The Hours by Daniel Zalewski (2012)

How Christian Marclay created the ultimate digital mosaic

New Yorker, March 12, 2012

When Christian Marclay moved from New York to London, in the summer of 2007, he left behind some of his most valued possessions: hundreds of boxes of thrift-store junk. Marclay, the most exciting collagist since Robert Rauschenberg, had accumulated this trove over three decades, and relied on it to create his art. Many items had a connection to music, a dominant theme in his work. There were countless worn LPs, their covers bearing ghostly outlines of the vinyl inside; containers filled with bird’s nests of unspooled cassette tape; tatty theatre-geek scarves embroidered with musical notes stolen from Gershwin. The studio where he had curated all this stuff, in the former American Can Factory, in Brooklyn, was now a lifeless vault. Sawdust generated by the artist upstairs sprinkled through cracks in the floorboard ceiling, shrouding his things in beige snowfall.

Marclay liked to make something new by lovingly vandalizing something old. He remixed music—turning it inside out to foreground crackles and hisses—and he remixed objects that created music. He’d based dozens of projects on the vinyl records alone: scarring them with images, using a phonograph stylus like a lathe; melting them into cubes; piling them into menacing black columns. He even strapped a revolving turntable to his chest, as if it were a guitar, and videotaped himself whaling on a Jimi Hendrix LP. He says that his governing impulse as an artist has been to take “images and sounds that we’re all familiar with and reorganize them in a way that is unfamiliar.” In a 1991 collage, he arranged album covers so that Michael Jackson’s face and torso joined, uncannily, with the glistening bare legs of two women (one black, one white). Marclay, a fixture of the East Village music scene of the eighties, was particularly renowned as an avant-garde d.j.—in the late seventies, he’d been one of the first people to scratch records in performance, treating the turntable as an instrument. During sets, he sometimes smashed LPs, Frankensteined shards together with tape, and played the hiccupping results. To keep advancing as an artist, Marclay needed not just his mischievous imagination; he needed material to manipulate.

Marclay, who is now fifty-seven, went to London so that he could be with Lydia Yee, his partner, who had just become a curator at the Barbican Art Gallery. A Californian who grew up in placid Switzerland, Marclay hates histrionics, and he made no fuss about abandoning his bric-a-brac. But upon arriving in London he felt unmoored. “What am I doing here?” he asked himself. “How am I going to be able to work?” The apartment he’d rented with Yee, near the Barbican, was barely five hundred square feet. Though he had pieces in the permanent collections of the world’s top museums—including MOMA, the Whitney, and the Centre Pompidou—he wasn’t rich, and he couldn’t afford a large London studio. He settled on a grim nook, accommodating a five-foot-long desk, in shared office space on the fourth floor of a narrow town house in Clerkenwell. A window looked down on a courtyard, containing a tangled mass of crashed cars, where Fire Brigade members simulated extracting accident victims. Marclay was regularly rattled by fake cries of “Help!”

But Marclay has little need for luxury. He wears baggy, untucked button-downs that make his long legs resemble stilts. His putty-colored face has been left to its own devices by an indifferent buzz cut. He has a cheap aluminum Swatch whose hands resemble pencils, and he dutifully follows its dictates: his work hours are grinding and consistent.

Given his space constraints in London, Marclay decided that his first project would involve immaterial material—that is, digital media. Instead of wielding an X-Acto knife, he’d use Final Cut Pro. As he told me recently, sitting at his desk in Clerkenwell, “All I needed was this table and a computer.”

Though most of Marclay’s works had been tactile, he had made a few short videos, and they had received more critical attention than most of his other pieces. There was a reason for this: Marclay’s physical collages were dependably clever, but their impact often faded once you got the joke. (Rows of seating reupholstered with piano-score prints and images of instruments? “Musical Chairs,” from 1999.) Adding the dimension of time infused Marclay’s wit with drama. His best sculpture, “Tape Fall” (1989), had hinted at this potential. A reel-to-reel tape player, perched high on a ladder, plays water sounds, but the takeup reel is missing, so the tape cascades to the ground. The sculpture was recently shown again at Paula Cooper Gallery, in Chelsea; as the weeks passed, the tape pile rose balefully, like sand in an hourglass, and the burbling contraption became a relentless memento mori.

Video offered Marclay another way to play with time. In 1995, he completed a rapid-fire montage of movie clips depicting one side of a telephone call. The seven-minute “conversation” was as funny and stilted as the dialogue in a Pinter play. (“Darling, it’s me.” “What?” “The girl’s dead.” “Are you sure? Do you have a positive ID?” “Ah . . . no, not exactly.” “I’m so confused!”) “Telephones,” as it was called, was quietly revolutionary: one of the first video mashups, it was created a decade before the genre became ubiquitous on YouTube. Like its digital descendants, “Telephones” had a wrecking-ball quality; to look smart, it made its source material seem foolish. (Apple later asked to use the video for an ad launching the iPhone; when Marclay declined, the company aired a rip-off.)

He repeated his experiment with “Crossfire” (2007), an earsplitting installation featuring closeups of guns firing, especially the staring-into-the-cylinder shot favored by action directors. Marclay edited the clips into a loop of unnerving rhythms—pulsing techno-like beats, solitary booms—and screened four synchronized montages on the walls of a dark room. His organization of random violence was exhilarating and bewildering: should you dance or get the hell out of there? As the minutes wore on, however, “Crossfire” became oppressive; you felt like a thief being chased down a dank film-noir alley, with no chain-link fence offering escape.

Part of Marclay’s fascination with the cinematic archive had to do with the way it resisted transfiguration. It wasn’t hard to turn a recorded sound into an estranged abstraction, by slowing it down or folding it into a new rhythm. But, even if you chopped a film into a single frame, specificity clung to it: Audrey Hepburn, Givenchy, Manhattan, 1961. Marclay wondered if he could fashion from familiar clips a genuinely unfamiliar film, one with its own logic, rhythm, and aesthetics. In his view, the best collages combined the “memory aspect”—recognition of the source material—with the pleasurable violence of transformation. If Marclay could turn the sky green for one day, he’d do it.

His most thrilling foray into film collage came in 2002, with “Video Quartet,” which was commissioned by the San Francisco Museum of Art and acquired by the Tate. Four montages featuring actors and musicians playing instruments, singing, or dancing appeared, in calibrated unison, on a row of four screens. As in a chamber-music ensemble, one “player” took the dominant line—Judy Garland belting, Harpo Marx tinkling the harp—while other clips provided orchestration and rhythm. “Video Quartet” had the calculated riotousness of a Charles Ives composition, and it was often hilarious. Marclay repeated an Ann Miller tap-dancing stampede over and over, as if it were a badass drum solo. Just as the screens traded melodies, they parried visual rhymes: a clacking roulette wheel on one screen was countered by a whirling turntable on another. Museumgoers often clapped at the end—a rarity with video art, whose practitioners can pride themselves on being punishing. But “Video Quartet,” which lasted fourteen minutes, was a trifle in compositional terms. It was time to go Wagnerian.

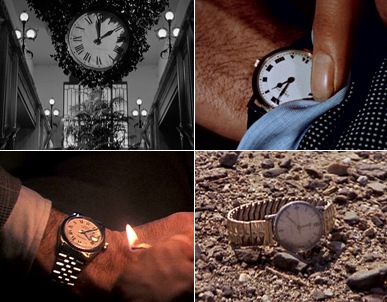

In Clerkenwell, Marclay recalled a performance piece that he once presented in Manhattan. He had combined film clips into a “video score” for an ensemble of musicians. The images—a surfer crashing, a flower folding up—were chosen to provoke diverse sounds. He titled the work “Screen Play.” (A devotee of Duchamp, he shares the Master’s love of horrible puns.) Though Marclay encouraged his performers to go wild, he wanted them to know their place in the score—it would help them give the performance dramatic structure. He decided that clips of clocks “would be interesting to use to mark time, to say, ‘You’re watching the seconds go by, and you know where it’s gonna end, because you actually see the time.’ ”

A techie intern was enlisted to scour the Internet for clocks. After embedding a clip—a boy in bed, checking his watch at 4:20 A.M.—in the opening bars of “Screen Play,” Marclay had a dangerous thought: “Wow, wouldn’t it be great to find clips with clocks for every minute of all twenty-four hours?” Marclay has an algorithmic mind, and, as with Sol LeWitt’s work, many of his best pieces have originated with a conceit as straightfoward as a recipe. The resulting collage, he realized, would be weirdly functional; the fragments, properly synched, would tell the time as well as a Rolex. And, because he’d be poaching from a vast number of films, the result would offer an unorthodox anthology of cinema.

There were darker resonances, too. People went to the movies to lose track of time; this video would pound viewers with an awareness of how long they’d been languishing in the dark. It would evoke the laziest of modern pleasures—channel surfing—except that the time wasted would be painfully underlined.

He would not be creating the first film with a running time of precisely one day. That distinction went to “24 Hour Psycho,” a 1993 work, by Douglas Gordon, that stretched Hitchcock’s taut thriller into excruciatingly portentous art. And Andy Warhol, in his 1964 film “Empire”—eight hours of stationary footage of the Empire State Building fading into darkness—had created a work whose point was to make viewers “see time go by.” There was a lineage of avant-garde cinema that, with varying degrees of obscurity, examined the temporal qualities of film. Marclay’s contribution to the cinema of duration, though, would be pleasurable to watch. He sensed a creepy challenge. If his film was sufficiently seductive, he might coax people to sit for hours, literally watching their lives tick away. Though at any given minute the film would have the weightlessness of a Hollywood trailer, in its entirety it would be an even heavier memento mori than “Tape Fall.”

Marclay “had the spark,” as he put it, but he was daunted: how many clips would be required to fill up twenty-four hours? In most film sequences, the camera lingers on a clock for a few seconds. “I didn’t have the courage to get started, because I knew it would be an endless struggle,” he said. But now, in London, he decided to see if he could build the defining monument of the remix age.

Marclay proposed the project to White Cube, the proudly slick gallery that represents him in London. “Even though none of us were sure that it would be possible to make, the concept was so exciting that we wholeheartedly committed,” Jay Jopling, the gallery’s owner, recalled. Marclay’s budget exceeded a hundred thousand dollars. White Cube’s signature artist is Damien Hirst—a man who has made a diamond-encrusted skull—so Marclay’s sum seemed comparatively paltry. Moreover, the cost would be partially covered by Paula Cooper Gallery, which would show the video in New York.

Craig Burnett, an associate director at White Cube, told Marclay to consider the first six months a “feasibility study”; by then, he’d know if the global archive of cinema could accommodate his thin-slice vision. One issue that didn’t give Marclay pause was copyright, because nobody had objected before to his appropriation art. He had a theory: “If you make something good and interesting and not ridiculing someone or being offensive, the creators of the original material will like it.”

For “Video Quartet,” Marclay had spent months pestering clerks for clips at Kim’s Video, in the East Village. But this time he’d need foragers. “I could do it, but it’d take me ten years to collect,” he said. Still, he didn’t want to outsource its construction, in the manner of Jeff Koons or Takashi Murakami. Marclay believes that “art is all in the details,” and so he committed to handling what mattered most: the editing. The key to his video projects, he believed, was the artfulness of the transitions, which reassured the viewer that a tactical intelligence controlled the flow of imagery. He also felt that the clock video would not cast a spell if it had the blunt cuts of its Internet cousins—those “supercut” compilations of Hollywood clichés, such as action heroes deadpanning, “We’ve got company.” He wanted his supercut to emulate the rhythms of a Hollywood feature. Others could collect the thread, but Marclay would weave the tapestry.

Marclay’s monstrous creation needed a title. He thought of a few of his usual puns: “Time Piece,” “Clock Work.” Then he and Burnett discussed the matter, and decided that the work was too grand to be trivialized with wordplay. Better, Marclay decided, to call it “The Clock.”

At Marclay’s request, White Cube posted a “Help Wanted” sign at Today is Boring, a cinéaste redoubt on Kingsland Road. Six young people were hired to watch DVDs and rip digital copies of any scene showing a clock or alluding to the time. (Sophia Loren to Marlon Brando: “I can’t appear at eleven o’clock in the morning in an evening dress!”) Files were logged with search-friendly titles: “1124—kid waiting on streets/old man checks watch—Paper Moon.” The assistants recorded their discoveries on a Google spreadsheet, to avoid overlap. Since a rival version could be hastily crowd-sourced on the Internet, the assistants signed nondisclosure agreements.

Each afternoon, Marclay was presented fresh clips: the “catch of the day.” At first, he was merely collecting scattered files, but eventually he had enough to forge “hinges” between them. The more hinges he came up with, the more inventive they got. At 10:30 P.M., Marclay realized, a shot of David Strathairn, delivering the news as Edward R. Murrow in “Good Night, and Good Luck,” could slide into Dustin Hoffman, in “Tootsie,” watching television. To create continuity, the Murrow dialogue was extended into the “Tootsie” clip, at muffled volume.

Marclay relished such sly incongruities. He wanted to make an expertly edited film that exposed the fakery of editing. “By putting the clips back into real time, it’s contradicting what film is,” he explained. “You become aware of how film is constructed—of these devices and tropes they constantly use. Like, if someone turns abruptly, you expect someone else to be in the next cut. An actor looks down at his watch and, suddenly, you have a closeup of the watch. But, if the first clip is in black-and-white and the next is in color, you know you’ve been fooled.”

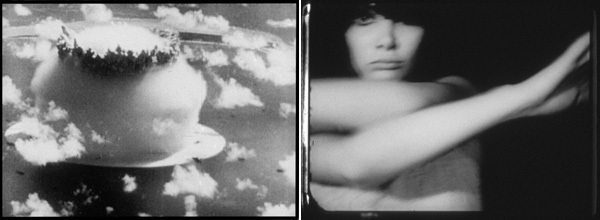

These absurdities echoed the seminal 1958 film collage “A MOVIE,” by Bruce Conner, which juxtaposed clips from old films to comic effect. “He definitely had an influence on my understanding of editing,” Marclay said. “I admired his odd transitions.” In the film’s most famous sequence, a submarine captain sees something unexpected through his periscope: a voluptuous girl in a bikini. Conner’s collage piles on the spectacle: the captain aims a torpedo at the girl, and the next shot is of a mushroom cloud.

Marclay wanted “The Clock” to feature the occasional outlandish fragment—an explosion from “The Aviator,” at 11:17 A.M., led into Al Pacino looking startled, in “88 Minutes”—but he felt that overrelying on melodrama wouldn’t work in such a long video; it would be like composing an opera with nothing but cymbal crashes. To inspire queasy contemplation of lost time, he emphasized more incidental moments: a woman applying deodorant before a mirror, a depressed man fussing with his crooked tie. Between 7:09 P.M. and 7:18 P.M., there are four clips from Claude Chabrol’s “This Man Must Die”—images of a cigarette left burning in an ashtray. (A table clock is nearby.) “The burning cigarette is the twentieth-century symbol of time,” Marclay said. “As a memento mori, we used to show a candle, but a cigarette is so much more modern. Yet it’s the same thing—you see time burning.”

“The Clock” turned actors into a more chilling kind of memento mori. At 12:27 A.M., there was a clip of a resplendently dewy Catherine Deneuve, then twenty-one years old, from “Repulsion.” Four hours later, she’s three decades older, in “My Favorite Season,” an embittered wife intentionally knocking a clock off a fireplace. At 1:51 A.M., Jack Nicholson is a frantic juvenile delinquent in “The Cry Baby Killer”; at 4:59 P.M., he is the paunchy and bald hero of “About Schmidt,” gazing at his office clock as he torpidly awaits retirement.

The video’s melancholy strain was, in part, an aesthetic choice, but it was also dictated by the material. We look at clocks, after all, in order to shackle ourselves to a schedule. In films and in life, eyes consulting a clock usually look disappointed, harried, or distressed. At 11:30 A.M., the point was underscored by a montage of jittery people shouting things like “I need ten minutes” and “There’s no time!” In Marclay’s hands, clocks became instruments that destroyed contentment, as when Julia Roberts, dreamily caressing Clive Owen in bed, realizes with dismay, “It’s twelve-fifteen!”

Marclay’s head assistant, Paul Anton Smith—a laconic, long-haired Canadian with a passion for Golden Age cinema—understood that his boss coveted moments that were “banal and plain but visually interesting.” Smith explained, “If there was someone making tea, it helped if it was a clip from the sixties and it was a cool-looking kettle.” Other assistants didn’t get it, Marclay said. One fellow, who offered little but gunshots and “guys getting their heads chopped off,” was fired.

The surviving assistants specialized in different genres, and all of them yielded images of timepieces except Bollywood films, which were oddly clockless. Marclay was often surprised by his assistants’ viewing choices. “I probably would have made different selections,” he said. “But you have to accept what people bring to you. I’ve worked with collage a lot. And there’s this chance thing that happens—you don’t always control things. Why did you find this today and not this? But you’ve got this thing, and you make it work. It’s the way life is, I suppose. Whatever happens, you deal with it.”

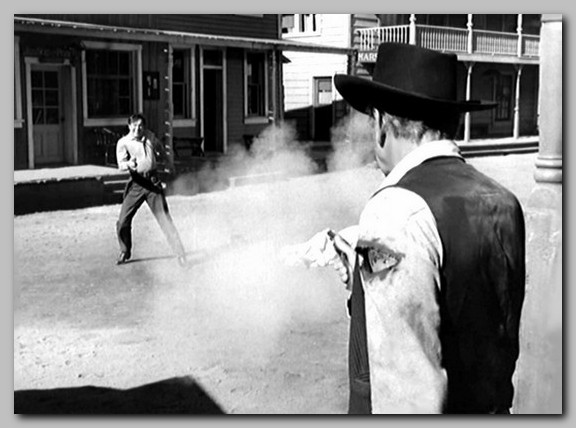

Some sequences in “The Clock” were inevitable—at noon, “High Noon.” But Marclay’s video rendered even that material strange. In Fred Zinnemann’s film, the fateful hour is preceded by a gallery of anxious faces intercut with a pendulum clock. “It’s condensed in the actual film,” Marclay explained. “I put all of that back into real time.” His video upended a central illusion of film. Theorists like Henri Bergson had dilated on the falseness of cinematic “duration”—the way that, say, the swirl of a long drunken evening can be captured in a set piece lasting three minutes. Marclay made the same point, but viscerally.

Though “The Clock” subverted many cinematic tropes, it participated in others. When a movie emphasizes that it’s five minutes to four, it’s meant to raise anticipation or anxiety. In Marclay’s video, too, there was an artificial rise in tension before almost every hour, and a slackening afterward. He decided to make comedy of it. The lead-up to noon accelerated toward mayhem, with flame-haired Lola running down the streets of Berlin while Debra Winger leaped out of bed in Algeria and Leonardo DiCaprio dashed to catch the Titanic. At 12:01 P.M., the video abruptly returned to boredom: Burgess Meredith, as a bank teller, silently putting up a “Next Window, Please” placard. At the end of the six-month trial period, Marclay had amassed several extended sequences, and he told White Cube that he could accomplish his feat—eventually. His computer was getting so clogged with data that a second machine was added. One G5 was reserved for midnight through noon, the other for the remains of the day.

If a filmmaker made a montage of Marclay editing his epic video, it would show a man aging by three years while locked, ten to twelve hours a day, in front of a computer. There would be many closeups of Marclay wincing from his aching back. About halfway through the sequence, the artist’s right wrist would become entombed in a tan Velcro prosthetic support.

“It was a gruesome three years,” Marclay told me. “But I became addicted to finding those little solutions. It gives you a bit of a high. You put two things together, and you get, like, ‘Oh, my God, this works!’ ” He admitted that he sometimes dreaded the arrival of fresh clips: “The worst was when I worked really hard on figuring out a nice transition at 10:46 A.M. and someone would bring another 10:46, which was better footage or worked better with the narrative. There was constant remodelling.”

“The Clock” started sprouting leitmotifs: men with hangovers smashing alarm clocks, late travellers racing across train platforms. Such sporadic recurrences, Marclay felt, rewarded attention and knit the work together. Smaller themes, connected to a particular time of day, sang out and then faded. In the early evening, Marclay inscribed a pattern of women being disappointed by their husbands. At 7:14 P.M., Liam Neeson calls Julianne Moore, who’s planned a surprise party for him, to say that he’s missed the flight home; four minutes later, Moore, this time in “Far from Heaven,” tells a servant, “It’s nearly twenty after and Mr. Whitaker still hasn’t phoned!” At 7:19 P.M., Steve Martin promises his wife, “Shouldn’t be any later than ten.” The capper is Katharine Hepburn, preparing place settings for a dinner party while fuming over an absent Spencer Tracy: “Isn’t that typical! Twenty minutes of eight.” For all its jokes, the video was emerging as the first mashup to be deeply moving.

The 5 P.M. hour was the first to be completed—movies so often depict characters leaving work. As the subsequent hours filled in, there were some coups. One evening, Paul Anton Smith watched “The Woman in the Window,” a Fritz Lang noir. The corpse of one character, Claude Mazard, is discovered, in the sewers, at 11:44 P.M. The film cuts to a closeup of his pocket watch, monogrammed with the initials “C.M.” Marclay suddenly had his version of a Hitchcock cameo.

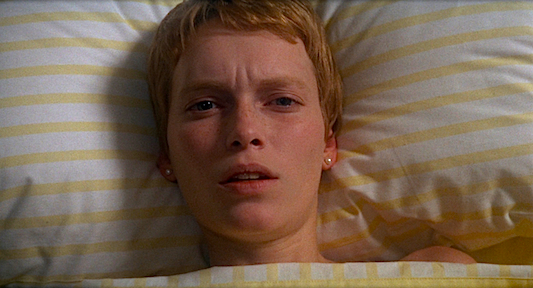

The montage method ruthlessly exposed the quality of an actor’s performance. In a seven-second clip, the line between feeling and fakery becomes painfully clear. At 4:09 P.M., there’s a shot of Mia Farrow in “Rosemary’s Baby,” lying in bed; her face subtly conveys that her distress will tip into lunacy. But when Sandra Bullock is seen, at 10:15 A.M., waiting in a conference room for Hugh Grant, and tapping a pencil like a jackhammer, her anxiety seems as contrived as Kabuki.

To keep the desktops of each Mac uncluttered, Marclay set up folders for every hour. This decision yielded a narrative strategy: the clips in each folder often suggested a theme. The 8 P.M. folder held many clips of characters attending the theatre, so he filled in the gaps with scenes of heightened drama. At ten o’clock, several clips of women drinking alone prompted a theme of sadness.

Marclay began thinking of the hours as chapters in a novel. This seemed fitting: in building a monument to the drama of a single day, he was following the lead of “Mrs. Dalloway” and “Ulysses.” Marclay told me that the process made him feel like a writer: “You have to sit down every morning at your fucking computer and just do it. If you write three sentences? Fine.” Just as the sentences in a novel build into patterns and story lines, so did Marclay’s clips. One actor whose star was reborn in “The Clock” was Joan Crawford, who in the video becomes a sinister nocturnal creature—she appears nearly a dozen times, always intensely plotting, whether she is putting on gloves (7:41), starting a fire (9:03), administering medicine (10:49), snooping in drawers (10:57), stopping a clock from ticking (11:25), drinking a cocktail in a black sequin dress (11:48), hiding behind slotted blinds (11:52), or staring at a pendulum (2:25).

Marclay found that a few clips of a film, spaced apart, could create effects more trenchant than the original movie. At 9:52 A.M., Jodie Foster, poised to confront her rapists, is told to wait in an antechamber; the cruelty of this delay registers at 11:16 A.M., when another clip shows her finally entering the courtroom. Seven minutes before noon, Charlie Sheen is stoked for an interview at Gordon Gekko’s firm, declaring, “Life all comes down to a few moments. This is one of them.” At 5:23 A.M., Sheen brusquely nudges a one-night stand out of bed as he walks over to a computer to begin trading. These bookends convey his entire dissolution.

At the same time, “The Clock” was a sprawling anti-narrative; like a churlish Robbe-Grillet novel, it toyed with your impulse to create a coherent story. Marclay often included several clips from a movie in a single hour, daring viewers to anticipate a big plot turn—which never arrives. Nine clips show residents of Elm Street preparing for sleep, but Freddy Krueger doesn’t appear. At 11:57 P.M., a young Vanessa Paradis proposes sex to a boy while disrobing him. At 1:19 A.M., they’re sleeping in separate beds. Did they do it?

At midnight, Marclay constructed a wicked trap. There is a sweeping build: an American in London howls like a werewolf; Gary Oldman howls as Sid Vicious. Orson Welles, in “The Stranger,” plummets off a clock tower. Finally, there is a shot of a clock that has loomed oppressively in the video, appearing dozens of times: Big Ben. It’s obliterated in a fiery explosion—a clip, from the wretched “V for Vendetta,” turned golden through the alchemy of remixing. Yet Marclay undercuts this seeming climax. In the next minute, he segues to a scene in London in which Rhett Butler’s daughter wakes from a nightmare. As Butler comforts her, the window behind them frames Big Ben, fully intact. Marclay has turned the apparent crux of “The Clock” into a mere dream. “You always feel tricked when that happens in movies,” Marclay said. “And the video, in a way, is one big trick.”

In September, 2010, Marclay returned briefly to New York. White Cube had scheduled the video’s première for October, but there was a hitch: hundreds of transitions worked visually but not sonically. For help, he had enlisted Quentin Chiappetta, a Brooklyn sound designer who had worked on “Video Quartet.” Holing up in a warehouse in Williamsburg, they tweaked the soundtrack with Pro Tools. Chiappetta told me that Marclay, as a d.j., viewed easy solutions with contempt. “He doesn’t like fadeouts,” Chiappetta said. “He thinks it’s weak. It’s his work with turntables—the easiest way to get out of a spot is to turn the knob down. So to do it in a more clever, rhythmic way became the goal.”

Sometimes, as with Dimitri Tiomkin’s stirring score for “High Noon,” the soundtrack of one movie was laid under dozens of neighboring clips, binding them together. In other cases, a score was shifted in pitch or speed so that it merged with the next. Noise was gradually added to a pristine surround-sound clip, easing the shift into a crackly mono one. Such remastering made it “so that you didn’t notice clips were ending, so that you were continually pulled along,” Chiappetta said.

The sound collage became ten times as intricate as the visual collage. A number of scenes received entirely new soundtracks, to striking effect. At 11:33 A.M., there’s a fantastically tense sequence of Dana Andrews, in “Laura,” snooping around Clifton Webb’s New York apartment; it’s virtually silent, and every footstep feels like an earthquake. The original is not suspenseful in the least—it’s dominated by Webb’s tough-talk voice-over. Sometimes, Marclay created new sound effects. A clip, at 6:49 P.M., showing Kevin Spacey shaving, was marred by distracting audio; to redo the soundtrack, Marclay stood in a sound booth and pressed the nozzle of a Noxzema shaving-cream can in sync with the visuals.

As the première date approached, a few holes remained. “There was a point where it was, like, ‘How are we going to deal with 3 A.M. and 5 A.M.?’ ” Marclay said. “Those were tough. The hardest was five.” At that hour, Smith and his crew couldn’t find time-stamped clips for fifteen of the minutes. Marclay hit on a solution. The later that viewers stayed up watching “The Clock,” he surmised, the more “strung out” they would become. “You have to imagine that, if you’ve been up watching and it’s 5 A.M., you’re in a weird state of mind,” he said. “I decided to play with that.” He completed the late-late show with more than a dozen dream sequences, including the classic Dali nightmare from “Spellbound.” It worked, because so many of the clips in between showed people agitatedly tossing in bed.

In the end, more than ten thousand clips were collected. The first screening was at White Cube’s austere gallery in Mason’s Yard. Jopling and his staff told Marclay that he’d produced a masterpiece. Sure, it was fun to try to identify all the clips whizzing by. But “The Clock” was no game. By presenting a day in the life as a ceaseless parade of fictional narratives, he had confirmed Joan Didion’s dictum that “we tell ourselves stories in order to live” while reminding us that we are all going to die.

“Time’s up,” Marclay said, tapping me on the shoulder. “I’m ready to go out for dinner.”

It was 7:29 P.M. Onscreen, Nicole Kidman, in a Manhattan bathroom, was also ready to go out, asking a distracted Tom Cruise if her hair looked pretty. Offscreen, we were in a third-story gallery, enshrouded in black velvet curtains, in Yokohama, Japan. It was August, and the city, a southern satellite of Tokyo, was celebrating the opening of its Triennale, a contemporary-art exposition. “The Clock” was being shown in a warehouse on the waterfront; it was the anchor of the show, which had been given the companionable title “Our Magic Hour.” Several works on display were apparent tributes to Marclay, such as a video of a Japanese artist using a turntable as a potter’s wheel.

I was happy to be interrupted. My body had been locked in symbiosis with “The Clock” for some three hours, and my stomach had been growling ever since cooking sequences had begun proliferating, around five. At 7:25 P.M., not long after Juno’s family starts in on the baked potatoes, a French matron is shown chopping vegetables, her metronomic rhythm evoking a loudly ticking watch.

Marclay, who had flown in from London the day before, was jet-lagged and disoriented: when he’d guided me into the installation, he stood in front of a closeup of an elementary-school clock, indicating 4:29 P.M., and asked me what time it was. His exhaustion was a happy consequence of success. “The Clock” has become as iconic as Jeff Koons’s flowering “Puppy” or Damien Hirst’s taxidermied shark—and Marclay had risen from art-world respect to international fame. Though “The Clock” was the evolutionary outgrowth of decades of remixing, it registered as a shocking leap in ambition, as if a dedicated short-story writer had suddenly published a Tolstoyan novel.

“The Clock” was on a global tour, and seeing it had become a competitive sport. In London, attendees lined up and camped overnight in order to catch it. In Los Angeles, a film maven gulped it down in one sitting, purportedly without a bathroom break. In New York, it was shown at Paula Cooper Gallery, and when Sofia Coppola saw it—“Lost in Translation” is memorialized at 4:20 A.M., when Bill Murray is jolted by an incoming fax—she told the gallery that she felt honored by Marclay’s borrowing. Roberta Smith, of the Times, called “The Clock” the “ultimate work of appropriation art.” Rosalind E. Krauss, the eminent art historian, hailed Marclay’s transformation of “the reel time of film into the real time of waiting.” The praise was widespread enough to incite hipster backlash: posters, along Twenty-first Street, announced, “NOTICE: Christian Marclay’s 15 minutes of fame will expire in 24 hours.”

In the summer, “The Clock” opened at the Venice Biennale, and Marclay won its Best Artist award. It was a delightful venue, he said, because “on the hour you’d hear all the church bells ringing in the neighborhood—it was so nice to hear the world intruding.” There were also stops in Seoul, Moscow, Paris, Boston, and Jerusalem, and the waiting list has grown long. “The Clock” is currently on display at the National Gallery of Canada, in Ottawa, and soon it will return to New York. Plans are afoot to exhibit it at Lincoln Center this summer, and MOMA, which bought a copy for its permanent collection, will follow.*

“The Clock” is far too long to be presented on a DVD. The work is a computer program—coded by Mick Grierson, a professor at Goldsmiths College, in London—that, when booted, launches into whichever clip matches the time, down to the microsecond. The system, which archives the video and audio tracks separately, requires setup, and Marclay and a White Cube technician, Scott Martin, were present at virtually every city where the piece had been shown. (As carefully tended as the system is, mishaps can occur: at the Pompidou, “The Clock” mysteriously fell a few minutes en retard.)

In Yokohama, we were sitting on the same kind of ivory-colored IKEA couch that Marclay had chosen for the presentation of “The Clock” in London and New York. Martin, a lanky Englishman, had entered with Marclay, and he joked, “He should have a sponsorship deal.” Marclay had approached the matter of seating with typical fastidiousness. The sofas, arrayed in a grid, allowed viewers to sit comfortably for hours, and to leave without forcing others to stand up, as in a cinema. In Japan, however, visitors insisted on standing, and when I was there artgoers crowded in the back of the room, like the staff at Downton Abbey.

Despite Marclay’s reminder about dinner, we didn’t leave right away. Like everyone else in the gallery, he got a zombie glint in his eye once he looked at “The Clock,” and for a while we watched together. The stepping-out theme was elaborated: now Daniel Craig and Eva Green were in a bathroom, preparing to gamble at the Casino Royale. I asked Marclay if he could identify various clips. Either he couldn’t or he could answer in only the vaguest terms. “That’s French,” he said at one point, as Alain Delon spoke French. Later, I asked Marclay to name the last film he’d gone to see. He struggled to come up with a title, and, when he did, it was nearly a year old: “The King’s Speech.” “I really know nothing about cinema,” he said. “It’s terrible.” Because Marclay travelled frequently for exhibitions, he sometimes caught movies in hotels, but he rarely watched the whole thing. Even when relaxing, he’s a collagist. “I don’t mind seeing a lot of fragments of a film,” he said, with a shrug.

Marclay’s remove from his primary material was a bit unsettling—the definitive homage to Hollywood had been conceived by someone who had rarely felt the popcorn beneath his feet. But his lack of expertise gave him an aesthetic distance that obsessed fans lacked. “It’s the same way with music,” he observed. “The fact that I know very little about music, but I make music, is very liberating.” His first breakthrough, at art school—the Massachusetts College of Art, in Boston—came when he discovered a record for children on the street. The disk was covered in scratches and tire tracks, and Marclay listened to it on a record player at school. A warped rendition of the “Batman” theme issued forth, and the idea of distorting music through physical distortion took hold.

This was in 1977. Why hadn’t he played the record in his room? “I didn’t own a turntable,” he explained. “I never even listened to that much music. I went to a boys’ boarding school in Switzerland, and we weren’t allowed to own it.” During high school, Marclay tried to begin piano lessons, but he was told that he was too old, and he decided to cling to his musical illiteracy. When he first mounted live musical performances, with a classmate in Boston, he flaunted his lack of training, making beats by chopping wood and smashing glass; at least once, he bled onstage. Such savvy naïveté attracted the attention of John Zorn, Sonic Youth, and other skilled noisemakers on the punk scene, who made him one of their own. (A grainy video on YouTube shows Thurston Moore, Sonic Youth’s guitarist, blasting away with Marclay, who performs with the cold concentration of a piano tuner.)

Onscreen, a perky synthesizer added bounce to a B-movie from the eighties. We spoke of the intensely musical feel of “The Clock.” He and Martin had advised me to experience the video for a stretch with my eyes closed, and I did. It was a cool remix: the time is invoked in dialogue every few minutes, and you appreciate more deeply the way that, at 6:45 P.M., a New Wave beat sneakily penetrates the clamor of a party scene from “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” heralding the subsequent clip—a gallery scene from “Basquiat.”

Marclay was wearing a blue hoodie from the Gap and black Vans—the not-too-crazy ensemble of an aging d.j. His experience as a turntablist is essential to “The Clock”: it has impeccable timing, flowing from frantic to stately, with some clips stretching past a minute. “In a music video, the image follows the rhythm of the sound and you get a lot of that fast jump-cutting,” Marclay said. “I’m sick of it. It was created to hold your attention, but it doesn’t anymore.” Marclay’s aim was to “make a collage with continuity.”

Actually, he said continue-tee—his English is flawless except for an occasional mispronunciation. Though he was born in San Rafael, in 1955, his American mother soon agreed to move to a suburb of Geneva, where his father had a business making dentures. The family was a linguistic scramble. His parents had met in Peru—his father was travelling, and his mother was preparing for a master’s degree in pre-Incaic textiles—and Spanish was their only shared language. His mother, who became a homemaker, spoke to Christian in English, and it took her a while to learn French. Marclay attributes his interest in art to the fact that he “didn’t trust language that much.” He recalls, “Often my mother could not help me with my schoolwork because she was not fluent in French. I relied more on images.” The collagist instinct came early: he remembers a grammar-school teacher who “found these big sample books of wallpaper, and we could draw on them. I loved that.” She also let him play with the mimeograph machine.

We exited the screening room and briefly paused before a mud sculpture of a hippo. Marclay raised his eyebrow and moved on. He is honest in his assessment of his contemporaries. Damien Hirst’s career held little interest for him, he said, because Marclay is attracted to ideas, not to “a cult of personality.” After I mentioned admiring a shimmery video by Bill Viola that had accompanied a New York performance of “Tristan und Isolde,” he said, “I don’t like his stuff very much,” adding that he was skeptical of the trend of embellishing concerts with visuals: “It’s a little pandering making something theatrical more easy to digest because there’s an image.” When asked to name contemporary artists he did like, Marclay mentioned Gabriel Orozco, then added, “I don’t like everything by anybody.” Unqualified praise is reserved for canonical forebears: Duchamp, Bruce Nauman, John Cage. For all his firsts, Marclay doesn’t have the revolutionary impulse; he wants to be part of an illustrious tradition.

We left the exposition gallery and waited for a taxi. “Notice how anthropomorphic the cars are here,” he said at one point. “You can tell it’s Japan just by looking at the orderly movement of the traffic.” We were picked up by a white taxi whose dashboard bore a large black clock face: 8:04 P.M. Because it was now as dark outside as it was in the gallery, I felt a disquieting porosity between the cinematic and the real. Marclay warned me that, for a while, I’d notice clocks with distressing frequency. It was true—for days, I felt stalked by the time.

The restaurant was in an antiseptic hotel next to the city’s convention center. To get there, we walked through a concrete expanse with a view of Japan’s tallest skyscraper, but Marclay took no notice of the landmark. The next day, on the same plaza, he stopped abruptly and declared that he could hear cicadas. The bugs add a high-pitched thrum to many tree-lined streets in Japan, but something was up: there were almost no trees here. A recording, Marclay surmised, was being piped in—an artificial scheme to make the space seem less artificial. He tends to ignore obvious enticements and notice the marginal. After a press conference held the day the exposition opened, his sole comment was to say that he enjoyed the collective rustle of a hundred Japanese journalists opening their press packets.

The restaurant had a wide-angle view of the harbor. We sat down by the window, and soon after we ordered Marclay’s face was tinted by a rainbow splash of neon. Yokohama’s harborfront features an enormous Ferris wheel that is also billed as the world’s largest timepiece. The spokes of Cosmo Clock 21 glow green at night, and when it completes a rotation the entire wheel erupts in color. The time was 9:30 P.M., and the digital numerals at the wheel’s center loomed directly over Marclay’s bristly head. It looked like a frame from a Michael Bay movie—an unsuspecting diner, just before a time bomb shatters the window into C.G.I. smithereens.

The Yokohama clock was a beloved public spectacle. So why was “The Clock” kept hidden inside small gallery rooms? “When I first started on this project, I thought it would become a public art piece,” Marclay said. “I thought, What a great thing, to be in a train station waiting for a train and being able to watch a movie. It would inform you what time it was, and at the same time entertain you. But I realized it was impossible—there’s lighting issues, sound issues, you have to hear the public-address system. And Grand Central, for example, closes for a few hours, late at night, when they clean up the place. Then there’s the occasional nudity and swearing. How do you show that at Grand Central? And then you start censoring yourself, and you can’t do it.” But there was a more important reason that the video needed to exert a tyrannical hold in a dark gallery. Shown amid other distractions, it became an ambient object: just another clock.

Craig Burnett, of White Cube, had told me that Marclay was “very sweet, polite, and gentle,” and that “the only time I’ve seen him angry or negative is when people are very casual with his work.” Marclay admitted that he’d been infuriated by many museum curators who hadn’t thought through the subtleties of his video. They wanted a Ferris wheel, not “The Clock.” According to the Art Newspaper, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art had proposed projecting “The Clock” on an exterior wall. Marclay said of this idea, “You know, it’s ‘Let’s tell the world that we have it.’ But what happens during the day? It’ll fade out. And what about the audio track?” (LACMA denies suggesting outdoor projection.) Negotiations with Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts had been even more frustrating. Though the museum had already announced a plan to screen “The Clock,” its curators had not yet presented Marclay with an appropriate setting for the video—he had rejected proposals to show it in a sunny atrium or in a wood-panelled auditorium. And lawyers at the Tate wanted him to sign a contract effectively permitting curators to show “The Clock” in Turbine Hall, which accommodates huge crowds but, according to Marclay, has “the worst acoustics in the city of London.”

At the risk of seeming difficult, he wanted the video to be shown exactly as he’d planned it, down to the IKEA couches. “The Clock” was a twenty-four-hour video with a twenty-four-page instruction manual. “Venerable museums are acting like greedy kids,” he said at one point. “There’s a lack of scholarship. It’s all about how many people they can get through the doors. How to preserve it, how to give it the best possible presentation—that doesn’t matter. They just want a hit.”

Of course, it was flattering to be the center of a global bidding war—the Pompidou and the Israel Museum were among the museums vying for one of the six copies that White Cube had made of the computer program. “The Clock” had certainly made Marclay wealthier: five copies, intended for museums, were being sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars, and the sixth had been sold to Steven A. Cohen, the Connecticut hedge-fund manager, for an undisclosed sum. (Cohen started showing the work on a monitor in his office, as if it were a fancy screen saver.)

Still, Marclay was recoiling a bit against the success of “The Clock,” like an indie rocker who starts refusing to perform his No. 1 hit. At the opening party for the exposition, held the next afternoon in a hangar-size conference room, Marclay was polite when people from New York, L.A., and Tokyo told him how much they adored the video, but he beamed when he was approached by people who loved his old stuff. A young artist featured at the Triennale, Lyota Yagi, told him, “You are my idol.” Experimental-d.j. culture flourishes in Japan, and Marclay, who has released several recordings of turntable work, is considered a pivotal figure. Yagi told Marclay that he had recently made several records out of ice. A video at the exposition showed him playing them until friction from the stylus reduced them to slush. The ice exaggerated Marclay’s favorite attribute of an LP: the crackles that confirmed its fragility. He asked Yagi which music sounded best frozen. Chopin’s Nocturnes, he replied.

Then the question came: “What’s your next video, Christian?”

After three monastic years of digital collage, Marclay ached to return to analog art. “I don’t want people to think I’m only a video artist—the guy who did ‘The Clock,’ ” he told me. “I make so many different things.”

And so we went shopping. Marclay had started two projects involving manipulation of Japanese art forms. For a solo show at Tokyo’s Koyanagi Gallery, he was making Japanese hanging scrolls: paintings, surrounded by cloth borders, that are unfurled for tea ceremonies. His provocation was to design scrolls with aggressively unsoothing imagery and fabrics; the paintings, traditionally serene nature scenes, would be replaced with scanned collages depicting explosions and other havoc, hand-assembled from ripped bits of comics. Digitally enlarged, the wood fibres of the torn paper resembled exposed entrails, connecting “the violence of the comics and the tearing of the paper.” The border fabrics would be things like neon prints and Pucci swirls. This raucous palette was, perhaps, a more honest evocation of modern Japan.

Sho Kuwajima, a highly poised staff member from the Koyanagi Gallery, chaperoned Marclay through Yokohama’s textile emporiums—hushed feminine enclaves of blond wood. At one store, Marclay purchased some apple-green fabric whose irregular circles reminded him of the Benday dots in comic books. At another store, he called me over and said, “This is interesting! It’s almost like caramel camouflage.” He thought the fabric might make a nice border.

Next, we went on a hunt for manga. Japan’s comic books are famed for their bold ink graphics, but Marclay also considered them musical objects, because the action is frequently highlighted with explosive onomatopoeias of the “WHKOOM!” variety. In 2010, for a solo show at the Whitney Museum, in New York, he’d lined up manga sounds on a sixty-foot-long scroll, creating a graphic score for an improvising vocalist.

Now he had enlisted a Tokyo publisher, Akaaka, to print a comic book that would be composed entirely of bits from other manga. The book, he said, would be another “abusive, destructive” act, a brash distillation of an entire art form. He had made a few manga collages already, and found it invigorating; compared with the wonky constraints of “The Clock,” he said, it was “a very different kind of thinking—it’s very loose.”

I saw the test collages, and, considering that they were made from glued paper, they were impressively kinetic. One combined fragments of ocean waves and bomb clouds into a colossal vortex; by comparison, the famous Hokusai image of a tsunami seemed like a bathtub slosh. Marclay’s scissor cuts were crude, making you conscious of looking at many overlaid images at once. He heightened this effect with an absurd pileup of sound effects: a leaping female warrior, gun in hand, was surrounded by “FWAP,” “SHOOM,” “RAAA,” and fourteen other sound words, making it seem as if many violent acts were occurring simultaneously. The result was almost old-fashioned: comic-book Cubism. The collages were small, and pointedly anti-epic. It was as if Richard Serra, after completing his Torqued Ellipses, had gone off to make a torqued lampshade.

Marclay wanted to make three hundred such collages; like “The Clock,” the project would require sustained toil. A manga periodical often contains several long stories, each on a different shade of pastel paper, and his project would mimic that scheme, with “folios” for various groupings—natural disasters, say, or erotica. Marclay wanted the book to look enough like a real manga that a clerk would misfile it and “put it in the comic section, not the art section.”

We stopped in a junky convenience store that had a long shelf of manga, much of it pornographic. Riffling through the books, Marclay zeroed in on the sexual onomatopoeias. “Japanese is so weirdly specific,” he said, chuckling. Kuwajima, asked to translate, stiffly complied. “That means ‘thrust deeply,’ ” he said of one kanji character.

Marclay pointed to a closeup of breasts. “That kanji sounds like whhhhr,” Kuwajima said. “It means ‘bounce really, really fast.’ ”

Marclay ended up with a stack of books. “This is all stuff for my scissors,” he said. For the first time in a while, he had fresh material to menace.

In September, Marclay was back in London, struggling to make headway on the manga book. His initial plan was to complete one collage a day, every morning, at home; at that rate, he’d finish within a year. But scraps of manga had spread throughout his tiny apartment with entropic malice, and though he found it helpful to live with his puzzle pieces—“You’d get ideas when you weren’t even thinking about it”—the situation created insupportable clutter. In Clerkenwell, Marclay acquired a second desk, which was now dedicated to manga. When I visited him there, the desk was covered in visual shrapnel—next to a yellow highlighter was a pile of dismembered feet.

Marclay’s other desk had been pushed against a dormant fireplace whose hearth displayed a facsimile of “Film Script 3,” by Yoko Ono: “Ask audience to cut the part of the image on the screen that they don’t like. Supply scissors.” That desk, he explained, a bit sheepishly, was devoted to new video-collage projects. Paul Anton Smith had kept culling movies for him, and Marclay kept being lured back to his Mac. “Since I returned from Japan, maybe I made two manga collages,” he said. “With the collages, I have to be in a certain state of mind, and I need to spread things around, for visual stimulus. But, with the computer, you can just click on these things and they’re all right there.”

Currently, Marclay explained, Smith was gathering footage of actors walking through doorways. Marclay had imagined turning the house of cinema into endless rooms. Doors would repeatedly open and close, as in a drawing-room farce, but there was no exit from this world of interiors. As with “The Clock,” the conceit was simple, but he already saw how it could yield layered drama. The work would be claustrophobic, dragging the viewer through a cinematic maze, but it would also capture the joy of discovery. “There’s a mystery behind a door,” Marclay said. “It’s just a beautiful moment. You don’t know where it’s gonna go.” He added, “Opening a door is a perfect metaphor for entering a new space—a new life.”

Marclay’s idea of “the hinge” seemed especially apt in this case. He set a rule: he would make a hinge to a new scene only when someone onscreen passed through a door. “Of course, that really makes it harder,” he said. Yet the strategy would create teasing suspense, as viewers waited for an actor to release them from a room.

Creating a seamless door transition was proving maddeningly difficult. The bodies on both sides of the door had to be moving with nearly identical momentum—otherwise, the illusion was shattered. The door had to swing the same way in both shots, and the angle of the camera had to be similar. “There’s so many different things that will make an edit point not work,” he said.

He showed me some “drafts.” Putting on black spectacles, he loaded Final Cut Pro. Film clips were arrayed onscreen like notes in a score. Marclay showed me various ways that he had tried to follow a clip of Klaus Kinski barrelling down a corridor and jumping up to knock down a door. One possibility was Naomi Watts, bursting through another door in her negligee, panicked. It worked reasonably well, but it wasn’t perfect—her feet, unlike Kinski’s, were planted on the ground. Now that people understood his method, Marclay said, “they are going to look for the mistakes—the less than perfect transitions.” The best match he’d found was a clip of Adam Sandler, barrelling midair through a hallway door while racing to kiss his new lover, Emily Watson. “That works nicely,” he said. The detective’s aggression had been transformed into a different form of male energy—romantic bravado.

The process of joining clips in Final Cut Pro, Marclay said, had suggested an audacious structural innovation. To find the best matches, he had made dozens of hinges featuring the same clips. One day, he realized that he could exploit this redundancy. The video would be a sinister looping mechanism. The viewer would occasionally be brought back to certain rooms, and these repeated clips would last just long enough to tantalize the viewer: “Wait, haven’t I seen this one?” Then the door would open onto, as Marclay put it, “a different world from what you had expected.” Marclay called the effect “loops with variations”—and he hoped that it would be delectably disorienting. This approach would echo the physical experience of being lost in a labyrinth, and create a different viewing experience from that of a linear video. “ ‘The Clock’ has a structure that I had to adapt to,” he said. “With the doors video, I’m creating my own structure.”

It was 5:30 P.M. “It’s time to go,” he said. White Cube was hosting a party to celebrate the opening of a huge new gallery—a converted paper warehouse in Bermondsey, near Tate Modern. On our way, we picked up his partner, Lydia Yee, who has a flinty intelligence. Her day had been hectic—she was preparing an exhibition on the Bauhaus—but she looked elegant, in a crisp tuxedo jacket. Though they have been together since 1991, she and Marclay had married just weeks earlier. The event had been low-key: two friends had accompanied them to Manhattan’s City Clerk’s office. I had learned of the nuptials only because Marclay had delayed a planned tour of his Brooklyn studio with the demurral “I can’t, actually, because I’m getting married.” Instead of wedding rings, Marclay and Yee exchanged orange friendship bracelets that would soon wear off.

The crush outside the party approached Bieberian proportions, with security guards bellowing at young men with thick eyewear and thicker beards. Jopling had turned the paper warehouse into a temple of ostentatious reserve: white walls, lacquered concrete floors. One wall held a thirty-foot-long Hirst “medicine cabinet”—mirrored shelving arrayed with pharmaceuticals—and Marclay asked a White Cube representative how much it was worth. When he was told, he said, “You could buy an Old Master for that kind of money.”

Many curators attended the party, and Marclay was besieged for requests to show “The Clock.” Minutes after someone from Lithuania talked him up, Sherri Geldin, of the Wexner Center, in Columbus, Ohio, approached.

“The museums who buy it get to go first,” Marclay said, apologetically. “There’s a waiting list.”

“But LACMA might let us borrow their copy,” Geldin said. “And you should remember that you once did a clock piece for us.” On a decorative scaffolding on the Wexner’s exterior, he’d affixed bell mechanisms that activated once an hour, turning the scaffolding into a giant noisemaker.

“Oh, yes,” Marclay said.

She drifted away, then returned two minutes later. “I just checked,” she said. “It was 1990, and it was called . . . ‘The Clock.’ So you need to finish what you started!”

“I’ve done ‘The Clock’ twice?” Marclay said, laughing. “Well, that proves that I’m too Swiss.”

We left Bermondsey, and headed to an after-party at Jopling’s house, in the West End. In a taxi, Marclay said, “None of my stuff is on the wall at any of the White Cubes right now, because my inventory is really low. I don’t flood the market.”

Yee added, “Also, your work tends not to come back onto the market. Museums buy it, and private collectors keep it.”

We spoke of a young artist, Jacob Kassay, a twenty-seven-year-old painter of silvery canvases, one of which was on display in Bermondsey. “It’s not always so good to be the overnight sensation,” Marclay said.

“Yes, you’re more like the tortoise,” Yee teased. “ ‘Slow and steady wins the race.’ ”

Marclay smiled. “You’ll see that my wife likes to insult me.”

The affectionate sparring continued. “She thinks I’m poorly dressed,” Marclay said at one point.

“You dress better now than when I met you,” Yee said.

I asked her when she had first seen “The Clock.” She said to Marclay, “You showed me only when you had fragments to show—it was one to one-ten, I think. You were nervous.”

“I usually don’t let her in the studio,” Marclay said. “She’s too smart. I’d never make anything.”

Jopling lives in a mansion formerly owned by one of the Stanhope earls. His dining room is a defining space of art-boom decadence: wainscoting panels have been outfitted with pastel canvases, by Damien Hirst, that are covered with the iridescent corpses of butterflies. Hirst, meticulously scruffed and wearing a snug Motörhead T-shirt, was in the dining room, amid trays of herbed cocktails and violet macaroons. He bellowed to Marclay, “Now we’re going have to make fucking big works for that goddam big gallery!”

“We’ll see,” Marclay said.

We ascended a curved staircase, and entered Jopling’s library. Amid the bookshelves was a bachelor-pad-size television, and on it, at a volume that could not be heard above the party’s roar, was a grainy, letterboxed copy of “The Clock.” Marclay winced. “I’m not happy about this,” he said. Curators at the party would see it, undercutting his claim that “The Clock” was never shown in suboptimal conditions. Marclay didn’t confront his patron, but he and Yee promptly went home.

Two nights later, we attended a party, at Whitechapel Gallery, for the Polish artist Wilhelm Sasnal. In an alcove, Marclay noticed a smaller exhibit dedicated to Mark Rothko. Marclay pointed at a framed memo that Rothko’s representatives had once sent the gallery: “Walls should be made considerably off-white with umber and warmed by a little red. If the walls are too white, they are always fighting against the pictures, which turn greenish . . .” Marclay gave Yee a wry look. “I feel vindicated,” he said. She touched his hand.

Marclay seemed determined not to become another White Cube product. In the following months, he kept advancing on the doors video, but he also returned to basics. He finished the Japanese scrolls—they looked terrific, screaming colors bound by rigid symmetries. For the Palais de Tokyo, in Paris, he began making seven windows printed with violent comic-book onomatopoeias; they suggested stained glass being smashed to pieces. And, in late November, he went to New York for a turntable performance with Otomo Yoshihide, a Tokyo sound artist. The concert was held at the Japan Society, near the U.N. Both men played two phonographs each, and their combined sound was sometimes so titanic that people walked out. Otomo fiddled with frowning concentration, but Marclay looked relaxed.

Wearing a blue sweatshirt, he ran his fingers over the phonograph stylus, as if he were playing the piano, lending percussive flair to the LP that he’d chosen—a string-heavy soundtrack. Then he fondled the needle, the sensual gesture creating an awful hissing sound. He played a jazz record covered with a masking-tape “X.” Then he tried out several new moves: he crumpled a paper record sleeve into a ball and tossed it onto the whirring vinyl, where it careered into the stylus like a bumper car. He slapped records against the side of the turntable, creating an earthquakey rumble. He and Otomo barely looked at each other, but by listening carefully they built a solid structure—interludes of call and response, a moment of peak intensity, a controlled fade to silence. As with “The Clock,” Marclay was making a big gesture from a series of small ones. He didn’t have time to select records carefully, but he made it work. When the performance was over, he looked as content as I’d ever seen him. “This is so different from when you’re making an object, and you present it and then walk away,” he said. “With music, it’s all about the moment—that very second.”