Anna Gronau: The Dead Are Not Powerless (an interview) (2000)

Born in Montreal in 1951, Anna Gronau moved as a teenager to Toronto, where she became a central figure in the city’s turbulent fringe-film scene. Between 1980 and 1982 Gronau was Director/Programmer of the Funnel Experimental Film Theatre, and from 1983 to 1985 worked as video distribution manager at Art Metropole. She has written and lectured tirelessly on feminism and the avant-garde, touring work and championing marginal expression. She also led the charge against the intrusions of the Ontario Censor Board. Rallies, protests, and politicking were capped by many hours in the courtroom interrogating government agents, exposing the capricious judgments and ambiguous standards applied to motion pictures large and small. While she was helping so many others, she was also quietly developing a body of work all her own. She appears in all of her early work, though it is the structure of cognition rather than the narrating of personal experience that impels her concern. The solitude that haunts her work is narrated in a succession of subtle and painful autobiographical moments — the ending of a relationship, the death of a friend’s child. Many of her films suggest ways in which the self can interact with an outside world, negotiating the divide between inside and out, between self and Other. Her later work has taken up politics in a different register, often using dramatic elements to unwrap the layers of history that occlude relations in the present. Her work asks us to remember, while showing us how.

AG: I got involved in film by coincidence. Back in high school, in Hamilton, I had a friend at McMaster University. We used to hang out at the Film Board there. It was a place where some ambitious young filmmakers — some of whom went on to be famous — were watching a lot of movies and planning their first films. I saw my very first experimental film there, if you don’t count the Norman McLaren films we saw as kids. Then, when I went to the Ontario College of Art, I met Keith Lock and Jim Anderson, who were studying film at York University. We all ended up living in a communal house around the time the first Toronto Filmmakers’ Co-op [a non-commercial production/post-production facility] and the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre were being set up. Jim and Keith and others in our house were very involved. While I was studying painting and sculpture at art school the whole notion of “avant-garde” caught my interest. I understood it at the time in its relation to the military idea of an “advance guard” — leading the way. My belief as a young art student was that avant-garde art would be taken up by people at large. I never thought of art as a permanently separated cultural activity. The idea that there were avant-garde films seemed completely natural to me. This was around 1969/1970. The counter-culture was still something people believed in. There was a lot of performance going on and anti-object art was big at the time. Idealistically, I believed that the ghettoized, even despised, status of avant-garde film was only temporary. As I remember it, avant-garde film wasn’t much different from alternative rock music in terms of the value that I and the people I knew felt it had. We saw all kinds of “youth culture” as being on the cutting edge — and leading somewhere. Otherwise, I don’t think we would have been interested. Of course, as we know now, rock music did “go somewhere” — and avant-garde film went somewhere far less dazzling! Still, I had high hopes for leading-edge filmmaking, although at the time I didn’t consider the problems of the notion of avant-garde, such as the way it assumes leadership and hierarchy.

The first film I made was for school, and Keith helped me. It was a “structural” film called Inside Out. I was living in an old farmhouse with a big picture window in the kitchen that overlooked an orchard. I set the camera on a tripod half an hour before sunset, turned on the kitchen lights, and filmed a kind of time-lapse out the window. I exposed a few seconds every couple of minutes. As the sun went down, the window darkened, revealing the reflection of me and the camera. The film was about ten minutes long, but I’m afraid it’s lost to posterity now. [laughs]

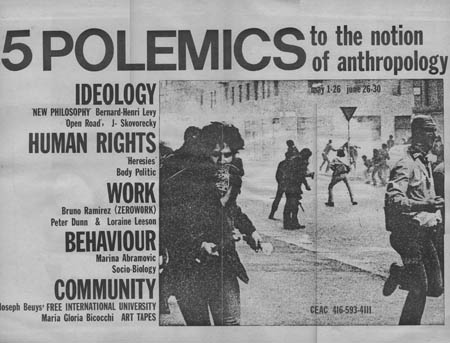

After I graduated, I helped Keith and Jim with their films and went to screenings and meetings of the Film Co-op, but I hadn’t had any technical instruction at OCA so I didn’t have the confidence to try making my own films. I lost touch with film for a while, and then in the late seventies, Jim Anderson, his brother Dave, and Keith started holding screenings at a studio at the corner of Adelaide and John Streets. The building belonged to a company called Freud Signs! The screenings helped me realize that I still wanted to make films. Then I heard about a filmmaking workshop at a new organization called CEAC, the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication. The workshop was associated with the Funnel, a program run by CEAC, which had been holding biweekly experimental film screenings just down the street from Freud Signs. The Funnel was in the process of setting itself up as an independent organization and that’s when I became involved. I felt it could help me both make films and see a lot of work. The first screening I attended featured films by James Benning. His approach to filmmaking showed the sensibility of a painter and poet, so with my art background, it began to look like the Funnel would be a good place to be.

MH: Can you describe CEAC?

AG: It released publications, staged performances, provided video access, and hosted conferences. CEAC also ran an educational program which included the filmmaking workshops I attended.

MH: Why did the Funnel separate from CEAC? Was it a difficult transition?

AG: Separation started before I became involved, but I think the idea initially was that the Funnel had a strong mandate and could likely function well on its own — get its own funding and so on. But many things started to happen at once. The Toronto Filmmakers’ Co-op was on the verge of bankruptcy. As I was told, it had lost its “alternative” approach and was being used as a low-cost quasi-commercial facility and was accumulating untenable debts. The Canada Council asked members of the independent film community to get involved and try to save the Co-op. A number of people who did so were also trying to help the Funnel get on its feet. The Co-op turned out to be in worse shape than we’d thought and eventually we had to declare bankruptcy and close it. But this wasn’t a unanimous decision. I think some filmmakers felt that the new board was simply trying to kill the Co-op and grab its funding. To the best of my knowledge, this wasn’t the case, but it made for a lot of tension. Meanwhile, CEAC began to take a radical militaristic, guerrilla- type stand. They were starting to say that art wasn’t enough — to change society you have to go out and shoot politicians. [laughs] This became a political hot potato when the Toronto Sun got hold of a copy of CEAC’s newsletter, Strike. The cover showed a picture of Italian premier Aldo Moro, recently murdered by a political terrorist group called the Red Brigade. CEAC’s editorial voiced support for the Red Brigade. The Sun declared its outrage about this on its front page, and all public monies to CEAC were quickly stopped. This really split the arts community. A number of arts organizations openly condemned CEAC. The Funnel was in the strange position of already trying to separate from CEAC. When CEAC demanded a letter of support from the Funnel, they were refused. In retrospect, that seems like it may have been cowardly, but CEAC wasn’t behaving very honourably, either. For a while there was a feeling that CEAC might try to seize the Funnel’s “assets.” In the end, we stored all the stuff — some chairs and tables and a projector — in someone’s basement and searched for another home for the new and separate Funnel. So, yes, it was a difficult breakup.

MH: How did the Funnel’s theatre get built?

AG: We finally found a location on King Street East. Within a month, using only volunteer labour, we turned a raw warehouse space into a one-hundred-seat theatre with a projection booth and an office space. We opened in January 1977.

MH: How many volunteers were there?

AG: About twenty. The “core” membership was always around twenty. Over the years people came and went, but the figure was always about the same.

MH: Was the initial idea to build a theatre for fringe film?

AG: Different people had different ideas. Ross McLaren, who had been involved while the Funnel was at CEAC, always wanted an equipment co-op. But that wasn’t feasible politically or legally because the Toronto Film Co-op was going bankrupt. You can’t declare bankruptcy in one organization and then start another that does the same thing. Some members felt from the start that the Funnel should be a cinematheque, and that’s what it was initially. But after a while we started to get some production equipment — at first only super-8 cameras — that was clearly outside of the old Co-op’s mandate. Later on, we also got post-production sound gear and 16mm cameras. We tried to set up an integrated and complementary facility in production and exhibition. For example, we purchased a good super-8 projector which could also be used to record sound in sync with the image as it was projected.

MH: How was it decided what kind of work would be shown?

AG: In the very beginning it was a mixture, based mainly on what we could afford: more established Canadian experimental filmmakers like David Rimmer and Mike Snow and Joyce Wieland, and younger local filmmakers doing personal, low-budget filmmaking. By the time I started working at the Funnel, there was a little publication called the Filmmaker’s Newsletter that came out of Minneapolis. They announced new films and screenings and screening facilities, and this created a circuit so experimental filmmakers could take their new works on the road. There was never any money. The Funnel had grants, which was more than some groups had, and we only paid an honorarium that may have just covered plane fare. But there was an international community that was excited to see and show work. We used to show experimental or avant-garde work from all over the world. There was a wide range; some films were very conceptual, some were highly politicized, others more diaristic. It was an exciting immersion. We held two different screenings a week, usually with the filmmaker present to answer questions and discuss her/his work. Frequently, our guests were from out of town or from another country.

MH: Did a lot of people come to screenings?

AG: There were a few devotees who came to everything. There were times when there’d be only ten people in the audience and others when we turned people away. It depended on the profile of the filmmaker. But we worked hard to spread the word. We made up little Xerox posters every few weeks and plastered them on downtown hoardings. That was better publicity in those days because not many people were doing it. Eventually we sold memberships and mailed out calendars every couple of months. Occasionally we got a write-up in one of the daily newspapers or in an art periodical, but that didn’t happen often. The best and worst publicity we got — it was inevitable that this would come up in a discussion of the Funnel — was from the Ontario Censor Board. I say this because the film censors made our lives extremely difficult. But the fact that we resisted their interventions resulted in a lot of media attention and the Funnel became much better known. At first, the Ontario Censor Board insisted that we send them every film we wanted to show a week in advance of the screening so they could classify it and mark the print with an embossed stamp. They also wanted us to advertise the film’s “rating.” Even if we hadn’t found the whole idea abhorrent ethically, it would have been impossible solely in practical terms. Filmmakers usually arrived with their work from out of town just a few hours before their screening. We protested and got all sorts of high-profile supporters to speak on our behalf, but the Censor Board refused to give up their right to preview and “rate” — and potentially ban from screening — all films we showed. For a while they would even send someone down to the Funnel to watch films on our premises before the screening. It was ridiculous. But resistance began to grow because the Censor Board, having more or less stumbled upon the Funnel (as far as we could tell) suddenly realized they’d opened up a hornets’ nest. I don’t think they had any idea of all the independent film and video activity that was going on in Ontario. David Poole from Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre, Cyndra McDowell from Canadian Artists’ Representation, and I eventually became the board of a small organization that took on the Censor Board through the courts. Our group was called the Ontario Film and Video Appreciation Society. We took the offensive, and charged the Censor Board with being unconstitutional under the Charter of Rights. The Canadian Criminal Code stated that if material was made public and the public complained, charges could be laid and judged according to community standards. But this was a hired board whose job was to decide for the public in advance what it could and couldn’t see. We argued that this prior censorship was unconstitutional. We had some legal victories, although we were obviously the underdog in terms of resources. I think we won mainly in the sense that we revealed the ludicrous nature of many aspects of the current legislation. But it was an ongoing struggle. By the time I left the Funnel, we had won a small amount of leeway: the Censors required only that we submit a written description of films we planned to screen. They still retained the right to ban a film, however.

MH: Tell me about the Open Screenings.

AG: These started when the Funnel was still part of CEAC. The idea was that once a month anyone could bring her/his film and it would be screened publicly. Films ranged from home movies to student films to offbeat stuff that you might imagine strange people had obsessed over in basement editing dens. To tell you the truth, I liked the idea of Open Screenings better than the reality of them. They were often tedious and boring. Then the Censor Board made open screenings illegal because people who just showed up with their films couldn’t submit their work to the Board before they showed them. We saw this as a real affront to the notion of freedom of expression.

MH: Did that affect public opinion about the Censor Board?

AG: I think it contributed to making the censorship laws look silly, but actually, I think it was the huge number of run-ins with the arts community that gradually undermined their credibility. The last straw was when they started to mess with the Toronto International Film Festival. That was truly politically embarrassing. The Censor Board had already lost a couple of times in court, but it was not until they found themselves in a standoff with the Film Festival that they started making accommodations. Unfortunately, not much has changed. We still have a Censor Board, and, just like before, the law is full of loopholes. Our argument had always been that the law was wrong and dangerous, and the fact that it might not be enforced to the extent of its full insanity didn’t make things any better. The law still gives the government power to infringe extensively on freedom of expression if and when they are so inclined. Today most “fringe” media is exhibited in an underground setting — without the Censor Board’s knowledge. We’re back where we started.

MH: Was there a common ideal at the Funnel?

AG: The idea of community was the strongest link. But in the end, this ideal devolved into an us-versus-them mentalitywhich entrenched marginality for its own sake. There was always a reluctance to discuss art issues in a very deep way. One reason may have been that many members were from working-class backgrounds. Intellectual posturing and intimidation has often been a way to keep working-class people “in their place,” so I think there was a lot of wariness about any talk that smacked of academicism. Another reason was probably a fear of discussions that could exacerbate our differences and cause rifts in our small community. But ultimately the inability to deal with difference was what enabled that garrison mentality to take hold. The group was pressured from within because non-white, women, and lesbian and gay members were in a minority, and there was resentment and defensiveness about that. There was pressure from outside, too. We were the only place around showing non-narrative, independently made films, and a lot of people felt that the organization should be for them. It wasn’t like the visual arts, where you may get turned down by one gallery, but there’s another that would love to show your work. I think we hurt some people’s feelings and I regret that. But anyhow, that’s dwelling on the negative. On the bright side, there may not have been an articulated “ideal,” but there was great excitement and enthusiasm surrounding and within the Funnel for a while. Lots of outstanding work from all over the world was screened, including a lot of locally made films. There was a feeling for a time that something important was happening. We had a gallery for visual art there, for example, which made an important link with that community. Younger people, just coming out of film school, were encouraged to pursue filmmaking because of the sense that a vibrant independent film scene existed at the Funnel. When I was doing the programming I did have a pretty clear idea of what I wanted to achieve. That was certainly an “ideal.” I was interested in film as a kind of radical area between what was cutting edge and daring about visual art and what was powerful about the movies. I liked the way visual art was inventive in its uses of materials and its incorporation of unexpected elements in order to say important things. And I liked the way that movies get at you emotionally with their “realism.” I still had a lot of belief in the idea of the avant-garde. I was interested in the ideals of some of the new feminist films being made at the time, the “New Talkies” they were called, and I did some programming using and referring to them. But frankly, I felt that some of them were better as theories than as films. However, it wasn’t enough for the organization to represent the ideals of one or two people. As an organization, the Funnel’s identity was too marginalized. To most people involved it rode on some hazy idea of being “alternative.” I see now that just wasn’t enough.

MH: The Funnel required an incredibly committed membership to ensure the organization could fulfill its ambitious program. There was a belief…

AG: Yes, there was. It wasn’t often articulated, however. Part of the belief was in a general sense of community, it was something to belong to. The Funnel had very little money with which it sponsored extensive activity and programming. Anything it accomplished it did on the backs of staff and volunteers who worked so fucking hard, myself included. When I was on staff in the early eighties my pay was $7,000 a year and I put in long hours — usually every day of the week. It was our dedication that allowed the place to exist. But it wasn’t sustainable. Even without the more philosophical and political difficulties it was grappling with, the Funnel just didn’t have the economic base to go on like that. It closed down after I had left it, so I don’t know all the final circumstances. From what I could see, it seemed to lose steam and slowly disintegrate.

MH: What has it meant not having it around?

AG: For me personally, it was a relief. When I stopped being the Director/Programmer I joined the Board for a while, but already it felt like the organization was in a rut. The same arguments and difficulties came up again and again. So I left altogether. When it finally closed a few years later, I was glad. In its last years it seemed to be digging itself deeper into a mess and I didn’t want that to be all that anyone remembered about it. In a bigger sense, its demise made room for LIFT and Pleasure Dome to develop.

MH: Okay, so let’s get back to your own work. How did Wound Close (8 min super-8 1982) begin?

AG: Well, like most of my films, it started as one thing and gradually turned into something else. In the late 1970s, my best friend Eleanor gave birth prematurely to twin girls. One baby, Ona, died shortly after birth. The surviving twin, Rafiki, died tragically and unexpectedly at the age of four. I’d originally planned to make a birth film, but when the babies were born in such bad circumstances I couldn’t bring myself to do it. I did, however, record a conversation between Eleanor and myself. The only image I shot was of Rafi in her hospital incubator. I just held onto the footage and the recording. When Rafi died it was a terrible, terrible thing. I felt then that perhaps I should have filmed the birth. At any rate, I decided I wanted to make a film as a memorial to Ona and Rafiki, and a tribute to Eleanor.

MH: There are alternating close-ups of you and your friend, lit to show half your faces, as if you’re complementary halves. It reminded me of Bergman’s Persona, this marriage of parts.

AG: I wanted to show how close we are, and also to reference the two children. I edited the film symmetrically, like a palindrome, with one central image and matching sorts of images on either side of that centre, all the same length. Using that kind of a structure was an attempt to find a form for something rather inexpressible. That film is the most personal one I’ve ever made. It uses images that probably have meaning only for Eleanor and me. For instance, the centre section was made from short takes of a drawing that Rafi made. Another shot was of a horrible artificial flower arrangement encased in a glass egg. The hospital where Rafi died sent it to Eleanor as a condolence. It was our belief that their negligence contributed to her death. I filmed Eleanor smashing that glass egg against the brick wall of the hospital. I never expected anyone else to know what it meant. I thought there was a chance that a trace of the emotions might come through. And I do think that some of the other images I chose might have an archetypal resonance — images of snakes, and a lake in winter. But this particular film was primarily personal in its intent.

MH: There’s an openness of interpretation occasioned by much of your work.

AG: That’s interesting. I hope that my work will point to some paradoxical and ambiguous places — and in doing so remind me, and the viewer, that we do well to resist hierarchies and situations in which one person’s understanding is the law, the only truth. I think the “openness of interpretation” doesn’t necessarily mean it could be about anything at all, but rather that within its parameters there’s room to move and breathe. That room, that space, is important to me.

MH: Usually movies unify their audiences through identification. But in artists’ films the reverse is often true: some hate them while others rave on. There’s a large part the viewer plays in the construction of meaning within these films, but that also alienates a lot of people from fringe work. There doesn’t seem enough to be able to hang on to because the terms of the usual theatre experience, the terms that unify the whole body of the audience, are no longer there.

AG: I agree. That’s why I especially like films that both grip you the way the movies do and let you think and breathe and reflect.

MH: How was the critical response to your work, or to work made at the Funnel?

AG: Well, there was just about no critical response. Eventually I found the situation so ridiculous I decided to stop calling my films “experimental.”

MH: What was ridiculous about it?

AG: Well, during the time when I was at the Funnel, we were making, showing, and distributing films, as well as being the audience and the reviewers, too. That’s ludicrous. But it’s the situation that has existed for experimental film — and video art, in a lot of ways — for a long time. It’s come to be expected that these art forms comprise a more or less self-sustaining, closed world.

MH: Regards (31 min 1983) seems a departure from some of your earlier, shorter work.

AG: Regards was a more serious project, a bigger commitment. It was shot in 16mm and was, if not scripted, at least well-planned before I shot it. Regards dealt with perception, particularly vision, and other systems of knowing. I wanted to take these systems to such extremes they would fall apart. The idea was about certainty and knowledge being provisional tools at best, and ones which, when pushed to the limit, point us toward places that are uncertain and unknown.

MH: For example?

AG: There’s a sentence in the film that appears as a subtitle: “What is it that makes breakfast so different from other meals?” I recorded five people who didn’t speak much French trying to translate that sentence. The result is five awkward translations heard on the soundtrack. I was attempting to show that middle point between these two systems. The place where translating occurs. There’s a way to say the phrase in English and in French, but there’s also this in-between place where the meaning exists without really being one or the other.

MH: And this place between, is that the image?

AG: I wouldn’t identify it solely with the image either, although it arises in relation to certain images. For example, while the different voices ask the question about breakfast, the image is of a woman eating an egg. It’s a looped shot, so she seems to be eating endlessly — far more than the contents of a single hard-boiled egg would require, and there’s an arrow following her hand movements. A subtitle at the bottom of the screen reads, “What is it?” which seems to refer to the hand the arrow points to. But after a while, the arrow begins to ramble aimlessly around the screen. You think, “What is what?” Not just “What’s the answer?” but “What’s the question?” A space opens up between the sign and its referent. To me, this temporary release of the hold between experience and interpretation allows for a different kind of relatedness, or maybe an interrelatedness, to be suggested.

MH: What’s the sequence that follows — is that the elderly woman reading from Bataille’s Story of the Eye?

AG: Yes. She’s holding an occluder, which looks like a round spoon with a long handle, used commonly in eye tests to cover one eye while reading charts. The woman reads to herself with one eye covered, and then aloud with the other eye covered. For most of us, reading with one eye is more or less the same as reading with the other. The exception is the case of so-called “split-brain” patients. The passage from Bataille she reads is about how keeping certain objects is the only way the author can remember. His other attempts to remember are blinded by the sun, his memory turns into a “vision of solar deliquescence.” I thought it was interesting that light may obscure rather than help vision, and that the writer claims he can’t trust what he sees in order to remember. I was also interested in the difference between looking at a text as something you can read and seeing it as an object.

MH: And how does it end?

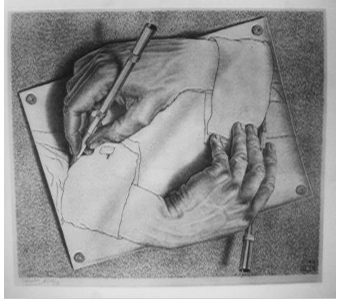

AG: The final sequence involves a hand drawing a picture while the picture is superimposed over the portrayed object. But the object is also a portrayal — it’s a model of a theatre proscenium. So there is a multiple layering of representations with no final or absolute “original” they can all refer back to.

MH: How are the different sequences connected?

AG: There’s always a lot of invention that goes into reconstructing one’s intentions from so long ago. Sometimes I think that I was concerned very much with negativity, the famed negativity of the avant-garde. I wanted to push its destruction of meaning so that the film would be negative about negativity itself. What I think I had in mind was to have an anti-structure — things connect, but they don’t add up or pay off. But if you relax, it could be fun to watch all these little games the film contains going on and falling apart and then reappearing in a different way somewhere else. I was thinking about the word “regard” — meaning respect, esteem, acknowledgement, but with visual overtones. Like when we say “I see.” It isn’t the same as “I understand.” It isn’t as masterful as understanding. It’s more of an acknowledgement.

MH: What’s Mary Mary (60 min 1989) about?

AG: The “story” is about a filmmaker named Mary who goes through a period of intense withdrawal inside her home and gradually lets the outside world in.

MH: You worked on the film a long time.

AG: Yes. Partly because I work slowly and partly because I kept running out of money and not being able to get more. It began in 1985 and wasn’t finished until 1989.

MH: Mary Mary quotes a lot from The Secret Garden. What’s The Secret Garden about?

AG: It’s an English children’s book from around the turn of the century. It’s about an orphaned girl who goes to live at her uncle’s mysterious manor on the Yorkshire heath. She discovers that her uncle’s son, her cousin, has been crippled from birth and locked away, and no one wants to talk about him. It turns out that the boy’s mother died when he was born, and his father — a “poor hunchback” — was so grief-stricken that he abandoned his home and his son. Mary soon discovers the key to the secret garden that was lost when the mother died. She teaches her little cousin to walk, and becomes a revitalizing force for the household. The book is objectionable on a great many levels from a contemporary perspective, but elements of the story appear in lots of children’s tales. It has roots in fairy tales like “Sleeping Beauty,” where a whole castle lies dormant after the princess’s “death” until there’s a rebirth. There are similarities to “Beauty and the Beast” as well, because the mother who died was a beautiful young girl, while her husband was hunchbacked (i.e., monstrous or beast-like). The garden coming to life also relates to the myth of Demeter and Persephone. I had a great time discovering all these interconnecting bits and pieces of mythical stories. I was amazed to find ancient tales about the marriage of a human woman to a not-quite-human bridegroom. The earliest were pre-Greek, yet remnants of them are apparently still acted out in folk rituals in some parts of the world. I hoped I could weave some nice seamless form out of all the tidbits I had unearthed. Eventually I realized that the only thing I could do was embrace the contradictions of these many stories and incorporate contradiction itself into the film. For instance, in the opening scene, the camera glides up a laneway toward a house as the voice-over describes Mary’s approach to her new home. But gradually it becomes apparent that the voice is describing a different house than the one onscreen. Things like that happen repeatedly in the film.

MH: The film feels like a psychodrama in its use of surreal imagery, with M. always in bed, filled with dreams.

AG: It focuses on the psyche, but I wouldn’t call it a psychodrama exactly. As I understand it, psychodrama starts with an understanding of the mind as a cohesive but stratified whole, so while there is material that is not conscious, there’s always a centre, a “self” that’s fairly stable and acts as a central reference point. In Mary Mary, though, identity and self are much more troubled constructions. For instance, the film’s protagonist, “M.” or “Mary,” is doubled in various ways. There’s the old story about the “doppelgänger,” that when you meet your double you disappear. And I think that’s true to the extent that when the myth of our integrity as unique and separate beings is threatened it can seem that non-existence, annihilation even, is just a step away. Nevertheless, I think the emotional appeal of the film is the lure which that deeper ultimate meaningfulness always seems to hold out. It’s hypnotic. En-“trancing,” even. You feel like you’re discovering so many clues there must be a meaning, even if you don’t know what it is. I suspect that’s how we build our sense of a self anyway, from a surfeit of clues.

MH: Can you talk about the telephone calls? They run throughout the film as a recurring motif that disturbs M.’s sleeping solitude. The first one is from a guy, the second from an arts council, the third for a censorship rally, and then you call as director, or friend…

AG: …Or who-knows-what, because M. turns the answering machine off before that caller has a chance to say anything much the audience can hear. The calls fill us in on aspects of M.’s life, but they also show how her identity is formed by people and events outside herself. And outside of the film, actually. I find the off-screen space of phone calls in movies really interesting because it is so utterly virtual. In most scenes it’s unclear whether M. hears the calls or not. In fact, for most of the film, it seems as if nothing gets beneath her surface. It’s like she has no interior. We see dirty dishes, but we never see her eat. The phone calls set up M.’s relationship with the world, but keep it distant at the same time. So when she finally picks up the phone, it’s almost a shock. That scene is the first time the curtains in her room are open, so we can see something outside. It’s the beginning of her movement away from her interior world.

MH: The scene where she watches television is strange because you use the music that started the film as the music that’s supposedly coming from the TV. It’s as if the film is starting over — that we’ll again see all of the events leading up to this place on the couch. What is it that she’s watching exactly?

AG: Well, she turns on the TV, but she’s looking at the floor. We can’t see the screen and she’s not looking at it. So it’s like an empty space, more of that off-screen virtual space.

MH: Then she picks up the Polaroid camera and begins taking pictures of herself …

AG: Once again there’s a discontinuity, a gap. She’s photographing herself in the dark, but she can’t see the photographs or what she’s photographing. We see her holding the camera. We see an approximation of the picture because of the flash. I intended it as a reminder that our place as viewers entails certain privileges, but also certain limitations.

MH: What does it mean when M. says, “Never dabble in autobiography unless you want a perfect world that perfectly excludes you”?

AG: One of the things the film tries to deal with is the urge to find perfection, original truth, the first and authentic instance of something. M. makes that remark. She’s making a film about herself — presumably to find or show the truth about herself. But the more detailed and realistic or “perfect” any story becomes, the more it hides the mess and truth of its making, and the more it functions as a circumscribed world with its own rules — in other words, a world quite separate from the world it “represents.”

MH: At different points in the film, numbered lists of titles appear superimposed on the image. In several titles there’s reference made to Indian mythologies and the relation of Native people to the land — and this seems to connect to the landscapes we see in the film that surround the house by the bay, the setting of the film. It also speaks of a relationship that is finished in a way, that’s related to the mourning in the Secret Garden story now that the mother is gone. The Indians have also left their home, torn away from this land.

AG: “Place” and “space” are important themes in Mary Mary. M.’s house is in southeastern Ontario, and she tells the story of her great-great-great-grandfather, who was a settler. She also mentions the First Nations people who were there at the same time. I felt I couldn’t discuss this specific place without talking about the histories attached to it. Again, there were stories behind the stories and I wanted to bring them forward. All the quotes from First Nations sources are directed toward people of European descent, and are about European colonization and oppression of Native American cultures and societies. I didn’t really use any Native myths per se. But it’s interesting that you say that Native people have left their home. Because M. quotes the famous speech of the Duwamish chief Seattle at the signing of the Medicine Creek Treaty in Washington Territory in 1854. Chief Seattle was saying that his people were doomed now that their lands were lost and the reservations were being set up, but he also said that his people would never really leave this land they love, and even when the white man thinks they are all dead and gone they will still be present in all the places they used to travel and inhabit. One of the things he said was: “The dead are not powerless.” It’s an idea of a relationship to a place that’s very different from the one I grew up with. My colonial heritage — the way non-Native North Americans tend to think — tends to treat a “place” as a commodity, a locus for the accumulation or representation of certain kinds of personal or corporate power. I wanted to suggest the value of recognizing a sense of space different from that colonial one. I used the quotations from Native spokespeople to get at these ideas, but the quotes represent a range of opinions rather than a homogeneous viewpoint. That was because I wanted that part of the film to remain unresolved. I wanted an audience to notice the question of land claims, for example, but I didn’t want to put closure on the issue in terms of wrapping it up nicely with a bunch of pat answers. I thought it was better if people who saw my film were left thinking about the issues. The situation of land claims isn’t solved yet in real life, and although I’m pretty clear about where my sympathies lie, I thought it would be false and less valuable to simply make another film that claims to have the answers for Native people — or for anyone else.

MH: How did It Starts with a Whisper (25 minutes 1993) begin?

AG: After Mary Mary I volunteered at the Native Women’s Resource Centre for a while, helping with their newsletter. We were always running short of artwork, so I was frequently on the phone soliciting work from Native women artists. Shelley Niro was a great resource, always ready with small drawings we could use. I asked Maddy Harper, who ran the centre, if I could do an interview with Shelley for the newsletter and she said sure. So I went up to Brantford and Shelley and I really hit it off. Out of the blue she asked if I wanted to collaborate on a film and I said “Yup!” She wanted to make a film that would address 1992 — the 500th anniversary of Columbus reaching the New World. With funding deadlines looming, we fleshed out a story. It would be about a young girl and her aunts who go on a kind of pilgrimage to Niagara Falls on New Year’s Eve. We received a bit of money and started building sets, making costumes and shooting backgrounds, still working on the script. Shelley wanted to screen the film at midnight on the last day of 1992. I think it was about getting the last word in! That gave us just nine months to pull the whole thing together.

MH: Can you describe the film?

AG: It’s about Shanna Sabbath, a seventeen-year-old Mohawk girl torn between traditional Native values and her need to come to terms with contemporary life — as represented by her miserable secretarial job in the city. She has three outrageous aunts who sometimes appear as “matriarchal clowns” or spirit guides. One of the aunts wins a weekend in a honeymoon suite in Niagara Falls. New Year’s Eve is coming, so the aunts decide to take Shanna and make the trip to the Falls. Shanna is depressed, but her aunts are irrepressible. They poke fun at each other and at Shanna. What they are really doing is teaching through humour, trying to get Shanna not to take herself too seriously and to enjoy and appreciate life. When they get to the Falls, Shanna can’t stand it any more and runs off. She encounters Elijah Harper in a dream. He symbolizes spiritual and political power. He tells her not to feel guilty about living her life, helping her put things in perspective. When she returns to her aunts she’s changed; she’s become one of them. Together Shanna and her aunts do a musical number in their hotel room and a little New Year’s Eve ritual in front of the Falls. Then they watch as fireworks explode over the Falls and it’s 1993.

MH: How did you collaborate?

AG: It Starts with a Whisper was co-written, co-directed, co-produced, co-everything. It was a film about Shelley’s experiences more than mine, but I had some film experience and she didn’t at that point. I think we tried to respect each other’s experience and listen to each other as much as we could. We never had any knock-down fights, although there were times when our different cultural backgrounds made it hard to understand each other. On the whole it was a great experience, and I’m happy with how the film turned out.

MH: The film makes a conscious effort to entertain.

AG: I guess the best example of that is the musical number in the hotel room. Shelley and I wrote the lyrics to a song called “I’m Pretty.” It’s a “he done me wrong” song, but it has a really strong political subtext. It starts out: “I’m Pretty, Yeah I’m Pretty, I’m pretty mad at you.” But it was still fun and entertaining. The sequence was a parody of a music video, set in this schmaltzy hotel room, with the aunts in wild evening dresses and outrageous high heels. It was a big collaborative effort that was just a lot of fun, and I think it’s fun for people to watch because of that. Shelley and I both felt that too many political films don’t have a strong political effect. Shelley was particularly concerned that a lot of representations of Native people stress the depressing. But her attitude was that there’s so much to celebrate, and many aspects of Native life have never been shown on film before. We were trying to be political by creating this celebration. I still think that’s pretty important.

MH: What do you think about avant-garde film now?

AG: To me, the whole film-versus-art theme continues to be a mysterious phenomenon. There have been a few times when “experimental” film has overlapped quite substantially with visual art. In the 1920s for instance, and again in the 1970s with structural film. There was a big backlash against structural film that struck me as pretty illustrative of the differences between those two worlds. Structural film was accused of being co-opted by the world of cerebral, minimalist art — the colour-field painting crowd that was surrounded by lofty talk, big bucks, that kind of thing. A similar critique of that milieu was happening in the visual arts, which took the shift of direction in its stride. The Museum of Modern Art didn’t close its doors, for example. Or the Art Gallery of Ontario. They just adjusted their curatorial directions slightly. And eventually all the anti-object art was co-opted (or incorporated), too. In experimental film, however, there was less accommodation, more purist beliefs. And big institutions for both art and film still continue to treat experimental film as a marginal practice. But now we’re in a more postmodern period, if you like, and divisions are breaking down all over the place. When I show my students really old films by Stan Brakhage or Kenneth Anger, they don’t think they’re outrageous at all (although they sometimes have trouble with films by Michael Snow). But many of the visual investigations those filmmakers were doing have been appropriated and even developed in mainstream media — like music videos and commercials. Almost all film now has at least one fuzzy edge that blends with TV or video art and video technology. Even big-budget features use avant-garde techniques, and vice versa. It’s interesting to note the ways in which experimental film has remained oppositional. It’s been taken up by lesbian and gay communities or different racial groups to express identities that have been suppressed. Sometimes films are avantgarde by default — just because their communities are small or marginalized. It doesn’t necessarily mean the films are weird or inaccessible. They’re just designed for specific communities, and I think that’s great. So avant-garde film has kept its avant-gardeness. And of course it still gets accused of being elitist. Then there’s the trend in visual art to show film or other projected-image work in a gallery setting. It seems unfortunate to me that there isn’t more acknowledgement that the absence of that in the past was due to institutional policies, not to a lack of film that could qualify as art.

In answer to your question, I have to confess that I don’t enjoy some of the avant-garde films I see, but I’m also compelled to defend what you call “fringe” film to those who dismiss it because it doesn’t work the way “good” films are supposed to. It also irks me when people say a film is “experimental” — either seriously or as a joke — to mean that it’s lousy. As though “bad” were synonymous with “avant-garde.” The unrelenting marginality makes me uncomfortable. I saw experimental art as heroic when I was younger and avant-gardeness as “leading the way.” Maybe I miss those idealistic fantasies.

Anna Gronau Filmography

Maple Leaf Understory 10 minutes silent 1978

In-Camera Sessions 5 minutes super-8 1979

Wound Close 8 minutes super-8 1982

Aradia 2.5 minutes super-8 1982

Regards 31 minutes 1983

TOTO 2.5 minutes super-8 1984

Mary Mary 60 minutes 1989

It Starts with a Whisper (with Shelley Niro) 25 minutes 1993

Le Cristal se Venge 7 minutes 1996

Time Release Videos (with Robert Priest) 4 minutes 1998

Magic (work in progress) 4 minutes 2001

Originally published in: Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada, ed. Mike Hoolboom, 2nd edition; Coach House Press, 2001.

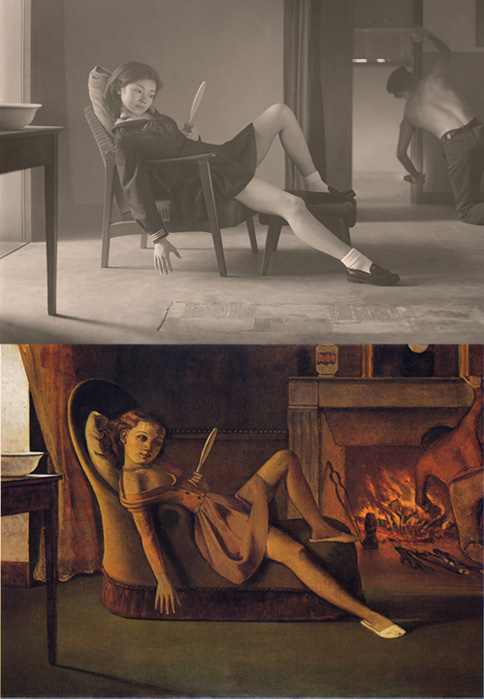

Mary Mary (1989)

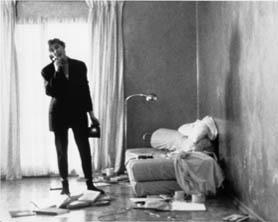

Anna Gronau’s first film in five years, Mary Mary (60 minutes colour 1989), opened March 7 at the Music Gallery in Toronto to a large and enthusiastic reception. It is the story of ‘M,’ a filmmaker-recluse whose withdrawal into art’s dreamed double begins a complex weave of dream diary, recorded conversation, titles and tableau that take as their central conceit the act of self representation. Mary Mary is a psychodrama writ large, a film obsessively self absorbed even as it unfolds the luxuriant vision of a mind at play, replete with swimming polar bears, flash frame Polaroid’s, and two long gowned sisters demurely stepping into the heat of a summer afternoon fifty years before.

The film opens with a long and elegant tracking shot that leads us to the site of M’s retreat, the film’s literal and figurative home. This passage is twice refrained, first closing M’s long drive outside (just one of four scenes set outside the house) and later sounding from a TV set where M sits apparently reviewing the film’s beginning. This reflexive loop joining the film’s dark midsection with its opening threatens to enclose its protagonist in an Escher-like labyrinth of mirrored mirrors.

Canadian filmmakers have lost the naive sense of originary gestures, metaphysics of presence and heroic endeavor that marked the project of the American avant garde of the fifties—a film practice that’s impelled our own. The result? A long day’s journey beneath the twin shadows of the American Hollywood feature and the American underground. Citing through the ruins of modernity and its aesthetics of silence the Canadian avant garde has been delivered into a sense of belated production, afterimages ruled by the word. The consequence has been an insistent examination of the conditions of reproduction. In the hands of the Canadian film artist autobiography becomes a reflection on the possibilities of autobiography, and memory the darkened house where images consume the real. Gronau’s extended prologue takes up this reflexivity in a mirror play of video monitors, lights meters and Arriflexes, chuckling on track as the crew is pictured framing the shots to follow.

Much of Mary Mary moves between its implicit narrative codes and their eventual betrayal. Cutting from a dreamer to a dream sequence we learn that this is not her dream but another’s, the pictured house is not the one described in voice-over, a dialogue between two people carries only M’s voice sounding from both mouths (although both seem to speak in sync). All this points to the failure of narrative to account for our lives, that the way of our expression, our gestures of work and love exceed any simply linear compact bent on resolution.

Four sets of thirteen titles appear, enumerating in succession a polyphony of influences that move from children’s books to native Indian calls for self government. The wellspring for this intertextual weave is The Secret Garden, an English fairy tale about Mary, an orphaned child who uncovers the family’s secret cripple, teaches him to walk and turns the key to the secret garden that was lost when the mother died. This story, in turn, finds its antecedents in tales like Sleeping Beauty which similarly figures a house fallen asleep after the mother’s death, and Beauty and the Beast in which the dead mother appeared formerly as the young and beautiful bride to an ugly hunchback. Finally there are a succession of native Indian myths surrounding the Bear Mother. Tracing The Secret Garden back to its ritual antecedents in which women and beasts married before the beast’s slaughter, Gronau spins a delicate web of allusion that quietly permeate the film. In her first scene M is shown asleep, finally awaking not with a kiss but the ring of a telephone. But is she really awake? The following scene describes the classic encounter of the psychodrama, as M wakes only to speak with her double while great floating polar bears swim alongside.

M:

‘If that there King was to wake’, added Tweedledum, ‘you’d go out—bang!—just like a candle.’

‘I shouldn’t!’, Alice exclaimed indignantly. ‘Besides, if I’m only a sort of thing in his dream, what are you I should like to know?’

M:

‘Ditto’, said Tweedledum.

‘Ditto, Ditto’, cried Tweedledee.

M’s fragmented blend of identities coalesces at last in the figure of Gronau herself (named ‘A’), who waits opposite her dreamed double. Between the joining of ‘A’ and ‘M’ (‘am’ or being) lies the great tank of amniotic fluid that holds a white bear in suspension. The rebirth (or bearing) M conceives for herself after her long sleep is inextricably linked with this archaic remnant, just as her house has been built on lands deserted by the Indians. Gronau suggests that the process of individuation is finally a political one—that we continue to live between the lines of a history that alternately obscures and illuminates—and that these traces of erasure must be resuscitated if our lives are to have any meaning.

Each scene seems contingent here, isolated glimpses of a whole that remains tantalizing and elusive. Gronau’s dangling of the veil issues only fragments: telephone messages from unnamed callers, disjointed dream memories, snapshots, walks without destination and memories whose purpose is never to attach names and places but to energize new relationships. As M recites in voice-over: “Her life had become these moments.”

M’s solitary musings picture a body of parts recast in the light of representation. Early in the film, wrapped in a fold of silken sheets she passes a hand mirror over herself, looking on as if she were another. Later she snaps self portrait Polaroids—as we watch them develop we realize she is privy only to her reflection, her image, or at best, her abilities to manipulate the means of reproduction. That the film’s calling should be already doubled ‘Mary Mary’ underscores Gronau’s project: to depict the development of reproduction in M’s movement from inside to out, from the secret gardens within only she can till, to the wind swept exteriors that demand a native’s redress, from the house of her grandmother to the political struggle outside the looking glass.

Originally published as: “Anna Gronau and the Rites of Reproduction” Experimental Film Coalition Newsletter (April/May/June 1989). Reprinted as “On (experimental) film”, Cinema Canada (July 1989)