1. David Rimmer Introduction

(Two night retrospective at Toronto International Film Festival’s Lightbox screening, March 22, 2014)

Walter Benjamin wrote that there are two kinds of storytellers. There’s the nomad, the traveller, the one who wanders. This person carries the stories of one place to another. Perhaps in this carrying and translation, there is also an inevitable mixing of stories, like a bartender, or a cook, or a collage artist. The second kind of storyteller spends their whole life in a single place, and learns the lore, the deepest stories, of that location.

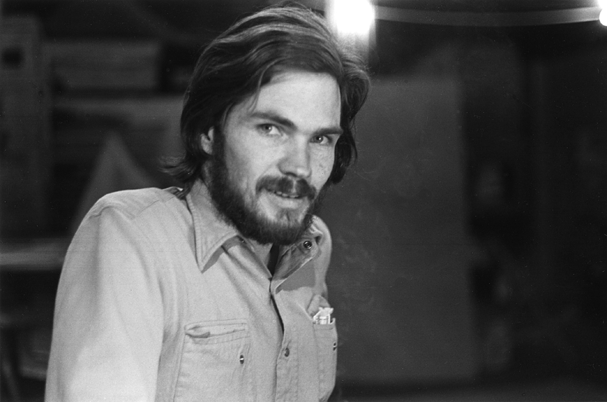

David Rimmer was born in 1942 in Vancouver, a place he still calls home. Is it possible to see in his body of work a history of this port city, poised between nature and culture, the capital of a province whose economy continues to turn around resource extraction and export?

David went to university to study, what else, economics and math, and when we was finished he decided, like so many in that moment in the sixties, to take a trip without a destination. He knew only that it should take a long time, he worked freighters on both oceans, and went around the world, shooting his first motion pictures in 8mm. When he came back a life in math didn’t seem quite so perfect. He went back to university to study English but that didn’t seem “quite right” to borrow his expression, but a radical film artist from Boulder came to visit and showed a long silent movie called Dog Star Man. David recalls, “Although I couldn’t make any sense of it at the time, I thought, “Here’s someone who’s really doing something different.” Can you imagine a family, can you imagine a world, in which this would be the highest form of praise? The greatest good and virtue, the most desirable thing: they’re doing something really different.

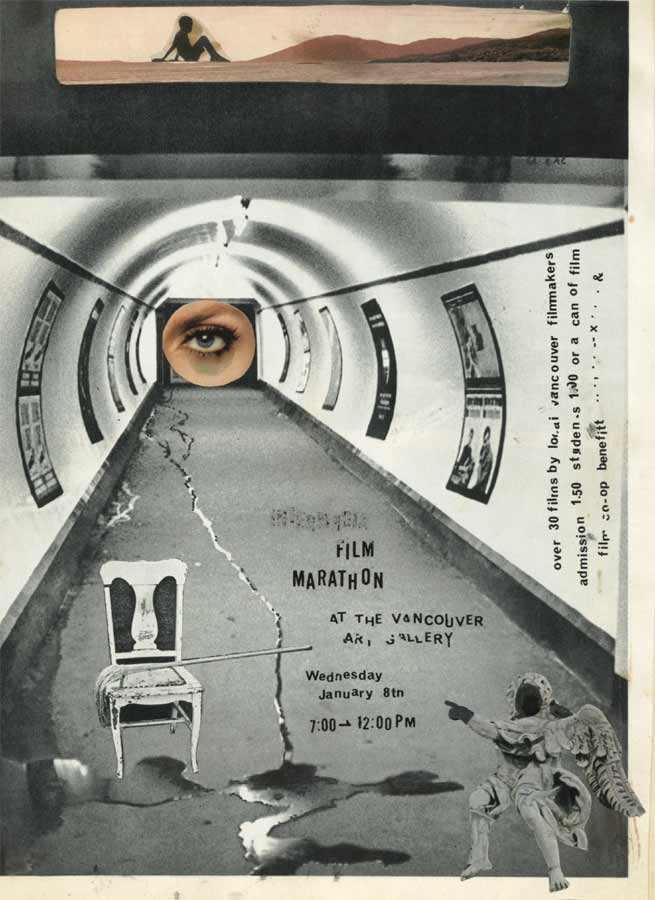

It was around this time that David entered what one might call a second family. I think most artists have two families, there’s the family that you’re born into, and there’s a second family of art and artists. Just like the biofamily, the second family has rules even if they’re not spoken out loud. The rule could be that you have to break all the rules. The rules could have something to do with going as far as you can go, or arriving at your singularity as an artist, the thing that only you can do. For David, I think his second family arrived at The Intermedia Society or Intermedia, which was started by a group of friends in 1967’s summer of love in Vancouver of course. It ran for five years. Al Razutis put on fringe movie screenings, there was a bit of film gear, even a short lived distribution centre. But unlike the media specific artist run centres of today, there were poets and painters, video artists and dancers. The iconoclastic, post-be-bop jazz pianist Al Neil was there, David’s spirit dad, around every corner there was another idea, another unknown and mysterious process.

Intermedia had this crazy arrangement with the Vancouver Art Gallery at the time who would throw open their doors and let the anarchists roll in with their playtime, process-oriented hippie art, and it was here that David began to do projector performances, often using the abundance of found footage available from the always helpful National Film Board. What he discovered very early was the joy of watching something again. There is the joy of discovery, and then the joy of rediscovery. He developed a knack for looking at a small moment of time very closely, very deeply, and primed by his playful experimentations, he developed a feel for what kinds of pictures might bear up to the joys of being seen again and again.

In other words, one of the first lessons of his new family had something to do with attention. The artist brings attention to a moment, an encounter, and then makes a record of that meeting. And the record that the artist shares with us offers not only the marks and traces of the encounter (the scene, the people, the setting) but it’s also a way of sharing a particular quality of attention, the loneliness of the long distance runner, the deeply sustained engagement, breath after breath, frame after frame, that tracks the small changes. When you have a friend for ten, twenty, thirty years, and your friend is telling you the story of what happened last weekend, the story is entirely new, you’ve never heard it before, but at the same time, you can feel the deep patterns at work. Part of the joy of friendship I think is to delight in, to revel in, the small variations and permutations of a familiar life, a life re-viewed again and again, to celebrate, to grant attention to, the small changes of that life.

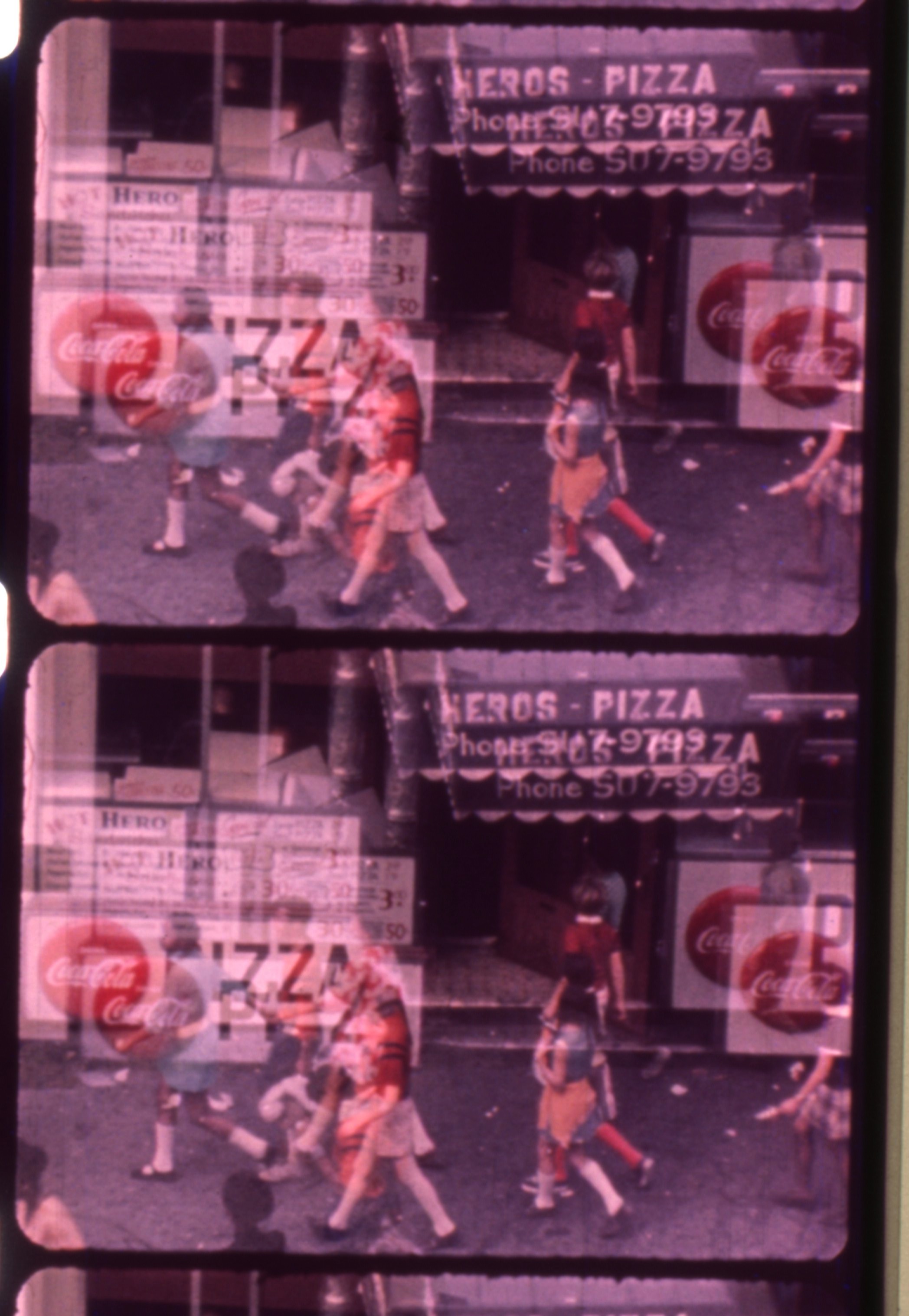

David’s deep attentions and his natural feel for materials produced his first well known body of work which we’ll look at today. In 1970 he made five movies, often taking small fragments of film drawn from the projector loop performances at Intermedia. When it came to producing pictures of his own he looked for restrictions to set him free. He needed a container to pour his attention into. After his furious output in 1970 he moved to New York where he lived in the loft that Mike Snow had shot Wavelength in, it still had the picture of the sea taped to the wall. Later he moved uptown and began collecting views from his window that overlooked a joint called Real Italian Pizza. He has arrived at a bustling centre of the world, there’s a million things going on, but he’s only looking out the window, every day after day, and three years later, homesick, he repeated the trick back in Vancouver’s Gastown to create Canadian Pacific 1 and then 2, shot from different windows in his Gastown apartments. The place I live is the ethical ground of my seeing. It’s the same view, but it’s never the same view, if it was music we’d call it theme and variations. David: “Most of my work since Real Italian Pizza is documentary in some sense.” Tonight we’ll see seven movies made between 1969-74, his early formative and structuralist period.

Let’s peak ahead at the artist’s bio. In the eighties David would take his looped structuralisms, and begin to stitch them together, creating film/video hybrids, cracking the codes of TV, gender roles, language itself. He made a stunning China travelogue, and portraits of artists Jack Wise and Al Neil. In the nineties he made his summary masterpiece Local Knowledge, and in the noughts he started hand painting on film. He’s at work now on a new movie, perhaps he’ll say something about it. Or maybe he won’t. But one of the lessons that Stan Brakhage imparted, even on that long ago screening of Dog Star Man at a Vancouver university that might have raised the curtain, was the importance of what happens before you see a picture. We might call it: making an approach. Stan’s pre-screening talks were so fluid, so wide ranging and intense, that they raised the temperature of the room, they created an edge of your seat atmosphere for the reception of his movies. They were a way of making an approach. Tonight, none of the facts are important, we can feel the details already beginning to fade. And in their place this rarest of encounters, this performance of a film, hurtling through a projector, waiting to be met, to be realized, the gift opened and received, the movie completed only in its reviewing and re-seeing. Did he? Can you? Will we? Is the project still alive? Can we look quickly slowly keenly enough to meet the picture flow before it becomes part of a collective forgetting? Can we rescue these moving pictures from a culture of distraction, see far enough to do the work of this present moment?

David Rimmer 1: Surfacing

The first part of our two-night retrospective devoted to the Canadian avant-garde great spotlights Rimmer’s gorgeous landscape films. David Rimmer will be joined onstage by Mike Hoolboom and the Academy Film Archive’s Mark Toscano for a post-screening discussion on Saturday, March 22 and Sunday, March 23. This programme is rated PG.

The world premiere of the restoration of David Rimmer’s Variations on a Cellophane Wrapper at the 2013 Toronto International Film Festival was the first fruit of a major restoration project — undertaken by Mark Toscano at the Academy Film Archive in Los Angeles — devoted to one of Canada’s most important experimental filmmakers. Rimmer has been exploring the formal properties of filmmaking since the late sixties, employing a structuralist approach that eschews that mode’s occasional tendency towards intellectual dryness by filtering it through a West Coast sensitivity to landscape, poetry and psychedelia; indeed, many of his early films, comprised of a visceral mix of re-photographed found images and looped sounds, were made in the context of Vancouver’s interdisciplinary happenings.

Even though Rimmer’s films are recognized as key works of Canadian experimental cinema, they have not been screened extensively in Toronto for quite a few years. Recent publications, and Rimmer’s honouring with the 2011 Governor’s General Award, has brought back some well-deserved attention to his work, but it is unquestionably the AFA’s restoration project that is the most important endeavour in resurrecting his invaluable oeuvre. Conceived as a status report on this long-term project, these two programmes of restorations and newly struck prints offers Toronto audiences a chance to discover or reacquaint themselves with the early work of one of Canada’s most influential experimental filmmakers. — Chris Kennedy

Part I: Surfacing

Like many filmmakers raised in or transplanted to the verdant wilds of British Columbia, the stunning beauty of the West Coast landscape has played a central role in Rimmer’s work. The films in this programme capture visions of natural beauty both undisturbed (the shadowed patterns of clouds on mountains in the time-lapse film Landscape being one of the most idyllic) and marked by human expansion, as in Canadian Pacific‘s view of Vancouver’s Burrard Inlet, framed by the North Shore Mountains across the water and the railroad that serves as an essential connection to the rest of Canada in the foreground. The programme culminates in Rimmer’s early classic Migration, a tour de force of expressive personal filmmaking in which Rimmer creates a stunningly kinetic relationship with the world around him.

Landscape (dir. David Rimmer / Canada 1969 / 8 min. / 16mm)

Canadian Pacific (dir. David Rimmer / Canada 1974 / 9 min. / 16mm)

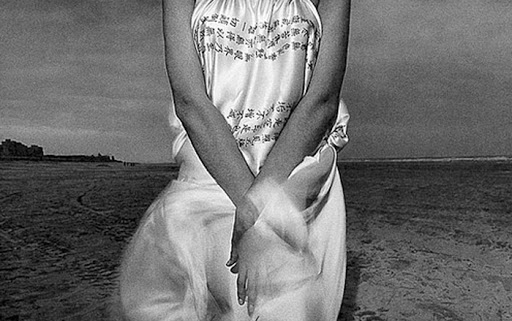

Seashore (dir. David Rimmer / Canada 1971 / 11 min. / 16mm)

Surfacing on the Thames (dir. David Rimmer / Canada 1970 / 5 min. / 16mm)

Narrows Inlet (dir. David Rimmer / Canada 1980 / 10 min. / 16mm)

Treefall (dir. David Rimmer / Canada 1970 / 5 min. / 16mm)

Migration (dir. David Rimmer / Canada 1969 / 11 min. / 16mm)

1. David! (2007)

Tune In, Turn On

When I asked my friend Richard if he felt he was part of the ‘avant-garde’ he took a step back and exclaimed, “Avant-garde! That’s like the original six teams in hockey. It ended when I was a kid.” Oh yes, the fabled avant-garde, home at last in the twentieth century, and raised to feverish heights in the sixties with its dreams of feminism and black power and free love and hand-cranked Bolex cameras to make a picture of it all. We would make our own media, tune in, turn on and drop out. And once we were out, far out, our third eyes would show us the visions of the avant-garde and they would look like home movies. Like home.

Where is our revolution now?

There is a small gaggle of folks still carrying the dream. After all this time bent behind cameras they can shoot a movie without using one at all; they just swivel their heads and watch it come down twenty four times a second. Thirty if they’ve switched over to video.

They’ve managed to live outside a collective looking for how many years now? Their look is already a refusal. It is not television for instance, it is not us, all at the same time, saying yes. It’s me and it’s you, her and him. This is what they believe, these grey hairs, these stooped, balding remnants of revolutions past: that everyone needs to look for themselves. There is no uniform law, no ten commandments or reliable science. If it’s repeatable, forget about it, throw it away and start over until you can’t turn the same number over and over.

Who are they? The ones who don’t fit in mostly, geeks and misfits and it’s hard to keep that up past forty. When you’re twenty it’s charming, at thirty it’s eccentric, at forty a societal danger, by fifty it’s no use, they’ll never learn. When you’re twenty and soaked in enough beer to preserve flesh into the next century and you get up for a naked jog around the bar it’s charming, it’s funny, ha ha, pour the lad another and send him home. Try the same number when you’re sixty and the cops are bundling you into the back of the car, no questions asked. Any child past the age of forty should have the decency to stay out of sight, even in the hardly there scrums of fringe media. Just ask Jack Smith.

Artists rarely have a chance to get old in this country. They give up, or head south, or turn their work into a parlour trick for the agencies if they’re really lucky. Mostly other things get in the way. Like family. Trying to make the rent. Security, dying parents, AIDS, the abortion, it means exactly the same thing in the end: no time to make art. That’s a luxury, an extra. If youth is wasted on the young, then art is not far behind.

Long Distance

It’s late Friday afternoon in Gastown and I’m standing with my friend Alex outside a micro cinema he’s called The Blinding Light!! He explains to me that the window we’re settled against was busted up just a couple of weeks back so that someone could grab a handful of CDs that were sitting on the counter. He tells me this with a voice that leans hard into a couple of words, letting me know that if these strangers were music lovers he’d understand, Alex can understand almost anything done in the name of love. But knock down a big beautiful window like that so you can pocket a few CDs and make ten bucks for the next hit? This is capitalism at its most disappointing.

Who walks round the corner right then but David Rimmer. “Mike!” “David!” When I talk to him he looks at me with eyes that never should have been allowed to get quite that blue, and he looks from a long way away. He’s standing up in front of me and we’re so close I can feel the breath leaving him in even measures, as if someone were inside counting. “Mike!” “David!” I don’t know David so well but he likes to talk like that sometimes, in brief exclamation points. And then he goes far away again. He’s long distance, he’s way out there. Standing here in front of me. Where has he gone? He is trying to pull me into focus from that faraway place and it’s hard. I can tell the dream he’s leaving has to be pretty sweet because of the effort it requires to get him back here, right here, and then he takes all the time that is in his face and covers me with it and we stand in this luxury of time like two kings. Where did all this time come from? At last there is time to speak and to say the right thing and the wrong one and take one detour, and then another because that’s where all the juice is. David knows that so well, the juice is in the detours not the straight lines. If you want it bad enough you stay off the roads. There’s nothing on the roads but other drivers. That’s US looking again, that’s the way WE think, and David’s already left US and WE behind. That’s what makes him an artist, his knack for wandering, taking the unlikely detour. He explores chance systematically.

Making Movies

When David started making movies he would take small bits of other people’s movies, leftovers, really no more than a meter or two of film and he would look at them for a long time. When he was young he already had the knack of looking at small things for a long time.

He wouldn’t make a big production out of gathering, he wasn’t a hoarder or collector, he didn’t need to have everything, there was no set he was trying to complete. He took what was coming to him, and if it wasn’t all that much, no worries, that was fine too.

He was a recycler, working with remnants until the audience could feel it right along with him, holding that bit of plastic in his hands. He might dissolve one frame into the next frame into the next, so you’d slowly watch a barge cross the River Thames, along with a storm of golden dust and scratches (Surfacing on the Thames (9 minutes silent 1970). Or he might make a loop and lay some math on it, showing us a frame for how many seconds, and then the next frame for a bit less and so on, as if each frame were an event, an occasion. Happy birthday frame! (Watching for the Queen 11 minutes black and white silent 1973) Or he might make a loop out of a woman throwing some cellophane on a table and then unravel every possible variation, in every colour and combination of colours. (Variations on a Cellophane Wrapper 8 minutes 1970) The way he could measure time and rhyme it out second after second was like a musician working off a riff, like old Bach sitting down at the clavier running out his variations. David could make the fragments sing.

Hands

David has these large hands and who knows if it’s true but this is the fantasy: he has dad’s hands. If anything goes wrong, if the roof leaks or the TV is broken or the washing machine won’t start, no problem: these hands are going to fix everything. Thanks dad. These hands are also a way of knowing through touch, understanding directly, up close and personal. We don’t need to talk about it, never mind about the manual, the way it’s supposed to be done (that’s more of the WE version), these hands will find a way. For the last four decades these hands have attached themselves to an art of machines. The interlocking gears, the belts and drives, the old world of industrial hopes and class struggle and the birth of the unconscious, all that is worked on up inside these machines of cinema, and David’s hands pass through all that, feeling right at home.

Home Movies

Like every dad he likes to make home movies. How much of the Canadian fringe is home movies? There are the diary boys of the escarpment school, the video narcissists, the coming out movies (coming out gay or nerd or Japanese), the trips back ‘home’ to some far flung part of the (not-quite post-colonial) world. But pictures of home have invaded even the work of hard core conceptual artists like Mike Snow: what else is Wavelength but a long look at home? This is a home that used to belong to David too. As a young artist he did the right thing and rushed down to New York, lived in a big beautiful loft in the village, and when it was time to leave he gave it to Mike Snow. A year later it was on the cover of Artforum.

Home spun. Home truths. Home made. The Canadian fringe is home made.

New York

While David was in New York he set his camera up by one of his windows, looking at the pizza joint across the street. Real Italian Pizza the sign read. All kinds of things are happening across New York City but David makes his stand right there, at home. He sets his camera up and that’s where he stayed, week after week, month after month, always shooting through the same frame. And in the middle of that frame: Real Italian Pizza. (Real Italian Pizza 13 minutes 1971) What a beautiful film it is, thirteen minutes of summer and fall, with the folks gathered or passing by, the police and fire trucks, the hipsters and not so hip, they’re all there. When he gets back to Vancouver he takes an apartment in old Gastown and sets his camera up again. This time he’s looking out over railyard and harbour, with the ocean freighters come to dock and the mountains behind all that. Big weather. (Canadian Pacific 9 minutes silent 1974, Canadian Pacific II 9 minutes silent 1975) David’s running all over the city getting into scenes and falling in love and talking whenever he has to but his camera stays at home, looking out over the docks, shooting when the light is right, or when the fog rolls in, or whenever something catches his eye. He exposes a few frames and then he leaves it alone and goes about his living. This living is also a way of seeing.

Al Neil

It must have been on one of those all night, steady-on-up-to-the-bar occasions when he met Al Neil. A veteran prankster, Al belonged to another generation, more beat than hippie, playing an off kilter bebop piano in a style no one had a name for. Maybe they recognized in each other the same kind of being alone and out of this recognition and friendship came David’s movie Al Neil: A Portrait ( 40 minutes 1979). This one really shook me when I saw it, because I’d seen David do his magic act with remaindered footage, spinning it out into something beautiful and precise. But this was documentary territory, this was the Real, the Other, and all those geek chops, all those knowing dad hands, weren’t supposed to be able to prep you for encounters like this. Usually the fringe folks would obliterate their subjects with technique, just bury them in flash and flicker, but not David.

In this portrait of his friend he leaves out most of the stuff you’re supposed to put in a doc, all the experts and important people telling you how ahead of it all Al’s always been. Or people telling you what you’re listening to and what you’re looking at, parsing the moment. Instead, David films Al close-up playing the lonely piano for a long time. David watches his comrade play, and gives us time to hear him. It keeps on coming at you and it’s not the backdrop for the credits it’s the thing itself. He shoots nearly the whole movie inside Al’s strange ramble of a house. We see the totems he’s carved and for a few moments Al talks his talk in that raspy unforgettable voice, coming through the years and the good bottle David’s brought along to make it smooth. Al’s laugh: like a coffin heading the wrong way. And then right at the end of the movie we see him at a packed gathering in a gallery called the Western Front, and it’s a shock. All of a sudden Al’s up onstage at the head of a buzz and he’s got a little serial music in his mouth, he’s going to start off with some Steve Reich ideas he exclaims, and sure enough he does. But inside a few bars he’s back to playing that strange, tortured bebop we’ve been hearing for the last half hour, and even though it’s running out over the crowd we’re inside the music, we’re close to these familiar notes, we’ve found a new home here.

As an artist who makes pictures David has one great advantage which is that he hardly knows how to talk. Never trusted words. All that wind out of the mouth. He can’t fill in the place his pictures should live by talking himself out of it or talking until the feeling stops entirely. He wouldn’t know where to begin. He keeps his mouth shut and his camera open.

Film and Video

David was never part of fringe media’s cold war: film versus video. He did a few turns with video back in New York for instance, shooting some of the right now with the weight lifting machines that passed for video recorders in those days. So maybe it was no big surprise that he hit the 1980s with a video recorder in one hand and a Bolex in the other. But slowly those tight little film circles he was running as a young man got worked up alongside other kinds of loops, and while these moments never collected into anything like storyland, some idea of purity had been left behind so he could chase down other dreams. David was still looking hard at small bits of thrown away media, but instead of running them through their paces and showing what pictures looked like when they were left to play, he wanted to rub them up together until he had something like montage. And in order to pull these pictures out of the trash pile once and for all he had to get them to look different, to look the way he was seeing them all along, and in order to do that he needed video.

What he was trying to do with his film/video hybrids like Bricolage (11 minutes 1984) and As Seen on TV (15 minutes 1986) was keep himself up on the wire. The truth is, he’d found his way early and got right down and painted his masterpieces in the ten shorts he pulled out his hat between 1970-74. Then he trumped his own trick four years later with Al Neil: A Portrait. Most artists would have the dignity to quit, to pack up and change careers, but David went on, though it took him a few years to find a new groove. He was still committed to the short form; paintings weren’t any better if they took up the whole ceiling. So he lays a snippet of epileptic seizure between day-glo-coloured TV bits until the seizure becomes a comment on televisual spasm which he names As Seen on TV. He runs a loop of sound and picture out of joint until the sound comes all the way back and accompanies the picture again in Bricolage. Sometimes it can take that long, require that many attempts, until you see a picture at all. In Narrows Inlet (10 minutes 1980) he takes his camera out on a boat and click clicks a frame at a time even though he can’t glimpse a thing. He’s caught in the fog and there’s nothing there at all until a sliver of colour appears, and then slowly, oh so very slowly, the fog lifts and the tree line lives again, staring back at the camera with all of its colour and height resolved. Another small miracle of looking.

By the end of the 1980s he’s in China, replaying the last twenty years of his life in the movies, only with Chinese crowds pulling themselves into his lens. Black Cat White Cat It’s a Good Cat If It Catches the Mouse (35 minutes 1989) asks: How do I look? He takes it all in with steady precision, up early each morning to catch the only light worth gazing into, except for the last moments of the day, so he climbs back to catch some of that too, finding his way between sleepers and trains and tai chi circuits. He meets his subject half way, not you over there like a zoo specimen, but both of us inside the cage, checking each other out, making contact. David has a knack for finding the necessary distance. Without that distance, it’s impossible to begin looking. Every day tourists are busy turning cameras on but it’s no use, they manage to record everything without seeing a thing. Most artists, never mind tourists, are still trying to find the distance. David is busy showing us how.

His second great ‘period’ comes to an end with Local Knowledge (33 minutes 1992). It is a reckoning and last stand. Not a movie that could ever be made by a young man, its time-compressed skies and hunters and fishers and motorboat reveries narrate a home movie reading of the west coast. Beautiful pictures, one after another, but more than that. He wants to let go because letting go feels like freedom, only it’s not. David’s been around long enough to know that too. Freedom arrives in the net, the frame. Only when the taboo and prohibition have been drawn is the artist free to play. That’s the sad, long lesson of Local Knowledge. Hard because you can’t smile with the same sort of innocence after that.

David has made many movies since Local Knowledge, though none with its urgency or scale. It’s hard to stay up on the wire as long as he has. No one’s managed it longer in this country. He’s still looking for a way back, trying to feel his way through paint splatters on frozen emulsion, or another good look at the landscape around him, or another fascinated discard of footage. He’s been there and back and knows the only place where he’s worth a damn is moving moments together that don’t belong, looking into faces for a long time until he can see clear through them to the other side. He’s the youngest older person I know. Finally retired from teaching, he can give that old dog a rest and with all that new time settling in him who knows what next?

2. David Rimmer: Fringe Royalty (an interview) (2000)

For more than thirty years, David Rimmer has been making some of the most exquisite work in the fringe microverse. He has the uncanny ability to take small moments — the view from a window, the tiniest scrap of discarded footage — and rework them into panoramas of attention. From the very small he is able to extract the very large. He is led in his choices not by calculation but by intuition; given his luminous body of work, he may be regarded either as the luckiest filmer alive or else as someone who has become a student of chance, working at it, cultivating it the way others reshape their bodies through exercise or tend small gardens. Not incidentally, his work offers a typology of the city he has lived in almost all his life: Vancouver. Its multi-storied histories — its growing industrialization, the divide between nature and culture, the Elite Directory, its love affair with the British monarchy, its Asian ties, and the increasing influx of American television production — have all been restaged in Rimmer’s work. The secret history of the city is written in his practice, though no one would be more loath to discuss it than Rimmer himself, who has guarded with silence his lifelong romance with intuition. In this beginning there is not a word but an image.

DR: I graduated from the University of British Columbia, majoring in economics and math. After graduation, I decided to take a couple of years off to see the world, hitchhiking, working on freighters across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, and travelling overland through Asia, Europe, and Africa. When I got back to Vancouver I realized that I didn’t want to be an economist after all. So I went back to university to study English, though that wasn’t entirely satisfactory. The problem was that I wasn’t a writer myself, and I couldn’t see spending my whole life writing about other people’s work. I needed a more direct involvement with what I did.

MH: How did you get word about fringe film?

DR: The Cinema 16 film society at the university presented programs each week, showing Dada and Surrealist work and European cinema. I had no idea what they were about, but they were more interesting than what I was seeing downtown, so initially I tried to make that kind of film. I had brought an 8mm camera along on my travels and began to make films with a group of friends in a very naive way. Brakhage came to the university to show Dog Star Man and although I couldn’t make any sense of it at the time, I thought, “Here’s someone who’s really doing something different.” While I was pondering his work, a poet friend of mine, Gerry Gilbert, gave me a book by Brakhage called Metaphors on Vision. That book changed my ideas about film. I realized that anything was possible, that there were no rules. I started in a new direction, using the camera in a more expressive way. But I was still working in somewhat of a vacuum.

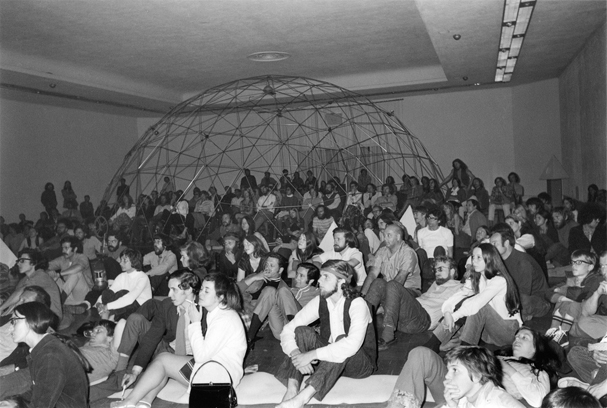

In 1969 Al Razutis came up from California. He’d left the States because of the Vietnam War. Al began bringing programs of experimental or “underground” film into town, and I quickly saw that there were others working in this field, in a tradition of artists’ films that ran back to the Dadaists and Futurists. Al’s shows ran out of Intermedia, an experimental arts workshop set up by the Canada Council to encourage artists to work in interdisciplinary ways. I had no formal training in art, so Intermedia became my art school. We did a number of very large performances at the Vancouver Art Gallery where we combined film, videos, performance, sculpture, music, poetry, and dance. It was a very exciting time. Sony gave us a half-inch black and white portapack to experiment with. The camera came with a razor blade and tape so you could edit, but it left horrible glitches, so we mostly made tapes lasting the length of a roll — about twenty minutes. It was liberating because it didn’t cost anything. I did a lot of installation work at that time; the most elaborate one featured sixty television sets displaying a mix of pre-recorded material, local TV, and closed-circuit work showing other events in the gallery. Some of the monitors had been smashed by hammers, others had small scenes constructed inside the monitors. No one knew anything about video, or ever heard about coaxial cables, so in order to make the connections we just scraped the wires and joined them end to end. This allowed the image to escape from the cables, fly through the air, and wind up on a different monitor entirely. I also made videos that accompanied dance performances.

So far as film equipment went, Intermedia had only rewinds, a tape recorder, and a camera, but no one complained — that’s all anyone ever needed. I didn’t know what the rules were, which was a blessing. We had a lot of old footage from worn-out National Film Board prints and educational films. In some of our performances we’d have a bank of four or five projectors running loops while musicians hit the notes and poets read. I started playing with this loop of a woman shaking out a sheet of cellophane, running it backwards and forwards, putting coloured filters in front of the projector, and that was the beginning of Variations on a Cellophane Wrapper (8 min 1970).

The entire film is made from an eight-second loop, and I worked in a deliberate way to arrive at a fixed form for the loop’s transformation. The first half is contact printed, showing successive generations. You see the original, then a print of the original, then a print of a print, as the loop slowly gains contrast. In the second half of the film, I rephotographed the image using two projectors running simultaneously, one with a negative loop, one with a positive loop. I mixed the two, playing variations like a jazz musician might, introducing colour filters which gave a colour-separation effect. By the end of the film the image dissolves into a flickering abstraction, reduced to lines and shapes. Everyone cut their original reversal film then because the price of a workprint would buy you another roll of film. When I finished putting Variations together I started looking for money to make a release print. I had heard that the National Film Board was giving out small amounts of cash to filmmakers at the end of their budget year (if they didn’t spend it, it would be returned to the head office in Montreal). I called them up and made an appointment to show them my work. I was met at the door by Peter Jones, then head of the Board in Vancouver, and he put the film on the projector. The film had hardly started when Peter began chuckling. I didn’t know what to think. When the film was finished he asked where I had got the piece of stock footage. I knew that it was from an old NFB documentary, but pretended I didn’t know. He told me that when he was a cameraman for the NFB he had shot that footage himself. And then he gave me the $300.

The Dance (5 min b/w 1970) is another film that began as a loop in an Intermedia performance. Curtains open on a stage where a jazz band plays and two dancers come out. I looped their dancing so they perform the same moves over and over. Then the band stops, someone brings them flowers, and the curtain closes. Surfacing on the Thames (9 min 1970) began with an eight second piece of footage showing a boat moving on the river Thames. It was slowed down by printing each frame two hundred times and then using ninety-six frame dissolves to join them. The boat moves almost imperceptibly, but the dirt and scratches and texture of the film move a great deal. This old bit of film had run through hundreds of machines, acquiring a history of projection which my film reviews — I was interested in what was happening on the surface of the film itself.

I made Treefall (5 min b/w silent 1970) as an accompaniment to a dance performance. As the title suggests, it shows a loop of a tree falling. It was projected on a giant screen made of strips of white surveyor’s tape, so the image was visible on both sides. The dancers could move back and forth, right through the screen. That same year I also made Blue Movie (6 min silent 1970). I shot water and clouds in black and white, then made high contrast positive and negative prints. Colour filters were introduced in the printing. It was projected from the ceiling of the Vancouver Art Gallery onto the surface of a geodesic dome twelve feet in diameter. The dome was covered with a porous cloth, and the image was visible both on the surface of the dome and the floor of the dome, which was covered with white foam. The audience could lie on the floor of the dome and look up at the image and also be part of the picture. Gerry Gilbert said it was like being inside your eyeball.

MH: You made five films in a year. Better drugs then?

DR: It was a very high-energy time. The Vancouver Art Gallery was run by Tony Emery, who was very open to any kind of experimenting. Each year he gave Intermedia two weeks to do whatever we wanted.

MH: How did you wind up in New York?

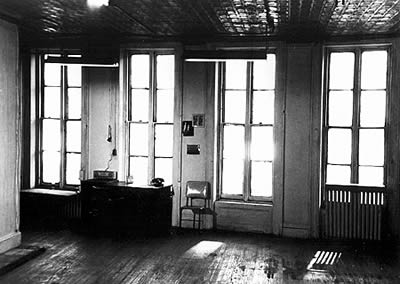

DR: I’d been driving taxi to support myself, then applied for a Canada Council grant. Back then you could only apply for an arts bursary, no matter what discipline you were in. I looked down the list — music, theatre, painting — but no film. So I wrote “film” on the form, drew a little box beside it and checked it off. To my great surprise I received a grant for $3,700. That was enough to live in New York for a year. My wife was a dancer who wanted to go to New York and study with Merce Cunningham. We moved there in 1970. At last I got to see everything that was going on in experimental film because everyone came through New York. The main place to show work was the Millennium Film Theater, run by Howard Guttenplan, and a show there led to an invite by Larry Kardish for a screening at the Museum of Modern Art. I supported myself in New York by working at the MOMA library and as a carpenter for a theatre company and as a freelance cameraman. We lived in Mike Snow’s working loft on Canal Street for a year. It was pretty bare, with cold water taps, a hot plate, and no bath. Mike had shot Wavelength there. At the far end, by the windows, he still had a picture of the sea pinned up. It was like living in a movie. One morning I set off for a bookstore and found my loft on the cover of Artforum. I remember seeing Wavelength back in Vancouver. “Underground” film was in the air, which meant sex and drugs, so the place was packed. But there’s not much sex in Wavelength; it’s a very slow zoom down a loft, and after a few minutes the audience started throwing things at the screen, until finally the projectionist turned the film off.

I made my first documentary, Real Italian Pizza (13 min 1971), in New York. Most of my work since then is documentary in some sense. I wanted to make a film about New York, but I wasn’t sure how. I sat at my window on 85th and Columbus Avenue, looking out at a pizza parlour across the road, and I realized there were all sorts of things going on there — people getting busted, fire engines, passersby, snow falling. I was afraid to go out with my camera in New York, but now I realized I didn’t have to go anywhere. The window gave me focus. I framed up the pizza parlour and locked the camera down for eight months. Initially, I shot ten feet every day at ten o’clock, until I saw that nothing was going on. So I started checking the window periodically, exposing whenever a moment insisted. I shot about five or six to one. The record store next door kept the music coming, so kids were always hanging a groove. I tried to find some music to go with the film but ended up having a rock band in Vancouver make a soundtrack especially for it. Later, the film showed in Toronto at the Funnel. While it was running they hooked up a telephone to the sound system (the phone number was on the storefront) and they called, asking for me. You could hear the pizza guys asking at the counter, “David Rimmer? Is there a David Rimmer here?”

I found an old 16mm camera in a flea market, bought a keystone projector for three dollars, and made my own contact printer. I passed the original footage, along with the unexposed stock, through the camera. I took the lens off the projector, and replaced it with a cardboard tube which ran through a can with a light bulb in it. That was the printing light. I was working with another eight-second film clip showing people at the beach in the early part of the century. That became Seashore (11 min b/w silent 1971). I broke the loop down into smaller sub-loops before running it through the printer. Sometimes it would jam, and sometimes I would deliberately jam it by grabbing the film and ripping the sprockets off. I recut the material to make a dance out of it, because dance has always influenced my work. The loop is covered with stains and watermarks; like in Surfacing, I was interested in the physicality of the shot, making the material visible.

I got involved with video again in New York, working with Rudy Stern and John Riley, who were running Global Village, an alternative news-gathering outfit. We shot with black and white portapacks, and at the end of each week these images were presented on a bank of sixteen colourized monitors in a loft on Broome Street in Soho. One week, for example, we shot the Italian-American Civil Liberties Union, who were protesting the use of the word “mafia” in The Godfather. They felt Italian-Americans were being unfairly stigmatized. Everyone knew that Joe Columbo, one of the most notorious dons in New York, was behind the protest. We packed off to the news conference and found the major networks already set up, but they threatened to walk if we were in the room. Columbo said he’d give us a private interview later, so we came back and turned him onto portable video — he’d never seen a rig like ours before. It was funny and scary at the same time. These guys looked like central casting’s idea of the mafia, with their slicked-down hair and suits and a lawyer hanging over everything. That afternoon we interviewed another protest group called STAR, the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries. They were pushing an almost identical list of demands, so at the end of the week we ran the two stories together in a collage. Along with some footage of Abby Hoffman, that was the news for that week. Most film artists considered video beneath them. I remember Stan Brakhage saying that video is one of those mediums that might never be an art form. I stopped making tapes after that, feeling I’d exhausted its very limited possibilities. We didn’t care what happened to the tapes after they were shown, because video wasn’t about later — it lived in the time of its recording.

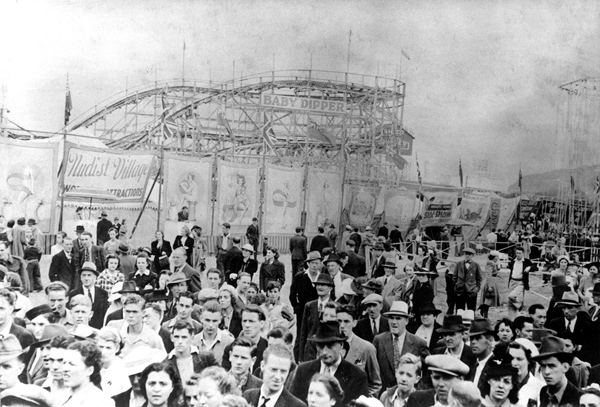

When you’re working with found footage, you always know where to look. I’d chance by the trash bins at the lab at the right time, and there were flea markets on Canal Street right outside my front door. Watching for the Queen (11 min b/w silent 1973) uses just one second of stock footage from a documentary about the Queen’s visit to Canada. It’s my most formal work. The first frame was printed for one minute, the second frame for half a minute, the third frame for a quarter of a minute, and eventually the film returns to normal speed. The shot shows a crowd of people looking at something, which in the original footage is the Queen passing by. The arrested speed allows you to look closely at each individual in the crowd, to scan the frame. When I work with stock footage I look at it over and over again until it starts to speak back to me, rather than applying an idea of what it’s about at the beginning. I work intuitively, wondering how I can make order out of it. Do I impose some formal arrangement, or let it flow and see where it goes? I try to give the image room and wait for something to insist itself.

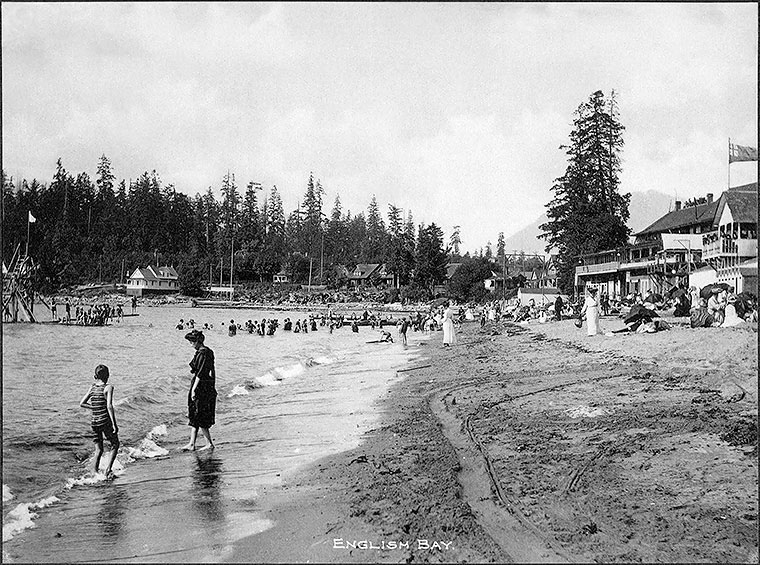

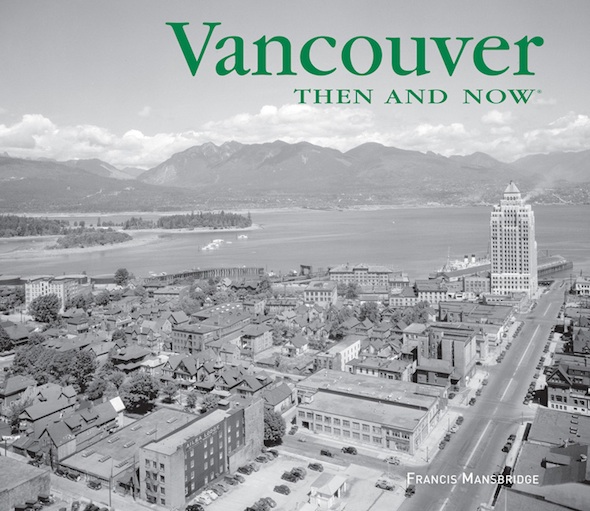

After three years in New York, I got homesick, missing the mountains and wildness of Vancouver. I moved back to a loft in Gastown, the oldest part of the city. That’s where I made Canadian Pacific (9 min silent 1974). Like Real Italian Pizza, it’s a window film. My windows looked out onto the rail tracks, the ocean, and the mountains. I locked my camera down for about three months and shot whenever something occurred. Boats passed, snow fell, trains arrived. There’s one person in the film. Then I was kicked out and moved next door, and set my camera up again at a window that was two flights higher than the first one. That became Canadian Pacific II (9 min silent 1975). I sometimes show them as a double screen, they contain the same elements but with a slightly different view, both shot in the winter. Now I’m living about a block away and I’m thinking about doing a third film in this series.

MH: You’ve worked as a teacher most of your life.

DR: When I came back to Vancouver, I got a job at University of British Columbia teaching film production with a projector, a camera, and one splicer. That was all you needed then. I stayed about three years as a sessional lecturer, earning just enough to keep food on the table, then got into a political argument and left. I ended up at Simon Fraser University where Razutis and Patricia Gruben were teaching. I stayed there for about four years, got into trouble there, too, and quit. Then I went down to the Emily Carr School of Art and Design, which was looking for someone to teach video. I gave myself a crash course and signed up, and that’s what I’ve been doing these last twelve years.

MH: Your next film was a bit of a departure, a very intimate portrait of a friend.

DR: Al Neil seemed to have been making art for so long that he’d started before anyone knew the meaning of the word. He was a jazz pianist and a collage/assemblage sculptor. He’d begun years and years earlier and I’d known him for a number of years. He was an important person in the scene, really sticking with it through all sorts of adversity, always continuing to surprise and amaze us. I proposed doing a film about him and he said, “Sure, man, do it.” Al Neil/A Portrait (40 min 1979) was my first sync sound film — a mix of interviews with Al, his piano playing, and images of his sculptures and home.

Al played bebop for years at a bar called the Cellar near Main and Broadway. Later he rejected all that, determined to find some other way of playing music beyond bebop, which he felt had become too predictable. He went off on his own tangent, combining the spoken word, projections, performance, and music. The film stays pretty tight on Al — one close-up follows another until the end of the film, when the camera pulls out and you see him in a social space, at a concert. The beginning also shows Al at a concert but you can’t tell, you don’t see anything but Al and his piano because that’s all that was real for him when he played. Behind him there’s nothing, just a void, a blank. And all those notes filling in the spaces. One morning during the filming, I asked him some silly question and he said, “Man, I want to tell you about my mother dying,” starting off on a long ramble about the funeral and sharing the limo with other members of his family who he thought were also a little bit dead, and then I ran out of film. I changed magazines while the sound kept rolling because Al wasn’t in a state where I could say, “Al, wait.” I just had to let him go. So I wound up with picture some of the time, and then no picture, and then picture again, which created a dilemma when editing. I tried every kind of cutaway, slugging in some black leader just to keep sync, until I finally realized that the black leader was fine. This happens again near the beginning of the film when Al runs down a story about early jazz, finally pausing to ask, “Hey man, did you run out of film?” After I finished the film Al thought a lot about dying. The doc had told him, “Al, your liver’s really shot, you gotta stop drinking. If you stop I’ll give you three years. If you don’t, I’ll give you a year.” Al said, “I’ll take the year.” During his performances he’d project slides of his liver and talk about how much time he had left. But he’s still alive today, playing concerts and putting on shows. Being Al.

The other portrait I made was about the painter Jack Wise. It was called Jack Wise/Language of the Bush (45 min 1998). Jack was trying to get to the same place as Al; both were on a spiritual quest. Al’s way involved excess. He took drugs and alcohol, whatever could get him closer. Jack used discipline and meditation, finally becoming a Buddhist and learning the Sutras. When I met him in the late 1960s he was studying calligraphy at a very deep level; eventually he went to Tibet and took up with a Chinese master. His free-form calligraphy was about letting the brush speak. He also painted very formal mandalas. I saw him intermittently and we’d talk about making a film. A couple of years ago, Jack called and asked if I was still interested. When I told him I was he said, “Well, you’d better hurry, I don’t have much time left. I don’t know if I can make it through the winter.” There was no way to get funding for the film, so I rented a DV camera and set sail to Denman Island. But a quarter of the way there I realized that I couldn’t steer the boat — the rudder had broken in the middle of the ocean. I turned around and sailed back to Vancouver using an elaborate series of curves, barely making it back to the dock. When I phoned Jack he quoted me something of the I Ching: “Difficulty at the beginning means success at the end.” I repaired the rudder and returned, spending a week with him. Jack had a rare blood disease which made him very anemic and weak. He could only paint for a couple of hours each day before he had to lie down again. I taped him working and talking. He’s a very articulate talker, like Al Neil. He’d seen my earliest work, and I’d seen his, so there wasn’t a lot of discussion about what we were going to do. Or how we were going to do it. We trusted each other. Then I returned to Vancouver, roughed up an edit, and was rejected by the Canada Council. Without anywhere else to go, I went to the National Film Board, which gave me enough money to go to Victoria and shoot Jack’s delicate paintings on film and to put the whole thing together. By that time Jack was dead.

MH: Did watching your friend die make you reflect on your own end?

DR: Jack looked forward to the adventure of dying, feeling it was the end of a cycle. While he had deteriorated physically, he was sharp in his mind. He knew he was dying and was very accepting of what was happening. I hope that when I go, I’ll be in the same frame of mind.

MH: How did Narrows Inlet (10 min silent 1980) begin?

DR: Every summer I sail up the coast to Storm Bay, an isolated community on Sechelt Inlet. Nearby is Narrows Inlet, site of an old logging camp where many pilings have been driven into the ground and remain sticking out of the water. I sailed in at night, anchored my boat off the pilings, and fell asleep. When I woke at dawn, the whole place was surrounded by fog, so I couldn’t see a thing. I started shooting a frame at a time, and gradually the fog lifts so you can see the pilings and shoreline. The boat drifts back and forth at anchor, which is reflected in the shooting. I exposed two or three rolls, and, while editing, saw that it was moving too quickly, so I printed each frame five or six times to slow it down. That became Narrows Inlet.

MH: It looks like line drawing at first — charcoal marks against a white page.

DR: The fog softens everything. The fog and the sea. It’s boatcam. I have a forty-two-foot-long two-masted sailboat now, and I lived on it for a year here in Vancouver, docked out in Coal Harbour. But when my partner got pregnant, she said she didn’t want to have a kid on the boat, so we moved back to Gastown.

MH: Bricolage (11 min 1984) finds you returning to found-footage loops, only now several fragments of footage are cast into relation with one another.

DR: Bricolage has three main images and three minor ones. The first shows an old television set with a woman saying, “Hello. Hello.” The loop was in very bad condition because of the splices and scratches. I ran it alongside a slide projector that beamed an outline of a circle onto the image, like the site of a gun or camera. I shot these two off the wall. That’s followed by a couple of shorter images — one shows a woman taking off her false leg. The second main image comes from a documentary on juvenile delinquency. A man walks to a window and smashes it, then another man comes out of a door and punches him. There are two main sounds, the punch and the window smash, and they trade places over time. The sound begins in sync and then drifts with each repetition, until the sound of the window smashing coincides with the moment of the man’s punch. The final image was taken from a black and white television commercial. A woman holds a piece of glass up to her face, moving it from side to side. One side of the glass is clean, the other dirty. I did some very complex optical printing involving mattes and bi-packing to join this image with a shot of a brick wall breaking apart. Her negative image appears in the white parts of the brick, her positive in light sections, and there’s a great deal of colour separation. It’s a deliberate parody of an earlier work, Variations on a Cellophane Wrapper.

MH: Your source materials share no obvious centre, yet they all work as an ensemble. Can you talk about how you bring them together?

DR: I’m always collecting stock images, pictures that resonate with things I’m thinking about. Theoretical ideas perhaps. Although I don’t want to be illustrating theoretical ideas — that’s a deadly form of art making. The images come together in an intuitive way and reveal their meaning sometimes despite my intentions. Until I see an image, I can’t tell whether it’s going to work. I can’t call someone and ask for a picture of an exploding car. After finding something, I typically relearn it a frame at a time through optical printing or video processing, working the image up into something that speaks back to me.

MH: Tell me about As Seen on TV (15 min 1986).

DR: Video had made great technical advances, so I returned to it in the eighties. As Seen on TV, Divine Mannequin, and Local Knowledge were all videobased works transferred to film. All of As Seen on TV was transformed through video processes like chroma key and luma key, shifting the texture and timing of the image. The central image shows a naked man lying on the ground who looks like he might be masturbating. In fact, he’s having an epileptic fit. I found him by chance in the middle of a medical documentary on television. The film opens with the Toni twins, who were quite famous when I grew up. Whether in magazines or television, one used the right shampoo, the other the wrong brand, and together they demonstrated the difference. As the film starts they move through a door and enter a steamy humidity chamber. The camera looks into the room through a window that steams up, which the twins occasionally wipe off. After spending some time shaking out their hair, they emerge, looking to me exactly the way they entered. Other images include a man jumping through a fire hoop, a Busby Berkeley clip showing a chorus line of women with great phallic bananas, and a test for the first sound movie from Edison, in which two men dance while a third plays the violin.

MH: The recurrent figure of the male epileptic, prone and twitching, seems analogous to the television viewer. He’s alienated and alone, surrounded by spectacle.

DR: I wouldn’t call him the viewer. I showed it to Kaja Silverman, a feminist academic, who loved it and said it’s all about male guilt. I said fine. It’s about gender representation, how the sexes are portrayed in media.

MH: Along the Road to Altamira (20 min 1986) looks like it was shot entirely in Europe.

DR: Yes, my wife at that time was in Amsterdam for a dance performance and we decided to drive down to Spain to see the cave paintings in Altamira. I wrote the authorities asking permission to film the caves and they refused, which was good because going into the caves was so magical I’m glad I didn’t have my camera mediating what I saw and felt. I bought a super-8 film about the caves in a nearby gift shop which I used — though the only reel they had left was in German. On the way to Spain, I wanted to visit the cathedral at Rouen where Monet had done one of his series of paintings. He’d make ten paintings over the course of a day, a kind of time lapse in paint. I went to the cathedral looking for the spot he might have painted from. I found a likely building which turned out to be a museum. I asked the curator if I could shoot out the window and he said by all means. But there was a large French flag in the way, blowing back and forth, obscuring and revealing the image, and I slowed it down using step printing. The film arrives at the caves, and the German voice-over describes the cave’s discovery by a young girl whose curiosity led her to the ancient paintings inside.

MH: Tell me about Divine Mannequin (7 min 1989).

DR: It uses just three images, which are video processed then transferred back to film. The first shows feet running; after keying out all the white in the image, I keyed in pure white. By some magic, which I couldn’t duplicate, it looks like a pencil drawing. It was actually shown in an animation festival, though it’s not hand-drawn at all. The second is two large golden balls which rise in front of some Italian architecture and are caught by two hands. The third is a nearly white outline of a man’s head wearing a pair of glasses. The film is about different kinds of energy: physical, sexual, and spiritual. This energy moves up through the body from the feet to the head. I conceived of this film while I was running my first marathon. It’s forty-two kilometres so you have a lot of time to think. On another day, I was running through the rain along Spanish Banks up onto the long hill that rises up to the university. When I reached the top, soaking wet from the rain, I leaned on a bicycle rack to stretch my legs and saw a piece of paper lying on the ground. The text described a religious practice in India. Inside the temple stood a wooden statue of a goddess; a male worshipper could actually insert his penis in order to commune with the spirit. Inside the hollow statue, a young girl with sandalwood oil would facilitate the devotional act. This found text called the wooden statue a “divine mannequin.” I felt that my film was a divine mannequin, because it brought together different parts of the body, letting the energy rise through them. I put the paper in my pocket, ran home, and titled the film. I made another version as a video installation with three monitors stacked one on top of another. The bottom monitor shows the feet, the middle monitor has the gold balls rising, and the top monitor shows the man’s head. I blew up the text and laid it up beside the monitors. Each of the three images was on a loop, and every minute or so the loops would dissolve into the golden balls and the sound of footsteps.

MH: Black Cat White Cat It’s a Good Cat If It Catches the Mouse (35 min 1989) was also made in the same year.

DR: I took my Emily Carr students on a field trip to China with scheduled visits to the Beijing Film Academy, the Sian Film Studios, and the Shanghai Animation Festival. This was six months before the Tiananmen Square massacre. We showed our work to students who laboured under a rigid and hierarchical system, apprenticing for years before they could use a camera, whereas our students were given cameras on the first day of class. The work we showed was typical art-school fare: very experimental, political, sexual, off-the-wall — completely unlike what students were allowed to do in China. They were amazed. I decided to make a film while I was there. I brought my Bolex and a bag of film and documented what I saw, getting up early and going out in the streets. I didn’t have a plan, this wasn’t political analysis; I was looking with fresh Canadian eyes at something I’d never seen before.

MH: What did you see?

DR: I saw a lot of people looking at me, because I was white and had a camera. They were the focus of my attention and I was the focus of theirs. I searched for fixed frames where I could set the camera down and let people walk in and out of it. Like the Scientology storefront in Beijing. I also recorded sound there. The radio ran English language lessons, and in order to teach the words, they made up stories which were unintentionally hilarious. A woman meets a foreign student on a bus, they discuss schooling and she shows him where to get off. As he’s leaving she asks his name and he says, “John Denver.” And the woman calls out to the driver, “Stop! I have to get off now!” I used some of these stories in the film, along with sounds collected independently by my colleague Dennis Burke. He’s a musician, composer, and sound designer and we’ve worked together on a number of films since.

MH: I saw echoes of a lot of your earlier work in the film, which suggested that while you’d arrived in a new place you had brought familiar methods of seeing the world. I thought Black Cat was not so much about China, but about how looking or subjectivity is carried across borders.

DR: Filmmakers develop their own vocabulary over time, like a painter or a musician, which becomes the way you look at the world. The work comes out of this view, this kind of attention that is entirely personal. After I premiered Black Cat at the Experimental Film Congress in Toronto, I went back to my hotel to find the TV filled with scenes of the Tiananmen Square massacre. I realized my film had a different context now, and wondered how I could acknowledge what these students were doing. We had met many of them on our trip. Were they in jail now, or dead? The next morning I woke to the sounds of protest, and outside my window was a march of Chinese- Canadians heading to the Chinese embassy. I joined in and a Chinese student handed me a piece of paper, with transcripts of the last broadcast from the Beijing English language radio service. They said, “Our colleagues have been murdered in the Square,” and appealed to the world to stop the massacre. They signed off by saying that due to political relations in Beijing this was all they could report. I included this text at the end of the film.

MH: Tiger (5 min 35mm 1993) is your only film in a 35mm format.

DR: One of my students found a 1927 camera at a junk store, and I lent him the $300 to buy it on the condition that I could use it for a year. I shot widescreen landscapes, water and waves, and also included a scene from a Mexican documentary showing a caged tiger. This film was in 16mm so I cut out all of the frames and taped them onto clear 35mm film with the sprocket holes visible. The caged tiger is like the taming of the landscape.

MH: Local Knowledge (33 min 1992) feels like a summary work, combining time-lapse photography, found footage loops, and careful framings in an episodic venture into knowing.

DR: The title came from my life as a sailor. When you sail on the coast here you have to be very careful about rocks and currents, always consulting the charts. “Keep the little rock to the left as you veer towards the shore … ” But sometimes when you arrive at a small harbour the passage is too complex to describe in a book, so they say instead, “In order to enter this harbour local knowledge is required.” This knowing comes from the people who live there. The film is about the knowledge one has about the place one inhabits. It begins in Storm Bay, where I spend my summers, then moves out into the world, and eventually returns. The ocean is a strong image in the film; I shot from the boat, allowing the winds and tides to transport the view. Women emerge from the water in found-footage moments, women as muses and sirens. The centre of the film is a jog around a large ten-foot rock on a mud flat. As I circled the rock the camera was always pointing towards the rock’s centre, recalling the Muslim pilgrimage to the great rock of Mecca. This circling achieves a kind of peace.

MH: What do you think about the state of the art?

DR: I think there’s less interest in experimental film now, but people are more tolerant because they’re exposed to different kinds of work. But experimental film — a term I never liked — is not as different now. The mainstream has co-opted a lot of technical things that were being done, so it’s harder to surprise people. Experimental film used to exist in opposition to the mainstream, but that’s no longer happening at a formal level, only in terms of content. Different kinds of stories are being told, and different kinds of people are telling them. But experimental film doesn’t really exist any more.

For me, cinema begins with the image, and one of the problems with cinema today, with experimental cinema, is that it starts with the word rather than the image. This problem is even worse in video. I think we’ve all seen, or been forced to sit through, long videotapes with a lot of indecipherable text rolling over the top without any visual appeal at all. Somehow the image has become something that accompanies the word, a kind of visual aid — almost a slide show to go along with a lecture. This kind of filmmaking has been bothering me for a long time. I see a lot of these illustrated lectures masquerading as films whereas I don’t think these should be films at all. They should be talks or books, or something in a different form. They don’t really have a place up there on the screen. And this problem is compounded even further: we have the word being translated into the image, which is bad enough, but then, at the end of the film, they want to translate it back to the word again. There are a number of reasons for this. There seems to be a fear of the erotic power of the visual image, an inability to deal with this image on a direct level. Many feel a need to neutralize the image, to translate the image to another medium, the convenient one being, of course, words. There is an impetus to analyze, interrogate, demystify, and ultimately sanitize the image in an attempt to reduce its erotic power to something more manageable. Perhaps it’s that way with a lot of things today. We want mediation, a Reader’s Digest version of reality. I think as filmmakers we must look at our images. I feel a lot of filmmakers don’t see. They can’t see their images at all. They’ve no idea of what they’re putting up there. It’s in their heads and not in their eyes. Audiences must listen to the images and try to experience them in a more direct way. Resist the temptation to explain them away. As soon as you’ve explained an image it’s forgotten. Dead. That’s the end of it. The beauty of an image is that it cannot be explained, it’s ambiguous, it can hold many meanings at the same time which continue to reverberate long after the film is over.

MH: You don’t like talking about your films.

DR: Once you try to explain an image, it takes something away. If I were a poet I would do it; wordsmiths would feel comfortable. But asking filmmakers is not always a good idea. Do we ask musicians to explain what all those notes mean? Ultimately, it’s the image itself that has the power.

David Rimmer Filmography

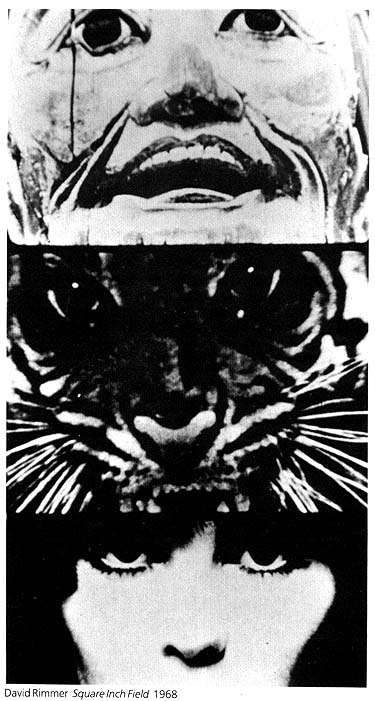

Square Inch Field 13 min 1968

Landscape 8 min silent 1969

Migration 11 min 1969

Blue Movie 6 min silent 1970

The Dance 5 min b/w 1970

Surfacing on the Thames 9 min silent 1970

Treefall 5 min b/w silent 1970

Variations on a Cellophane Wrapper 8 min 1970

Real Italian Pizza 13 min 1971

Seashore 11 min b/w 1971

Fracture 10 min 1973

Watching for the Queen 11 min b/w silent 1973

Canadian Pacific 9 min silent 1974

Canadian Pacific II 9 min silent 1975

Al Neil/A Portrait 40 min 1979

Narrows Inlet 10 min 1980

Bricolage 11 min 1984

Sisyphus 20 min video 1985

Along the Road to Altamira 20 min 1986

As Seen on TV 15 min 1986

Roadshow 22 min video 1987

Black Cat White Cat It’s a Good Cat If It Catches the Mouse 35 min 1989

Divine Mannequin 7 min 1989

Beaubourg Boogie Woogie 5 min 1991

Local Knowledge 33 min 1992

Tiger 5 min 1993

Under the Lizards 77 min 1995

Jack Wise/Language of the Bush 45 min 1998

Traces of Emily Carr 25 min 2001

Originally published in: Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada, ed. Mike Hoolboom, 2nd edition; Coach House Press, 2001.

3. David Rimmer’s Vancouver (1994)

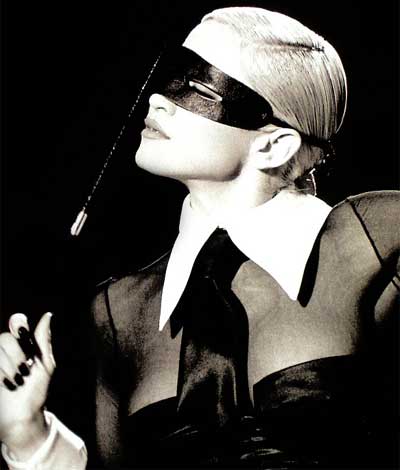

She stands motionless, covered in a fine haze of sweat and blonde ambition. Around her six men, naked except for g-strings, preen about her garters, long arms reaching from her stiletto boots to the crucifix lost in the foliage of her bustier. Her hand caresses the length of her décolleté, her head hurled back in a paroxysm of excess. In an instant, she seizes her sex and thrusts it boldly towards 80,000 Japanese teenagers. They don’t speak English and the performers speak nothing else but tonight the differences of language are set aside. They reach for her with the understanding that genius is not a gift but the way out one invents in desperate cases. The year is 1989. The city is Osaka. The woman is Madonna.

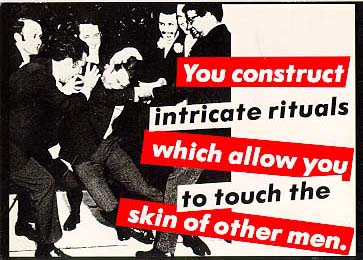

Over the course of the past decade Madonna has turned from pop star to corporation, assuming the roles of author, performance artist, gay rights activist, movie star and business mogul. Her tireless incarnations have proved an irresistible lure for the mass media’s cult of personality. But apart from her gender and her boundless relish for the invention of life before the camera there seems little in this story to separate her from dozens of other media icons—be they presidents, royals, fast horses or entertainers. But in her pursuit of iconicity, Madonna has consciously drawn ideas and images from generations of vanguard artists—restaging formal tropes, themes and motifs held dear by a marginal imaging practice. These would be most succinctly applied in a genre she would deploy with an imprimatur all her own: the music video. Designed as advertisements for records, these short, narcissistic class fantasies found a champion in America’s MTV and quickly blossomed into a global phenomena. To the astonishment of all those who had been involved in the sixties reinvention of cinema—in the liberation of an apparatus that had for decades remained the near exclusive preserve of a monied class—they found that the grammar of personal invention, a grammar of discarded film stocks, marginalized sexualities and meditations on the apparatus—all this had been pressed into the service of a budding genre whose express aim was marketing. These personal gestures had been drawn by film artists working in a singularly eccentric fashion with little attention or reward, outcasts even from an art milieu that remained the preserve of objects that could be bought and sold. Seemingly overnight this long ignored rhetoric would appear again, now reduced to the dimensions of a television set, beamed to audiences undreamt of even in the most utopian imaginations of the avant-garde, now made to watch as decades of discovery seemed effortlessly converted into the hype surrounding new record releases. For evidence one need look no further than Madonna’s most recent recording effort, Erotica. The video produced for its title track is a virtual catalogue of avant-garde gestures in film—the handheld camera, layers of superimposition, grainy, step-printed images of the forbidden, recycled found footage, flare outs, stroboscopic lighting and form cutting all conspire to ease Erotica onto a shelf alongside a pantheon of other vanguard works in film. Indeed, having delivered it to the offices of MTV it was promptly banned, adding to its transgressive aura of forbidden sexuality and dangerous practices, another arena avants once claimed as their own.

The postmodern temper of the eighties have collapsed traditional distinctions between mainstream and marginal cultures—for so long the war cry of an undernourished vanguard of artists inveighing against the reifications of privilege that fueled the dream factory. But now the Other has turned to embrace its bastard kin, proving once more the resilience of capital in its ability to absorb difference and turn it towards a common ideal: the commodification of experience. Now that the fringe has been co-opted into the electronic vomitorium of multichannel television which way does opposition lie? How is it possible to construct an image practice that might resist the feeding frenzy of commerce as it roots out undreamt territories, worlds not yet imagined in its colonization of a double architecture—one below ground, one above? And if such an image could exist, what would it look like here, in the aqueous portal of Vancouver—for two decades home to one of Canada’s most prodigious efforts in the arena of fringe cinema? In answer it will be necessary to turn back, not in hopes of celebrating the good old things but in unravelling the bad new ones..

Everything in history appears twice – the first time as tragedy, the second as farce. Karl Marx

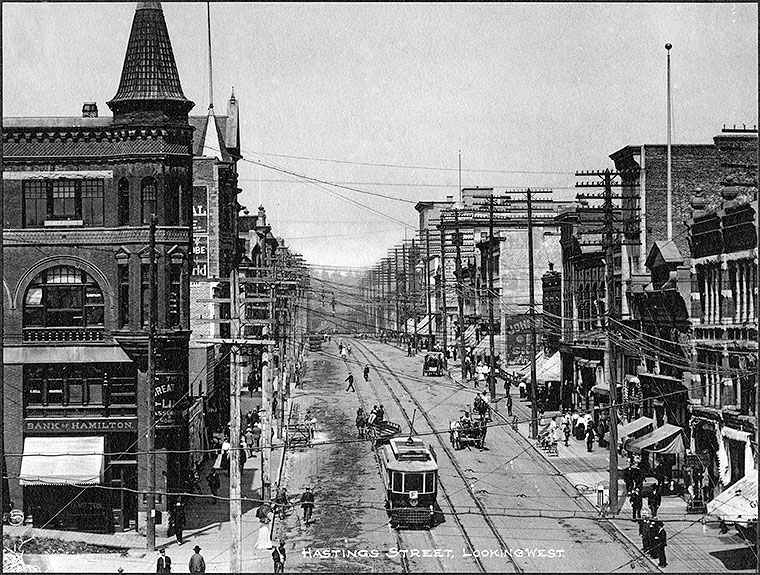

He was born David McLellan Rimmer in Lion’s Gate Hospital, the bleached Catholic erection that continues to overlook the suburban sprawl ranging over the bulk of the city. His parents arrived in 1923—in a period between the wars that provided impetus for the city’s establishment as a major trading port that would fuel a century long expansion. The Rimmers arrived in Vancouver when it was still an aspiring port of call, “Terminal City” as it was named by the men who had driven the rail line cross country. While a few hundred workers had gathered near the Burrard Inlet to work at the Hastings sawmill in the early 1870s, just a couple of decades later their number had pushed beyond a thousand anticipating the arrival of the rail. These citizens would incorporate their number into the City of Vancouver, a city which would number 27,000 residents by the turn of the century, and 120,000 by 1911. A decade later it would grow to 163,000 and by 1931, having swallowed the neighbouring municipalities of Point Grey and South Vancouver it hosted a quarter of a million inhabitants.

Before the rail track merged its western setting with Canadian markets to the east, Vancouver’s port was joined in trade with the United States, home to 60% of its exports, and to England which took nearly a third of its exports. BC’s salmon canning industry set up offices in Vancouver, and the massing Prairie population proved a lucrative market for the province’s fruit and timber trade. Banking interests, insurance firms and industrial concerns from the east arrived in Vancouver to set up shop early in the twentieth century. Government capital in upgrading and establishing port facilities would make Vancouver the busiest port in the country by 1930, two-thirds of its traffic directly tied to wheat. The opening of the Panama Canal gave west coast wood access to markets in the east and beyond the Atlantic. Lumber and wheat figured chiefly, along with canned salmon, metals, fertilizers and fish meal.

The 1930s and 40s witnessed a decline in the use of the port as global depression, prairie drought and the Allied preference for North Atlantic shipping routes each rang their toll. But in the fifties the port grew alongside the global economy to which it remained so dependent, and by the early sixties Vancouver was once again the pre-eminent trading port in the country. Though there was little indigenous manufacture, the twenty five years after the second world war were dominated by exports of minerals and forest products, the latter accounting for half of every dollar earned in the city.

By the time Rimmer had graduated from the University of British Columbia with majors in economics and math, Vancouver had become Canada’s third largest city (after Toronto and Montreal), an exploding metropolis whose colonized economic base would nonetheless seek indigenous expression in an art practice reared beneath the benevolent slopes of the Coast Mountains. For if the identity of its vast neighbour to the south had been founded on the Hobbesian premise of a contract amongst equals securing them from anarchy, a contract that would inspire a revolutionary war, a pioneering spirit and laissez faire capitalism—then the citizens of Vancouver would need to look elsewhere for their sense of themselves, for an identity that seemed as much a function of geography as a question of history. As Northrop Frye would have it, the problematic of a Canadian identity is less “Who am I?” than “Where is here?”—that is, an attempt to account for the vast and overwhelming topography of a largely unsettled surround. To this question, Where is here? there have been few replies as elegant in their summary understandings as the filmwork of David Rimmer.

At the age of twenty six, having dropped out of Simon Fraser University’s master program in English to become an artist, Rimmer found work at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation—the state sponsored television network designed to convert the 5,000 mile sprawl of Canadiana into the alternating currents of prime time. This electronic mirror would continue to founder beneath the phenomenal success of an American tutelage whose wares were in easy reach of the 85% of the population that lived within a hundred miles of the Canada-US border. Network programs beamed at large American markets in Seattle, Detroit, Chicago and a host of other cities stationed near the 49th parallel spilled easily into a voracious Canadian clime already accustomed to American movies, themes and stars. Even today in the video stores that score intersections across Vancouver, Canadian films may still be found in the “foreign” section, while American work assumes the bulk of the retail area.

Forced to compete with its American neighbour, the CBC decided to mimic the proven formulas of the networks, offering its population a retinue of generic sitcoms, talk fests and cop shows. Apart from its journalism and sports broadcasts it has never taken hold, and continues to rely on state purchased programming from the States to bulk up its ratings.