Chris Gallagher: Terminal City (an interview) (1994)

The fringe has always counted among its membership a group of soft scientists who wield their cameras like computers, examining the machines of reproduction and the new worlds these machines make possible. Chris Gallagher is one of their number, coolly offering reflections of ourselves in the mirror of technology. Gallagher is part of the first generation of the Canadian fringe who learned their chops in film school. Here, fringe film was served up as a course option, with survey histories founded on an American model of lyrical poetics. Without the possibility of earning enough income from an artist’s manufacture, many fringe makers have returned to Canada’s post-secondary school system, taking advantage of in-house facilities and secure revenue. Gallagher has joined their ranks, teaching at the University of Regina before finding permanent employment at the University of British Columbia. But his tenure has not been a simple one. Plagued by rising unemployment and ballooning provincial deficits, ministries of education across the country have demanded a job oriented curriculum. Inside Canada’s film schools this has meant a renewed emphasis on technical training in the hopes that skilled craftspeople will find employment in an American film industry lured north with the promise of cheaper productions and a skilled labour pool. The commercial climate that pervades Vancouver is fuelled by a colonial press consumed with an American manufacture. All this has done much to found a conservative climate in the educational settings of the West Coast, in which the relevance of the fringe is increasingly suspect. For his part, after spending four years on the feature-length Undivided Attention, Gallagher seems to have completed a cycle of his own. Turning away from his own interests in the avant-garde, he completed a feature-length drama entitled Where is Memory? His most conventional film to date, it relates the story of a man whose sudden amnesia impels him to return to Germany to restore memories of the Second World War. That the fringe should be forgone in favour of an absent memory is an apt enough metaphor for its ongoing struggles to restore relevance to its idiosyncratic eruptions. That it should pale in the face of a world at war underscores the necessity of its political engagement in a climate ever more attuned to pacifying media spectacles. Renegotiating the links between marginal culture and mainstream practice has long been an imperative in the explosive sideshows of filmers like Chris Gallagher.

CG: I began painting in high school and went on to study fine arts at the University of British Columbia. I continued painting, made sculptures and mixed media, and was introduced to experimental films. It seemed to me that you could speak more clearly to an audience without the pretext of a story. Stories kept people interested so you could slip in a message; experimental films were more direct. The first film I made was called Sideshow (4 min b/w 1972). It opens with a man dressed in a loud sports jacket walking onstage, opening his briefcase and taking out a baby. Grinning, he sits the child on his lap and puts his hands in the baby’s back, as if the child is a puppet and he’s pulling the strings. Then he puts the baby away in the suitcase. After he sits back down a stagehand comes out, rigs a harness on him, and he’s lifted up to the rafters to wait for the next show. There are strings attached to each performance and the film unravels these in a potentially infinite series.

I graduated in 1973 hoping to work in film, so I applied to the Canada Council for a grant and received $2,500, which was all the money in the world then. That’s when I started working on Plastic Surgery (19 min 1976). I saw it as a dialogue between two worlds: nature and technology. I gathered images of rocks, trees, and water and pitted them against images of high technology, especially the space program. Life in space depends on science, and I tried to match the movements of the astronauts with natural movements, cutting between a whale’s swimming and an astronaut’s space walk. The similarities are striking. There was a lot of optical printing using mattes and superimpositions to layer the images. I’d recently broken my ankle and the doctors held it together with two screws, eventually removing the screws and sewing me up. I shot the operation in super-8 and it’s a marvellous image, this screwdriver poking into my ankle. As soon as you cut into the skin it becomes a mushy, undefined mass, whereas technology is always so clean and precise. Although the operation looks unpleasant, it’s really an image of these two different processes working in harmony. There’s an obvious relation between the surgery and film editing; both doctor and filmmaker are plastic surgeons. Apart from “doctoring” the image, filmmakers assemble their work like Dr. Frankenstein — they go out to a graveyard to gather pieces, then stitch them together and give them life through lightning. A film is such an impure thing, it forces together all these elements which are lit up in the end, staggering across the screen.

MH: The way natural elements are replaced and transformed by technology seems emblematized by images of David Bowie and Evil Knievel, two showmen who have created their personas through the media. The film’s landscapes are transformed via video synthesis into mediascapes. This movement of separation and replacement grows until the atom bomb explodes, signaling a final separation of the planet and its inhabitants.

CG: I think every film had an atom bomb in it then. Much of our public Imaginary is obsessed with violence, pictures of death, which don’t seem to be able to prepare us for our own end. Why is the mainstream filled with death? They’re fantasies of control. I think people share a dream of killing others, of taking charge of death. An early placard advertising the new invention of cinema claimed that with the advent of portable equipment, colour, and sound, home movies would ensure that death would no longer be final. Why would people be more fascinated watching death than sex? I think they’re part of the same axis, at least in the male media world. The more sex is denied the more killing we see. They form an alternating current.

MH: In Plastic Surgery you used other people’s images without crediting them — the image of the bomb, for example, or the astronauts. How would you feel about someone using your images?

CG: You don’t make an image, you put a lens in front of a scene. There’re images all around us right now, but we don’t have the camera to “take” them. Making images is never a private act, they’re free to be taken up by anyone else and re-ordered. I feel the same about people walking through public space. It’s all public domain — being visible implies consent.

MH: Image theft, or appropriation, has a long pedigree in art, but is much more prevalent here in Vancouver than in a place like Toronto.

CG: There’s a difference between the two cities. In Vancouver I’m surrounded by mountains and ocean, whereas Toronto is more human-made, its beauty is more intellectual and interior. Here we walk along the beach and find things, or you pick through a reel of old movies.

MH: Your work after Plastic Surgery was much cooler, more restrained and observational.

CG: Plastic Surgery was a big, enjoyable mess, but it was difficult to pin down, and in reaction I wanted to make more empirical, almost scientific work. The first of these films was made in the same year and called Atmosphere (9 min b/w 1976). I got the idea from seeing a weather vane moving back and forth, changing with the direction of the wind. I thought it would be interesting to mount a camera up there. I loved the idea of taking myself out of the picture and letting the elements take over. I built myself a weather vane out of old bicycle parts, steel rods, and fiberglass. Strong enough to hold the camera. It was strangely beautiful. After the wing was built I started looking for locations. Originally, I wanted a pure horizon of water and air, but that was too difficult to find out here, so I set up on Hornby Island instead. The ocean fills the bottom half of the frame, with mountains in the distance and islands on the extreme left and right of the pan. I just set it up and let the wind direct its motion. I shot it three times. Like the three bears and the porridge, the first was too calm, the second too windy, and the third was just right.

MH: Does the wind really change direction that quickly, shifting back and forth?

CG: Yes, which is odd, because the actual point on the island is quite isolated. The trees are swept back, so the wind prevails from one angle, but it gusts and turns. The camera was on a telephoto setting to exaggerate movement, but it does manage to sweep through 180 degrees. At one point, I thought it would actually turn right around.

MH: Would that have been all right?

CG: It wasn’t my intention but that would have been okay. I remember standing behind it thinking what should I do: hide or just stand here? [laughs] I just set it up, hit the trigger and waited for the film to run out. I wanted to give an explanation of how the images had been made, so at the end I show a photograph of the contraption. The wing is responsible for the images, but it’s only revealed at the end, so it causes the viewer to review the film from this new vantage.

MH: Why didn’t you shoot in colour?

CG: Black and white is part of the film’s economy, it’s part of the process of distilling the necessary elements to make the film work.

MH: There’s a sub-genre of folks like Chris Welsby who have set out into the landscape attaching the camera to things, allowing us to watch the natural world in a different way — from its own point of view.

CG: I didn’t see that work until this year. He’s attached cameras to the boughs of trees and windmills. I think Atmosphere’s sound and rhythm make it more than a science experiment. I started with an appropriated drum track which I cut into small loops and recomposed. The track is very manipulated and staccato and percussive, whereas the shooting is continuous. The track is composed of small manipulated segments, so it’s the opposite of the image, but the two come together nicely. I became interested in the 400-foot roll as a self-enclosed unit. Ten minutes is a wonderful length; it’s like a little lesson. If you assumed a ten-minute length for your work, and tried to be so rigorous you didn’t need editing, filmmaking could become a practice of attention. I thought of releasing a whole series of 400-foot films and ended up making just four — Atmosphere, The Nine O’Clock Gun, Terminal City, and Seeing in the Rain.

MH: Why the four-year gap between Atmosphere and your next film, The Nine O’Clock Gun (10 min 1980)?

CG: Is there? It must have been because of my photography and performance art, but I should have kept making films. I don’t know what made me start again. I remember experiencing [Vancouver’s daily] Nine O’Clock Gun as a growing expectation that climbed to the point of its firing and then subsided, beginning the day-long wait for the next blast. Its cyclical nature recalled film’s relation to cycles of repetition and ritual. The best way to represent it was to film in real time the audience in the theatre waiting alongside the audience at the gun itself; for both, the gun’s firing comes as a surprise. While the firing’s inevitable, like a film’s climax, there’s no foreplay, no indication of just when it will happen. There’s something ambiguous about the gun because it’s housed in a metal box, so it looks more like a tin shack than a gun. You wouldn’t know there’s a gun there apart from the title. On the soundtrack you hear kids sitting on the same hill the camera’s resting on, asking questions like, “What time is it? When is it going off? This is boring.” There’s an everyday sense about the film which is interrupted by the very short firing of the gun and its aftermath. This narrative of waiting reduces the entire action to a single moment. Among the film’s 12,000 frames it boils down to just one. The bang comes in the middle of the film, lending equal weight to the anticipation and the effect. In the end, like in Atmosphere, there’s a little coda which features nine repetitions of the event, seven in real time and two slowed down. The last frame of the film freezes the red fire coming from the cannon’s mouth — the frame that’s given shape to the movements of the people around the gun.

MH: The woman who has come to sit with her two children raises her arms in a gesture of surprise, but viewed in this series of repetitions her movements seem worshipful, her arms raised in praise and exultation. The waiting and repetition draw attention to the transcendental impulses that underscore our everyday activities.

CG: The firing’s an event peculiar to Vancouver, and I liked the idea of making a work that would export this local practice. The first films made in Canada were made in that spirit — travelogues showing off waterways, fertile farmland, and local curiosities.

MH: A year later you finished another 400-foot film, Seeing in the Rain (10 min 1981).

CG: I was interested in taking a scene where one small element of perception was changed, and seeing what followed. Seeing in the Rain is photographed out the front window of a bus running down Granville Street, Vancouver, in the rain. The windshield wiper runs back and forth across the frame, and I synced the sounds of a metronome with each pass of the wiper. I simply recorded ten minutes of this trip in real time, turned the camera on and waited until the film ran out. This ten-minute strip was cut into pieces according to whether the wiper was on the left or right side. If the wiper is on the left I cut to another shot where the wiper is on the left, so the wiper looks continuous, but the view outside the window changes. Any notion of continuous time is shattered. The bus moves from A to B, but not directly. At one point in the trip, the bus I’m in follows another bus which has a sign on its back, “What’s stopping you?” But while the bus makes many stops, none of them are final. It’s a hint that time doesn’t have a beginning or an end. Like much of my work, the main character is time. The sound of the wipers suggests a clock working, and their apparent continuity in the face of the disjunctive trip creates a bewildering paradox; the time of the film is correct but the film’s space is upset. Cinema’s a beautiful place to work out theories of time because time is one of its plastic elements. Cinema can serve as a model for different notions of time. Someone should open a department of time, a study of time through its representation in photography and film.

MH: Tell me about Terminal City (10 min 1981).

CG: I wanted to keep things extremely simple, get the best view I could and let the camera run. I set it up in front of the Devonshire Hotel, which had been readied for demolition. With all the glass taken out of its windows, it appeared like a death mask with its eyes burnt out and blackened. When the gunpowder’s released, the building collapses in extreme slow motion, its destruction obscured by the rising smoke. I used another ten-minute take, figuring how much I’d need to get a preamble, the explosion, and then its aftermath. A camera is just a projector turned inside out, and both generally run at twenty-four frames per second. But some actions are only visible at forty fps, or eighty, or one hundred and twenty. Recording in “real” time sometimes obscures an event instead of revealing it. While editing, filmmakers grow used to looking at the world very quickly and very slowly, and it’s uncanny the way slowing down gestures of a crowd scene, or familial gestures in home movies, uncovers the relations between people. Often their gestures speak in spite of their words, and in a lot of experimental films or home movies there’re no words to rely on. So you learn to follow something else, to direct your attention in a different way. The Devonshire was a classic old hotel which was being destroyed to make way for a new office tower. What was unusual was that they weren’t simply going to dismantle it, but to use an implosion technique. There were other filmmakers making a documentary about the hotel, interviewing the waitresses and the patrons before showing the building collapse. But while we photographed the same event, our work is completely different. The grand old bar and its guests were significant to the other film, but mine was more metaphoric. The smoke looks like ghosts leaving the building. This is underlined by the soundtrack which, like the image, was slowed down. I recorded onlookers whistling and hollering; once slowed it took on a strange, ethereal quality, like a wailing banshee. It was like the spirits of the hotel being released, finally freed. Vancouver used to be called Terminal City because it was on the end of the CPR rail line. The film foreshadows the end of our cities and civilization; it has an apocalyptic feeling.

MH: Tell me about Mirage (7 min 1983).

CG: I went to Hawaii in 1977 and shot travel footage as well as the Kodak Hula Show. Here’s an instance where Kodak provided not only the film and cameras, but also the subject. While tourists wait in the grandstands, hula girls dance and men climb trees for coconuts. This show had been running for fifty years already, so I shot it as a kind of document without a film in mind, and it stayed on the shelf like a good wine before I came across related footage that suggested a film. I bought a three-minute roll of super-8 film entitled The Naughty Wahine, “wahine” being Hawaiian for “women.” It was a roll of soft-core porn, a classic example of objectification at work. While there was much more to it, I used just the initial sequence where she takes off her skirt, gets up off one knee and dances. I made a loop of it, then looped Elvis singing “Dreams come true in Blue Hawaii” for the soundtrack. The naughty wahine and Elvis run throughout the film. The repetition shows the way our culture continually repeats the same messages, until we can’t even hear them any more. They become subliminal. When I found the porn I hoped it would be a sequence in the film. But as a loop, as a central metaphor, it worked better. This became the film’s A roll. Then I cut together a B roll which would show through the body of the women. These were later joined on an optical printer, so both rolls appear at once. The B roll begins with romantic natural scenes — colourful fish swimming in water, palm trees and surf. With the naked virgin on the beach, it’s quite Gauguin-like. I’d come across a reel of home movies made years ago, very innocent stuff of men surfing. These surfers are followed by the Kodak dancers, more trees, and then we see bombers beginning to take off from aircraft carriers, flying through the air and dropping their loads on Pearl Harbor. Then a lava flow interrupts, a natural disaster following a human one, and finally someone opens the doors to a balcony and looks on and the film ends. The juxtaposition is a simple one: you don’t think of Pearl Harbor happening in paradise, let alone the earth’s turmoil. And while this woman is presented as an object of desire, she’s stuck in a series of stylized movements, just like the Kodak dancers. She’s just there on display, and like the Kodak show, she has to do more with the parts of the world the tourists are from than Hawaii. Meanwhile the male’s voice drones on about dreams coming true as things are getting worse, until this guy wakes up and opens up the door to find out what the hell is going on. The mirage of the film’s title is that paradise could exist on earth.

MH: Doesn’t the objectification of the original porn loop continue in your film? She’s naked throughout, her body serves as the projection screen on which all of the other fantasies are shown.

CG: The repetition works against prurient interest. At first it’s eye-catching and voyeuristic, but after a while this feeling fades — repetition exhausts the image. It’s the same with Elvis’s voice — by the end of the film you don’t hear the words any more, it’s just another rhythm.

MH: Your work from Atmosphere to Mirage has been described as structural, narratives of attention where the film’s shape is clear from the outset. Do you think that kind of work has reached its limit?

CG: Audiences aren’t interested any more. But one could still do valid investigations into the material qualities of film. Just because we spent a decade where a few people made some work doesn’t mean it’s finished. For myself it’s over, I’d like to make different kinds of films. I don’t want to become a researcher working in a specialty area. And I don’t want to make the same film for the rest of my life. I was interested in that field because of its simplicity and economy. But after a while I had so many short-film ideas I just couldn’t see cranking out one after another. I want to make feature length works now because I can’t deal with complex issues in ten minutes, and because shorts offer little recognition, they’re difficult to distribute, and they’re invariably shown in the context of other’s work. After Mirage, from 1983–87, I worked on a feature-length film that was constructed in episodes, like a series of short films tied together in a road movie format. That became Undivided Attention (107 min 1987). The opening shot shows a dark tunnel which a train passes into. This darkness is the film itself, from which we emerge at the end of the film.

MH: Undivided Attention contains references to nearly all of your previous work. You show a building being destroyed, obviously recalling Terminal City. But instead of dynamite, wrecking balls and workers are taking it apart layer by layer in time lapse. They work with such care it looks as if you’ve photographed a building’s construction in reverse.

CG: The sound is from an old film describing the attack on Pearl Harbor. The building looks like a war ruin, and if you were a Pearl Harbor survivor it might carry this association. It’s like a moment of time slipping through a crack and ending up in the wrong place, or the way small events in our lives trigger seemingly unrelated associations. I appear in this scene looking into the camera from fairly close up. I wanted to create a tension between background and foreground. The audience can see what’s happening but I can’t. I watched it for the first time on film, just like the audience, so even though I was there I didn’t see any more than they did. The next scene shows a traffic cop standing in the middle of the road. He’s there as a sign of logical order, but the cars are moving past in all directions so his gestures seem futile. A number of questions taken from a personality test play on the soundtrack. The cop’s work-related isolation is reflected in the discipline of psychology, which begins with the premise of an “individual”’s uniqueness and isolation. Both models are used to organize experience, only it doesn’t seem to be working. The next scene brings us to a demolition derby where everything is out of control. There’s no sign of a cop here and the rules are simple: destroy the other cars without stopping yourself. The last car still running wins. It’s all set in a dirt pit like a rodeo, and a dozen cars bash away like gladiators. In many ways it’s a perfect model for everyday life — everyone for him/herself, smashing headlong into others. Because it’s filmed in real time without any camera movement, the wrecked cars accumulate in the frame like bits of a composition. The camera looks down at the policeman and the demolition derby, and then begins a movement upwards, attached to a car driving into the mountains. Then the camera comes off the car and follows the flight of snowflakes, mimicking them. After the falling snowflakes, we see a snow shovel at work. The camera was attached to the shovel by drilling through the handle and putting a bolt through it into the bottom of the camera. The shovel can be operated quite normally, and while shooting, the shovel is always centred in the frame because it’s attached to the camera. While I’m shovelling the walk, the snow appears to defy gravity because it looks like it’s flying off the shovel into the sky. That’s because the shovel is always right side up, with the camera, while the background turns upside down. It’s like the perceptual puzzle of looking down the railroad tracks and watching them disappear in the distance. The fact is that they don’t draw closer together at all, so do you believe your eyes or your understanding? Undivided Attention plays out this question in a number of scenes, trying to unlearn some of the “facts” of our vision so that we can learn to see in another way. I was thinking of attaching the camera to objects in different categories — at home, at work, at play. I thought of attaching the camera to a tennis racket or a baseball bat, or a lawn mower.

MH: The National Film Board should hire you for a year to travel around the country attaching your camera to different objects and demonstrating their point of view.

CG: The notion of artists at work appealed, so the next scene showed painting, then a writer, an analysis of vision, and then a horn player. There’s a continuity of expression which begins with the painting scene. I attached each of three brushes, one at a time, to the camera and made three separate paintings in red, green, and blue, the three primary colours of film. The camera itself almost dips into each paint can and moves across the canvas, leaving a visible mark as it moves across the white backdrop. The paintings literally become evidence of someone’s seeing, because the path of the camera and the brush are the same.

MH: Later we see an image of a cloth clown blowing in the wind, with interruptive glimpses of fire and neon signs. On the soundtrack, two boys attempt to recount a story which becomes impossibly muddled.

CG: They started telling me the story of the movie they’d seen and it was so interesting I got my tape recorder and asked them to tell me again. Their rendition was as wonderfully confused the second time as the first! They remember elements and impressions which don’t follow in any kind of narrative order, so it really became their own story, not someone else’s.

MH: Norman McLaren said movies never bored him because when the plot died he would watch the scratches. In their retelling the kids are remaking the movie they saw into a film that resembles Undivided Attention more than it does the Hollywood treasure film they watched. Once again, Undivided Attention’s decentred scenes ask us to remember this childhood state, to suspend not our beliefs but our disbeliefs.

CG: The last scenes of the film all feature couples. For the first of these scenes, I built a little scaffolding and laid a heavy piece of glass on top, about seven feet high, with the camera pointing straight up from the ground. People offscreen threw dishes up in a wide arc that smashed on top of the glass. The voice-over features fragments from daytime soap operas, very clichéd situations in which men and women are arguing. Glass is a magic substance because it allows us to see through it while stopping the objects that are moving towards us, so it’s opaque and transparent at the same time. After the dish breaking, we turn to a couple speaking in sync in a room. While she flips through a Vogue magazine, he lies in front of her on the floor surfing TV channels with a remote. The movie he settles on is King Kong. The camera is mounted between them on a device that allows it to make a continuous 360-degree tilt, so it can show her sitting, him lying or the upside-down television set. The paradox of the scene is that while everything is set into motion by the camera’s tilt, nothing is really changing between the two of them. They’re frozen.

All of the couples in Undivided Attention and many of its surrounding scenes are caught in unchanging circles, as if our attentions or desires naturally took a circular shape. And often these circles don’t overlap, they’re stuck inside their own orbits, their own habits. The next dramatic scene takes up this circularity. It begins with a woman reading a postcard sent by a man who is on his way to meet her. The postcard is also a picture disk, a record. He writes, “I don’t understand the words but I like it just the same.” So she puts it on the record player. The camera was placed directly above the turntable and follows the movement of the turntable by means of a crank I built out of a bicycle wheel, so it seems as if the room moves while the postcard/record lies still. It’s as if the record is the real thing, and everything else is “listening” to it. As she moves to the couch the camera follows her, eventually drawing in to a close-up of her eye, which continues to spin like the rest of the room. This is intercut with a scene of the man cycling to see her. I took the door off my car, laid the camera on the floor, and set the bike on the curb, so the bike’s wheel and the camera were on the same level. I had a two-by-four sticking out of the car which was tied to the bike seat, so we moved at the same speed. As the bike moves the camera spins, so it seems again as if the world is rotating around the wheel instead of the wheel turning. I used the bicycle and turntable as vantage points that underline this circular motif. I think what’s implied is that these two are already locked into their own circles, their own habits of understanding which will make it impossible for them to speak to one another. This scene shifts to a drive-in where they watch a film called Valley Girls. One of these girls in the movie decides to break off her relationship. The guy responds by trying to cover up his emotions, saying, “I don’t need you anyways. You’ll be sorry.” They’re caught in the same dumb clichés the previous couple were. This movement of separation prepares us for the final scene, which again is set in two parts. There’s a man dressed in quasi-military garb, as if the war’s over and he’s looking for scraps. He comes upon a pile of books and tries to put them to use by burning them and warming himself, or eating them, or using them as a bed and blanket. This is intercut with a photographer trying to take an image of a nude model. It was filmed off the back of an eightby- ten camera so she appears upside down. We see him constantly adjusting her pose and the camera, but he never finds what he’s after because it doesn’t exist. The act of photographing already distances him from the kind of sensual experience he’s really after. His response to sensuality is to try to contain it, like the guy in the King Kong scene. The music is very grand, almost like an anthem. The entire film is framed by shots that show a train enter a tunnel in the film’s beginning and emerge from the tunnel at the film’s end. It reminds us of the first film of the Lumières, so the film’s suggestion to turn back to childhood also brings us back to the childhood of film. Having chased the light at the end of the tunnel, we’re left to our resources, back in the real world outside the tunnel. The film is finished.

MH: What was your shooting ratio?

CG: Four to one.

MH: Where is Memory? (93 min 1992) was a kind of departure for you, moving away from your more strictly experimental work. Can you tell me how the project began?

CG: Both my parents were in the forces in World War II. My father was in the Winnipeg Rifles and my mother worked as a radio operator in the Royal Air Force. My parents met and married during the war and came to Canada in 1946. As kids we would watch TV documentaries and play war games; some kids had to be the Germans and agree to fall down when they got shot. I wanted to make a film on WWII, but it seemed that the subject was almost exhausted from the Allied perspective. Then I came across a magazine called After the Battle, which offers then-and-now stories and photos on the war. To see the actual sites where these historic events happened was powerful for me because North Americans were not touched in the same way Europe was. I began to wonder how a German veteran might remember the war — it must be very difficult and paradoxical. I developed this idea of a German with amnesia (regarding the war and the Third Reich only) who returns to former war sites to see what he can find. The sleepwalker is like a visitor from the future who tries to return to the WWII era, 1939–45, but misses it by about fifty years. Instead, he lands in the present and tries to discover things about the Nazi period retroactively. Since we can’t go back in time, perhaps we can return to the original space and find traces still there. Historic sites were researched in early 1989 and a crew of six went to Europe in May and June of that year for six weeks of shooting. Some individuals who were interviewed for the film were prearranged but most were discovered during the shooting. I had some idea of what I wanted but all of the action with the sleepwalker was improvised. The film was really shot as a documentary in that I didn’t know what I would find or who we might encounter on the shoot. The film is based on a fictional premise but shot as a documentary. Perhaps it could be called a ficumentary. We rented a van and a car and went from location to location without knowing how long we would stay in one place. This was very exciting although sometimes hard on some of the crew who couldn’t keep up. There were quite a few incidents during the shoot. The main actor (Peter Loeffler) and I were arrested by the Munich police. We were shooting a scene at the Marienplatz in which Peter was dressed in a Nazi uniform. Someone complained and soon a contingent of police arrived and Peter and I were taken to the station. Peter was photographed in the uniform and they threatened to detain us for displaying a Nazi swastika (hakenkreuz). After some fast talking and profuse apologies we were released. This incident scared Peter and the crew, so I had some difficulties getting them to do things after that; for example, the crew refused to go to East Berlin as they were terrified they would be arrested and never get out. From the original idea to its completion took me from 1988 to 1992. The editing took a long time, as I had to develop a structure and a story. The film went through many versions, and it was a very difficult but creatively exciting process. I also had to raise more money to finish the project. The total budget was about $120,000.

MH: How much have your other films cost?

CG: Plastic Surgery cost $3,000 and was paid for by the Canada Council. The Nine O’Clock Gun, Atmosphere, and Seeing in the Rain were about $500 each, 11–12 and Sideshow $200 each. Undivided Attention cost $30,000, $20,000 of which came from the Canada Council. Mirage cost $2,000 and was paid for by the Canada Council.

MH: Do you think we’ve ever had an “avant-garde” film practice in Canada? Is anyone making that work any more? Is it still relevant?

CG: I think we’ve had one, but the emergence of video has taken away much of its impetus and pushed film into a marriage of commercial and independent film. Because avant-garde film can’t find a partner in that marriage, it’s left out. Films have to be more narrative now and I’m not really sure what’s avant-garde any more. It’s been so marginalized. I show my students interesting work and they hate it. It seems that people have lost their curiosity about the world; it’s ceased to become important. As if everything’s already been done.

Chris Gallagher Filmography

Sideshow 4 min b/w 1972

11–12 4 min 1972

Plastic Surgery 19 min 1976

Atmosphere 9 min b/w 1976

The Nine O’Clock Gun 10 min 1980

Seeing in the Rain 10 min 1981

Terminal City 10 min 1982

Mirage 7 min 1983

Undivided Attention 107 min 1987

Where Is Memory? 93 min 1992

Mortal Remains 52 min 2000

Originally published in: Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada, ed. Mike Hoolboom, 2nd edition; Coach House Press, 2001.

Chris Gallagher: Movie Machines (1994)

Chris Gallagher has often been referred to as a ‘filmmaker’s filmmaker’, shedding light on a variety of circumstances which double as metaphors for the act of representation. His watch-and-wait documentaries possess an analytical air, lending an observational cadence to the sometimes furious rhetorical strategies of the fringe. Gallagher’s work in contrast is coolly scientific, offering reflections of ourselves in the distended mirrors of our technology.

Gallagher is part of the first generation of the Canadian fringe who learned their chops in film school. Here, experimental cinema was served up as a course option, with survey histories founded on an American model of lyrical poetics. Without the possibility of earning enough income from an artist’s manufacture, many fringe makers have returned to Canada’s post-secondary school system, taking advantage of its extensive in-house facilities and secure revenue. Gallagher has joined their ranks, teaching at the University of Regina before finding permanent employment in the film program at the University of British Columbia. But this return has not been a simple one. Plagued by rising unemployment and ballooning provincial deficits, ministries of education across the country have demanded a job oriented curriculum. Inside Canada’s film schools this has meant a renewed emphasis on technical training, in the hopes that skilled craftspeople will find employment in an American film industry lured north with the promise of cheaper productions. The commercial climate which pervades Vancouver is fueled by a colonial press consumed with an American manufacture. All this has done much to found a conservative climate in the educational settings of the west coast, in which the relevancy of the fringe is increasingly suspect. For his part, after spending four years on the feature length Undivided Attention, Gallagher seems to have completed a cycle of his own. Turning away from his own interests in the avant-garde, he completed a feature-length drama entitled What is Memory? His most conventionally wrought film to date, it relates the story of a man whose sudden amnesia impels him to return to Germany to restore memories of the Second World War. That the fringe should be forgone in favour of an absent memory is an apt enough metaphor for its ongoing struggles to restore relevance to its idiosyncratic eruptions. That it should pale in the face of a world at war underscores the necessity of its political engagement in a climate ever more attuned to the pacifying media spectacles which dislocates its constituents. Renegotiating the links between marginal culture and mainstream practice has long been an imperative in the explosive sideshows of filmers like Chris Gallagher.

Plastic Surgery (19 min 1976) was Gallagher’s first important foray into the fringe. Its central trope is an ankle operation, glimpsed in hazy close-ups of blood and flesh, in which the filmmaker’s skin is parted to make way for a surgical implant. Interleaved with images of a guillotined emulsion, Gallagher aligns the body of film with the body of its maker. It is an image learned in the assembly line, whose deconstructive practice disassembles our vehicles of conveyance into a linear progression of parts. For Gallagher the workings of our technology proffer an image of ourselves. It is the body which has been broken and restitched, the wholeness of our flesh recast in the image of a machine of parts.

Begun in the body of its maker, Gallagher casts his gaze outwards, imaging the natural world through a synthetic babble of garishly colourized landscapes and single frame pyrotechnics. His re-processed flora and fauna seem the natural outcome of a geography littered by Kodak Photo Spots — those markers stationed by North America’s film giant before the monumental splendors of the natural world. Ensuring “the perfect photograph,” these stations of the cross-hairs ensure a uniform perspective, even as their own handling of emulsion ensures a uniform processing and treatment. It is just these “nature beautiful” subjects to which Gallagher turns his undivided attention. Plastic Surgery foregrounds the phallic perspectives of the machine, which figures nature as a tabula rasa, an emptied or neutral canvas awaiting the inscription of progress. Lifting off from this man-made universe are astronauts, wholly reliant on NASA’s simulated womb. Wrapped in their mummified cocoons, their blank expanse a humanoid screen for the projection of the frontier, these spacemen look out from the leading edge of our manufacture, “going where no man has gone before.” All too soon they will be replaced with more efficient machines of surveillance, as world space programs extend our scopic drive into unmapped space.

In the next four years Gallagher would retreat from the hyperbolic montage of Plastic Surgery, offering up the cool, structuralist studies for which he is best known. Made in the same year as Plastic Surgery, Atmosphere (10 min 1976) is a minimalist plein air portrait. Using a hands-off approach pioneered by arch British structuralist/landscape filmers like Chris Welsby, Gallagher mounts his camera on a fluid head tripod and affixes a large wing. Gazing over the untroubled waters of Hornby Island, the camera executes a number of rapid pans in both directions. If its back and forth movements mime the gesture of reading, its source is a mystery until the filmmaker reveals the apparatus in a photograph which closes the film. It shows the camera braced on its three legged support, with a large sail affixed behind, allowing the camera to turn with the changes of the wind. Atmosphere‘s closed-circuit address elegantly drafts its seemingly impossibly problematic: to see the wind. Gallagher’s camera-sail glimpses the effect of the invisible, guided by the unseen hand of the natural world. This image of a co-operative relation, of an eco-cinema founded on a machine’s submission to a prevailing windscape, stands in marked contrast to the aesthetics of simulation proffered in Plastic Surgery.

Unexposed film stock is offered for sale in standardized lengths of one hundred and four hundred feet. In four of his films, Gallagher followed this restriction – that each be made using a single 400′ (ten minute) length of film. Atmosphere was the first to begin these lookouts, and The Nine O’Clock Gun (10 min 1980) is the second. It simply maintains a single view of a cannon overlooking the city of Vancouver. Like so much of his other work, Gun is marked by a reflective period of waiting, using duration to ‘suspend’ the pace of our usual attentions. The frame demarks an unwavering arena of interest, its unchanging perspective monitoring its surround in a stare that marries cinema-verité with the scientific method. So what happens? People gather on the rise overlooking the bay, snippets of conversation are overheard, the whole unfolding in ‘real’ time. Halfway through the film, and quite without warning, the metal box perched frame right emits a resounding blast. Refusing to cut at the film’s obvious dramatic climax, the action simply endures as those who’ve gathered chat with one another before picking themselves up and moving on. Other passersby stroll past. Finally the screen darkens. Nine repetitions of the firing ensue, the last two in slowed motion. The gun’s discharge is revealed alongside the reaction of its spectators, whose split-second gesticulations elude all but the most careful viewers. Reviewed here in the film’s coda, it reveals a distinctly religious attitude. The woman who has come to sit with her two children raises her arms in a gesture of surprise, but viewed in this series of repetitions her movements seem worshipful, her arms raised in praise and exultation. Even as she assumes an attitude of prayer her progeny reel back from the fearsome blast. Here Gallagher draws attention to the transcendental impulses which underscore our everyday activities. While the bulk of The Nine O’Clock Gun exhibits a cheery banality in its real time record, the blast’s review unveils the hidden patterns of everyday life — implying perhaps that all of the apparently casual and random movements of the film were orchestrated and rehearsed. That all of our gestures could be gathered together and unified by its unseen cause, if only a keen enough attention were employed.

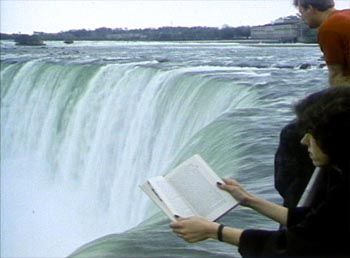

The answering shot to The Nine O’Clock Gun appears in Gallagher’s Terminal City (10 min 1981). Photographed in super-slow-motion, we are witness to a stolid and menacing architecture, a building which looms impassively into the frame, its windows a blackened row of blinds. We wait opposite its four cornered enclosure, imagining the lives that have passed through these walls. All of a sudden the picture changes. While the camera never wavers, its subject begins to collapse, the ties of brick and mortar buckling under an unseen force. The walls tumble inwards, falling in a dust shroud that slowly fills the frame. The soundtrack takes its cue from the image, its recording of the event likewise replayed at slow speed, offering a dirge-like accompaniment to this destruction. Terminal City functions as a kind of elegy for architecture, for all those buildings effaced in the name of urban renewal. Its transformation of the fixed and unchanging into the most temporary of respites, is also a revelation of mortality and the need for mourning. Its unyielding stare stands watch over a cityscape whose restless re-creations are founded on the invisible ruins of history. The qualifying ‘terminal’ of the film’s title evokes a city of death, a necropolis of discarded and forgotten sites. In rendering disposable the architectures of the metropolis, Terminal City suggests that our cityscapes have come to resemble the images that surround them. Our images have become subject to newfound techniques of digital reprocessing, our hitherto guarantors of documentary proof become the sites of manufacture and invention. Our cities are just the same, their orifices and eruptions simply new sites for the celebration of an infinite present, its reshaped surfaces and convertible ideologies cruising the ever changing text of the city, its rollercoaster semiologies taking the place of memory. Even as our images can be changed at will, so has the rest of our world. Our cities are the image of an image, a shifting glut of perspectives that change because they can, because the possibilities of our manufacture find employment irrespective of popular consent. Who ever voted for the telephone, the automobile, the styrofoam cup, atomic weapons or the home computer?

Seeing in the Rain (10 min 1981) is Gallagher’s triumph, a beautifully simple film traversing the city of his birth. Photographed on a single roll of film during Vancouver’s interminable rainfall, Gallagher positions his unmoving camera at the front of a local bus, peering out of its vast windshield into the traffic beyond. The wipers provide a jerky mechanical rhythm, accentuated by machine sounds on the soundtrack. Into this simple figure Gallagher begins to wield his splicer, cross-cutting passages of the same journey in an astonishing demonstration of the plasticity of emulsion. Seeing‘s subject is our experience of time, unraveled here in a disjointed travelogue that shatters our notions of linearity and causality. Even as we draw nearer to the closing of the bus loop, we are moved closer and further from the neighboring traffic, pulled in and out of intersections, driven past bridges only to be made to approach them again. Time has become concretized here, like the hands of a watch fob, it has been rendered in spatial terms, as a place which can be entered and exited. Seeing unveils the cinema as a time machine, whose shifting chronologies might finally reverse mortality, or more perfectly mimic an interuptive consciousness. It suggests that the cinema might stand as an image of a perfect memory, a memory in which every detail is restored with such precision that there exists no appreciable difference between memory and its reliving.

The interposition of humanity into the natural world again informs Gallagher’s next film, Mirage (7 min 1983). Its central figure is a Hawaiian native caught in a cycle of perpetual disrobing, her image rephotographed from a super-8 porn loop and repeated the length of the film. On the soundtrack Elvis Presley croons “Dreams come true in Blue Hawaii”, and this figure is also subject to a numbing and mechanical repetition. Superimposed over the body of the woman is a narrative of a different order. Begun with postcard-like shots of “idyllic nature,” the natural world is soon home to vacationing surfers, and then to a furious Japanese air attack launched to scuttle the U.S. fleet harboured in Hawaii. A cinematic version of the fall, Mirage‘s trajectory moves from Hawaii’s unspoiled wilds to an invasion by war. In Gallagher’s universe the war machine is never far, our technological imperatives simply viewed as war by other means.

Gallagher spent the next four years hard at work on a single film — Undivided Attention (117 min 1987). Featuring a running time just short of two hours, it is longer than all of the rest of his work combined. It appears as an anthology of shorts, a compendium of visual interests, puns and set pieces loosely strung together with the recurring image of a couple driving through Vancouver in a car. Along the way Gallagher reprises most of his previous work — including firing cannons, collapsing buildings, pans over water and re-edited drives through traffic. These roadside attractions narrate aspects of a machine-made consciousness.

His observations are carried on by a neo-scientific camera rhetoric marked by long takes, a single field of attention, situations in place of a narrativized drama, and a space which manages to be both documentary and fiction. This is not a trip obsessed with its destination, but one content to stop at the slightest provocation — lensing the world in a series of vignettes which resemble nothing so much as a newspaper page — a collage of histories, photographs, advertisements, official statements, suppositions and half truths. We are witness to moments of a drama here which could never cohere into stories, like remnants of an overheard conversation, partial and incomplete. If there were any centre left these would be moral tales, without it, they exhibit the tracks of a canny traveler, one who has made a game of his storying, traveling through a postmodern debris with a wry humour.

Many of Undivided Attention‘s scenes are founded on a virtuosic camera display which features a camera tied to a variety of objects — bicycle wheels, record players, snow shovels, typewriters and trombones. Too perfectly miming the actions of the objects which surround us, Gallagher delivers us to an object’s perspective, transforming simple everyday activities like shoveling snow into puzzling perceptual exercises or hilarious sight gags. Attaching the camera to a succession of paint brushes, the camera dives into paint pots before smearing itself over the canvas. Attached to a record player, it spins at the same rate as the turntable, rendering the turning record perfectly still while the room spins crazily around it. While a trombone sounds out a deflated version of Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyrie, the zoom stick is tied to the slide, adding a visual counterpoint to this rendition. By aligning tool and camera, the image unwraps the perspective of the tool, the object, as opposed to its wielder. We witness events from a shovel’s point of view, or a paint brush, or a record. Gestural cinema is usually encoded as ‘subjective’ — its movements identified with the filmmaker or an actor. But in Gallagher’s drama the only players are objects — so he presents us with a host of subjective objects. If their diction is strange perhaps it’s because they’re learning to speak for the first time, or that the ways of their seeing, too long relegated to the periphery of a merely human endeavour, has been obscured by their handlers. While tools have often been held to be the necessary evil between an idea and its realization, Gallagher suggests here that our tools are an image of the world we live in, an image we are learning to inhabit. That we are building a second universe alongside the first, a universe of images which is absorbing its twin, the world before “in the beginning was the word.”