1. I’m Not Against Pornography: an interview with Claudia Schillinger (1990)

Claudia Schillinger is a thirty-one year old filmmaker originally hailing from Bremen. She studied in Bremen’s School of Art and Music with Klaus Telscher for four years before deciding to move to Berlin. She has made four films and two video installations since 1985. Her work is deeply concerned with sex, power and gender relations and has moved from a material film work (film as film) to an issue-oriented politic conveyed in images, not words. This shift reflects in microcosm a general tendency in Germany fringe film work which has moved from largely formal concerns, expressed in an eroticization of the film surface, to an examination of eroticism itself.

MH: You came to Berlin just seven months ago. Is this new city important for your work?

CS: Bremen is really a provincial town. I made film in Bremen for four years, studying with Klaus Telscher and I wanted to extend my boundaries. Very quickly you come to know all there is in Brremen, not a lot happens. (laughs) I’m happy in Berlin because there’s so many no-budget and super-8 filmers. Berlin is very fresh.

MH: Where do you meet these filmers? In bars, the cinema?

CS: Most often at festivals. I knew all these names from Bremen but never met them until I came here: Steff Ulbrich, Michael Brynntrup, Alte Kinder and so on.

MH: Do you think there’s some reason why the no-budget filmmaking scene should happen more in Berlin?

CS: Berlin has underground scenes in music, theatre, films and art.

MH: When I was speaking with Steff Ulbrich, he talked about a super-8 ghetto that existed here in Berlin. He said that a lot of people used to work in super-8, that it was fashionable for a time, but not so much anymore. He has the feeling that if you continue to make super-8 films you can reach only other filmmakers, never a real audience. Do you think that’s true?

CS: No, I don’t think so. In Berlin the people are more open to underground films or super-8 low-budget films. If you do it in little towns in Germany it’s impossible. The atmosphere here s conducive to working. You have more communication about your own films, you meet a lot of people talking about the films you’ve seen and so on.

MH: When people are making work do they reach out and ask others to weigh in with opinions?

CS: I would call Michael Brynntrup perhaps or Steff. When I’m cutting a new film I need people to tell me what it’s about. So it does happen here.

MH: Does that mean there’s not so much a feeling of competition amongst filmmakers? Can you talk amongst each because you’re not fighting over screenings, money or attention?

CS: It’s not a strong competition. It’s an open competition, so it’s possible to talk about the films in spite of this competition.

MH: How did you get interested in making films?

CS: First I studied graphics and I took a lot of photographs looking for my personal outlook/expression. I visited the film class in Bremen just for fun, and ended up staying. Klaus Telscher was teaching. I came to film by accident.

MH: This was in an art school.

CS: Yes. That’s where I started film.

MH: Can you describe them?

CS: They showed different views on women’s sexuality. In the beginning I worked a lot with film materials, particularly the grain.

MH: How did you do that?

CS: Printing from TV, from video to super-8 film, then back to TV, to 16mm, and so on, creating patterns through generations of film. I used to be very interested in these pictures, but today it’s not so important to work with the material. The first film I made showed stills of women’s positions in art and prostitution, mixing them together. The second film was more romantic, it was double-exposed, a black woman and a white woman, always me with black clothes and white clothes. It was about sexuality and identity. The white woman danced whie the other stood still. Their movements would overlap. Sometimes I developed black and white film like Klaus Telscher, by hand, but now I go to the lab.

MH: So this film is a dance film but also like a trance film in a way – like a personal psychodrama, trying to bring together these two parts. Like Maija Lene-Rettig’s L’Appasia.

CS: Or L’Appasia is a bit like this film. My new film between is a concrete attempt to show sexual fantasy and to find special film forms for these fantasies.

MH: Why is it important to find a special form?

CS: You know about pornos – they have a special form. I think it’s not the form I feel. I was looking for moments of passion. For me the film brings together many moments of passion, there is no realistic surrounding.

MH: The film refuses continuity, each experience is isolated and demands that the viewer put them together. Why this interest in the fragment?

CS: Perhaps it’s a bit like a puzzle. You take an ass, and breast and cunt and dildo and you combine them as you want. The fascination for me is not to say here’s female sex and here’s male sex. I want to combine these fragments into new forms.

MH: You mean that sex exists not in one place or the other, but somewhere in between?

CS: Yes, between is the title of the film.

MH: Did you start with an image?

CS: I had an image with breasts and dildo and began to work around it. I started to dance with this dildo and saw that I moved differently. This was the beginning. There are two women in between – one lies in bed and fantasizes, while the other woman stands and brushes her hair, looking in to the camera. They’re in two different places. Between these two women there’s a lot of pictures without heads or legs, pictures with dildos, cunts. Later on the dreamer stands by a tree and masturbates. I intercut pictures of cunts and the dildo. (pause)

MH: Don’t leave our readers in suspense. Tell us how it ends.

CS: In the end she’s sitting on a toilet and you hear the water coming down into the toilet. She leaves singing, and this is the end. But it’s very difficult to describe a film in this way I think. It’s ten minutes long.

MH: One woman appears passive, the other active. While it’s possible to view the film in a number of ways, between seems the fantasy of one woman pictures in various ‘between’ states: on a toilet, sleeping. She’s the figure to which the film returns after the montaged clusters intercede, she makes a centre for the film. Both the way that it’s cut and the way sex is shown is quite aggressive. Do you think that’s right?

CS: For me it’s right but many people tell me it’s not aggressive, it’s a soft picture. I think it’s a kind of sexual feeling to increase the feeling until it’s painful. I wanted to show it.

MH: Is that because there’s no feeling without that pain, or admitting at least the possibility of pain?

CS: No, it has to do with female sexual fantasies. The film is based on painful moments which arrive from womens’ sacrificial attitudes. Using strong images is a way to overturn these attitudes, but also to demonstrate passivity. Women’s sexual fantasies show a lot of sacrificial attitudes. I think it’s a kind of death feeling. For women, it’s forbidden to have sexual feelings so they imagine situations where they are forced into sexuality. It’s not only a feeling of death but a fascination with aggressivity or brutality.

MH: Do you think sex always narrates power?

CS: Yes. For me, sex has two faces, the first in the head (imagination and fantasy), and the other is the real feeling on the skin. This film, between, is more in the direction of the imagination. It tries to find some pictures which are sexually stimulating, which are my pictures. It’s an aim for me to find a form which has two parts: skin feeling and imagination.

MH: When you said earlier that in your previous work you were more interested in working with the material this seems also related to the skin. Do you think there’s been a move from the skin to the head?

CS: Yes. The skin holds the classic female view on sexuality. When you see some films from women on female sexuality there’s often cloth and roses. For me it was interesting to another view, an aggressive view. Because if you stay on this point, with this skin feeling, you cannot come to an active sexuality.

MH: The kinds of films you’re describing are quite symbolic, whereas your film is quite explicitly physical. But there’s a growing group in the German women’s movement who might feel these images are quite pornographic, and that porn is always aimed against women. They insist that its very explicitness makes it degrading.

CS: I’m not against pornography. I think it’s important for women to get a feeling for the speech of sexuality, and also the language of pornography which is a male language. Women ask, “How can I speak sexually, how can I film sexually?” You can’t pass the male expression, you have to go through it. that’s my position. If you go through there are strange moments when you don’t know what you are. are you female or are you too male? But it’s important to go through. It’s a kind of appropriation to use male expressions, a female appropriation that’s important. You have to feel your own aggressiveness, you have to feel it.

MH: There’s a few films that play in theatres around the world. But the kind of films you make play in small houses before small audiences. Because your point is a political one – taking over an area that has long been a male preserve – doesn’t making an experimental film marginalize what you’re trying to do? Doesn’t this reinforce the already marginalized expression of women?

CS: It’s a new female language – not just my film. If you go to commercial cinema and make commercial films you cannot use a new language. You have to make a lot of compromises and that’s not the way, you make a lot of lies.

MH: Is a woman’s cinema always speaking from the margins, the outside?

CS: If you have a new theme or object you must have a new form because they’re together: form and content.

MH: But most wouldn’t agree. Many don’t understand these films and don’t want to go see them because the form makes them unrecognizable.

CS: I don’t care about all the people.

MH: When I was speaking with Steff he said that most of the experimental filmmakers whose work was important in some way had a common theme of sexuality, and that this would be the case for another ten years. Do you think that’s true? (pause) Now you can tell everyone how sexy Berlin is.

CS: Berlin is very sexy. For me sexuality contains all existential problems. They are in sexuality where they take an extreme form, and that’s the point. You understand? Perhaps because there’s a lot of extreme forms of sexuality in Berlin, you find a lot of different perverse people.

MH: Most of whom are also making films. (laughs)

CS: Berlin is the town in Germany where may young people come and try to find new forms of living. The German squatter movement started from Berlin, about 140 houses at the turn of the decade, and all of the squatters wanted to find a new way to live which should be communal, to live together, to sleep together. And this kind of filmmaking is a part of that life. A lot of sexual films function only because sexuality is forbidden. I think my film would not function if people were free in their own sexuality. A lot of people go to cinema to see sexual films, there’s always a big audience. They are always disappointed though.

MH: And how does your film function in that economy?

CS: I don’t know. People are very quiet when it comes on. And in the last scene in the toilet they start to drink again.

MH: Do you think your film could show in a porn theatre? Is that something you’d be interested in trying?

CS: If a porn theatre decides to show this film, okay. In commercial pornos they want to have women behind the cameras, they’re looking for women to make porn films and develop a new market.

MH: Does your film fit into that?

CS: I don’t think so. It’s a little too abstract. In commercial pornos you see a story. I just don’t know whether it would work. I think my film has a lot of distance towards its audience. My film is about fantasy, about the expression of a language which shows my fantasy, and this is the opposite of porno. Porno has no fantasy, it just shows the simple act, and the people who go there don’t have enough fantasy to see it for themselves. So they go to the theatre to see the pure act which has nothing to do with my fantasies. In between you see the dildo and the cunts but always in short cuts, minimal pictures, which is different form a porno. The audience doesn’t need fantasy at all. In my film you can recognize a part of your own fantasies, it’s not showing you in such a direct way that it kills your own.

MH: Are you working on a new film?

CS: Yes, I’m writing a script. It’s about sexual moments in childhood. In Germany there’s two discussions about sexuality. Shall we forbid pornos, we women, and the other discussion is about child abuse. And the moral is the same. I want to try in the new film not to show sexual abuse, but to imagine it as the fantasy of a child.

MH: So instead of staring with an image, you start with an idea, a script and words. Will there be actors?

CS: Yes. I want get money from the Film Burreau in Hamburg perhaps and to work with real actors fro the first time.

MH: How much did between cost?

CS: For only the materials including three prints: $2000. for the rest of my films between $700 and $1500. I never pay actors or myself or the equipment. I own my own editing table. I get the equipment from the art schools in Braunschweig or Bremen.

MH: Will the new film be longer?

CS: Perhaps 30-40 minutes. It will be more like a fiction film.

MH: German experimental cinema from the 1960s and 1970s didn’t tell so many stories. It worked instead with materials like your early films. Many filmers have remarked on the shift away from this period of working, from ‘film as film’ to a time now where stories are increasingly important. Why is this change important for you?

CS: Perhaps it’s not correct to make a distinction between material films and story films. Before they were all personal films. Birgit Hein made a structural film that was a personal film and told a story, Roh Film (1968). Every good structural film tells something about its maker and their view. The point we come from is the same. It’s always a personal interest in film and film form as a subject. I think the script is like a fiction film and later on I’ll work with the printer and make an experimental structure for it. I can get deeper with experimental structures and wider with fiction. After working with the film’s material, its chemical make-up, I became more interested in cutting, and finally this montage broke me loose from the material.

MH: Are you more interested in issues, the social aspect of the film, as opposed to the film itself?

CS: My films were always personal. The first films were more romantic and that’s marked a change in my thinking. What was important was the feeling, the warm feeling. Now it’s more a cool feeling. I think I’ve changed the distance from my own feelings, my own pictures. I also have much more distance to the social pictures that surround me, that are around all of us. I worked a lot to destroy these social pictures, showing the generations of change. I wanted to show what they were made of, making them bigger and bigger until there’s only the grain pulsing. Now I have more distance to these social pictures. I don’t wan to work with them, I want to find new individual picture, to build something instead of taking something away.

Note from Claudia in 2023:

The Arsenal in Berlin asked me about a screening of between (without royalty) in a queer location in London. I agreed on the condition that they publish the following film description. Maybe you want to use it for my film on your website as well? No demand on my part, just a suggestion 🙂

At the end of the 80s, at the age of 30, my film ‘between’ was, in addition to the cinematic-visual liberation from narrative structures, a personal liberation, a kind of integration of male connoted lusts. If the film is increasingly shown again today, I am very pleased, but I would like to express the desire to see the film in a certain context. The discussion about transgender people today is pushed onto the political-media stage with questionable goals, which I don’t want to see supported with my film. I opened myself to the play with gender stereotypes and put sexual fantasizing in the center of my film. The artistic or even childlike play opens up an inner exploration and freedom in dealing with gender roles. I have remained predominantly heterosexual and, as a mother, I am very glad that I was able to ward off all the temptations of sterilization and gender transformation. Inner freedom cannot be socially established with laws, language regulations, prohibitions on thinking, or social nudging. Freedom, especially sexual freedom, can happen through honest and open communication, the admission of one’s own vulnerability, and the ability to recognize one’s own narcissism. This is my stance today, and I hope that more and more people will resist the impending assault on our bodies and souls by synthetic, pharmaceutically marketable, transhuman interventions.

Claudia Schillinger Films

1985 Fatale Femme (11 minutes)

1986 Dreams of a Virgin (14 minutes)

1987 Das Wahre Wesen Einer Frau (13 minutes)

1988 Zentral-Bad (2 screen VHS (23 minutes)

1988 Drop Out (Video installation with H. Flint)

1989 between (9 minutes)

(Originally published in The Independent Eye Vol. 11 No. 2/3 Spring 1990)

2. Femme Fatale: The Films of Claudia Schillinger (1996)

For the past ten years Claudia Schillinger has been engaged in an alternative erotics, reinscribing the place of female desire in a succession of incarnations – girl with a problem, reluctant partner, femme fatale, mother. Her six films inscribe a trajectory whose shape is less linear than cyclic, begun with the solitary longings of a young girl who tries to re-invent herself for a life outside her own. From there she turns to the dating games of Das Wahre Wesen Eine Frau, the overheated bisexual trysts of between, and finally to an examination of that most forbidden of themes – childhood sexuality – dramatized via In No Sense, and presented in documentary fashion in Hermes. In each she is more than filmer and participant, understanding that the inextricable join of sex and power is founded on the images we maintain, in our personal warehouses of the beautiful, the erotic, the permissible. If her project may be deemed utopian, it is because she imagines that these images might change, and so inaugurate a new cycle of bodily transmission, loosed from the strictures of law which continue to code our most private encounters.

Dreams of a Virgin (14 min 1985) is a materialist’s psychodrama of waiting. Here in the theatre of the self, a young woman assumes a variety of postures, as still borne and unchanging as the architecture she inhabits. In a darkened interior, amidst a maelstrom of slow-moving processing stains, she stands in black against a wall. Suddenly she is joined by a second self in white, who enjoins her to dance, shown in a dissolving succession of freeze frames. Moments of her naked memories interrupt, breast and thigh and arm, before an impressionistic swarm of blue-tinted shots appear, first in negative then repeated again in positive, showing again her standing solitary. As the piano continues its melodic exchange we are witness to a series of veiled enclosures, possible moments where she may re-enter her home, herself. The dance recurs a final time, the dancer in white approaching her own image and passing her hand over it, in order to gain the measure of its discontent, or to find some opening, some aperture into which she may be admitted. At last the dark image passes away altogether, and in the space left behind the dancer passes through it, prepared now to face the uncertainties beyond.

If the events in Dreams are not wholly unfamiliar their meticulous material realization—the scarred and tinted emulsion made to transport these virgin dreams—lift the film from any easy psychological rendering. Its disquieted, pulsing re-photography, its every frame torn from the roots of its expression, enact a solitary ritual which emerges from the disturbed dream of the body. Its quest for opening is also a search for the places in flesh which might be reshaped and re-imagined, its own circle broken to admit the possibility of another.

Fatale Femme (19 min 1985) is a structuralist’s self portrait, repeating a small series of still frames strained through a variety of formal procedures. Once again Schillinger has applied herself to the surface of the film, whose mottled, flickering countenance moves in contrast to the still images they depict. Shot originally in super-8, processed by hand as negative, then rephotographed from a wall, processed again as positive, then slowed in a last transfer to video, lends the whole a generational archeology, each leaving its marks, its claims, against the image. Indeed all that Hollis Frampton had aspired to in Artificial Light, with its cycling series of miniatures made to endure a set of material inflections, shows itself here, but now without the moral didacticism that haunted Frampton’s modernist imperative. Each cycle obtains more of its subject, moving from abstraction to representation, from a corporeal imagination to a persona comprised of flesh. We see a woman lying in bed, a hand gripping a breast, undressing and then her face, as she reconstitutes her solitary for the world, looking back now into the camera in a marked complicity with her own image.

If her first two films evidenced a movement from enclosure to persona, her next would conjure a narrow domestic arena where a couple could re-enact the learned rites of desire. Das Wahre Wesen Eine Frau (What is the true nature of a woman) (10 min 1987) opens with a woman addressing a mirror, her gestures of preparation arrested and released via re-photography, and pursued always by a looming succession of fades which threaten to banish her from the site of reproduction. Cast in an electrifying blue tint, processed by hand and delivered in the throbbing grist of re-photography, we are privy to a collection of small moments at a table between a couple poised on the brink of union. In a circling, structuralist reprise Schillinger offers these moments in a montage which always recapitulates before adding new views to its perspective, protracting this drama of waiting. Their catalogue of events is a list learned in media cliché – hands shaking out a cigarette, a bottle of champagne opened, his hand moving across her thigh, her purse opening-these two made to repeat gestures each will learn to call love. Between her slow-motion smoking and his ambivalent stasis come dreams of touching. She caresses her stomach, and then his head, before jerking it back abruptly, leading us on to another cycle of rehearsals at the table. Midway through the film we are transported to another locale-now it is the man who stands before the mirror, rubbing his face in preparation. Glimpses of her naked waiting interrupt, and build into a masturbatory offering before she folds her hands back against her chest, alone again. His face in the bath rises and falls in the rhythm of coitus before a series of snap zooms make it appear that she is pushing him underwater.

The film closes at the table where a final recapitulation of shots occur. At last she stands by window light, the final shot showing two cups of coffee waiting at the table. Schillinger’s elegant montage sustains tension throughout, the murky sheen of emulsion which strains representation filling the spaces, the unspoken compacts, between the two. These marks of a hand-made image appear as a concretization of desire, seeming to issue from the body of its female protagonist. The title is a quotation drawn from Last Tango in Paris, in a scene where Marlon Brando looks on at the corpse of his wife, slain by her own hand. In despair he speaks to her, “I can imagine the universe but not you, what did you want? What is the true nature of woman?” This question, suspended between the two of them, would not find its complete exposition until Schillinger’s next film, the erotic meisterwork between (10 min 1989).

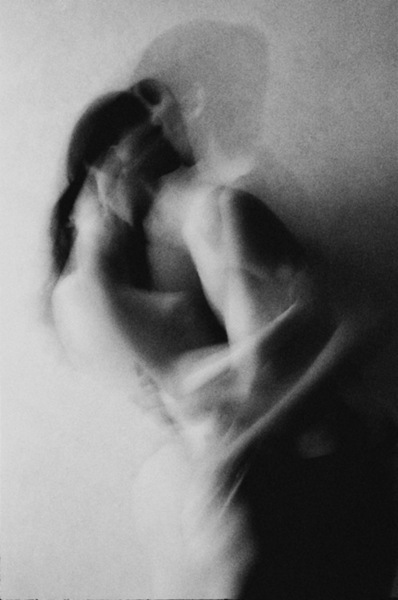

between is a masturbatory idyll, joining via montage black and white images of a dildo wielding woman, two women lying naked together, another before a mirror and at last asleep, turning in solar tumescence. These are framed by colour sequences at the film’s opening and close. Her introduction finds her lying out of doors in a leaf patterned negligee, the camera discreetly turning to reveal a dildo she clasps to her chest. In the end she rises, awoken from her revel, and masturbates against a tree, before appearing at last alone in her bathroom, contemplating herself as her own image of desire. Between her dreamings a succession of stunning erotic images flicker past, in a simultaneous montage which moves towards climax and abandon. If the man is Das Wahre appears uncertain, caught in his own dream of waiting, here it is women who wield the phallus, and inaugurate a frankly unbridled desire. Alternating video freeze frames with a supernal natural light, between reprises a world of vaginal release, abundant in its fecundity, and nameless in its easy traversal of bodies and borders.

In No Sense (10 min 1992) is a carefully wrought, domestic drama which describes the relation of a man and his young daughter. Leaving behind the heavily shaded, emulsified textures of her previous work, In No Sense announces itself in a high gloss colour, lending a naturalistic perspective to these views of home. It opens with a slow motion shot of the daughter rocking in abandon, propelled through space, her hair flying, her face twisted in a paroxysm of joy. The camera finally drops to reveal the origin of her content, she is riding a horse, although the sexual overtones are unmistakable. After the title sequence she climbs into the attic and takes a swing, looking up at the undressed dolls suspended from the ceiling. A naked woman lies in bed, her shaved pubis caressed by a man’s hand. The girl walks into the room, puts her hands over her father’s eyes and he takes her in his arms, all traces of the prone nude vanished. He sings nursery rhymes to her as she rocks on his knee, and via match cut the filmer transplants this scene into a barn, where the singing continues. Later the girl enters the father’s room, opens a drawer, looks past condoms and handkerchiefs and emerges with a small coin. When the father returns home there is a notable tension – is she still there? Will she be caught? But the scene again dissolves into another, the girl rocking once more in the attic where her father looks down at her smiling. The naked woman appears again in bed, the father’s head lifted in abandon, before the girl opens yet another door and walks into a room where someone appears to be lying dead. In this beautifully composed dirge she walks towards her sleeping father and settles herself beside him, looking on at his face and the mystery of his groin curled beneath the sheets. He walks downstairs in his underwear, as if the force of her gaze had banished his usual attire. She appears again rocking on a toy horse while he circles her from above. Then they lounge in bed together, lying languorously as if after sex, though there is no touching in the scene. The shaved woman appears momentarily, before the girl surrenders a last time to the pleasure of her rocking, her burgeoning sexual complicity already somehow complete.

While intimations of incest are everywhere staged, the film is so carefully shot there is no way to know for certain, to separate a child’s normal sexual expression from abuse. Schillinger fills the house with the life of a child, now lent an uncannily sexualized aroma, which turns these domestic inhabitants into metaphors for longing. Her concisely phrased direction, playful point-of-view shots and resistance to the inevitable moralizing which closure enjoins, makes this a rare jewel of a children’s film.

In all of her work Schillinger has proceeded via identification to find a way ‘in’ to the life of her projections, and if her last film is not different, its subject remains easily the most distant from the wiles of her own life. His name entitles the film, Hermes (25 min 1995), a self professed pederast whose only satisfying relations endure with those before puberty. An interview shot in video verité fashion comprises the main of the film: “I wanted to tell my parents my story, so I wrote a book, I wrote for six months. I gave it to them and they finally wrote me back. They considered me worse than a murderer… I try to read the body language so I don’t hurt the boy. Boys whom I’ve hurt don’t belong in my dream. I want a boy who lives out his sexuality. Of course I want to expand this area as much as possible, where our ideas meet. For example, I don’t want to be fondled by a boy if he feels pressured to do it… These relationships, these happily-ever-after Hollywood relationships are faced with a limitation, namely, puberty. Then the child dies. He’s suddenly someone else. It’s like a flower dies… It’s nice to play with a little cock. I’ve got something else, a hanging sausage. And this myth I keep chasing is that one day a young boy or girl will take me across that magic frontier of puberty.”

His narration, delivered by an actor to preserve Hermes’ anonymity, range from self justification, philosophical conjecture, guilt, fear and childhood reminiscences. In wrathful indignation he recounts how his two younger brothers were taken away from him, for fear they too would become gay, though he later alludes to a sexual tryst between them.

Insistently interspersed between his ruminations are grainy, black and white shots of Schillinger and her young child at play. Invariably photographed in bed, they narrate an astonishingly frank sexual complicity, counterpointing Hermes’ subterranean longings. She enacts a permissible, societally sanctioned mother-child bonding while he speaks of a desire quite beyond the law, banned precisely because it threatens the join that Schillinger demonstrates. Throughout the film she asks herself, “Was there a way for me to relate to him? He asked me that. There was something I could share but I didn’t know what yet.” What she shares, of course, are some of these early moments between herself and her only child, who demonstrate that power, release and genital sexuality are very much in evidence at the earliest age.

But despite their interrelation via montage these two scenes remain distinct, Schillinger’s autobiographical embrace unable to account for the devastation, the unleavened impulses, the dark curtain of pre-pubescence which continues to haunt its subject. While she opens its attendant to the possibility of childhood sexuality there remains the question of consent and power, and without the voices of his young amours, rendered here in a series of grainy snapshots, there is no way to accede to the filmer’s single urgent request: to judge. And to judge fairly.

Nonetheless she continues to forge a body of work unique in its insistence on pitting the body of its maker against the trespass of desire. Her erstwhile method, of identification through incorporation, speaks of a corporeal invention, and a level of risk few would dare endure. That she continues to challenge marks her as an enduring light of the fringe, casting a rare luminescence on those untrammeled moments others would let sleep, or bury forever.

Originally published in Millennium Film Journal No. 30/31, Fall 1997