David Gatten Talk

May 7, 2005

presented by Hallwalls at the Market Arcade Films & Arts Center in conjunction with Beyond/In Western NY 2005

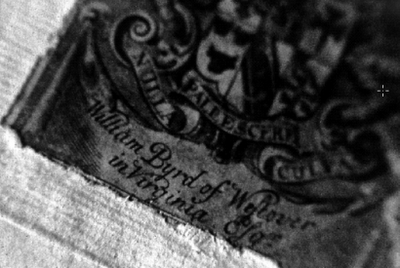

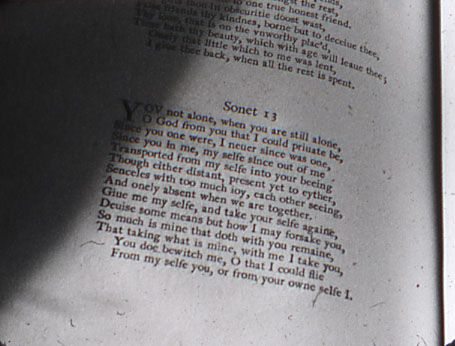

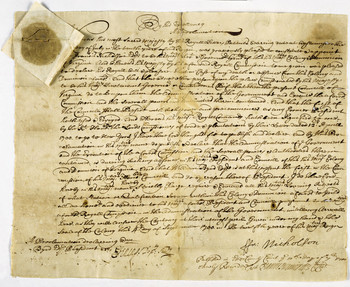

I’d like to say thank you to Joanna and to the curators from the Beyond/In WNY biennial. It’s exciting to be able to bring this work to Buffalo and so this feels like a special occasion for a couple of reasons. This is a cycle of nine films that I’ve been working on since 1996 and now the first four of those nine are done and tonight is the first time that they’ll all be shown together. I think there’s about nine more years of work and five more films. It’s significant for that reason. I know that many people here tonight have seen some of those films over the years, but for people that don’t know what all this is about: these are nine films all of which take as a point of departure a volume from the library of William Byrd of Westover who was living in Virginia during the early part of the 18th century and among other things that he is noted for, he collected the largest personal library of anyone in the colonies. He had about 4000 books. And he organized them according to his own scheme; he made sense of them in a very particular way. He died in 1744. After his son’s death in 1777 the library was auctioned off and a number of the books were bought by Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson’s books later went to the government to form the basis for what is now the Library of Congress collection. I’m interested in the Byrd collection as a site for the transfer of European intellectual, religious, scientific, philosophical thought to North America.

All of the films take a book as a point of departure. I’m interested in those books and in William Byrd, his daughter Evelyn Byrd and certain events in the life of that family. The films are also explorations in a biographical sense, in a historical sense of that time and that family. They are also all films about different manifestations of division. Division of landscape; division of objects; division of people across time and space; the categorization of knowledge; the division of labor that existed in Virginia and most of the colonies in the early 18th century and the way that can be envisioned in plantation architecture; the line between life and death, between knowing and not knowing.

The second reason I feel this is a significant place to bring this work is because I always associated Hollis Frampton with Buffalo. Frampton’s work has been deeply important to my own thinking, his films certainly but perhaps more than that, his writing. It makes me very happy to bring this work to a place where Frampton spent so much time.

Thirdly, I’m a little overwhelmed with the people who are here right now and the distances people have traveled from Boston, and New York, and Toronto, and Detroit, and Ithaca, Syracuse… all sorts of places. Some of you know I’m a little bit under the weather right now and had a turning point in Toronto a few weeks ago at the Images Festival, and it’s great to see so many people from Toronto again in such short order. I feel really blessed I have such a good community of people in Ithaca where I live, and such strong support. I have fantastic students there and that is one of the things that keeps me going as a filmmaker, that keeps me thinking, active, enthusiastic and inspired about cinema.

One of the other things that keeps me going these days is knowing that this work has, and I hope can continue to participate in, a conversation. I feel lucky to have been able to show it as often and to as many people as I have. There are a lot of people who have made that possible. There is one person in particular who has been consistently interested in, advocated for and supported this work and has shown it all over the world and so for that reason I would like to dedicate tonight’s screening to Mark McElhatten. I’m very happy that he can be here tonight.

There will be slight pauses between the films, I don’t want them to run together too much. We’re going to look at the films in a different order than how I made them; this is a series of films made out of order. The first is Secret History of the Dividing Line that’s about 20 minutes and it was made in 2002 and then we’ll go to The Great Art of Knowing and that’s a 2004 film and it’s 37 minutes long; the third one is Moxon’s Mechanical Exercises, that’s 26 minutes from 1999 and then we’ll end with a film from 2001 called The Enjoyment of Reading, and that’s about 18 minutes.

(screening)

Q: Can you describe to us what films five through nine are going to be?

DG: The fifth film is based on a book by Robert Boyle called Occasional Reflections on Certain Subjects, and that is very much Evelyn’s film. I think there’s a trajectory in these first four pieces, from the expedition led by William Byrd to the introduction of Evelyn in the second film (Moxon’s Mechanical Exercises). Although she’s never addressed, it’s Byrd’s way of thinking about her. She gets it all in number five because that’s the centre of the nine and she’s where I identify. I’m interested in William Byrd, in his library, the things he wrote, the things he did, but the emotional center belongs to Evelyn and I. Then moving back out, La Plume Volant, or The Flying Pen is the basis for number six. That book is a manual of short hand that William Byrd used to devise his own short hand code which he used to write his secret diary which was not actually deciphered and translated until 1929. That film will be about surreptitious communication, about secret languages, Evelyn and Charles’ love letters, and William Byrd’s secret diary. Then we go back to the expedition. I spent a month one summer actually trying to find the old dividing line, using secret texts, old maps and contemporary ones, trying to find the 57 locations listed in the appendix of the secret history of the dividing line and then film at each one, and that process is still incomplete. I filmed at 42 of those 57 locations. The dividing line, the border, has actually moved about 30 miles to the north since 1728. Virginia keeps getting smaller throughout history, all of the East coast used to be Virginia and it has slowly been whittled down. There will be people in that film, and sound. Color is introduced in this last one, the next film is predominantly in color, then sound gets introduced in six, people come in, in seven with sound in a big way. Eight is Half Penny’s Principles of Architecture, that was a book about how to design your plantation so that’s the image that I’m using to talk about slavery. I’m particularly interested in those spaces that were the liminal spaces: the kitchen, the stables that were used by both whites and blacks—and where those boundaries existed and where they did not, and how the actual architecture played into that. The last one is the ghost story film: The Ecstatic Heavenly Journey which is about Charles and Evelyn and their affair and its outcome.

Q: It’s such an amazing project and so well researched. But how you see it as cinematic?

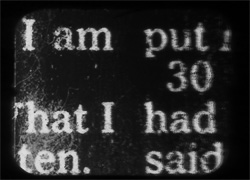

DG: Right, why is this not a book? I’m certainly interested in the graphic nature of the printed word but I’m also interested in the rhythms of speech and music. In cinema I am dealing with graphic elements which exist in time. The fact that you’re reading at a pace I determine means that you can read more or less at any given moment. I want to give and take in this process of presenting material. I’m hoping that keeps the suspense up; that you don’t always get it all and that things will accumulate. In the broadest sense, that’s why.

When I started this process I didn’t know what I was doing. I had been making what I think of as landscapes that are actually greatly magnified cement splices made with a misaligned splicer. I had been thinking a lot about Agnes Martin’s work, and I was just tearing pieces of leader and splicing them back together. Then I saw a footnote referencing the dividing line and the secret history of the dividing line and thought ahh! I’m going to steal that title. Splices are important divisions for cinema, I was thinking completely formally about defined durations. But I thought if I’m going to steal this for my title, I should at least go and look it up and see what it means. This was the summer of 1996. I went to the library thinking I was going to be there for an hour and it’s been nine years.

I first encountered texts about the expedition which mapped out the dividing line between Virginia and its neighboring states. I was in graduate school and knew that I was supposed to be making films but I was putting that off and going to the library. For two years I did this, without making anything really. I got interested in Byrd’s library then became really interested in Evelyn, and her story. She was his oldest daughter, and in 1723 she was taken to England to receive her formal education. There she met and fell in love with Charles Mordant, who was the grandson of the 3rd Earl of Peterborough. William Byrd eventually found out about this and it was a disaster because Lord Peterborough was his main political rival in England at the time, and the Peterboroughs were Catholic and the Byrds were a good New World Protestant family. So, when he found out about this he shipped her back to Virginia. And there she refused all suitors, it turns out that between 1726 when she came back and 1735 she carried on a secret transatlantic correspondence with Charles Mordant, with letters carried back and forth by people on ships, sometimes only a letter a year. I was very interested in their relationship that existed only through text and took place over time.

In 1735 Mordant traveled to the colonies under a false name, infiltrated Virginia society, contacted Evelyn and made plans to elope. They booked passage on a ship with the help of William Byrd’s secretary who it turns out was also in love with Evelyn, and ended up betraying them. Charles was tied up on the ship, while Evelyn was prevented from getting to it. The ship was lost at sea and everyone died.

Her best friend was Ann Harrison, the very young wife of the owner of a neighboring plantation, and they used to walk—there’s this wonderful description of their walk along the borders of their two plantation in this grove of trees, and the story goes that they had made a promise: that whoever died first would attempt to come back and contact the other person and try to let them know what it was like on the other side. In the spring of 1737, following Charles’ death, Evelyn wrote to Ann Harrison that she was too heart broken to go on, that she was sure that she would die but that she would keep her promise and try to come back to her friend. Two weeks later she died, though the records show no illness. The cause of death was heart failure. She was twenty nine. The following spring in 1738 marked the first of seventeen recorded sightings of the ghost of Evelyn Byrd, on or around the estate of Westover. She appeared first to her friend Ann Harrison. She’s now a fairly well known Virginia ghost, you can read about her in various books. It took me two years to piece all of this together. I didn’t know what I was doing, I didn’t know it was a film at first.

I was moving and taking things down off the wall in a small apartment in Chicago. There was lots and lots of stuff on the wall, including a photocopy of a lithograph that had been given to me by a teacher showing a woman turning away and her hands sort of dissolving. My undergrad instructor had shown this one day in class while discussing the myth of the handless maiden, and I had really loved the image and I think Joanna knew that and ended up giving me this photocopy. I put it up on the wall and said, oh, that’s Joanna’s handless maiden. But taking it down from the wall and packing it up I found written on the back the title of the piece that had been on my wall for these seven years. “Evelyn Byrd, the Ghost of Westover.” I’d been researching her for the last two years and at that point I felt that I’m a filmmaker so this would become a movie. Then I found the things I was interested in, in terms of cinema and language and reading and graphics and music. All of that followed from this contact.

Q: Susan Howe is very present in your work. Maybe you could talk a little about that.

DG: Absolutely. Like Frampton’s writing I’ve found her writing to be not only inspirational but instructive. She is someone who works with text as image and is deeply engaged in American history. She even has a book that’s called Secret History of the Diving Line, which is mostly about her father and the book he wrote about Oliver Wendell Homes, but there are seven or eight lines of Byrd in there. I was certainly thinking and reading from her about translation when I was making Moxon’s Mechanical Exercises.

Mike Zyrd: Seeing these four films together, I think that three contained references to Robinson Crusoe.

DG: Good, excellent! Yes, that’s correct, and there will be more. God, how did you see all three, that’s fantastic, it’s so quick in one of them. I will reveal no more. That’s one of the things I’ve been dropping in and you’re the first person to pick up on them. Not much is known about the ship wreck obviously except that no one came back. But I have some ideas about that, so Crusoe is going to play a part.

Q: Could you say a little about gaining access to Byrd’s collection and how that happened?

DG: It’s been surprisingly easy. The collection as such doesn’t exist anymore. The objects are dispersed but records remain which preserve the collection as an idea. In 1958 there was an article published in The Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society by a man who spent ten years of his life trying to find Byrd’s books and this article details his search. He started with the auction of 1781 that you see the announcement for in the second film, and followed the paper trails as far as he could get. Out of the 4000 volumes he had actually located, by 1958, 400 of them. And in subsequent years, before his death, he found 200 more and ascertained that at least 1200 more were destroyed in fires. A couple of years ago a book came out that reprinted the entire Stretch catalogue with all 4000 volumes in it—it’s an incredible work of scholarship, a bibliography of sorts that lists all of the known information on each of these 4000 volumes using the 1958 article as a basis. So I had a place to start, I knew where the 600 extant books were located and many of them are in Virginia at the Virginia Historical Society, many of them are in Philadelphia in various locations, particularly at the Antiquarian Society, at the Philosophical Society, surprisingly at the Pennsylvania Hospital Library in Philadelphia. At some point, 75 of the books went right there. So I just contacted these institutions and asked if I could come and film. I explained what the project was and everyone has been incredibly nice. There have been various levels of concern over the material. In some places you have to wear white gloves, and require supports and only the curators touch them and they stand right there while I set up the camera. In other places they just bring them right out; actually at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia where I was working with the oldest and most fragile stuff, they set them right on the table, I could take them anywhere in the building. A conservator came around occasionally to see what was I doing but they let me set it up. I sat and waited for six hours for the light to be right. People have been great. I think that people in libraries who are working with these old books are so excited and bewildered that someone is making a movie about them, that they become very enthusiastic and take some ownership in the project also. So much of my work is studio bound and it’s by myself and I really like people, I’m not trying to get away from people in my studio—so I love the chance to go out and actually have these interactions. In Virginia there was one particularly fragile book that they bring out only once every five years because they don’t want it exposed to light. I did the shot and gave them the book back, then realized I was shooting Tri-X but I had left the 85B filter in, so it was the wrong exposure. It was critical to The Enjoyment of Reading so I actually went back to the counter and asked, “Can I have that back one more time?” They checked it out to me again so now that book can’t be checked out for ten years.

Q: Could you tell us a little bit about why you chose to show them in the order you chose to tonight?

DG: I hope that the information unfolds and accumulates in a certain way. I’m interested in moving back and forth between the films which convey very specific information and the films which are dealing with more formal and conceptual things about reading and not being able to read. I’m hoping that you continue moving to different places even as things reoccur. I do think that this a narrative project. I would say that it is largely a non-fiction project but I believe there is a story, I’m trying to tell a story. And so I do have an idea about what order I want the story to be told in.

Reanimation is significant in these films. Taking things that are still and making them move again is important and I think that’s an idea about history in general. How do you deal with history, how do you make it present? The Great Art of Knowing is a film about trying to reach back and contact something that is dead and make it alive again. Finding that bird on the lawn was really important. I had already started working on the Leonardo Codex of birds, and was interested in birds and the Byrd family, bringing the Byrds back to life. Using the image of the bird and trying to reanimate it on film so that it’s flying again was really important. The idea of the after life; that’s why I feel the order has to be The Great Art of Knowing followed by Moxon’s Mechanical Exercises, a film that’s looking at the Bible but it’s also the Gospels. Again trying to pull something back up. And then by the time we get to Enjoyment of Reading Charles and Evelyn are alive again and we’re going to get their story. I think that’s a highly dispersed answer to your question—there’s logic for me and I’m curious to know the many logics that could be derived from the sequence of these films.

Q: As you make each film, do you find the others are giving you more ideas and making it easier to continue to make these films?

DG: I have tried not to think too far ahead, and not to map this out too specifically because I don’t want to end up executing a plan. And so far, I’ve been able to make the films in a way in which I’m able to respond to things that are in my life. I consider them, even though highly veiled, highly autobiographical films. I didn’t know why I was making Great Art of Knowing, a film about separation from someone you love, and death, because I was very happy. I have a better understanding of that film now than when I made it. While I know what the five films are that are coming next, I think that there is enough room for me to respond to whatever is going on here (points to himself) and find that in the film. That’s part of the reason the films have been made out of order: I’m not positive which I will finish next. I’m well into three of them, but we’ll see which one of them catches hold this summer. I’m trying to preserve the ability to respond; I also have made other films that are not Byrd related, and I’m into three other things now that are not Byrd related, so that allows me to not feel constrained by the overall project. I’ve also given myself a lot of time. I have until 2028 to finish the series because that will be the 300th anniversary of the dividing line expedition, so there’s time in there. I hope to be done in ten years, but there’s time.