Amateur Trash Films: an interview with Torsten Alisch

TA: The movies began for me when I was five or six, staying up to watch 50s horror movies. Seeing these giant insects started everything. When I was twenty I was drafted into the army and met a friend who was very involved with film. In the evenings we often went to an art cinema where I saw Bunuel’s Un Chien Andalou and after that I refused the army, and went into the civil service instead. A year later I found my parents’ super-8 camera. One Sunday afternoon my girlfriend and I were walking through the woods with the camera and made our first shots. We did it for fun, not to make a movie, only to shoot. Four weeks later we got back all twenty minutes from the lab and began to think about montage. That was Talking Is The Best To Remain Silent (20 minutes 1981). It’s a personal home movie about living in a small city filled with impressionistic images: foggy highways, ice in the woods, the sun going down, leaving the city in order to survive. While there’s sound, music and intertitles there’s no dialogue. When it was finished we sent it to some festivals and so it all began, though there was no idea in the beginning about being a filmmaker, just trying out a camera.

Then we began our studies in journalism, political science and history here in Berlin and decided to make a real film (still on super-8) about the history of our home town Giffhorn, and its relation with the Third Reich. It was a very normal town, and our film shows the way this normality changes into fascism. We did some interviews, found photos in the local library and used a lot of sounds from other films, including speeches from Hitler. This took two years and there wasn’t much fun in its finishing. Shortly after the film we split and I began to make movies alone. The first was called Berlin—Some Aspects Concerning Life (15 minutes 1986). It was a typical experimental city film with slow motion and fast cuts of cars which showed the city in motion. There were a lot of unfinished things and then Copy Romance (3 minutes 1986). It began with a photo of my girlfriend, we’d split and I only had this photo left of the two of us. I was working a night job at a newspaper which finished at two in the morning, but the subways didn’t start until four. One night I had this photo and went to the photocopy machine and tried to erase it, this memory, by making a copy, and then a copy of that copy and then a copy of that copy, until after 150 copies there was only one black point on the page. The film animates these pictures, beginning with a black spot which becomes the photograph, and then returning to a black spot.

The next film was nearly the same but used film footage. It’s called Motion Picture Romance (15 minutes 1990). It began with footage of the same woman walking through the streets of Berlin. I copied the film material using a super-8 projector which I rebuilt so it could freeze frames. I used subtitles and a song from a local electronic band, changing the speed of their recording and of the images, but the film is too long and I only show it for friends now.

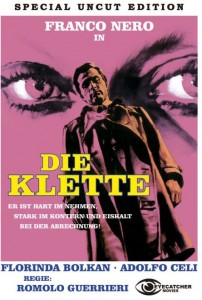

Shortly afterwards I visited the flea markets of Berlin and found condensed versions of large budget pictures in super-8. In Germany in the seventies it was very common to buy these films which cost 100 DM, but video changed all that. Now you find them in the flea market for just a few DM and I bought a lot. Often they were so badly recut you couldn’t understand the plot anymore. There was one film I watched over and over, Die Klette, an Italian criminal film made in the sixties. Eventually I uncovered a love story between Franco Nero who plays the police officer and a beautiful woman who seems to be naive but turns out to be the murderer. I refilmed the original, changing the speed and the colour from b/w to blue and red. It’s called Falsche Farben—Fake Emotions (12 minutes 1980). It focuses just on this relation between the two characters, and in this new version they’re made to repeat the same dialogue in a variety of settings. Obviously the meaning of the words shift as the scenes change.

Shortly afterwards I discovered amateur movies in the flea market and for the next five years I went every other weekend and bought 500 hours of home movies. From that time on I worked only with this material, never shooting anything myself, there was no need. Angelika (70 minutes 1994) was an episodic film which came from five hours of original material all from the same couple. Normally these amateur films are silent, you don’t understand much, but this footage all had sound. It begins in 1977 and the last material is from 1984. It shows a typical Berlin couple—there’s parties, holidays, a new cat, shopping. He films her and she him, and they often address the camera directly. For instance she’s walking on the beach saying, “Today is August 26, it’s our second day on vacation and the weather is bad. But we hope that tomorrow the sun will shine.” It seems banal, but if you keep looking you become so close. There’s a terrible sadness in their lives but they try to live happily, and it seems to work. Seems. They have this camera between them which takes the place of something they don’t have. A child? When I showed this film at first many laughed but after ten minutes they fall silent, they can’t believe what they’re seeing because it’s so intimate. Many Hollywood films try to tell stories about ordinary lives but they’re always acting in the end. This is something else.

I worked for a year on the footage. In the editing I rearranged the order, taking it out of strict chronology. I thought it was important at the film’s beginning to get certain facts straight. It was important to establish that they were a couple who were filming each other. You feel there’s a lot of disharmony between them, they drink a lot, but nothing comes out directly. You feel it sometimes, the way they look into the camera, or away from it.

ARTE is a French-German cultural channel which decided to devote an evening to daily soap operas, and wanted to use Angelika as part of the evening, split into parts and shown throughout the night. The problem was that TV wanted to have the copyright so I had to find this couple: Dieter and Angelika. Often if you sent films to Kodak they were lost so they encouraged amateurs to film their address at the beginning of the roll. One of their rolls had an address, and I looked it up but they didn’t live there anymore. So I looked in the telephone book, found ten listings and began to call. As soon as I made the third call and heard the answer I knew it was her. Her voice was so familiar to me. So I met them. I told them I’d found their material and that TV was interested but they were only interested in the money. They were both very poor. She’d left him, and he stayed on in the apartment but couldn’t afford the rent, so it was repossessed with all of their belongings. Everything, the furniture, their clothes, the home movies were sold to a flea market. They left it all behind, wanting to start a new life. In the end they asked for a copy of the TV show but not the original material, they just weren’t that interested in their history. They only speak to each other through lawyers now.

MH: How do you distribute your work?

TA: In 1990 Dagie Brundert, Dirk Baranek and I formed Jochen Enterprises. Jochen is one of the most common names in Germany. We tried to distribute super-8 movies of our own and others, organizing tours through Germany. We made fanzines for several film festivals like the short film fest in Hamburg, Interfilm fest in Berlin. By publishing this fanzine we became interested in comics, made comics and now we are the biggest independent comic publisher in Germany.

MH: Festivals seem the most important way for work to be seen in Europe.

TA: Some small festivals are important because they show work you can’t see in Osnabruck or Lucerne. There’s another level of filmers from little towns who don’t know much about the experimental film scene, they only hear there’s a fest in the next city, and if you don’t go you’ll never see this work again. Osnabruck and Lucerne are the most famous festivals, they’re the establishment of the experimental film scene. They’re very focused on art, and it’s not that I hate it, I’m just not that interested in these films. I love trashy, amateur films, and for those I have to go somewhere else.

Once a year we (Jochen Enterprises) show our favorite films in the Open Air Cinema in Berlin at Hasenheide. There’s 1000 seats and every year it’s sold out. It’s one evening. We tried to organize tours and screenings in cinemas and there were ten or twenty people, but now we believe it’s better to make a kind of happening, just once a year, and many people come. We love it and don’t want to organize any more tours through Germany. With this screening they don’t know the expression ‘experimental film,’ they just want to have an interesting evening. Often they’re a little confused, but they come again and again.

In Hamburg there’s an important group called War Nichts Machts Nichts (It wasn’t good but it’s not so important). Every month they organize a short film evening for which they make their own films and invite others. This couple are the only group in Germany today that regularly shows short experimental work on a regular basis. The cinema is called Lichtmess (Lightmass). It’s a Christian expression, meaning the coming of the light. And people come. The only open air festival left in Germany is in a little town near Frankfurt called Weiterstadt. It’s five evenings long, and there’s about 1000 people watching short experimental trash films in a small wood, and it’s a happening. Many local people come to watch, not experimental directors from the United States. It’s a crazy festival in a crazy little town.

MH: What about your own filmwork?

TA: I made ten more films from this amateur found footage material, most around three minutes long. All ten are single uncut rolls with an accompanying song. And then I did The Lost Charm of the Kodak Life (15 minutes 1993). It’s a compilation of the most incredible and beautiful scenes I found in these 5000 hours of footage. For example there’s a personal experimental film from the GDR made in 1968 shortly after Czechoslovakia was invaded. In East Germany there was a kid’s TV program called The Sandman, and the filmmaker animated a puppet of the Sandman walking to Prague mixed with these flower power images from his garden. That was my last film, after that I didn’t finish things anymore. I felt this found footage thing is finished for me. I don’t know what kind of films lie in the future, maybe working with computers but I don’t know. I don’t want to make big movies, I’m only interested in the self made way, where you pay for what you do yourself. You don’t need funds from other people.

Originally published in: Millennium Film Journal Nos. 30/31 (Fall 1997)