Snapshots by Daniel Reeves

I can’t help thinking how unspontaneous it seems at this moment—to prop open a book of old family photographs and sit at an awkward keyboard trying to breath life back into the past which, although forever here, is also hidden by time. The earliest photographs are 2″ by 2″ black and whites that could almost pass for big postage stamps, with their square frames, crinkle-cut edges and tidy compositions. I will use them to launch this letter of inquiry, moving with their crisply outlined silver halides and chiaroscuro clouds toward that part of my life which is largely hidden; memories obscured by sadness and my mother’s inability to sketch out even the broadest strokes.

It is possible that the shame of her own weakness and irresolution, galvanised by our step-father Milton’s abhorrence of what existed before him, keeps her commentary bound to the litany of how much she loved my father, and how handsome and despicable he was. Oddly enough, I can’t even name this man at the moment. I want to call him John, or Charles, yet I cannot speak with any certainty. Perhaps this is a perfect crystallisation of the choking dilemma I find myself in—to be unable to name or even say the thing which, however dim, is here before you like a tree or a house. It is much like those dust devils found in the desert. You never see plainly, no matter how fast you whip your skull around, since they live only in the periphery of conscious vision. So here they are before me, these slightly browning blacks and blank whites, hidden from view until my brother Tom and I were well into our thirties.

My brother asks: do I want to see any photographs of my REAL father? Who disappeared from view so long ago but could have been living just around the corner for all we know? “Yes Tom,” I said, I suppose I would like to see them, as well as read the clumsy letters of protest he wrote to my mother when she (as the story goes) discovered he had another wife and family. Whether my father was actually married to my mother at the time, I cannot be sure. It has only recently occurred to me what a shadow of half-told stories and hidden plots lies behind me.

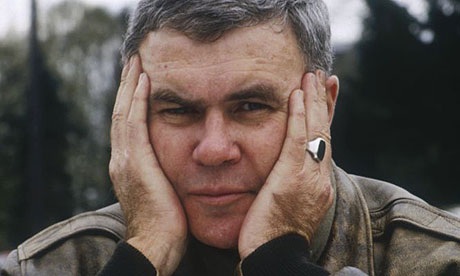

My real father is bereft of any redeeming or endearing qualities, apart from his so-called handsome visage and seductive charm. I conjure up his vanity and deceit in my own deluded wandering. It’s true, we look a bit alike, moulds from the same press. Yet this tiny silver image has an appropriate tilted horizon. It is as if everything on earth were already in full slide, and I am being held up by this wayward rascal in baggy pants, with the clumsy potato-sack ineptitude that men who can’t be bothered with parenting have when they pick up children. In spite of what little I have heard about this boozing womaniser, I really like him. I like my father for his cockiness and nonchalance, the way I also admire detective heroes.

In these little squares stands my desirable mother Suzanne, with her handsome face framed in white-ribbon-decked curls, fine big bones adrift in satin and her shy, cloth coat. With little effort, I can imagine her opening again and again like a warm flower to the men who knew how to love her, but not live with her.

I find three other shots from the same roll. They share the same light, and the cold spring air of temporary grace that precedes the deep well of disappointment and shame that only the truly abandoned will ever know. I am looking at my brother’s early face, usually so animated and intelligent. Here it is blank. As if he is seeing into an altogether different movie or shadow world. As if he already sees the drift and slide in all its vain, glorious tumult and banal horror—the years of oppression and harsh, unfeeling control which were to besiege the tiny forts we built around our hearts to barricade ourselves from darkness.

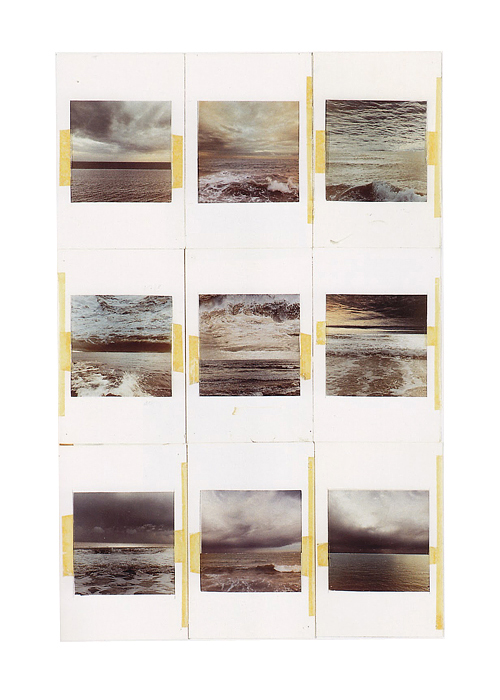

This feeling is the very one Rilke identifies when he writes, “Oh look, it’s in this one, it’s in them all. And yet there is someone who holds up all this falling.” This feeling of being held is in these photographs for me, and not just because they are rooted in who I am. I find it in all old photographs, the older the better. It is born fresh in the Polaroid as it slips into this very morning—only it is not ripe yet. Ripening needs time. How much time is the time bound within the viewer. For me, that is a long time, and it is mostly a black and white time, since colours seem to trick and glamorize vision. Looking now at two new-baby photos, it is clear that the one left un-coloured is full of light and presence, while the other looks like a child who never existed. Gazing at the first, my eyes fill with love for this chubby, smiling face and curling hands. I want to pick him up gently and walk slowly around the room with him cradled in my arms singing the world outside.

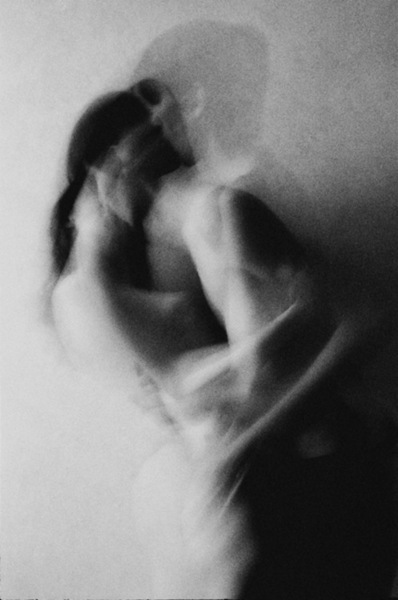

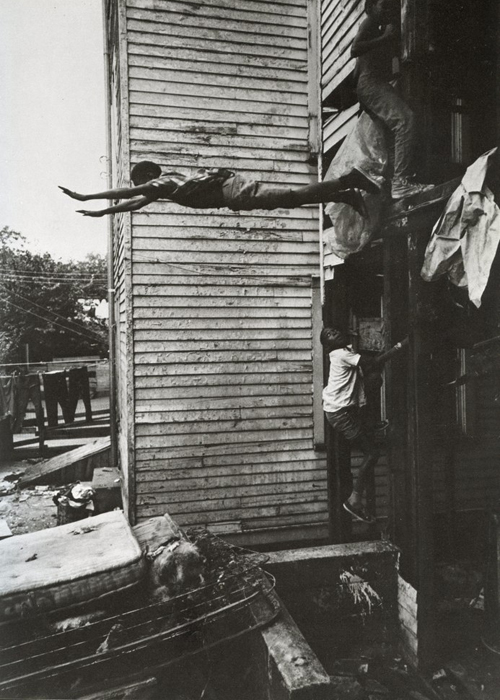

For years I have thought about the boys who died in the water alongside me on the only day I can really remember from Vietnam. My feelings are a mixture of anger, anguish and pure astonishment at my survival. I think of those soldiers as lost children, like those in the limbo preached to my brother and I in childhood. Like us, the boys in bloodied uniforms never had a chance to live, and like these photographs, they remain frozen in time. In my deeper understanding I can see that they have moved on. I have tried to move on as well, but in this moment I can’t help but think of them as glass shattering at my feet as it tumbles from my frozen hand—so quickly without warning. I see them with all their time stolen, snatched from their eternally open arms, and I see myself walking out of this arrested moment and going forward into promise, into light. Only there is something I have left behind with the boys in that crystallised stillness.

The Japanese word for mysterious is pronounced shimpi-teki. This is a perfect sound to describe the qualities found in these old photographs. In this mood I discover the early photographs of my brother. Dressed in white, like a sacrifice or an inmate, this baby appears abandoned, hollering and clutching toward the closest edges of the frame. The camera is barely off the squared perspective of tiled floor, and its gaze charges the room with the tensile feel of a huge mouth about to spring shut. This tension is heightened by the soft, out-of-focus jitter caused by the nervous hand of the photographer during a sluggish sweep of the shutter.

In this photograph I see a wee boy in trouble, and I cannot break into this lost space. As much as I might wish to soothe him, there is no way into this room, for it is locked inside him alone. I have a teacher who says that sometimes it is difficult to be solid. It is hard to stand upright in times of fierce wind and hard weather, when there seems to be nothing at all of substance or strength to cling to. I believe the real lesson is that there is truly nothing to hold onto.

In the christening shot of my brother, born not quite two years after the war in June of 1947, my mother is looking down with a bemused smile at his tiny face dwarfed by the comet tail of an unbelievably large white christening gown. My mother’s torso, shoulders and Slavic head, (adorned with a bad hat and ugly glasses), are encircled by a shiny church window which is held aloft into the vertical rise of the photo by two arches of brick window framing. The secret of the photograph is this mirroring circle of glass that opens into a world left behind. This is another universe, another family cosmology that trails off behind my mother and back through the forties into the Depression and other beginnings.

There are other photographs which are gone, lost, buried or which have otherwise disappeared in the jostled design of our shifting lives. In that window I see another family. There is my mother’s husband, (Charles Derwan I believe), and two children of that union: Robert and Jaqueline. The children walked out of the picture of my dear mother’s life and never turned back. This is the true mystery and, I suspect, the proper key to all that remains so obscure and illogical in this fractured history. It is the story line and the detail of all those times and places that my mother fails to talk about. If my view was wider and more perfectly aware, then all this would just be noise or dim movement. But for someone still walking, still seeking, these rags tied to branches fluttering in the wind must mark the way back home.

Questions: Why, if our father’s name was Merkle, were we brought up, and always registered in schools as Derman? Was my mother, in fact, ever married to this man Merkle? Why did my mother’s marriage to Charles Derman end? Why did the children go off with him to England and the Air Force rather than stay with mother, when this would havebeen the more socially acceptable thing to do in 1940’s Catholic America? Why have the children never made contact with my mother? Why did Milton go through the trouble of using his influence at city hall to get faked birth certificates (which I have used successfully all my adult life), which state that he was our real father? Why would Milton, whenever he really lost control, call us little bastards and the like? Why do Tommy and I look so different, and yet, where similar, we look like our mother? Why was the divorce and dispensation such and long and complicated ordeal?

Lately, it has occurred to me that some of these questions might be answerable by the strong possibility that Mother was having an affair with this Mr. Merkle, and that her first husband left with the children when the affair was discovered. Subsequently, my mother never legally married my father (thus keeping the name Derman, which my brother and I had as a last name while we were growing up). All this will remain unclear until my mother cares to share the truth with us. Somehow, I feel that knowing would put some ground under my feet.

Returning to the album, I find a series of shots taken on a summer day in the park. Among them is my favourite image of myself. It is a symbol of all that I would like to be remembered by. In this photograph I am seated beneath a large, wide-brimmed straw hat, enthroned upon a picnic table with my denim clad legs splayed out in front. Each leg ends in a fat sneaker, and these two look like two mute pages at the court of happy fools. I am looking directly into the lens and holding a can of National Bohemian Beer, a local brand often referred to as National Bo, or in times of urgency, just Bo. The white stem of an unfiltered cigarette perches on my lips, unlit and awkward as a first erection.

You have seen this photo before. It’s the one where the children wield the power symbols; the ruddy Plains Indian boy buried in a mountain of buffalo hide with a feathered pipe and Winchester cradled in his thin brown arms. His eyes are like a frozen lake, and they reel in the future. The top hat and pipe, the chubby hands that grip the steering wheel, the fingers that stroke the flank of the hanging stag or pitch coal into the steam and brass of forward motion. These children are all acting out the parts—filling up the costumed space of those in power, aching for and acting out the future. When I was young and had began to reason, I yearned for the power of the grownups in towering trousers and looming skirts that filled the lonely horizon of my helplessness with their demands and one-way suggestions.

So much from birth until five lies buried or blocked. What do I remember? Going to a night club act with Milton and mom and being given all of the baby chicks that the magician used like paper or balloons in his act. I took them home in a cardboard box where they died one by one during a week long wake to the tune of Tammy’s In Love.

I remember two scenes of anger and violence. In the first, my mother and I are walking downtown when a man in a station wagon is rear ended by a black taxi driver. His car is not really hurt, but the man is consumed by an intolerably powerful rage, and he repeatedly smashes the car behind him by roaring forward and then slamming his car into reverse, with the throttle pressed to the floor. His wife, who is clutching a young baby and crying hysterically, flops about in the front seat like a suburban Raggedy Ann. Pieces of both cars tear away and fall with a great, heartbreaking commotion. The whole scene goes by in a minute, but it seems to linger like the slow motion inferno of Zabriskie Point. Finally, the wild man screeches away and vanishes into traffic, tires howling and burning into the soft, black summer tar. Someone from the dumbstruck crowd yells to the taxi man, “Hey! Don’t worry pal, I’ve got his number!”

I have just turned three. We are in a long line of cars moving slowly and hesitantly through the hazy fields, following a weaving drunk whose erratic driving is keeping everyone from passing, and forcing oncoming traffic onto the shoulder. Suddenly, as the drunk lurches to the side of the road, a few other cars stop. Men emerge. They surround the drunk and yank him from the car. As we pass, the men can be seen pummelling and kicking the drunk man to the ground. My mother says he is getting what he deserves.

In his last poems, written as he approached an early and certain death, Raymond Carver refers to a picture taken two years before he was informed of his fatal cancer. “You open a drawer and find inside the man’s photograph, knowing he has only two years to live. Only he hasn’t found this out yet. That’s why he can mug for the camera.”

No matter how tightly I shut my eyes, or how forcibly I peer into the labyrinth of my faint memories of these early years, I can retrieve only fragments. Half a room, the shadowed parts of a hall, the element of fear from an incomplete scene, the eclipsed pattern of a quilt, many faces devoid of names. Where does the rasa, the sweetness hide? Where is the juice of the thing? I am certain there are rooms bulging with books in all the major cities and universities which would offer a definitive answer to this mystery of memory, but as Rumi says, “Truth is not a matter for discussion.” Thesis upon theory from epistemology to deconstruction and back around the bend in time again. These are shadow studies—bound to language, they are fettered by the expectation of result. For me, what is real must necessarily be signless—without reference or symbol—and while the truly signless cannot be measured or rationally described, it, like all this falling, must be held.

(Originally published in Landscape with Shipwreck: The Films of Philip Hoffman, Insomniac Press/Images Festival, Toronto, 2001)