Rick Hancox: There’s a Future In Our Past

Rick Hancox has been loading up first-person cinema for three decades now. Using the most modest of means, he has crafted an exquisitely edited, often brash and moving body of filmwork which is openly diaristic. Working the divide between private and public space, this is an intimate practice, made with friends and lovers, photographed in familiar places where the camera, as well as the conversation, is shared. Often transplanted as a boy, Hancox began in the 1990s to revisit former stomping grounds, crafting an elegant quartet of land and scape and memory which cuts to the heart of the Canadian Imaginary. For years he taught in Oakville’s Sheridan College, primal scene of the Escarpment School, offering many their first exposure to the work of the fringe. He continues to teach in Montreal’s Concordia University, championing a cinema that begins with a thorough shakedown of its first witness and the machines that make subjectivity possible.

RH: I began playing music pretty early in my life and by 1961 had a rock band called the Viscounts. The next year I had another, called the Tempos. They were cover bands, and I played guitar and sang. My parents suggested that rather than become a rock star I go to Mount Allison University for pre-med. I proceeded to flunk out two years in a row. They called me “the Cox” and I’d have these “Coxian auctions” standing on my residence bed, selling my books for booze money. I continued playing music, this time in a Mount A rock band called the Loids. By the third year the university wouldn’t let me back in. I headed to the closest big city, Montreal, to get a job in the real world, and wound up selling encyclopedias door to door. I was so good at it they paid me to teach others and I won a free trip to Rome along with the best salesmen in North America. We stayed in the Hotel Excelsior with live chamber music for breakfast. They gave us spending money, which I blew on hookers in the first forty-eight hours. I did manage to go on a tour of the Catacombs of San Sebastino, a maze of tunnels which run for miles underground. But when the tour was over I snuck back down on my own, running with glee. And then the lights went out. I froze. It was completely black and so quiet I could hear my heart echoing off the walls. I was wondering which direction to head in when the lights finally came back on, and I ran like hell to the door. Apparently they have frequent power failures, and people have disappeared in the maze, never to be seen again. I wrote a poem about my Rome experiences called “Yankee Via Veneto” which is quite entertaining. All my poems were based on real experiences. They’re documentaries. Later on I realized that my music and poetry could both find a place in film.

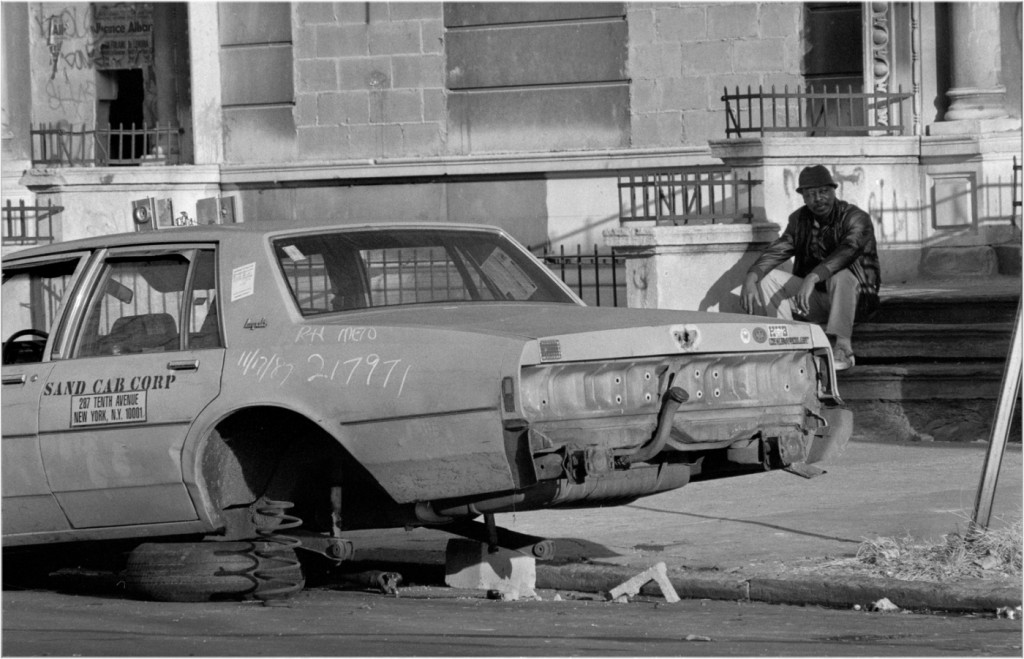

I wanted to go back to university and the only place that would take me was St. Dunstan’s in Charlottetown, which eventually became the University of Prince Edward Island. I had a good year there, and took a summer course called Eastern Thought which changed things for me. Despite my C grade I enjoyed it immensely. I remember lying in a hammock on the seashore wondering whether the tree was really there. How could we know for sure? I was starting to head out as a solo guitar act, writing my own folk songs, touring coffee houses in the Maritimes, until I missed so many classes I had to drop out of St. Dunstan’s my second ,year there. I started to feel my voice and guitar playing weren’t good enough, so I dropped out of music, too. I wound up driving taxi in Montreal for most of the winter. It was a pretty lonely job, working weekends, with people in the backseat heading somewhere better. One day, between shifts, I was in a bookstore and a couple of film books happened to catch my eye. There was a collection of Ingmar Bergman’s screenplays and Sheldon Renan’s Introduction to the American Underground Film.

MH: An early crossroads.

RH: I bought the Sheldon Renan book because it had great pictures! And was immediately sold on experimental film. I hadn’t seen one, but he describes the films so clearly and with so many illustrations, it was the next best thing. That spring I moved back to PEI and got a job as a night janitor in the student coffee shop. It was pathetic. My girlfriend in Charlottetown had broken up with me when I was in Montreal, and she was going out with some jock on campus. One night when I was cleaning, this mangy cat arrived carrying a mouse, and I watched with fascination as it methodically crunched the skull and then the body, until just the tail was hanging out like a piece of spaghetti. When the cat sucked in that tail, that’s when I knew I’d really hit bottom. That summer I bought a broken 8mm camera for a dollar, fixed it, and started experimenting on my own, as no one else I knew was making movies this way. I was shooting things that were around me, my personal landscapes. I started university again on the other side of town at Prince of Wales College the year it became a university, before it joined with St. Dunstan’s to form UPEI in 1970. George Semsel had come up from New York, where he was part of the underground film scene, to teach for a year. It was great timing. He taught PEI’s first (and last) course in 16mm filmmaking, and he showed us documentary and especially experimental work — still called underground film then. I don’t know how he did it all. The film department was in this old house which had flooded, ruining a lot of film stock, which George promptly used for the class anyway. We played with it, punching holes, scratching, projecting loops — George said we did everything to that stock but throw it up in the air and fill it full of buckshot. I made my first film, Rose (3 min 1968), with footage George gave me plus hand-coloured leader and scenes from the local news station’s garbage bin.

For my major project in university I shot another film, a short “poetic narrative,” but most of the negative was lost in transit and I had a month left to come up with something else. My father, who was publisher at the newspaper, said, “There’re so many stories in the paper, why don’t you see if there’s something there?” I came across a story about a taxi driver who’d won a Maritime Service Award. Before his regular calls he’d go around Charlottetown, picking up ,handicapped children and taking them to school. I shot it over a weekend, put the pieces together, and Cab 16 (6 min b/w 1969) won the Best Documentary Film Award at the first Canadian Student Film Festival in the fall of 1969.

That summer, wanting adventure, I set off for New York to live with George. He wanted to introduce me to his mentors, Willard Maas and Marie Mencken. They had a rooftop apartment in Brooklyn and Willard answered the door in his underwear. They were both notorious boozers. I’d brought my film Rose and Marie said, “I’m sorry, we don’t have a projector, but let me have a look at it anyway.” I was so flattered that Marie Mencken was looking at one of my films I let her unravel the whole fucking thing on the floor. She was saying, “This is amazing. Incredible.” Actually Rose looks even better that way, as an object, because of all the work I’d done dyeing and tinting. That was great. I hung my hopes on film-crew notices and volunteered until I got hired on for pay, just moving from film to film and looking after people’s apartments when they left town. I found work on this ridiculous film in Jersey City as a sound playback man. It was like a Busby Berkeley outer-space musical, made in 3D Techniscope for Expo ’70 in Japan. The director, who had flunked out of NYU, shot in Jersey City to get around the unions, so the set was filled with kids and drifters. One inexperienced rigger fell to his death from the scaffolding. My girlfriend had said, “There’s a great concert happening this weekend in upstate New York — why don’t you come with us?” I thought, no, I have to stay, I’m learning things here on set. That concert turned out to be Woodstock, of course.

MH: Didn’t you make Rooftops (5 min b/w 1971) during that period?

RH: Many buildings in New York have these old wooden water towers up on their roofs. One afternoon, I climbed on top of the recording studio where I was working and set up a tripod. I shot Rooftops there. Using a telephoto lens, I could pick details out of the surrounding rooftop landscapes reanimate these later through editing. Without any final form in mind, I began by simply recording what was there in front of me. After that summer I went back to college in PEI. Because there were no film courses, I started a film club and began doing workshops so other students could catch the fire. I was doing an English major, but I turned everything into a film course. Tall Dark Stranger (15 min 1970) was the result of some obscure independent reading course. I’d seen and liked Easy Rider in New York that summer but thought it was unfortunate the hippies got blown away at the end. One dream in the sixties was to turn on anybody from the establishment: the straight world, your parents, anyone. Stranger’s about a PEI farmer who’s visited by a hippie dressed like Christ. The hippie turns him on to hashish and the farmer has a vision of squealing pigs in positive and negative film, upside-down cows, and farm tractors. I hand-dyed this stuff like I’d done in Rose. The next morning the farmer’s still sleeping it off when the Christ figure packs up, leaving behind a big block of hash (actually toasted chewing tobacco) and walking across the water of the frozen pond in his sandals.

MH: There’s an odd sexual tension when Christ reaches into his toga.

RH: He’s got the hookah stored underneath his robe, and when he reaches in to get it there’s a lot of cutting back and forth between him and the farmer, who’s wondering what’s going on. After the hookah comes out they get stoned.

MH: It’s wonderful that this psychedelic western should take place in Prince Edward Island. The dope communion is something these two generations can share, allowing the son to triumph over the father, but in a very gentle and funny way.

RH: After school I taught film at summer camp, where I met Barbara Holland, piano accompanist for the ballet program. I moved into her upper-west-side New York apartment along with her two teenage kids. Barbara was sixteen years older. We loved each other but she carried her family’s troubles. Her mother committed suicide and killed Barbara’s baby sister in the process. Her father was a gold-mine speculator, which kept them moving from town to town, where he’d start up his scams and have to move again. He wound up hiding in Guatemala with Barbara’s brother, who had abused her, and she hasn’t spoken to them since. After her mother died, she was brought up by her wonderful grandmother near Buffalo. Barbara studied piano, read voraciously, and went to New York City to seek her fortune. She was eighteen and got in with this artsy crowd, well-known up-and coming actors and musicians. She’d gone out with Marlon Brando when he was on stage in A Streetcar Named Desire. She told me some funny stories about Brando. There’s a scene in Last Tango that’s right out of something he said to Barbara, about how he arrived at the school dance with shit on his shoes from milking the cows. To a kid from PEI she was a sophisticated, remarkable woman.

I spent a year at New York University. The film program was very restricting but I learned a lot about photography from Paul Caponigro, and also from John Szarkowski at the Museum of Modern Art. His notion of photography included amateur and chance photography, things that were never intended to be art. That was important for me. We studied Cartier-Bresson and I wondered how his notion of the decisive moment might be adapted to cinema to create an extended moment in motion. That’s when I started work on Next To Me (5 min b/w 1971). I started living inside these documentary photographs. Seeing them everywhere. I’d make lists of decisive “movements” that couldn’t be defined by a single picture — like garbagemen throwing refuse in slow-motion. A single photograph wouldn’t have captured the ironic grace of that. Next To Me begins with a man who comes to a stoplight, and while he waits for the light to turn he starts to think his Canadian angst in the big city. The film proceeds for about five minutes, then the light changes and he disappears into the crowd. He sees things that are metaphors for his own psychological state — a liquor store window with an inflatable Santa Claus which collapses, a woman falling naked on the camera, Bowery bums with squeegees — and later he contemplates jumping off the 59th Street Bridge, but can’t muster up the guts to do it. The funny thing is I didn’t know it was a personal film until editing it a year later. It was about the people and events in my life, but obscured by my “theory” of the decisive movement. Then I realized the actor is playing me! So the soundtrack includes bits of theory read in voice-over as a self-parody. I sort of satirize myself in several of my films, I don’t know why. When you can see yourself as a character walking through life … it’s a coping strategy, I guess.

It disturbs the hell out of some filmmakers. Bashing presents over each other’s heads in Home for Christmas was seen as a threat by conventional “concerned” documentary filmmakers. You just don’t do that if you want to be taken as a serious artiste.

MH: You finished your schooling in Ohio.

RH: Yes, George was teaching there by the early seventies and invited me to come and finish my MFA degree. One of the things I found in film school, especially at NYU, was that people were inordinately impressed with the biggest cameras they could find. Real filmmakers used an Arriflex and a big crew and drew a lot of attention to themselves. When it was my turn to use that technology I said no. I used a Nagra tape recorder but also a wind-up Bolex, wondering what would happen if we tried to make lip-sync films without the proper equipment. I loved the Bolex because it was portable and felt more natural with its springwound motor.

Wild Sync (11 min 1973) is in two parts. Lorne Marin had come down for Christmas, so we’re opening presents, playing music, and clowning around. Barbara’s on piano and her daughter, Nicole, appears as a Spanish dancer. That’s intercut with black and white shots of me filming myself in a mirror reading a script about how to make the kind of film we’re actually watching. As I’m speaking it’s drifting out ofsync and I say, “You can just cut out a few frames like this,” and you see the splice right onscreen and the film goes back into sync. The idea is to do everything myself. I’ve got the tape recorder over one shoulder with the microphone sticking out of it, the camera’s on the other, and I’m holding the Bolex on my shoulder by gripping its auxiliary viewfinder in my teeth, so my hands are free to make the sync mark by clapping my hands.

MH: It’s hilarious watching you wrestle with all that equipment. And the other scenes have great warmth and intimacy.

RH: We all had fun doing it. It’s a real document of the time. As you can see in the film, Barbara and I had got back together. We broke up in House Movie, made the year before, but by this time we were married.

MH: How did House Movie (15 min 1972) start?

RH: One of Barbara’s favourite composers was Rachmaninoff, and we liked to listen to his second symphony. That led me to thinking about our troubled relationship. I’d left New York partly to get away from us, then got lonely in Ohio, and coaxed her and her daughter to move in with me. And once again we tried to break up and take separate apartments. Rachmaninoff became an accompaniment and underlining of this impossible relationship. I’d already made a couple of autobiographical films and thought this one would make some sense out of things. We talked about it a lot and she participated in it very willingly. She didn’t feel it would amount to much, but it was part of my thesis work and I guess she could see it meant a lot to me. I shot in our rented house that December, panning over photos on the countertop, the furniture, little details of personal life. There are shots of us eating supper, going to sleep and turning the light off, me getting into a bath. Then I arrive with the moving trucks and our stuff is taken away. I go up the stairs of my new place, this godawful bare room. The final scene is a recapitulation, in which the camera tilts up the outside of the old house again, only snow has fallen. In the spring Barbara moved back to New York. I edited the film when she was gone, following the Rachmaninoff. I studied the score and gave the film a symphonic structure, with repetition and recurring motifs.

MH: Is it hard to show because it’s so personal?

RH: A little. I think it’s a really well made film, but I was always concerned about the music being too much. I’ve considered releasing it as a silent film, because the music would still be there in the structure.

MH: How did you wind up teaching at Sheridan College?

RH: I wanted to get back to Canada; I’d been in the States for three years and missed it. George Semsel was a model for me not only as someone who made personal films but as a teacher. I liked the fact he could teach and keep learning and earn enough money to pay for his films. I went through lists of film schools and liked the way the media arts department at Sheridan College sounded. When I got the job I wasn’t planning to stay long. Whenever I got pissed off I’d say, “Well, that’s all right, I’ll just quit. I’m either doing it my way or I’m leaving.” I didn’t have family, debts, or commitments, I could teach what I wanted, and I was finally able to wrangle an apprentice course where I could work on my own films with certain students helping. That’s how all the poetry films were made.

MH: You made a lot of films in the early seventies and then slowed down.

RH: There was a five-year break until Home for Christmas (50 min 1978) came out. Why? In Toronto I lived with Barbara in a now-condemned apartment next to the National Ballet School where she was working. Our tormented affair kept on: living together, splitting up, living in little rooms — I must have moved six times in one year. This went on for several years. Those first two years (1973–74) were a write off. I was an emotional basket case. Finally we broke up and that fall I decided to shoot Home for Christmas. My father had a heart condition and I was afraid that every shot I took of him might be the last. I phoned him and said I’d be bringing a camera and he said, “Aw, Richard, you’re going to ruin Christmas.” Of course he turned out to be the biggest ham in the movie. It was all shot in December 1975 and edited over the next three years. It was made on a two-to-one shooting ratio and used the wild-sync technique seriously this time, all shot very spontaneously. It was a direct cinema impulse — whatever happened happened, and I’d film it. I figured if I shot enough, the editing would show the relationships between various family members, between landscape and memory, and would evoke certain rituals of Christmas and homecoming and trains in Canada. After shooting the film there was a hiatus. I was missing Barbara again, so I’d go see her, then still see other women and feel guilty. I was totally depressed, living in this hellhole of a bachelor apartment while Barbara lived not far away, knowing I shouldn’t see her and thinking it would never end. Suicide even crossed my mind that summer. Needless to say, I did no film work. The next fall I met Cara, now my wife, and started to enjoy living again. A year later the film was finished.

MH: Your parents are central to the film. Are you close?

RH: I really admire my father. He’s well liked and has an admirable capacity for work that would be hard to equal. At 76 he was in charge of raising corporate donations for the University of Prince Edward Island. I respect him but we don’t have a lot in common. He’s been a pretty good father. My parents weren’t unsupportive of film, though at first they didn’t know what the hell I was doing. Which is okay. I learned long ago that in this fringe type of filmmaking you have to pat yourself on the back. My mother doesn’t like many of the films or she’s not interested. I don’t think she’s a very contented person; something stopped for her during the Second World War. When she was fifteen the Germans blitzed Manchester, and they had to leave in the middle of the night on Christmas Eve. She never saw her house again. She married in England at nineteen and came to Canada right away. I was born in Toronto sixteen months later. There’s a line in Home for Christmas when my ,mother says, “We grew up together.” We were close during my first five or six years, before my brother and then my sister were born. My happiest memories of her are from a long time ago. On the other hand, it’s really thanks to her I was brought up with an interest in the arts at all — certainly the public schools I attended never encouraged that kind of creativity, especially for boys. But I’ve had a troubled relationship with my mother — both her and my dad had parents who were born in Victorian England, where children were to be seen and not heard. There were, of course, proper ways for a boy (a.k.a. “a young man”) to behave, and young men should follow certain career paths and not others. Along came the sixties just in time for my teenage years, so experimental film became a kind of home base, a place where I could escape formalities and dissent and be irreverent.

MH: You took Home for Christmas to the Grierson Film Seminar.

RH: The Seminar’s no longer held, but it was a retreat hosted by the Ontario Association of Librarians, which brought together makers and users of documentary films. Every year different curators brought new work, and each screening was followed by a long discussion. Some British Marxists were invited to show their work, mostly polemical political tracts, which quickly developed an atmosphere of confrontation. Along came Home for Christmas, which was immediately criticized for being self-indulgent, a celebration of bourgeois values with “frenetic” camera work. Someone asked how such an amateurish film could be programmed at all. How could I be teaching film? Hadn’t I ever heard of a Steadicam? It seemed like I was going to fall into one of my deep depressions. I knew Mike Snow and Joyce Wieland fairly well at this time. I’d served on the Board of Canadian Filmmakers with Mike and done the neg cutting for Rameau’s Nephew. I felt I had no one else to turn to. So I phoned them both in Toronto from the Seminar and they were really supportive. Mike said I must have done something right; the fact that it provoked so much discussion and controversy proved I was onto something original. That saved me.

MH: Your next film was Reunion in Dunnville (15 min 1981).

RH: I was thinking about making a film that included scenes about my father and his World War II experiences in the Air Force. I did some research into the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, which had bases across Canada during the war, and came across a newspaper article that said that every year since 1946 there was a reunion of these veterans in Dunnville, Ontario. I wanted to go down and check it out and mentioned it to one of my students, Rick Hannigan. Rick said that both his parents trained in Dunnville, met and married there, and still return each year for the reunion. Four of us went down, including Phil Hoffman, and shot everything we could. What I didn’t know was that the base had now become a giant turkey farm. Filming from the car, we rounded the corner of one of these big hangars, and all of a ,sudden there were thousands of turkeys everywhere. That evening held one of the most incredible epiphanies of shooting I’ve ever had. The sun was setting, we’re out on this tarmac, weeds growing through it, and you could almost see all the layers of time simultaneously — a real temporal landscape.

MH: Could you describe the film?

RH: Reunion is my most conventional documentary. It centres on the day of the reunion. The memorial service is held in the shadow of an old Harvard training plane. The veterans stand at attention while the names of those who died in the past year is read aloud. Then I had the narrator read the names of those who died in training accidents during the war, while the scene dissolves to the empty airbase with its weeds and rusting hangars and the sounds of planes taking off, and then we go back to the service. The past is evoked through the soundtrack music, making a continuity between past and present. They’d recorded some of their early reunions on 16mm Kodachrome, and I used that as well. It’s one of my favourite films I’ve made.

MH: What was the Toronto filmmaking scene like during the seventies?

RH: I was involved for several years in the Toronto Filmmakers’ Co-op, a place run by and for filmmakers. But a new coordinator got railroaded in, moved the place, bought a lot of equipment no one could afford, and it went bankrupt. They thought they could turn the co-op into a commercial venture as part of a feature industry concocted by the infamous tax shelter. Meanwhile, at Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre they wanted to separate the “commercial” work, which would sell to libraries, from the “experimental” work, though when I joined all the work was experimental. I felt it was a way of ghettoizing experimental film. The Distribution Centre, the Co-op, and Cinema Canada used to share the same building but finally they all went their separate ways and then the Co-op collapsed. Out of its ashes were born two institutions: LIFT and the Funnel. The Funnel represented the experimental side and LIFT hosted the folks who wanted to step up to feature films. The Funnel was not the friendly place the co-op used to be. It was run by Ontario College of Art graduates who wanted desperately to be recognized as artists. They invented a publicity machine with the idea that all you had to do was tell people it was art and you’d receive grants and recognition. It wasn’t about making good work but good rhetoric. The Toronto film scene became an unwelcoming place, overly conscious of image and trends. By the mid-eighties I’d had enough of an arts scene that was increasingly insular, divided, and ugly. When a job came up in Montreal, I took it.

MH: Tell me about Waterworx (A Clear Day and No Memories) (6 min 1982).

RH: My father grew up on Neville Park Boulevard at the east end of Queen Street in Toronto. We lived with his parents in that house for the first year of my life. When I was a baby my mother would push me down to the waterworks at the foot of the street and look out longingly over Lake Ontario. There weren’t lakes that size in England, where you can’t even see the other side. The waterworks was named after my grandfather’s boss, Rowland Harris, Commissioner of Public Works, who lived across the street on Neville Park Boulevard. Grandfather was a city engineer who was working on the Toronto subway when he died — the same year I was born. When I moved back to Toronto as an adult, I’d drive around these buildings, thinking they invited some kind of filmic treatment. I wasn’t terribly interested in the fact that it was a water filtration plant. For me it represented an intersection of time, memory, and technology. I made tests in super-8, shooting from the car with twenty pounds of air let out of the tires. Then, on a cold, clear November day, using a low-speed colour reversal stock, I drove around these buildings. But I didn’t know what to do with the footage. Like all of the poetry films it was shot years before it was finished. Years later I came across a poem by Wallace Stevens called “A Clear Day and No Memories,” which seemed to be relating the mood I experienced with the waterworks. The film was just three minutes long, the soundtrack a mix of wind, radio static, and the wartime song my mother sang to me, “The White Cliffs of Dover.” Then all of the images repeat for another three minutes with the same soundtrack, but attenuated, and you see Stevens’s poetry stamped out on the screen by a computer. The notion of a technological memory imposing itself was very important, preventing access to the eidetic imagery in the background.

MH: Seeing the film repeated draws memory into the act of viewing.

RH: Viewers can’t have the images the way they see them the first time because words are in the way. The film transforms a sensual, visual experience into an intellectual one, which is how memory recall works. My father told me that before the plant was built there was a park where children tuberculosis gathered to take air. Others told me you can still find pieces of beautiful worn glass on the shore, because a glass factory preceded the park. It’s another one of these places with layers of time. While my personal memories were the only ones I was aware of, they brought me in touch with others.

MH: Waterworx began a trilogy of poetry films.

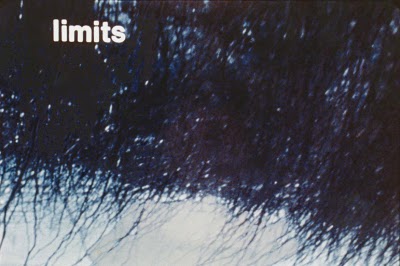

RH: Landfall (11 min 1983) and Beach Events (8.5 min 1984) were both shot in the seventies. The experience of making Waterworx helped me to go back and rework this footage, this time using poetic texts. Landfall was shot on the south shore of Prince Edward Island, where my parents had built a house, and the film was shot after I’d come home for Christmas. There was a big storm the night before, with ice floes forming in the straight, and I felt inspired that morning. I grabbed the camera and began dancing with it on top of the cliff, then down on the beach, making figure eights and lasso movements. I shot in slow motion, with the shutter closed down to enhance sharpness. That became the first third of the film. The rest is slowed down even further; I had every frame printed twice and then mirror printed. A copy of the original was made backwards and upside down, then printed back onto itself. So the two pictures move towards each other, circling around the still point of the centre. The only time the image stops is when I freeze-frame it onto my shadow or a glimpse of my hand. I came across a poem by D.G. Jones called “I Thought There Were Limits,” which fit very well. He wrote it after the breakup of his first marriage, so while he’s writing about limits to gravity and Newtonian notions of physics, he’s also speaking of emotional limits. The poem is spoken in the first third of the film, then reappears later onscreen. I used selected words, treating them as visual objects, parking the word “limits” at the extreme corner of the image, having others float up the frame, while some are upside down, defying gravity.

MH: The film has a tremendous exuberance and joy.

RH: One of his great lines is “Relax. The void is not so bleak.” The space of the film, where sky and ocean meet, seemed a void, but there wasn’t anything frightening about it to me. I find it rather comforting to know nature is greater than us. Historically, the Canadian landscape has been regarded as terrifying because of its vastness, but I’ve never seen that as a threat. Landfall was shot in the winter of 1974 and finished nine years later. It was named after the house my father built there. When you’re on ship and sight land, that’s called landfall. And of course the film shows land falling away. We had that ocean property for years before the house was built. I shot Beach Events the next year. I went down to the same area every day for a week, determined to shoot something different each day and make a seascape diary film. It begins with long shots and each day draws closer to the marine life. I remember showing the footage to Tom Urquhart at the Distribution Centre who said, “You don’t need to edit this film. It’s fine the way it is.” I thought he was crazy. I started pulling it apart, trying everything, but it never amounted to more than a lot of pretty seascape shots. Finally the workprint was so ruined I had another made, which showed me the original order of the shots. And it dawned on me that Tom was right! It’s an imprint or index of my experience. I move closer to nature, disturbing the flora and fauna. There’s a sort of backlash as the tide forces me into a cave. I seem to re-emerge a changed man, realizing I’m part of all this. Then the film reveals a merging of beach events above and below the surface of the water, closing with a shot of the horizon in which you can’t tell where the ocean stops and the sky begins. The text is inspired by Polynesian poetry, which is much like haiku writing; both are concerned with the present tense, describing simple “events.” I wrote a poem based on what we see in the film and superimposed it on the picture. There’s another poem spoken on the soundtrack written in an “automatic” style by George Semsel in response to the film. I read this poem and at the end I put this reading through a pitch changer. It becomes an anima or child’s voice merging various selves and nature. Like the rest of the poetry films, it’s a meditation on a personal landscape.

MH: Each of the films in the poetry trilogy tells the story of a place that is re-encountered through language. The movement between a thing and its naming is conjured here as the work of memory.

RH: So many of my films had been direct autobiography without commentary, but that changed in the eighties. I was very influenced by Wallace Stevens, who felt that poetry was a way of bridging reason and imagination. Words were allowed.

MH: Tell me about Moose Jaw (There’s a Future in Our Past) (55 min 1992).

RH: It started in 1978. After the Grierson Seminar, which had a lasting political effect on me, Cara and I decided to get the hell out and drive across Canada. I took a bunch of films from the Distribution Centre and showed them across the country. When we arrived in Moose Jaw I just started shooting without any idea of making a film; I just didn’t know if I’d get out there again. The footage of Moose Jaw on this first trip was mostly exteriors of buildings that I recalled: my old house, church, and school. I was overcome with feelings while I was there, frozen into long, passive camera takes, and while I was having dinner with Cara she asked, “What’s wrong?” It took me twelve years to answer her.

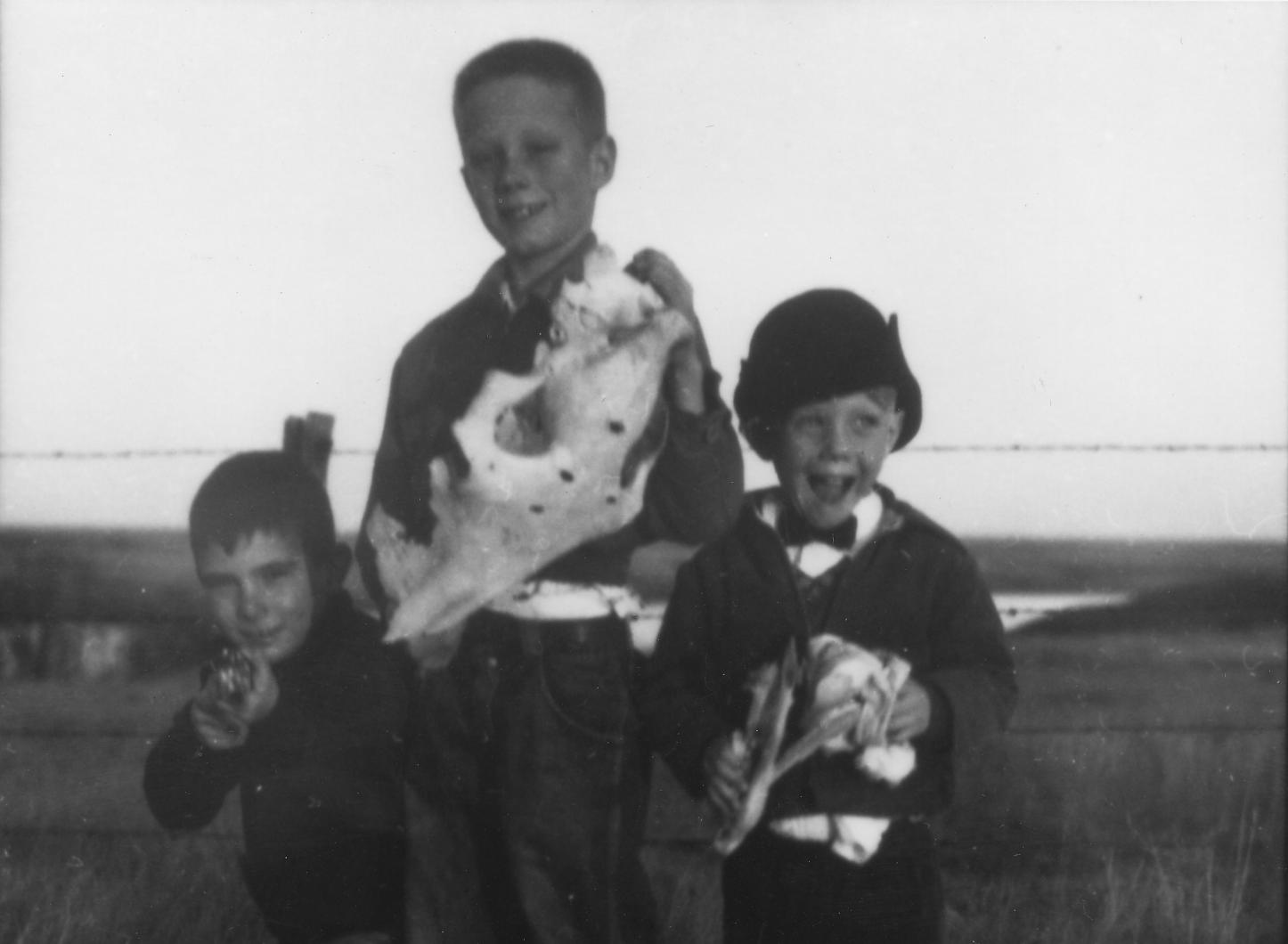

MH: When did you live in Moose Jaw?

RH: We moved out there in 1948. After spending the first two years of my life in Toronto, the next eleven were spent in Moose Jaw. Dad talks about what it was like when he arrived, still a kind of frontier town, full of WWII optimism. It used to be a frontier boomtown, chief red-light district of the Prairies, hide-out for Chicago gangsters and important rail station. Everyone seemed young, starting afresh, with no interest in the past. There was a military base built south of the town during the war as part of the British Commonwealth Air Training plan I was telling you about. A lot of my earliest memories are accompanied by loud Harvard training planes flying overhead. One of them crashed into a passenger plane above the city and forty people died. My father was one of the first on the scene, and I’ve been afraid of flying ever since. That’s why I always take the train. Our leaving Moose Jaw for Prince Edward Island after I turned thirteen in 1959 happened to coincide with the end of my childhood, the beginning of the sixties, the “jet age,” and the start of Moose Jaw’s long decline.

Like a lot of prairie towns, it was built because of the railroad, but that’s lost its significance. The province always relied on one crop, wheat, and they’ve just gone through nine years of drought followed by too much rain. Moose Jaw has the largest over-sixty-five population in Canada. When most return to their hometown they don’t recognize it because it’s grown so big, but Moose Jaw was just the opposite. In the years I was away, it shrunk. The town looked just the same, with the same buildings, only now they were closed or boarded up. The Temple Gardens, for instance, was a big-band dance club during the thirties and forties. Now there was a sign saying, “This building will soon be gone but the memories will linger on.” I went over to the newspaper where my father used to work and asked if they knew anything about it. They confirmed the building would be torn down, but no one really cared. I filmed the Gardens with the sign attached and we pushed on to Vancouver. When we came back a few weeks later the building was gone — only the sign was left. That was really the beginning of the film. I needed to get back and shoot more. Every excuse I had to go out west for a screening or conference, I took a train and stopped in Moose Jaw. Chris Gallagher was teaching at the University of Regina and offered to shoot for me. He got into the Moose Jaw archives and found stacks of unfiled pictures: a store that sold tombstones, a mechanical dinosaur. We’d confer on the phone about what to do next. One year I shot the archives myself. The camera tilts down over binders containing tattered newspapers in this dingy old room. Mining through the strata of time.

When I moved to Montreal in the mid-eighties I met Arthur Kroker, who was also teaching at Concordia. I showed him some footage, and he invited me to show it in his class each year as it developed. He called late capitalism an excremental culture. In the summer of 1988 all the sewers backed up in Montreal and our basement was flooded. When I opened the cans this terrible smell came from a culture growing inside, and because it was backup from the sewers, it was really an excremental culture! I had it rewashed at the lab and restored it, but as I tilt down over the archives you can still see some excremental stains flashing.

One night Alan MacKay visited in Montreal. He’s a Toronto painter, originally from PEI, and I’ve known him since we went to school together. I showed him some of the footage, saying I just wasn’t sure how to approach it. I had thousands of feet of film, newspapers articles, research on the history of the west, the subjugation of the Natives, the killing of the buffalo herd, radio reports. But how to put it together? The film was still composed of these very long shots, and midway through I got up to adjust the screen, casting a shadow of my body. Alan said that was the best part. “You’ve got to do more of that. Interact with this footage.” I decided to head back to Moose Jaw one last time. They were killing the rail service through the southern Prairies, so I hopped on the last train with a script in my hand and a cameraman waiting for me on the other end. He’d shoot scenes of me filming with a Bolex. There’s a sequence where I’m in the Transportation Museum filming a Model-T Ford, and I got the urge to hop up on the display myself. I became one of the wax figures, holding my old Bolex, because Moose Jaw couldn’t care less about the problems I was having with my personal memories. I was a relic, too. It all came together in 1989.

MH: Who were the Moose Boosters?

RH: They were a gang that dominated Moose Jaw politics years with crazy financial band-aid schemes to stimulate the economy, like turning River Street (the former red-light district of the Prairies) into a giant casino. After voting themselves raises during the worst Prairie drought since the thirties, they were voted out. This is revealed in an interview with councillor Brian Swanson, who was part of a new generation at City Hall that frankly admits Moose Jaw’s economic plight and the need to look after its aging population. My discovery of him in the film marks the turn of my satire inward. After a street parade, I disappear, and the camera commences a kind of search, only to wind up at the Western Development Museum again, this time tracking by what looks like a wax figure of me, Bolex in hand, arrested in the midst of filming one of the displays. Part of the waxworks. There was a tour of the Museum of Civilization in Hull a month before it opened during which an official bragged about how he was going to implode all of Canada in his establishment. It was unbelievable. The country had spread from Ottawa as an act of parliament, but was now collapsing like a dying star. I used his voice while we’re looking at scenes of Moose Jaw and shots out the train window, as if this was also museumized. There’re bits from the Moose Jaw radio station — Brian Mulroney’s speech after Meech Lake, CBC items about the closing of the railway.

The film ends with me desperately trying to film inside the closed and darkened railway station before I leave in the middle of the night, headed back east on “The Canadian.” The scene outside my window gradually becomes a blurred view of rushing scenery, first going east, then west, then east again — shot at various times of year. Finally I’m shown asleep, head thrust back against the window, as the Canadian landscape flashes by in perpetual motion, gradually burning out as the film roll comes to a flaring end in the camera. Meanwhile Brian Mulroney’s electronically distorted voice announces how he is “Saving VIA Rail,” while the cuts are detailed through the train’s broken PA system. Because I’ve lived all over Canada, I don’t feel like I have roots in any particular place. I feel at home both anywhere and nowhere at all. That’s why the film ends on the train. As if it were home.

MH: Why did you subtitle the film “There’s a future in our past”?

RH: During the eighties there was a renovation project where you could get a matching grant from Ottawa to renovate your main street. Moose Jaw received funds and rebuilt their beautiful old light standards and really dressed up the street. You’d never think it was the main drag for a town of only 30,000. At the foot of Main Street looms a beautiful CPR train station. But there were a lot of “false fronts” and behind there’s not much. The motto of the project was “There’s a future in our past,” which seemed to symbolize everything that had gone wrong. It had been a young progressive place and was now turning into a city whose only future was in commodifying its own past.

MH: It’s been years since Moose Jaw and you haven’t finished up anything yet.

RH: It was so hard to make that film, it took so much out of me. And you always want to do something more than your last film. I just don’t know if I can do anything much better. I put everything I had into it. I still love film, but I’m not sure anyone really wants the films I make.

MH: Tell me about “redeeming time.”

RH: My wife was looking into the history of the Hancox name. Many names have a slogan or emblem attached, and she found out the Hancox motto was “Redeem time.” Which is what I’ve been trying to do all these years.

Rick Hancox Filmography

Rose 3 min 1968

Cab 16 6 min b/w 1969

I, a Dog 7 min b/w 1970

Tall Dark Stranger 15 min 1970

Next to Me 5 min b/w 1971

Rooftops 5 min b/w 1971

House Movie 15 min 1972

Wild Sync 11 min 1973

Home for Christmas 50 min 1978

Zum Ditter 10 min b/w 1979

Reunion in Dunnville 15 min 1981

Waterworx (A Clear Day and No Memories) 6 min 1982

Landfall 11 min 1983

Beach Events 8.5 min 1984

Moose Jaw (There’s a Future in Our Past) 55 min 1992

Originally published in: Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada, ed. Mike Hoolboom, 2nd edition; Coach House Press, 2001.