right and left ends of the keyboard: they were symmetrical and moved to a central note in the middle. Of course, he was the only person who could play that organ. [laughs]

He was trying to unlearn conventions of the past, the way he’d conditioned himself to live. That moment of creation and transformation is the moment of freeing the moth from the rock. It’s the moment where the image comes to the paper when you’re making a photograph. It’s magical because you’re totally in the present watching what’s becoming. That’s what I got from him, that living instant, but on the other hand there were other things attached to him that became too difficult. He was like the elephant in ?O,Zoo!, or the dead boy in Somewhere Between — the image that couldn’t be looked at because he would be judged. So he’s hardly shown. My brother Philip died at birth. My uncle Wally wasn’t much older than me, so he became the brother I never had. Wally was born during the Second World War, while my grandmother was in great anguish over her brothers and sisters. While she was pregnant she grew a huge boil on her neck, and I use this as a metaphor in the film — as a poison coming to the surface. My grandmother was hearing stories about her brother’s wife being raped by Russians and Nazis as they went through the country. After the war, my grandmother, mother, and Wally went back to visit. I guess Wally was about five. There were still blood-stained walls and ruins, and Wally got sick. No one went again until I did in 1984. That’s the trip I show in the film where I asked my grandmother’s sister to tell me what happened with Uncle Janyk, who was shot by his brother. There was an argument over land. The son had built a house on land which had been promised to him but the father refused to sell it to him. He wanted to own his son. So the son killed the father. All these stories are strewn through the film, which has been deliberately made so you can’t follow it like a Roots chronology.

I should say something about Marian McMahon’s involvement with the film. With my life. We’ve been together a long time now, and she’s changed the way I look at things, and I thought it was important to have her present in the film. The film ends with her voice making a very simple statement: “When I was eight years old, I skipped a flat stone six times across the smooth surface of Lake Kashagawigamog.” This recalls the Dewdney poem at the beginning of the film, which is also spoken in darkness. Her speaking returns the film to Canada, or to a pre-Canadian continent, because Kashagawigamog is a Native word. So even though all these ethnic migrations are going on, both ends of the film deal with a time before the Europeans came. Dewdney’s poem refers to geological time, and Marian’s to a time belonging to the Natives. The kind of relentless uncovering that the film attempts is something I learned from her. I had been working with “personal” film, so these interests attracted each other, but she showed me a way to go further. She’s a companion in this uncovering of our own histories. She taught me that our past is living in our present, in our bodies, and that it’s worth the dig. If you don’t uncover the past, you freeze up. There’s pain involved in both states but the continued uncovering is alive — it feeds a living cinema.

MH: How did river (15 min b/w 1978-89) begin?

PH: It started off as a shooting exercise when I was studying film at Sheridan. The idea was simply to make a film that would be edited in-camera. So I went to the Saugeen River with a Bolex and a Rex Fader that allowed me to dissolve from one shot to the next. Richard Kerr steered the boat. The Saugeen goes through Lake McCullough, where my parents have a cottage, and we’d go up there in the summer. I would fish for trout or just drift down the river. I wanted to come back now that I’d decided to work with images instead of fishing poles. To see what was there. I shot parts of the boat, and the water and the light, looked at it and put it away.

Three years later I got hold of a black-and-white video port-a-pack, an old Sony half-inch, open-reel deck. I wanted to drift down the river and let the camera run. The microphone was on the bottom of the boat, which amplified the sound in a weird way — it picked up anything the boat hit. This time I went down the river without anyone paddling; the boat just followed the current while I stood up holding the camera. What ensued was the chaos of the trip. The sound is important because every little nudge and scratch is very loud which contrasts with an idyllic floating-down-the-river scene. To my surprise, when I first showed it, people found this section quite humorous — the person’s struggle in the boat, a confrontation of “romance” with chaos. That became the second section. Then I duped the in-camera edit onto video with a looping soundtrack — instead of seeing the dissolves fade to black, you see the screen it’s being filmed off, which deconstructs the romance of the first scene. That was the third section, and each plays sequentially, one after another, moving on like the river.

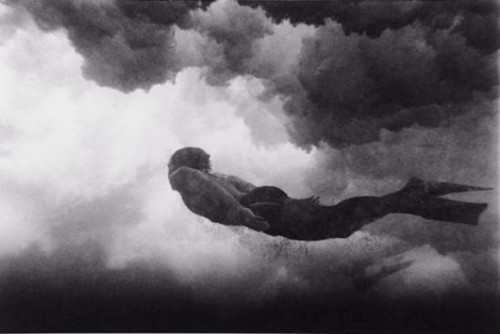

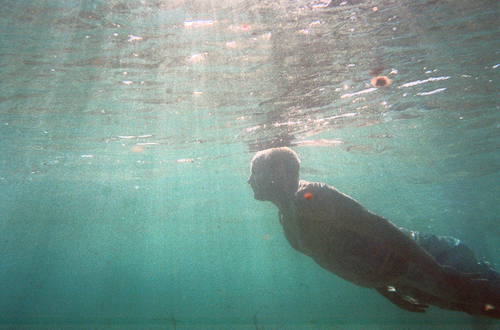

The last scene is shot underwater. I went with a couple of guys who were helping me because they had underwater housing for the Bolex. On the way up, I phoned my mother to tell her I was coming and she said, “Your uncle was found dead by a river, we think he shot himself.” Pretty gruesome. It really coloured my thinking about the river, deciding what to shoot in this last scene. It’s all filmed underwater with a high-contrast stock, and unlike the other sections, which flow smoothly, it’s fast, almost Brakhage-like. In the editing I worked on the death-rebirth motif. Three times the camera moves up into the light, and the film ends with light. Buddhists believe that the Bardo state is the moment where the spirit dissolves into the universe, and it’s commonly represented as light. I felt I needed to mark the death of my uncle because of the way it happened, the way it came to me. The only guide I’ve had in my filmmaking are these so-called coincidences.

MH: I remember when you started working on Kitchener-Berlin (34 min 1990) you said that you’d spent so long working on your mother’s side of the family that you wanted to turn to your father — to tell his story.

PH: I related my visual nature to my father’s side, the silence and image-oriented expression that were a part of my earliest experiments with photography. I used home movies that my uncle shot (my father’s brother). There’s no story, just home movie moments mixed with photographs of Kitchener back when it used to be called Berlin. These are joined with newsreels from the other Berlin during wartime. Then the film re-visits both sites in the present, using a Steadicam camera. It floats over surfaces, looking as if it can move without gravity, gliding in space.

MH: Why the Steadicam?

PH: There’s an obvious kind of spiritual feel to it, because you’re floating in a world where the sky and ground are equivalent. It’s something we can’t do with our bodies, except through technology. So it’s a metaphor for the spirit released. I wanted to contrast that with the low technologies — the home movies which take a familiar form and subject. The Steadicam provides a solitary and other-worldly stance, an emptiness and separation from anything it shows. There’s something that separates the people sitting in front of these old buildings, that separates the remnants of German history from the present, and the camera signals this. This relates to masculinity. The Steadicam is part of the technology that can take us to far-away places or destroy the world. I wanted to show different aspects of technology through the century, using the Steadicam to create a feeling of introspective space where one can look back and account for what’s happened.

MH: Juxtaposed with images of the past, the Steadicam is filled with a sense of returning. Because its movement isn’t attached to a body or person, and its movement is so uniform, it’s as if the ghost of technology had ventured back to visit what it had occasioned, to look over all that’s been constructed in its wake.

PH: Yes, that’s the journey. The Steadicam floats over continents, adding layers until there are three, four, five images over top each other. They show an old Austrian churches, Berlin’s bombing, an orange crane that looks like some technological beast, the Pope shaking hands with Native peoples, and machineries of the city. It builds to a point where the camera moves toward the sky, and then it breaks, overloaded, and the film dips into another strata. I went to the National Film Archives in Ottawa, looking for images of Kitchener during the war. An archivist named Trap Stevens said, “You should look at this old film — it’s quirky.” He pulled it out, and I was really moved by it. It touched something in me. The film was made by Dent Harrison, a British immigrant who came to Canada in the early part of the century. He arrived penniless and went into the bakery business, where he figured out how to cook a lot of bread at once by using rotating ovens. He made enough money to travel and own a movie camera. He made what I think is the first Canadian surrealist film. It pictured a dirigible flight from England to Canada, which I saw as technology coming to North America. I’d already related Kitchener to its German roots in Berlin and suggested how the philosophical bent of these new technologies related to the rise of fascism — how humans tried to become machines. At first, I couldn’t legitimize using Harrison’s footage since it didn’t have to do with Germany, but I realized I was neither German nor English, and that the English presence had been very strong in Kitchener. Harrison crosses the Atlantic in a dirigible and on a boat, and speaks of himself and a double making this travel. He’s split himself in two in order to shoot the trip from two different perspectives. Later, he begins to edit his film and he uses a superimposition of himself, so you see him and his double in the same space. After that, when he’s asleep his double moves out of his body. Then a subtitle reads: “Have you people seen all that I have in my dreams?”

Then my film breaks into another section, which is more meditative, where the technology digs up the earth, using National Film Board footage of miners, interspersed with stuff I shot of a more ethereal nature. There are more home movies and wheat fields and footage I shot in a cave, all defying meaning. The way the images arrive is a surprise — they don’t seem to connect and, formally, they’re hard to follow. In the first section, you expect certain patterns to recur, while the second section tries to deal with images in a way that’s less filled with “meanings”; it moves into a flow of dreams. After screenings of the film some people have spoken about unremembered images from their past. That’s an area I’m working with in my new films. Among the images of the underground, the last picture shows a red dress — the little girl slips into the emulsion — which says to me, “Stay tuned. We’ll see what comes out.” The whole film is a rendering of what I see as my male Germanic side. The first section is a walk through physical realities connected to the effects of technology, the male hand, so it includes the war and the Pope and the co-opting of Native cultures, all glimpsed through an ethereal camera. The second section is an inward journey. It’s that simple. This shift is signaled by Harrison’s old home movie, which begins in a very analytical and documentary fashion and then slides into a dream reality of doubles. The voyage over the Atlantic is linear, but once he’s home, things begin to unravel. That’s the inward journey.

MH: After finishing Kitchener-Berlin, you gathered up all of your work and named it as a cycle. This series of films progresses through the familial and the formal, through a number of documentary styles that seem finally bent on shaking off narrative or any traditionally understood sequencing of events.

PH: It has to do with transformation. When I named this work as a finished cycle, I had to start again, and was as lost as I’d been at the beginning of my making. That’s where I am now. Rick Hancox said the last films I’ve done all look very different. I feel that recently I’ve gone through a lot of changes very fast, and that’s not always easy. You do it with your work, and then there’s your life. So to imagine work in a cycle is useful. Finishing closed a way of working with the past, of dealing with the uncovering of family history. I’ll always be able to return to that, but now it’s time to make something else.

I went back to shooting super-8 without a plan or film in mind. This started in Banff where the first films I ever shot — some of the super-8 footage in Road Ended — had been made. I returned in 1989 and new ideas came up. Two ways of shooting developed. One came out of the haikus of Somewhere Between, shooting events of everyday life in a static frame, but this time in super-8. The other way was a single-frame zoom. Maybe I’m contriving this new cycle, but it’s a path to follow in the midst of all this chaos. The single frame shooting will find its way into Chimera (15 min 1996), while the haiku project is called Opening Series. The idea is to make twelve short films, using three shots for every film. They’ll all be silent and wordless except for the title Opening Series, which is a reference to Olsen’s “open form” and free association. It can’t be pinned down as a static work of art or exhibited as my new film because it’s always changing. These twelve films range from a few seconds to three minutes, and each has a picture on the cover of its box. I’ve been making paintings and xeroxing them and putting them on the covers; these serve as the titles. To decide on the order of the films, you look at the pictures and choose. So the film has many possibilities of flow. Every screening is different because it’s connected to the person who picks the drawings, or sometimes the audience decides the order collectively. I was working on the paintings at the same time I was editing the films, so there’s an organic connection between the two. I keep track of the different screenings and what I get out of them, the relationships between the films. They’re images shot around the world. One begins with a wave cutting the screen diagonally and cuts to a bird sitting in remnants of old Egypt. The bird flies off and then there’s a half-second shot of the falcon god. Images in other films have more formal connections. And then there are more “personal” pictures, images of home…

MH: Will you put this film in distribution?

PH: Maybe after a while, but I want to stay with it at this point just to see how it’s working, because it all happens in connection with the people who make the choices. I need to see whether that works. I have a lot of fear in pinning down the films. I don’t have a drive to repeat what I’ve already learned.

Philip Hoffman Filmography

On The Pond 9 min b/w 1978

The Road Ended at the Beach 33 min 1983

Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion 6 min 1984

?O,Zoo! (The Making of a Fiction Film) 23 min 1986

passing through/torn formations 43 min 1988

river 15 min 1978-89

Kitchener-Berlin 34 min 1990

Opening Series 1 10 min silent 1992

Opening Series 2 7 min silent 1993

Opening Series 3 by Philip Hoffman and Gerry Shikatani 5 min b/w 1994

Technilogic Ordering 33 min 1994

Sweep by Philip Hoffman and Sammi van Ingen 32 min 1995

Chimera 15 min 1996

Originally published in: Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada, ed. Mike Hoolboom, 2nd edition; Coach House Press, 2001.

Duets: Hoffman in the 90s: an interview (2000)

Philip Hoffman: After finishing the autobiographical film cycle I wanted to play again. I brought a super-8 camera along with me to Banff in order to do some sketching. I began exposing a frame at a time while zooming, or moving the camera. The result was a Cubist kind of taking apart of the world. It splays the frame, making the image move. Because of its extreme speed, it is necessary to slow the image down afterwards, controlling the speed via re-photography on the optical printer. The lightness of the camera allowed me to play along with my subject in a musical way. This kind of shooting, or being in the world, marked the end of one kind of working, which was much more personal and traditionally ‘documentary.’

MH: Why was it important to break the space up?

PH: It was in the air. The Berlin Wall had fallen, film had become media, computers were everywhere and fragmentation ruled. The cycle of personal film work I’d finished allowed me to travel and show the work, and Chimera (15 minutes 1996) was the result. It was photographed in Banff, Finland, Russia, Egypt, England and Australia.

MH: Despite lensing for years all over the globe, your shooting style is very consistent.

PH: I felt electric. Like I was touching eternity. These camera gestures create rhythms at the speed of light following an inner-outer sympathy. I was doing a fair bit of inner work at that time—trancing, meditation, yoga—so what was coming to me in image was symbolically meaningful. I had my own narrative, no matter how abstract it might appear to others, but instead of people and places which are a part of a social world, it became another kind of journey. Chimera began in 1989 during the Banff residency and took seven years to shoot and edit.

MH: The shooting blends one place into another.

PH: It shows a world breaking down, and the images express the energy of change. The film doesn’t insist that market people in Cairo’s Khan Khalili and London’s Portabello are the same, but that they share an energy related to colour, shape and form. That’s why some of the film is abstract, to evoke these pleasures of sharing.

In Technilogic Ordering (1994), by contrast, the fragmentation is political, re-working media images of the Gulf War. The collisions mean more because lives are being lost, along with their representation. This sketch of Chimera is simply one way to experience the world. As a viewer you’re only moving forward, like the stream of images that come to us through TV, or the Web. Chimera is a representation of that way of being in the world. Gathering speed. But in the third and concluding part of Chimera I finally go back, and this return offers a critique of the first two sections where each image replaces and erases what’s gone before. In the final section a man plays electric piano in a Russian square, and this is intercut with scenes from a Finnish rave, and the great rock Uluru. Uluru is a sacred aboriginal site which I photographed from a distance. It stands boldly through it all. This movement finally brings us back to making pancakes in the kitchen, because despite virtual velocities and cyberspace, at the end of the day you have to go home and make supper.

I had a lot of trouble finishing the film, in finding the shape for these sketches. I finally returned to its original idea, which is contained in the title. Chimera is an animal in Greek mythology which combines the head of a lion, the body of a goat and the tail of a serpent. For the first time in my making, I didn’t have a narrative to hang the structure on, so I was guided by myth, and the beast’s embodiment of diversity and fragmentation. The first section begins with a roar on the soundtrack and proceeds with an accelerated drumbeat and a scream, which I associate with the roar of a lion. The second section has a very ethereal soundtrack, which is the goat on the mountain, ‘up in the clouds,’ where he finds his place. The final section is the serpent. It is filled with sibilant chanting which brings on transformation.

There were many things in my life that I pinned to these scenes. They are returning now in my making because I couldn’t deal with them at the time. I encountered three deaths while shooting this way. The deaths are not shown or even alluded to in these films, but they lie underneath each of them. Waiting.

Chimera‘s original super-8 footage was being blown up to 16mm by Carrick Saunders in Montreal. I gave him a call to see how it was going and his wife answered. There was some commotion—she left the phone and didn’t return. I phoned later that night and discovered he’d had a heart attack and passed away.

MH: He died while you were on the phone?

PH: Yes. And you don’t know why you’re part of it. Of course this is an awful tragedy for Carrick’s family, but I didn’t know him. As a witness to his death, I felt I was being given a gift, and that I had to do something with it. I just wrote it all down in my journal, but couldn’t figure on how it would become part of Chimera.

In the second instance, I was crossing a bridge over the Thames, just coming out of the Moving Image Museum where I’d shot their history of cinema exhibit. I was blurry eyed. I stepped out on the bridge where a stranger looked me in the face, got up on the bridge and jumped. I spied him through the cracks, already going underwater without a struggle. Dazed, I wondered if I should film him. And didn’t. A man came by and asked if he’d jumped. A woman arrived from the other side of the bridge and said she’d call the police. That’s when I came round. I’d been stuck in that existential moment where you see someone who wants to die. Do you let him? Should you do something? Can you? I ran to the other side of the bridge and met up with a policewoman who didn’t have a walkie talkie. I kept running until I found another cop who said they’d got him. A pleasure boat had come by and picked him up. What a coincidence, this man wants to die but a boat chances along. I asked the cop if he could let me know what happened, and that night I got a note: “The bloke who jumped in the creek is alright.” Both these events made me think about death, and how little control we finally have.

MH: Tell me about Technilogic Ordering (30 minutes 1994).

PH: The Persian Gulf War was a made-for-TV affair which filled me with anxiety. I watched the war with some of my students at Sheridan College where I was teaching. A couple of them—Heather Cook and Stephen Butson—began to collect images as a way of thinking about the broadcasts. It’s like when you have a lot of nervous energy you go for a skate. You have so much anxiety watching this stuff and you have no control over it.

During our gathering I found a VCR with a computer chip that fragmented the image into Muybridge-like box-frames. This machine allowed you to play the image, changing the size and number of the boxes onscreen—do you want 9, 400 or 1600?—and scroll them from left to right, like reading or media literacy.

We collaged some of the different footage we’d collected, inserting commercials, movie fragments and sports into news broadcasts of the war. Among other things, we wanted to show the difference between Canadian and American coverage. While many Canadian commentators questioned the necessity of the war, the Americans were blindly patriotic. As we discovered later, all the war footage had been cleared by the Pentagon, so it appeared bloodless and techno-centric. It was mayhem at a distance. The boxes were a visual way of commenting on the reports, making patterns out of this destruction, and allowing the pictures to critique themselves.

The montage featured many heavy-handed collisions. Kitchen cleaners were juxtaposed with images of the Iraqi army being ‘cleaned up.’ Airplanes from the Wizard of Oz smoked messages across the sky: “Surrender Dorothy.” There was a nationally televised football championship going on at the same time which blurred the line between sports and war. Both featured the same mass hysteria. Once the editing was done, the video footage was transferred to film because in order to really see television you have to look at it somewhere else, in a movie theatre for instance.

MH: Like much of your work in the nineties, this film began as a collaboration.

PH: After my personal work in the eighties it was time for the author to die. I wanted to relinquish control, explore ways of making that would expand the palette. In the early nineties I started three projects that had in common sketching, collaboration, and smaller format technologies (other than 16mm). With the help of Vesa Lehko and other friends in Finland Chimera was turned into an installation. Technilogic Ordering was made with Stephen Butson, Heather Cook and Marian McMahon, who naturally helped with all of them.

In Opening Series I collaborate with the audience by offering a film in parts, each in its own painted box. I ask them the audience to arrange the boxes in the order they would like to see them on screen. The film not only runs differently each time, but provides a picture of its audience. Opening Series arose out of questions of inter-activity, which too often means people watching computer screens instead of relating to one another.

Following Opening Series are three collaborations: Kokoro is for Heart with Gerry Shikatani, Sweep with Sammi van Ingen and Destroying Angel with Wayne Salazar. By the mid-90s, I’d committed to hard-core collaboration.

MH: Kokoro is for Heart (7 minutes 1999) has a feel of daily ritual and naming.

PH: I met Gerry Shikatani at Sheridan College where he worked in the writing department. Gerry’s a poet, a Nichols protegé. He writes sound poetry, novels, and food reviews for the dailies. One morning Gerry came up to the farm and we went for a drive, not thinking about making a film at all. We wound up at a gravel pit, and I pulled my camera out of the truck while Gerry interacted with the space of the pit, moving rocks and branches around. I shot two rolls of 16mm reversal. When I got the footage back I noticed the registration pin was slipping, so there were periodic stutters in the image. Trained as a cinematographer, I saw these as flaws, though Marian said they were like Gerry’s voiced poetry. He works with the structure and gestures of language, and the flipping frame reveals the structures of vision strained through the machine.

I optically printed the whole film one to one and two to one. So each picture had a double, one for each of its makers. Then I cut the film into twelve parts, and put them into twelve separate boxes for Opening Series 3 (7 minutes 1995). The audience would choose the order they’d be screened in. I made the paintings for the box covers by using natural materials like seeds and sunflowers, along with family photographs and paint. Then I put a blank canvas on top of the painted ones, laid them on the ground and drove over them with my truck, so every picture is doubled as well.

As an interactive work, the film began its life as part of the Opening Series experiment where the audience effected the order of the film by arranging the boxes. We also ran it as a performance at Cinecycle where Gerry sat in front of the projected image rapping out his sound poetry. Later, we fixed the order of the film, made a final print and renamed it Kokoro is for Heart. The performances served to find a satisfying, fixed order. But it can still run as an open ended work in the performance setting.

‘Kokoro’ is the Japanese word for heart, or life force. Here, it’s the heart of the land, speech or breath. Gerry is shown as part of the landscape but separate from it, and his words on the soundtrack (a blend of Japanese, French and English), are a way of knowing or naming the land. They’re the language of the land or a landscape of language.

MH: Tell me about Sweep (30 minutes 1995).

PH: One of my interests in making the film was to go to Kapaskasing because that’s where my mother settled when she first came to Canada. My grandfather, Driououx, came to Canada to work as a lumberjack, eventually ran a poolhall and pushed moonshine on the side. The area they lived in was actually called Moonshine Creek. My grandmother, Babji, ran a rooming house. I asked my mother to recollect Babji’s stories for the film, which she does while looking at family photos. One of these shows the family gathered for Christmas dinner. Mom says this picture makes her feel happy, because at Christmas everything would go well. But I knew from my own growing up that visits to Babji and Driououx’s would always start in fun but often end with a plate of food hitting the kitchen wall. I pose these questions to my mother through narration, and her answer is evident in the grain of her voice. The violence and abuse in the household remains in her trembling speech. This is where our forgetting, and the things we care not to tell, come to reside.

This makes me think of Marian’s work, how the past lives in the present. The fears we don’t get over become part of our everyday life.

My mother’s image returns at the end of the film when I zoom in on her, followed by a zoom on me, as a reminder of that repressive pain, which flashes forward from the beginning of the film to its end, as suddenly and ferociously as the past takes over the present.

MH: Your collaborator is Sami van Ingen and his journey is also a personal one.

PH: Sami’s great grandfather was the American documentary filmmaker Robert Flaherty. He’d made ethnographic ‘classics’ like Nanook of the North, which was shot in Canada. While it is considered one of the first verité documentaries, most of the scenes were staged and rehearsed. And it offered a particularly white view on native practices, made in a time when white meant ‘objective.’ Sami wanted to return to some of the places that his grandfather had been in order to deal with this part of his family’s history.

While we were making the film, a feature-length drama was released about Robert Flaherty, which reveals a love affair he had with a native woman. Everything was suddenly out in the open. Sami and his family already knew this, but no one dared to speak about it. They were keepers of the legend, the great genius, the family name. Our film begins with a suggestion that we will hear details of family history, but Sami didn’t want to go further in that direction, so the film arrives at more general conclusions. We used archival home movies showing white men’s journeys to appropriate the north. Sami’s great-grandfather, Robert Flaherty, was just the most famous person who went up there. So while we couldn’t speak of the family legacy, we could show white men hanging around the native camps, and the effects they had. These scenes are intercut with shots of Sami and I dozing around a pool on our way home amidst spring blooms, implicating us as part of another wave of white explorers. The film has a strong visual thesis, but parts are missing. It’s like the deaths I encountered while making Chimera, real life overwhelmed its representation.

MH: The film shows the two of you traveling north by car, meeting people along the way, and entering a Cree reservation. This journey ends when one of the native guides takes you across the water to Fort George.

PH: Fort George was one of a series of British forts built in the North, and Flaherty would have traveled through there. The Fort is gone, but we found an old Hudson Bay Company trading post still standing which we filmed. I say in voice-over, “You’re not going to find your grandfather here. It’s gone now. It’s over.” Around the building we discovered a lot of beautiful driftwood. Earlier in the film we showed the dam, and talked about how the need for hydro-electric power overwhelmed Native protests, and how their burial grounds were flooded because the dam raised the water level. This driftwood is also a result of the dam. These are the bones of the forest, the ruined culture. The driftwood was shot in high contrast stock, with the haunting call of Canada geese in the distance. Then we have a lunch of canned fish and tomatoes which we film, because all we can do now is film ourselves. We’ve come all this way to shoot the making of a sandwich.

During the trip all of the native people we met asked us to film them. During the dam protests so many white journalists had been up to visit they were used to it. They’d even built a motel just for visiting politicians, and had a huge teepee as the local supermarket! We always refused, saying we don’t want to tell your story, this is up to you, and it always has been. So the film’s critique of ethnographic filmmaking shows the failure of white culture to integrate, proposing a movement alongside instead of the usual pictures of control.

At the end of the film, during dinner, I showed our native host Christopher Herodier how to use the camera, and he shoots us eating. I left him with the camera, saying, “Give me a surprise.” When we got back to the city and processed the roll we discovered that Christopher had filmed a teepee against a backdrop of new housing, and then the two of us against a sunset, slightly out of focus.

When the film was finished, Petra Chevrier invited Sweep to screen at the YYZ Gallery. I called Christopher and asked if we could show our work together. He had made a videotape called Chiwaanaatihtaau Chitischiinuu (Let’s go back to our land). It shows a Cree protest against the building of another dam, the canoe voyage from Fort George to Great Whale, the singing and the outrage. The two pieces played together for a month and it was very satisfying. It reflects our approach of living cinema.

MH: Can you tell me about the title Sweep.

PH: To shoot the drive northwards we rented a motor that ran the camera very fast, giving us super-slow motion. At the head of the shot the motor’s still gaining speed, so you get a fast motion which is overexposed, which then turns into slow motion at a regular exposure. This gives a sweeping motion to the image, a sweeping of landscape and driving. ‘Sweep’ is also sweeping the road clean, trying to start over again, sweeping away Flaherty.

MH: Destroying Angel (32 minutes 1998) features another collaboration, how did that begin?

PH: I met Wayne Salazar in Australia in 1991 at the Sydney Festival. The curator Paul Byrnes had invited me show all my work. In Sydney, Paul would take you to supper every night, with a small group of filmmakers and curators, and Wayne was party to that. It was a marvelous time. Soon after the festival I visited Wayne in New York, and a while later he called to tell me he’d contracted AIDS and was very sick. He was going to tell his mother who lived in New York State, so I invited him to come up to the farm and relax and meet Marian. That’s when we started shooting. I don’t know how these things start. Maybe it’s just that you’re always shooting film, and when people come you keep shooting and then films start.

The farm reminded Wayne of his rural youth, the day trips he used to take with his father who worked as an insurance salesman. Wayne’s bad health made him wonder how long he was going to be around, and he felt compelled to deal with his father who had abused him as a child. They hadn’t seen each other for years, but Wayne decided to go see his father and tell him he had AIDS. This all became part of the film. The first weekend he came he got along well with Marian, and they spoke about personal histories, and her themes of remembering and forgetting. He was very sick then, and taking a lot of pills. The drug cocktail hadn’t been introduced yet, so he was tired and depressed. It was Wayne’s idea to make the film and I felt my role was to assist. He’d made a short video about Cuban artists, had seen a lot of films as a curator and had been painting since art school, but really had no experience making personal film work. Which is fucking hard. During the making, I felt I was back working on Road Ended because the struggles were the same. Road Ended took seven years to make, trying to give shape to these concrete bits of memory, working without a script, and letting the camera respond to experience as it’s happening. I stayed patient, trying to help give Wayne an outlet. I learned more about his struggles of growing up gay, dealing with his macho father’s disappointments, and how he and his lover Mickey were finding a way to live.

It began as a film about our fathers, but it quickly became clear that mine was no match for his. The stories of Wayne’s abuse created too much of a contrast to my father’s sympathetic parenting. I shot sequences and told stories which were part of an early cut, which might one day join another film. But there was so much anger and need on Wayne’s part that I had to withdraw. The decision was made when my partner of twelve years, Marian McMahon, was diagnosed with cancer, and a week later, during a biopsy, she died. We stopped making the film, and when I climbed up out of the hole, that’s when I moved my voice out of the film. I needed to make my own film about Marian, her life and the grieving. Marian was already part of Destroying Angel, asking Wayne questions on video about his meds, and AIDS, and everyday life. Wayne felt close to her and asked if her story could be developed more in the film, if we could show this passing, and I felt that would be right.

MH: You show Wayne and Mickey getting married.

PH: Back in San Francisco, Wayne got healthier, which was partly the drugs, diet and exercise. But the film had a lot to do with it as well. Wayne and his partner Mickey decided to get married. Mickey is Austrian, so an Austrian TV crew arrived to shoot them for a news program on San Francisco gay life and marriage. And I thought, yes, we have to have this in the film. Their reportage was typically television. It opens with a shot of the Golden Gate Bridge, then moves into the gay bars, and sexual activity and dancing and high pitched screaming, but in our film, we inserted a shot of Wayne and Mickey walking down the street buying flowers. Very everyday. It’s a nice moment because it shows how television creates stereotypes.

MH: Why did they want to get married?

PH: They were in love of course. But I think it was a political decision as well. In a culture that doesn’t accept their sexuality, it was a step towards gaining the same rights as heterosexual couples.

MH: Wayne speaks to his father surrounded in darkness, directly to the camera, outlining a history of ignorance and abuse. But when we meet his father at the wedding he looks so benign.

PH: The film reveals how the monsters of our past live in us. He’s become an old man, no longer shouting abuse at Wayne. But it doesn’t change what he did. He hurt Wayne, and neither of them could deal with it. They held onto this pain for years. At the ceremony, Wayne says it hasn’t always been easy with his father, who then breaks in and proposes a toast to Wayne and Mickey. He says that he’s from Guatemala, a culture where gay people exist only in the closet. And then he wishes Wayne and Mickey happiness in their life together. But it took the making of our film to release this fear. It’s Wayne that’s done the work to recover his past, and the evidence of this work is Destroying Angel. While the early passages of the film are drawn from Wayne’s point of view, the ceremony at the end is shot in a verité style by the Austrian video crew. Finally, we’re seeing something outside of Wayne’s frame. He’s no longer telling his story using voice-over. We enter another side of him, and this adds in a profound way to the information we get about his relationships.

Wayne called me last week, a year after his father died. He said, ‘I don’t recognize that guy in the film.’ He was referring to himself. People use different tools to create change in their lives. Some use work, or alcohol, or art. Wayne doesn’t need to talk about his father that way anymore. This is a familiar feeling for me. passing through, for instance, was a grieving for my grandmother Babji. You hope these rituals of filmmaking resonate for others.

Marian’s death is revealed in Destroying Angel and people say, ‘you must find that hard to watch,’ but I don’t. I love her images, her voice and her writing. After Marian’s death, while looking up references to bring her Ph.D. thesis to completion, I dwelt for hours on the small hand-scribbled writings she left on the texts she was reading. No matter how esoteric or academic the text, her response would always tune in the personal, the everyday. She came back to life for me through her writing. The film I’m working on now attempts to deal with the traces she’s left behind, so that I might better understand our time together and learn something about death and life. The dead carry on longer than the living, and it seems that the force of a life lived is stronger once it ceases to exert itself… its silence and mystery.

MH: The title Destroying Angel suggests an angel that returns to wreak vengeance, a once purity that’s now armed.

PH: It’s also a mushroom, one of the most deadly and poisonous. The poison is the virus, which brings pain and suffering, but also transformation and change and growth. There’s an eating sequence in the film shot up at the farm where Wayne is making us dinner. In the early nineties there was still such a fear of casual infection, you know, he could cut himself and infect us, but instead there’s only celebration. We’re living right now, the camera’s floating around the food and we’re having a ball in the face of it all.

MH: Much of your work in the 90s is more hermetic and difficult than your autobiographical cycle. What would you say to those who feel your work, along with others in this small field, is willfully self enclosed, unnecessarily obscure, interested in formal issues in a medium which itself is coming to an end, and on the other hand suffers from solipsism and narcissism.

PH: Yes and? It lives with me and that’s what is important. Often circumstances collect around you and you have to make the film as well as you can without knowing why until later. Sometimes you get a song out of it, sometimes a mumble.

MH: Is it important to finish work or is it just the process that’s important?

PH: I need to bring everything to some kind of completion. I learned from my dad how to start and finish things in the factory when I used to make boxes every day. Screening your work and receiving feedback is an important part of the process. We experimentalists may not get the TV audience but that’s alright. Our work has a different purpose. We’re the people behind the stage sweeping up the old act and getting it ready for the new show.

People who try and push boundaries are part of a lineage that’s a much thinner thread than CNN or Cineplex, but it’s continuous, it’s a living history. We’re carrying this on, and maybe I’ll make just one film that’s important, that will have an effect on people. I hope I haven’t made it already. If I’ve always held on to the personal it’s because I believe that what I’ve lived has a shape, an organic world that can be shared, through film, with others.

Originally published in: Landscape with Shipwreck, ed. Hoolboom/Sandlos, 2001.

Passing Through: The film cycle of Philip Hoffman (1993)

The films of Philip Hoffman have revived the travelogue, long the preserve of tourism officials anxious to convert geography into currency. Hoffman’s passages are too deeply felt, too troubled in their remembrance, and too radical in their rethinking of the Canadian documentary tradition to quicken the pulse of an audience given to starlight. He has moved from his first college-produced short, On the Pond (1978) — set between the filmmaker’s familial home and his newfound residence at college — to a trek across Canada in The Road Ended at the Beach (1983). In Mexico he made the haiku-inspired short Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion (1984). The next year he was invited to Amsterdam to observe the set of Greenaway’s A Zed and Two Noughts, and made ?O,Zoo! (The Making of a Fiction Film) (1986). Trips to Europe to unearth the roots of his family formed the basis for passing through/torn formation‘s (1988) pan-continental dialogue of madness and memory. Kitchener-Berlin (1990) takes up this immigrant connection from his father’s side of the family. And the last work, in what was only named afterwards as a cycle, a revolving peer of understanding, is river (1978-89), which is both a return home, and an acknowledgment of the restless flux which lies at the heart of this project. For all of their circumnavigations, this cycle is primarily concerned with pictures of home and family, gathered with a keen diarist’s eye which has revamped its vision at every turn, shifting styles with every work, as if in answer to its subject. Denoting the family as source and stage of inspiration, Hoffman’s gracious archeology mines a concession of tragic encounters, powerfully refashioning his intersection with the limits of representation. His restless navigations are invariably followed by months of tortuous editing as history is strained through its own image, recalling Derrida’s dictum that everything begins with reproduction. Hoffman’s delicately enacted shaping of his own past is at once poetry, pastiche, and proclamation, a resounding affirmation of all that is well with independent cinema today.

On the Pond (9 min b/w 1978) is an elaboration of the family slide show, its intimate portraits greeted with squeals of recognition and a generational shudder of light and shadow. The slides show the filmmaker as a child, his unguarded expression an ensign for innocence. In winter he is dwarfed by the furry excess of his parka, summertime finds him casting flies on the Saugeen River (subject of the final film in this cycle), trekking through forest, or lounging by the family cottage. Reviewing the photographs with family, the filmmaker asks, “What do I look like?” in a gesture that underlines the reliance of identity on the family’s complex of role play, fantasy, and projection, on its investment in shared secrets, and its dramatic restagings of generational loss and symmetrical neglects. As the author of the film, Hoffman assumes a distinctly paternal guise, but within its confines he is very much the son, waiting on his elders for the signs of assent that will take shape as his own desire. Hoffman offers up these photographs as evidence, insistently returning to moments whose nostalgic impress provides a blank for the interchange of codes and riddles. These are hieroglyphs from the dead world, resurrected in order to reconstruct the memory of a time alien even to its inhabitants, because the measure of this familial solidarity must rely on a willful disavowal of experience, casting aside the ghosts of illness and psychosis, turning away from all that fails to conform to the familial ideal. What lies unspoken here, though hinted at in Hoffman’s careful editing, are stories of a darker nature, his mother’s illness, the death of relatives and the traumas of dislocation.

These photographs are drawn in a dialectic with dramatic re-enactments of Hoffman’s boyhood. These centre on a boy of seven skating “on the pond,” his only company a German shepherd. As he diligently hones his puck handling skills, his easy skate over the big ice is interrupted by intrusive voice-overs — the exhortations of a coach and the scream of hockey parents. As Hoffman pans over a well stocked trophy case and the young boy falls to the ice in a paroxysm of push-ups, the public stakes of this private practice become clear. He is leaving the family. His play has already become a kind of work, the means by which he will move from the pond to the city, though the cost is the incessant clamour for achievement. Everywhere the superego beckons.

No soon has the dream has been conjured then it ends. In a long pan over a projector run out of film and a record player at the end of its disk, the filmmaker rises from his bedside vigil over the past to close the apparatus of memory. Confronted with the escalating tensions of his trade, and a growing distance from his cherished solitude on the pond, Hoffman quits hockey, turning instead to a diaristic filmmaking which will stage the self in its various incarnations. All this is suggested in the film’s closing shot, which shows Hoffman join his young double, confidently calling for the puck before slipping on the icy sheen, no longer the player he once was. Brilliantly photographed in black-and-white, with a spare piano score and a sure use of accompanying sound, On the Pond marked an auspicious debut from Canada’s premier diarist.

The Road Ended at the Beach (33 min 1983) is a shaggy road flick whose way stations of memory allow past adventures to meld into present ones, though its true aim is neither adventure nor destination, but an examination of male myth. Setting off for Canada’s east coast, Hoffman joins two friends, fellow filmmaker Richard Kerr, enlisted as sound recordist, and Jim McMurry, driver of the van. Road’s opening sequence finds them bent over the van, painting over its psychedelic glyphs with a fluorescent orange. Each of the “characters” is introduced through flashback — McMurry as the manic, fast-talking, blues-singing driver of past trips, Kerr as a fishing pal and filmmaking companion. In Ottawa they meet up with Mark, a friend who used to play jazz trumpet but now blows in a military band. “There’s things you do for love and there’s things you do for money,” he flatly intones as the travelers move on, meeting Conrad Dubé, a cyclist since 1953, who has crossed the globe eight times, barely able to speak due to infantile paralysis. In Sable River they find Dan, a friend from film school now working in the east coast fisheries, trapped in a dead-end job in order to support his family. They push on to Cape Breton where they find Robert Frank, avatar of Beat romance and adventure, the irascible photographer whose book The Americans undraped a mythic travelogue of naked encounters. But he appears before them on a distinctly human scale, and they stand together as four strangers feebly attempting to speak, their visit inspired by nostalgia over a time they never had. Frank’s visit marks the end of Road‘s first movement.

Road’s second movement opens with the remark, “Now I look inside the van.” Once again each of the three characters is introduced — the filmmaker lost in a reverie of Kerouac adventures, McMurry obsessed with the wretched condition of the van, and Kerr feeling imprisoned. Hoffman notes, “I expected adventure, but somehow the road had died since the first trip west,” a summary assessment of old ties which have vanished even before the trip’s begun. Today their cross-country dash serves only as a reminder of their differences, the passing of youth, and the end of an exclusively male fraternity. The third movement, entitled The Road Ended at the Beach, features a reprise of the film’s encounters and Frank’s weary responses to questions about his Beat relations of two decades before. “Maybe it was freer because you know less. I never kept in close contact with them. Sometimes I see Allen…” These offerings mark an eerie prophecy for the three travelers, whose time of abandoned locomotion is past. The din of the road can no longer disguise the fact that they never learned to speak with one another. The film ends with the promise of its title: children and dogs move back and forth across the beach as a massive rocky outcropping peers out of the waters in the distance. These planes of play, passage, and foreboding are a metaphor for the film’s journey. Road is a passage from innocence to experience, cast beneath the paternal backdrop of a Beat mythos, its romantic notions of flight decomposed in the cold frame of the van.