Listening: an interview with Valerie Tereszko

Born and raised on Canada’s west coast, Valerie Tereszko hosts a condition which makes her unique amongst Canada’s film artists, she is deaf. But far from embracing a cinema of silence, Tereszko has begun to articulate a radically personal and subjective sound work. Often employing technical means to mime the eccentricities of her own hearing, Tereszko successfully induces in her audience her own experience of sound. Claiming her project is “doing for the ears what Brakhage has done for the eyes,” Tereszko’s blend of dramatized sequences, autobiography and a carefully crafted passion gather in a chorus that is at once personal and political.

VT: I’ve been fascinated by film since I was twelve years old. I used to watch stars like Betty Davis, Joan Crawford and Katherine Hepburn over and over and imitate their parts at home. I had trouble understanding them at first, so I went until I got it, often three times or more. They helped me to lip read, and taught me how to communicate socially. Learning to speak a language is one thing, but learning to communicate on a social level is another. Movies and television were tools I’ve used since I was a kid. When I grew up people around me got tired of repeating the same words, and I felt guilty. But movies I could listen to over and over and they never minded. When I was fourteen I couldn’t hear a telephone, TV or a movie. But a woman from California came with a program called Auralism, which teaches the hearing impaired to hear a little. I was on this program and now I can talk on the phone and hear movie soundtracks. It was a long learning process, I don’t hear everything, but I understand the language better and learned to predict what people will say. Language is really very predictable unless you’re talking philosophy.

MH: Is language predictable or the people using it?

VT: People are repeating the same thing all the time. Hi, how are you? Should we meet here? I have no hearing in one ear, and with the other I don’t hear any consonants, only vowels. I’ve been trained to fill in the rest. My mother and I practiced every day for half an hour on the telephone so I’d be able to use the phone. At first I didn’t hear anything at all, then by twenty-one I could talk for five minutes, and it wasn’t until I was thirty that I was able to carry on a phone conversation. Learning how to do sound recording in the editing room and using the Nagra tape recorder made me understand more about language and sound. Sound needs to be made visual for me before I can recognize it acoustically. A musician friend bought an Apple computer which he used to make beautiful sounds. I said, ‘Wow what was that?’ And he said, ‘A cricket.’ I’ve always wondered what a cricket sounded like, I’ve asked people to imitate the sound of a cricket, but now with powerful amplifiers the cricket was there. This was the first time I heard a cricket, when I was thirty one. Both my parents are musicians so I was interested in music very early. I would wait for everyone to leave so I could play the piano everyday just to feel the vibrations. I don’t agree that the education of the deaf should lack music. You don’t need to hear in order to understand music and language. The piano is very visual. When I buy a record I have to get the words on paper in order to hear them, I hear the voice, I hear the music, but what is the content? I buy a songbook, then I train myself to sing the song. When I was young it would take six months to learn a song, I would play a record over and over again until I’d get it. Now I’m able to get it in one week because I’m trained in psychoacoustics. Everybody has a response to sound, some people may dislike a sound because it triggers a childhood memory. Many don’t like the sound of high heeled shoes. Some like the sound of dogs barking, others don’t. Why? It doesn’t have anything to do with how much hearing you have, but the personality of your hearing.

MH: Do you think memory can be based on sound and not language? Usually the events in my past are like a story I return to, a text that begins with my own naming. But you’re suggesting that a succession of room tones holds a shape that implicates our personality.

VT: Most people don’t remember because they’re not trained, they don’t pay attention. But the hearing impaired have lived in sound technology since birth and find it fascinating. What do the hearing people hear? What do I hear?

I came to Vancouver in the early 1980’s without plans, for me the movies were a childhood fantasy. I was taking courses in photography but wasn’t satisfied, there was something missing. I talked about it with my neighbor Marek, who was going to film school. He was the one who said film’s for you and that woke me up. I quit photography and enrolled in Simon Fraser University. Al Razutis, Kaja Silverman and Michael Elliot Hurst were teaching there, so it was a very strong political era. I schooled from 1983-87. The first film I made was Where Are the Clowns? (3 minutes 3-screen 1984), a short film made on three screens. It’s like a signature, an autograph. It’s about a man who wants to be a clown but couldn’t because he was so poor. Now he’s an old man. He can’t get welfare because he doesn’t have an address. He goes to McDonald’s and takes packages of mustard and ketchup and gets some flour and dirt and uses it to turn himself into a clown. He makes himself up in front of a shattered mirror. I used a Bolex camera which was rewound five times to show five faces in the glass. All the while Judy Collins’s song Where are the Clowns? is playing, but as he finishes the make-up, the mirror and the music break apart together. He moves to the window where he sees a young clown playing with a swan he makes out of his hand, like the old shadow plays. Using a rear screen projector, I created three irregularly spaced frames within a frame, so as he looks out he sees three young clowns. This effect is repeated on all three screens. Depressed, the old man pulls his make-up off at the end. There’s a lot of hope and despair together. The song was the source, but in the end you don’t need the music anymore because it’s in the image. I presented it on three screens—one above the other two, all of them irregularly spaced. I don’t like strict verticals and horizontals, I wanted to break down the frame so I used superimposition, and broke the frame’s containment by multiplying them.

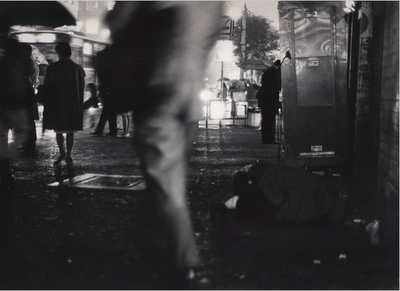

The next film that’s really mine is called Human on My Faithless Arm (20 minutes 1987). In order to get into fourth year film school we had to arrive with a script, but this wasn’t the script for Human, I felt I wasn’t ready to make that yet. I was worried about damaging the woman’s reputation, that I wasn’t mature enough, that I had to learn more about life before I could make it. I felt very vulnerable and afraid. But when I handed this other script into Al Razutis he said no (laughs), you should make Human instead. We had a long talk about it, and finally I said okay. Human on my Faithless Arm is about a woman who lives here in Vancouver. She’s a lesbian and her welfare workers took her baby away because she was living with another woman. They told her she had to make a choice between her sexuality and her child. I’d known this woman for four years already, at first we saw each other once in a while, but for the last two years we were together every weekend, playing pool and smoking and eating chocolate bars. She quit school after grade four and lived on the streets. I wanted to dramatize this so I dressed up as a street kid and hung around the streets. I wore greasy hair, tight jeans, smoked, and listened to them speaking. Then I was ready to write the script.

The opening shot pans over a clothesline and follows a woman walking in front of a wall. It’s a powerful metaphor for sexuality, showing the feminine and masculine, the soft clothing and hard wall. The wall is in color but the woman is in black and white. When you look at urban planning today, we are always renovating the front doors of our buildings, but never the back door. The back door is only for the garbage man. Our back walls and alleys have never been painted, yet they’re accepted, but the front door has to be painted in order to be accepted. So the walls which have been painted are in color, they’re accepted, but the woman who walks in front of them in black and white, is not. I used six film strips printed together to make this scene, to emphasize the difference between foreground and background.

MH: She appears doubled, her negative and positive images printed together slightly out of register. Why is that?

VT: The black shadow that comes out of her is a metaphor for the sexuality she can’t accept. If there’s something we dislike in ourselves we attack it. She wishes she was sexually conventional because her child is being taken away from her. She’s been taught to hate the difference she represents.

MH: Her maternal feelings for her child seem very conventional. She says, “I love my daughter. She wants candy, I give her candy. I want to give her clothes.” Little else about her seems conventional but this bond between mother and daughter, yet this bond motivates a lot of what she does.

VT: There’s a myth that says if you’re gay you won’t like children, or you shouldn’t have them because you’ll raise them to be gay as well. This is what the welfare department is saying to her, but it’s not true at all.

MH: It’s weird that we remain so fixated on the classical cultures of Greece and Rome—they’re very important for our understanding of ourselves. Parts of these cultures explicitly celebrated gay relations, Plato, amongst others who are consistently read, wrote about it at length, yet this hasn’t seemed to dim much of the homophobia we’re still living in. There’s been a line drawn between culture and sexuality—the waistline perhaps, or the reason we still have to make slogans about reason over passion in this country. The actress in your film speaks in a very emphatic manner throughout—she performs her sign language as she talks, not so much speaking her words as having them wrenched out of her. I’ve always felt hers to be one of the great performances in fringe cinema.

VT: Sign language is like handwriting, each one is different. We have a tonality in our voice that gives expression to our emotions. In sign language gesture expresses mood. If this woman is angry, her sign language is very heavy, her hands clenched and tight. I was trying to break down cinematic language by inserting the rhythm of American sign language into the film. I wanted to follow the sharpness of this language in the film’s editing. Sign language is very blunt compared to spoken language.

MH: Why is it blunt?

VT: In the American sign language there are no words for ‘in’ ‘a’ ‘the’, no tenses, no ‘when I was going,’ ‘I went,’ ‘I would have gone.’ This is all represented by ‘I go’ and the gesture suggests its tense. The body expresses the softness of the emotion or the anger, as well as the time of the action. You have to act out the language, like a pantomime. I think most hearing impaired people are good actors (laughs).

The actor’s language is simple and crude because this character hasn’t had a lot of formal training. Some of the hearing impaired have a university level of language vocabulary, others have high school equivalents, others have grade four. Some don’t communicate well with sign language, others have achieved an intellectual level. The hearing impaired in America have a higher level of sign language than Canadians because the government spends more money there. In Vancouver the average reading level is grade four. Every school is different. There are two traditional philosophies of education: Oralism (talking) and Manualism (sign language). Sign language hasn’t been recognized as a language here because of its roots in French syntax. This split between sign language and speaking replays the political tensions between French and English. Our language is also the language of politics, the language that’s permitted. I never learned ASL (American Sign Language), my parents sent me to a school in Minneapolis where I learned to lip read.

After the woman has finished speaking about her daughter and the welfare workers the next scene is very different.

MH: Her monologue is followed by another dramatic sequence, an unannounced flashback of the woman’s life as a teenager. It shows three kids on the street. The one drinking has lifted some money from his folks and wants to go to the liquor store and buy more. The couple are deciding what to do, but they’re all drifting.

VT: When you’re a street kid, time, life, money doesn’t mean anything. Most are tormented by lack of love, and when you feel unloved, every minute is the same minute. I wanted to show different parts of her life, like a journey through a kaleidoscope. In many of the film’s scenes she’s a different age, though often you don’t see her at all. For instance this scene is shot entirely from her point of view, and the audio is subjective as well, it sounds like a hearing impaired person listening. When the subject is speaking with their back to the camera then we can’t lip read anymore so the sound is muffled. There’s so many things preventing us from hearing-like a person with a heavy beard or mustache, a person who keeps looking away from you, a mumbler, or a woman with a very soft voice. When they turn back to the camera we can lip read again, and the sound is restored. I removed all the consonants from this scene so that the audience would know what it’s like to be hearing impaired. If you don’t hear what’s going on you feel rejected. Half the audience understands this I think, the other half just thinks it’s a very bad recording (laughs).

MH: After the three kids talking out on the street the screen fills with water, the never-say-die image of Vancouver films.

VT: Water is a natural amplifier of sound. I use water a lot in order to hear music, I take my music in my bathroom, the water creates echoes of the music so I can hear it. I included the water because it’s beautiful. It helps the audience prepare for the difficult poem that’s to come. It’s like a rest, a pause.

MH: The notion of a rest is common in music but unusual in film.

VT: There’s different kinds of languages explored in the film and different ways of hearing these languages. After the water there’s a poem read on the soundtrack called Lullaby by W.H. Auden. Like the classical poets, Auden was fascinated with sound and the rhythm of language. When he wrote Lullaby he was an old man already, writing about his young male lover of seventeen. He knew their love wasn’t true, that the feelings between the two men weren’t real. Auden knew that the young boy was using him because he was a famous writer, and that he was denying his age by being with someone so young. This is what the poem’s about. Why did I put it in the film? Because the woman has to choose between staying with her lover which is being true, or becoming straight so she can keep her child. In his writing of the poem Auden never used ‘he’ or ‘she’ it’s always ‘human.’ He didn’t let anyone know he was gay until he was in his eighties, he was hiding in the closet all those years.

MH: The film’s title comes from Auden’s poem. What does ‘human on my faithless arm’ mean?

VT: His lover is in his arms, but his arm is faithless because he’s only pretending to love. I shot the sequence in a room where the only light came from flashlights tied to my arms. I recited the poem with my hands, in the Art Sign Language, so you could say that this sequence is in ‘sync,’ though few will recognize it. From this footage I isolated a series of frames which I froze on the optical printer to spell out the poem.

MH: There’s a match cut between one of these abstract figures in darkness and a woman turning about a pole. This scene returns to the characters we saw earlier out on the street, only this time the talk isn’t about alcohol but drugs. It’s filled with motifs of repetition and circularity. The woman keeps turning about the pole, another repeats a name, and the guy keeps asking the same questions over and over. What is he asking?

VT: I was thinking of how difficult it is to lip read in the dark. At night someone asks for a dime, only you don’t know what they’re saying. Are they asking for a dime? Are they saying nasty things to you? You don’t know. You can ignore it because you can hear it. But we need to lip read, and if we look at the person we’re encouraging danger. Much of the sound in this alley scene is distorted so you don’t know what they’re saying. And when people are on drugs you can’t lip read them at all. I had the woman swing around the pole because I saw a guy doing it on the street early one morning. I was there with my cameraman and we watched him going around for twenty minutes. So we asked the woman actor to do it. The guy in the scene knew what it was like to be on drugs, he’s lived in that lifestyle before, so we gave him some lines and let him improvise and he did very well. The second woman repeats a woman’s name over and over again, like a lost soul. These people have no family, no love, nothing.

MH: They all appear trapped in histories they’re doomed to repeat, like needles at the end of their vinyl. But nobody has the same record, they just happen to be in the same place, all tuning out at the same time.

VT: My film focuses on the internal, like Brakhage’s work with eyesight, only with sound. When I think about the film’s making, it’s like walking through a gallery. One scene follows the next without flowing into each other. Each scene has a different color. The woman going around the pole is making a strange noise, she’s crying out for methadone, methadone. The audiologist scene which follows also has a great deal of repetition on the soundtrack. A man asks, “Can you hear this sound? Can you hear this sound?” We see a hearing impaired person being tested to gauge the extent of their hearing loss. We have to go every four years to get our hearing tested, in order to replace our hearing aid. They ask that you push buttons if you can hear the sound. I don’t mind going to the room, for me it’s something to play with. But others don’t like it, including the women in the film, she feels manipulated by the audiologist. Instead of being able to respond to the test she hears fragments of her past, moments in her struggle to listen. When I showed the film to my audiologist she found it very educational because she’d never understood why people don’t enjoy the process. Now she’s going to show it to other audiologists.

MH: It’s very oppressive. The single, unchanging shot of the room photographed with a wide angle lens bends all the walls out of shape. And as a viewer of the film I’m not prepared in a narrative way for the space I’m encountering. I’m just thrown across a piece of splicing tape into a different part of her history. I don’t know why this man is telling her, “Press the button after the tone.” Understanding comes slowly, along with the oppressive feel of an institution at work. The insistent repetition of the man’s orders are counterbalanced with the woman’s intensely subjective recollections, yet both feature a great deal of repetition, one of a corporate order, the other personal.

VT: Repetition is what we remember, it is memory. It takes the hearing impaired a long time to learn a language, and the repetition is more pronounced. Language comes so easily to you that you don’t hear the repetition around you, the words repeated on the radio or television. But we hear so little that we only hear the repetition.

MH: Isn’t the audiologist a confirmation of what you’re unable to hear? He represents the limits of your subjects’ ability to hear, retooling them to the rule of the machine.

VT: The one mistake in the education of the deaf is focussing on the ability to hear rather than on your feeling and history. While the audiologist is asking her to respond to his tones, she may be feeling abandoned by her parents. If she’s feeling unloved by her mother, she’s not going to hear the test, her emotions overwhelm the physical fact of his voice. If a hearing person is feeling horrible, he’s not going to hear anything. That’s normal. Her whole world of emotions is being heard on the soundtrack, taking over the test.

MH: After the test we return to the woman seen in the film’s beginning, no longer alone now but playing pool with her lover. This is the woman that welfare is asking her to give up so she can have her child returned.

VT: I remember meeting the real woman and she said to me, “I need your help, I need to talk. I’ve lost my daughter.” I remembered this conversation and put our talk in the film. I was talking to Sue Lidster, the actor playing the role, I told her the horrible feelings the woman was having, and she recreated it. We had problems, not enough anger, not enough grief. I explained again and again until she got it. She’s not gay or deaf so it’s a very difficult role for her to play and she had to learn sign language at the same time.

MH: The camera is at an odd angle, looking on at the two of them from a distant corner of the table.

VT: I don’t like anything vertical or horizontal (laughs). I don’t like the squareness of the pool table or the screen, so I’m always cutting corners. You see how my place looks, it cuts corners. I relied a lot on the actors to make this movement inside the frame, to take away the straight lines.

MH: Unlike the scenes with the street kids where you cut out the consonants, this scene is simply out of sync.

VT: This was just another way of showing an audience the difficulties of lip reading. It begins about four frames out of sync and moves further and further out. I was trying to suggest that spoken language is no longer relevant to the woman, she’s willing to let her speaking go, and make sign language her mother language. Hearing impaired people were not encouraged to use sign language so they were forced to learn to talk. In this scene she accepts sign language as her own. But will she accept her own sexuality? In the end no one knows.

MH: After the credits roll there’s one more surprise at the end, a dramatic coda which features you and another woman speaking in an alley. You say to her: “You treat me like shit when we’re with other people and when we’re alone it’s okay.” She claims it’s none of your business how she acts in public. You reply: “I don’t care, it’s not my problem.” But if it’s not your problem, why bring it up at all?

VT: I think the last line is very important. It shows that you are saying to yourself that you are not the problem. The hearing impaired person is finally making an affirmation that she is not to blame, if society doesn’t want to accept them, it’s society’s problem. It’s like waking up and getting out of the circle, it’s a big step out. This scene was going to be the beginning, the foreshadowing of a sequel. I don’t know whether I’ll ever do it. It was a very depressing movie. I need a break right now.

MH: How much did the film cost?

VT: Simon Fraser gave me $1500 and I used $2000 of my own money, so it was quite expensive. I was living on coffee, nothing else.

MH: Human is a very difficult film which isn’t immediately accessible on a first viewing. How do you feel about making a film that needs to be seen more than once when most won’t have that opportunity?

VT: I watch film over and over again. Al Razutis taught me a lot. He said don’t rely on your audience, don’t seek its approval. Do what comes from your heart.

MH: Many of the filmers I’ve talked to here in Vancouver are in the midst of changing the way they work, often turning to feature length semi-dramatic productions.

VT: Maybe everybody’s tired of being poor (laughs). Stanislavski said, “Love the art in yourself, not yourself in the art.” Frank Capra said, “Don’t follow the trend. Start a new one.” It takes a lot of courage not to follow the trend, you’re going to be eating peanut butter for a long time. All the filmmakers here are islands, whereas in Toronto filmmakers are more together, helping each other.

It’s a real struggle for avant-garde filmmakers here to show work. Pacific Cinematheque is becoming more responsive now than three or four years ago. But they don’t show much. None of the universities are as interested in avant-garde film as they once were. Today students enter film schools with the idea of making Hollywood films. And it’s more difficult now to get the money to make avant-garde work. I applied to BC Film (a provincial funding agency) and they said my project was too experimental and that they wouldn’t fund any more experimental films. Meanwhile the lab has raised prices and reduced services.

MH: Are there any avant-garde filmmakers in Canada?

VT: No. An avant-garde is political. I think we won’t have an avant-garde in this country in this decade, we have to wait. In Europe the debate is very intense, or in Montreal where you have to fight for the freedom to speak French. Here we don’t have anything to fight for. I think British Columbia is the safest place in Canada. We don’t know what will happen to the country, if Quebec separates, many places will be affected, but not us. BC is very wealthy, a one language province. But the avant-garde in Europe always speaks about difference, different languages/cultures/themes. Here everything is the same.

This interview was recorded in 1990.