No never not me

SARS

I am from the city of SARS. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. Like any respected illness, it is quickly spread, highly contagious and fatal. Without warning, the city I’ve lived in all my life has been converted into a plague epicenter. Again.

Like me, the television has no memory. It doesn’t matter what happened before. There is only now. I live in an eternal and ever expanding present. I am from the city of SARS, always have been.

The first case was uncovered only a couple of months ago and the headlines followed soon after, hospitals were secured, health officials appeared so often in the media we wondered if they had time for much else. Their pictures are intended to calm and reassure, though Toronto is a city so concerned with work deadlines that anything as involving as panic would have to be planned and inserted into already crowded civic schedules, squeezed in between gulps of cappuccino and committee meets.

Toronto is a city built on the superego, requiring endless sacrifice, tireless work hours and devotion. SARS could not be better contained anywhere else. Toronto’s citizens have already swallowed the watchful eye of conscience, the surveillance cam of the imagination belongs to each of us, as we perform our rituals of greeting and leaving. While part of us is always here, in the moment, in what grammarians like to term the present ‘tense,’ in close-up, the other part is always in long shot, looking at ourselves from a very great distance. This is the distance of the superego, the judge, the one for whom nothing is ever enough. Not even SARS.

Along with a new disease, a new word makes the rounds of the city, at once quaintly old fashioned and terrifying. It is a word so powerful it threatens to loose the hold of the microchip which has already possessed us in a viral replication all its own, converting our everyday into two kinds of time: on-line and off. Cowering beneath its three syllables, the steady march of progress itself seemed in doubt, threatening to turn us into a living museum of the middle ages. Quarantine. They were actually talking about putting people in quarantine. Maybe the whole city, who knows? For this contagion could pass through the air. Lie waiting on door knobs and elevator buttons. No surface, no matter how familiar, could be entirely trusted, assumed benevolent, safe. This is part of the power of a plague, like an avant work of art, it overturns assumptions, upsets the easy jog between experience and its naming. It is a contagion of the imagination.

Of course I acted like everyone else in the midst of catastrophe, I ignored the whole thing. Shut off the radio. Refused the news. This plague might be killing people but not me, never me, my friends and neighbors. Because I grew up on books, I thought if you scratched hard enough at anyone afflicted you would uncover some psychic tremor, some moment of ill will that lay in wait, festering for an answer like this one. Ridiculous I know. That our life might be broken into chapter summaries, cover copy, even appendices and a bibliography, this hardly seemed unlikely, not after so many centuries bent to the rule of the book. But to imagine that scripture might apply to something as even-handed as the plague, that was more than a stretch. The tabs were running pictures of the youngest ‘victims’ they could find and splashing them all over the city. The innocent are dying, they fairly screamed, and if the blameless could fall, well, then who was safe exactly?

Armed with this plague, we stood at last beyond the law. I washed my hands at every opportunity, just as the doctors prescribed, but more than that, I answered every phone call, met every request, cast a benevolent eye wherever I went. I would ward off illness one smile at a time. Make a forcefield of virtue.

Because no one I know comes down with it, SARS remains a media confection. How confusing when Jay from San Fran calls to ask, “Is it safe to visit?” He has a child now, a young boy, so the ledges he used to jump off without thinking twice seem a little steeper. A new kind of vulnerability has entered him and with it a new kind of fear. He’s calling for more than assurance, he would like to receive a guarantee of safety, something so bright his boy will be able to make it out across the continent. I imagine the bird men of Minsk, the hooded saints of Venice, the phallic warriors of Bremen walking untouched over cobblestones that had not yet felt the fury of blitzkrieg; five hundred years ago the machines of death were slower, but no less terrible. These masked visitors, witches and fantastics, were amongst the few to enter cities whose very mention, or so legend has it, was enough to prompt illness. Crossing ramparts filled with soldiers armed to contain this empire of illness, who would dare pass between them except for those who had died already? But I don’t tell this to Jay, I have no mask of feathers to protect us, no insider’s deal I can offer that will spare him. According to the papers at least, the prospect that he would come and visit me and then die, leaving his child destitute, seems unlikely, but not impossible. Every decision, Jay reminds me, leads to the end, and as he says the words I can hear the small terrible place inside where his boy is always getting hit by the bus, thrown into the path of a motorboat, pianos fall from the sky to crush him, cracks in the pavement swallow him whole. For their parents, children are also a kind of plague. Two weeks later Jay comes down with fever, and calling me from a feinting, vomit filled sickbed he sounds happier than I’ve heard him in a long time. The decision has been made for him. He won’t have to come.

Losing It

There is a way of forgetting events even as they happen.

Last year I fell in love with Srin, an ubermind from Brussels. We had exchanged The Look over a decade of festivals and incidental meetings, secreted the love gas that says yes, you, I want to reach into the very heart of you and travel the seams where your cells knit together, arrive at some originary moment where the first inklings of what you might become, the joint of a finger, a strand of hair, was being borne. This is what our touching might allow, and for a few very cold weeks in Brussels it did, until it was time for me to go back home again, having experienced the terror and loneliness and high altitude mind merge that real sex allows. I lived there with Srin and her little girl, Tanya, who looked like the Russian doll version of Srin, like if you stuck her under a shrink ray her little girl would be left standing there, which was unnerving to say the least. Srin was working and a single mother, friendless in this grave new city built from Congo gold and dismembered slaves, living right up against the edge of her abilities, terminally stressed, just getting by on the money front which meant she was mostly broke. When Tanya went off on one of her eight year old tantrums it was usually enough to crank Srin off her thin edge. The ensuing explosion was a wonder to behold, a full on attack with a voice dripping hate you could hear from the far end of the block, no matter if we were in the middle of a supermarket line-up, waiting for the tram WHAM POW she’d go off, flaming that little girl until there weren’t ashes to be stirred. I was terrified of course, had been the subject of just this kind of weather growing up, but was fascinated to watch young Tanya’s face while her mother slammed. She never looked scared (that was left for me) or defiant or angry, in fact, her face quickly settled into a mask of non-expression, a hard, shiny object that all the heat in the world couldn’t warm. She would always look off her mother’s face at some terminal point in the distance, and hold her stare until Srin ran out of gas, and then Tanya would fast talk about something else, anything else using her best I’m-a-little-girl voice. As if this anger, this torment could not be going on. What I was watching was Tanya forgetting this moment, even as it was happening to her. She was trying to keep the rage from becoming part of her, though she was already capable of an impressive fireworks display of her own. Though most of her was wedged up against her own experience, committed to saying no, not that, that could never have happened to me.

Denial, repression, splitting. These are all familiar companions to plagues the world over.

Thomas Köner or The Music of AIDS

I never met him. He was sitting, all six feet and more of him in a chair looking like he’d just come off the football pitch after a too satisfying round of headers, not larger than life, no, but seeming larger in that moment than the dark isolationist drones that he’d been resodding Europe with for the past decade and a half. I was too much in the thrall of him, waiting for his concert to begin, to up and introduce, not this overmind of computer electronica, so I sat there trying not to stare at the broad back remembering Roland’s cautionary wave, “No more heroes Mike. Just because someone can turn the unheard world into music…” Roland leaves the rest unspoken. He might have added: hit baseballs, swing sticks, throw balls, write melodies irresistible to anyone under the age of twenty. There are certain moments of the flesh which still belongs to the coliseum, to bloodlust and the appetite summoned only in crowds. The music man sitting in front of me is one of their number, modest despite his proportions, a free jazz saxophonist who worked his riffs up into Dutch radio before he got tired of so many notes. He started working for Paiste, the drum factory that ran across borders, there wasn’t a skinhead who hadn’t seen Keith Moon blow up his kit night after night that didn’t want to bumrush the show and run off home with a set of Paistes under each arm. They were the grail of serious drummers and Thomas Köner, he can named at last, the Aryan giant seated across from me, Köner became a sales rep for these gongs which seems, in retrospect, a coincidence too fantastic to swallow but he swears it’s true. They said of Andy Warhol that he was someone to whom life just happened, but Köner works the other side of the street, passing so slowly it doesn’t seem like he’s moving at all, not until he’s actually arrived, and there is no moment of his life, no incidental job or conversation or sexual act which has not become, sometimes days or weeks or years later, the most perfect kind of music.

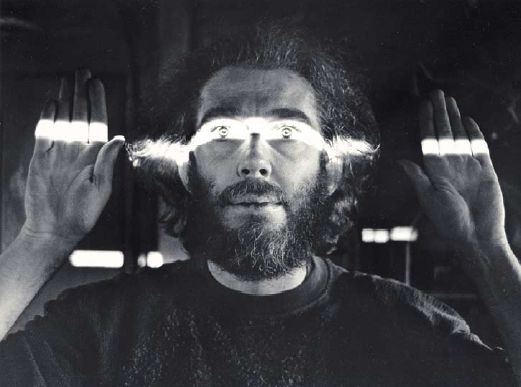

While he is flogging Paiste Thomas began recording, assembling an archive of cymbals rubbed slowly with rubber balls, contact mics catching sounds not quite audible, microscopic aftertones he would layer up later, building long waves of sound that you wouldn’t hear so much as have them settle in place of your spine, retuning the world around this dark, still center.

He liked to holiday in the north of Finland, as far away from everyone as he could get, people seemed an unavoidable part of work and its routines. He always arrived in the rainy season, a calm drizzle running through the heavy air, this is what he dreamed of all year, walking those Finnish hills that would fall away only to reveal another hill, and then another just the same. No horizon, only clouds, low shifting and pressing earthwards, you were always inside the weather he said once, a thousand years ago. Inside the gray damp pour which might at last arrest the inner monologue we use to hook the world to our personality.

To hear Thomas narrate his vacations (and believe me I never have) is to arrive at an exact portrayal of his music. Words where none belong. Descriptions of plague.

His first CD Nunatak Gongamour (amour=to love, gong=drum) laid out on Roland’s home-made Barooni label, was a fledgling effort, still hanging onto his sax, although its shiny valves featured now as a reworked bass drone, nothing Parker or Coltrane might ever call home, but you can hear it in the grooves, he’s not quite there yet, the train’s still coming in. He teamed up with Roland again for Teimo where his Paistie drones took flight. Thomas loved the names of glaciers, abandoned Finnish settlements, maps of explorers condemned to the trials of sight, busy making a private cartography of their own flesh, the density of tissue and ligament and bone relearned in places no one had ever dared encounter. It is a place, simply put, where the merely human does not quite belong. A place Thomas thinks of as home.

I caught myself looking at shoes in a shop window. I thought of going in and buying a pair, but stopped myself. The shoes I am wearing at the moment should be sufficient to walk me out of life. (Blue by Derek Jarman)

Thomas passed through the wall with Teimo, not just reaching across so he could bring back a taste from the other side, but stepping fully into it. This was art that had to be lived before it could be imagined, and he went to live there now, thick, sub-sub-bass chords layered and then layered again, and somehow in the illuminating gas that was past lonely he could work up a drenching, nearly heart-breaking emotion that belonged to anyone with ears enough to hear it. Teimo was an unexpected hit on Roland’s micro-label, widely reviewed, selling over 2000 copies, and then there were concerts, gigs in Japan and Australia and another pair of isolationist masterpieces (a word, like many others, that Thomas can’t abide) on Barooni that would cement his reputation: Permafrost and Aubrite.

Thomas finally met Yann Beauvais at a festival in Antwerp (was it?), somewhere in the early 90s, when he was loading up pictures made by fellow German arbeiter Jurgen Reble. Jurgen was the magic man of chemistry, working the image side of the room with slowly moving pictures, processed in a brew of chemicals that raised pictures to life while Köner put his basslines through the heavy juice, recording bits of the room and sending it back through frequencies only he could hear, though we could all feel them. And no one felt them more than Yann who was bold enough to ask, even then, if he and Thomas might preside over their own marriage of pictures and sounds, but Thomas could only say, “Not yet.” A polite way of saying never? But the moments grew, nothing with Köner is fast okay, not yes or no for sure, and squatting over dinner at Yann’s one Paris evening in the mid-90s Yann asked again, and was surprised to hear Thomas say that he too wondered when the two of them might. In Reble, Thomas had found a partner in crime, both romantic artistes in the classical mode building transcendental somethings through abstraction. Repetition. Contemplation. Repetition. A vast slow build. Yann’s work offered a change of pace, if Jurgen was a rock, Yann was a mosquito, the meaning right up in front of your face, and with Tu, Sempré, at last, there were words and politics. Politics for the ice man.

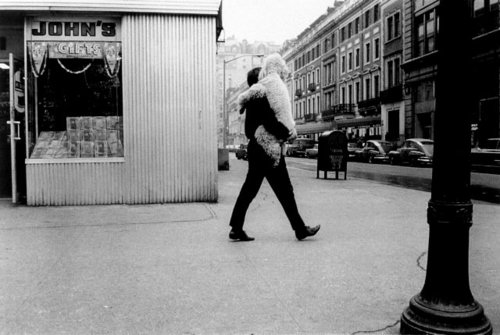

“While working on Des Rives, our first performance, I invited Thomas to New York where I’d lived for periods during the 80s. I took him to places that were special to me, though they weren’t included in the film. There he could find some of my mental sonic landscape, like the revolving hotel doors which divided sounds of the street. As we walked I told him stories, about the coldest winter of 1976 for instance. I was coming out of the subway looking for Rafik when I saw a man lying on the pavement. It took me awhile to catch the blood around him, and then the police kneeling over his face, and I realized he’d been shot. The first dead man I’d ever encountered.” (YB)

Together they would try to conjure the sounds of the plague, lift some private sorrow into the sonorities of word and musical event, pitched so that hearts might open while hearing it, and without end. Yann called this work Tu, Sempré (Always You).

Cocktails in Amsterdam

It’s 7:30 in the morning here, an hour past midnight in the city I used to call home, a cold fog reaching up over the red bricked roofs making its inhabitants suddenly and wonderfully invisible to each other. A library hush accompanies, everyone careful not to break the spell that seems to summon each new bricked canal for their pleasure alone, every citizen a metropolis. I am sitting with Jankees, who has grown tired of the long distance swimming that took hold of him at an age when most serious swimmers had settled into retirement. He prefers movies now, all those hours in the water have given him a feel for doubles, mirrors, reflections of every kind.

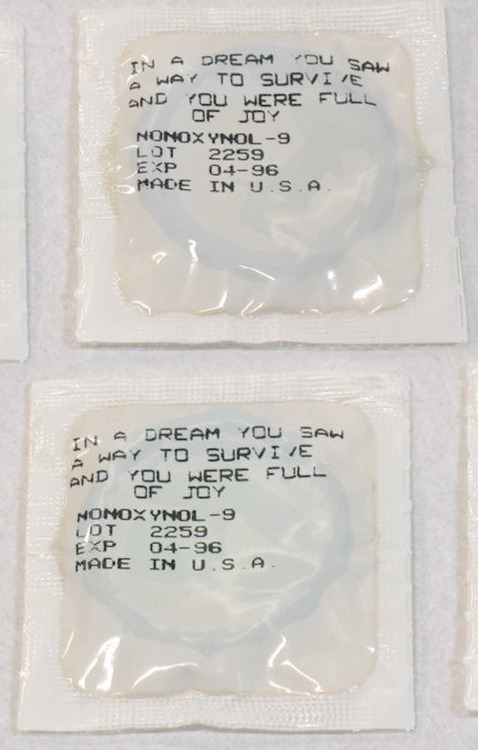

In a hurried moment I’d forgotten to pack my HIV meds in the onflight bags, and scurry through uniforms of the new Europe, the new personality that waits for me here, feeling for the crisp plastic screw tops buried deep in my luggage, more responsible than any act of will or prayer for keeping me alive. The cocktail they call it back home, a word I associate with the Dick Van Dyke show, balm of the North American preteen. While the longhairs were Woodstocking we were swallowing the old dreams on black and white television, watching Rob reach for his evening martini. Of course he worked as a comedy writer, what else amidst this barely contained topos of fear, every surface of his showroom apartment crammed with a brave new American manufacture, fridges and stoves thrown into the breach of empire. They, the enemy, the Communists and anarchists, the queers and niggers and Indians waited on every corner to take back what had once belonged to them (“As if!” Rob thinks). These white appliance stopgaps accumulate like treasures in the Vatican, in upwardly mobile split-levels like Rob and Laura’s. At night, when he gets home to his perfect wife and TV dinner (if only they could stop showing us the Vietnam war! These images of empire upset the digestion) he lounges in a chair large enough for three Robs, and reaches for his cocktail, unshaken, unstirred, and surveys the kingdom of his living room, a territory which he knows that soon (Will I get that raise? That longed-for promotion?) will be expanding, absorbing others of its kind. He’s an American after all, he’s been promised from birth.

I am shuffling through my bags searching for my cocktail thinking of Rob and Laura when a grizzled survivor from the next table begins to speak (To us? Is he speaking to us?) in a desperanto mix of Dutch and English and some sub-German dialect. He is making a speech in fact, though we are the only ones near enough to hear it, and as I pop my pills his eyes go wide and he shouts, “Juden,” while running his hand over his throat. Jankees wants to leave RIGHT NOW but I’m tired, my motors aren’t running yet and besides, I haven’t finished my sandwich. I walk on over to him and give him my best threatening made-in-Canada staredown, which looks more like an apology if you want to know the truth. I come from a culture of apology, while the Americans have made a public imaginary out of success, the will to power, we in Canada have practiced an art of failure, rubbed it smooth until we could practice it with élan and grace. We have succeeded in making a culture of failure and apology, so my stony look glances off him no problem. He shouts back at me then, “Juden! We should have killed you all. You are bringing plague to our land.” Because I’ve stepped off the plane hardly myself, I push my face into his and hurl a string of invectives (sadly, these remain the only Dutch words I’ve managed to retain). He leaves then, dissolving into the mist, another ghost of the old world biding his time until his hour will round again, some ancient memory of fear waiting for the radio, the loudspeaker, the TV, to begin the revolution, the purgings and rituals of exclusions, the bloodletting of the righteous. There are graves to be spat on. Museums which must be marked or bombed. The dead must never rest.

The most chilling word he offers of course is we. We should have killed you all. As if it were me too, waiting with the hatred in my mouth, my own killer. As if I’d marched alongside him looking for enemies and finding them everywhere. And then each other. And then me.

Of course he knew, didn’t he, instantly, just what my medicine was for, which meant that either he himself was similarly afflicted, or he knew someone who was. Unusually, I’m able to pull out my Norvir just about anywhere. Because I have to take it with meals I carry a bottle of the bright orange liquid into restaurants and cafes and bars, and no one looks up, no one notices at all, and I wonder if I’m just the same, these small signifiers of the end multiplying all around me, though without the code they appear as benign moments of the cityscape, passing shadows, unnoticed. Of course people are dying in front of me all the time, I just don’t see them. I won’t see them. Not me, never me, no.

Amsterdam Redux

I have been invited to Amsterdam to share the long moments alone in the edit room from the past couple of decades. Retrospectives are usually reserved for the dead, but this one attracts so few people (who exactly did I have in mind when I named one of the programs, ‘The Agony of Arousal’?) that I am weightless, an astronaut bounding over these strange new equators of the past. It was a long march alright, but mostly just for me, those old bruised pictures raised to light, some of which, mercifully, would be heading straight for the dumpster as soon as I got home. The last screening contains my most recent and personal work. Naturally, it is about AIDS. When the lights come up, when I have watched my friends die again, the way only someone in a film can die, over and over, and without end, I am moved, a little choked as I stand up in front of the handful, so I’m not prepared for the first question. My interrogator has one of those long, thin faces they manufacture in a plant just north of the city. They give them away for free so everybody has one, faces which seem to drip from their foreheads and stitched across it, almost carelessly, a pair of slave trader lips and glasses so beautiful you could make a down payment on a house with them. Serious. He has a serious face. This serious face asks me, “Why did you bring those movies here? We don’t have a problem with AIDS in Amsterdam. It’s only the junkies who become positive,” he insists, pausing to look around the room, “and the junkies haven’t come.”

There is a moment in Letters From Home when Sally says, “Twenty more people will die of AIDS while you’ve been watching this film.” But because it was made in 1996 that no longer holds. Now the number is more like thirty. But of course these people are dying in Africa and Asia, that’s what the man with the dripping, serious face is telling me. It’s them over there, not here, not now, no never not me.

Besides, I have committed the worst sin a filmer can make in these fringe venues. I have bored the audience, dulled and deadened them. Now it is their turn to tell me how much. If this is all feeling a bit off the beam, it’s because I’d spoken to Martel the day before, a stranger OK, we never met in the end. He worked as a journalist for the national daily and had been sitting on a mound of my tapes for the better part of a month, ready at last to squeeze his musings into soundbyte infotainment Dutch so his readers, maestros of Matrix-land and other moments of LA manufacture, might glimpse some far shore of cinema between his homilies. Only he can’t do it. He is at home when the call comes, it’s his doctor, the tests have come back and would he mind coming in? No, better make it today. When he arrives he hears the words he’d been dreading these too long years, lost in the arms of the anonymous, his once lover already dead but that was already four, five summers ago, when something steady flickered up into his life at last, at fucking long last and then that was gone too. There were others but never for long, not too long now, they would start getting too close and he couldn’t help it, he could feel himself letting them go, just couldn’t face all that again, not yet. And now the doctor is telling him, “I’m sorry. You’re HIV positive.”

He calls me later that day, with a small, thin voice sounding far away from me, his body, the body of friends and family. It is a voice sounding from some long ago recess of his mother, the plains of Sinai, the Uldivai Gorge, he is calling from a thousand years ago so it’s no wonder I can hardly hear him saying, “I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.” And then just, “I can’t.” Over and over. He echoes the doctor’s words, he can’t help it, he hears them pounding away inside in place of his heartbeat, “I’m sorry,” he says, “I just can’t do anything for you. My doctor told me that I’m…” Only he can’t bring himself to say the word, not today, not with the fresh kill still lingering in his mouth. That comes a few days later, when we talk and talk and talk, he doesn’t want to meet, no way, doesn’t trust himself to leave the apartment, he knows what’s out there now, how many kinds of misery the body can conjure. But he delivers the news and many other things besides which I can’t repeat for you here. But it’s his voice I hear ringing clear through the room when the man with the serious face tells me that I’ve come to the wrong place, we don’t have an AIDS problem here. Now take your avant movies and leave please, when we want some more propaganda we’ll just turn on the TV.

Walter Blumenthal

“In August 1942 the Gestapo arrested Walter and his wife Elisabeth in their apartment in Berlin-Charlottenburg. They were to be taken away in a lorry. Shortly before it left, something was thrown from the vehicle. A neighbor saw this and later picked up the object. It was Walter’s wallet, containing his business card and two photos. Walter and Elisabeth, both in their seventies, were deported to Thereslenstadt and later murdered in Minsk. Time and again the family of the neighbor who found the wallet told its story, preserving the memory of the Blumenthals and their fate.” (Jewish Museum, Berlin)

Pip’s Story

Robert decides to go to Portugal, it’s not unusual, the Europeans are always leaving, turning the corner, opening the next door. From his friends he gathers a list of forty places he has to visit, no doubt about it, he’s going to be busy there. He’s young, not yet thirty, but one of those born into a sense of duty, he entered this world the way others enter a monastery, there is work to be done, so he crosses the border with his steering wheel in his right hand, and diligence in the other. He visits two, sometimes three places a day, never straying from his list, precious list, and at night he settles the car by the roadside, or sometimes in a park or school, and goes to sleep. He doesn’t have money for hotels, but he eats well, fish mostly, it’s the season, and those glazed palmiéres for desert, a little heartier than their Paris cousins, pastry fans made in layers which come apart in his fingers. The floor of the car is covered in them.

One night he has trouble finding a place to sleep. The streets are too narrow to park in, the schools are locked or closed, and he finds himself driving on past the outskirts of Vila do Condé. There’s a large road running to Porto and he pulls off the shoulder hoping to stay there, right there, but when he looks out there’s nothing, not a tree, a post, a bench, nothing. It’s like someone’s taken an eraser to this part of this world. So he keeps driving though very slowly, because no matter how he turns, or how far he ventures across this road, which is not a road anymore but a path of dirt and small stones, he can’t make out a thing. Finally he decides to stop, he wants to get out and take a look around, so he leaves the headlights on. He opens the car door, steps away from the hood, and very nearly slips and falls. He is parked five feet away from a sudden drop. The land ends here, while beneath him the river is flowing. Waiting for travelers.

The moment I keep rubbing in Robert’s story is when he decides to stop the car. Of course it’s luck, pure chance, but couldn’t we also see this as an instant of knowing? Imagine a school, a university where students would learn to recognize, organize, even attract moments like these. I believe that such a school exists, though there is no one paid to explain the way, no curriculum, and above all no rules. I believe that this is the place which art inhabits, though most of its practitioners would gape at the mention. I know, I know there is little evidence of this kind of risk, perhaps this is why most shows are dull affairs celebrating the narcissism of objects (Look at me! At me!). The drivers of these cars have pulled over long before the abyss, they have planned their routes well, they are efficient, workmanlike, organized. But the art I long for, the hope I carry each time I cross the threshold of the gallery, museum, cinema, is that I will find someone living outside the code, who has left the known world behind, willing to risk everything for some moment of seeing, where the body can show itself again, radiant in its new understanding.

When he stopped the car Robert was still too young to believe in accidents, surrounded by nothing at all, his body reached out and saw his own death, and ordered him to stop. If you met Robert you’d understand right away how he managed to do this, because Robert is someone who is always in love, not with Sam or Julie or José just in love, just like that, opening. Robert is always opening, and when we meet I wonder how he manages, he looks like he’d bruise so easily. It’s something like a challenge, like he’s laid down a glove between the two of us, the soft face asking: will you join me here, in this place, opening and then opening again. And without end.

Yann’s movies

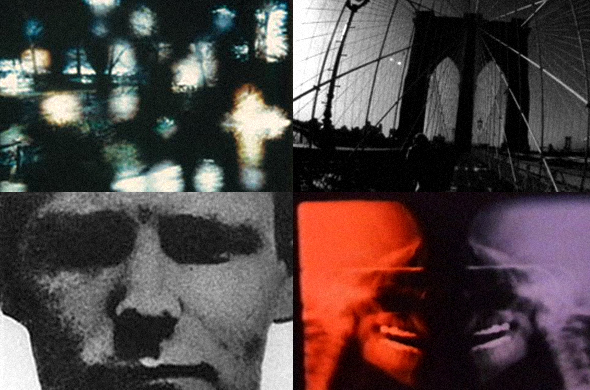

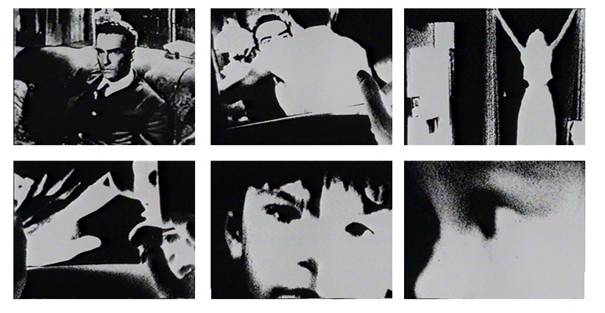

Yann’s first movie is entitled R (5 minutes 1976). He ventured to an empty field and shot it like a Bach fugue one afternoon, flicking his glass eye over the tall grass once, twice, three times, then zooming in and flicking again, easing matters with a real time pan then back to a staccato single frame eruption, breaking up the landscape until it appears as if it’s looking at itself. What Yann’s insistent flicker reminds us, is that this is a reproduction, the natural world has vanished behind the curtain of science. There is no there there. When he tells me he made it all in-camera, I can hardly believe him, it appears the result of patient hours of rephotography, smoothing the moments, the repetitions, the glissando glides of black and white flickering across this root life. It is a film I tried to make once and failed, no not just once, but three times, in each instance getting as far as the lab door before realizing no, this would never do, it’s not ready yet, and it never was.

Unexpectedly R became a hit, or at least a thud, which is max impact in the fringe microverse. It established him instantly as a force to be reckoned with, prints were purchased and circulated, he was an artist after all. Yann feels that all films are not created equally, that democracy has little place in the production of pictures. “In your life you may produce only three or four films that are of any consequence,” he tells me, “perhaps only one. The rest are beginnings, pointers, preludes.” He wonders if he has already filled his quota. Somehow none of this seems to bother him, tug at him, the way it pulls at me, almost all the time. I obsess about Yes, the teen idol band whose symphonic rockalots washed over my mescalined ears again and again. They were capable of three perfect records and a live set that made me weep to hear it. Then followed a double LP of such bloated self importance even the band turned against it. Subsequent efforts proved little more than technical exercises (so many notes, so little feeling), each new record seemed haunted by the group’s understanding they’d lost touch with the manna they used to call home, the old numbers dutifully trotted out as concert encores, but when they reached for it now it was gone. They put out record after record, the line-ups changing as one member after another quit in frustration, all consummate musicians at the top of their game, unable to summon again the big feeling they had in those few short years. When I talk to Steve Reinke about this he figures that an artist has about a decade, more or less, to make their best work in, the rest is rise and fall. Hopefully, Steve winks at me, no one else notices. I had imagined matters would be different here on the fringe, no one looking over our shoulders for the next big thing, there was simply no place to aspire to that might bend the relation between the movie that wanted to be made and its maker. But Yann assures me it isn’t so, and after watching the sub-optimal efforts of fringe makers in fests around the world I can only concur. The muse is a temporary diversion.

Yann didn’t stop with R, though it would haunt him in the years to come. He was competing with himself, though when he began he didn’t know there was a race on. Each year brought another film, or two, until he had a body of work, by the turn of the century there were thirty, fourty films, a trail of emulsion hinting at the secret pleasures celebrated by all those who had made an adventure out of seeing. There was Amorosa (14 minutes 1983-6), a flickering travelogue with young Miles seen through rosy glasses, and while its midsection boasts a bravura fountain edit that would make Kenneth Anger blush, it’s simply too long, too many vistas which flatten as the relentless pace continues until everything looks just the same. There is Divers-Épars (12 minutes 1987) and Spetsai (15 minutes 1989), flickering chase films which grab at the world in small bites, nothing lasts, no not for more than the time it takes to say ‘There,’ and ‘There’ and ‘There,’ one scene replacing the next in rapid fire succession. These are chase films, only the haunted one, the lonely pursued figure is never seen. The filmmaker Yann. After a lifetime of childhood illnesses and fever he learned to push himself until he was too tired to go on, then he would push himself some more. For years he has lived on the verge of collapse, seeing too much, living a little too much, and the moment before falling, when the white light edges off the corner of the eye frame, is an experience he returns to in film after film. He is condemned to it somehow, it’s how he sees, so when he picks up the camera there it is again.

In the early 90s he began the first of what would be a trio of films about AIDS. The first, SID-A-IDS (5.5 minutes 1992), was made in conjunction with Positiv, a Paris-based AIDS joint that grew alongside ACT UP. (“My good friend began Positiv so that’s where I went,” says Yann, shrugging.) Yann offered to commission a series of shorts around AIDS which he would tour through France, a difficult promise to keep as it turned out, because “art and politics don’t mix in Paris.” (Later, when his film was purchased by ARTE, he gave the money to ACT UP.)

Still Life (12 minutes 1997) features a cascade of words, a rainbow flicker shattering its procession of titles into quick, outraged phrases. This is Yann’s J’accuse. Three voice-overs cycle through the speakers, Derek Jarman’s pill regimen from Blue, David Wojnorowicz’s recount of a friend’s last hours and Yann’s confessional. This is a formalist’s politic, an image made of words: “15 years of the epidemic in France. 45,000 dead. Everything is OK!”

The consolation of making movies

While my friend died I…

While I watched him die I…

After I left the funeral I…

Paris: Black and Blue

I never manage to arrive in a city, no matter how long I stay, the frame it provides for its inhabitants remains a blur. Paris, for instance, never brings the Marais hipsters into focus, the hustlers circling the Bastille, waiting for a look on a stranger’s face that will admit them into anonymous worlds of pleasure (and pain of course, in a city this beautiful, this old, pain is never far). Instead, Paris is a face, Yann’s face, his too-blue eyes opening the moment between us, shining with the luster of a childhood he refuses to leave behind. But while they are softly singing of the now, right here and now babe, they are also lost somewhere. While Yann speaks of censorship problems, lobbying the museum, health care for immigrants, his eyes are wandering through the windows, up over all the walls and outside, lifting, always lifting to the stars he knows are there, even under these small roofs, the impossible miniature of his apartment. When I speak to Yann I can’t help thinking: heaven is not so far, after all.

When we alight at Orly, after a three hour flight where the blonde flight attendant (do they only come in blonde?) can’t stop smiling, putting everyone on edge (is the joke on us?) I’m lost straight away, so even though I know it will cost me a good part of my screening fee, I climb into a cab. I take out the camera and pull my arm into focus, hanging off the thirty degree windows, still steaming from the day’s oven, watch the light play across my fingers, the background coursing past, my body shaped and reshaped in the French ozone holes. We rush together along the highway, there’s no room for fucking around here, the cars so close I can count the hairs on the back of the neck of our neighbor. The driver plays jazz, what else, but I jump from the seat when he starts to sing along to Armstrong’s Black and Blue, the angriest cut of the great entertainer, the one who kept walking in the back door and raving up the joint then leaving when the show was over. “Oh sorry ma’am, I better not have that drink, thanks for asking,” knowing that black and white cocktails didn’t mix in these small minds, so he left the same way the cleaners and busboys did, heading for the coloureds only hotel. He just kept smiling, and shrugging and laughing, certain that it would turn out alright, and some nights it did, but the long years of nigger and boy and sniggering pale trash that weren’t fit to wipe his horn worked its way up into Black and Blue, only he sang it so sweet and sad they couldn’t help playing it on the radio, even today, and whenever they did, you couldn’t help singing right along with him.

How will it end?

Ain’t got a friend.

My only sin

Is in my skin.

What did I do?

To be so black and blue.

(Black and Blue by A. Razaf, T. Waller, H. Brooks)

Up ahead a bus stops and the driver, the little tag on the back of his head says his name is Gus, rolls his eyes at me before remembering I’m anglais, complicated matters like traffic are doubtless beyond my understanding, so he turns back to face them and so do I. The first woman off is a great round ball of a tourist and she is followed, more slowly than surely, by a tribe of others, each wearing the same incredible t-shirt, dark cotton strained by too many creme brulées and the long miles of bus. There is a simple message sprayed across their collective chest, loosed at last onto the baking cobblestones. “I’m Real.” No wonder they’re smiling.

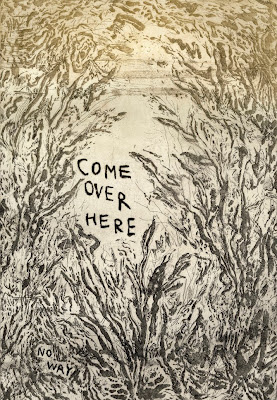

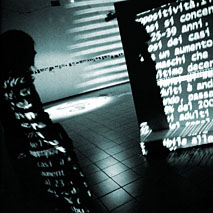

When I arrive at his apartment, Yann shows me his new movie, Tu, Sempré, a political film thank you very much, with a capitol P. He has grown tired of the emulsion benders, the many still exploring the material roots of cinema. How does it work? What happens when you take just this one moment, say a zoom or pan or even flickering coloured light, and let that become the movie? For both of us this used to be home, but we don’t have much feeling for home left in us, not after burying the ones that lived there with us.

My body feels like a third person in the room, my mind a second person, my friend a first person, the doctor absolutely necessary. (Tu Sempré)

There are texts flowing, crawling, moving through the frame. Confessions, statistics, commentaries, notes in the margins running, always running and it is too much, it appears as compulsion, hysteria even, all these words in a place usually reserved for pictures. I can’t help but wonder if Yann has come to end of his pictures, or found himself in a place where pictures are no longer enough, unable to bear the burden of all that needs to be shown and shared. Between the words there are moments of flesh, glimpsed in close-up, the camera crawling through the pores, but just for an instant, just long enough to remind us that these words, this movie, has come from a body, and is returning to it.

At that point when I first began to comprehend the enormity of what was happening to my community, I understood only that we would lose many people. But I did not anticipate that those of us who remain, that is to say, those of us who will continue to lose and lose, would also lose our ability to fully mourn. I feel that I have been dehumanized by the sheer quantity of death, so that now I can no longer fully grieve each person—how much I love each one and how much I miss each one. (Tu Sempré)

In place of a single viewpoint, the portal of imperative that movie talk usually offers (Do you love me?), there is only diffusion, a scattering of words. They appear at once streaming in opposite directions, spoken in voice-over, asking, language always asks us to listen (Do you love me?) insisting the viewer/listener make a choice. Which path to follow? And how far? For each member of the audience, a different movie. And in place of the pictures which have been denied us, we are forced to summon our own.

Along with the common celebration of the unbounded flows in our new global village, one can still sense an anxiety about increased contact and a certain nostalgia for colonialist hygiene. The dark side of the consciousness of globalization is the fear of contagion. If we break down global boundaries and open universal contact in our global village, how will we prevent the spread of disease and corruption? This anxiety is most clearly revealed with respect to the AIDS pandemic. The lightning speed of the spreads of AIDS in the Americas, Europe, Africa and Asia demonstrates the new dangers of global contagion. As AIDS has been recognized first as a disease and then as a global pandemic, there have developed maps of its sources—a spread that often focuses on central Africa and Haiti, in terms reminiscent of the colonialist imaginary: unrestrained sexuality, moral corruption, and lack of hygiene. Indeed, the dominant discourse of AIDS prevention have all been about hygiene. We must avoid contact and use protection. (Tu Sempré)

A confession. Seeded along these two texts are words of my own, Yann had asked me for them how long ago now, a year, or two at least, and after I scribbled them into the computer and sent them off he had one further request, that I record them as well. I remember standing at the microphone at the beginning of the session with Terry, the kind engineer who pretties up rock bands most days but loves the lyrics most of all. It’s what keeps him hanging in there hour after hour, listening to the same dull tunes wearing grooves into the imagination. But he lives for a well turned phrase, so he never minds when I book an hour because at last there are only words, precious words now, no Chuck Berry reworkings in sight. I start by saying hi to Yann and Thomas, feeling like a ghost, like I’m leaving something behind which I won’t be around to see later.

These words. This testament.

There is no speaking without a return address, my words find their way back on a silver disc Yann posts from Paris. On its smooth surface, an accretion of nullpoints and ones, digital evidence of the cross talk between Yann and Thomas. The soundtrack has arrived.

It is strange, uncanny even to hear my voice gathered up into the storm of Thomas Koner’s plague. He makes me remember. There are so many sounds that have passed through my life, and lacking the means to describe them they slip right on by, there’s nothing for them to hold onto. My memory begins with the eyes (Was the day bright or dark? Not: was the day loud or quiet) and to an unfortunate degree, stays there. What Thomas summons (how did he know?) on this disc is a micro-memory of sound, not deja vu but deja écoute, the thousand small ways the body is defeated, unable to get up off the floor, breathe clearly, see across the room, and then something like hope, the beginning of hope arises out of these congested tones as the cells begin their patient work of restitching, climbing the mountain of the next day, leaving fever behind. There is no final clearing here, but the work, which I need hasten to mention does not belong entirely in Thomas’s laptop but in this place of trust grown slowly between Yann and Thomas, is gobbed up into narrative form, telling tales of a (social) body’s passage through plague. How could I fail to hear it as my own story, granted chords and micro-tonal murmurings, even as Yann’s voice, crisp, deadly, precise, delivers fragments from the front lines of this illness, giving way at last to Greg Bordowitz raising the roof at an AIDS rally. The hairs on my arms are standing. For three months nothing else will do, it accompanies breakfast, email, everything but the edit room. Digital narcissism? Or some way to feel, with Rimbaud, with all of those similarly afflicted: Je est un autre. But also: we are not alone. Someone has learned our song, someone from the outside, and we can sing it along with him. This plague will not be the end of us after all. This song, this movie will continue after we have cum and gone. Hear it if you can.

Always You (Tu Sempré)

They told me it wouldn’t last, that I wouldn’t live, that there was nothing they could do for me. The year is 1988 and I have AIDS, and there’s nothing, not really, that anyone can do about it, except to monitor my decline, along with all the others, weak and weaker, all waiting to hear what we already know. It’s worse now, we didn’t think it could get any worse but now it’s worse. When we leave there will be funerals to attend and friends to visit. New ways to say good-bye.

There are fevers and bad glands and pneumonia of course and bad reactions to drugs and shingles and nerve problems and I keep thinking I’m one of the lucky ones. Because I’m still here. Still alive. Slowly, while my friends are lowered into the ground, or burned, or tossed across the water, or scattered across parks and street corners they used to brighten, slowly these new drugs arrive. Where once there was certain death, now there was a reprieve, for some of us at least, for many it was already too late. For anyone who was unlucky enough to be born wherever health care was impossible, in the epicenter of the disease, in Asia and Africa, the drug companies just said no, you can’t afford it, you can’t afford to live, and we can’t afford to make you live. But I won the lottery again, I get health care just because I was born in this country, this Canada, this Canada of the body. So I take the drugs, even though they make me sick, sicker than I’ve been for a long time, but I get over that. I get well again, and then something like normal happens. For a while it’s manageable and there’s not a funeral every week anymore, now it’s every month, or every two months and all around me people are beginning to feel again. We’re letting ourselves feel again. Because that’s possible now, and it hasn’t been possible for a long time.

When I talk to my friend Gene he says I like bareback riding I don’t care, if I get a dose I’ll just go on the pills, just like you Mike, and I try to tell him but it’s no use. He’s going to do it anyway, and there’s nothing I can say that might protect him from himself. There is only now. That’s what Gene is telling me. Only now seems like such a short time.

My friend Tom is dying of Parkinson’s. Slowly, he is losing control of his body, fired from work, his bank account empties, and it’s not like he doesn’t care, not at all, but he starts having sex at the clubs. Sure he tries to check for condoms but sometimes it’s late, he’s not always careful, and eventually, finally, he becomes positive too.

We are snatching defeat from the jaws of victory.

I’m so tired of dying. I know my friends are tired of it. The late night calls, the vigil in the hospital—for what? I’m still here aren’t I? Just like the epidemic. Just like AIDS. How is it that a disease which is so easy to stop, so easy not to pass along, keeps getting passed along? Is this love? Is this what love’s become? Whoops, I’m sorry honey, I think I just killed you. By mistake. It’s all been a big mistake. Only there’ll be no cleaning up the mess, not until the last one of us is dead and gone, no longer even able to utter a name, a single name of the long roll call of all those of us who have knelt beneath this illness, this reliable companion, and looked it straight in the face and said yes. Kill me. Infect me. I’m ready now. Ready for the end. Won’t you join us here? It doesn’t take much, just a moment that’s all, a little slip, and you’ll be on our side and then you won’t have to read about it in the papers anymore and wonder why because you’ll be in it, body and soul. Like us. You’ll be getting busy dying to live.

Originally published in: “Yann Beauvais: Tu, Sempré #5” (Exhibition Catalogue) L’Espace Multimedia Gantner, Paris, 2003.

Showing Pictures: a conversation with Yann Beauvais and Mike Hoolboom

Mike: The question of distribution pricks me at the moment, perhaps because my work is shown either to specialists who have already seen it all, or to the absolutely uninitiated, like the high schoolers in Guadalajara who were forced to endure their first ever documentary movie in a vast assembly room better suited to the speeches of bleeding virgins than my fragmented corpses. At least they had the company of their cell phones to warm them when the montage refused to settle into a reliable three act structure, unlike their daily conversations, their busy fingers tapping out the harmonies of major chord delights and narrative closures.

It seems to me that fringe media distribution has defaulted into two primary modes, in art galleries and in festivals. How many times did artists at the recent Rencontres Festival in your beloved city stand to announce that the movie we were about to see was “really” an installation, but was showing here as a “single channel” movie. Well, as a movie after all, shorn of ambient light and visitors shuffling between rooms and yes, the ringing of cell phones. Reluctantly, they seemed to announce, their work which seemed to my old fashioned receptors to be movies, had been returned to the movie theatre.

The reason that festivals do not bring me happiness is because they stink of the mall. There are too many pictures shown all at once, one after another, all howling for attention like the Bargain Prices Reduced No Offer Too Low signs which greet me in the covered bins of the no-frills shopping paradise. Is it only me? I find it hard to separate one illuminated hope from another, they all blend and jam and mix, after a single short program I am already confused, and then there is another and then another. And afterwards, perhaps it is the shallow company I seek in respite, but no one speaks about the movies, or only in the most cursory of terms. I liked it, I hated it, it was boring. Yes, surrounded by artists at the festival bar I am returned to the mall. I’ll take it, I love it, where’s the food court? I want it or I don’t. I must have it or I never want to see it again. And running through it all is the heady aroma of forgetting, which I embrace like the good North American that I am, and which I find amply demonstrated by every festival I have ever visited. What I am watching is less a procession of pictures and sounds, but the vapour trail of their disappearance, as they make their way across a crowded theatre, or a not-so-crowded theatre, or the shop window of the internet café that resides in the “festival neighborhood,” or the bar which dishes drinks next door to the festival headquarters. Yes, there are pictures playing everywhere, and just like in the mall the more I see the less that manages to stick to me. What’s your name again?

Each program runs only once, each sliver of light appears and then will never be shown in that city again. We’ve had it, we’ve had enough, it’s old news, soiled. Once its light virginity has been stripped away please cast it out into other cities, where it can recover its lost innocence before new eyes. Yet again (and again) the bride stripped bare, even.

But there is still the possibility that from this noise some moment of cinema might arrive. The physical conditions are impeccable after all, the light cast into a darkened chamber, with real speakers and a reclining cushioned perch to absorb it all. The festival seat offers its viewer an invisible visibility, invisible exactly because these pictures appear so fleetingly, there are no reruns, no time shifted channels, no way to see it later via home video or bit torrent happiness. They appear like a series of mirages, and then are returned to the basement shelves of their makers.

On the other side of the fence are the gallery artists. Some are already kings and queens, the subject of learned treatises and awards which have turned the heads of even the most judicious of collectors. Histories have been rewritten to note their prominence of place, the Bolex winders of the past decades have been relegated to a suitably dusty and forgotten recess, while in their place march the painters and sculptors who might once have held a camera and exposed a few frames, rolled a bit of tape between performances, these are now the benchmarks of a new art, marked and remarked in handsome periodicals and coffee table companions. History is always written by the winner, and anyone who is able to follow the money may quickly enough track the rise and reign of “important” artists who have left behind those who failed to make a market impression.

This work is released in “limited editions” (just like the limited editions of 16mm prints from a generation ago – who could afford to make more than a few prints? Only now at the moment of digital proliferation, dvd bootlegs may be had for nothing at all, while signed copies can fetch enough to keep landlords from the door) and parlayed to a coterie of collectors. The newly commodified beams of light appear, unlike their festival counterpart, “all the time.” If the gallery is open that can only mean that the movies are “running,” hard at work, busily staining a bit of back wall. The gallery installation offers the possibility to its viewers that it may be encountered in a time of their own choosing, and is willing to trade for this convenience a suite of bad projectors, dismal sound, ambient light, competing soundtracks and audience chatter. Oh, and mostly they are attended by party goers at openings where no one looks at the art all.

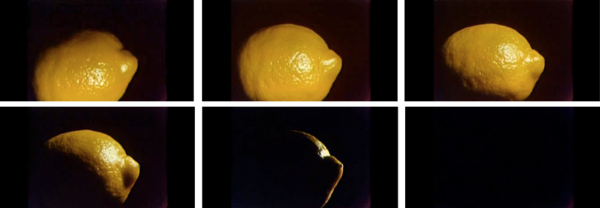

There is one experience with gallery installations that seems paradigmatic. It is a moment, no larger than that, but I imagine it narrates a summary of the field. My friend Jason is something of an audio visual masochist, so naturally enough developed an interest in the work of Hollis Frampton. When I heard that Frampton’s Lemon was showing at the newly reconstituted Museum of Modern Art in NYC, I urged a visit. Lemon is a film we had both seen, it shows the fruit in question lit from various directions against a black background, and runs for six or seven minutes. Of course it is silent. We didn’t have to go far to find our lemon at the MOMA, upon alighting on the third floor, the one dedicated to art that insists on moving, we found it right there, projected in the hallway, just outside the room which held the mysteries of Andy Warhol’s perfect face movies. Jason and I stood and watched Lemon, and then watched it again (it played on a loop, like all installations, it has no beginning or end, it is eternity itself we are glimpsing after all), and finally we watched other people not watching it. Because this is one of the most visited museums the world over, there were scores of visitors that passed us by, and for the most part no one noticed that Lemon was busily playing at all. In fact, the only indication that something art worthy might be occurring in that direction was that we were both pointing that way, but even this only gave the occasionally passenger pause.

Frampton worked in 16mm, and showed his work whenever possible, often traveling in accompaniment to lend his witty, verbose, smoke filled expositions. He really was a fabulous talker. Had someone proposed to him that his modest vegetable stand of a movie might one day be attended by hundreds of visitors each and every single day I’m sure he would have raised more than an eyebrow. This could only be science fiction of the cruelest kind. But crueler still is the fantasy of display, to imagine that anyone actually sees what is being shown in a gallery. If the festival offers an invisible visibility, the gallery, by contrast, offers a visible invisibility. Because it’s going on all the time, it turns out that it’s not really happening at all.

Yann: The questions you addressed are multiple but could be concentrated on two main ones from which others result. (Writing in English make me feels clumsier than usual!) One is about distribution, the other regards diffusion. Let’s see if these two things are related.

Today it seems that there are fewer places showing films in the manner we used to see them. Theaters devoted to experimental films have dramatically decreased. This has been accomplished with a twist, the avant-garde seems to repeat itself within exhibition (i.e. screening), offering very few locations to show works, while at the same time institutional houses, dealing with cinematographic genre and repertoire, are busy occupying this forsaken territory.

In a similar manner, festivals have capitalized for many years on this tradition of the avant-garde until recently. “Avant-garde” has become a category of programming. But one wonders if avant-garde practices are still relevant with films today. Maybe the notion of the avant-garde and the way it has frozen a practice into a genre is the main limitation to a renewal of film practices. I guess we will go back to this argument within our talk.

When and where do we look at film today? Twenty years ago it was rather easy, film were mostly seen in the theater, or within the realm of small groups sharing works with a motivation to share ideas about film or induce critical discourses. The public screening, as opposed to the private ones organized by the filmmaker, inscribed itself within the network of shows one could see or miss… It was screened once a while. You had to see it at that moment or hope there would be another screening soon, whether public or private, in order to see the work. Tapes were not readily available, and their use was scarce. If one wanted to see a film it depended mostly on the filmmaker and the theater. Festivals offered a possibility to see more films and encounter their makers in different ways.

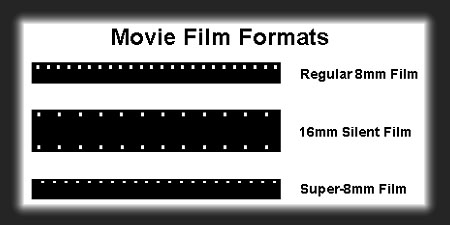

In the eighties the production of films was lower than in the seventies, except for small gauges such as super-8, which found alternative screening places such as bars and clubs, which were absolutely shocking for the “traditional avant-garde” because it meant that the use of the images was already shaken. It was as if the image cult was cut down. One was not necessarily watching a work while in a bar, so why bother showing it there? Similar questions are familiar today.

It was important at that time, and then again in the nineties, to develop visibility for work which renewed this “tradition” of the avant-garde, or experimental cinema. Part of the avant-garde was trying to offer alternatives to the limits of traditional screening schedules, and to broaden the locations for screenings. For some filmmakers the use of loops became a motive and a weapon to move against the flow of the avant-garde and its sanctified moment: the eight o’clock premiere screening. This strategy was already staged within some of the “locational” pieces of Paul Sharits.

Many filmmakers in the late eighties and mostly during the nineties shifted toward video. The economical aspect was part of that decision, but it was not always the main reason leading to that transfer. This modified both making and showing. It seemed that the question of reception was renewed with the use of another media. But was it really another media, or should we not say that it was “just” another device—like playing music with a variety of musical instruments? Acrylic painting requires different ways to deal with color and transparencies; the overall effect is distinct from oil, but one speaks of painting in both instances. Why don’t we apply this understanding to film and video?

Another thing we have to take into account is the nature of the work which is done, and by whom it is done. If the avant-garde was for many decades a western, white-male-dominated-mode, this fact has been shaken, if not yet demolished in the past two decades. It seems that the place of “avant films” is now more democratic mostly due to its makers who belong to different minorities and genders as well as races because this way to make films has spread into other countries. It is no longer the practice of the dominant; i.e. the west. Or more precisely, the dominant is no longer alone. Others have challenged it, different voices have erased the white supremacy. The amount of work has increased as a result and festivals can’t deal any longer with the production. In fact, they deal with it in a manner which denotes the impossibility of watching everything. The experience of the festival is not any longer a celebration of a common experiences where everyone shares works. No, today a festival is a micro database, a library in which one will wander according to his/her feeling, knowledge, curiosity and boredom. It marks the withdrawal of a privileged curatorial point of view, toward an agenda of multiple choices. This doesn’t mean that the festival is not going to address specific issues with thematic programs, homages or retrospective. It shows that the condition of a festival is to give access to parallel routes. A festival becomes a collection of possibilities. It is a network, a web. From this condition one can understand that a specific work becomes just another work in the flow. The sheer quantity of works already implies further screening opportunities and so questions the means of any single festival. In a festival one work follows another, this massing and the attention required to see works is (maybe) not at its best within festivals. Maybe the ways we have conceived of exhibition are obsolete, and we should think about new forms of giving access to the works.

Today, transmission does not mean theatrical screening. It encompasses broadcasting as much as downloading. One has to deal with these multiple channels of appearance of a work.

On another side of the field many filmmakers are producing installation works that have as a common denominator the fact of being projected in a white cube, three meters by four meters in a loop. But this denominator does not make of a work an installation. It reflects the tacit agreement with the dominant code of the art market of these days. The fact that the art world is looking at this type of works is positive despite the fact that often the works are not presented according to their original gauge. But here again something is happening that we can’t repudiate for a question of faithfulness. One has to think about accessibility and visibility. These works have been often seen in the private circles of the avant-garde and are now dealing on one side within the traditional avant film market, and on the other hand, the art market. In both cases the playground has changed. We are not dealing with the same territory. We have to think differently.

Mike: Yann as usual you put it so well. Though I’m sorry that you have to bend your thoughts into English, language of the new imperium. Some further thoughts on festivals: when you write that the massing of works requires a web-like attention, yes, I follow your argument. It defeats inside me the impulse to know everything, to have seen it all (the impulse which belongs to the dictator of knowledge and to the fan). Because of the rush of pictures through the projector it is only clear to me that inside the vomitorium of the fest, I am missing even what I am seeing, that I am here to celebrate not a work finally arrived at its moment of public rapture, but instead a mall-like setting where it disappears. I have come to watch a vanishing act, to grieve the pictures which I make invisible by seeing them.

It’s not simply that there are too many pictures to see, somehow, in the context of a festival, all of those pictures cram themselves into every frame I see. I can feel the pressure of those other movies crowding in from the catalog (what’s next??), the line-ups of people impatiently waiting to get inside the theatre (isn’t this screening finished yet? There are MORE MOVIES to see!). The sackfuls of movies, the hundreds, even thousands of envelopes which can arrive at the overburdened post box of a single festival, I can feel all that hope stuffed up inside the frames of the selected few which manage to make it onto the screen. Though I am already wondering: how could this movie be shown, when my close friend who is only capable of motion picture genius, was flatly rejected once again? Yes, I am watching my friend’s movie and weighing it against the ones I manage to see, the chosen people, the chosen tribe, the anointed. Though the banished and exiled, the ones who didn’t make it, are never quite off-screen, they too are pulling at my retinas. So as you can imagine, between the too many movies which the festival is already showing (sometimes at the same time, there are multiple programs in theatres occurring at once, I have to choose between an overhead projector performance or a shorts program from Kenya. Where do I turn? What do I leave behind?), and the too many movies the festival is not showing, I manage to see almost nothing. The frame is too full, I can’t seem to isolate a picture, to obtain the necessary distance or closeness from which to conjure a picture. Instead everything blurs into the amiable chatter at the bar after the show, the brief encounters with professionals, the people I am trying to avoid, the ones whose faces I can’t remember, in short the people who I prefer (as I prefer all people) would simply convert themselves into further pictures, so I could continue to celebrate their disappearance as well.

And after them, no doubt my own.

“How many things there are in this world that I do not want. Said Socrates, strolling through a marketplace in Athens.” (David Markson)

But perhaps I am only leaning again into the warm trade winds of nostalgia, hoping to feel again the scarcity of pictures which I imagined the condition of my “youth” (and by extension, of course, the youth of pictures). The screenings you write about, the one-person shows beginning at eight pm which you organized for so many years in Paris, where motion picture monologues could hold forth for an hour or so, followed by a strangled discussion with the maker, or else a beer for the faithful. Most important of all, this screening was not instantly followed by another. There would be a break, a pause, a place between screenings. This, I have to admit now, is what I miss most of all. At once the anticipation of pictures to come, and the digestion of those already swallowed. It is exactly this space that the festival disappears, with its endless succession of programs. Its entire organization exists in relation to other organizations, similarly dedicated, so that the proliferation of motion picture events may proceed uninterrupted across the globe. I have had occasion, when one of my small mutterings has been deemed worthy of display, to stagger from one gathering to the next, one country to the next, one continent to the next, in what begins to seem a single, unending festival running pole to pole. There will be no break and no pause.

It used to be so difficult to make a film, so expensive, the labs hostile, the cameras scarce and jamming, the light elusive. Now light is no longer a prerequisite, in fact, digital cameras seem to work best without any light at all, and movies can be made for the price of a single tape. The endless production, a production without pause or reflection, is the mirror image of a condition of endless exhibition, the endless consumption of pictures. How does the consumptive ideal of the festival work to counter the politics of globalization – or is it only one more manifestation of capital’s uncanny reach? Are avant fests little more than TV for smart people? And while we’re in the asking mode I would like also to inquire about the ending of your involvement with Scratch in Paris. Can you talk about why you started it all running, and what exactly changed? Why aren’t you still up into all that?

Yann: It is true that the festival as much as blockbuster exhibitions like Documenta and the Biennals (Venice, Sao Paulo, or Whitney) face the same accumulative problems. It is as if it is not possible to face exhibitions which are not monumental. As if small scale was definitively out of sight. When I curated the Sharits exhibition I could have fallen into that trap, trying to show all the film installations, and a lot of Frozen Film Frames. It would have been better in some ways to have one or two more FFF, but mostly it would have been pertinent to include more late paintings and drawings. But the scale of the exhibition is fine. The work is strong enough, powerful to such an extent, that it is not necessary to pile works one after the other. It was important to show the diversity of mediums used by the artist and indicate some of the issues he has been challenging all his life. In order to accomplish this goal, the exhibition offers multiple accesses to the work, and conveys a variety of forms of approaches using films, paintings, projections, installations, interview, data bases and so on. Such a project is small in scale compared to a festival (though it can become part of a festival, as it will be shown in Rotterdam this year) or a museum show.

But it seems to me that we have to be aware of what we do while exhibiting films. What is at stake? Does the curator wish to show his/her knowledge of a certain field, which have become so large that it is no longer possible to encompass it all? I have to confess that I like this idea that no one can master the field of cinema any longer. It has become a vast territory that you can only know part of. Our knowledge has become fragmented, sectioned. Our knowledge reflects what we are as much as the space, territory, culture we are coming from. When you deal with a festival you are offering, as I already said, an opportunity for people to wander. One of the problems with this opportunity of wandering is that, as is often the case with films, people prefer to be guided, oriented. How or why I choose this film and not that one isn’t like being in a book store or record shop or on the net where you wander and produce a kind of research which sometimes results in interesting discoveries, while other times you could not have encountered anything worse. But in fact what was important is not so much the retribution but the quest, the research, the wandering.

Being at a festival is therefore an experience where you face your own limitations and another aspect of capitalism. The “malling” of every aspect of our life through its object accumulation has been extended to film and video. In that sense the privileged moment of film reception which you mention has perhaps been erased. Or has it? Is this what we are scared of? Does our fear of this disappearance make it more difficult to admit, see or enjoy the new modalities, the new experience of film?

As you are aware, I like classical music and this enjoyment is due in part to family history. My mother played different music instruments and owing to social, and familial pressures in the fifties she dropped the idea of becoming a concert pianist. This type of music, contemporary or not, is becoming an obsolete form of culture. It’s not that people don’t continue to listen, play and record this type of music but it has become minor. In a similar manner, film is following this same pattern. Music, like films, are promoted through special events such as festivals or three day marathons. The fact that certain habits of listening are attached to certain kinds of music, or seeing to a certain manner of films, doesn’t mean that the experience of listening and watching has disappeared, only that it has been displaced. It requires other attitudes with which we are less familiar. How often do you play video games?

Some filmmakers have succeeded in imposing their pace and don’t suffer this dilution. Thomas Köner, Jurgen Reble and others know how to give a pulse in such a manner that the work will emerge from layers of images. Others will uncover strategies that don’t have to do with this kind of mystical quest, but are filled with a political urgency. But you can miss all this within a festival because you might have been distracted, or were in search of other works. So it seems that a festival is mostly a research site instead of a place to enjoy films. It is impossible to see all those films just as it would be impossible to fuck with everyone you would want to. This impossibility makes it stimulating in some ways, as much as it evokes our limits.

But let’s go back to another issue we mentioned earlier. A few days ago I was at The Tate Modern and wandered through their collection and was quite amazed by the inclusion of experimental films within the museum collection. Rooms had been created for single films which were screened again and again. Meshes of the Afternoon played in one room for instance, while Diaries, Notes and Sketches was in another, and Len Lye in a third. Each film was given a proper space, yes they were shown in loops, but there was a blank time between each screening which isolated and differentiated viewings. People could sit and watch for however long they wanted. When it was a short film people seemed to stay for the full length of the film. With Jonas Mekas’s feature length movie it was a bit different. But one point was that the quality of the projection for the Mekas was higher than for Deren, due to a different encoding. The fact that it was possible to see these films not only at a specific time, but anytime during gallery hours, rendered the work at once more accessible and disposable. The fact that these films were included amongst other art pieces is positive in the sense that these experimental films belong as much to film as to art. Obviously I didn’t have the same experience as the one you described concerning Lemon at MOMA. This experience made me think once more that it is important to give access to these films in a contemporary manner. The traditional screening still holds, it is not inaccurate, not at all. But if you can show some of these films in a museum with high definition you give them another chance to be discovered, and you might reach people you might not have if screenings were confined in the circles of (confusion of) experimental film.

One of the issues with our type of films is that the work lives only when it’s being shown therefore we should emphasize opportunities to screen the work, in order to give it presence.

I don’t know if you experienced what Beaubourg did with their exhibition Le Mouvement Des Images, in which there was a long, central hallway which admitted a series of twelve consecutive film projections by artists like Len Lye, Paul Sharits, Matthias Mueller, Richard Serra, Lazslo Moholy Nagy, Robert Breer, Rose Lowder… I had a work there screened on the floor called Shibuya. One problem related to this presentation was that there was a corridor of projections on both sides, like a set of windows, which encouraged people to wander from one window to another as if they were shopping on a street. It was not possible to have an intimate relationship with the work, only a glimpse. But a lot of people unfamiliar with these works discovered them and it was as if a new world was in sight. So it is rather strange to have, on one hand, the promotion of the specificity of a work knowing that it will connect to the happy few who already know about it, and on the other hand, a larger accessibility which betrays the condition of projection. I don’t know which side to choose, but both attitudes are understandable.

The screenings that I used to organize were a necessity of the time. For many years the Scratch screenings (in Paris) were essential within the experimental film scene. But this scene is not frozen in time, it has to change depending on the conditions of production and reception. A screening followed by questions and answers is important but it is perhaps not suitable today. A master class, a lecture or a selection of films by a filmmaker might be as important as the screening of his/her works. What is at stake has to do with choice, with opportunities to give attention either to a work, or to a collection of works. We can’t any longer pack films one after another for the sake of discovery. We would be overtaken by work because our availabilities are not infinite. I sense here a common feeling between you and I facing the amount of work. But maybe we are not speaking from the same quest. I am not necessarily eager to see everything, maybe because I have already overdosed. I need to think differently about moving images and their relations to distribution, which relates to timetables of access as well as screenings. Festivals with their calendar schedules and their production of expectations work as thriller machines which are no longer entirely satisfactory for you and I. But at the same time don’t we sometimes need the recognition that a festival selection seems to offer, a warranty? Though we might be operating under an illusion. A festival works for its own sake, and helps promote filmmakers, but mostly our works are commodities.

I stopped curating for Scratch because, similarly to you, I felt I was lacking a certain passion. Scratch had become a habit, and it was not always a pleasure to make another program or series. There were some programs I wanted to work on without any limit and others that I felt I had to do, other issues were at stake. The fact that my involvement with Light Cone (the distributor) and Scratch (the exhibition venue) had to diminish was in part because I was doing all these things for free. And that made it difficult for others to be involved.