- We are all Monsters (pdf)

We are all Monsters: an interview with Birgit Hein (1990)

Birgit Hein was born in Berlin in 1942. She met Wilhelm Hein in 1959. From 1962 both studied in Cologne; Birgit studied art history while Wilhelm studied sociology. They married in 1964 and began joint film work two years later, abandoning their studies. Their first film was accepted for the Fourth International Experimental Film Competition in Knokke, Belgium (1967-8). In the spring of 1968, together with other filmmakers and film journalists they founded X Screen, the first exhibition venue for fringe film in Germany. Their first international success came with Rohfilm in 1968. In 1971 the paperback Film im Underground by Birgit Hein appeared, the first German-language publication on the subject of underground film. From 1973 to 1977 Birgit Hein undertook various teaching assignments. In 1977 they assumed the direction of the film section of Dokumenta 6, staging the exhibition ‘Film as Film.’ They subsequently abandoned formal/material filmmaking and began a performance tour through Germany and the United States. They are recently separated.

BH: The development of experimental film in Germany is very interesting. It started at the end of the 1960s and was called the ‘other’ cinema. By 1970 there were about one hundred filmmakers and later it collapsed completely. In 1968 there was a political movement in Europe and North America along with a new film movement. Some became feature film directors from 1969 like Schroeter, Praunheim, Fassbinder and Wenders, many vanished and a few remained with experimental film: Klaus Wyborny, Werner Nekes, Dore O., Heinz Emigholz, Bastian Cleve, Lutz Mommartz and Wilhelm and I. This was all that remained by the mid-seventies of the people who were making work in the 1960s. Cleve and Mommartz were strong in 1968 but their later work was not interesting, whereas the rest of us, the other five I mentioned, had a very interesting development from formal film to narrative. Then at the end of the 1970s a new generation of filmmakers came, it was a super-8 movement, and they didn’t come from this historical background like we did, with the New American Cinema and so on. They were the media generation, they grew up with television. By the end of the seventies filmmakers also began coming out of the art schools, not many taught it, maybe two or three, but it was another place.

MH: Was the first generation of filmmakers all teaching in art schools by the mid-1970s?

BH: Only Nekes. Others who weren’t that radical got the jobs, you understand? But anyhow, having this teaching in the art schools brought the two movements from the 1960s and 1970s together. I was often invited to do seminars, the old people brought the history back, but these new people opened the film movement. Since the 1980s it’s really flourishing, people have a lot of information through festivals, and a lot of people make work. After a long period there was no Knokke Film Festival any more, and these festivals were a place to come together. Then there were these Berlin people, Berlin was very important, they started the InterFilm Festival. They started cinemas in the squatted houses. Kino Eiszeit was one of these. They started a new sub-culture. I met Jurgen Bruning here in Osnabrück, he had started Kino Eiszeit with others. He was very young and very far out and invited Love Stinks to play in this squatted house and it was like a new life had started, it was just wonderful. This is why I was so angry in Toronto at the Film Congress when people of my generation were saying nothing happened, the movement is dead. It’s absolutely bullshit. Tremendously creative powers have developed in the 1980s.

MH: I think that’s more of an American understanding—that the American project seems to have come to an end, that no similar swell of new works seems to be able to take the place of the old. Their history has a terrible need, it kills everything. But the new filmers in Germany, are they mostly coming out of art academies?

BH: Not only that, but rarely out of film schools. Normally film schools don’t bring out new talent, they make documentaries or drama. If it’s inventive or experimental it comes from the art schools. For instance Klaus Telscher and Claudia Schillinger studied in Bremen, Rotraut Pape studied in Hamburg, Christoph Janetzko, Straacke, Brynntrup studied in Braunschweig, Stephan Sachs in Düsseldorf.

MH: When you started making work in the 1960s, where would you show it?

BH: There was only the commercial market, commercial cinemas, nobody ever thought of presenting something else, so we organized it ourselves. Wilhelm and I and other filmmakers and film journalists made a place called X Screen. Our first screening was in March 1968, renting a cinema for night screenings. Cinemas weren’t going very well so it was easy to rent.

MH: How many people would come out?

BH: Sometimes we had over 1,000 people. I remember Larry Kardish when he came from MOMA with Andy Warhol’s work he couldn’t believe it, and this was the time it was called underground and just the promise of a bare tit would start a line up. Then we showed Ken Jacobs and twenty people came.

MH: Did you receive any money for putting on programs?

BH: No, it was completely private so we also ran porno films. We got money by showing illegal films.

MH: Did you show mostly German work?

BH: No, the first screenings were Vienna avant-garde, then German and American. Everyone came. Very soon after X-Screen started others began in Munich and Hamburg, and more followed. This was long before the community cinemas, the Kommunale Kinos. It was all private initiative when we showed these films in 1968-70, we had to make it a club because of the censorship laws at that time, and everyone had to be a member. When I was in Vancouver in December 1987, all the people who wanted to see the women’s program had to become members so it was the same again.

MH: What are the Kommunale Kinos and how did they start?

BH: In the middle of the 1970s the Kommunale Kinos were established, one after another. People were aware that cinema should be subsidized and film history should be shown. The generation of 1968 was the first film freak generation, the first generation to be seriously interested in film and film history which was completely neglected before. Some of these people got into TV which changed as a result, they showed historical programs, auteur retrospectives… Others remained filmmakers and still others ran the Kommunale Kinos.

MH: Are the Kommunale Kinos like art house cinemas, rep theatres?

BH: Yes, they get some money from the government. German culture is subsidized by the government—theatre, opera houses, none of these places are running economically. So finally after years and years some film theatres are subsidized, some have more money others less.

MH: Were they started by individuals and then the government supported them?

BH: Normally it’s private initiative at the beginning.

MH: Are they spread all over Germany and can you show your work there?

BH: It’s not the only place, of course, because the Kommunale Kinos rarely show independent films, some like it more than others. As well, there are independently run small cinemas which show independent work, there’s a lot of them all over Europe.

MH: But don’t the Kommunale Kinos have a mandate to show German or independent work?

BH: (horrified) No. They decide what they show. The program is completely up to the person who runs it. For example in Dusseldorf the head is very friendly with the French Cinematheque so they run a lot of French films, and they’re friendly with the experimental filmmakers so they have regular screenings while the others may have them only once in a while. The government controls the places only by money, some need income so they have to play popular films, but others are completely subsidized. then we also have these half Kommunale Kinos, maybe they get the rent free, but everything else is their private concern. So there are different models of Kommunale Kinos and the best of course are the fully subsidized. The numbers change. Once there were 120 Kommunale Kinos in Germany which I couldn’t believe, but then you find that some get very little support.

MH: Why would all of them show experimental work? This is always the first work that gets left behind.

BH: All of them were film freaks in 1968 which was a political time, and experimental film was just coming in, and all of them were interested in the new American Cinema. That was the first connection to experimental film. Some had started showing work in 1964. When they got into their jobs some distant feeling from this early time remained. The same people work from the beginning of the cinemas. These people are fanatic, it’s not a job, it’s a life dedication.

MH: What were you doing in the middle of the 1970s?

BH: Nothing. The middle of the 1970s was very dry. This was the lowest point in experimental film for everyone. There was no interest any more, a change in climate. Suddenly people realized they couldn’t live making experimental film and most left. There were about one hundred people in 1969, enormous activity, and maybe five left in 1974. People went into business. Some understood they would stay to make political films, and very few remained to make experimental work.

MH: I’m wondering about the few people left making work in the seventies. Did this common experience of survival show itself in a common style of filmmaking—as if you’d reached the same conclusion?

BH: Not at all. In 1968 when this broad movement came about it was all called experimental, but few really were. We knew that sooner or later most would make stories, and just a few would continue working on formal problems with structural films. The Knokke Film Festival in 1974 was a heavy psychological shock. We didn’t get any recognition with our Structural Studies. Dore O. got the main prize. Her film was good, nice, but again a reaffirmation of the New American Cinema, not the recognition of new ideas.

MH: What is the difference between Structural Studies and the New American Cinema?

BH: It was a completely different kind of thinking, a different aesthetic: the destruction and dismemberment of art. We were connected with avant-garde movements in art and political thinking, trying to discuss society and art through film. Our work was anti-aesthetic and anti-ruling-avant-garde, which is difficult in such a specialized area as experimental film. Then we organized the Dokumenta ‘Film as Film’ exhibition in 1977 and this was the end of formal film work.

MH: How did you see the link between a formal practice of film and a political practice?

BH: The hope was that somehow radical avant-garde practice could affect society. After awhile we understood that what we were discussing was anti-art, and that it would all lead, like Dada or Fluxus, to a discussion within the art frame. What you were destroying could only be understood by the art society. No one outside the codes understood the work. This was the problem of the separation of art and life, you want to get your life with your art but you can’t. So something has to change.

MH: But was there a moment when that wasn’t true?

BH: No. There was a time when people were running into the cinema of 1968 just because they were curious, but they didn’t understand it. It didn’t make a difference. Finally you have to admit that this is not the way to effect political change in society. You have to move towards content.

MH: You made quite a lot of work in that time, what kind of difference did it make then?

BH: It was just a process for ourselves to get clearer. In the end we reached a point of discussion where very few people could understand it. It’s comparable to people working in mathematics and in the end you have four or five people who know it, and it’s so boring if you lose the content, no one understands. It’s absolutely alienating, terrible.

MH: Were you working in a different way than Nekes and Dore O.?

BH: Yes, of course, we were more radical formally and intellectually. And this leads one very easily into a very extreme position. And then we didn’t feel comfortable any more. Then we discovered the image, reality, which we hadn’t done before. We hadn’t been shooting material ourselves because we always took material. Found footage, photographs, anything that was already there. But never shooting real life ourselves. Then we stopped making films and began a performance in 1978—we left the art circles in order to perform. We travelled around the country in a car and performed in German pubs, and later we did this 1979 tour in US museums: Carnegie Institute, Albright Knox (laughs). There were many screens with films and slides and we performed in front. We took images from the trivial cinema, from Hollywood and changed them. We found these big paper dolls of Superman and Wonder Woman and made them move like puppets. We had them masturbate. This performance was very much getting into life after ten years of structural film. Can you understand it, can you imagine it?

MH: So you performed a series of actions that responded to the images behind you?

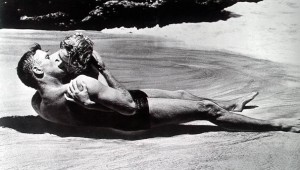

BH: For example one piece began with the trailer for From Here to Eternity. We found it in 35mm and reduced it to 16mm. Then we showed a discarded TV clip about Vietnam which shows soldiers taking bodies out of the water and cleaning their clothes. Afterwards I cleaned a helmet onstage. In the same show we were dealing with Mickey Mouse and Superman, and Wonder Woman and Frankenstein, going from one emotion to another.

MH: In this performance is there anything left of structural film?

BH: No, this was after structural film.

MH: But you’d been working in film all this time, was this a complete break for you?

BH: No, the problem of image and reality was one problem of the structural film, but this worked physically, not in such a didactic way. The whole show was based on illusion—how does it work in an image—and what is reality in the mind. As I step in front of the screen dressed as the Frankenstein monster am I more real than the monster constructed on the screen? Of course it meant more, that we are all monsters (laughs). It was a very emotional performance. But our so-called structural films, for instance, Portraits, were very personal, but only a few people understood that. We felt very alienated from the audience because they couldn’t understand the imagery we were using for structural film, personal imagery in a formal context. Therefore it was necessary to change the work because what we wanted was to communicate, we had to find another way to get to the audience.

MH: Was the audience not so important before?

BH: It was always important. The point was always communication, when we found we had the wrong audiences in the art world this was very disturbing. When people began to correspond with us, art world people, we didn’t appreciate this, this wasn’t the audience we wanted. So we went to the pubs.

MH: How did people react to the performance?

BH: We told the bartender that at one point in the show the light has to be completely dark otherwise it won’t work. If they turn off the light you know you’re successful (laughs). But we couldn’t go on forever, nobody would promote us, we had to everything ourselves and after awhile we didn’t like it any more. It ended when we had a grant to live one year in New York and made Love Stinks. We got the grant for the performance but as soon as we saw the life there the performance wasn’t enough for us. Because life was stronger. Slowly, slowly we started getting that into film. There was no script, after a long time of sitting we started shooting, shooting, shooting. In the end we would up with a big heap of material. The film was really constructed afterwards, it was a completely artificial construct.

MH: What is the film interested in showing or expressing?

BH: Alienation in a relationship and sex.

MH: How does the sex fit in?

BH: The biggest problem in alienation is sex.

MH: Why is that?

BH: It seems I have forgotten what this film is about (laughs). It’s about a love that doesn’t work or is endangered. First questioning of sexual relationships. I would this film every time in a different light. The value of this film is that it’s really dealing with real life and real problems and the courage to deal with it, so it’s a constructed documentary but at the same time it’s real. This was the impact of the film when we showed it in Germany, they were seeing fiction that was absolutely real, real fucking, at the same time they understood the construction. There are very few films that have this power.

MH: Can you describe the film?

BH: I don’t feel like it. Why?

MH: For people who haven’t seen it.

BH: It doesn’t help. You can’t describe films, it’s better to talk in abstract terms because the images are what is most important and this is something you can’t describe.

MH: But wouldn’t you say that, using the ‘Film as Film’ exhibition as a line, one of the big changes is your relation to the word.

BH: But Love Stinks is without words. There’s one text of a priest, a few radio texts, but no dialogue, only music. It’s completely non-verbal film. With Forbidden Pictures it’s different because Wilhelm is telling his dreams. But there’s no synchronous sound in any of the films.

MH: Forbidden Pictures seems like a science film, asking different people to enact the forbidden in their lives. It shows a series of transgressions, centering on the figure of a man who always returns alone to his apartment to listen to the radio. His surround is episodic, these intervening and dramatized moments of transgression, but he seems quite passive, images alternately horrible and fascinating pass through him but it’s difficult to say how it changes him. He seems like the audience.

BH: This comes out of Wilhelm’s life, getting into his personality. the black and white images were a reconstruction of his past—the film was mainly about Wilhelm losing his voice. After we separated I saw this film again in Toronto and I was struck by the truth of everything in it. It was incredible, the film really depicted a situation that intuition handled to become true, it was so strange.

MH: But it’s not a straight autobiography.

BH: I wrote the script about Wilhelm, stories about the family and situations. It’s one part of one person’s head. It’s a psycho-gram.

MH: What happens to a childhood experience when it’s remade in film?

BH: Of course you always construct an abstract situation. They’re separate. It can never be the same image but it can approach the feeling which is the important thing.

MH: But doesn’t it change your relation to your own history?

BH: No. This is another construct. These images transport real feelings even though they’re constructed and this is most extraordinary and I would call this art. This is very important. As it is not precisely linked to historical events it comes very close to the feeling now. What these images really transported is a present. It’s not like taking family photos and looking into my past. The film speaks now, of now. And now I’m working on a project which tries for a deeper connection. I want to connect mythical ideas to today, like how did people think about women, 10,000 years ago and today. Forbidden Pictures isn’t connected with history, it reveals it, and this is how images are constructed. In Freud’s Totem and Taboo, he really believes this must have been a real event: the killing of the father, castration, sleeping with the mother. For me this is a psychological position—you have experiences in your life which never happened. Images of the psyche come from history.

MH: But in your Kali Film you’re very careful to illustrate Freudian ideas about penis envy by arranging pieces of B-films to show that the empowerment of women is linked with the gaining of the phallus. Over and over we watch women with these enormous knives. And it closes with the death of the father who is castrated. This is all very literal.

BH: That’s what’s interesting in these trash films—the horror and prison films—they’re not reality. These films deal with dreams and somehow they are true in a psychic way. If women can act like this in a film, it means society also believes they can do that.

MH: But Kali Film is drawn from films made by men for men. They make a spectacle of women, tits hanging out everywhere, catfights, not an image of empowerment but the reverse.

BH: They’re killing, knifing, shooting because there’s a deep fear that these nice women might do this. If you don’t control them, they kill you. This is like banning the danger—if you ban it, it’s there.

MH: The B-movie women in Kali Film appear as images, rephotographed and lifted out of a world of pictures, constructed not as women, but as types.

BH: I don’t know, I like it. I found that interesting and revealing and I took it from so many films, tiny pieces. I like that image and the feeling about. I can’t discuss this in a controversial way because it’s so simple. Even if these films are made by men, I don’t see the world as so separated, men’s thinking is influenced by women and the other way around. It’s difficult for me to make this division because of the education. It was always different between upper and lower classes. Upper class women always had the same rights as men. Since the nineteenth century women’s rights have gone through all classes. But women were never completely subordinate, only a small class of women.

MH: Is your film part of that struggle?

BH: This film is dealing with deeper images that have always existed, in archetypal forms. Now, in the present time, as women become more threatening, more films show threatening women, you can see it from the statistics. Kali Film is also a kind of statistic about this rising fright, but it’s ancient at the same time.

MH: If the Forbidden Pictures is Wilhelm’s is the Kali Film yours?

BH: No, the next one I’m making is mine. The women’s film was supposed to be one part of the new film, then all these other movements developed and it became its own film.

MH: Can you talk about the difference in audience response between Forbidden Pictures and Kali Film—the man’s film and the women’s?

BH: Not really. Forbidden Pictures is much deeper, Kali Film is much broader. The next film goes into deeper spheres.

Birgit Hein Filmography

(all films made with Wilhelm Hein)

1967 S&W (10 minutes); Und Sie? (10 minutes)

1968 Rohfilm (20 minutes); Grun (24 minutes); Bamberg (15 minutes); Reproductions (28 minutes)

1969 625 (34 minutes); Work in Progress, Teil A (37 minutes)

1970 Work in Progress, Teil B (8minutes); Auszuge aus einer Biographie (6 minutes); Madison/Wis (10 minutes)

1970-72 Portraits 1 (50 minutes); Replay (22 minutes); Fotofilm (10 minutes)

1971 Work in Progress, Teil C (23 minutes); Work in Progress, Teil D (20 minutes); Doppelprojektion I-V (50 minutes); Zoom lange Fassung (21 minutes); Zoom kurze Fassung (9 minutes)

1972 Liebesgrusse (8 minutes); Yes to Europe (15 minutes); Aufblenden/Abblenden (24 minutes); Doppelprojektion Vi + Vii (25 minutes); Scharf/Unscharf (6 minutes); Dokumentation (25 minutes); Fussball (60 minutes)

1973 Ausdatiertes Material (50 minutes); God Bless America (3 minutes); Stills (75 minutes); London (30 minutes)

1974 Structural Studies (37 minutes)

1975 Deppelprojektion Viii-Xiii (25 minutes); Portraits II (24 minutes)

1976 Materialfilme I (45 minutes 1-3 screens); Materialfilme II (35 minutes 35 mm)

1971-77 Home Movies I-XXVI (30 minutes)

1978-79 Verdammt in Alle Ewigkeit (60 minutes); Das Konzert (50 minutes)

1982 Love Stinks (82 minutes)

1986 Forbidden Pictures (90 minutes)

1988 Kali Film (70 minutes)

(Originally published in The Independent Eye Vol. 11 No. 2/3 Spring 1990)

More information about Birgit Hein can be found on her fab website at: www.hbk-bs.de/bhein