From Lebanon to Kelowna: an interview with Jayce Salloum

For a committed politico, he sure talks a lot about beauty. His camera glides over surfaces, it caresses the light from a bus window, the way a hand falls halfway out of the shade, offering only the promise of another secret. And it’s a good thing, because this beauty permits him access to what he’s most interested in, it allows him to endure, if only for a moment, that which cannot be endured, to hear the stories of survivors.

Beauty is complexity he says, and I can only nod, trying to catch the long sentences as they float past. Most of all I am grateful he is doing this work, the situation of the Palestinians, for instance, is far too important to be left to journalists, who for the most part have given up even the attempt to provide a picture of these stateless exiles. In the wake of so many pictures dedicated to erasing, of making invisible, he reverses the field. What does it mean that we are able to turn to Jayce’s tapes from ten and twenty years ago, and learn more about the present situation in Lebanon than any up to the minute broadcast? He lays bare the mechanisms of seeing, the histories we carry with us when we try to enter the city of Beirut, or the Okanogan Valley. His seeing issues these truths like a wound that will not heal, a speaking wound which refuses to close (Delillo: “The past brings out our patriotism… we want to feel an allegiance.”) In his considered reflections on reflection, his careful walk through the minefields of metal and language and casual misunderstandings and power he holds up in front of him a beauty to make the next step. When the suffering is too much, when too many innocents have been slaughtered he uses this beauty as a shield in order to get close, he needs to get close so that it is possible to look and to see, to bear witness, to tell the story.

Mike Hoolboom: Your beautiful and harrowing tape untitled 3b: (as if) beauty never ends.., (11:22 minutes, 2000/2002 ) (is anchored by the voice of Abdel Majid Fadl Ali Hassan (in Burj el-Barajneh), a Palestinian elder that has been living in refugee camps in Lebanon since 1948. Here is an excerpt:

“So we walked, and I kept looking around in wonder and amazement, I couldn’t believe I was back on my land. God is truly great. When we got to Kweikat I bent down and kissed the soil. We headed to the cemetery and I noticed the untended grass and weeds. I also saw the barbed wire fences that the Israelis had erected to stop the Feyda’een from returning. We reached the areas where our homes used to stand, they had all been demolished with nothing left but the foundations of the houses, standing bare of the stones which had been stolen. Pine trees had been planted among the ruins. We continued walking through these former houses and yards. While looking around I felt as though I could hear something, I imagined that my house was speaking to me.. “Are you aware that it was my arms which received you the day you were born?””

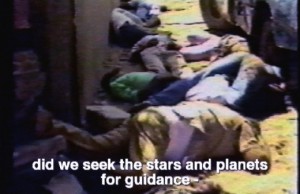

We never see the speaker, instead you show us fish moving in slow motion, shadows passing over flowers superimposed with the remains of an Israeli sanctioned massacre: corpses lie on the streets of the Palestinian refugee camp of Shatila and the contiguous Sabra neighbourhood. The exile who has come home, and the landless who will never go home again. Why do you offer us this juxtaposition? Can you talk about these massacres which are both widely known and absolutely repressed? Where did this footage come from, has it been widely distributed?

Jayce Salloum: The untitled tapes are part of an ongoing videotape without end. I originally intended for the untitled videotape to start at timecode 0:00:00 with continual additions of edited material until I died. I had hoped people would screen or order it by sections they would designate, i.e. 0:10:30 to 0:40:02. Later I realized this would make distribution practically impossible. So I divided and produced the tape in parts, most of which are available individually as single channel works, or shown together in an installation context. untitled extends and continues my series of projects addressing social and political realities and representations. It isn’t modeled on the viewing of art (i.e. painting) but on an approach to research or reading, an active living archive. The parts play off of each other creating a literal and imagistic experience of the physical/visceral and of the underlying subjectivity experienced through the body, as crisis, place/nation, and metaphor, or in transition and shift, and in the recounting or enunciatory nature of the interstitial site.

To get back to your original questions, in September 2000 I videotaped forty hours of conversations with Palestinian refugees in Lebanon at six different camps spread from North to South. It usually takes me several years to make a tape, to continue research and to consider the issues and implications, so the material was still sitting on my shelves when on April 3, 2002 the Israeli army started its attack on the West Bank Palestinian town of Jenin and its refugee camp, slaughters were carried out and covered up as usual, and any attempt for a timely investigation by the ICRC (International Red Cross) and the U.N. were refused by the Israeli government until they could literally bury the damage. I was moved to get some part of this material out because it represented one of a series of massacres that Palestinians have been subjected to and that then Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon was either directly responsible or implicated in since the Naqba (catastrophe) of 1948 and the Qibya massacre in 1953. The footage that was released of the Jenin incident was ultimately so reminiscent of the footage of the Sabra and Shatilla massacre (1982) that it made sense to collapse the space of time and to make an homage and commentary on this series of ongoing atrocities against Palestinian people. In the installation you see what we call ’48 Palestinians (Palestinians who were forced to flee their homes in 1948 speaking their stories of dispossession). You see Abdel Majid telling the story of visiting the site of his village thirty years after it was destroyed. And you see an elder woman, Nameh Suleiman, talking about being displaced once, twice, three, four times, from her home in Palestine, from South Lebanon, from the mountains, and from camps destroyed in the Lebanon war. You see and hear them talking on a video monitor while the visuals of part 3b are projected as ambient imagery along the walls behind. In the single channel piece Abdel Majid is never seen talking.

People have been documenting other cultures long before the invention of film and photography. Napoleon took a fleet of engravers (as well as engineers, historians, archaeologists, architects, mathematicians, and chemists) with him on his flagship, the Orient, when he invaded Egypt in 1798. This could be seen as the start of the ethnographic tradition. The depiction of other cultures as a part of a continuum. Leaders would bring painters, engravers and printmakers on their invasions to document their exploits for purposes of heroism and imperialism under the guise of scientific knowledge. Now they bring a coterie of embedded journalists.

As we’ve come to know the Palestinian condition, it’s been represented very one-dimensionally, as a corpse, a culture that’s destined to die or that is already dead. If you’re Palestinian you’re subject to many layers of annihilation: there’s cultural genocide and practical genocide, the aim is disappearance. The images we’ve come to recognize as Palestinian are stereotypical and thin. There’s little recognition that it’s a rich life, even if you’re living in a camp you would still have a garden, and other experiences of nature and aesthetics. Beauty continues even if you’re under curfew, elements of pleasure remain, otherwise you wouldn’t fight to go on living.

The tape (part 3b) explores two dominant motifs or guiding metaphors: flowers blooming in slow-motion, and the process of imaging the corpses from Sabra and Shatila. That 1982 massacre of Palestinians was undertaken by the Phalange militia, a right-wing Maronite Christian-based militia in Lebanon (allied with Israel). Shatila camp and Sabra neighbourhood were surrounded by the Israeli army, and Israeli Defense Minister Ariel Sharon gave the green light for the Phalange to go inside in order to do their dirty work.

The massacre footage was given to me ten years later, when I was working in Lebanon in 1992, I was there for a year and people would offer me things which I might be able to do something with. It was given to me by a stringer who shot it while working for AFP (Agence France-Presse). I did research at the Communist TV station (New TV) in W. Beirut that was there at the time, and found that journalists traveled in packs, like heat seeking missiles, to find the corpses. I found multiple versions of these shots of clumps of hair lying on the ground, hats, canes, or bodies, hundreds of them nearly identical save for a slight difference in parallax, shot standing a few degrees apart, hovering, framed so that they don’t show the other journalists who are there.

Even though the tape is a eulogy of sorts, a figure of recognition which the flowers indicate, I wanted to evacuate these forms of representation: the corpse and the flower. I wanted to make one disappear into the other, emptying out the usual representational tropes via juxtaposition and other devices thereby complicating them. The picture becomes more complex with the exoteric and inherent layering. Complexity is the basis for beauty, beauty is never really simple. If it’s meaningful it is complex.

MH: Is the footage well known?

JS: No, not in this state. The news media would have used only seconds of material. However, fictional or not, one has an image recall of the massacre, by name it was pretty well known, but once you’ve seen massacre footage… such as in Lebanon, or Iraq where one bomb explosion in a market is difficult to distinguish from another, they start to transpose themselves onto each other in the viewer’s mind. The massacre was large, between 2000 to 3,500 people died or were disappeared, many bodies were never found. The juxtapositions throughout the tape represent aspects and intersections of the story that is being told but are not ostensibly related. The Times Square LED ticker tape, for instance, makes connections with geo-political global relations underlying the events, notably the globalized war against social struggles, the dominate news media and the machine of capitalism… the military industrial complex we are all subject to. This LED display describes peace talks in an East Timorese context, which evokes the so-called Middle East peace process, which was never really about peace but a cyclical form of Palestinian capitulation.

The slow-motion blooming flowers, mostly orchids, are shot in my home studio, domesticity is woven into the making of this tape. Abdel Majid was taped in his living room with children milling about, people working in the kitchen and guys seated around the edge of the room. He’s probably told this story hundreds of times, and the guys listening have surely heard it almost as many times, nevertheless everybody is in tears by the end of the telling, whether they’re hearing it for the first time or a myriad of times. It’s part of an oral history tradition that’s survived multiple dispossessions, and it’s part of a domestic setting within the camp which is like a transposed village. This doesn’t occur so much now, but when people fled Palestine in 1948 inhabitants from the same villages gravitated toward particular camps. Within the tape I want to show how larger geo-political and social aspects of survival, conflict, and beauty are reframed in our daily lives.

MH: We never see Abdel Majid, though his voice floats over the dead bodies lying on the streets, as if he was a ghost speaking.

JS: It was a deferment, he appears in the installation, not the single channel version. I’ve accepted not having his image, though I always want to have a recognition of the subject in the tape, not having it visually doesn’t lessen his presence. Without a visual referent you’re not able to slot him into a certain type of person, Arab, Muslim. I don’t think people try to imagine what he looks like while watching, the other imagery fills the visual need, afterwards they may wonder. But it does create a space where the story can be paid more attention to by the viewer, it’s more visceral having these images and this text messing with them intellectually and somatically. I like working with a combination of visceral, formal and literal elements.

MH: The tape is punctuated with blank spaces, underlining the fact that something is missing, that everything cannot be shown here. There are partial gestures, hats without heads, shoes without feet. The hole in the wall offers another viewpoint, another aperture to see the city. This shot suggests to me that no matter how painful, there’s no use pretending that the wall is still intact. Instead you move towards the wound, the hole, and look through.

JS: The wall is on the edge of Shatila. It’s shot ten years after the massacre. What we’re looking through is a sniper’s hole, it could have been a shell hole originally. We’re looking out at the camp, which is part of the city, a specific zone. Camps are quasi-autonomous, neglected and denied spaces, to the Lebanese they are a type of no-man’s land because they have their own internal governings and structures, depending on which Palestinian party is in control. The demographics of the camps in Lebanon have diffused a little since the war, other people are also living there now, like Lebanese displaced from the South and Syrian labourers who can’t afford to be anywhere else.

The wound—a lot of this work is about how to visualize absence and loss. Imagistically, ruins are so easily fetishized. However, they can also be used more potently, representing a past which had been, and what’s going to replace them. In part 3b I use them metaphorically and literally in talking about dispossession, absence, denial and neglect of the Palestinian population seen through this void in the structure.

I use black frames a lot in the videotapes for a variety of reasons, initially to break the relentless naturalism of film. When you’re watching a narrative film it all seems to flow and there’s no reflective point, so the black breaks up that rhythm and creates another rhythm which is more related to the conceptual trajectories of the piece. There’s a structural element as well, it’s like in early structuralist film with black and white leader, but with content. At its most basic level the use of black is structural though it becomes indicative of absence. When speaking about the Palestinian people, their absence is very particular to political situations: either they’re left out of the equation, or they’re only incorporated when there’s an acceptable subject. Like in the negotiations that the West directs between Israel and the Palestinians, where the West (and Israel as part of the West) decides who is present and who is absent at the table, who is acceptable and who is not acceptable. It’s not a matter of the Palestinians choosing who they want, even going through the democratic process of having an election is still not sufficient, so they have to re-arrange their government again to make it somewhat passable to their own people and try to placate the powers that control whether they live or die. Absence is very real, it’s not just nothingness, absence becomes a political fact which determines survival. When the camera pans to the wall in Shatilla it carries references to history, absence and perception. Perception ties all the works together, it’s with perception that we produce articulations that formulate and support policies. That’s why confronting the perceptual process is so crucial, it can challenge, feed, and lead people along, creating a more informed or intricate discourse by way of perception.

MH: Your movie is very beautiful and lyric, were you concerned that people would wonder why isn’t it more transparent? Why not a more conventional documentary approach which would deliver a clearer message?

JS: My work situates itself partially in reaction to the conventional ethnographic form that we’ve come to know as documentary—and the information technologies that followed. I work to raise questions, insert propositions, and to counteract the fulfillment of knowledge. People are only ever seeing an excerpt, the work is inadequate on many levels as far as fulfilling their needs. I want them to acknowledge that the tape is partial, representative of a much larger body of information and experiences. In the stream of their life it acts as an interruption in a canon of thought, suspending presumed understandings. In these situations or conditions or examples or themes, I don’t think a total understanding is possible, or even what we’re aiming for. With the subjects/people in all my tapes, we can only imagine what this life was/is like, in fact we can’t imagine it. We can only have very partial glimpses or fragments of understanding at best. It’s more about other things, like materializing an approach to the material, developing a sense of the situation on the ground, addressing specific representational issues, articulating the various positions and relationships, and finding an empathy for the subjects. The work is designed for what I’ve called, “productive frustration.”

MH: You open This is not Beirut/There Was And There Was Not, (48 minutes, 1994) with a series of possible approaches to ‘Beirut,’ via home movies for instance, newsreels, TV clips and a large array of postcards which contrast the ancient ruins of the old city with hypermodern hotels and plazas. In a scrolling text you offer a collection of epithets: “The Paris of the Middle East… The Switzerland of the Middle East.” To enter the city, and to enter the picture of the city, in these always shifting views you suggest that one entry is not possible without the other.

JS: It’s not possible to have a singular entry, because every entry you make is prefaced by a plethora of others that have come before you. One of the reasons I chose to work on Beirut and Lebanon is that historically it’s a place that has been occupied by various military forces over centuries, sometimes several at one time, like in the 1980s when there were French, American, and Italian troops, United Nations forces, Israeli and Syrian armies, Palestinian fighters, and sixteen confessional divisions of Lebanon most of them with their own militias. There have always been powers at work, from large national and multi-national units to tiny gangs, and assorted resistance groups. You can’t enter Beirut without an accompanying history. Even if you don’t think you’re carrying this with you, as soon as you arrive, your history, or whatever you represent to them, is acknowledged by others. Whether you choose to represent that is not really up to you in initial encounters.

MH: There are other cities in the world which similarly offer histories of occupation, so why Beirut?

JS: In 1983 I purchased my first VCR to record TV footage which I photographed and used as large stills in photo-based installations. This work focused on constructions of the male psyche, how media influences our understanding of ourselves and our world, and how it influences our perception. This subsequently became the video footage for my first videotapes (1984-87). I continued to use TV footage critically in the tapes that followed. Introduction to the End of an Argument, (43 minutes, 1990) deals with how the ‘Middle East’ as an object for study, engagement, discourse, or exploitation was and is constructed in the West. The tape is still in circulation because the same representations continue to be recycled and reproduced. With that tape, the previous, Once You’ve Shot the Gun You Can’t Stop The Bullet, and the later This is not Beirut.., a lot of the questions were about issues of the psyche and the construction of representation and how those representations were used in the actions of our governments. Where have our tax dollars gone, who are we supporting, who does that affect, where are we displacing people, who is it funding?; Those questions were aligned on a practical and a conceptual level: how does representation construct meaning and how does that produce or inform identity and larger political processes. This led me to thinking about other sites where this process was enacted, geographies, histories, countries and cites.. and to Beirut. Beirut is the epitome of the historic city. The other reason I wanted to go was because my grandparents were from Lebanon, from the same little village in the Bekka Valley. I was curious to see what relationship the conceptualization and actuality of this place had to me and my own alienation. I developed several projects to carry out in Lebanon in 1992, just as the civil war was ending. Beirut was relatively peaceful then. South Lebanon remained occupied and was in people’s minds only when there were major events, like when the Israelis would break out of their “insecurity zone” and bomb a power plant near Beirut or recommence shelling Lebanese villages and highways with their canons and jets. There was a resistance movement that Hizballah had taken control of which ultimately drove the Israelis out (in May 2000).

Postcards introduce interesting past lives. You had these pre-civil war postcards, made before 1975, filled with bright, dye-transfer colours, typically idealistic promotions. They were hard to find, sometimes appearing in shops that were re-opening, in dusty corners. The Tourism Ministry, hoping to regenerate business, went back to photograph the same locations. In one shot in This is not Beirut… at the Place des Martyrs (where the Ottoman Turks hung Lebanese nationalist resisters in 1916), I hold out one of these pre-war postcards in front of the lens, then move it away to show the site in its present day state. It’s since been flattened to make room for what I’d call a mythically inspired neo-orientalist-souk-like-mall environment, whose shops are so expensive that the people who used to frequent this most public of all plazas or who lived in the neighborhood can’t afford to shop at now, but for the visitor it looks spectacularly exotic, and the setting itself has more recently been appropriated by Hizballah supporters trying to force the government to fall. It is likewise on the Green Line between East and West Beirut where opposing militias fought across this division line and set up sniper posts. There are Greek ruins and Phoenician ruins buried there along with contemporary ruins, mid-20th century it used to be a very modern square. I have a postcard of the square with a marquee advertising a Jean-Luc Godard film with Brigitte Bardot (Contempt, 1961), the Lebanese were always proud of their cosmopolitanism, they would adopt what they saw as the best part of the cultures that occupied them. It’s an interesting sort of pride built on knowledge passed on through interactions with their occupiers and places they’ve been influenced by. Its similar to the way that Islamic, Arab and Middle Eastern culture and science spread through Europe from the eleventh to fourteenth century. Commonly referred to as the Dark Ages because knowledge came from elsewhere, it wasn’t until the fifteenth century that Europeans took that knowledge and developed it for themselves, and that was named the Renaissance (rebirth).

I would take these pre-war postcards down to the square to show the kids that were hawking their wares, coffee and snacks and things, and we’d talk about these finds, and by the end of my trip the kids had started collecting postcards themselves and developed their own little cottage industry, trading them like baseball cards and selling them to recently arriving tourists and returnees. In the videotape, the postcards are a comment on the multitude of possible entries and layers of reality, juxtaposing the ideal and the actual, the aggregate mythologizing that goes into the construction of a representation of a country (internally and externally). It points to the way certain things are buried in order to reveal others which are more attractive. When they demolished this area, the Bourg, they carted away the ruins, leaving select histories visible while burying others. It all depends on what the power of the moment decides, that has happened throughout history in most cities.

In a colleague’s archive in New York I found old black and white film footage made by a tourist from Florida and his wife and a friend who come through the Mediterranean by steam ship in 1932. These home movies see them arriving in the port, and views of Beirut which no longer exist. It was important to show this paradigmatic touristic approach, seeing what they can capture in a few hours before leaving again. They ham it up with the natives, get them to pose, he shoots his wife and his wife shoots him with the friend. It’s the beginning of the modernized form of the Disneyfication of cultures which are set up as a tourist industry, for consumption. It shows us how cultures are consumed on a fundamental, primary level, visiting and capturing images that can be shown to friends and family. What they recognize as worthy subjects are their own expectations, they look for what they expect and take pictures of it. They have in mind that natives look like this, the temple looks like that, they want to have pictures of themselves in front of the mosque, and labourers carrying stuff. It’s not unlike when Europeans went to Africa and made photographs with a pygmy standing under each arm as a juxtaposition of scale and hierarchy. They are captured. Whoever has the camera has the power. These images demonstrate colonial power relations.

Later in the tape, I look at the re-appropriation of ‘Western culture’ in Lebanon. You see clips from Lebanese TV showing Charlie Brown and Lucy who asks him where he’s going and tells him to be careful. It’s followed by a music video where people can phone in tributes, such as to a girlfriend or boyfriend who are having birthdays. As the videos are played people’s names appear in a large coloured font on the screen. It’s a western music video but it’s been mixed back and redesigned into a local interaction unique to that moment in Beirut—pop culture becoming part of the cultural fabric. In other short TV clips, characters express alienation as they come upon foreign cultures, in the dialogues of Captain Kirk and Spock from Star Trek, or the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles’ introspective quips. In these partially humorous bits and throughout the tape, I’m positioning myself as a part-time orientalist , visitor, sometimes tour guide, artist, native and/or other.

The entry into the city is replayed in another sequence where a chronology of headlines appears as a series of scrolling texts, each of which characterizes Beirut/Lebanon in six words or less. In the pre-war period the list includes ‘PARIS OF THE ORIENT’, ‘CITY OF BLISS’, ‘Crossroads of Civilization,’ etc. During the civil-war titles announce, ‘City of Regrets,’ ‘Bastard French,’ ‘A Byword of Barbarity’ and ‘LEBANAM’ comparing it to Vietnam. In the post-war period they shift to, ‘Une Ville Qui Refuse de Mourir,’ ‘MILLE FOIS MORTE, MILLE FOIS REVECUE,’ etc. This sequence allows us to look at these singular descriptions which have been applied from Vietnam to Lebanon, from Lebanon to Yugoslavia, from Former Yugoslavia to Iraq and Afghanistan, whenever so called ‘Balkanization’ or conflict occurs. Our systems of understanding are so limited we transplant metaphors from one zone of conflict, super-imposing them onto another.

MH: Is that because media shorthand demands complicated situations are reduced to headlines or is it part of a status quo politics in which mainstream press colludes with the reigning empire (by continuing to report whatever national leaders say as ‘news’ for instance)?

JS: It’s both, they feed off each other. Whatever the media dishes out is due to our acceptance of what is being produced, it regurgitates itself, and we short change ourselves. The foundation is our education system, that’s where passivity and conformity is ingrained, that’s where we learn to accept what we’re told uncritically. We are trained to accept that we’re not going to be able to know about a lot of things, that we’ll have to rely on experts. We’re taught to specialize, not to develop fluid patterns of recognition or accept encounters that aren’t instantly understandable. We are not taught what to do with experiences which require contemplation, investigation and reflection, that are not pre-packaged?

MH: You’re suggesting that we concede large areas of our lives to experts: the plumber fixes the bathroom, the news anchor fixes our view of the Middle East.

JS: Or to patterns that have been provided for us, or that we’ve accepted and have become normalized within our way of living. They are so systematized and naturalized we don’t recognize them as ideologies any more. Part of our ideological apparatus says that we’re not equipped to analyze complex political situations, we’re looking for someone else to do that work and then we’ll adopt it as our own. We’re a very controlled and well behaved society. We’re afraid to ask questions that might disturb people, that’s what happens in a repressive state.

MH: There’s a wonderful moment when co-conspirator and fellow artist Walid Ra’ad is speaking to you in a parked car about the traditional problems of ethnography. The camera pans away as he’s speaking, taking in the neighborhood, before returning to him. This shot suggests: foreground or background, where should the focus be?

JS: How do you map a people or a territory? A distinction between background and foreground is antithetical, they are inextricably fused. One of the threads in this tape is the inadequacy of representation. There are scenes of note taking, scribbling, sketching, demarcating and accounting, there are multiple references to the way diverse forms of representation have historical precedents for imperialistic purposes. How do you map in a way that is not about possession or ownership or occupation, how do you map to create contiguous, overlapping, and integrated zones of contact, and map in an intelligent way that can critique and complicate the process while you’re doing it? Ethnographies are another form of mapping, the camera is used scopophillically, an exacting and extracting way to interface with culture and society. The discussion continues with Walid when the camera pans away. He’s not central to the frame anymore, this theoretically introduces the rationale behind a supposedly benign pan. We’re talking about producing local knowledges and whether anyone is well placed to make those representations. Is it the anthropologist’s ‘native informant,’ an outsider or some combination? Cinematically, the pan is used to capture landscape, to locate and position, in addition it’s used militaristically to map out territories which will be invaded and destroyed. My camera movement recognizes the problematization of the pan and at the same time shows the neighborhood and tries to make evident our positions there.

Walid plays the role of my alter-ego. We have conversations throughout. I’m not setting up a polemic between the two of us, he’s re/presenting matters I’m questioning and vice versa. I invited him to come to Lebanon with me to work as my assistant for the year, because we were working so closely, half way through I asked him to co-direct Talaeen a Junuub/Up to the South, (60 minutes, 1993) which was the start of his work in video.

MH: Here’s another quote from someone you speak to. “I’ve noticed in your field that there is something called representation. In Arabic there isn’t such a word.” What does this mean?

JS: It’s a combination of things. I often went off on my own, rambling about taping, and photographing. Walid left me for the last few months and lent me a car of his family’s. By then I had learned to maneuver on Beirut roads where everybody drove in every direction no matter what lane you were in. There were no observed stop signs or working traffic lights, it’s was all hand gestures and car horns. You had to drive fast and aggressive, an interesting chaos indicative of the situation within the country.

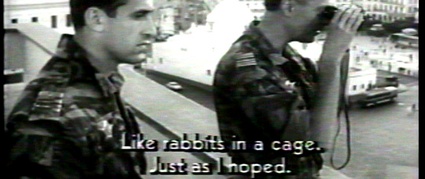

The shot you’re referring to was next to the Place des Martyrs, in a building on the Green Line that was occupied by the Syrian army. Locals believed these bombed out buildings were strewn with land mines but I would go into them as long as there were footsteps in the dust in front of me. I’m walking up the stairs of a building that’s partly in ruins, joined by a couple of Syrian soldiers I met outside, they’re pretty casual though still in uniforms with AK-47s (submachine guns). There weren’t many people who would walk around this area, let alone with the Syrian soldiers. Some would see them as allies while others regarded them as occupiers, depending on what constituency you identified with. As a foreigner my position was much more difficult to pin down. In this case, I assumed the role of a tourist with cameras, Lebanese heritage, and of Syrian origin , so they were happy to show me around and relieve their boredom. So, we’re walking up these fractured stone stairs together, it’s a dark reverberating chamber, light pierces through bullet holes and where windows once stood, the image shaky and askew—shot from waist level. There’s a metaphorical dimension as we climb towards the top, trying to reach an unknown summit of understanding, a climax in this rambling conversation that I’m having in my broken Arabic. I’m talking and taping and climbing the stairs at the same time, there’s key words that come up in the conversation… we exchange names, they tell me where they’re from, one is from near Jordan, oh yeah do you know so and so I ask? I tell them my name and he tells me that he’s named “Jihad,” I pause wonderingly and mumble, “Oh, Jihad!” There’s funny little slips of moments inside the circular stairwell, climbing, there’s understandings and misunderstandings, connections and disconnects all the way through that have meaning and add to the layering.

To highlight the difficulties of articulating the project of representation, I superimposed the audio from a conversation Walid and I had with a few guests in someone’s living room where we talked about what we were trying to do in Lebanon with our projects. I say it’s questioning and producing representations, a professor and journalist friend of Walid’s asks, “A representation of what?” to which I respond, “A representation of representations.” They laugh uproariously. Walid exclaims in Arabic, “No, no, he’s right, that’s what we are doing!” Then the friend says that in Arabic there is no expression for the way we’re using the word ‘representation.’ He goes on to say that he’s going to invent this word. That’s when we arrive at the building’s summit, this Babelian tower. You expect a sign that you’re arrived somewhere significant. There’s the bright blue sky and the brilliant rays of the sun pointing through the rubble of shattered walls on the top of this fragmented spiral tower, but that’s about it. Representation, alienation, connecting, disconnecting, and assumptions carried with us – this tape tries to produce something analogous to what we were trying to do and the complexity of our positions.

MH: You went to Beirut with a project to lend cameras to people you would meet along the way. You discuss this in a long chat with Walid while driving around Beirut, trying to decide whether this project is still worthwhile.

JS: At various times in this tape we’re talking about the projects, the proposal, the tapes—there were two single channel tapes made there which I see as complementary: ..Up to the South and This is Not Beirut.. What I did with one tape I couldn’t have done with the other. ..Up to the South speaks more straightforwardly about specific geo-political questions, and has subjects directly addressing the viewer at the other end of the camera. This is Not Beirut… is more self-reflective and self-reflexive in style—although both tapes are equally conceptually based.

The premise that I received funding for to go to Beirut was to take five Hi-8 video cameras, an editing suite, and tripods etc to develop projects with whoever wanted to make tapes, at this point in their lives after the ‘civil war.’ From these tapes I would put together a program that could be brought back and shown and distributed. Discussions as featured in This is not Beirut.. questioned the point of doing this, once again we would be creating images of Lebanon for consumption in the West. Would this simplify the situation for viewers and why would we want to do that, especially because we’re critiquing what this involves anyway. Do Lebanese know more about this situation than we do, just because they’re here (in Lebanon)? Who has the position of knowledge that you want to privilege, and why do you want to privilege that knowledge over another? We knew that whatever was released would be taken as fact, as the reality.

MH: Especially if the work is produced by folks living there.

JS: Yes, it would be more “authentic.” A discourse of authenticity is reoccurring these days, the more Lebanese you are the more purity points you receive. Programmers are returning to simplistic notions of identity as a criteria of quality: was s/he born there or just passing through? Instead of asking what are the levels of engagement within the work.

The project could never be exactly defined. I wanted there to be ambiguities, people were wondering what exactly it was, and Walid was challenging me, and together we were challenging the project, whether it should still go on. In totality this ‘Lebanon’ project was very multi-faceted: the production of sixteen videotapes produced by individuals through the workshops in my studio, the two single channel videotapes, my large photography and text project (sites + demarcations), and collecting objects and footage and using them in a preliminary layout for the intensely dense and complex installation, Kan ya ma kan (1988-1998) with five videotape loops and half a ton of material/documents/reproductions/files. We held video workshops regularly, on weekends people would come and drink scotch and we’d show tapes of video artists. People became friends and hung out. It’s a very hanging-out type of culture. Wherever we’re trying to work there’s layers of politics that we can choose to embrace or not, it doesn’t matter what area we’re working in. I think that’s what determines a work’s level of engagement, is how it chooses to interact with the possible access points, the multiple layers that people can enter into the work, and what it does with those layers of expression, information and articulation.

Numerous shots in the two tapes were made through car windows as we travel in a vehicle that represents both a physical and metaphorical separation from the landscape and socio-political sites we pass through. Walid’s distance is slightly more ambiguous because he grew up in Lebanon, but a lot of his recent life and formulation of his process occurred in the United States. This type of gaze, this view(ing)—out the car window—recognizes and marks distance, shot through the reflecting, dusty, glass; visually impaired… So much of the tape is shot through layers, reflecting upon the mediation involved, the strata of perceptual filters between understanding and encountering of any sort.

MH: The camera often provides a passing glance or partial look. You set the camera down on a table in a bar, and while people are speaking we see only a pair of hands, or a sleeve. You refuse the whole picture, always insisting on the fragment.

JS: Is there such a thing as a “whole picture”? I don’t think so. Every frame, every image is a fragment of some larger whole and every whole a fraction of something else. Each fragment, each frame acts synecdochically, as signifier and reference, literally and metaphorically.

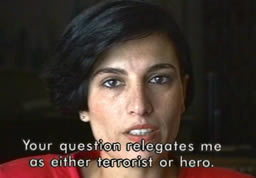

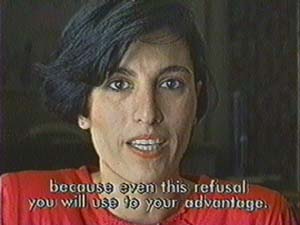

MH: ..Up to the South begins provocatively with a woman saying, “If I simply wanted to refuse I would not be doing this interview. But if I don’t do this interview I cannot express this refusal. You put me in an uncomfortable position because even this refusal you will use to your own advantage.” Damned if you do or don’t: is this the position of the post-colonial subject, the one who does not sit behind the camera, but in front of it? Why did she feel that there was no way for her to say what needed to be said?

JS: The paradox is that if you resist speaking or refuse to speak in fear of being co-opted there is no way of anyone hearing or recognizing your refusal. Your resistance may go unnoticed. The point is that anything you say can, and perhaps will be used against you by the media, academia, and other information/knowledge industries outside of your control. We wrote this opening sequence as well as the ending sequence with Zahra Bedran, the women performing these parts. The ending sequence refuses to accept Lebanon as a laboratory for others to exploit.

MH: A Lebanese resistance fighter, imprisoned for four years, tells us that the compound where he was incarcerated (El Khiam detention centre) used to belong to the French, then passed into the hands of the Lebanese army, the Palestinian resistance, the Lebanese National Resistance Movement, and then the Israelis . “It’s strange how this centre’s history reflects the history of my country. This country upon whose sovereignty so many have infringed.”

JS: The significance of the centre in this clip is how it represents the flow of histories. You don’t really need to have a visual depiction of the centre, its physicality is important, yet conceptually it’s secondary. Subsequent to the making of ..Up to the South, the centre was liberated along with South Lebanon in 2000. It was then controlled by yet another party on this stage, Hizballah.

MH: A woman from Kfar Roumane describes an Israeli shelling she was certain she wouldn’t survive, then she emerges from the bomb shelter to find everything in her town burned and destroyed. You cut away from her and show us another lingering pan of the valley as she recounts, “If you transport the land, and the soil, people would have packed it up and left a long time ago.”

JS: This is a common sentiment. The attachment to a land where all of your known ancestors have called home. Where generations have literally built their lives. There is a word you hear expressed in the south, and in Palestine, ‘Sumud,’ which translates roughly to ‘staying put,’ steadfastness as a form of resistance, staying and working your land come hell or high water, ‘cause if you leave it, it will surely be occupied and stolen by the Israelis.

MH: In the second half of the tape you enter the occupied south and show us the town of Khiam and some of the impossibly brave who have survived its brutal detention centre. They speak of their systemic torture by the Israelis (and the SLA-South Lebanese Army, a proxy militia set up and controlled by the Israeli forces to give a Lebanese façade to the occupation of South Lebanon), all of the detainees being held without trial or representation, men and women from the ages of twelve to seventy, all tortured. It is a shocking and saddening medley of testimonies. You maintain the quick pace of the tape even here though, each is granted their moment, they come alive as individual subjects but you don’t linger, their stances are cross-pollinated, gathered and collected together. By way of contrast, in the very next scene, you offer a luxury of time to a French-speaking citizen philosopher who says that “But to defend myself, I have to become someone else, and thus I risk losing myself anyway.” Could you talk about this juxtaposition, the way you found the detainees and how you approached taping them, and what he means when he says “and this is the profound mentality of those who resist, they resist within their image, from their identity.”

JS: Roger Assaf (the French speaker you mentioned), is able to articulate and theorize many of the experiences we present in the tape, this is placed close to and surrounding the accounts from the resistance fighters and ex-detainees. We wanted to have multiple levels and conceptions of resistance represented and spoken, just as we wanted to have disparate ways of theorizing and articulating experience presented and juxtaposed. As many of the subjects are multilingual they were free to choose which ever language they preferred for each taping or section of speech. Each subject has their own enunciatory manner or methodology. There is no ‘one-way’ of describing a condition, the various positions people are coming from, and the ways in which they speak or perform are additive, producing a richer, fuller encounter with their experiences. Each voice we present is important and recognized and adds to the complexity and layers of issues being dealt with.

We met ex-detainees through contacts we were working closely with and through detainee organizations and their supporters. Most were more than agreeable to tell their stories on tape, to start building a recorded oral history around these events. At that time there was practically nothing being shown outside of Lebanon about Khiam and the detainees, this was one small project they could participate in.

As for the last part of your question, Assaf attests that, at that moment and the contiguous history before that moment, those who resisted did not become other than who they were to resist. They resisted from within themselves and their own philosophical and other beliefs. He’s saying that the danger in resisting or invading is that you may lose yourself and become someone or something else in the process.

MH: You continue these deliberations on the representation of resistance with a long interview deconstruction, in a tape made years later. Can you talk about how that happened?

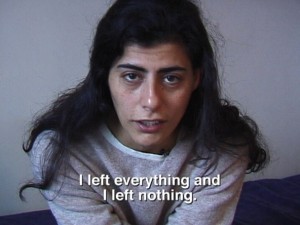

JS: untitled part 1: everything and nothing (40:40 minutes, 1999/2002) is a videotape of a conversation I had with Soha Bechara, ex-Lebanese National Resistance fighter, in her Paris dorm room. It was recorded during the last year of the Israeli occupation, one year after her release from captivity in the El-Khiam torture and interrogation center (South Lebanon) where she had been detained for ten years—six in isolation. She was captured in 1988 for trying to assassinate the general of the SLA, Antoine Lahad. Revising notions of resistance, survival, and will, the overexposed image of her, as the survivor speaks quietly and directly to the camera—not speaking of the torture, but of separation and loss; of what is left behind and what remains.

When I was in Lebanon in 1992 Soha was still in detention and I would see posters of her around the country. When we went to visit people in the occupied south, people would have her picture next to their sons and daughters who were martyred in the war. She was one of five or six women that were legendary, part of the mythology of the resistance. Their images and story-lines were used by the resistance movements for propaganda and patriotic purposes, but unlike the others who had died, Soha was recognized as a living martyr.

MH: Did she have any idea this was going on?

JS: I’m sure she knew that her image or persona was part of a gesture of recognition that included other women. The secular resistance LNRM (Lebanese National Resistance Movement) and the PPS (Partie Populaire Syrian) made several dynamic and fervent films featuring women martyrs. Some were confessional films and others pseudo-documentaries of incursions and commemorations of operations carried out. A few had more narrative elements bracketing them, including a sequence of Brides of the South , with women dressed in wedding gowns, standing on beautiful hilltops in S. Lebanon, facing the countryside proclaiming their allegiance.

When we made ..Up to the South we went to the occupied area and worked with people who knew Soha, the tape shows the El-Khiam detention centre and talks about the conditions there. It was one of the few videotapes, and the only art video at the time, that talked about the occupation of South Lebanon. It was a non-story in the West. Why? There was no value in America reporting that Israel had an occupying army operating torture and interrogation centres, that villagers could only stay on their land if a member of their family collaborated with them otherwise they were expelled or detained. The stories we usually hear are the ones the media and ruling powers want us to hear, hopefully there are other forums of information. People have a limited capacity for reflection, if you think of all the atrocities happening now it can render you incapable of doing anything.

In 1995 Mireille Kassar (a Lebanese artist living in Paris) organized a clandestine screening of ..Up to the South, at the luxurious theatre of the Institute de Monde Arab (Paris). They wouldn’t sanction an official screening, so we used word of mouth to spread the news of the event. There was a huge turn out and a long discussion followed the film. Even though I don’t see the tape as a documentary, there is a level of information that people grasped intently. After the screening Mireille and I became friends, and unbeknownst to me she later formed a committee which worked for the release of Soha and the other detainees in El-Khiam.

Four years later I’m in Brussels for a show, having just shot untitled part 2: beauty and the east, in the former Yugoslavia after the NATO bombings. Mireille called to say that Soha was living in Paris because shortly after her release the French government offered her a bursary to study at the Sorbonne. There was a gallery exhibition of artworks which had been smuggled out of the detention centre, like necklaces made with olive pits, embroideries with threads they would pull out of their shirts and weave, and charcoal drawings and writings on toilet paper given to the Red Cross and smuggled out. Mireille suggested that I come to Paris and screen ..Up to the South at the gallery where Soha and Rabab Awada (an ex-detainee in the tape) could speak after the screening. I went and Rabab and Soha talked about the continuing occupation of Lebanon and the detention centre which was still operating full force. It was a good screening and impassioned discussion. Soha and I then took off to talk over a Lebanese dinner.

We had a nice long chat in my bad French and her little bit of English, and I was pondering during dinner: should I ask her or shouldn’t I? Should I tape her or not? I asked her, look, now you’re being filmed to death, you’re telling your story over and over again to the news media, I really understand that you may not want to be taped any more, and I don’t want to be part of the feeding frenzy. We discussed this a bit, she didn’t think anything of it, and said come on over tomorrow, I’ll make you breakfast (a Lebanese dish, Kishk), and we’ll do the taping before. In the tape she states that part of her mission is the talking about it (the detention and occupation) so others can know, this as a form of resistance.

She lived in the suburbs in a small dormitory just a little larger than her old cell. I brought her roses but you don’t see me give her the them because it’s not the kind of encounter where you walk in with cameras blazing. She puts the roses on the desk near the door on a three foot high pile of dead flowers. I asked her if she would put them in water, she said no, I don’t put flowers in water, and then tells me the story of why. During the taping I get her to tell me the story again. We go further into her room (there is only one room), and I set up the camera and start taping to see what’ll happen. I didn’t have any concept of how I would use the material. I knew I didn’t want to ask her the same questions she had been asked a thousand times: what were the interrogations like? How did they torture you? Where did they torture you? For how long did they torture you? These are the desires of the press, the most spectacular details. They don’t ask questions about what it meant for her to resist. Press stories are short, highlighting the most explicit situational pornography. The press is the pornography of politics, in the same way that storm recordings on the weather channel are called storm-porn by people who make them. They’re dealing with quick sensational bytes which keep the audience from changing the channel. That’s a pretty cynical view, there are exceptions.. leave it to say I wasn’t interested in asking what she’d been asked previously.

During the taping I didn’t understand what she was saying, she was answering me in Arabic and I was asking questions in French. My Arabic has about a thirty word vocabulary at best: left, right, straight, go, stop, how much is it, what does it cost, etc. Whenever I tape somebody I ask them to speak in the language they’re most comfortable with. Sometimes people choose their original language, sometimes for tactical reasons they’ll choose another language because that’s what they want to ‘perform’ in. These are all performative collaborations, the more they speak, the more professional they become at it, in terms of the role they have. As soon as I turned on the camera I could tell that Soha had this image of a resistance fighter that she was speaking from, she had a role to play that she handled very well, and that she was used to doing. I wanted to ask questions which would recognize both her story and her representation, and in addition would make this representation malleable. I wanted to create this permeable representation that she would enter and leave, that viewers could enter and come back out of, an elastic image that would provide moments for her to open and close, so that we’re encountering more than just a role she takes on. So I asked questions about how she lived in the detention centre and now in Paris, and before in Beirut, and about the triangulation, what the distance means between the three sites.

Whenever I’m taping conversations I’ll try to set it up so the viewer can be brought into the encounter, so that they’re intimately engaged. I place the camera right here, between us, as a subject you have to look through the camera lens to see me. Occasionally people try to look around it, then after a while they settle down and talk through the lens to the potential viewer..

MH: Isn’t this the promise of every picture, that it can be seen later, cherished and recoded? You tell her that the interview will be translated, that you don’t understand now, but you’ll understand later. Does this deferral also relate to the resistance itself?

JS: Is every picture worth saving and viewing? There are no promises with videotaping. Who knows if you can ever make anything valuable out of what you shoot, gather or collect. I never know how or if something will be used till much further in time, and even if the clip will make it this far, after time passes in life, after repeated viewings during logging and editing..

Perhaps the goals of the resistance are ones of deferral, but real. You wouldn’t take up arms or resist if you didn’t feel the outcome would affect positive change. All in all, resistance isn’t that complicated, you have an occupier and an occupied people, and a resistance that grows out of this. Of course there are factions that develop, the LNRM was made out of all sorts of secular groups. With the later invasion of Israel in the early 1980s, the Islamic militias started to get stronger. Because the Israelis occupied primarily Shiite villages in the south, Hizballah grew with the support of Iran and Syria. Hizballah decimated the other resistance movements by 1985 and eventually any resistance by the smallest pod or cell came under the umbrella of Hizballah, which was a powerful position for them to be in.

I was familiar with this history, my point wasn’t to talk about how the resistance was formed, but ideas of resistance, and what it means for us, how can we be resistant, what different forms can resistance take? After her release, Soha continued to see herself as part of the resistance, she was going into international law at the Sorbonne, and talking about the conditions of the detention centre and in Lebanon. I see the tape as part of a resistance, a very mild form, it’s just a videotape it’s not a Molotov cocktail. Though I’d want my work to have fiery effects. My work resists status quo conventions and understandings by embracing multiple ways of approaching and engaging systems of ‘knowledge.’

Even though I shot this in 1999, I knew that it might be a few years before I got it out, my work takes time to produce, sometimes it feels like forever. So when I said I’ll understand later it meant that I’ll have the distance to have a broader appreciation of what she’s saying. As opposed to the news industry which has a demonstrated antipathy towards time. Instead of valuing only immediacy i.e. after five minutes it’s worthless, the distance that time provides would make the experience clearer for me and provide a better position to approach the material. Time provided a necessary distance.

MH: It’s reminiscent of a comment by Godard who recommends that television only be seen ten years after broadcast, then it becomes clear what is happening. In one of the many touching exchanges in the tape you ask her what she would title this encounter.

JS: Soha says she doesn’t like titles, she says “..normally you are the one who decides.. if it was up to me, I would name your film, ‘untitled.’” I’ve used this for the video project’s overall title and as a way to thwart the packaging or commodification of the videotape as an object. With each part I don’t normally use beginning or end credits as the videotape parts are actually pieces of one long continuous tape. This part is subtitled “everything and nothing” taken initially from earlier in the tape where she says, in reference to leaving Khiam, “In my opinion I left everything and I left nothing at the same time.” Meaning, they had nothing in the camps, no material possessions, nothing resembling a ‘normal’ life, she left that, but she left all of the other detainees that she had become so close to, that had become the world for her, so when she was released, she was leaving everything as well.

MH: She says she’s closer now to her fellow detainees left at Khiam than she was when she was detained there. “If one loves, distance is not a factor. It is the decision itself which is determinant. You decide for yourself whether you want to assert distance or abolish it, be close or far, or become dedicated or not.”

JS: It’s a question of discipline and will to determine how close you’re willing to get. You hear about a massacre and decide whether you’re going to let that impact you. Today there is war going on in Palestine, Iraq, Afghanistan, Sudan and other places of lower intensity conflict or that we hear of less frequently—we have to decide how to go on living, how involved do we get or can we get?

In these types of interrogation and torture centres like Khiam you choose if you’re going to try to survive and she decided that she was going to use every minute to become stronger and more reflective and develop whatever she could within herself. She was going to make the utmost of her time there, no matter how arduous, whether she lived or not. She was very disciplined, she exercised every day—literally climbing the walls in her isolation cell which were so close together she could put her feet onto opposing walls and climb up and down for exercise. When she was in a cell with other women they would share their stories, recite poems, sing songs, create narratives out of any remembrance. I think she refined her sense of purpose and was able to develop a form of acute reciprocal articulation that took a lot of practice and determination, and the necessity of love became all the more apparent.

MH: “We represent the resistance, the detention, the occupation, and a generation that lived the civil war…” She talks about being bound hand and foot in an isolation cell measuring 90 cm by 90 cm by 90 cm. There is no blanket or mattress, but, impossibly, a rose. She feels the rose doesn’t need to be put into water to be “recuperated.” She steals a slice of cardboard in order to frame the rose and offer it as a present to a Palestinian girl, but the guards catch sight of it and burn it. “We were not allowed to make or keep any objects that expressed ourselves, our states of being or ideology in any form.” Can you tell the story of the rose?

JS: Ah, the rose, well you’ve summarized it quite well already. The rose was slipped through an air space in the door by a Palestinian detainee, Kifah. Soha contemplates the rose and thinks, why should it be put in water, it is beautiful in itself, trying to revive its original meanings is futile, they were lost when it was cut, one could embellish the cut rose in many ways but that would be altering its natural state. In spite of it all, the “rose remained a rose, it kept its beauty, and radiance, even after it was burned.” That’s when she decided that when someone brings her flowers she won’t put them in water.

MH: I’d like to switch gears for a moment, and return to an earlier moment in your body of work which also turns around an interview with a woman, Episode 1: So. Cal (33 minutes, 1988). Here the speaker is Aida Mancillas, a Chicana woman who falls in love for the first time with a rich teenager. Her nonstop voice-over describes a fairytale story with a cruel twist of class and race. “I was fascinated by him but I didn’t like him at all.” Her dreamy tale of youth and beauty is punctured by unexpected observations, like the fact that every time she sees him she becomes physically ill. Because you let the interview run for so long, the viewer can feel the way the flow of her speaking works to cover over these breaks.

JS: I made that tape in San Diego when I was going to grad school, and this was Episode 1 —predating the start of the untitled series by eleven years. I thought I would continue to make episode two, three, four… but that same year (1988) I went to the Middle East for the first time and started working on other projects there. As I mentioned all the tapes before this deployed re-edited television footage, this was the tape where I made a bridge between someone’s recounting of their experience, their articulation of their history and subjectivity, and pre-packaged forms of histories and subjectivities as consumable objects—television objects meant to produce our psychic condition as humans and consumers. This was the first time I broached that division, I let Aida speak until she was finished and that became the length of the tape. You never see her, the same way Abdel Majid is never seen in ..(as if) beauty never ends.

Her voice is paired with southern California regional landscapes, from the car, from sites traveled to, and from television sets in motel rooms, to get a sensation of the land and cultures where the story is located, to situate her speaking. Even though the body is not visible it’s felt, but the drive produces an out of body experience. When you come from an immigrant culture you learn how to render your body and subjectivity invisible. A form of internal ethnocide takes place (and external when forced by the dominant culture). Linguicide occurs when there is no public space to embrace your language. The repression she describes as a Chicana, a Mexican-American woman, is a fundamental story for southern California. At the time of the taping there was a resurgence in cultural recognition of the Hispanic communities. There was the formation of the Border Art Workshop (Taller de Arte Fronterizo) for example, one of a few collectives and art projects developed in order to do cross-border work between Tijuana (Mexico) and San Diego. You can take a street car from San Diego and get off and walk ten minutes and then you’re in Tijuana. They’re each distinctive cities but there’s a lot of criss-crossing, which has become even more formidable now because of the increased official and vigilante American border patrols.

When she tells these stories she relates her body’s reaction to social circumstances which are tied into racial/ethnic/class divisions which she internalizes. Her illness becomes another form of representation of the experience she’s encountering.

MH: In the tape’s second chapter she describes the reaction shot, a summer affair with a working class guy, a scooter riding mechanic in Spain. She describes it as the happiest time of her life and he becomes the image of the person she should be with.

JS: It’s only the person she feels she should be with, at that moment. It probably helps that she’s in Spain and that someone speaks her language, that the context she’s surrounded by is so contradistinctive, new, and yet somehow familiar.

MH: The third act takes a different turn, the serial love story veers off into someone else’s life. She talks about her friend Carol whose father is a napalm dealer and a “monster.” The two friends drift apart, Aida gets married, and news of Carol’s shotgun suicide is initially kept from her. When she finds out, she is devastated and lapses into depression.

JS: I didn’t predetermine any of this sequencing, it was based on the encounter. This was Aida unpacking her stories. It was important to introduce the arms manufacturer, because it brings more levels of understanding to the landscape of southern California. It allows us to talk about the military-industrial culture within the very grounded, local story of her life. It’s the same thing I’m trying to do with the shots of the media, the landscape, the passing buildings, the palm trees, to offer more reflection on a site which isn’t far from Nevada and other places of military-industrial manufacturing and bomb testing. I made a second audio tape with Moyra Davey, a friend of mine, which was to have been the basis for Episode 2 –another portrait of sorts, of an unrelated life– but that was never finished as I soon left for the Middle East where I shot footage for what was to become Once You’ve Shot the Gun.. and Introduction to the end of an argument. These two tapes, Episode 1.. and Once You’ve Shot the Gun.. could be seen as bridging pieces between the earlier found footage/media deconstructions and the work where I’m focusing on specific subjects in, and locations of, conflict, post-conflict, or interstitial zones.

MH: Over the FBI copyright warning you scrawled “Copy this tape.” Why?

JS: I was going to do this with all my tapes, refuse proprietorship and make them available for mass distribution and duplication. The idea of copyright was always problematic, I disagree wholeheartedly with the commodification of video, making it into an object. Though my tapes are packaged and sold and rented, I don’t like fetishizing them as objects. That’s one reason why untitled is an open-ended project, it’s more reflective of a life and the lives of people I encounter where experiences flow and grow into other experiences, it’s more life-like.

MH: How would you feel if chunks of your tapes showed up in someone else’s work?

JS: It depends on how it was done and with what footage. If it was of people speaking that had worked with me, and it was done without acknowledging where it came from, without contextualizing it as part of another story, that would be troubling. When I’m taping people I feel there’s a responsibility to their subjectivity and stories, and this must be viewable, it must be evident. As I’m taping they understand I’m going to let their story be heard, I feel a responsibility to do that within the context that they are speaking.

MH: Once You’ve Shot the Gun (8 minutes, 1988) is framed by two extraordinary audio texts. At one point a man says in voice-over that he visits a family where the man begs him not to rape his wife, and to kill him instead.

JS: This is an ex-Israeli soldier telling the story of breaking down the door in an assault on a Palestinian family’s house. The man he assails is afraid his wife will be raped, and to avoid this he offers himself to be killed. I videotaped the soldier when I was traveling in Palestine/Israel in 1988 (the same trip where I continued to Lebanon for the first time). I shot thirty to forty hours of footage from several refugee camps, villages, cities and points in-between and tagged along with an NBC news crew from Houston, Texas who was there on a week-long ‘eyewitness’ tour. We visited representatives of different movements, including Peace Now which the ex-soldier was part of. After the news crew left, I remained in Palestine and stayed in Jabalia refugee camp on my own for two weeks with a family I’d met through a friend. Later in the videotape my girlfriend at the time, tells the story of a dream where the lower part of her face disappears.

MH: She can’t speak and doesn’t understand why. She decides to undergo an operation where the doctors peel away all the flesh from her face and realize she has no jaw.

JS: Much of this tape is about living with anxiety, alienation and denial, or the inability and construction of it and the allowances made.. I combined footage I shot with fleeting images from TV in order to look at alienation when encountering other cultures and individual people. It was shot in travels through sixteen cities or towns like Jerusalem, Beirut, Byblos, Jouni, Kelowna, Las Vegas, Limosol, LA, San Diego, Phoenix, NYC, Portland, San Felipe, Tijuana and Vancouver—though you may not be able to recognize them. The tape offers fragments of those passages—a woman’s hand brought to her chest, dark glasses settled onto a table—gestures which produce a physical closeness, and then a visceral pulling away and separation. The skin is peeled away to only to reveal absence. Throughout the tape there are references to personal and political aphasia, it’s impossible to speak about these moments in a language we understand, so we develop another language in order to have speech. This process involves anxiety, distance and separation, moments of empathy and connection, love and pain, it’s a real mélange. A relationship was a familiar way of looking at alienation, you can get so very close to someone but how deep do you actually know them?

MH: This tape is stunning and necessary, a beautiful lyric which restages a relationship across a fragmented landscape. It’s all so very beautiful, can you talk about beauty? Is beauty a political subject, or is it possible only when talk of politics is retired? Can we afford beauty, does it clarify or blind?

JS: You have to have beauty. Trying to describe it is almost futile, and problematizing it is necessary. I want to make pleasurable and engaging and sensual tapes, I want to draw people in. Although the work may be painful, there are moments of visual pleasure, but you can only get so tactile with videotapes… it is very difficult to work with them beneath the skin, the surface of video is always the starting point, but this impermeable layer must be scratched away to get beyond it. Beauty is a form of nourishment, if there was a Canadian Food Guide which listed the five essential ingredients to live, it would have to be included. I’m not talking about conventional attitudes of beauty but a richness and complexity of life, incomprehensible to a large degree, but very rewarding. Moments of the sublime or the awesome when you’re encountering nature or moments of sensual pleasure or visual pleasure. Why do I weep when looking a painting of Monet’s piles of wheat in a French winter field? What’s with that light, what does it draw out in you? It’s the layers upon layers upon times of reflection and connection, the meditative, the inexpressible, these things connect to your life and deeper to past lives, next lives, other lives, that’s what beauty is for me.

There is a caveat however, as in untitled part 3b: (as if) beauty never ends.., the notion of beauty is negated with the “(as if)” segment of the title, ‘as if’ meaning ‘of course not,’ beauty is subject to ending like any aspect of life, as it requires a subject to engage with.

MH: In untitled part 2: beauty and the east (50:15 minutes, 1999, (2003) a medley of voices opine about eastern European identity, borders and nationalism in the former Yugoslavia after the NATO bombing. One talking head follows another. There is a distinctly erotic subtext in this work, there are so many beautiful women speaking, and they speak so well, with such precision and clarity. “It is very interesting not to believe, not to share illusions any more.” “I can’t identify myself with a national state.” “Some people are only an image, others can think and talk.” On the one hand this tape is all talk, and on the other, the return of the repressed. This tape is ripe with longing, with a need to have a body, to become a body, to embody these ideals and this history perhaps. Can history also be the story of a romance?

JS: In fact, all of the quotes above, if I’m not mistaken, are made by men, whom you could also say are beautiful. The body politic… is this the body you are conflating with the sensual body? Beauty, as I have described it, is such an oblique, subjective, abstract thing, perhaps it suggests possibilities, or hope, a yearning for another state. The nation-state is a romantic notion, all too impractical and forced upon. Its dissolution and reconstitution can likewise be seen that way. The narrative of history and the narrative of love, both are constructed fictions to live for or with… it seems both are necessary for hope.

MH: untitled part 4: terra incognita (37:30 minutes, 2005) is a commissioned work. Can you describe how it came about?

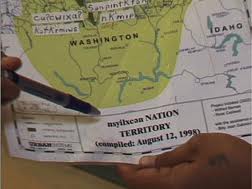

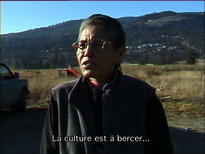

JS: I’d always wanted to make something in Kelowna, that’s where I was born and raised, then the opportunity came up. The Alternator Gallery won a public art competition offered by the City of Kelowna looking to celebrate its centennial year of incorporation in 2005. The gallery’s proposal was to invite five emerging artists to make five minute videotapes, and two senior artists to make fifteen minute pieces about an aspect of the area. Proposals for the five minute pieces would be juried, and for the senior pieces they invited Dana Claxton and myself. These would be put together on a DVD compilation and released as a commemorative disc. For me, the foremost thing to feature in the compilation was First Nations’ voices from the area, I wasn’t sure in what way to approach that. I called up Dana who is a Lakota (Sioux) artist from the Prairies and asked if she would be interested in collaborating but she declined and said you go ahead and do it. Initially I proposed a project to the City that would combine First Nations’ histories and immigrant stories from Kelowna and the (Okanagan) Valley. Like all my projects, once I started taping it took on a life of its own.

My grandparents emigrated to the Prairies from Lebanon in the early 1920s, my parents grew up in South Saskatchewan before they left their farms and went to Quesnel and then the Okanagan to raise a family. In this project I hoped to be able to tease out and confront some of the geo-political implications of colonization, settlement and immigration. There were different periods of encroachment, with people arriving from the late eighteenth through the nineteenth century for a variety of reasons and with different expectations; how do First Nations of the area (the Syilx) people view the period before contact, at the point of contact, and afterwards?

For a few years I had been running art and video drop-in workshops with a collective I started, desmedia, in the downtown eastside of Vancouver where I met Warren Wyss, brother of Cease Wyss, a Squamish filmmaker/media artist. Warren relocated to the Okanagan working with peoples’ sweats, on recovery, part of a healing circle. I headed to Kelowna in February of 2005 for ten days of shooting and hired him to do second camera. He lined up several people he knew for us to visit. I also went through official channels calling the band offices and met a few people that way. After the taping of the conversations started, I realized it didn’t make sense to combine the Native and non-Native stories, there was too much compelling material and the need was so great to present the Syilx (Okanagan) position however best I could. Their stories aren’t known at all, it was imperative to have them as a principal part of the compilation and embraced as part of Kelowna’s history, albeit a neglected part in most of Kelowna’s eyes.

Whenever I start a videotape or get invited to produce a new project I try to figure out what the most critical issues are to be involved with in a local context. If I’m going to devote my time to a specific situation, I want it to have resonance, like in South Lebanon, what were the crucial contentions? Who are the figures to represent the essential areas/fields of representation that I want to feature? After being there for a while you figure that out, you shoot and gather and listen and learn. I make annual trips to Kelowna and nearly all of my family is still there so I had a sense of things. When I grew up it was basically an apartheid state, it still is, like a lot of Canada. The only Indians you meet are usually the disenfranchised urban natives on the street. You don’t really have a lot of encounters with Native culture unless it’s ceremonial, for consuming at a festival, or an opening dance at a conference. I grew up on one side of the lake, when it was colonized the settlers pushed the Indians onto the worst land and took the most fertile areas. The actual town site of Kelowna was part of an area that had been left as a bears’ habitat, it was sacred land and the Natives respected the bears and left this space for them, rarely encroaching upon it.