Notes on a photograph in Richard Fung’s Sea in the Blood

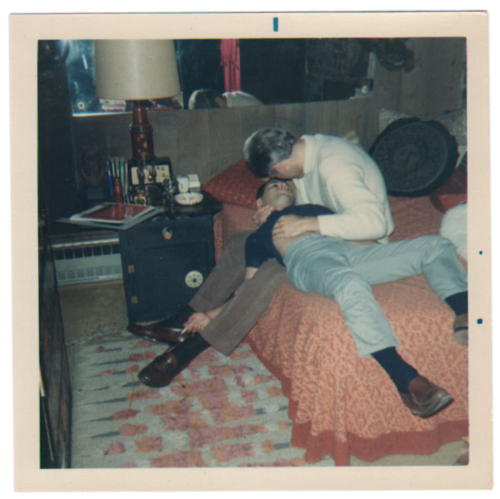

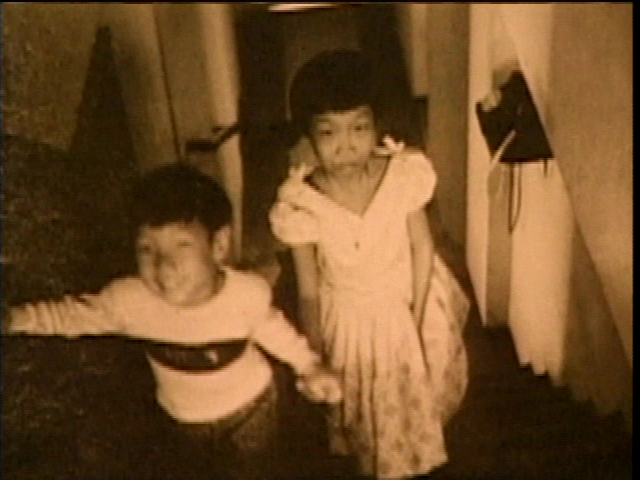

They are walking up the stairs together. Ascending. Or are they posed there? Forced to wait while the photographer applies to this moment a frame which will absolve them of the need to remember. Instead of walking: automobiles. Instead of witnessing: the television. In place of memory: the photograph.

Richard is already looking into the camera, towards home, his face a blur of concentration, some part of him already understanding that he will be more comfortable behind the camera than in front of it. But in his years as an artist, he has not held the camera up like a shield, he has insisted all along, as he insists here, on his own visibility, his own mortification.

Besides Richard his sister Nan. She is six years his senior, the responsible one, so even though she trails behind him, she leads him nonetheless. Tempering the rush. Measuring the cost of arrival.

Just prior to this photograph, Richard dishes a little history, the setting of this picture. Excerpts from an educational film describe Thalassaemia, a Greek term which lends this videotape its title: Sea in the Blood. A baritone voice of science explains that it’s a hereditary anemia, a kind of leukemia. Passed along bloodlines, this illness is a way for unmet generations to commune, remaking bodies as the stage for an ancient way of knowing. This communication, this illness, is also a kind of memory, the first memory perhaps, of the way we have to die.

There is something in Nan’s dress that makes her appear older than she really is. Is it the puffed crinoline shoulders, the long sweep of fabric gathered in a train behind her? Or the pair of blank stays that hover at her back, the beginning of wings? Like Richard, she is pitched towards the future, though she’s in no hurry to arrive. She knows only too well what waits for her at the top of the stairs, and this knowing has made her face serious. She is already a woman, though not yet a teenager.

Richard belongs in this picture, even as he moves to escape it. He is already reaching for the man who will one day hold this photograph in his own hands, the man Richard, wondering that he used to. That he could have once. For the boy, Richard, memory is still in his future, along with the understanding that each of our desires exacts a toll. His sister Nan knows this better than anyone, her childhood is over, and it’s been over for a long time now. In its place, she takes hold of her brother’s hand, this ghost in her too-tall dress, this old woman of ten. Richard must be young, stay young, for the two of them. Her childhood ended when she learned of her illness, the sea in her blood. Along with her brother, her Richard, the one who always smiles, she is trying to hold on, welcoming death the only way she knows how. Slowly. By degrees.

In his videotape Richard says, “Nan’s eventual death was a fact I was born into, like mangoes in July…” The illness is there from the beginning, at Nan’s birth, inseparable from her. She is the disease. Not a temporary shelter, or a way station, she will never know the other side, the blank horizon of intimacies not yet tasted, desires shared with strangers. In their place she adventures with her younger brother, in their early years tracking comets and trying on jewelry, and later, as conspiratorial confidantes, reading Mao’s red book which she keeps hidden from their father.

In the photograph her right hand clutches her brother while her left is withdrawn, lost in the folds of her dress. Her left hand holds her secret, the thing she cannot say, and cannot show, not even here, on the steps of this shared oblivion.

She is the still centre of this family, the keeper of its mystery. Years later, she will be the first person Richard comes out to. Richard is the confessor, the one who has returned to tell the how much and why and what of it all, to race up the stairs and take the camera in his own hands. He is too late, and too old now, to be able to cheat death, but he can tell its story, and he tells it here, in this moment which shows two children on a stairwell, ascending.

Originally published as: “Stairs” in “Like Mangoes in July: The Work of Richard Fung ed. Helen Lee and Kerri Sakamoto (Toronto: Insomniac Press, 2002)

Thinking Pictures: an interview with Richard Fung

When he tells me the story of how he got his start in fringe media I have to sit back in my chair for a moment. Wait, wait. There was a time when Richard wasn’t making videos? It’s hard for me to grasp exactly, just as it’s hard to imagine what the Canadian media art scene would look like if it had not grown up with Richard’s accompanying text missiles which have blown apart commonly held wisdoms again and again. His justly anthologized Looking for My Penis: The Eroticized Asian in Gay Video Porn took on stereotypes of gay desire. His Programming the Public missive looks at the way queer fests help shape the identity of its audience (who is looking in the mirror now?) It begins with this line: “Whenever I go to a gay bathhouse, I’m struck by the ordinariness of so many of the men, who seem to evade all recognizable gay styles of masculinity and femininity…”

One things is for sure: Richard always knows how to lead, though his characteristic modesty keeps him from standing at the front of the theatre and hectoring us with his keen intelligence. For twenty years he has reworked the documentary, leavening it with personal insights, bringing his camera inside the home, settling it beside his mother, then his father, and most memorably, his sister Nan. In his brilliant summary work Sea in the Blood (2000) he lays down a duet of his sister’s fatal illness and his own lifelong romance with Tim, an AIDS activist with an illness of his own to contend with. The personal is always and necessarily political in these mosaic recountings which never shirk from the task of unsettling received wisdoms. How warming to imagine that we live in a post-identity culture, that we’re all just getting along, that the glass ceilings and racial profilings and hate crimes are relics of a bygone time. And how much rarer, and how much more urgent, is the need to continue to point out the inequities which continue to exist in a North American art world which is primarily white (from consumers to producers), and where power brokers in the off off off off Broadway world of fringe productions are still similarly monochrome. Richard’s work (as teacher, mentor, programmer, artist, writer) stands in the face of this backwards tide, quietly persistent, bristling with intelligence, raveling out the effects of global empires in local details.

MH: Pictures from your childhood have appeared occasionally in your work, which leads me to wonder if there are early encounters with picture making that were ‘formative.’ It is by now a commonplace to state that pictures take the place of memory, but are there memories which continue to follow you around—and are these memories pictures most of all? Or is it a smell, the touch of someone, which insistently recurs? Sometimes my memory dreams are nothing but text scrolls, elaborate title sequences which admonish the guilty (moi), offering remedies and reflexive treatments (KEEP READING!! NEVER STOP READING ME!!) as if the future/past existed only as a book. Do you feel that your work, which spools out the same ordered picture sequence again and again, is not an image of memory but of time travel?

RF: I grew up in Trinidad. As the youngest child in the family, by the time I hit puberty all of my siblings except one had moved away to study. My mother was the second youngest in her family so I never knew my grandparents or any of their generation. And my father, having emigrated alone from China, had no close relatives around. So from very early on, photographs were these little bridges across time and distance. There were the tiny sepia prints of my grandparents and the great aunts I heard stories about; the photo of my father’s fortress-like house in China; the images of the siblings who had died before my birth, three by that time; later, there were the snapshots and graduation portraits my brothers and sisters sent home from Ireland and Canada. Photographs were about death or absence. As I grew up photographs also came to represent holidays and special occasions. These were different, always in colour.

Regarding the apparatus, Brownie is the word I recall first hearing, but I don’t have a strong image of the camera. I think it was the colour of milk chocolate, but then I’m also getting a flash of yellow which makes me wonder if I’m not thinking of my teddy bear. In my teenage years my sister and I shared a Kodak Instamatic, where little cartridges replaced spools of film—very modern. I took many pictures with this camera. In my last years at home I did a series with my sister Nan as model and me as fashion photographer. She struck Twiggy poses and I shot in canted angles. Whether it was the Instamatic or the home movie camera my mother used, the film always had to be sent to America for processing, so the photographic image necessarily carried the glamour of “away.”

Funny you should mention the feeling of being implicated by the photograph. Here is a story I don’t think I’ve ever told. From the time I was really young I used to like to dress up. My sister and I used to raid my mother’s closet, she picking the lock. We would find things like my grandmother’s jewelry, my mother’s dressy dresses (she had a whole funeral collection in black, white and violet, the Trinidadian mourning colours), my cousin’s wedding dress. We tried them all. In my teenaged years, I remember finding a black and white picture of me dressed in one of my older sister’s dresses, sitting on the floor with the wide skirt spread out around me in the classic pose of the late 50s. I was mortified and I think I destroyed it. I looked for it years later and was relieved not to find it in the family album. I assumed that the empty rectangles on the pages marked off by the little gold sticky corners indicated the success of my censorship. Now I’m not so sure the photo was actually destroyed and perhaps one of my siblings or someone else has it. It’s so long ago that I’m wondering if that photo and its demise wasn’t an anxious fantasy in the first place. So, yes, photography also contained the threat of evidence that could be used against me.

As for dreams, they are primarily visual. They are almost always set in the childhood house I left for good thirty-five years ago, which has been sold and completely remodeled. The atmosphere is always tropical and I don’t think I have ever dreamt of snow. I don’t recall smells in my dreams, nor text.

MH: Did you feel that motion pictures were waiting for you, all along, to pick up a camera and begin? I wonder what kind of movies you grew up with in Trinidad? Did they sow the seeds of what was to come, or does your practice emerge from a place completely removed from the burnished starlight of the big screen or the melodramas of the small one?

RF: I grew up on Hollywood films served up in art deco confections around Port of Spain. The theatres had names like Deluxe, Globe and Roxy, and were divided into balcony (the most expensive), house (where we sat mostly), and pit (the cheapest section, just in front of the screen). People spoke back to the movies then, especially from the pit, shouting advice to the “star boy” and “star girl,” or making witty commentary, so much so that at times you couldn’t hear what the actors were saying.

Movies were not an obsession, but an enjoyable treat, like hamburgers—they were things I did with my sister and her friends. My parents rarely went to the cinema, and my mother didn’t approve of snack food. As a child I watched cowboy and Indian movies and war films. Later I marveled over Mary Poppins and The Sound of Music, and could sing all the songs from both. At twelve the catechism class at my Catholic high school went to see The Greatest Story Ever Told. At fourteen the English class went to see Franco Zefirelli’s Romeo and Juliet and I couldn’t take my eyes off the cod pieces. Now as I’m thinking about it, I also remember nights at the drive-in watching movies like Blue Hawaii with Elvis and the beach party series with Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello. And how could I forget Shirley McLaine in What a Way to Go!? I loved the glamour of that movie. I think the last film I saw in Trinidad was Dr. Zhivago.

Then I went away to finish high school in Ireland and started thinking of myself as grown up. With this hip new identity, movies seemed frivolous—until I saw Claire’s Knee by Eric Rohmer. That film put me into a delicious, rapturous yearning for weeks, so much so that I haven’t dared see it since. (I had a similar reaction to Brokeback Mountain). In Ireland I also saw The Ruling Class with Peter O’Toole and I began to see that cinema could make you think. When I came to Toronto I happened in on a double bill of Women in Love and Sunday Bloody Sunday. I had a huge crush on Alan Bates and the male kiss in Sunday Bloody Sunday came as a complete shock; I thought it was going to be a war movie. But it was during Andy Warhol’s Lonesome Cowboys at Cinecity, the now defunct rep cinema on Yonge Street, that I held hands with the straight guy I was in love with. Afterwards we made love for the first and only time.

With all this cinema in my life I still never thought of taking up a movie camera, and when I entered art school it was to study industrial design. Later I majored in cinema studies at university, but it was only by chance that coming out of art school I got a job at a community TV station. My advisor at OCA, the journalist Morris Wolfe, was extremely supportive, and after I graduated he set up an interview with the editor of Saturday Night magazine. I was so out of it I had no idea what I might do there, so it was an awkward meeting. If I’d been more sure of myself perhaps I could have ended up as a journalist. Instead, I auditioned for a community TV animator job in Lawrence Heights, and that’s how I learned to make video.

MH: Godard has often stated that watching a movie, writing about it or making one are the same for him, that the cinema is an extension of critical faculties. As someone who is constantly on the road delivering state of the cinema addresses, do you feel the same?

RF: I do occasionally give talks, but the topics are much more defined and modest than “The State of Cinema.” I was reminded of the dangers of such a project just last night at the Toronto International Film Festival, when I saw The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema by Sophie Fiennes, a three-part documentary featuring Slavoj Zizek. Over the course of two and a half hours, the philosopher and psychoanalyst reads specific films and ponders the meaning of cinema in general. Zizek has an uncanny and fascinating screen presence, and Fiennes employs a clever device of seemingly dropping him into the films he is talking about, using recreated sets and intercutting. However, I found myself in equal parts seduced and distanced from the interpretations as I began to conduct my own meta-analysis about Zizek’s discourse, which is unselfconsciously asocial, apolitical and Eurocentric, even as he universalizes subjectivity and sexuality. His selection consisted of Hollywood movies, not surprisingly heavy on Hitchcock and Lynch, with a nod here or there to a handful of European directors: Bergman, Tarkovsky, Eisenstein. There were, as far as I remember, no Asian, Latin American or African films discussed. Yet he talks about how “we” think, and how “we” invest in “cinema.” At the start he shows a clip from an American film whose name slips me. In the scene a train cuts across the path of a woman walking down a street. As she waits for it to pass, she looks into the windows of the train which show first a couple of black cooks, a black bartender, a black maid ironing, then a white woman dressing, the silhouette of a man shaving, then an elegantly dressed white couple in a spacious compartment, and finally a well-dressed white man with a martini. My memory may deceive me, but this is how I remember it unfolding. In talking about the scene, Zizek entirely overlooks the astounding display of racialized class structure. This film underlines for me the limitations of close reading as a strategy for understanding films.

Now as for Godard’s provocation, he is obviously talking about his own engagement with thinking through cinema, which he does as a viewer, critic and maker. He incorporates and implements in his films and videos observations and analysis, as few others are able to do. I have a dual practice as a writer and a maker, and I watch a lot of work—though it does involve a degree of hubris talking about what I do in the same paragraph as Godard. It seems to me, however, that the phenomenological dimension of a film or video—single-channel, installation or on the web—is quite distinct from that of text on a page. So even though they involve a critical faculty, I couldn’t say that the activities of writing and making videos, far less viewing, are the same for me. There are some videos of mine that have a kind of “tightness,” closer to that of a written essay—Dirty Laundry, for example. Nevertheless, even here there are purely audio-visual metaphors whose presence hit at an altogether different register than the dry reasoning of writing allows. One cannot control the interpretation of the timbre of voice, the personal resonance of a soundscape, the idiosyncratic associations of colour. This holds true for even the most conventional documentary. Think what it would be like if laws were not written with black ink on paper, but held as videos or films, voiced and imaged.

MH: In My Mother’s Place (49 minutes 1990) you don’t deliver your mother to us right away, the voice-over states that you wanted to show a picture of her emerging on a snowy morning from her suburban house, but because the weather was uncooperative you shot the scene later, sans mother. And before she appears as a speaking subject you show a succession of women who narrate questions of representation: what to frame and why. Why this deferral and delay of your mother-and why did you choose to frame her through women closer to your life than to her own?

RF: I knew that my mother could be easily consumed as a classic ethnographic subject, a native informant. Though not so in a cosmopolitan city like Toronto, in many places people find the combination of Chinese and Trinidadian heritages surprising. By deferring her appearance, I wanted to foreground these issues and the stakes of representation to create a more critical and self-aware context before you actually see her.

Regarding the other women, I wanted to situate her story in a broader historical and global context, but I didn’t want experts interpreting her story. I wanted to juxtapose these other stories so they would sit next to hers. That was the strategy.

MH: Why did you decide to begin this project?

RF: There were two reasons. I began making independent video by accident. It’s partly John Greyson’s fault. After returning from living in New York, he offered me the use of his camera and his services as cameraman. What we shot became Orientations: Lesbian and Gay Asians (56 minutes 1985). It was my first independent production. I didn’t expect it to go anywhere but it was programmed at the Flaherty Seminar and the Grierson Seminar, and all of a sudden I was a video artist. In the mid-1980s there was growing interest in a politics of identity, gay/lesbian imagery and questions of sexuality and my work was taken up in a surprising way. My second video, Chinese Characters (21 minutes 1986), was an examination of gay Asian porn, and owed its circulation to Colin Campbell, Gary Kibbins and John. I was increasingly situated as the gay-Chinese-Canadian filmmaker. There was a lot of interest, which was great, but I also became concerned about being trapped as a maker. There is a developed infrastructure of gay and lesbian audiences, festivals and critics. It’s very tempting to produce something suitable for this ready-made platform. But I began to feel the need to address my other interests.

I’d been long fascinated by my parents, and made a tape about my father who was born in China, but came to Trinidad at a young age. After my father died I finally went to his village in southern Guangdong in the fall of 1986 and made The Way To My Father’s Village (38 minutes 1988). This experimental documentary examines the way that children of immigrants relate to the land of their parents. It is about the construction of history and memory, the experience of colonialism, and about Westerners looking at China. I didn’t know China at all, but felt related to it in a passive sense, because others connected me with it. The tape is constructed of discrete segments, each representing different kinds of knowledge about China. Interspersed are different Western versions of China, from the quasi-historical account of Marco Polo to the organ of the Communist Party of Canada Marxist-Leninist. I situated my video as yet another Western description.

Then I made My Mother’s Place, a companion piece about my mother, which is about the dynamics of race and gender in Trinidad. As opposed to my feeling of distance from the supposed Chinese fatherland, this tape is about my roots in the Caribbean motherland.

My mother was born in 1909 and grew up in a village in one of the most remote places in that small country. I was interested in her consciousness as a British colonial subject, and my own formation as a child of independence, which came in 1962 when I was eight. The social and racial hierarchies my mother had been brought up with were already crumbling, in a formal sense, by the time I came of age. These hierarchies of race and class, though not so fixed or monolithic, persist today. The tape looks at the two of us; it’s about place, people’s place in society.

MH: The normative shaping modes of biography are absent in this tape. Instead we receive her scattered recountings, which speak of episodes but not stories. Was this resistance to “full disclosure” or even closure, a conscious strategy on your part?

RF: Definitely. I’ve done autobiographical work but it wasn’t until Sea in the Blood that I became interested in my own story as narrative. In My Mother’s Place I was interested in the relationship between colonialism and post-independence in Trinidad and Tobago. I was using my family to look at the way those changes played out in people’s lives. I was much less interested in an assessment of individuals for their own story. That’s why it functions differently than Sea in the Blood, which culminates in a confessional moment. And there were things that couldn’t be spoken of. My mother is part of a large family on a small island and the level of gossip is amazing. The tape says, “I’m not telling you the whole story. Details have been held back to protect the guilty.”

Family stories there have such large arcs, they’re all epics. If you look at the post-colonial literature that comes out of Canada, from writers like Shani Mootoo or Shyam Selvadurai, Rohinton Mistry or even Ann Marie MacDonald, you see epic family histories. When I first arrived here stories from the east coast felt familiar to me because they were filled with ghosts. I grew up in a place that was overwhelmed by supernatural figures, some of which are mentioned in the tape, like the soucouyant who sucks your blood at night. She flies though the air like a ball of fire and if you find her skin you have to put salt on it so she won’t be able to put it on again. In order to protect yourself you have to put rice in front of your house because she has to count the rice, and by the time she’s finished counting the sun will come up and she has to leave. I grew up in a place haunted by spirits. Even though I grew up in a middle-class suburb built in the 50s, most of our neighbours, the parents, that is, came from the country. It didn’t help that when they dug up the street to put in a sewer system they discovered a slave cemetery.

MH: It’s strange and wonderful to see home movies of you and your mother, which, as you tell us in voice-over, have more to do with the fantasy of your lives than its reality. Are home movies always staged? Who were these screen moments for? Were they an externalization of the same Good Housekeeping norms that led your mother to describe herself as a housewife on your school forms, even while she was busy managing a store?

RF: There may be moments where people sneak cameras and the subject is unaware, baby footage perhaps, but mostly home movies are staged moving picture albums. Trips, opening birthday presents, Christmas and sports events all stage the family. My mother would bring out the projector and we’d watch the movies as a family. It was never a production for others. It was about seeing ourselves.

Patricia R. Zimmermann, for one, has talked about the ways in which home movie technology occurred at the same time as the growth of suburbs and the nuclear family. Home movie instruction manuals constructed gender in a particular way. They insisted that the technology was so simple even a woman could use the camera. As a genre, home movies are about the growth of leisure time, celebrating freedom and the goods of capitalism. It isn’t about production but the benefits garnered from production. So our home movies never showed my mother at work, the workplace is what home movies were explicitly not about.

My mother suffered from an ongoing desire for legitimacy in class terms. She was raised poor, and worked with my father to pull themselves into the middle classes. But by way of context, her first cousins were absolutely wealthy and she came from the poor branch. She was very earthy and proud of it. She couldn’t abide pretension. On the other hand, there was a lot of pressure for her children to succeed, particularly through education. I’m the youngest by far and they had eased up by the time I came around. My parents made their money through an old fashioned style of business, putting in long hours at a grocery store, and my father had a farm. But he didn’t want that for us, which was quite different from the Chinese business milieu in the Caribbean where fathers expect their family to keep their business.

My mother, being third generation, came from a group of Chinese who were very westernized, creolized. Some had taken European last names and many of my mother’s cousins couldn’t use chopsticks.

On a school form my mother didn’t note her occupation as shopkeeper, but as a housewife. To construct herself as a housewife in 1960s Trinidad had a racial as well as class component, I think. White women might have described themselves as housewives. Similarly, we moved to a “residential” area when I was four. The quotation marks signify that the word is a new one, the idea that a neighborhood would be classed as residential was fresh and modern.

MH: Here’s my favourite line of the movie. “I look at her and I know who I am.” What a beautiful sentiment this is. But perhaps there is a shadow falling over this beauty as well?

RF: When I go back to Trinidad I feel like Spiderman, trapped in a web of social relations. When I was growing up I felt watched all the time. I felt that my place was fixed. After learning someone’s last name my mother could tell which part of the island their family was from and what their parents did. Social hierarchies were so stratified and clear-cut, it was difficult to move out of your class. Coming to Canada was liberating for me because in a city like Toronto you can create yourself and form fresh relationships. It’s a much more fluid society. When I had my first job my boss was from Northern Ireland. He was Catholic and his wife was Protestant, and he said they could never have married in Ireland. It was Canada that allowed them to do this. At the same time that fluidity could sometimes make me feel disconnected and alienated. But when I saw my mother I was very aware of my genealogy, my roots, that social web.

When I go back to Trinidad I am aware of the ways that my physical movement is subtly controlled, more so than in Toronto. Because I’m Chinese and middle-class I am unmarked in a suburban shopping mall, for instance. But in a working class context my presence stands out. For instance, if I go to the market people might call out to me as Chinese and I become self-aware of my difference in class and race terms.

MH: In Islands (8:45 minutes 2002) you reconvene John Huston’s Heaven Knows Mr. Allison (1956), which narrates the unfulfilled hopes of a marooned marine (Robert Mitchum) and an Irish nun (Deborah Kerr). The movie is set in the Pacific during World War Two, but is filmed in Tobago more than a decade later. As your uncle was one of the extras hired to play a Japanese soldier, you foreground his part in a series of overlaid titles which makes the background visible, and pushes the exertions of the film’s stars into the background. Why did you begin this project? What is National Sex? Did your Uncle Clive, your movie’s main character, often speak of his experiences during the Huston movie?

RF: Actually, two of my maternal uncles were extras in that film. It was part of the family mythology growing up, as well as a glamorous moment in the history of the islands. Fire Down Below (1957), directed by Robert Parrish and also starring Mitchum together with Rita Hayworth and Jack Lemmon, was shot in Trinidad around the same time. I imagine it had to do with the presence of the American bases during that period. I had long mulled over a larger project about my family’s enlistment as movie extras because they were Chinese in funny places—my brother was an extra in a Fu Manchu film when he was a university student in Ireland in the 1960s. But like many of my concepts the idea mulled too long. My uncle Cecil died in Trinidad, and later my uncle Clive in Toronto. I had helped care for Clive when he got sick and became fascinated by his life. Part of the narrative in Islands is the way that the awkward masculinity of the Mitchum character paralleled my uncle’s. He was a very manly man and his passion was hunting. He had his buddies, but to my knowledge and according to my mother he never had a romantic relationship—with either gender. He last worked on the offshore oilrigs in Trinidad and he had a car accident where I shot the blurry coconut trees that bookend the video. He stayed in a ditch overnight and was later put in traction for almost a year, but the hip had not been properly set, and after many operations he failed to heal. The real trigger for Islands, though, was the fact that the Huston film finally came out on video and I was able to see it for the first time. I found myself in the act of trying to recognize my uncles and the landscape of Tobago.

MH: When Huston’s film is finished your uncle sees it, though the filmed drama is undermined by the incongruity of animals appearing which have never been seen on the island, or nocturnal creatures appearing in daylight. Why were the islanders’ reactions important to include in your movie?

RF: Actually, the animals are typically Trinbagonian and shouldn’t be in the Pacific. This is a reference to the way that so many Hollywood films featured the sound of the kookaburra, an Australian bird, to signal the African jungle—in Tarzan films, for example. But as an aside, I actually misidentified the bird in Islands. I don’t think it is in fact a kookaburra, but something local that the sound recordist must have gathered. Interestingly, at a recent screening there was an Australian outside the theatre where Islands was playing and she said, “That’s an Australian bird.”

As for the cinema dynamics, in the Trinidad of my youth cinemagoers spoke back to the films, made comments on the plot or actors, gave them advice, created their own humorous dialogue. I wanted to show that people were not passive viewers but actively reinterpreting and subverting the text right there in the act of consumption. There is a particular strategy of resistance in Trinidad that manifests itself in a kaiso aesthetic, a way of re-presenting the world with a cutting, subversive wit.

MH: Islands ends with a tantalizing openness. Your closing two titles remark on the screening of Heaven Knows: “Uncle Clive sees the stars close-up for the first time. He strains to see himself.” What follows is a montage of blurry, rescanned crowd scenes filled with indistinguishable figures. Are these hazy pictures the best Hollywood can do?

RF: Thus far, I’m afraid. This montage is composed of all the scenes in the films featuring the Japanese soldier extras. There are many Hollywood films that I like, don’t get me wrong, but they are still subject to overwhelming systemic pressures. For instance, in order for a film to get production money in Hollywood, you need stars, usually American stars, and the characters they portray become the moral and emotional centre of the film, no matter where it is set. Whether the location of the story is the Caribbean, Africa or the South Pacific, whether the film is socially or politically astute, it almost always ends up being about the American and from an American perspective. Even when the film criticizes the Americans it’s still about them. How can it be otherwise? The solution is to have more films made in places like Trinidad—which by the way had its first feature at the Toronto Film Festival this year: Sistagod by Yao Ramesar—and to give them proper distribution. Just like we want for Canadian films.

In the last while, there have been a couple of films that suggest a new trend, that is, using African-American actors to play African protagonists in American and/or British features. Prime examples are Forest Whitaker as Idi Amin in The Last King of Scotland (2006) and Don Cheadle as Paul Rusesabagina in Hotel Rwanda (2004). Cheadle will also portray Haitian revolutionary leader Toussaint L’Ouverture in an upcoming production. In the context of Hollywood film and American race relations it’s a positive development that black actors can get head billing. It’s a long step ahead of white actors doing blackface in early cinema, or the longstanding practice in liberal films where racism or oppression is confronted by a white protagonist. An example would be Cry Freedom (1987), ostensibly about murdered black South African activist Steve Biko, but from the perspective of his white friend Donald Woods, played by Kevin Klein. But this new trend in casting doesn’t necessarily move us beyond the western standpoint on Africa or the Caribbean.

MH: Sea in the Blood (26 minutes 2000) is a stunning work, deeply personal, wounded and lyrical. It narrates the story of your sister Nan who has a fatal blood disease, and marries this with the story of your lover Tim, who is HIV positive. This familial tragedy is filled with tenderness without ever becoming sentimental, and touches on difficult questions, allowing old hurts to be aired out with an inspired equanimity. How did you begin to structure this work? Was it difficult to speak to your mother about these past events? When did you know Tim would be part of the mix?

RF: It was awkward speaking to my mother about my missing my sister’s death as I knew it would take us back to a difficult place, one that neither of us really wanted to revisit. In the end I think it was cathartic: for her in getting things off her chest, and for me in hearing what she had to say and putting that pent up conversation behind us.

Tim was always going to part of that mix because it was through AIDS and the theoretical and political reflections and activism that it engendered, that I began to rethink thalassemia and my family’s history with illness and medicine. I always thought that my father’s pressuring all of us to study medicine had to do with a drive for upward mobility from his peasant background, but seeing four of his children die must surely have played into the mix. I was also interested in putting those two strands of my life together, as I set myself the challenge of intertwining—or colliding—established film genres including the Asian family drama, the AIDS narrative, the gay memoir. On the concept side I was influenced by writing and activism about AIDS, particularly Douglas Crimp’s essay “Mourning and Militancy” (Out There: Marginalization and Contemporary Cultures, ed. Russell Ferguson et al., Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990). Douglas Crimp was heavily involved in ACT UP New York, and when he talks about activists needing to also deal with loss and mourning, to confront emotions not just political agendas, it struck a note. I lived in a communal house that was a centre of AIDS activism in Toronto. My partner Tim and our housemate George Smith were founding members of AIDS Action Now! Everyone was involved to some extent. It was true that in the 80s and 90s so many people died and there was so much work to do to pressure governments for treatments, to demand rights for people living with HIV and AIDS, to fight for safer sex education and so on, that mourning was indeed less of a priority. Crimp uses psychoanalytic theory to talk about the consequences of neglecting to deal with the emotional fallout.

MH: Did you feel an overwhelming pressure during this pre-cocktail period to produce useful work, work which could be deployed in the struggle? What good could beauty bring when people were dying in such numbers and so near?

RF: I have never really made work directly tied to issues, that’s something I admire in the work of someone like John Greyson. John is able to take up current issues and turn it into art, but I’m not able to respond so quickly. I did do some work on AIDS in that period, though, like Fighting Chance (31 minutes 1990) which is a documentary on gay Asians and HIV done for a series produced by John and Michael Balser. I was doing AIDS work with the Gay Asian Aids Project, and was struck that the educational material that went out to gay men, constructed gay men as white. The material that was made for Asian communities constructed Asians as heterosexual. Gay Asian men fell out of both paradigms. I was in workshops with other gay Asian men who felt that AIDS was something that couldn’t happen to us. I attended one workshop with a man I knew to be positive, and who had come to the group seeking support, but the idea of being positive was so repressed he never disclosed. That was the reason I made Fighting Chance. It was filled with talking heads because it was important to show gay Asian men who would appear onscreen and talk about being positive.

I don’t recall thinking of Sea in the Blood as strategic; it was just a story I had sat on for a long time and finally wanted to get out of my system. I was nervous that anyone would want to see it, though, since as a programmer I knew that by that time audiences already tended to shun AIDS programs.

MH: Steam Clean (3:30 minutes 1990) is a safe sex bathhouse romp that follows an Asian male cruiser to his white-toweled consort. They kiss and jerk each other off, then one puts on a condom and fucks his new love. The titles “Fuck safely use a condom” appear as overlaid titles in a variety of languages. Who was this tape made for? What was the response at the time, and what is the response to the tape now? I was going to ask: is it still ‘effective,’ does it still work, and then had to catch myself. Would the same questions be asked of a painting or sculpture? Most art doesn’t carry the burden of eternity, and that’s a good thing, right?

RF: The question of efficacy is quite appropriate in this case, actually, as this was a commission by Gay Men’s Health Crisis in New York as one of their “safer sex shorts.” These PSAs were meant to play in clubs and other gay venues to eroticize and therefore naturalize the idea of safer sex. They were “community-specific” and I was asked to do the Asian one. I addressed some of the conceptual and theoretical questions that arose for me in an article titled “Shortcomings: Questions about Pornography as Pedagogy” (Queer Looks, ed. Martha Gever, John Greyson, Pratibha Parmar, Toronto: BTL/New York: Routledge, 1993). In this essay I tried to pull apart and examine the assumed relationships between subjects and objects of desire in a racialized context, and the (mal)functioning of sexually explicit images harnessed to an educational agenda. In the end, I have no idea about how effective it was at accomplishing its various intended goals, but it did receive quite a bit a play, including most recently at the Guggenheim in their retrospective of AIDS media.

MH: In your Shortcomings essay you write: “I met Jean Carlomusto and Gregg Bordowitz, video production coordinators for GMHC, in 1989, at a conference on gay and lesbian representation. Although I am based in Canada, they approached me to produce the “short” for Asians, presumably because they knew and liked my work, but also because they could not locate an openly gay Asian videomaker in the United States who would undertake such a project.” This comes as some surprise to me, while I don’t imagine there are cities packed to the brim with videomakers of any stripe, the fact that not one openly gay, American Asian media artist came to mind seems strange.

In the same Shortcomings essay you go on to write, “I already knew that in depictions of sex between East Asian and white men, the Asian man was almost invariably the “bottom.” I knew that this reproduced a stereotype that Asian men resented. I could not, therefore, portray the Chinese man as the “passive” partner in anal intercourse if I wanted East and Southeast Asian men—the target group—to get pleasure in the tape. But what about the other man? Was it less problematic to show a South Asian getting fucked because, as a group, they are rarely represented sexually in North America? And how did all of this relate to the privileging of penile pleasure and patriarchal assumptions about the superiority of penetration? In the end, I had the Chinese man penetrate, though I attempted to “equalize” the situation by having the Indian man sit on him, thereby asserting the pleasure of the anus.” I’m wondering if you would make the same choices today? You didn’t go on to make more art porn-why is that?

RF: I’m not sure I would make the same choice today because the context has changed and other video artists have taken on the question. There are some great subversive rejoinders to the whole thing. These include Wayne Yung’s Peter Fucking Wayne Fucking Peter (1994) and Nguyen Tan Hoang’s Forever Bottom! (1999). Both these tapes foreground anal pleasure in an erotic and a humorous way, respectively. Ming Yuen S. Ma also takes on these issues in several works.

As for art porn, it never interested me as a consumer or as a producer. I don’t find most attempts at the domestication of the porn genre successful—in fact, for the most part I do not find straight-up porn that interesting either.

MH: Why did you make Uncomfortable: The Art of Christopher Cozier (47 minutes 2005)?

RF: It wasn’t planned; I had a research production grant from the Canada Council for which I’d proposed a series of short works around sexuality and the nation state, looking at Canada and Trinidad and Tobago. I was interested in the fact that when Trinidad outlawed lesbian sex in the 1980s, it was a part of a larger set of legal changes in the Caribbean that brought lesbian sex under the law. Gay male sex, on the other hand, had been criminalized since the 1880s, when Britain introduced laws against sodomy. But Queen Victoria couldn’t imagine women having sex together, so lesbian sex remained un-criminalized.

MH: Why were lesbians criminalized in the 1980s?

RF: In Trinidad it was related to feminist inspired legal changes, which for instance allowed a man to be charged with the sexual assault of his wife. M. Jacqui Alexander, a Trinidad-born theorist who is now teaching at the University of Toronto, did a lot of theoretical work around this question, which is how it came to my attention. At around the same period Canada began accepting refugee claims based on gay/lesbian discrimination. I had been approached by a lawyer to write an affidavit for someone trying to move to Canada, and had to write convincingly about Caribbean homophobia. At the same time I was weary about rehashing old tropes of Third World backwardness. Besides, both Canada and Trinidad are more complicated when it comes to how queer people live their lives.

Anyway, I was in Trinidad doing research, talking to gay activists, but wasn’t satisfied with how the project was going. I didn’t want to do a documentary about gays and lesbians in Trinidad and Tobago but something more essay-like. Then I was introduced to Christopher Cozier by a mutual friend and saw his blackboard piece, which looked at a certain construction of a Trinidadian national identity and its relation to xenophobia and homophobia.

He uses an old fashioned black board, divided into two columns beneath the headings “Us” and “Them.” “Us” lists supposed national characteristics: people who work hard, love their leaders and so on. On the other side is “Them”: white people, rich people, bullers (Trinidad slang for sodomite, it’s connected to the word “bull” which means to sodomize). I was struck that an artist I knew to be heterosexual would take this on, and so we began different sorts of exchanges.

What fascinated me about Christopher’s work is the way he deploys that kaiso aesthetic I spoke about earlier in contemporary art. For instance, the way he deconstructs the use of wrought iron grating on windows. These can be found not only in Trinidad and Tobago, but also anywhere that social disparity leads to burglary. In Trinidad, Chris noticed how people began to treat them as decoration, and compete for original patterns. He responded by making eye glasses with the wrought iron pattern where the lenses should be, and two-sided cards with an identical image of a grille pattern on each side, but one says “inside” and the other “outside.”

Bars came onto our house only after I left in the 1970s. My sister became scared after a burglary so my father barred the windows. When I was young, people were just beginning to put them up, so it’s a relatively recent phenomenon. By now it’s become so naturalized people don’t see them anymore.

MH: How does Cozier’s work relate to larger currents of dissent in Trinidad?

RF: Christopher’s slyly critical stance is closely related to the quintessential Trinidadian art form: calypso. Non-Caribbean listeners may have only experienced calypso through its more recent manifestations like soca, or soul calypso, which is more pop oriented and sometimes devoid of content. But calypso is a critical art form. The calypso singer often uses very crude sexual metaphors or makes dangerous commentary on local politics or world events but escapes censure and censors through his or her verbal dexterity.

When the Americans established a military base during the Second World War, traditional morays were upset. My aunt married an American soldier, for instance. And as you would expect, there was a lot of prostitution. In his famous calypso Jean and Dinah, the Mighty Sparrow sings that these prostitutes would never give him a second look, but now that the Americans are gone he claims he can have any of them. “The Yankees gone, Sparrow take over now,” is one of the refrains in the chorus. Even the well known Rum and Coca Cola talks about mother and daughter working for the American dollar. I don’t remember if the Andrew Sisters cleaned it up when they turned it into an American hit.

Christopher’s art works are very much in this Trinidadian tradition. He nevertheless complains that at times he’s dismissed as having too much of foreign influence because he has a Master of Fine Arts from Rutgers University, and because he often shows abroad. In both Trinidad and Canada there’s an obsession with claiming and rejecting. I’m always struck when I open the papers and read that Keanu Reeves spent three years in Toronto as a teenager, or that Paul Haggis was born in London, Ontario. Trinidadians similarly claim but they also reject people much more often and fiercely than Canadians do—though remember how Ben Johnson suddenly became more Jamaican after the drugging scandal? Charges of foreignness are common. But if cultural and intellectual purity holds anywhere, it certainly doesn’t in Trinidad and Tobago, since as Christopher points out in Uncomfortable, the Caribbean was born in globalization as off shore production sites for Europe. Trinidad and Tobago has a population mostly brought in from Africa, Asia, Europe and the Middle East. The ways that people see themselves is in constant flux with transnational currents, so for instance even the Amerindian community has re-envisioned itself in recent years through contact with North American First Nations. This phenomenon isn’t just a matter of one-way passive reception either. For example, international figures in black consciousness like C.L.R. James, Stokely Carmichael/Kwame Ture and Michael X came from Trinidad.

For me what is going on in these debates about the local and the foreign are really different and competing visions for the direction of the country. So, for example, someone like Christopher would want to resist what he would see as the Miamification of Port of Spain in the development of shopping malls and gated communities. Yet someone who lives in a gated community might well reject the criticality and the contemporary forms in Christopher’s work as “imported.” This person might instead champion one of the many painters of local flora and fauna and quaint village scenes as representing true Trinidadian art and values. I’ve noticed that the wealthier the household the more ubiquitous are pictures of ramshackle houses and half-naked children. He or she may not know—or may ignore—the roots of their cherished local artworks in French and German painting of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

MH: You’ve shown work in Trinidad, are you a foreign currency?

RF: My work has screened there, but there aren’t a lot of venues for the kind of work I do. Trinidad is a relatively wealthy society. It has a petroleum-based economy and one of the highest per capita incomes in the Latin American region. But although there are several artists making interesting interventions, the art market is rather conservative and there is not a lot of backing for contemporary practice—no real grants, for example. The most exciting thing is CCA7, a contemporary art centre which houses a Canada Council residency and acts as a staging ground for interesting projects.

MH: Cozier’s political engagements seem to flow directly into and out of his art practice, everything around him seems charged with a post colonial current which he is busy rerouting into his work. His personal identity and his identity as a citizen seem very close, at least in part because he has lived through the departure of the English empire and the establishment of a Trinidadian government. Is that part of what drew you to him?

RF: One of the questions I asked Christopher was: do you feel like an activist? He said no, he is an artist. But his work features an ongoing aesthetic and political critique. He remains socially engaged: the tape shows him doing documentation in a neighbourhood colonized from the swamp by squatters, hoping that by bringing witnesses there and working with people in the community he can weigh in against the eventual destruction of this place. But he is not an artist whose work is about slogans; instead he tries to spark epiphanies.

Christopher is a bit younger than me, but we both came of age during the fervor of independence, with a new flag and the inauguration of television (given as an independence gift). When I saw his blackboard piece I recognized it immediately. It was installed in a large gallery before a flotilla of white bread sandwiches wrapped in wax paper. Each bore a tiny national flag hoisted on a toothpick. I had taken similarly wrapped sandwiches to school. I grew up singing God Save the Queen and then had to learn a new anthem when I was ten or eleven. Christopher and I share this moment of formation. His situation was different because his parents are both from the Barbados and came to work in the government, so there’s a way in which the nation was the bread and butter of his family. He also lived in a quintessentially new middle class suburb. Everything about his life is tied to a narrative of independence. A younger artist doing work about contemporary Trinidad wouldn’t have such an obsession with the formation of the nation and citizenship and the promises of that moment.

MH: In Dirty Laundry (31 minutes 1992) the remarks of historians, archival footage and onscreen text are woven into a present day “narrative” which takes place on a cross-Canada train. Researcher “Roger Kwong’s” great-grandfather was one of the thousands of immigrant Chinese workers hired to lay track. History, as you point out in the tape, consists largely of documents produced by those in power. Your project works the other side. Why did you reconvene history with these unusual layerings and why did you decide to tell these stories?

RF: I became fascinated with Chinese-Canadian history because I came from another Chinese new world context and was inserted into this one. The first Chinese came in small numbers as part of the gold rush, mostly from California. When the building of the national railway commenced the Chinese were encouraged to immigrate. They worked longer hours and were paid less than other workers. They sent money back home to China, usually assuming they would return to China. When the railroad was finished there was a head tax imposed on Chinese immigration. Then a Chinese exclusion act was introduced, barring all immigration, except for merchants, students and diplomats. It was very much a class imperative: if you were wealthy enough you could come, the law was designed to keep workers out. The class dimension to the immigration laws in the succeeding period has fallen out of the retelling of how restriction took place. I was interested in the way that class played such a strong role in Chinese-Canadian history, and how that has been evacuated from the telling of that history, whether in government commissions or advocacy documents. Those were the triggers for my work.

The founding image for Chinese-Canadians is the building of the CPR, the Canadian Pacific Railway, and around that the growth of bachelor societies on the west coast attached to mining or the railroad. Only after World War II were Chinese women able to immigrate in large numbers and families could take root. Before that, Chinese communities were mostly comprised of single men, which made Chinatowns such interesting spaces. In Trinidad there was never a bachelor society. Men came to work first as indentured labourers, but because of different racial hierarchies Chinese men intermarried with African women and later with Indian women. Most of the Chinese community in Trinidad is mixed-race. But because of the racial hierarchies in North America, the men remained bachelors, or married Native or Irish women. The Irish in that period weren’t considered white.

I was interested in the way that in the current period the Chinese are thought of as a model minority—industrious, hard-working, high-achieving, accommodating to the system—and used against other minoritized communities. This is so different from the dominant image of the Chinese in the nineteenth century, associated with gambling, prostitution and crime. These two opposing stereotypes have actually competed for a long time and if you look at the report of the Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration from 1885, you see both the positive and negative versions of the Chinese. I was interested in the importance of sexuality in these images—female prostitutes and male sodomites, or virtuous celibates. The negative images were pretty successfully cleaned up and repressed, though they surface every so often in stories about triads or massage parlours.

MH: Why did you reconvene history as a story?

RF: I’ve been long interested in the way that different forms have different abilities to communicate. Documentary relates certain kinds of truth, but fiction can communicate nuanced emotions. This arrived with the epiphany that what is considered avant-garde work is a fairly closed lexicon of gestures. It’s codified in the same way as a documentary interview. In my work I’ve moved between these different traditions. With Sea in the Blood, for example, I hired Carole Larson because of her experience editing fiction. I needed the technical construction of fiction to make the tape work.

Dirty Laundry has three layers: the proto-narrative (someone described it as the kind of narrative you see in a porn film, which is a good assessment) about a man riding cross country on a train, interviews with historians, and the historical documents brought to life as tableaux. I wanted each layer to undermine the other. Like many of my projects it’s an itch I’m scratching, an attempt to come to terms with something that’s bothering me. I wanted to undermine a variety of forms while allowing them to speak

MH: Whiteness was a term reserved for Anglo-Germanic countries, but broadened to include all of Europe in light of Asian immigrations. Pardon my naïveté, but why did so many public officials here in Canada (a nation of immigrants after all, usurpers of Native land every one) make so many unapologetically racist statements for the public record

RF: Well racism was official ideology at the time. Remember that slavery was only abolished in the United States a mere twenty years before. So they did it because they could, and they hoped the constituencies they were speaking for would agree. There’s a shifting bar of propriety determining which groups can be disparaged. We’ve seen this bar shift greatly in our own lifetime. In the 1970s people said the most outrageous things about homosexuals in public discourse without shame or embarrassment. Now even right-wing politicians like Stephen Harper have to code their homophobia.

Below today’s bar are terrorists and pedophiles. One can say anything about them and few would come to their defense. Today it’s hard to imagine the bar shifting to grant pedophiles more protection, but in ancient Greek societies certain kinds of pedophilia were the norm.

MH: You trace an early “gay” Asian presence in the multi-racial, largely male worker settlements attached to the railway. Bed sharing was a common practice, though most men wouldn’t openly identify as being gay. Historian Nayan Shah states: the idea that sexuality is an integral part of identity is brand new. Could you elaborate on this?

RF: Well that was Michel Foucault’s discovery, right? He looked at the way in Western society sexuality is seen to hold the ‘truth’ about an individual. In earlier European societies church laws inveigh against certain sexual practices, but those acts don’t constitute an individual identity. There’s a difference between what one does and who one is. When I came out to my mother, one of her responses was: why can’t you get married and have a family? In traditional Confucian society, so long as men fulfilled their filial duties, and produced offspring to worship their ancestors, no one cared about what they did outside their obligations. Don’t ask don’t tell.

This is different from the idea that you are what you desire. And that inner being matters to you and to society. This, though, is at the core of gay liberation: the task it to liberate the truth, the gayness inside, to bring it out of the closet. With the shift from gay and lesbian to queer in the last decade or so, this notion is slowly but surely being modified to accommodate a more fluid understanding of how sexuality works. In Dirty Laundry, the question for me remained: to what extent can one regard same-sex sexual activity in working class Chinese communities of the nineteenth century as an ancestor to present day Asian gays? The tape poses this question but avoids answering it. The audience is enticed to draw their own conclusions.

Videos

Orientations: Lesbian and Gay Asians 56 minutes 1985

Chinese Characters 20:30 minutes 1986

The Way To My Father’s Village 38 minutes 1988

Safe Place: A Videotape for Refugee Rights in Canada 32 minutes 1989

Fighting Chance 31 minutes 1990

Steam Clean 3:30 minutes 1990

My Mother’s Place 49 minutes 1990

Out of the Blue 28 minutes 1991

Dirty Laundry 30:30 minutes 1996

School Fag 16:35 minutes 1998

Sea in the Blood 26 minutes 2000

Islands 8:45 minutes 2002

Uncomfortable: The Art of Christopher Crozier 47:38 minutes 2005