Amy Herzog, Gilles Deleuze: Becoming Cinema (2013)

Let me begin with a confession. I took the syllabus at its word, and was certain the writer I needed to follow was named Any Herzog. And for the first time in my life I wanted to be the mayor of Toronto so that I could hire her to repaint all the traffic signs in the city. Maybe she could just sign her own name. Instead of Stop, you would just read “Any.” Or “Anywhere.” Or: go anywhere you like.

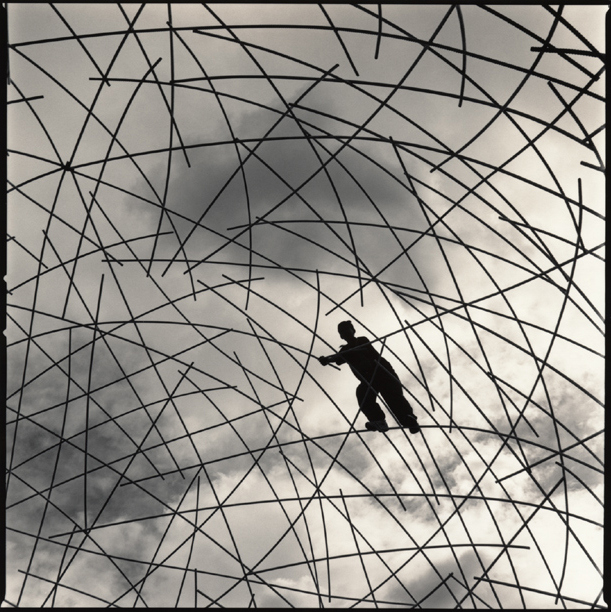

Resistance

So Amy Herzog is writing about this French guy, Gilles Deleuze. Gilles had a brother, an older brother, who was part of the French resistance during the second world war. His brother was caught by the Germans, and he died on a train, on the way to a concentration camp. I have to admit, I wondered as I read this: the fact that he died on the train, was he was lucky, or was he unlucky? Younger brother Gilles survives the war and becomes a radical philosopher, writer about art, shit disturber, often working with his psychoanalytic pal Felix. He had very bad lungs, and for the last 25 years of his life he was weak and had a hard time breathing. He was forced to live chained to an oxygen tank, and when he was 70, he threw himself out his apartment window in Paris and killed himself.

A dozen years before his death he writes a pair of books about the cinema. They’re called Cinema 1: The Movement Image and Cinema 2: The Time Image. While he gasps for breath in his apartment.

Style

I’d like to say a few words about his style. Because I think that as artists, and as people who care about art, or the art that is sometimes cinema, I think we’re interested in the news, the headline, the argument. But we’re also interested I think in how the argument is made. The form. The style. It’s not just a question of what is he saying, and then how is she taking that up, but how is he saying it, and how does she say it, after him?

Difficult

Gilles Deleuze’s words are so hard, so difficult. His writing has a lot of energy in it, you know, a lot of juice in it, and he uses that energy to throw up, to vomit up these words fogs. I think these dense fogs are really important to remember when speaking about him. And it’s also important for the people who love him, who want to work with him. Or to rework with him. There’s something erotic about that difficulty. In order to attract you, I’m going to put up a wall so that you can’t see me. In order for me to say yes to you, I have to say no, first. Have you ever met anyone like that before? Don’t worry, just give it time.

Why do his words have to be so damned hard? Words, language, are usually used to make a cut. The director likes to yell the word Cut. To signal the end of a scene. To signal the end of this table here, this surface which every atomic scientist in the world will tell you is actually infinite and without end, but when I use this word “table” I make a cut, and then the table ends right here. And it’s crisp and clear. There’s no ambiguity, no doubt. This is the table and this (raise arm) is not the table.

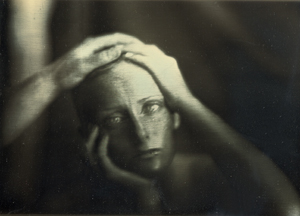

Fog

There’s something that hurts Deleuze about language when it’s used in this way. Maybe because he’s French. Maybe because he never stopped believing that the revolution he lived in Paris in 1968 could live on in his language – beneath the paving stone the bon mots – in the way he would use language. In the way that he invites you, insists that you, wrestles you to the ground and demands that you also use language in this new way. And so instead of language acting as a transparent window onto the thing it’s framing – this is my arm, this is the table – Deleuze creates a fog on the window. He presses his mouth up against the glass and he goes ahhhh. He creates a steam and a fog and the light bends until those simply clear words are not so clear any more. This creates a very particular kind of affect. It can be really frustrating for instance. Arouse anger for instance. Why can’t you just say what you’re saying? Or there might be boredom, alienation, distance. I’ve stopped feeling anything at all. Makes me sleepy.

Instead of a word like “table” instantly landing you on the object, Deleuze is hoping to sustain this travelling, he’s the whiny kid in the back of the car who never quite wants to get there, he wants to suspend this moment, he wants to hold onto this in-between place, in between a words and its referent, a little longer. And even when you get to the other side it leaves a taste in your mouth, because I think he’s trying to unsettle you, the reader, he’s trying to shake you, shake us, from some too familiar, possibly too distanced place. And even though he is writing about very specific ideas (that to be honest my far too small brain will be unable to parse and recount for you), it’s crucial to his project that the ideas arrive hovering in a bit of a cloud, they’re not quite all here, they carry with them the felt sense of being unsettled, a little unnameable, so that I can’t know for sure, not this, not you, not what I’m saying. Perhaps we could think of it as a kind of radical skepticism, and he hopes to use this radical skepticism to re-orient our relationships. Between you and me. The places between us. The way that we are together.

You’ve been so certain your whole life. Maybe you’ve grown tired of your perfect answers, and your perfect life. Maybe you’re tired of always knowing so much. If you read me, I could relieve you of the burden of all that knowing. Reading me, you won’t know more, you’ll know less, and most importantly, you’ll know differently. What if I could walk into this room, as if I’d never walked into this room before. What if I’d never seen your face before this moment? What if I’d never seen a face? And then how would you be looking if you could see a face that had never seen a face? Would you be able to have a face for the first time, or the last time?

The Movement Image

Cinema 1: The Movement Image. Amy says that Gilles says that there are two kinds of images, movement images and time images. What is a movement image? Gilles points to so-called classic Hollywood cinema and finds that everything in the movie is directed towards, is aimed towards, every instant of light and shadow is bent towards the progression of a story. Every detail rendered in close-up, every face burning with hope or shame, all of these can be laid along a single line that is clear and coherent and organized and progressive and that drives towards an ending and resolution. It’s as if everything in the room is fated, and meaningful. In psychoanalytic literature, I think we would call this paranoid, the sense that everything has meaning, everything is alive and it is speaking to me, and it is aimed in time like an arrow flying from a bow. Every action converges into a single point at the end of the movie. Bullseye, the end. And then you die. And then the movie dies.

The Time Image

Cinema 2: The Time Image. Amy says that Gilles says that around the end of the second world war, maybe, sometimes, but also at other times, there’s another kind of image produced by movies. The Time Image. What is time? According to Gilles it is the “interval” or the “whole.” This moment, and the whole clock which offers us an image, a picture, of every moment. The Time Image in movies features something Gilles calls “purely optical and sound situations.” Instead of being part of this grand design of a single story, instead of being a moment in this single thread that everything around you is also part of, the characters in these movies are cut from the umbilical cord of the mother, and they are wandering around lost. Wandering, unknowing, uncertain, unclear. These are cherished spaces for Deleuze. Why? Because they are places where something else can happen. They are spaces of possible transformation. If you already know what’s going to happen, if you walk into this room and you’ve already decided what this course is going to be like – and this is how anxiety works right, anxiety is always trying to get there first, it’s trying to lay a map over encounters that haven’t happened yet – if you already know, then you stop yourself from finding out what could have happened. Or what could be happening now. The thing many call “Conceptual Art” to me, feels like an art that is filled with anxiety. It’s very helpful to come up with a strategy when you want to stop feeling anything.

Bergson

According to Amy, and many others who have weighed in, Deleuze is copping a riff from Henri Bergson here. Bergson is a big brained French guy that lived in the last part of the 19th century, and early part of the 20th century. Spent nearly his whole life in school, studying, then teaching. At the end of his life, as an old man, very sick, many had forgotten him, he’s retired, and his beloved France was occupied by the Germans, by a Vichy Government, a proxy Nazi government who said, hey Henri, you’ve been an important person, a respectable guy, listen, we don’t have to think about you as a Jew. We don’t have to treat you as a Jew. And he said, because he wanted to express solidarity with the Jews who were suffering and dying across Europe, he said no, I’m a Jew.

So let’s roll back a little bit. I’m just offering Wikipedia riffs, I don’t know anything about any of this but here goes. Bergson is interested in what is happening in this moment. He believes that philosophy, the practice of philosophy, is about a carefully noted embodiment of what is happening in this moment. You know the French have this tradition of philosophers who just lie in bed and have beautiful dreams and they write all those flowery gorgeous abstractions. But Bergson wrote about what it meant to be here, here, in this moment, in this room, in present experience. And one thing you notice when you’re here, in present experience, is that you can’t really say where you stop and someone else begins. The illusion is, the dominant cultural habit pattern is, that the table is over there, and I’m over here. I’m the subject and it is the object. But every atomic scientist will tell us that when they look at the table through the electron microscope they are changing the table by looking at it, and they are being changed. In other words, we are always part of what we see. Before there were atomic scientists there was Bergson.

Table

“Lay your hand down on a wooden table. With as little conscious thinking as possible, allow adjectives to rise that describe what you feel. Perhaps hard, smooth, grained, supportive, resistant.” Now ask yourself: are any of the words you used to describe the table not also descriptions of your hand, but in shadow-form. “Hard” as compared to what? Your hand. “Smooth” in relation to what? Your hand. You took on the task of describing your world through your hand contact. You feel as though you became aware of the table. But, considered closely, your names for the table actually described both you and the table equally, and in relationship. The table gave you an awareness of yourself.” (Threads of Yoga by Matthew Remski pg. 57)

In fact, I think Bergson would argue, this is what we’re doing all the time, we’re changing each other whenever we are interacting, interfacing.

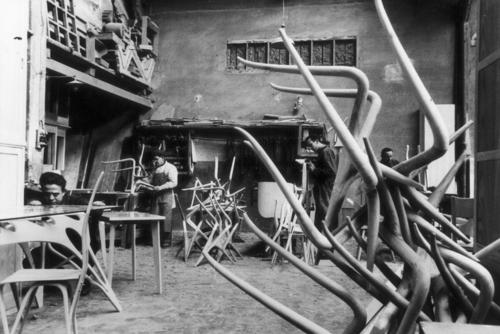

Furniture

In my culture they’ve done this really strange thing, they’ve built and they keep building the same kind of objects over and over, call it a terrible compulsion, you see they’ve built this thing called furniture. I think furniture’s been designed so that I don’t feel this (tap ground) any more, my connection with this ground feels a bit faraway and abstract. And also the furniture is like my skeleton except it lives outside of me, and what my skeleton does is that it holds me up. What my chair skeleton does is that it lifts me away from the ground, which is dirty and disgusting and base, and it holds me up, it supports me, and what this is really helpful for is that it stops me from feeling. It stops me from feeling this, which is also a little dirty, and disgusting and base. Don’t you think? And I love the way my chair does that for me. Don’t you love that?

When you live amongst people that don’t have so much money, and they have to hold themselves up by themselves, because they can’t afford to pay for these chair skeletons, you start noticing that when you hold yourself up, you start feeling this here, the skin bag, the meat. Or as Bergson might say it, you find yourself in a place where you might begin the practice of philosophy.

Movies

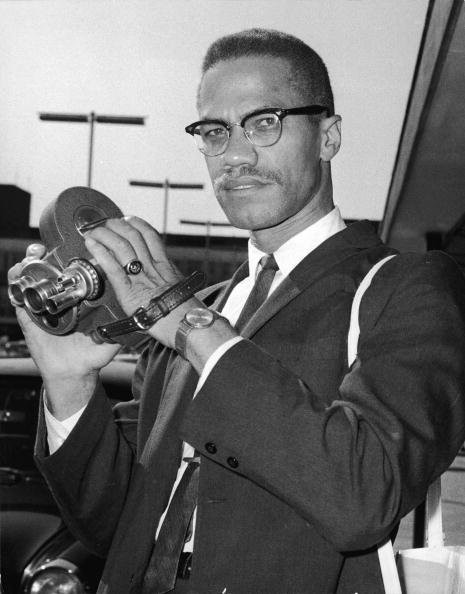

So to run back to Gilles Deleuze, who is wheezing and struggling to breathe in his apartment. He’s looking at the movies, ok? And he is writing about the movies not as pictures that show something other places, faraway events. Movies are not a language for him. And he’s not even so interested in the way that movies reverse code their viewers, oh I see large bottle of coca cola, I want to drink large bottle of coca cola. Instead Gilles runs his long fingernails – have you ever seen late interviews with this guy, he had really long fingernails – he would run his fingernails between the movies and the viewers, and he can’t find any space between them. Just like we explored with the table and your hand. Your hand is part of that table, and the table is part of that hand. And the movies aren’t over there, there’s not a subject and an object, a figure and a ground, that was the old world baby, that was before 1968. But after we lifted the paving stones and found the beach, we saw that the cinema was inviting us, was involving us in a series of relationships, it’s the new wave, and the relationships that are most important for Deleuze of course are the ones where we are wandering, and lost and confused, where we have too many words, or too few words, where shadows are becoming light, where humans are becoming animals, which we are by the way. And what is important is that these relationships are occurring in this moment, we are plunged into, we are immersed, in this set of relationships that we are a part of. And just like, you know, how certain people in your life make you funnier than you are. And just like, you know, how certain people in your life make you smaller than you are. Or smarter. What kind of relationships are you part of, have you enrolled at this university to be part of. All this of course has something to do with desire. If only I could be with someone who could make me feel small, then my love could be so big. Desire is very important for Deleuze of course, if we are if we are always a part of what we are looking at, if we are always a part of each other, if there is no myself over here and yourself over there, it means that fundamentally we are always in relationship. And part of what is singing in that relationship has something to do with desire, and for Deleuze, I think, this question of desire is also the question of how are we going to make the revolution together, how are we going to be free together. I mean the revolution of who you think you are, and what this state we call the state could be – idle no more – if we don’t have desire how can we make the revolution, or become the revolution?

Intuition

Amy says, or would like to underline that Gilles says, is that in these new relationships is that when you have lost your way, when you are staggered and confused, one of the most important qualities you have is: intuition. Intuition, it’s a kind of knowing, isn’t it? But it’s not a calculation, it’s not something you can download as an app, or order at the drive-through. Just fill it up ok, I’ll take twelve quarts of intuition juice. It’s a kind of thinking that comes before or after thinking, and Deleuze says that in the cinema, the time image is like a gym where we’re going to work on our intuition muscles. we’re going to make them shiny and big. And I think that has something to do with trust, with trusting this, this place, this body, which calls us back to this moment, because this is where intuition comes from right? This ocean of sensation, this body is receiving so much data at every moment, every moment, and intuition is some way of translating or transforming these sensations, which are happening in this moment, in this moment when we are practicing philosophy, when we are alive to the cinema, when we are the cinema. When we become the cinema, the time image is us, we have a new relationship to our intuition. We’ve stopped trying to get somewhere. We’ve left the reliable stories of our lives behind, it’s as if my life wasn’t a set of stories I could lay out for the dinner guests, it’s as if my cherished set of stories, my cherished views of who I am, can finally be relinquished, and let go of. All so that I could be here, and feel my feelings, without having to decide good or bad. Amy likes to use this kind of language. She calls it the “zone of indeterminacy which lies between perception and action.” If that’s what turns it for you, great.

Feminism

What’s important here, in part, is that Amy Herzog would like to claim some of this real estate of uncertainty, she would like to take some of that Deleuze fog, and press it into the service of a feminist project. Because as a woman, as someone who isn’t white and male, as someone who doesn’t sit naturally at the head of the table, there are a thousand power relations that need to be redressed. Pay equity, body image friezes, glass ceilings that need to be broken. For instance. She’s interested in cinema as a site of production, instead of a place of reproduction. It’s not a frame where I can take my place as a minion in the society of spectacle and lie passive and inert and overstuffed while someone else does all the work. She aims, as she quotes from Deleuze again, “to get things moving.” And part of what I think she would like to move is the project of feminism itself, which has been so important in rewriting the not so grand narratives of the past. Part of this work has been necessarily to fix a place for women (as, for instance, the suffragettes did so necessarily in working to secure a place for women at the ballot box – it wasn’t until after the first world war that women were allowed to vote in Canada, by the way). But now, she seems to be saying, and in addition, she would like to consider the collection of forces that collude, that work together, to create women’s identities. And set them into motion, into some always becoming motion. I think she is turning towards the mist on the window, and the window itself, to hold out this hope for a new kind of movement, to get things moving in some still unnameable and more than ever necessary way.