This is a transcript of a talk given by Michael Stone (with some extra riffs I laid in) as part of an online Precepts Course at Centre of Gravity in 2011. This course looked at the five yamas (from the first limb of Yoga) and took them up as precepts: ahimsa (not harming), satya (honesty), asteya (not stealing), brahmacharya (wise use of sexual energy), aparigraha (generosity).

The second ethical precept is called Satya. It’s often translated as truthfulness, but I’ve always felt a little uncomfortable with this idea. It gives the sense that there is some final truth, a last and forever word that never stops shining. And it doesn’t take into account the shifting grounds of truth. Truth is not separate from the one who is experiencing it, honesty is not something out there, like a hammer that punishes us, or a rainbow that we need to be chasing. In the practice of satya, we become honesty, it arises out of the real time situations of our loves and livings. So I’ve translated satya as honesty, being honest with what arises in body, speech and mind.

Soft

The deepest value of practice comes through our commitment to honesty. If you look at non-violence or greed, it’s hard to enter those principles unless there’s honesty at the base. There’s three levels of honesty. The first is the literal level. In terms of honesty it means being honest with yourself. And when you bring together the first precept and the second — non-harming with honesty — it means that you don’t need to punish yourself for being honest, or being dishonest. The practice is about being as clear as you can manage, and to open to this transparency with softness and non-harming. What happens when we get tight and judgmental about honesty? I think it encourages us to be less honest. Some of us are rewarded as children for being dishonest, we might be told we should be honest, but the underlying message is: if you’re honest, and tell me about what you’re doing wrong, you’re going to get punished. This is a good way to foster dishonesty. The precepts aren’t another arena for self-harm, but a place where the clarity and softness one brings to oneself is then extended to others.

Atone

In Japanese, the word for repentance or atonement is sangay. I like the English word for atonement because it’s actually at-one-ment. The Japanese term sangay is made up of two words: sang is confession, and gay means regret. I think this is a fabulous way of translating atonement: confession or regret, or confessing what we might regret. When we use these words—confession or regret—I think we can boil it down to learning. This is how we learn. We do something unskillful and then we see it. It gets brought to our attention, and when it’s brought to our attention we have an opportunity to learn. It really reduces our blindness because seeing clearly is the practice of atonement.

The second level of the precept of honesty is the compassionate level which is the underground garage of ethics. Why am I speaking to myself this way? Why am I not looking at this situation honestly? Why do I want to speak to someone in this way? It’s a level of investigation that is not ideological or philosophical. And that takes us to the third principle which is committing to a life of honesty by becoming honesty itself. The koan level means living honestly, living simply, and it’s also a riddle. It’s an invitation to practice the impossible, to enter the impossible, which means living in the interconnectedness of life with a real commitment to being honest with the faces that meet our face.

Non-harm

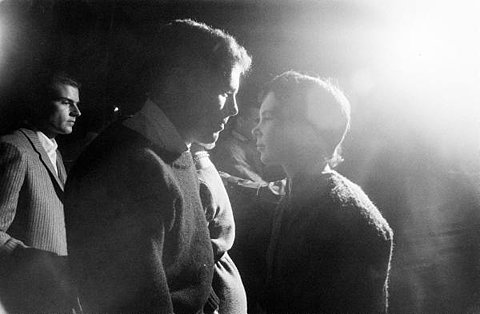

All of the precepts flow out of the first precept of non-harming. If you isolate the practice of honesty, it might mean saying whatever’s on your mind all the time which would be like growing a tongue out of sandpaper. Honesty is tempered by the first principle of non-violence which means that we’re honest while keeping in mind our commitment to kindness, our commitment to not causing harm. This requires some diplomacy. When someone speaks to you dishonestly, or with the intention to cause harm, the precepts can offer a helpful frame so that you can see how their lives have been restricted just like yours, and how they are continuing to act out of old habit patterns. Every moment, even and especially the difficult moments, is an opportunity to wake up, and realize our interdependence. Our fundamental intimacy. We’ve all been hurt by our parents, or by lovers and friends. We’ve been abandoned, people have said things that have been crushing and unkind. But over time, as we offer in place of the reaction shot of outrage or anger, the reaction shot of curiosity, we can start to trace the roots of current misbehaviours back to some difficult formations. A mother that wasn’t a mother. A father that was too much of a father. Using the precepts as a lens, we can come to understand how the angry person in front of us is a person just like we are, and is living inside very similar kinds of restrictions.

Sometimes when you can’t be awake, you just notice that and it paves the way. Otherwise the practice can become so idealistic. Sometimes all we can do is have warm tea and try to survive the party.

Sometimes, the three syllable word I like to use for confusion and uncertainty is: honesty. In wide shot, from the vantage of another planet, or even a tall building, it seems crisply defined. But the closer I get the murkier it appears. Here are a couple of reasons why.

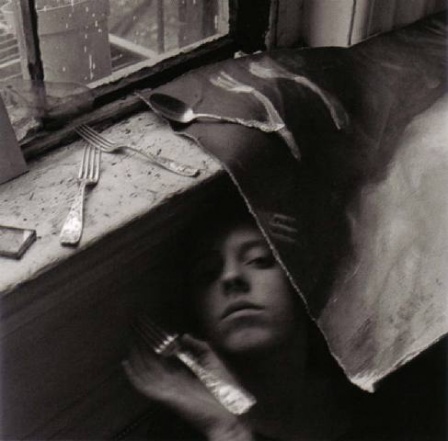

Psychoanalysis offers us the helpful idea of transference. Transference means that I’m not only talking to you, instead, I’m holding onto two or three early childhood action figures and projecting them onto everything around me. When I read a book I’m back taking milk from my mother. My zafu and cushion, of course, are my dad, cheek to cheek once more. Good old dad, steady and reliable and indifferent. Actually in my case, my father is my mother, but that’s another story. What transference means is that I am creating my listener. I’m producing them (I mean you) out of my admittedly limited repertoire of guest stars. In this room, for instance, there are many people whose practices are “better” than mine. No no, don’t hide your faces away, I know that it has made you deeper, kinder, more ready to serve—or at least so I imagine—and as a result, everyone of you looks like my mother. Oh yes, as soon as I walk in here I think, “Mama mia, what are you doing here?” And they say you can never go home again. How is it possible to be honest when I can never quite reach across the infinite space of my private movie theatre and take the faces of my parents away from your face? Remind me, please. Who are you again?

The second thing about honesty in speech is that, try as I might, every time I open my mouth I always say the same thing. And the uncanny thing is that as soon as you hear it, you play it back to me, as if it was something you’re thinking too. This is what a conversation sounds like with my best friend.

I told him, “Listen to me.”

He replied, “Oh, listen to me!”

I wondered aloud, “Listen to me? Listen to me?”

He insisted, “Listen to, listen to, listen to ME.”

Listen to me is the first demand of every speech act—but the demands don’t end there, in fact, I have a long list. So even while it seems I’m trotting out some bonbon about what I did last night or recounting a fave movie scene, what I’m doing at the same time is stuffing my lines with demands. Love me. Aren’t I smart and charming? Love me. Please disappoint me in a reliable way. Love me. Love me even though I just did the one thing you said you could never love if anyone ever worked up the nerve to actually do the thing that is the root, the very place that everything un-loved and unlovable comes from.

So tell me—between the face swapping, the personal movie theatre, the all-season demands that make language possible—where is honesty in any of this? Do you think you can help me with that? Dad?

Bullshit

There’s a book that came out a couple of years ago called On Bullshit by philosopher Harry Frankfurt. “While liars need to know the truth to better conceal it, bullshitters are interested solely in advancing their own agendas, and have no use for the truth.” The book’s premise is that a person who lies has greater sensitivity to the truth than someone who bullshits. Is that another version of Bob Dylan’s “To live outside the law you must be honest?” Frankfurt’s book offers examples of how liars feel in their body that they’re lying. Whereas someone who becomes inflated or deflated in themselves, who goes around bullshitting, becomes numb. I think one of the reasons for taking up the vow of honesty is because we live in a culture that doesn’t value being honest with your body, or speaking honestly. Every day we’re sold versions of what we should be, and what our values should be. Kierkegaard said that soldiers can’t kill when they’re by themselves, they can only kill when they are in groups. I think that sometimes the rhetoric of our culture fools us into believing in versions of ourselves that are not honest. In this sense we can see how what the Buddhists call the three poisons of greed, ill will and delusion, keep us from being honest, keep us in a state of confusion and doing unskillful things. Part of our precepts practice is simply being honest about that. I like to translate unskillfulness as clumsiness. When I can think of myself as a clown doing stupid things, it helps me ease in to where I’m not skillful. Part of our job—especially when we’re in a crowd, or when we have an internal crowd—is to really be in touch with our heart, and what’s true for us.

Refuge

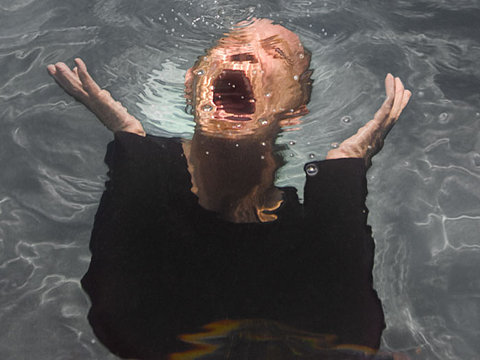

When you take the time to be in that pressure cooker, to look at something honestly, but without the intention to cause harm, then you enter the second precept, which is to live with honesty and non-violence with your whole body. This is what we call taking refuge. In the Pali language, the word refuge is sarana, which means protection or shelter. Refuge is a good translation because in Latin fugere means “to fly back.” Taking refuge means to fly back, to fly home, to return, to find our true home, the place we really belong. And in Zen it’s said that taking refuge in your true or your original home means taking refuge in the Buddha, that’s who we most truly and deeply are. To take refuge in the Buddha is to return to your true home, to return to it over and over, which is the primary commitment to our lives. To live from the place that is your Buddha nature is to live from the place that’s honest.

Talk Practice

Amy meets me in what is left of the Zagreb Deli. We’re not in Zagreb though it’s impossible to tell, entire cities can be packed up and remounted in a single diner, in a look that flashes across a face, in a bangle that hangs off an aching wrist. She’s been busy doing an honesty practice with someone she’s been getting to know her a little too well, she’s been fast tracked into the express lane of intimacy, even though it’s all just talk. And what is talk after all but a series of entrance and exit lines, a way of opening and closing? Here’s how it works. She gets together with her talk partner and one of them holds forth for twenty minutes. No encouraging words or nodding yes from the other side, instead, the whole body listens. And then for the next twenty minutes the listener becomes the speaker. When they’re done both of them can chit chat, but the hope is that no one will offer rhetorical band-aids or home made cures. We’re not here to fix anything, only to listen. To bear witness. And the subject? The subject is honesty of course, how have I been honest in the past few days, and how dishonest? They’re talking about talking, how have they been speaking to themselves internally, about themselves, and how have they been speaking to others? How honest can you be about honesty, anyways? This is what she tells me as we dig ourselves deeper into the Zagreg deli, these are the words that occur to her. And she relates them as if language itself was the scene of an accident. How I wish I could draw for you her widening eyes as she draws the picture of surprise, again and again. I have to remind myself: she’s still young. She still has the luxury of surprise.

“The trouble with honesty is that it is rooted somewhere in between silence and language, in spaces unobstructed by noise, and yet it can only be expressed with words or actions. I really started to notice this curious sub-lingual quality of honesty by reflecting on my weekly meetings with my talking partner. I found myself showing up with the same attitude every time. I would say to Rae Anne, “I really don’t feel like talking this week. You go first. No I mean it! I’ve seriously got nothing to say,” and she would kindly oblige me, sharing her thoughts and feelings with me for twenty minutes, and then it would be my turn and I would reluctantly let a few sentences trickle out, my gaze fixed on the timer in front of me, and before I knew it, twenty minutes had disappeared and I would go into overtime, scrambling to tie up the loose ends of my many thoughts.

It became somewhat of a running joke between us, a knowing smile spreading across Rae Anne’s face the moment I mentioned my lack of anything worthy to talk about. There was something so peculiar about the way my initial words belied the things inside me that were trying to get out. That such a sharp disconnect could exist between what I thought I felt, and what was actually capable of coming out of my mouth when given the time and the space, amazed me each and every time I noticed it happening. This phenomenon made me extremely self-conscious in my relationships with others, but especially in my relationship with myself. Communication itself already invites so much potential for misunderstanding, and now I not only have to worry about someone misinterpreting my words, I have to worry about my words misrepresenting what’s going on inside of me.

So it turns out that the most difficult thing about honesty isn’t necessarily finding ways to express it, but finding honesty itself. I am concerned that honesty is so often shrouded by habitual reactions and patterns of speech. I do think it’s possible to locate honesty, but I often wonder what the point of all this self-inquiry is, when it only seems to dangle an unattainable ideal (that I have vowed to attain) in front of me. Honesty is a dynamic process. It changes over time; over minutes and seconds even, but honesty also means recognizing that there is no one single truth at any given moment. I’m not sure I’ve gotten any closer to finding the honesty within myself, but at least I am starting to know where to look. When searching for honesty, it is especially helpful to respectfully and compassionately tell your many selves to be quiet. After that, you wait and see what comes up in the absence of noise. You wait and you listen, you listen and you wait. And eventually, with any luck, the incessant human need to verbalize will be replaced by a feeling, and when your actions and words spring forth from this feeling that is cultivated by sitting still and creating space, they will be infused with honesty.”

Circle

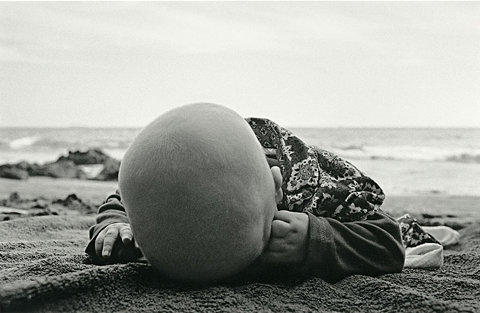

You follow your intentions back to the source and what do you find there? They’re always in motion. At the source of your life the precepts are always in motion. Echoing the circular action of our lives. When I say something to my son that’s unskillful, within a few weeks he says it back to me. I hear it again through his small mouth. To see the circular nature of a river. Or the circular nature of a cloud. The circular nature of the precepts is to see the feedback loop of who we really are. And then we can see how our actions sculpt us. We can see that karma is not something that happens to us, karma is something that we are. We are this circular feedback loop and our actions matter. What honesty teaches us is to be content and satisfied with what we have, and to listen to everybody, even those places inside or outside of us that we have a really hard time listening to.

The precepts teach us how to have wise restraint, not needing always to go out and get something extra. Maybe there’s something I really want to say to somebody, and it’s just not the right time or I don’t think they can hear it. Can you speak in a language that someone else can understand? So often we want to be right. We can mistake being right for being honest. But being honest in a situation means also recognizing that at this moment, the other person might not be able to hear certain words, whether they’re true or not. And right now perhaps there’s certain things you’re unable to hear, unable to bear. Sometimes when we’re feeling small and shattered we need a bit of time to pick ourselves up from the floor before we can face up to the unadorned truth. The practice of honesty means knowing where you’re at. It means knowing how small you are, and how large youare, and how small the other person is. We’re changing all the time. Some mornings I wake up and I’m a four hundred kilo ship anchor. Some mornings I wake up and I’m smaller than a pool stick. And each of these self forms has a language attached. Sometimes your best friend can tell you something that your partner can’t. When your partner says the same words, even if they’re whispering across the room, it sounds like they’re standing up on a chair screaming them out one syllable at a time. The practice of honesty is intimately related to the practice of right speech. And right speech is always situational. The same phrase, the same sentence, can sound so different coming out of different mouths. The precepts aren’t about memorizing a set of principles, they’re a dynamic flow of yoga, arising again and again in the conditions of this moment. Honesty is one of the most difficult of all of the yoga practices, because it happens in real time, and in relationship.

Withhold

Sometimes I’ve felt in past relationships that if I shared certain feelings I had, or certain parts of myself, it would threaten the two of us. Have you ever sang this song? There were parts of myself I couldn’t see fitting into the relationship so I put them all in a box named “Later,” and I shoved it to the back of the shelf. I couldn’t let those parts come alive, I kept them out of my heart and outside the heart of the relationship. When I asked my friend Babz why she was getting married for the fourth time, she said that falling in love means being with someone who gives you space enough to be all of your selves. All of your self presentation models are on view, and they’re all OK. I think what she was saying is that love doesn’t mean saying yes to the highlight reel of someone else’s personality, the smooth party chatter and excellent posture. It means finding the moments in their svarupe, their self form, that are crumpled and broken, and being able to hold that. What I was doing wasn’t honest, finally, because I was holding something back, I wasn’t all there. And this was only the beginning of the retreat. This action of withholding, of refusing to allow certain parts of myself to be laid out (the playful goofy side, the morose depressive side, we have so many people in us!), meant that I was already walking out the door even as I was walking in.

Over the years I’ve come to see that other people pick up on this withdrawal and retreat, and then they aren’t fully given permission to share their whole self, because they don’t see your shadows creeping in. I notice that if I make a vow to give myself permission to uncage the ill-fitting parts, as scary as that can feel sometimes, then it allows the other person to respond “in kind”, as they say, and maybe over time share parts of themselves. Your sharing gives them faith that they can share. And that’s how a relationship can flourish because we’re valuing a self form in all of its idiosyncrasy. Relationships can only flourish in diversity, which means including the whole choir of ourselves, the entire congregation, and particularly the small and unwanted parts of ourselves. Otherwise relationships can grow stale because we are trying to squeeze ourselves inside the smaller, tighter cages of the perfect people we’re supposed to be with each other.

When we are in relationship with other people we can’t help but relate them to images that we have of how things should be. We want them to meet those unconscious images that we have of what a relationship looks like, of mutual duties and responsibilities, of entrance and exit lines. Nobody can ever fit that image, it’s impossible. So over time as a person really shows up and starts to break through the image, as they move towards us, we have to enlarge our view of the other, and that’s when relationship begins to happen. But what tends to occur is that we can get stuck in our previews, we tighten up around our image of them, and they’re doing this with us of course, they’re also working with their image of us, so there’s these two image makers creating images of each other, trying to do whatever they can to hold onto them. And in so doing there’s a co-dependence that happens, we depend on each other’s image making. We like the image that they offer of us, and they like the image we offer. And we’re not fully ourselves. A kind of merger takes place and maybe this is one of the reasons why some couples hide from the social world, maybe at some level they’ve created such definite images of each other, of themselves as a couple, that too much relating outside the apartment threatens the image the two have so carefully constructed.

Lying

“The successful lie creates an unnerving freedom. It shows us that it is possible for no one to know what we are doing. The poor lie—the wish to be found out—reveals our fear about what we can do with words. Lying, in other words, is not so much a way of keeping our options open, but of finding out what they are. Fear of infidelity is fear of language.” (Monogamy by Adam Phillips)

How do we keep words and feelings connected? This is part of the practice of honesty. Over time, as we bring these words and feelings together, we can appreciate our old feelings, and not have to get attached to our fixed stories about them. Have you ever had this happen? You meet someone new and that moment arrives when you both begin to open up, and speak about how you’ve been hurt in the past, or the ways you’ve tried to be open in the past. And all of a sudden the words stick in your mouth, you just can’t trot out those old versions of yourself anymore, they don’t even feel real. And then you start to say the words you don’t know, you start to describe feelings you didn’t even know you had. This moment of invention is a moment of returning home, you’re coming home with your language, you’re connecting words and feelings again, instead of settling back into the retirement home of your old stories. The good reliable stories, the ones that entertain all your dinner party guests, the ones that maintain a righteous mix of sympathy and humour and just enough candor to keep people hooked without the sense that they’re getting any of that emotional dirt on their faces. These old stories perform a self, they are part of the necessary armour of the self, and when you’ve been shattered you need these stories to take refuge in, but somewhere down the line, you also need to let them go, to let them get old and pass away.

Fresh

So much of the time we’re not really meeting the moments in our lives a fresh way. We’re applying to moments that come at us an ideology or philosophy or quick emotional reaction and we’re not allowing the moment to touch our hearts in a deep way. How to respond from the heart? To say, “I don’t know.” To be able to hold back the tendency to blame in or blame out. And to have as the underlying intention of wise speech the commitment not to do harm.

When I was working as a psychotherapist I had a client whose sister was raped by his step father. The family had a lot of strong feeling about it, there were three therapists, and we all worked together with the three siblings. The trauma in this family was really intense, and five years into our work it turned out the story wasn’t true. The daughter had made it up, and was doing this to break her family apart. Suddenly all the feelings that had felt so honest were exposed as a fabrication. This possibility had never occurred to me, it had all seemed so real. We were exploring everyone’s real feelings that came up—only to learn five years later that it wasn’t true. That was an incredible learning experience for everybody. Just because you feel something, and it’s true for you, it doesn’t necessarily mean that that’s what reality is. That’s why relationships are so difficult. We all prefer to imagine: oh, I feel this way, therefore it must be true for all of us.

Honest

Imagine if the only precept you worked on for the next five years was being honest in how you speak to yourself about yourself, in working through the tendency towards exaggeration or self judgment. That would be a profound thing for your own life and the lives around you. And the third thing is being honest with your mind, being able to look honestly at your own mind, and to look clearly at the minds of others. This is another really deep practice. I really encourage you to take up honesty as a practice and to see how it is an expression of non-violence. I’ve focused mostly on non-violence of speech because I think that’s where most of us get caught. Whether it’s via selective hearing, or saying what we think others want to hear, or whether it’s not really speaking honestly to ourselves about what’s going on in our own hearts. The core of honesty has to do with speech. Ethics is something one becomes at a cellular level rather than just an idea that we’re trying to reach.

Letter

(after Jan. 22, 2011, an all day sit at Centre of Gravity)

Dear Michael,

I watched my partner’s spine as I breathed. I watched him. Breathing. All day. I watched him breathe in front of me. I watched and I breathed and I was totally, totally silent. Then at the end of the day, as I was leaving, I said goodnight and he said goodnight and then I realized I saw the whole thing. I cried. I saw the whole thing, the whole him, the whole of the both of us. Our lives. What else is there?

And then I realized I knew him better than I know my husband.

X