Carl Brown: Painting the Light Fantastic (an interview) (1990)

Carl Brown is a documentary filmmaker, though his work appears a far cry from the newsreels and illustrated lectures Canadians grew accustomed to during the Second World War. Retreating from an examination of the public sphere, he has fashioned a unique form of autobiography which seeks to convey emotions, not events. To this end he has dismissed traditional film laboratory procedures, and turned to his own basement darkroom. There, he develops his work by hand, pushing strips of motion picture film into glass jars filled with chemicals of his own making. Once the image has been developed, he begins to work on the surface of the material, adding coloured dyes and bleaches, in order to heighten the expressive impact of his pictures. The result is a fantastically coloured rendering which narrates the subtext of everyday events. Working alone with little public attention, Brown has fashioned a body of feature-length work whose “art for art’s sake” directives are among the most esoteric in Canada. His documentaries of perception explode across the screen in colours that would make Disney blush, transforming even the simplest of objects into teeming washes of longing and despair. Brown’s painterly vigils often conjure minds at the end of their tether, and mark him as a unique figure of the Canadian fringe.

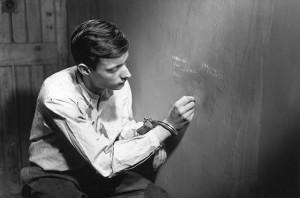

CB: I studied film at Sheridan College for two years before heading out on my own and a couple of moments stand out. I was working on a film called Mine’s Bedlam (8 min b/w super-8 1981) and had prepared an elaborate script and storyboard just as we’d been instructed, and scouted locations and found actors. But when we got there, it was so cold the register pin on the Bolex froze. There was a dead pigeon lying in pieces on the ground, and we imagined this had been done by human hands. Here was the horror my script was trying to induce artificially. That’s when I threw away the script and I’ve never worked with one since. I just started responding to what was going on in front of me. It brought me back to a time when play was integral to existence.

I thought I was getting away with something because there was a lot of work I didn’t have to do anymore — the kinds of things people did before starting a film. Rehearsing. Acting. Writing. That became irrelevant. But we’re raised in a literary world where “proper” ideas are realized on paper. If it comes out of you through your eyes and onto a screen with nothing in between, there’s got to be something wrong. All I was doing was communicating the feel of living in a moment, which is what an artist should be doing. Words had nothing to do with it. I’m a conductor for the present; light passes through me and comes out the other end for people to see. When I got the footage back, the pin didn’t hold the images in alignment so I didn’t know what I was looking at. By all conventional standards this footage was junk, a complete waste. But one of my teachers came in and loved it, and that was a turning point for me — to be able to trust what I’m seeing, not what I’m told.

MH: How did you get interested in working with the film’s material?

CB: I loved the immediacy. You have this colour red that you want to see on your canvas. You see it in your mind and your hand puts it there. If I had to send my footage to a lab and look at it a week later it would be cold for me. I want to process my footage immediately after shooting; it’s part of the same gesture, the same present.

MH: Why not turn to video for that immediacy?

CB: Video’s not physical. It’s not art. Art is something additive or subtractive. Video is video — the signal doesn’t change. In video the surface and the image are separate. How can you respond to iron oxide particles? I can’t relate. I finally realized that it’s alchemy I’ve been involved with, the conversion of silver halide particles. Silver is a precious metal which I make even more valuable by turning it into a light that no one else sees but me.

MH: Tell me about Urban Fire (15 min b/w 1982).

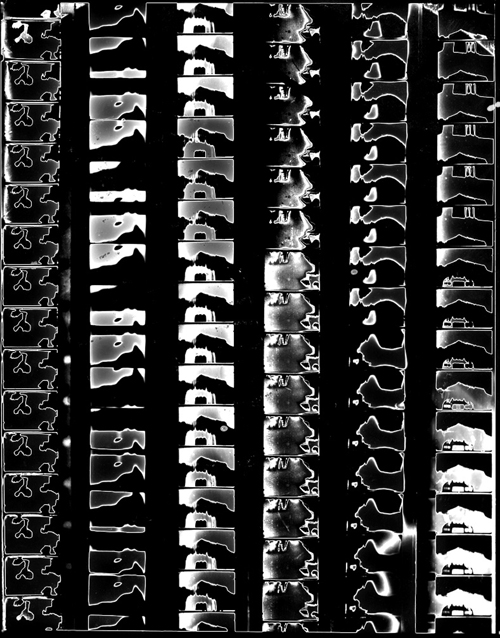

CB: It’s a succession of optically printed loops which develop a series of themes and variations using handprocessing techniques on high-contrast black-and-white film. It was the beginning of my work with film materials. I’d overheard an instructor talking at school about reticulation — he said it was impossible to achieve in film. Reticulation is simply the cracking of the film surface. The initial effect is like breaking into a mirror, separating the pieces, and looking into it. So I boiled some water, poured it over the film to soften it, drained it off, threw some baking soda on it and stored it in a freezer, like a cake. It wasn’t exactly reticulation but it didn’t look like it used to. Then I put a six-foot length of this onto the optical printer and began to shoot variations. Each shot in Urban Fire is a realistic image which I took through various processes, like sabbatier. Man Ray was the first to do that. His assistant was frightened by a mouse in the midst of processing, so she turned the light on. Then she shut the lights down, figuring the print was ruined. What they found instead was a thin line that ran along the silhouette of the picture and a shifting of tones. Sabattier: Born out of accident. I used HC110, a thick replenishing developer which works very slowly. I could control the extent of the sabattier just by watching it because the process lasted so long. Urban Fire developed out of this play of materials.

MH: Why the biblical intertitles and the Genesis quote at the beginning?

CB: The difficulty of speaking about a work made so long ago is that it has a coherence in retrospect it lacked at the time of its making. I was just struggling through it then. If I’d known why at the time, I probably would have done something else. This film was my beginning. Hence the Genesis quote at the beginning. I changed as a person after this film. I went into film school wanting to make feature dramas, but Urban Fire snapped me right off that track. Even though the images are completely abstract, the film’s a personal documentary. It represents my feelings, my calm and storm and bombing and fire. It set me up for things to come. I started to realize my greatness. I know enough about history to understand that when people like or hate something a lot, it means I’ve done something important.

MH: It begins with a series of almost skeletal drawings or blueprints. These drawings cycle and circulate in preparation for the film’s central image: the bombing sequence.

CB: Those are the reticulated images pulled out of the baking soda.

MH: The film builds toward this sequence of annihilation, then proceeds to show its effects in sections entitled “The Fire” and “The Aftermath.” Both these sections seem an examination of ruins and continue to cycle images transfigured by their formal treatment. The process of destruction that the film describes is obviously related to the film processing itself, and I couldn’t help wondering why. The biblical trope suggests that there’s something wrong with this place, hence its destruction. The newly built world of Genesis is continually threatened with annihilation through floods and storms, as if the shape of this race needed to form more solid roots before beginning the task of its own history.

CB: Urban Fire showed all the changes I went through that year: marriage, the end of school, and a complete disconnection with my family and my wife’s family. The film shows this new perspective — the destruction of who I was and the rebirth of someone richer. Everything in my middle class upbringing said that making films in this way was wrong. In order to make them, something had to change.

MH: What happened after you got out of school?

CB: I left in 1983 wanting to make a film about mental illness. At the time I thought all my work had to do with the difference between normal and abnormal. I wanted to deal with issues of documentary filmmaking. I’d gone to the Grierson Documentary Seminar and met a lot of people who weren’t very good filmmakers. I felt that traditional notions of the documentary were finished and I wanted to breathe some life into this genre. Then I needed a crew, someone to shoot and do sound. Steve Sanguedolce and I went to high school together where we made some films. He’d made some short commercials in college and had a good eye. Randy Smith had this $25,000 synthesizer which he never touched. They both lacked focus, but they were keen. This was my first experience of trying to get the energy to move through three people. And in order to get us through a two-and-a-half-year ordeal, there were certain things I had to do. I’m not saying I would do it now, but I did it then to make that film. That’s why the confusion came in over authorship, because Steve believed he was making the film with me. But he wasn’t. He was shooting my film. Randy did the sound.

MH: This was just after government cutbacks led to the closing of a number of psychiatric centres, which effectively pushed a sizeable population of ex-patients out onto the street.

CB: Yeah, so we began by visiting various psychiatrists and city councillors to gain support to make the film. I went to the drop-in centre run by “On Our Own,” a self-help group for ex-psychiatric patients. They called themselves exinmates. They told me about the kind of injustices done to them, like receiving electro-shock on the wrong side of the brain so you lose all ability to read or write, or patients dying inside the hospital, or the ones they let out who are found frozen to death. Very powerful stuff. They needed an editor for their newsletter, “The Mad Grapevine,” and when they gave me the job, it was the first time anyone had held it outside the group. The newsletter had 300 subscribers, all ex-inmates, so this was a unique opportunity to meet and talk with them. I’d written a poem a couple of years before which I included in one of the issues. It was called “Marco Juranovic.” I’d met him at Thanksgiving and he wanted to be the Prime Minister. He was a bum on the street. I went home and wrote about him. The poem had all the usual images of a psychiatric survivor — being frozen in a transit shelter, snot running down your face, that whole kind of pain. It caused an outrage because it turned out there really was a guy in the membership named Marco Juranovic, the guy I’d met two years back. I put it in the newsletter because I thought it was a good poem, and I guess it was because it really hit home with a lot of people. The whole time I worked at the “Grapevine,” I had a running argument with one of its co-founders, Don Weitz. He was always asking, how can you make a film about mental illness if you’re not mentally ill, if you’ve never gone through the experience? I just kept talking with people, getting to know them, gaining their trust. I worked there eight months, dead broke with no grants. We went to two hundred foundations and agencies. They all turned us down. Then I said let’s go to Canada Council. I submitted Urban Fire and Mike Snow was on the jury. He loved the film and I got the grant. That’s when the film began.

Randy, Steve, and I drove up to a gold mine I used to work in Red Lake. My cousin owns an island up there, and the plan was to bring up sixty hits of acid, spend a week, hash the film out, and bond the three of us. We stayed five days and I finished most of the acid in the first couple. Randy was pretty fucked up. After looking at these water bugs, he decided he couldn’t work with Steve. I was trying to balance everyone out — something I didn’t have a lot of practice with. There was a lot of pain and I did a lot of things. I was twenty-three when I started the film. It was finished three years later. The scope of the film is pretty wild for someone that age. It’s because I have this ability my father has: to disconnect and continue. So I disconnected and made my way through the film. My old man never goes back to try and pick up the pieces, and after this film I needed help to put it all back together. But I always go back. It took a year-and-a-half before we got the first grant — $12,000. Then we started shooting. We were so pumped that once we got back from Red Lake it took less than two weeks to shoot and a week to cut. We worked like parts of a machine, always knowing what the other was thinking.

MH: Can you describe Full Moon Darkness (90 min 1984)?

CB: The film journeys through a number of monologues of anti-psychiatrist Thomas Szasz, a priest, and four exinmates. After each interview, a visual translation follows which leads the audience into the next level. We peel successive layers away until we’re at the heart of it. But in the end, everyone still has to make up their own mind. The descriptions of the drugs and electro-shock are horrific. But there’s still a lot of people who create pain for others. How do we reconcile these two?

MH: Your work since Full Moon retreated from social concerns. Returning to Urban Fire’s narration of materials, the ways of their making have been stubbornly artisanal. It’s all just you, a Bolex, and your bathroom darkroom. Tell me about Condensation of Sensation (73 min 1987).

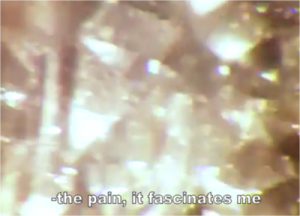

CB: Condensation is an aggregation of moments that appear like crossroads or intersections. The moments when things happen to you. Like driving in my car and finding out Ermano Bulfon, the priest in Full Moon Darkness, had just died of brain cancer. Then the rear wheel blew out, and I almost wiped out three cars, a telephone post, and a schoolbus. The film’s not interested in recreating this event, but in rekindling the feel of what it was like to be there. I don’t want my film to exist in the past as a nostalgic reminder of the way it was, or as a record. I want people to feel the present as they’re living in the theatre. To feel things you pass every day without noticing. I work on the image, reprocessing the surface to make those things magical again. There’s a shot of houses on my street that has a frenzied jazz feel because of the gestures of camera and emulsion. Everything moves: the film, the sound, your eye, and everything moves in rhythm. That’s what Condensation is all about: it’s a building sensation that gets spilled across the screen.

MH: How did you get involved in colouring film?

CB: It all started with sabattier. Even though it’s a graying effect with line, there’s colour there. These colours are made by converting film’s silver halide into another colour. So what other colours could you convert silver into? That’s when I got into toners, started to play with them. I never went by the book or read the instructions. The film surface is made of silver halide. The toners attack and convert the silver halide particles into colour pigments which change the blackened silver into colour. Tinters affect the clear areas of the image while toners affect the dark areas. When I started applying this to film I saw colours I’d never seen before. Ever. It looked like something between psychedelia and Van Gogh. I used to use an old wine jug that would take a hundred feet. I’d lay in a hundred feet, apply a colour, then take it out, hang the film on some wire, and put a hairdryer underneath for about half an hour. Everything’s done at home in the bathroom. Now I have a jug I can process and colour 400 feet at a time. I’m working on Mike Snow’s new film, processing all the footage. So I bought a new jug which has a bottom like a brandy glass so I can spin the toners around the bottom of the jug — it gives me more control. I can determine how the toner hits the surface of the film and what kind of motion it’ll create on the surface — all depending on the movement of my arm. You can increase motion on the film surface by using what I call “depravity of toner.” Applying used developer will overdevelop certain spots and underdevelop others. But the process moves so fast that when you view it on the projector all you see is the processing itself moving across the surface. Then you could put this in a sepia bleach which takes out some of the toners, or use rubber cement to mask off areas of the image and let it soak for a month so the toner will show through certain areas. Then you take the rubber cement off with cleaner and begin again with another toner, which you can stroke on with any number of implements. It’s like a witch’s brew. Often you lose valued footage, but that’s part of it. I might work a year on a piece of footage and put the last touch on it only to watch it fade into nothing. That’s happened a few times. Condensation began with a series of loops I cut from outtakes and found footage. I got fifty or sixty cans and gave each loop its own can and then started adding a bunch of shit — like bleach, or old tints, or dye mixtures. I let them sit eight months, and these became the basis for the film. Originally I was going to put them all on the optical printer, each loop had its own title, and the film would run nine hours under the title “The Dissection of Mental Semantics.” But I abandoned the printer and made Condensation of Sensation instead. “Dissection” was conceived as a kind of gallery work, and I’d feel comfortable showing most of my work that way, just running in a room. The viewer should be able to come in and out whenever they want.

MH: Do you feel your work suffers from being shown in movie theatres as opposed to galleries?

CB: I think so. People shouldn’t be forced to stay with something so foreign to them. The sound and image are very intense. If it takes me two-and-a-half years to make a film, it doesn’t seem to me unreasonable that it would take someone that long to watch it.

MH: When Alain Resnais made Last Year at Marienbad, he left instructions with the projectionist that the reels could be run in any order. Could you live with that?

CB: All of my films are on two reels. But if they were on ten smaller reels, that would be all right, showing ten paintings in different orders. By pulling my work apart, someone could find their own way of watching it.

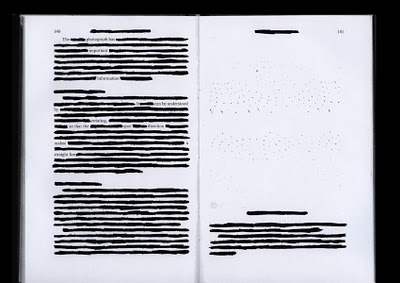

MH: Condensation is a kind of materialist psychodrama; its protagonist is a faceless blank wandering in a multi-coloured garden. Psychodramas often turn on this lonely figure who attempts to negotiate the divide between his/her own prelinguistic solitude and some kind of social order outside. Condensation’s disavowal of language is a move away from the narrators of Full Moon Darkness whose voices key the film’s changes. It enters a different sort of documentary register, a documentary of consciousness. In a film this length it’s difficult to think of many that are wordless.

CB: I wanted to move away from language because words take away from vision and emotions. From the time I was five years old I’ve been reading. But those books and the words that come out of my mouth don’t have anything to do with my work. This interview has nothing to do with my work. I’m a filmmaker, not an author.

MH: Tell me about Re: Entry (87 min 1990).

CB: Both Condensation and Re: Entry are about the dis-ease that drives one to solitude. I had to go inside to uncover the fears that were stopping me from moving, to find out how I’d lost control. I did this one acid trip and it affected me for four years. We were tossing the frisbee when Randy ran over this kid and landed on his arm in the same way I’d broken my arm as a child. The angle was the same. Somehow I’d disconnected myself from that time, that pain, and in the moment I saw the child falling, it all came back. I went back home and saw that all my clothes were filled with holes and it made me afraid; it meant I’d stripped away everything. There was nothing left. This cloud of reasonless fear settled in and I thought, okay, I’ve got eight hours to wait and it’ll be gone. It lasted four years. A long trip.

Re:Entry was a response to looking at things and perceiving them in this frenzied and frightful way. Although my actions as a person were strong and aggressive, they were just a mask for the fear inside. Going on the subway might provoke an anxiety attack, so I wouldn’t go. I couldn’t drive a car for a while because it would start happening on the freeway, and I’d have to pull over immediately. I wouldn’t do anything that might provoke one of these attacks until I was virtually in the house all the time. Then it started happening in the house. I got invited to stay in an artist’s colony in Banff. It was a chance to head out into the woods and deal with this stuff. But it all started happening again in Banff. You can tell by looking at the footage — I’m scared shitless. A lot of that stuff in the forest is like Jason from Friday the 13th. The camera’s only tilting over trees, but all you’re really seeing is my terror. My friend Paul came out to visit, and we drove all over Alberta, shooting the Badlands and the Hoodoos. It’s pretty bleak out there. That was the end of the trip. When I came back from Banff I felt I’d peeled off something; I’d left something behind I didn’t want. The acid trip had shed there, had its last gasp there, which you see in the film. So I got back to Toronto and made preparations to shoot the swimmer. I waited a month for the right light, and we shot it in an afternoon — Paul swimming back and forth in a pool. I realized later that he went through everything you do to get your Bronze Medallion, the one that allows you to lifeguard. The way he looks in the water is how I felt — the freedom and fluidity and expressiveness. I’m not saying I don’t get anxiety attacks anymore, but they don’t rule my life. That was my re-entry, re-entering the fears that make you the person you are, and I brought a camera along to show the changes.

MH: Could you describe the film?

CB: We see images of the swimmer diving into the water to begin his journey, which takes him through the fields and mountains of Banff. There’s a horrible recurring image of something that’s dying and decaying. It’s from a Lorne Greene nature documentary. I used dye baths to tint images of a baby alligator being eaten by flies as it’s coming out of the egg. The mother’s looking on, but the child is already dead. On the soundtrack a voice reads from a relaxation tape; it’s very soothing and calm. It came from the bio-feedback therapy I was doing where they teach you how to relax. But who can relax with all this shit going on? So the sound and image never come together, and the swimmer’s trying to make his way through it all until there’s no water left. He’s just swimming through the white light of the screen. The first reel ends with his exhaustion; he almost can’t go on, so he drownproofs for a while, almost still. He needs to rest.

The second and final reel begins with Paul’s recital of the opening of Foucault’s I, Pierre. It begins, “I, Pierre, having slaughtered my mother, sister and brother…” and goes on to explain why he did it. This sets you up for the second reel. You see the countdown leader, then a house with a swaying camera motion towards a door, then a guy hiding, then back to the house, then it cuts back to a wooden voodoo doll being thrown into the water. Then the voice begins to repeat; it lowers in volume, so the rest of the film is like his testimony in a way. The swimmer returns. He’s regained his strength and moves again through the Banff footage, but now there’s a sea of emulsion to swim through. A series of superimpositions follow: a child playing supered with a brick wall; old people lawn bowling supered with other old people walking down the street. It’s a return to the city, a return of the social. The sound builds to a fiery climax because all this talk of relaxing only covers over the fire that’s inside the swimmer, that everyone has. He leaves the pool, begins to burn, and the film ends. Whenever my work starts to get shown, I hope people connect with that moment, recognize that fire inside.

MH: You exercise a high degree of control over your images, yet you’ve always given complete control of the sound to others. Why?

CB: I felt that when the paths of two strong independent forces crossed, it would be magical. I couldn’t hope for that to happen if I imposed a structure on them. Collaboration is where no one is telling anyone what to do. We’re both doing groundbreaking work — so let’s do it together. I’ve worked with Rik Dekker, CCMC, Kaiser Nietzsche and Mike Snow. After working with Steve and Randy so closely, I didn’t want to go through that again. So I get together with the sound folks, we talk about the work, we talk about each other, they play me some sounds. I say, ”Hey I like this, I like that.” They take a gauge off me. Or maybe I say, “Could you bring a trumpet down tonight? I love your trumpet playing.” That’s it. I like working that way. I’ve been able to work with very talented people, so there’s no need to do sound myself.

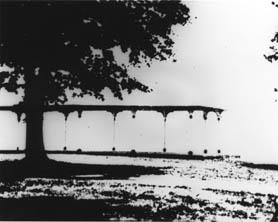

MH: Tell me about Cloister (34 min 1990).

CB: I’ve shown Cloister once — in the bar at the Experimental Film Congress. All the Europeans stayed and all the Canadians left. [laughs] Cloister comes out of the isolation of my living — I live and work in a small world. It took me a day to cut the loops. I worked with them for two days on the optical printer, another two days to process. It took six days to make a half-hour film. I don’t know why it happened so fast. It was just before I started working at the post office. All my relations were going well. I had just come out, back out into the light. It happens every time I make a film — I make an effort to be social. I see people and realize that I enjoy it after all. I wanted this film to show the light and dark of my past. It’s my homage to abstract expressionism which knocked me on my ass from the first time I saw it. Klein, Rothko — those guys just blew me away. So this film shows you these small canvasses, 150 of them on film. I used a Laurel and Hardy film, outtakes from most of my previous work, newsreel footage, footage others have thrown away. It’s like a rehabilitation project. All the people I’ve touched in the past ten years are included somehow. Michael Snow does the sound using his son’s toy keyboard and his trumpet. As the film rolls you hear him turn the tape machine on, play something, then turn it off; then he turns it on again, plays something else, and turns it off. It’s a very disjunctive feeling you get when you watch the film.

MH: The images are alternately representational and abstract, showing people in various vehicles of conveyance — cars and bicycles — and a passing surround rendered abstractly. In certain passages the sound follows the image, accompanying and underscoring its effect. In others, it moves completely against the image, as if it were distracted. Most of the soundtrack is simply silent. What I hear in Snow’s sound work is someone listening to the film and responding in a way that’s sometimes audible. The sound of the tape recorder coming on and off makes this dialogue explicit. The first viewer is the ear.

CB: Cloister is the end of a cycle which began with Urban Fire. My next film will be radically different from this work. I came back to the optical printer with this film after leaving it for eight years. Cloister is a recapitulation of themes and gestures that have run through my work for the past ten years.

MH: How much do your films cost?

CB: Mine’s Bedlam cost $250, Urban Fire $500, Full Moon Darkness $35,000, Condensation was $42,000, Re: Entry $38,000, and Cloister $6,000. I never paid for any of my films myself. But all of my films added up together wouldn’t fund a dramatic feature film, or some thirty-second commercials.

MH: Is there an avant-garde in film today?

CB: Sure. I like the work of Phil Hoffman, Chris Gallagher and Barbara Sternberg. They’re challenging the bounds of cinema, they’re working in ways unlike anyone else. I don’t get out enough to watch experimental film, but those are the ones I’ve seen that are good. Avant-garde means a cutting edge. It means taking yourself over the precipice and looking into an abyss and pulling something out of it. The avant-garde are people who aren’t afraid to go an extra step. It means you’re doing something like no one else and doing it powerfully. None of the people I listed are similar in style, because avant-garde isn’t about style.

MH: Some people would insist that any notion of “avant-garde” includes a political dimension.

CB: That’s bullshit. Theory and politics are as fashionable as changing your underwear every day. The work will last, not the politics. Do they really want to make this film, or is it something that’s politically viable? Or politically important? Who cares? Art is about the politics of seeing and feeling. I don’t believe in any of that other shit. Other people decide whether your film is good, bad, or indifferent. I’ve been making the same quality of work for ten years, but all of a sudden people think it’s okay. I never changed, only the words changed, other people’s words. There are only a few good directors in Hollywood and just a few good avant-garde filmmakers. Most of the work being done anywhere, regardless of genre, is trash. For the person who doesn’t know avant-garde film, they’ll come see it and hate it. They’ll take that program to be representative, and they’ll never come back. So we’re hurting ourselves.

I remember going to the Funnel Experimental Film Theatre and seeing a lot of garbage, because the members had a corner on what got shown, which was mostly their own work. So here I was in my infant stages, crawling as an avant-garde filmmaker, and I was throwing up after seeing this crap. People who didn’t know anything about avant-garde film knew that the Funnel was a weird place to go which showed lousy films. Here I am an avant-garde filmmaker, and I won’t go to the only theatre in the city that shows this work because it’s awful. Then it closed. Toronto is the most thriving art community in North America, bar none, and we don’t have a place to show our films permanently. That’s absolute bullshit. Most of the best avant-garde film work in this country is happening here and we can’t get it on a screen. You get two lines at the bottom of an art review. You get hardly any recognition. Avant-garde film is like a pariah, like having leprosy. Even avant-garde music doesn’t have it as bad, but film is where the most important work is being done in this country.

MH: You had to wait two years after Condensation was finished before it was shown. Full Moon has shown twice in Canada. That means your three feature films have had four screenings altogether.

CB: I knew that what I was doing was very different. It was radical work and it was long. So I didn’t expect returns. I don’t think about people looking at my work. So I wasn’t devastated when I didn’t get screenings. I showed it to a few people who liked it and that was enough. When you’re developing a genre or style you don’t expect people to come clamouring up to you wanting to show it. I thought that might start happening when I was forty. What bothered me was that the films being shown weren’t high quality. It’s never crossed my mind that I’ve had two screenings in this city in ten years. As long as I can do the work. It was important how it felt for me and whether I got another grant that would allow me to make the next film. Because of the amount of media, no matter how much you hide, someone is going to lift up every crevice of the art world to find the new thing. At some point they would come across me, and as long as I worked on my skills, I would know how to respond whenever that happened. When Arbus showed her work, they were spitting on her. People stormed the projection booth when Snow was trying to show his stuff. There’s lots of examples. I’ve just never taken an interest in anything beyond my making. That’s just starting to change now.

MH: Would more money improve your work?

CB: I don’t think a million dollars would make my films any better. I could try a few more things. I could be more wasteful, but frugality has allowed me to make some discoveries. The glimmer of the individual creates an image of what people see on the screen. That’s what people want. But they want to package it. Sometimes you wonder about guys like Peter Mettler or Bruce McDonald who have ability and talent. How much of what they feel manages to survive the machine of big-budget filmmaking?

MH: Why won’t you get that money?

CB: Because no one is going to give me a million dollars to sit in my basement and tone film. Besides, I don’t think I could spend a million dollars on a film. I felt Peter Mettler and David Lynch were great filmmakers, but they entered that system and got chewed up. Not because they got stupid overnight. It’s just too big to fight. I was completely drained during Full Moon Darkness working with two people. And on a big film I’d expect that kind of commitment from my gaffer and my best boy. I’d go insane.

MH: Is there anyone who has made a big difference to your work?

CB: Mike Snow’s been a big influence. As an artist, you don’t have any kind of background information; it’s not like a doctor where you’re an intern first. As an artist you just do it and hope that the way you’re going is all right. My whole purpose is not to burn out and die. And that’s one of the things he’s taught me, in a way, how to think young. In order to get through a lot of pain, it’s important to have a sense of humour.

MH: How would you characterize the Toronto film scene?

CB: When I was starting out ten years ago I always felt like I was part of a new movement in art. Now I don’t know. I don’t deal with filmmakers apart from Phil Hoffman and Mike Snow. It seems to me there’s a lot of backstabbing. It’s affected my ability to show work because I haven’t aligned myself with anyone. I’m a renegade. It’s been a conscious decision which has helped me to develop a strong style. Every medium has its backstabbers, but when you find something as specialized as avant-garde filmmaking, you’d think people would come together. Our voice would be stronger if we spoke together. Now it doesn’t seem as if that’s possible. I’ve contributed to this. There’s people I don’t talk to, but because I’m involved in more than one medium, I can stay out of the soup. Everybody I see who’s in avant-garde film is so tightly wound up in it. It’s a very tough life. I also make holographs and photographs. The only way to survive as an artist is to do everything. The artist is like a cockroach — we have to be able to eat anything in order to survive. You try to kill us, but we keep coming back.

Carl Brown Filmography

Mine’s Bedlam 8 min b/w super-8 1981

Urban Fire 15 min b/w 1982

Full Moon Darkness 90 min b/w 1984

Condensation of Sensation 73 min 1987

Drop 4 min silent 1989

Cloister 34 min 1990

Re:Entry 87 min 1990

Sheep 7 min silent 1990

Brownsnow 134 min 1994

Air Cries, “Empty Water” (The Trilogy)

Misery Loves Company 60 min 1993

The Red Thread 60 min 1994

Le Mistral, Beautiful But Terrible 120 min 1997

Originally published in: Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada, ed. Mike Hoolboom, 2nd edition; Coach House Press, 2001.

Brownian Motion: The Films of Carl Brown (1989)

Carl Brown is a young Toronto filmmaker hoping to celebrate his thirtieth birthday with the release of his third feature film Re:entry. The term feature is somewhat of a misnomer here, for apart from an emulsion bent on filling film’s infinite rectangle for an hour and a half there is little his movies share with those theatricals whose homes depend on concession stands to pay their way. For reasons of material necessity as well as the extreme compression and complexity of expression, artist’s film is usually short—most work is less than half an hour long. Brown’s decision to work in a feature length format, his aggressive assertion of film’s material base and his propensity for abstraction have made him an anomaly amongst Canadian film artists whose work in the past twenty years has been largely representational. Virtually unknown in the very city where he continues to make work, he has watched with a growing sense of irony as his framed film stills have sold in a succession of photography exhibits while the same images in motion continue to be overlooked.

(author’s note: Twelve years after this was written, Carl’s still not a household name, his gallery went up the dealer’s nose, and the features have kept on coming, the last couple in double-screen format. But faced with the end of chemical cinema, filmers round the world have re-embraced the material, difficult to attend fringe events these days without seeing the results of someone’s bathtub efforts, so in a sense the scene has ‘caught up’ to Carl. Though few have rode the horse for twenty five years, never mind the sheer volume of work.)

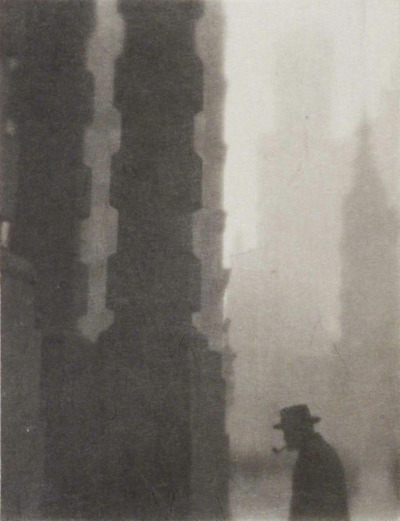

Brown’s first feature Full Moon Darkness (90 minutes 1985) imaginatively linked theology with the rise of psychiatry and provided in its extended interview sequences and expressionistic interludes a mosaic of all that psychiatry had left behind: the homeless, the academic dissenters and those for whom shock treatments had failed to take the place of history. Shot in a brooding black and white, Full Moon‘s blend of high contrast print film and full toned camera stocks recalls the anxious Gothic horror of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, reset here in documentary prose. Caligari is similarly framed by the psychiatric confines that have housed many of Full Moon’s subjects. Like Caligari, Full Moon oscillates between midnight and high noon, between the gestures of cruelty and civilization, convention and intervention.

The narrative spine of Full Moon is transported by lengthy sync sound interviews with six people. Anti-psychiatrist Thomas Szasz speaks about the myth of mental illness. Father Ermano Bulfon, clutching a bible throughout, speaks of faith and the need to give oneself up to “this guy Jesus.” He is followed by Don Weitz, co-founder of a self-help group for ex-psychiatric patients. His delivery is angry, pointed and electrifying, decrying the abusive drugging and shock therapy that are the mainstays of the psychiatric profession. He is followed by three ex-psychiatric patients, each describing a personal history framed by correctional institutions. The camera grows increasingly autonomous from its subject as the interviews progress. While it never strays beyond the hands and face of Szasz, the interview with Weitz shows a camera careening over the walls of his apartment, moving in counterpoint to his own poisonous assertions in a fugue of call and response, subject and camera. The filmmaker as ‘director’ himself grows increasingly evident, slowly including clapper boards and questions until barking out the film’s last word: ‘CUT!’

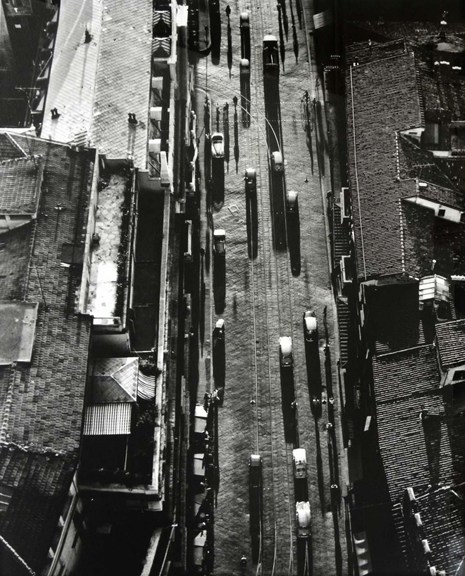

These interviews are punctuated by long impressionistic sequences: a late night street shot until daybreak, a broken architecture of brick, a doubly-exposed walk towards home and most succinctly: a long held-held tracking shot along a snow fence rendered in high contrast, its blackened posts rising and falling in a great broken march of humanity. The film is photographed by Steve Sanguedolce, the film’s co-creator until a bitter series of arguments ended their association. His episodic camera style elegantly enlists its subject in a single, ten minute camera roll; photographed with the same camera North American news teams employed before the advent of video. Sanguedolce’s subject: whether circling an abandoned irrigation ditch or walking a stretch of snow fence is entered as an arena of performance. Frankly expressionist in its diction, the filmmaker moves in concert with his surround, taking up the rhythms of his subject in a camera-led gesture of sympathy and correspondence.

There is an overwhelming sense of urgency about the work’s unfolding, that somewhere between the first words and the last lies a consciousness wagered and lost and won again, slaved to the dissonant cries of this work’s speakers. The film closes with a white gowned poetess remarking from the tree line, reciting a broken prose of reawakening before the credits begin: “through their veins/voltage is increased/the age of reason, IS/…a voice said/freedom/now the hard part begins…”

Brown’s second feature Condensation of Sensation (73 minutes 1987) is a materialist travelogue that documents the process of perception itself, what Brakhage has called “mind motion.” An intermittent montage of 60s commercials punctuates the wanderings of its lead—a blank-faced boy wander who struggles through a garden of unearthly delights before lighting on a water’s edge park. Condensation is generously furnished throughout with the broken iconography of Roman Catholicism—churches and religious processions struggle for visibility through the torn emulsion of their development. The proliferation of crosses challenge viewers to secure the image within a design of their own making, a design the filmmaker suggests is finally theological.

“Language is the guarantor of orthodox faith because it authenticates the specificity of the Christian confession… this punctuation, which we know to be the condition necessary and proper to all language, reigns… cutting up, dividing, combining every strictly semantic operation designed to combat relentlessly the vague and the empty… Doesn’t all poetry consist in liberating the word from its content? Doesn’t all philosophy consist in putting it back?” Roland Barthes, Sade/Fourier/Loyola

Brown’s work shares with abstract expressionist paintings of the fifties an aesthetics of silence, or at least, an insistence on the paucity of the word. Even Full Moon Darkness‘ extended interviews are underscored by the dark continent of the unconscious, a continent Brown believes is not structured like a language. In all of his work he strives to overgo an alphabetical frontier—to pass into a realm of the senses in which linguistic understanding is beggared by a surplus of expression. Stan Brakhage, the grand American avatar of silent cinema, once declared that the work of Hollis Frampton strained cinema through language. Of Brakhage’s work and Brown’s both we might declare the reverse: that language is strained into speechlessness by a cinema tied to the synapses, the optic fibers, the central nervous system. Both filmmakers have taken up and extended the diction of abstract expressionism, with its emphasis on gesture, performance and the redemption of a prelinguistic universe.

In Condensation of Sensation the filmmaker has applied himself to the surface of the film, soaking its small strips in dye baths to produce a hallucinatory palette. Passed through successive generations of printing, painting, sabattier, reticulation, gluing and toning—the film provides a kind of encyclopedia for hand processing techniques. Condensation‘s benzedrine montage is periodically interrupted by a crawling male figure who wears a mirror in place of his face, reflecting some of the teeming wonder of his surround. This figure weighs anchor on the plays of light and shadow that precede, coding them as ‘subjective,’ grounding them in the internal chemistries of this wandering star struck. His journeys come to no precise end however, and begin likewise in the middle, his mirrored visage recalling Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon—signaling this film as a psychodrama of emulsion.

The soundtrack is an improvised jazz track performed live by avant garde music collective CCMC—a group including Michael Snow, John Kamevaar, Casey Sokol, Nobuo Kuboto and Al Mattes. The feverish improvisations and virtuoso performances beautifully double the movements of the film, which close finally with an extended shot of a lakeside run, tinted yellow. Members from CCMC have already begun work on Brown’s new film, entitled Re:entry. While Re:entry remains a work-in-progress it looks to take up the imaging strategies of Condensation. The blank faced traveler has become a backyard swimmer and his surround the dyed wilds of Banff, Alberta. A diverse audio montage of television programs, relaxation therapy tapes and musique concrete percussion will accompany. Making work that may be likened to a moving abstract canvas, Brown continues to reinvent his material base with demands that the genre of documentary be expanded to include the workings of consciousness.

Originally published in:

Experimental Film Coalition Newsletter (Jan/Feb/March 1989)

reprinted in:

Vanguard Vol. 18 No. 3 (Summer 1989)

Millennium Film Journal No. 27 (Winter 1993/4)

Lightstruck Vol. 8, Nos. 3&4, Fall 1996.