Mourning Pictures (1999)

Ghost Stories

The Blood Records: written and annotated by Kim Tomczak and Lisa Steele is a ghost story, a tale of love and legislation, whose specters call from the other side of history with Hamlet’s last words: Remember me. Like all ghost stories, this one offers passage back into an underworld of dark roots, where plagues and war appear as convulsive echoes of the present, grown familiar despite our traditions of forgetting.

Every ghost story is a history lesson. And if their ends are foretold—all histories end in death—the inexorable movement fascinates, each moment of a life granted meaning by this looking back, this hindsight of remembrance. In being able to answer at last the question which stalks each of us—how did he die? How did she die?—we are able to answer with greater conviction its counterpart: how did they live?

Blood Relations

Every ghost story is a family story, arborescent, flourishing with uncles, great aunts, forefathers—generations of a name rooted in the land, and finally indistinguishable from it. Blood Records is dedicated to the mothers of its makers: Mary Virginia Steele and Marie Collette Tomczak. While the circumstances of their lives are worlds apart, they are joined in one tragic purpose: both would contract tuberculosis, suffer detention in their adolescence, contemplate their mortality in state sanctioned isolation. Both would eventually survive this plague, which would claim the lives of millions, grow old enough to marry, raise children who would one day meet and co-author a body of work dedicated to video art’s eternal recurrence. Video art remains the road not taken by television, which insists that there is only the present, offering flow in place of information, erasure in place of history. Lisa Steele and Kim Tomczak are working underground, in the land of their mothers, below the threshold of an unbridled visibility, miners of the repressed, raising to light questions which trouble the relation between bodies and the body politic, citizenship and flesh. They are ghosts in the machine of state.

Necropolis

In ancient Rome, the dead were buried and their final resting place marked with inscriptions, much like today. In Europe’s fifth century this practice fell out of favour, and care of the dead was assumed by the church. As the town’s spiritual centre, grace could be measured by the distance between the deceased and the altar, nowhere could one find an individual marking or elegy. In the thirteenth century, notions of a collective fate gave way to the modern notion that the individual might find their own destiny, the peculiar truth which they alone embodied, reflected in their death. Cemeteries, long considered unnecessary, came back into fashion. Between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, in the twilight which separated the embrace of death and the will of the living, death was increasingly attached to the erotic, depicted in countless paintings and books of the time. While death had long been considered part of a life cycle it was now understood as something outside, standing in opposition, as a rupture in the natural order. It became a place of madness and mystery, a final orgasmic shudder which would leave the world behind. In the Romantic period, this fixation with the erotic would be sublimated once more, to conjure new ideas of beauty, joining the end of an individual with a rare refinement, purified somehow in this convulsive initiation. And death which had long been a solemn commonplace, became the site of a radically new kind of grieving, fresh outpourings of emotion accompanied bedside vigils, the intolerance of separation occasioning a new form of passion.

If private property had found its way back into the afterlife, the twentieth century would bring one more profound shift in the uneasy relation between the living and the dead, begun in the United States and soon spreading across Europe. It was the death granted us by the beginnings of modernity. Death as a secret. A death of whispers and denial. A death separated, as far as possible, from lives which must maintain their steady course towards the pursuit of happiness. In place of ritual: industries of death. Technologies of enlightenment. Hospitals and sanitariums. Doctors and scientists. Death as a temporary failure of science.

Tuberculosis

Named consumption in the fourteenth century, tuberculosis—from the Latin tuberculum (a small swelling)—became a plague in the last two centuries. Thought to be a disease exclusive to the lungs, its most typical symptoms included coughing and fever, and a languor that seemed to foreshadow death. It was a disease of artists and poets—of Keats and Shelley and Chopin—and became in the early turn of this century part of a new chic. It promoted a look of wan pallour denoting sensitivity and refinement, illness managing to unlock the tired habits of the everyday. Travelers of the underworld, these intrepid adventurers would wipe the doors of perception clean, bearing in their postures of exhaustion the cost of liberation. The muse, it was felt, lay waiting behind these bleached figures, who might step at last beyond the bounds of the known world, where only genius and madness belonged. Its symptoms of fever were held to be part of an inner fire which would cleanse the body, purify it through the crucible of this disease. If there was only one way to enter this world, there were infinite ways to leave it, but none conjured the beatific, self-transcendence of tuberculosis, which sweated away the dark corporeality of the body in order that it could be re-made into a ready portal for the divine.

Transparency

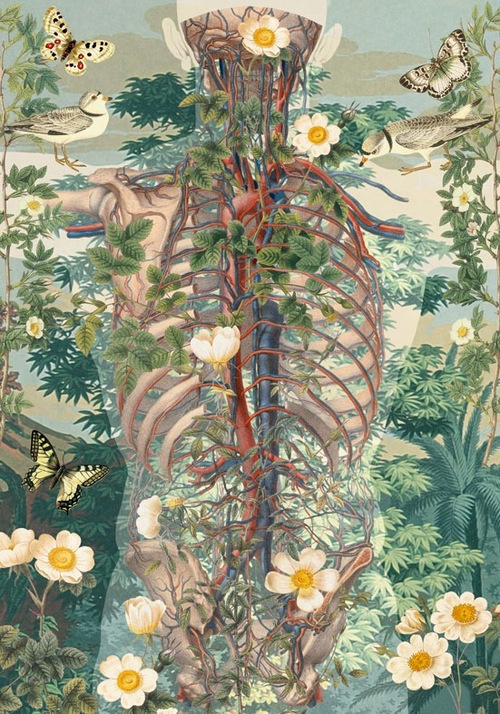

Through the miracle of the x-ray our bodies appear to us for the first time, granted at last a vision of that metropolis of organs and tissues wherein lie the secrets of personality. Nudity is no longer naked. In traveling sideshows at the turn of the century, x-ray machines were one more attraction, so that each might return home with a reminder of that foreign state we call the body.

X-rays are part of the surveillance arsenal Blood Records aims at its hospitalized subjects. Miming the medical gaze, the video camera pans slowly over these patients, pouring over their flesh for signs of recovery or regression. But not content to show only the outside of their charge, Marie, the young heroine of Blood Records, appears often in the twilight of projection, hands opening to reveal knots of muscle and bone, her belly a tangle of intestines. Using slides to illuminate what flesh works to contain, her body is turned inside out, so that the gaze of science and the state may enter her completely, begin its procedures of regulation and discipline in a surveillance each of us would learn to extend to ourselves. If science were to succeed in ridding civilization of this plague, then its scrutiny must be one we would all carry out, on ourselves, at every moment. The ubiquity of today’s video surveillance cameras—which record bank machines in Tokyo, traffic violations in Berlin, building entries in Vancouver—appear natural because they make manifest an eye we have already turned towards inwards. The eyes of medical science would initiate a new period of self-consciousness, and a new body, marked by grammars of pathology and a new morality.

Marie speaks of her possession by science

“You saw the people coming back from the special surgery and they had a scar that was so long it looked like they’d been cut in two and stitched back together again and you were told over and over that it was nothing really. Nothing. Just a little bit of bone removed. Until the night before the operation when they wheeled you into the room where the movies were shown and you got a chance to see how much they actually took out. And you could see there wasn’t going to be much left on that side and it made you feel funny, like you had a story in that part of you that was being told by someone else now, but from now on it would have a different ending. You couldn’t even write it anymore even though you still lived there.”

The Cure

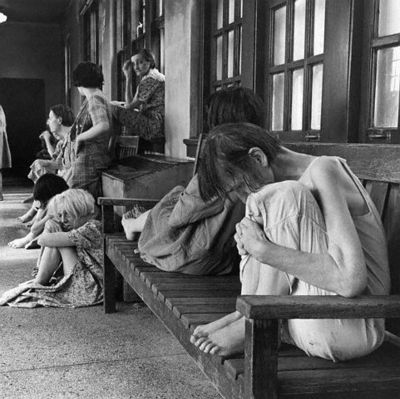

Tuberculosis was held to be a disease of dampness, inflicted by a wet city which had come to reside in the body itself, and so its cures came in the form of a pastoral retirement—to dry and isolated places where the lungs could regain their composure. Much of The Blood Records is set in Fort Sans, Saskatchewan, constructed in 1917, where patients could devote themselves to doing as little as possible. If popular mythology held that TB was an illness borne of an abundance of passion, its cure was designed to instill in the body an almost purgatorial state of recline. Steele and Tomczak revisit the sanitarium with actors and crew, restaging in their tape the small gestures which comprise a day waiting for its own end, where cycles of appetite and consumption are carefully monitored by staff physicians. Children are raised from sleep, served meals, wait for moments of fever to be sponged away. Adults write alone in their beds, play checkers, drink milk—all with an overlaid text which appears like a prescription written over these prone bodies, each hour of the day assigned a task and a place to perform it, so that the power to re-arrange the body could be inscribed directly onto time itself, organized now into profitable durations, and supervised with a total visibility. Here is Rousseau’s old dream of the transparent society, where any hint of darkness has been banished, any zone of the unknown conquered, in order that its citizens may appear to one another with the irresistible force of consensus, the sanitarium a living ideal of the new democracy, and the new human being.

The Church of Illness

“Schools and poorhouses extended the life and regularity of the monastic communities to which they were often attached. Its three great methods — the establishment of rhythms, imposition of particular occupations, the regulation of the cycles of repetition — were soon to be found in schools, workhouses and hospitals.” (Discipline and Punish by Michel Foucault, p. 149)

Marie’s Story

Marie is admitted to Fort Sans in 1944, suffering from tuberculosis. Her brother joins the army and dies shortly after arriving in Calais. Her family is French, but because English is the rule in the sanitarium, her language begins to erode, some children lose their origins altogether. She falls in love with a soldier, and with his smell of the outdoors, always busy writing what turns out to be a history of wartime press censorship in Canada. He has survived the disaster at Dieppe, and so knows better than any that the untold stories are the lives of friends, comrades, relatives. That history will decide who will be remembered. He writes so that memory will have a life outside his body.

At night, she discovers him having an affair with one of the nurses, already promised to someone at the front, someone like her brother perhaps. And while “he always seemed to be passing through… he just seemed to have a touch of the germ and it didn’t seem as if he was going to have to stay long,” he dies, while she, who always looks frail and coughs blood in the night, manages to live.

A Video by Lisa Steele and Kim Tomczak

The Blood Records: written and annotated is a 55 minute videotape completed in 1997. Classically structured with a prologue and three acts, it narrativizes the first great plague of the twentieth century: tuberculosis. Begun in the fields which surround the sanitarium of Fort Sans, its tumbleweed rendered white through overexposure, the screen appears as the blank apron of the past before stories enter to give it shape, underscored by blues maestro Leadbelly singing TB Blues. The first act features a montage culled from educational films which pit two spaces against each another: the intimate corners of home (scrubbed to a Hardy Boys shine) and the cool interiors of the science lab. While home is figured as the site of contagion, doctors and scientists work to uncover the source of this mysterious ailment. The stentorian voice-over, hang-over of the documentary form Grierson would popularize in Canada during the Second World War, offers a familiar mix of information and moralizing, warning its viewers about the perils of reception.

The educational films which comprise this first act have been deftly assembled to rehabilitate the mythologies which underlie the unintended kitsch of their original material — the origins of a public health in personal duty, the conflation of enemies abroad with microbes causing illness. Remarkably, this sequence ends with a doctor prophesying the end of tuberculosis, which vaccination has long since made routine. It is impossible to listen to his studied optimism without hearing the word AIDS—that one day the AIDS crisis will be over—that science will deliver us from one more threat of contagion and keep us safe from one another.

The videomakers turn then to the capitol of Saskatchewan, using aerial pans of the legislature and newsreels showing the swearing in of Canada’s first socialist government under Tommy Douglas. It was Douglas’s radical vision which demanded that health care be extended to all Canadians. Commissions were raised to study the population (over half the children in the province were found to be infected by TB), mass x-rays performed, resources pooled to provide treatment.

The second ‘act’ is set in the sanitarium where patients are viewed taking their rest cures, these quietly observational moments underscored by a haunting violin measure and joined by white flashes, incendiary moments of white fever punctuating repose. Superimposed titles narrate the day’s regimen, as doctors and nurses confer, check x-rays, prepare the morning’s meal.

“5 am Patients wheeled back into room from balconies

6 am Milk pasteurization plant begins operation

6:15 am Kitchen staff prepare breakfast. Over 300 staff for 350 patients.

9 am Morning rest cure begins. During rest cure, patients must not read, talk or listen to the radio.

11:15 am Free time. Patients encouraged to work with their hands.

11:20 am Patients encouraged not to worry

11:25 am Complete co-operation ensures recovery

Midday meal”

Weightless pans lend the viewer the eyes of a body gripped in fever, as if these re-enactments were being watched over by ghosts. Nurses pad silently in white uniforms delivering milk and meals, while the patients wait, read, play checkers, stare out windows, never far from the crisp white linen of their beds. The mood throughout is haunting and elegiac, despite the utopian curatives of a new science, it is difficult to shake the feeling that the end of the world is not far.

The third act begins in darkness, with the voice of Marie, committed before adolescence to the sanitarium, recalling her experience from the far shore of the present. Family life appears in colour vignettes, posing for portraits, or gathered to eat before her brother sails off for war. Over her recollections the dominant formal trope is a virtuosic superimposition, moments of found footage erupting from prairie fields or the sanitarium, these places of waiting become a stage for reflection. Like the patients themselves, this is a landscape of ghosts longing for remembrance. For mourning.

Marie’s Last Line

“This moderate feeling has become familiar to me. It is now all I allow myself to experience, even in moments of great joy.”

Originally published as: “Mourning Pictures” in “The Blood Records written and annotated” (Exhibition Catalog), Oakville Gallery, 2000

Kim and Lisa (2001)

I might as well come right out and admit it: I admire them. Respect them. No, it’s more than that, I hold them up a little higher than the rest, this dynamic duo, this primal couple of Canadian video art. They are the partnership. The firm.

The truth is, I can’t keep up, especially with Lisa. She rolls the one-liners out of her mouth like she was born to the task while I fail to rise to the moment she presents like an endless gift, inviting me to join them, as they have asked so many others before me. Why do my words seem a distant country in their presence? I think it’s because I am keeping a secret, hoping for their acknowledgment, for some word of ‘us,’ you belong here, come inside, though it’s something simpler than that in the end. I long to become them. Both of them.

Around each moment a frame.

You never find the word “Kim.” You never overhear someone saying “Lisa.” It’s always Kim and Lisa, like a tattoo, a brand. Arriving at the opening, speaking at the conference (Where haven’t they been? Where aren’t they now?) they enter the room as one person, filling in each other’s sentences. Hardly a phrase breezes past without one of them offering a sidelong glance, the left and right sides of the brain checking the neural uptake, the electrical field that joins them at the mouth. And in mine. Kim and Lisa. The busy, tireless, and entirely absent centre of my new world.

Around each moment a frame, and inside it an image.

Once upon a time they were the enemy. At least for those of us lost in the ferry dust of avant cinema, huddled together in the twilight hours of a medium scarcely a century old, but already about to be overthrown by its electronic twin, video. We were the last stand, the faithful believers, clinging to the utopia of our pessimism, the certainty that only youth can allow, the belief most of all in materials (The grain! The emulsion! The apparatus!). This final threshold would be replaced, in the years to come, with another (The End of Painting for instance), and there are others still waiting their turn. Each generation must invent the end of the world for themselves.

“Kim and Lisa” (even then it was the same, the names were inseparable, who could imagine the Mona without her Lisa?) were not video artists, or video distributors, they were video. In other words, the feared ones, the new order that would take everything we cherished and turn it into nothing at all. They were the revolution, and we were going to do everything in our power to stop it from happening. Though as it turned out, all the power we had was in our dreams, small dreams growing smaller, and they were never part of this struggle. I don’t even think they knew it was going on. We were shadow boxing, knowing there was an enemy out there somewhere, and if we kept throwing punches, we were bound to hit something. Ourselves for instance.

Around each moment a frame, and inside it an image which can be seen.

Incredibly, film is not yet over. Kodak continues to profit from its death throes, though the margins of gain grow narrower each year. The writing, as projectionists like to remind us, is on the wall, and the differences between film and video seem part of some arcane debate, like those papal bulls reassuring the faithful about the amount of real estate left in the place upstairs. Surely, I can hear you ask, no one, not any reasonable, thoughtful person, could have taken any of this seriously? But we are each of us condemned to the thoughts of our time, condemned to be thought through as mediums, apertures of the present. If Kim and Lisa never enlisted, it was because they were already on the other side, both had glimpsed something in the obscene bulge of the television monitor, the terrible image quality, the inability to edit, the appalling sound and constantly shifting formats. They were busy holding another kind of candle, another kind of light, and soon enough most of us found ourselves, slowly and by degrees so small they couldn’t even be measured, coming over to their way of seeing things, until one day we all woke up together in the same house.

How long will it take, years or months or weeks, before we hear the first rumours that video is dead? Not from me anymore, having lived too long past The End already, and certainly not from theirs. Kim and Lisa. Speaking at the anti-censorship rally. Organizing a cabal of artist run centres to share warehouse space at Bathurst and Queen, and then another at 401 Richmond Street. They are the hosts and we are their guests, and their genius is that here is a father who we don’t have to kill, slowly and publicly and without mercy, and a mother who doesn’t need to be rejoined with her son. It’s not that kind of family. That was the other place, the one they left behind years ago, not chasing a dream, but living it.

Around each moment a frame, and inside it an image which can be seen only by the one.

They didn’t teach us anti-Oedipus with paddle and cutting block. They showed us instead. This is the word we learned from them. Not them but us. Ours. It’s ours now. Unlike the coterie of private dealerships that mark the European artscape, underlined every now and then by the accumulations of capital and attention housed in museums, Canadian showcases are more usually artist-run affairs, makers and committees of makers shoring up decisions with hardly a thought for markets. The auction block for contemporary Canadian practice is a lonely place, but the state sponsored (if they’re lucky!) federation of small dispersed centres ensures that the real estate for art is more available than ever. AIDS activism, diasporic reflections, questions of class and housing, language and identity have been the ongoing currencies of exchange and debate, and these have arisen, inevitably, out of questions of community. It’s true, the best known Canadian artists (the exports, the brand names) have arrived with monographs and museum shows, but most continue to make and exhibit inside art communities.

Much as I would like to marshall an army of experts, the ones for whom talking is knowing, to attest to the value of Kim and Lisa, I can’t. The language of legitimation: take, eat, this is my theory. Official statements from the long march of progress. Remember the Chris Burden commercial which showed just three names? Rembrandt, Picasso, Burden. Most art writing hopes to illuminate, but also to offer lineages in sightlines of the past, the pedigrees of value which might provide the place where judgment may be rendered. Is it any good? The language acts of Flash Art and October provide relief at least from the vagaries of gossip. But in a community of familiars, how does writing function after all (no matter what its form: the critical essay, the review, a private email rave) except as gossip? In the end it’s all I have. I longed for the isolation of my beliefs, for tradition and the individual talent, but slowly yielded to them. The machine of Kim and Lisa. They were not only the dreaded spectre of video, but also avatars of the anti-Oedipus, a post parental, post solitary communion with the muse, insisting from the very first that art and its ideas would be born out of community. Confronted by their example and invitation I couldn’t manage to hold onto the fact that around each moment there is a frame, showing an image which can be seen only by the one… I tried not to resent them for it.

Vtape was founded in two stages, the first saw Rodney Werden, Colin Campbell, Lisa Steele, Clive Robertson and Susan Britton form a sort of co-op and publish a catalogue of their work. All five of these artists were formally at Art Metropole but withdrew for reasons Lisa could go into in more detail. Then in 1982 Lisa and I discussed the idea of a more inclusive model of distribution. Lisa and I ran with the idea and formed what we now have. Interestingly this was made possible by the desktop computer advances made in the early eighties. Kim Tomzak

In Canadian vid art terms, back in the day means 1982, when Kim and Lisa formed Vtape, an artists’ video distributor schemed up to make the work flow and which, incredibly, all these years later, they still manage, not alone now but nonetheless, week after month after year, they’re still there. Making the phone calls. Writing out the cheques. Not the loneliness of the long distance runner but The Hosts. The long weekend of their life.

They started collecting work, though hoarding wasn’t their task, the need to fill in every blank spot in the stamp album. They spoke to friends and visiting artists, put the word out until the work started to drip back through the cracks, and it’s still dripping. At present, another tape or two arrives each week, adding to an already prodigious congregation. Most of these pictures have been made on the cheap, the issue of individuals not corporations, and so relegated to that furthest reach of an image market where vertical integration, hardball monopolies and a crushing capital accumulation ensure the ubiquitous exposure of a few movies, while relegating the rest to oblivion. For this medium, which takes time itself as one of its materials, there is the Big Time, and no time at all. There is no middle class of exposure.

Operating as a distributor, a mediatheque and resource and education centre with an emphasis on the contemporary media arts, Vtape’s mandate is to serve both artists and audiences by assisting and encouraging the appreciation, pedagogy, preservation, restoration and understanding of media works by artists and independents…To support the study of contemporary media arts, Vtape provides an extensive on-site resource centre for students, researchers and instructors, including articles, catalogues, artists’ files and tapes for viewing.

Since 1994, Vtape has been in a working partnership with AFVAA (Aboriginal Film & Video Art Alliance, Ontario) to encourage distribution of Aboriginally produced video and film. Since 1996, Vtape published two catalogues of Aboriginally produced film and video, most recently imagineNATIVE. Over the last year, a series of promotional workshops and screenings of Aboriginally produced works are being presented throughout Ontario…

In order to stimulate the exhibition of video and media art, Vtape continues to present artist’s talks, workshops and curated exhibitions of independent video on-site and at invited venues. As well, a strategic set of support services have been developed for arts centres, galleries, curators and individual artists to facilitate and enhance the exhibition of the media arts locally and nationally, including providing cost-effective exhibition and projection equipment for media artworks.Vtape Mandate/Mission

They called it “art,” “video art,” but let’s be frank, for many years there was little to separate these non-denominational items from the after-school special, the low rent TV doc, dramas made with friends in place of actors. And then there is “documentation,” which is neither art, nor quite not art either. It is the residue, the thing left behind after the art (usually a performance, an action) has happened. Generally unedited, shot from a distance with an unchanging frame, these “real time” stares are a reasonable substitute for locking yourself up in a Zen monastery, or volunteering for solitary confinement. Not that extreme viewer fatigue was the exclusive preserve of video art by any means, but it wore the suspicions of every newcomer. Besides, dull paintings could be passed over in a glance, video required time for even for its harshest critics to say no.

Video was first a small medium. A medium of detail, of proximity, of immediacy, and above all, of individual reclamation. A camera that jots things down. An eye that mulls things over. Smallness was never adversity. Jan Peacock

The monitoring of these faint heartbeats, the steady massage ensuring that circulation would not stop entirely, became the task of Kim and Lisa. They would hold their hope up in the face of indifference, knowing somehow that it would all get better, the pool of makers larger, the work cleaner and more balanced. They thought, “The day will come when…” and then that day came, and it’s still coming. They were believers who made us believe. How could they have made this oblivion their home? Is it hope that runs through their veins?

Subject: talk talk

Date: Mon, 08 Mar 2004 03:31:14 +0100

From: mori@dds.na

To: ttx4@interlog.com

No worries about sorry, you weren’t ‘hateful’ to me, you just wanted to quit a conversation and that’s your good right. It’s not just that I think you needn’t feel too bad about things, I don’t want you to worry, so that I can feel better too. I mean, I’m aware of the selfishness of ‘caring.’ It doesn’t feel that way, but I think it works that way.

My mother also pointed to it once when I was more or less desperate about her being so desperate. I tried to solve the bad feelings by offering possible changes while she just wanted to express her desperation. Strange that I need this detour of analysis to wipe out the analytical. I want to understand what I want to forget about.

MTV is on and I hear that No Doubt (never heard of) is covering this song of Talk Talk, It’s My Life (with Madonna’s Vogue-era stylings) which has been on my mind while I’ve been making a decision about what to tell my mother (re: ‘monitoring,’ which is more a feeling than a fact, the ‘internalization of the mother’). I remember the only time my mother saw me having my own life was when I was fifteen or so. She was waiting at the back of the dance floor to take me home. I was spinning round and round in a world she never imagined. She mentioned this moment years later, recalling the dress I wore, which was from my own design. I realized then I have no idea how much she knows or wants to know.

There is a mutual greed and reserve between mothers and children, unsurprising that this leaves traces in later loves. I’m not there yet, but feel I made a little step by deciding that there is a way to banish mother from my thoughts and still be ‘faithful.’ Still searching for better versions of loyalty or obedience.

You’re seeing the doctor tomorrow. I hope it adds something to clarity, and if not, to something else. Enough of talk now, I kiss kiss I stroke stroke you.

It’s fall 2001 and I’m in Kingston, home of the penitentiary and the university, two months after the World Trade Centre went down. The cost of empires loom over everything here. I’m in Kingston because they asked, Susan Lord and Gary Kibbins, for three days my new parents, and I’ve learned this lesson well enough. When they offer, you say yes. Yes mother. Yes father. I’m grateful to be leaving my apartment, my small thoughts, behind, and besides, these parents are whip smart and kind and gracious. How could I keep my secrets from them? My nervousness about performing myself prevents me from hearing much of the proceedings, a conference on ‘experimentalism.’ Most of it drifts by in a blur. Steve Reinke (was it Steve?) said that all Canadian artists are either bureaucrats or educators. (Or was that AA Bronson?). Andy Patterson sang a beautiful, hilarious, very touching song in a bar. Lisa cried.

To act is to share in the community of actions… Susan Sontag

What I remember most of all is her stammered beginning, the determination to go on after she broke down the first time. After all the witty, perfect, flashing papers had been delivered, she couldn’t keep the feeling from overtaking her, and didn’t make it in the end, folded her face back into her hands and let Richard Fung, the stalwart, the one who never says no, carry on in her place. What struck me right away is that these tears were not weakness, or giving in, or any plea for pity. Not the hysterical woman, not Lisa, not ever. It was instead a moment of grieving, delivered to us, for her dear friend Colin Campbell, who was at that moment dying of cancer, which Richard knew well enough, but few of the rest of us did, and she was bringing us the news the only way she knew how, in this public offering and lament for Colin. My friend is dying, and I can’t stop from showing you what that feels like right now, right here, in front of all of you, the ones who know who him so very well, and the others, the strangers, the ones for whom Colin was just a rumour, a hardly remembered screening in a small room years ago. Remember me. Remember him. Isn’t this what it means to be an artist?

To act is to share in the community of actions recorded as images. Susan Sontag

They lit the fuse for Vtape, and then stuck around for twenty years to make sure it stayed bright. They teach together at the University of Toronto. Raised Laroux. Schemed up Tranz Tech (with others), a biennial vidfest (because, as Lisa said, she wondered where all the young people were at these fringe happenings). And made art. Videotapes by Kim and Lisa. They started back in 1983 with a piece called In the Dark. The Ontario Censor Board was front page news, closing down open screenings (because you couldn’t very well pre-view whatever hopefuls were bringing in off the street), busting A Space Gallery for showing British landscape vids which had failed to go to the Board for a thumbs up, banning movies like Pretty Baby. The Board had a mission, and the Conservative government was letting it run the clean-up act all over town. Anti-censorship rallies were part of the artist’s landscape and Kim and Lisa were in the thick of it, as usual, before deciding to weigh in to the debate with In the Dark. Taped in their bedroom, the twenty minute work shows the already undressed couple making out, touching and touching again, sharing their sex. It debuted at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art, bigged up onscreen, while they appeared live, reading texts which mused on the difference between this act, the endless skin and feel and yes of it, and its exhibition here, in public. Never mind the how many avant-garde artists will fit on a pinhead debates around erotic versus pornographic, this was home movies as agit-prop, a manifesto of intimacy, and a willingness to put themselves on the line, with their own bodies, their own Kim and Lisa-ness staked out everywhere it mattered. Not for the last time.

Lisa: “My mother was repressed and her mother before her. I’m not going to live in my mother’s house. My mother was celibate for the last years of her life. I don’t think it was by choice. She died young, she knew her place, she was a working woman, a traveling saleswoman, one of the first of her kind in North America. She knew the dangers of her job. She was careful. She was aloof, she was alone. She knew there were good girls and bad women. She chose to be a good woman who happened to drink herself to death at the age of 41…”

Kim: “I really thought the sex I saw when I was young, you know, in the magazines and in films, was the kind of sex I was going to have or at least want to have… Through my relations with women the type of sex I saw in these films and magazines seemed to be, you know, not really helpful in so far as what I was supposed to want had very little to do with what was being said to me from the people I was involved with…

Lisa: “When I started to produce my own work it was the first time in my life I felt like I was doing what I wanted. Little by little, I presented ideas about what it was to be a woman. A lot of my work from the beginning revolved around sexual identity, most of it was pretty tame stuff I thought and I went on until I went over to a friend’s house, a woman I worked with. I found a poster which I’d made for a video taped up on her refrigerator. The poster was a picture of me, naked, holding a gun and an inscription on it about being a lady killer. This poster taped up on her fridge had a target drawn on my stomach, she told me her husband had done it. She told me he said, “That’s what she’s asking for, isn’t it?” I don’t remember what I thought was weirder, that he had done it or that she had left it up there, or that the target was on my stomach and not on my heart…”

Kim: “…Pornography has been produced in a way that reinforces dominance along gender lines. I can’t just disagree and leave it at that, you know, and I’m not threatened in a physical way the same way women are, by the violence in porn. At the same time, I’m against censorship and I’m pro sex in a political sense, and I guess if we don’t produce positive depictions of sexuality then this discussion just can’t include me.”

Lisa: “When I saw this tape tonight I’m not sorry we produced it. I know it’s not correct in the way you always want your work to be, it’s not perfect. It doesn’t say all the things we wanted it to. When we were having the sex we recorded it was for me, but showing it publicly is different. I think that’s more for my mother and daughter.”

I was working at Canadian Filmmakers then, like Vtape, it is a small-time distributor dedicated to fringe media, and my co-worker Helen, a once librarian, arrived one morning flushed with news from Boston’s ICA. “I’ve just seen In the Dark, and it was so warming. You really should have been there,” she told me, though she was shaking her head while she said it, wondering how they managed the nerve, to show yourself like that, and in front of your friends. “But they can get away with it,” she added, with that old world maternal smile, part whimsical regret, part pride (we were all her children then), “because they’re so beautiful.”

The gestures of love and the gestures of work. The private place, the one that belongs to the two of you alone, that somehow creates you as a couple. The codes of touch and speech, the moments of opening and closing, all this was somehow on display. A community of images. An orgy of pictures. A simple enough entreaty. Join us.

“Afterwards no one said a word, I mean, what were you going to say after all that?” I nodded, understanding too well how the body silences. I had been diagnosed with the HIV virus and hadn’t told Helen about it, or anyone else I didn’t absolutely have to. Each admission seemed another place this illness could sink its hooks into me. Ridiculous of course, this wasn’t a strategy but a full on rush into fear. Old friend and companion. The image that appears when the last movie is over.

Subject: talk talk

Date: Wed, 10 Mar 2004 05:11:23 +0300

From: ttx4@interlog.com

To: mori@dds.na

Unplugged the phone for the weekend, couldn’t bear another shameful scene, need to shut down and take stock. Work. Thanks for the message you left, the Clario piano so touching, it’s what I need now. The words seem so pointless, especially prospects of a cure. It’s my mother but also what I’ve turned my mother into. The association of her with the voice inside, infinitely demanding voice, that is busy making to-do lists, always hungry for more. First the voice, and then the rage which is aimed at her alright, but also everything that looks like her, the audience for my movies for instance, and you and I first of all. It’s the inability to take those places which she showed me could be loved, and really love them. Ridiculous to be dragging you into all this, not because of who you are, or how I feel about you, but exactly because of our distance. These are not really matters which can be conducted across the Atlantic, so in place of what needs to take place there is only worry and phone bills. Still feel it would be much better for you to find some handsome Amsterdamer and be easy together. Won’t be using the phone to talk to you or anyone else for a while, I think you can imagine how horrifying it is to have no idea what will come out of one’s mouth. Possession must feel the same.

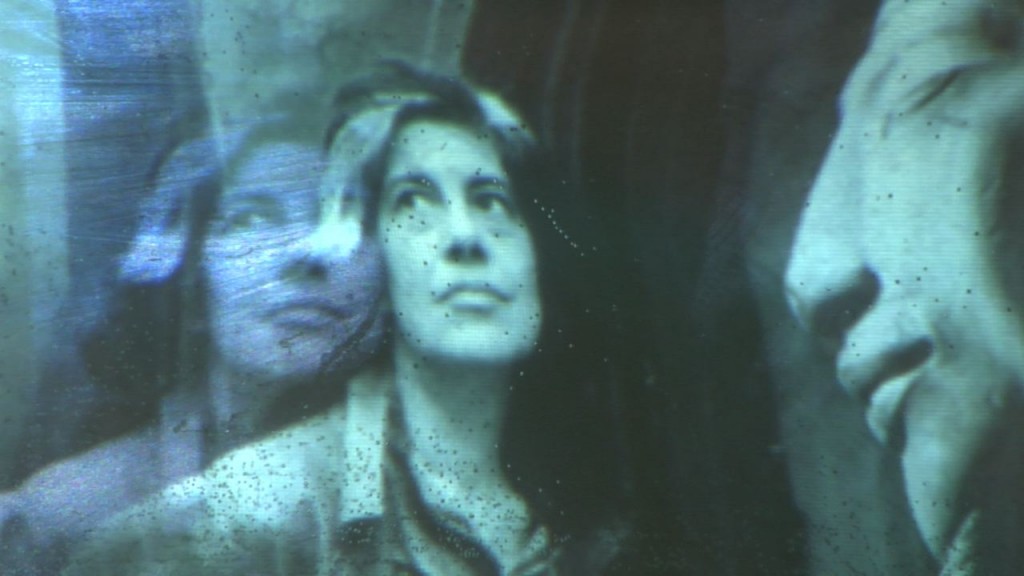

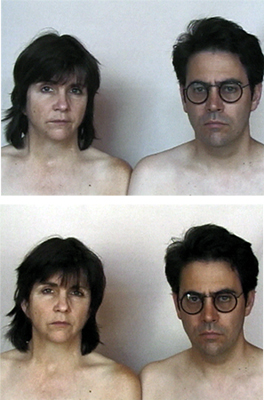

We’re Getting Younger All The Time (20 minutes 2000) is a looping, single channel video installation which shows, who else, Kim and Lisa staring into the lens, head and shoulder, side by each. They had set themselves this task: to stand for twenty minutes each hour, for twelve hours, and when they were through they sped it all up and ran the hourly chunks backwards. See, we’re getting younger! Sure, the title is ironic. In place of the nubile frolics of In the Dark we are confronted with a middle-aged version, they’re still beautiful, you understand, but not in that ready-for-my-MTV-close-up kind of way. And worse, with the enhanced resolution of video, the marks are clearer than ever, the grim line across his forehead, the years tugging at the corners of her mouth. This movie looks back in answer to their first work, it is the reaction shot, made seventeen years later, no surprise it is not happiness jumping all over their faces. But wait, wait, don’t take my word for it, have a look for yourself, what do you think?

Enduring. That’s the word that comes to my mind when I look at these pictures. They are going through it, taking it, enduring the way they always have. Looking straight ahead, touching shoulders, naked.

And now what? That’s the question that comes to me when I look at these pictures. They present themselves as evidence, proof of a journey together, offering us the frame they have put around this trip. The frame of the two of them.

Here we are now. Look. And look at us looking. The rest of us are spectators, walking in and out of the room of the installation, watching the two of them up onscreen, or at the other folks who have chanced in from the rain. Our look is free to choose. But always they are staring straight ahead, only apparently ‘at’ us, but in reality into the machine that reproduces them, the camera they walk to Little Italy to make this conceptual home movie. Their look is not free because it is attached to an idea, the idea of video perhaps, which had promised so much, which had delivered more than even they could hope for, but it’s been a long day, it’s been a long weekend, a long life. How much further? Do we have to? No, perhaps not that. Never doubt, not when there’s such a long get-to list still on the desktop. Better organize that next conference, sponsor another visiting artist, commission more installations. Not obligation, no, that would imply punishment, resentment, heirarchy. Or is it that I don’t want to imagine their obligation, to make it my own, to get off my couch and pitch in. How long do we have to stand here? That’s the question that comes to me when I look at these pictures. And I can’t help wondering: Is that why they look so tired?

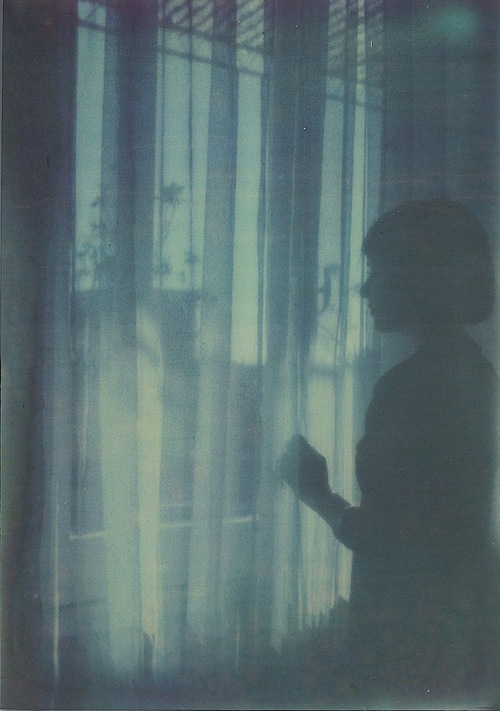

We’re Getting Younger is the first of a trio of installations. They’re still working on the last one, projected to be over an hour. Kim tells me that they’re almost ready to plunge in. “I can always tell when it’s time,” he says, “because we both start saying the same thing to each other.” The second gesture is a three minute DVD loop called Practicing Death. It shows the sleeping faces of Kim, then Lisa, in a silvery solarization, their faces matted up with a mottled wall behind. A steady chain of dissolves link the two head shots as a white text scrolls across the screen. No sounds here and no need for them. It’s all up there between the four corners.

Their thoughts are a sound we can’t hear. …this night…or the one before? No, this night. You were afraid… the whole of time is one single night. You were afraid to look more closely… the time I was inside… of it… or not it? It. The cracking of the cage. … didn’t make a sound. …nothing? …dreamless, soundless. Were you afraid?

Here is the long night of the couple, the insistent dissolves erasing the authorship of thought (is it his? hers?) producing a dialogue of one. Dreamy, but not in some other worldly way, nothing strange on strange, but instead a documentary of the unconscious. My fear is your fear. This moment, I mean, our time together, is a long time. Is time the cage, or each other? Will we manage to make it through this night together, knowing there’s no end to it? Their eyes are closed, their faces still, occasionally trembling, suggesting movement, but mostly it is the material which moves, marrying them, dissolving the space between the two, while managing always to acknowledge the cost, the trial of presentation. Of you and I together.

Subject: talk talk

Date: Sat, 13 Mar 2004 01:45:11 +0500

From: mori@dds.na

To: ttx4@interlog.com

I couldn’t write it down, not even to myself. The only lines I wrote were: “I had a dream about my mother. I can’t write it down.”

It made me aware of the ‘taboo.’ If I had dreamt that she had tried to kill me, the dream might have been a nightmare, and the feelings afterwards extremely painful, but I would not have felt the same shame to write it down.

What is important to know, or to say, for me, is that I was passive, not really resisting, but feeling: this isn’t right. How can I tell her and not offend her, in this, the only pleasure she has? As her fingers slipped into me from behind, she whispered: “This is new to me.” I don’t know anymore what I was feeling, it hadn’t so much to do with what is right or wrong, but I just didn’t like it, and besides, we were among people, I worried they were looking, plus I wondered where she so all of a sudden got the energy to move this way. I left the room, searching for someone I didn’t find, and when I came back she was gone. I found her asleep in another room. I apologized for leaving, and she gave me the smile of someone who had just discovered something. There was no shame or regret on her side and I didn’t feel angry but everything had changed.

Waking up I felt shocked, how could I ever talk to my mother again? It didn’t feel disgusting or bad, but deeply unwanted. Not painful or cruel but… I don’t know how to put it, not the mirror of desire but beyond desire.

“How are you doing?” In Toronto, greeting is a verb, what are you doing, already the measuring sticks are out in this metropolis of work, a city built up over the watershed, working so we don’t notice the leakage. Sofar as the art world goes, that archipelago of converted shops and government sponsored festivals, the small turning centre of this microverse is 401 Richmond Street, a handsome four floor warehouse just south of Chinatown which hosts galleries and distributors, new media and painting, feminist collectives, old fests and new. I worked there for a year and found the social pressures punishing. The deadline fever runs through those halls in a steady drip of panic, along with the requirement to handle a bevy of life changing encounters which might happen on a trip to the toilet, or walking out for a smoke. And unlike the festival I worked for, Kim and Lisa are chugging it out in a distribution joint, an office that actually invites people to drop in all the time. They’re running video installations in the sideroom, with a tape library that sees students, curators and artists bigging up on the next flash. I don’t know how they do it, all those names, all that need, and of course with any distributor there are the hopes of career and ambition. Will you show my work to the serious one from Dokumenta? The honcho from the Brazil museum? Who is in, and who is out, aren’t these decisions being made here, isn’t this a likely place for a fantastical resentment, that lingering feel common to all artists that the warm glows of attention are neither regular nor large enough? Those row upon rows of tapes up on the shelves each represent a desire for visibility, an unquenchable appetite that not even the most diligent public servants could fulfill. So why no rising backlash, no angry demands for change when it comes to Vtape? It should be admitted that expectations have always been on the low side for those born to the raster, at least until the Turner Prize, and those mega-projections which grace the walls of our museums like the history paintings of a few centuries back. But the stars don’t come looking for their shot at Vtape, not mostly anyways, it’s the once students, first timers, or those with no other place to go. Even so you’d think they… But they never do. You don’t hear it in whispers even, instead a helpless shrug, a rolling of eyes. It’s Kim and Lisa, what are you gonna do, get pissed?

Two people attentive to a detail of the world make a society, and the object they find significant has crossed over from meaninglessness to symbol. Art is always the replacing of indifference by attention. Guy Davenport

Kim and Lisa don’t go out looking for a drink to talk through. They’re not dressing for the occasion, they are the occasion. That’s the feeling I get when I see them in the kitchen, the living room, the office. Everywhere there is continuity, there’s no line, or at least less of one, between private dreams and public ones. I’ve watched some of my older friends disappear into the black hole of their families, no time for chitchat, they’re locked away in their houses. Glassed up in their cars. Busy. They are a forcefield of busy. It hooks them into new worlds sure enough, the daycare and special schools, landlordism and the jobs that permit them the luxury of first world children. The vortex of their lives keeps them from others in the city, the tribe, former friends. They’ve thrown up the ramparts, battened down the hatches of family, never mind the outside world, they’re just trying to get by. I think they’re not alone in this, it seems the usual thing, this suburbia inside the city. The circulation and visibility that is the heart of every metropolitan culture is arrested in the figure of the couple (“Yeah, I don’t see X around much anymore. Not since he met… Not since she met…) We are disappearing into our loves, our private selves, our moats of money and self interest. For every I do, there are a hundred I don’ts. I don’t go to that bar anymore. That coffee shop. That friend. I don’t. I don’t. I don’t. They call us to witness, to celebrate the union, and then they disappear. Not everyone or every time, but there is gravity at work, natural laws. The suburbs promise safety first of all. A life at one remove from the city, and the unknown. A flight from risk, and the necessity of having to stage oneself outside home and work, where the roles are already waiting.

I remember seeing Kim and Lisa in the fall. I got back into town just long enough to catch the very last show of Tranz Tech. Where else would they be? It was a night of music as it turned out, whose performers were so retiring one sat in the dark and listened to his CD, while another was so thoroughly masked by stage props we couldn’t make them out at all. Nice tunes though. When it was finished, and the last drink from the last cup lay dripping from the garbage cans, I walked out and found them there, Kim and Lisa, bent down on the floor unplugging cables. “Just have to get these back to Vtape,” Kim smiled at me. Kim is the master of positive cognitive thinking. I’ve never heard anyone talk like Kim before. He has turned optimism into a discipline, which he practices daily, with everyone around him, the cultural poobahs, and the stragglers who wander in off the street. In the midst of catastrophe he will let us know that it’s possible to go on. Not with our heads on the floor, but staring straight ahead, looking, really looking at it. Past the catastrophe of the couple, the old families, the solitary artists, and right on into the new hopes that they have been busy living and building and making a place for all of us. What are you waiting for? C’mon inside, there’s room for everyone.

Notes on Becoming… (June 2010)

For the past eight years I have started awake each morning with the sound of Toronto construction. Several thousand new neighbours now look out from balconies or jog past my windows on their way to a better future. And still the jackhammers shudder on, opening the ground so that 50,000 newer residents can warm themselves in a downtown that is busy shape shifting into someone’s dream of a city.

After shooting her epic home movie Kitch’s Last Meal (super-8 film, double projection, 1973-1976), Carolee Schneemann remarked that everything she filmed died or disappeared. She had laid down this simple rule: she would keep filming until her darling cat Kitch died, which was surely any day now, Kitch could hardly make her way across the floor at feeding time. But somehow under Carolee’s renewed attentions, Kitch found a second breath, and lived for several more years as the artist applied her lens to a neighborhood where buildings were busy disappearing, or a relationship that was ending, or dying friends. She became convinced that Kitsch was the lone undead moment of her world, and that everything else on record was doomed.

I remember reading her remarks with a sense of dread, feeling my small collection of seeing prosthetics as weapons of minor destruction, voodoo technologies. For several years, raising a camera felt like putting a hit on whatever was in the viewfinder, and I stopped making pictures entirely, preferring instead to work with other people’s bad juju. Eventually I realized that if Carolee’s insight was true, it was not because a camera had been raised, but because everything around us was busy dying, changing, remaking itself. What relief. I could begin making pictures again.

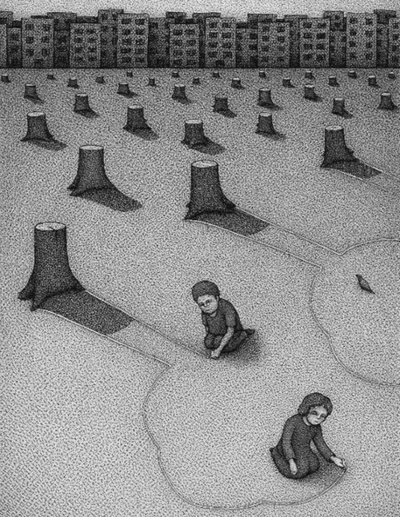

Becoming… (2010) is the latest installation from Lisa Steele and Kim Tomczak, soon to be gracing three walls of a single large room at the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art in Toronto. They have been working on a series of city portraits featuring precisely framed architectural moments, occasionally punctuated with text screen jokes about city planners or economists. Many of their frames – largely unpeopled, the camera craned upwards – offer a meditation on past and present views of the city. Remnants of old neighborhoods and their not quite bygone dwellings nestle uneasily against a rising tide of glass and steel. The artists’ daytime vigils offer a palpable sense of loss, as if they were recording an ongoing departure, a disappearing act that each city enacts as it makes way for local versions of progress. They invite us to join them in their examination, as they search out perspectives that might make even the most familiar corners visible again.

Everyone will bring their own grooves of expectation to this architectural study, I search for signs of the yoga studios that appear newly roosting inside my city’s temporary reinvention. The traditional end of each yoga class is called savasana or corpse pose. “Practicing death, little bit each day,” as Ashtanga maestro Pattahbi Jois once remarked, means observing the winds sequentially break down the body’s four elements. The practitioner is invited to experience the rigidity of bones, the loss of fluids, a shortening of breath. The gradual loss of everything. I find this pose an excellent prep for my 50,000 new neighbours. The yoga mat is my welcome mat. The long rows of towers and the longer hopes that fill them, will remap much of what has been familiar. My favourite bookstores are already gone, the resto I lost my emotional virginity in has been leveled, the rush of beer hops sweeping off the Gardiner that signaled to my childhood self the city’s real beginning was unbricked last summer. Getting up off the mat after corpse pose I can only say yes. But what do the artists have to say about their work?

Lisa Steele: We’ve been working on the Becoming… series for several years, in four different cities to date: Vancouver, Montreal, Toronto, Berlin. It started in 2006. We had a residency in Vancouver at Video In but we didn’t know what we were going to do. We knew Vancouver really well but hadn’t been there for almost 5 years, and when we started looking around and saw all this new development, we had to ask: what happened to Vancouver? That question brought us — and our camera – out onto the street where we started to record what we were looking at. We were out almost every day for a month, just walking around, looking up, like you do when you’re getting to know a city.

Kim Tomczak: The Becoming… series is very much about the body in relation to the urban environment. Because the camera is so formally placed – each frame is locked off and static – there is a sense of the viewer stopping and looking for a long time at views that would ordinarily be passed by unnoticed. Cities are always decaying, rebuilding, being torn down, being rebuilt. Forever in a state of becoming. But becoming what?

Lisa: The framing of each sequence is very carefully selected. There has to be a dialogue between the old and the new buildings and there also had to be some proximity between these two extremes.

Kim: Maybe it’s a dysfunctional dialogue, or a disruptive dialogue. It might be subtle, angry, disguised dialogue or a mimicry. Each frame is different,

Lisa: We made rules for the recording process and applied them throughout each part of the project. For example, we don’t pan…

Kim: We don’t zoom. We find the frame and then lock off the shot. It’s seems easy – almost a cheap shot – to locate some old, broken down place and then pan to the distant skyscraper. We wanted to show the built spaces that were actually encroaching on each other in real time and in real space. Becoming… looks at the old that is not yet dead (gone) and the new that is so different, so deliberate and assertive. When they butt up against each other it creates this dialogue we’re talking about.

Mike: Many of your frames impart a sense of looming modernity. The inescapable tide of the new, with its old fashioned sense of progress and rational triumph. Older homes are dwarfed by their new neighbours, and suggest a way of life that’s passing, dated notions of community or neighbourhood.

Lisa: Internationally, there is a lot of work being done right now on the built environment. Many artists are going to extreme urban locations like Beijing, Dubai or Shanghai, making work that, frankly, can look like cultural tourism. Becoming… has a different aim. We’re interested in the extraordinary transformations of fairly ordinary cities.

Kim: We didn’t want to produce digital landscapes of the extraordinary either. There’s lots of work that uses “constructed” – digitally reconstructed, really – images of imaginary spaces, often urban spaces, that speak about what we are addressing. That’s not what the Becoming… series is about. We don’t use Photoshop – or Aftereffects or any software – to create juxtapositions; 21st century developers are doing it every day. We are just observing what is happening.

Mike: Let’s talk about the jokes. Structurally, they are presented with a certain formality – as text panels operating as inter-titles.

Kim: You’re right. They are taken from written jokes (as opposed to stand-up transcripts). We picked philosophy jokes for Berlin, economist jokes for Vancouver, and city planner jokes for Toronto. We think that the jokes encourage the viewer to use a different part of the brain for the interval between pictures. Some of the architectural images are impossible to resolve. The jokes provide a breather, so the viewer can process what has been seen and re-engage with the pictures when they re-appear.

Lisa: The jokes – like all jokes – present clichés, received ideas, about certain categories, in this case occupations. We juxtapose these with the particular characteristics of an individual city that we observe with our camera. When you’re organizing views of the city, you’re dealing with a combination of what you’ve actually seen and what the image of that city is, i.e. the stereotype, the cliché. How does a stereotype, or an image of the city, get created and circulated?

Kim: Becoming… offers a really simple switch in our position, from making a statement to looking and hearing and questioning. We needed to go out and look and listen.

Lisa: Right now, it seems like lots of people – including some artists and writers – have answers. They tell complicated stories about their art works, which have been researched for years, and the piece of writing, the video, painting or installation is the culmination of their research. Their art arrives as a solution. But we felt we didn’t have answers. For us, everything has changed. We have come out the other side, and we wonder, what happened to us? That’s what this work is about. Just asking questions.