Steve

(Introduction to Steve Sanguedolce’s Blinding at Innis College, Toronto. January 21, 2012)

When you’ve only experienced someone in close-up, how can you talk about them in a wide shot? What does the private language of friendship sound like in a crowd? Too late, too little or too much? Eulogy or show business?

I didn’t meet Steve Sanguedolce at Sheridan College, though we both cast a shadow across those hallways, he was a year or two ahead of my cohort that included a schoolyard boy no one got along with – except for Steve of course – and it was through this unwanted misfit that we met. I think Steve has a feeling for the ones that don’t belong, the awkward outsider, as if he were the one (and not his parents) who had made the trek from the sheep grazing farmlands of Sicily so that he could raise cute loveable animals in an Eglinton Avenue apartment that would be slaughtered one after another. What’s for dinner ma? Mario the pig’s for dinner, and nobody leaves the table until it’s all down the hatch.

I met him shortly after his kind of, sort of, almost, conversion experience. He was always hopped up on the tech side of things, he had the kind of hands that could pick up a dirt-filled, left behind machine and bring it back to life. Let me mess with that. But after a pair of slick, nearly commercial shorts in a program that used to emphasize what Apple would have branded I-cinema, he made a dramatic turn, and started using his camera the way an artist might lift a pencil to find the way shadow falls across a face. But there was a cost to crossing over, of leaving the old and nearly innocent dreams behind. They don’t tell you about the cost, the terrible toll it takes, sometimes, in becoming an artist. It can be a wound that never heals, like a bird that comes to visit you every day to eat your liver, and slowly, and this is the other thing they don’t tell you, slowly you learn to look it in the eye and say thank you.

The wound, the conversion, the opening. Perhaps it’s true what they say, that the wound is the path.

In 1983 he made a feature length almost collaboration about mental illness, shot in a brooding high contrast black and white that punctuated psychiatric survivor interviews with extended lyric interludes. He had started making documentaries, because the people around him, the stories around us, were stranger and more beautiful than anything fiction could ever conjure. Here’s the crude sketch, a life’s work as sound bite: there were three experimentalist home movies made in the 1980s and early 90s, followed by another three films made in the last decade that each started by reworking the Catholic confessional as a place of testimony. In place of a priest, a microphone. Take, eat, this is my movie.

To go back and colour in some of the lines. In 1985 he returned to his roots to make Woodbridge where his expressionist camera stylings took aim at the containers of church and family. We made a film called Mexico together and then I moved into his apartment where we were more or less living together anyways because it took so long to cut. Rhythms of the Heart (1990) was made while taking his camera out for a walk, now to Niagara Falls, or towards a lonely sax player, or a couple making food. He found his centre late in its making, in a brief flare of a romance that was recast for the camera. In the cinema, you only live, you only love, twice. Sweetblood (1993) reworks the idea of the family photo album, it’s made almost entirely out of still photographs and printed poetic overtitles. Away was his first venture into fiction, set in the off-stage rooms of Apocalypse Now. Smack and Dead Time, his two long films from the past decade, are hand coloured docs fuelled by interviews with people suffering from addiction.

Unlike the digital bingers of today, the ones cramming for deadlines, or chugging out six or seven little digital droppings at a time, Steve works on his movies day after day. It’s an art that takes time, hard to imagine now, when we seem to have run out of time.

He is someone dedicated, in his language, in his speaking practice, to a restless flow and excited circulation, forever pushing the word accelerator until the censor overloads and the sentences arrive as surprise and invention. The movies are by contrast a slow motion slog. They are slowness, a necessary time machine perhaps, a place before and after language, a frame where hundreds of hours are spent in contemplation and material reworking. How long does it take to look at what can’t be looked at, to tell the story that can’t be told?

My friend Tomas saw the movie we’re going to see tonight in Jihlava, the east European capital of documentary movies. He wrote me, “Such a fragile inside view into the deep, hot heart of a life and nobody is interested? I still have some visuals from his film in my head, probably forever. And these personal stories, the sound and colours and everything together creates a great semantic gesture, as the structuralists say. And the author himself, so strange that completely extrovert person can create so introverted and imaginative movie. Yes, I would never thought he can make this film, but it makes it more interesting.”

But why don’t we let him speak for himself? Friend, collaborator, teacher, student, father, artist, banjo player, hockey goalie, sweet blooded porkpie hat machine, talking book Steve Sanguedolce.

To go back and colour in some of the lines. In 1985 he went back to his roots for Woodbridge where his expressionist camera stylings took aim at the containers of church and family. We made a film called Mexico together and then I moved into his apartment where we were more or less living together anyways because it took so long to cut. Rhythms of the Heart (43 minutes 1990) looked at failed romance through the lenses of landscapes, cooking and music. Sweetblood (1993) reworks the idea of the family photo album, it’s made almost entirely out of still photographs and printed poetic overtitles. Away was his first venture into fiction, set in the off-stage rooms of Apocalypse Now.

Sex, Madness and the Church: an Interview with Steve Sanguedolce (1996)

My friend and fringe comrade, Steve is the one who knows how to fix everything, at home with things in the world. He rewires his house, drives us to Mexico, talks me through the new emulsion numbers, and all the while we are talking about love. We talked every day on the phone until we wore down the number pads, made a movie together and how many nights, and how many more to come.

SS: My old man was always saying, “You can be young without money, but you can’t be old without it” and it seems like my brother Sam and I spent most of our time together trying to work out our big score. Sometime around when we were six or seven, Sam got it into his head that if we could grow a third arm we’d be right for life, and for weeks we’d argue about where to put it. Sam figured it should come straight out of his chest for the surprise knock-out punch, while I thought it should run out of my butt because I figured that furniture would just die out as we got older and that I’d want something to sit on. We made a little lotion out of eggs and arm hair and a little blood and every day we’d rub it into the spot where we wanted our new limb to grow. We never did grow that extra arm — but Sam did have three nipples, just like Goldfinger in James Bond. I guess it’s not that unusual. But Sam always said that was the beginning of a double that he was growing from the chest out. He always kept a bandage over it so no one would know. He’d decided that one day his double would appear in the world to take his place and he could get on with his real business, or maybe, he’d wink at me, maybe he was already gone.

I got a movie camera when I was thirteen for my first communion. The first connection with God and film. My uncle told me, “Start shooting right away. But never move the camera too quickly.” In Grade 12 we had a screen education course and I made some films. The next year I made films instead of essays in English class. I was good in math — everyone said I should be an accountant — but I didn’t want to do that, so I headed to Sheridan College to learn more about filmmaking. 1978 was my first year there and I left in 1981, at the age of twenty-one. I made two 16mm films that were slick, fast, and commercial. They’re consistent with what I’d do later, trying to get the camera to become performative, though it was done in a more rigid way. I did some commercial work, then I got a Creative Artists in the Schools Grant to teach super-8 filmmaking at my old high school. I found Carl Brown there. We had gone to high school together and met up again at College. He said, “I’m going to make a feature-length film on mental illness, would you be interested in working on it?” I was skeptical but said okay. We spent a year together working, fighting, and basically living together.

We based Full Moon Darkness (with Carl Brown, 90 minutes black and white, 1984) on Thomas Szasz’s book The Myth of Mental Illness. Szasz speaks of mental illness as a metaphor and the need to separate psychiatry from the state. He relates the forced incarcerations and mandatory doping to an extension of the church’s power — today psychiatrists determine who’s “crazy,” who should be shocked, etc. We talked to people in the mental health establishment who agreed with Szasz but wouldn’t appear on film or write us letters of support. We ended up with a group called On Our Own, a self help group of ex-psychiatric inmates (as they refer to themselves). They publish a newsletter called Phoenix Rising which Carl edited for eight months. In order to make the film, we felt we needed to come to terms with what these people were doing, how they were living, how they felt; we didn’t want to roll in like an NFB documentary, ask a lot of fast questions and leave. So we hung around, met a lot of the inmates and got to know them pretty well. We were close. We decided that we wanted to interview some of them. These interviews would be relieved by “demonstrations,” showing via subjective camera work my interpretation of what they were feeling. These rolls showed the living conditions in Parkdale, the landscape of their surroundings, but also their inner landscape.

An Italian scientist named Ugo Cerletti invented the whole notion of shock treatment by applying cattle prods to pig’s heads, making them more docile for slaughter. This set the stage for shock treatment. I snuck into the slaughterhouse with a camera taped under the sleeve of my lab coat; we ended up with a whole roll of images that dealt in some way with mental illness — the incarceration, the entrapment, living in these close quarters. A year and a half later, in early 1983, we got $8,500 from Canada Council. Then we started the interviews. Thomas Szasz was the first. Don Weitz, an ex-psychologist and ex-inmate, was very keen to speak. He was very powerful and outspoken. Then there were three ex-inmates, two women, and a man. The last interviewee was a priest because the history of mental illness begins with the church. Foucault talked about it some, claiming that at the moment lepers disappeared from Europe, the insane began to show, and that this kind of outcast had its origins in the church.

Szasz was the first person presenting the film’s argument about the history and the pitfalls of psychiatry. He was shot in a very straight documentary way by Phil Hoffman with virtually no camera movement. Then I shot Don Weitz and the camera started to become part of the dialogue. As he became more and more enraged with the crimes against humanity (as he called them) the camera would jump closer and closer to him, following the intensity of his speech and the patterns of his room. Then we filmed John Bedford who was one of the inmates — he’s very soft spoken — and as he spoke he became more and more faint. When I took the magazine off the camera it accidentally flew open and I shut it in a hurry and thought, shit, we’ve lost it all. We got it back and he starts off properly exposed and as his voice gets fainter the image becomes more and more fogged and as he finishes the film totally whites out. It was amazing for all that to come together. Once we finished filming it took us a week to edit.

MH: Did you cut it together?

SS: We had battles. Carl often had the final word since he had the clearest idea of where the film was headed. This was the first time I’d edited anything over four minutes long. Carl was very dictatorial in the way he worked. Unless I was strong in what I wanted there wasn’t much allowance for change. It took me three years to cut Woodbridge and Rhythms; why should Full Moon take a week? There were real problems with Carl and I over the ownership of the film. All of a sudden, I was only getting tech credits and Carl would get “a film by.” We haven’t spoken to each other since.

MH: How did Woodbridge (32 min 1985) begin?

SS: The first time I met Ermanno Bulfone, the priest we shot in Full Moon, we were playing ball hockey in the school gym. He came by and stuck this hockey stick in my chest and said, “Who are you?” I asked him back. He was the school priest and everyone was supposed to be nice to him I guess, but… He invited me to his place to talk about a film on Woodbridge. I wanted to talk about the first line in Nietzsche’s Zarathustra which read, “God is dead.” He didn’t like that but he was fascinated with me, and felt someone should make a film about Woodbridge. Woodbridge is a small town just north-west of Toronto that has 70,000 inhabitants, eighty per cent of them Italian. It’s become a place where middle class Italians can keep the dream alive.

MH: Why did you leave Woodbridge?

SS: It’s funny, you know. You live in a place for ten years and all of a sudden you realize that the city you’re in is not the centre of the universe. So one day you leave. Just because you can. I remember when my cousin Marco came back to Sicily in a dazzling suit telling tales of Canada. It wasn’t until later that week that he revealed his secret to us — when he opened his mouth, his teeth were uniformly gold. He invited the family to feel them, to assure us all that Canada was indeed the land of opportunity. My father said that Marco owed his optimism to his profession. Marco was an undertaker. His prosperity impressed upon the family two things — that Canadians were consumed with the task of burying their dead, and that in Canada, each of the bodies they passed on the street was filled with gold. We imagined the very rich had gold livers and spleens, each one a walking treasury, and rubbed our hands in anticipation of the day when we too would carry their wealth in their body.

MH: When you made the film you were coming back to a place you once lived. How would it have been different if you’d made it inside the community?

SS: It would have been a bitter film. When I started the film I was still living there; a year later I moved out. I felt the community was stifling, the machismo, the sexism, the closed circle of belief, family problems. There were no choices in Woodbridge, only ways out. I began shooting around the house, feeling all those pressures had come back here as architecture. The film was about trying to reconcile myself with my past. I shot children playing hockey, a community picnic, eating potato chips in church during communion. After shooting Full Moon Darkness, my camera became much more involved and subjective. I could shoot something that everybody sees a million times and make it my own. So the Woodbridge activities — the picnics, the church, the baking, events in my house — were one thread, the personal, subjective stuff another, and the alleyways a continuing motif. I’d go into alleys at night, shine highbeams from my car, and shoot these really dark images pushed two stops so that the grain would start to elicit all sorts of images. I think the film ends quite optimistically now. I come home and there’s a portrait sequence where my family pose before the camera; I showed it to them later and recorded them talking over it. At the end of the film they ask to take my portrait and all they get is an overexposed frame of my face, which is a movie image of the flash going off. I look almost ghostly. For me it suggests trying to give myself but not being quite willing or ready yet.

During our big fight over Full Moon Darkness, Carl would say, “You’re not a filmmaker, you’ll never be one, you’re just a technician,” and I wasn’t sure. I was 22 when I started Woodbridge and I began it with a lot of pressure because what had I done? I’d made some work at Sheridan but nothing in my own way except Full Moon Darkness and that was with Carl, not by myself. Woodbridge took me a long time and I felt a lot of pressure doing it, so after I finished it, I went away.

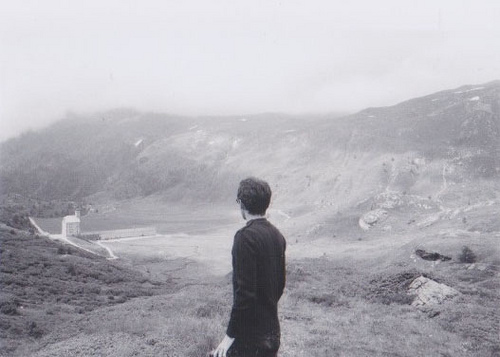

I wanted to leave the whole film thing behind. Going away allowed me to say fuck this, and when I got back I just wanted to shot without knowing how it would fit into a project. I started with Niagara Falls. I tried to get into the mist and the colour and the constantly rising haze while a woman is asking behind me, “Excuse me, are you finished, can I get in now?” The best thing about my landscape work was losing expectations, realizing that what I wanted and what I got didn’t have to be the same. I shot a couple of thousand feet in the summer of 1987, an hour north of Lake Superior. I’d drive along, watch the landscape, get out and start caressing it with the camera. I filmed a waterfall and clouds, walking over rock and forest fires, not knowing how or where it would be used. I couldn’t find anything I wanted to shoot in Toronto. The images aren’t literal, they’re quite abstracted, but they speak of what’s inside. If I take your portrait, it’s probably as much a portrait of me as it is of you. It’s an interpretation. I could make an abstract representation of your face that no one could recognize a human form in. I think that’s what the landscape work is doing, it’s taking the outside and moving it through the veins. It’s not important to name the falls or forest fire, they’re important for their emotive power, for what they might represent.

At the end of 1987 I got my first grant, for what became Rhythms of the Heart (43 minutes 1990). I showed them the landscape footage. I got $7,500 from Ontario Arts Council and $10,500 from Canada Council. While I was struggling with the film, I was going through a relationship breakup. Breakups always take so long — this took four or five months — and we started filming together, not with any intent. First we shot ourselves working together, then we started shooting everything — drinking, fucking, sleeping, crying, laughing — everything that lovers do. I started cutting this stuff into the film but it became very one-sided because I was so careful about how I was pictured. So I didn’t use it. After that, I started seeing Alex. She was already in the film because I’d filmed her dancing on the rooftop. Two months into the relationship we started filming together. We both held the camera, both equally vulnerable.

MH: How did she feel about the camera?

SS: At times it was very erotic, being in bed and fucking with the camera was like being voyeur and participant at the same time. I won’t speak for Alex, but it was definitely not a deterrent to our sex. Then it became really complicated, because we started breaking up. She was sleeping with some other guy and I was heartbroken.

MH: Did the filming have anything to do with it?

SS: No, it was all so fast, so intense, we were getting along so well, but it was too much at once. We were both scared. Then I phoned her and said, “Look, I know we’re not seeing each other and you’re with this other guy and that’s cool, but I’m trying to finish this film. I don’t have enough images, would you be interested in filming some more? I can pay you some money, it would be strictly work.” Was the camera a way to re-enact what we had, or to continue in a way that we couldn’t anymore? I guess it was a way of being with her. This was two days after we broke up. It got complicated. She was very skeptical. She wasn’t sure she could trust me, she was worried about me changing the film out of anger or bitterness because I was so hurt. I asked her later if she thought that happened. She said no. But at the time it was really awkward. But she agreed. She came back for two nights, and we shot everything. The dancing, simulated sex, it was all well executed, smooth, comfortable, and it worked.

MH: How did she feel about being part of this film that you’d already started?

SS: I think that was sort of attractive. In some strange way, film has a sordid kind of glamour, and personal film especially. She’d seen the original footage of my first lover and liked it. She wanted to help. It’s strange to bring a camera into a relationship. It gives it a fixed perspective that experience doesn’t have. What I think I’ve done is to express a pattern I’ve developed in relationships. I get close, uncover a mutual vulnerability, then I get frightened, and emotionally withdraw, finally forcing the other person to leave. It happens time and time again.

MH: As you talk in the film about a relationship that’s finished, we see images of the two of you together in happier times. It’s as if we’re asked to look into these gestures of everyday life, and wonder which already bears the sign of separation. It’s a reminder of how ambiguous the image is and how direct the word is by contrast.

SS: It’s how we’ve learned to speak, not like music or poetry, but like accounting.

MH: The film reframes your diary images, your personal experience, according to its own needs. When you say that the film grants you a clarity or clairvoyance, how is that possible?

SS: It’s all a lie, it doesn’t have anything to do with what’s happened. I reinvent the story while trying to be fair to the people involved. The problem is that images take the place of memory, the super-8 films of my childhood are what’s left in the mind when I look back. That’s when the image stops standing in for something else. It’s all there is. I have an obsession with order and for me making work is an attempt to create order out of the mess that’s around me. In my twenties I was an idealist, I thought my work was going to change the way people saw themselves and the world. And after every film I had a major post-partum depression thinking, “Omigod nobody cares about this.” Making film is just so insular. You spend all that time in the dark, working out the relations between pictures. Getting smaller. Narrowing focus. Wondering if someone else will understand.

MH: I guess we should talk about Mexico (35 minutes 1992).

SS: Mexico was something we made together. It’s one of those films where you point the camera at your head and you end up making a film about your ass. It was supposed to be a film about love. After we’d given up on that, it became a rock ‘n’ roll comedy, a two-screen abstract short, a family/buddy narrative, a mock ad for the tourist bureau. We finally found ourselves home, feeling that this film about was Toronto after all, about the need to die. It’s set up like a series of postcards which carries the traveller through Mexico. Only we realize, as an audience, that the narrator, the traveller, is not able to see anything but where he’s come from. There are several scenes where he’s describing Mexico, only we’re watching Toronto. The whole film narrates this slippage. For instance, the narrative watches guys welding dinosaur bones, putting together skeletons that stand in the museums. He imagines that these are not archeologists at all, reconstructing some past time, but artists, just stitching bones together. He says, “You walk from one monster to the next, admiring the craft and skill these Frankensteins possess. You think: this is how the present understands the past — as a terrible and devouring monster, looming hideously over the population of the present, casting its lengthening shadow over the conscience of the everyday. What they are making then is not an image of the past as it used to be, but an image of the past as it is, not a faithful rendering of times long forgotten, but an image of memory itself.” This insistent conversion of Mexico into Toronto is like that old saying, “I know what I like means I like what I know.” Because there’s no way to escape where you’re from, home is something you pack into the suitcase along with the underwear and the shaver.

MH: Home is also the subject of your next film, Sweetblood (13 minutes 1993).

SS: Sweetblood begins with my name, the name of the father. “Sanguedolce” in English means “sweet blood,” so it seemed an appropriate way to title a diary film. In the film I look at a photo of myself and say, “The picture is me, the lines on my face are my father’s.” It began with my collection of still photos. It’s part of growing up Italian — you don’t throw anything out — so I had all these pictures. I started pasting them up onto boards. One filled with old family portraits, another showed friends and lovers, another showed pictures of adolescence — Bob Dylan at the Gardens and vials of hash oil and Pabsy painting the Scrooge’s face while he’s passed out. They were snapshots, a life’s journey in pictures, an archival committee I wanted to reconvene. I filmed them off the boards with a close-up lens, squeezing out frames like an action painter, adding motion to these still shots, reassembling the family in-camera. I figured the film would be a comedy, a parody of the personal films that I and others had made. I spent a few months writing a voice-over that was supposed to be comical, witty, and insightful. It wasn’t. So I left the film for a few months. When I came back, the visuals still looked good, I just had to toss the sound and start over. The pictures replayed an archive of photographs, and I decided to take the same approach with the sound, so I began compiling sounds collected over the past twenty years — interviews and late night jams, telephone calls and drunken talks, and cut them together as a fragmented mosaic. So now I had photos and voices. But something was still missing.

At the time I was sleeping with a Walkman next to my bed in order to record my dreams, keeping a dream diary. I wrote them all down and then pulled out moments or images that related to the pictures. These became a kind of dream poem that appears in the film one line at a time, overtop the pictures. So you watch the photos through these dreams, the dreams of the past and present joined in the film.

I start crying because I have no shoes

Until I see a man crying because he has no feet

At night

I see a flowered meadow

In it a black coffin

I’m afraid my father is in it

I open the lid

Luckily it’s not him

But me

(text from Sweetblood by Steve Sanguedolce)

Ironically, the film isn’t comical at all. Since all the photos were taken from my past, the film turned towards my relation with my father. When I looked back that seemed the most important thing. That turn towards the father made this light, comical film something very different. After Rhythms I realized that diary filmmaking, with myself as the subject, was a difficult way to make work. It leaves you exposed in ways you can’t predict. I now feel a lot more comfortable showing Sweetblood. It’s still personal, but I’m not in the raw. There are many layers, and the viewer has to work through them, negotiating it in their own way.

MH: Tell me about Away (60 min. 1996).

SS: On our way for pictures and prints at 51 Division, Sam started dumping these hot sapphire rings out the back of the paddy wagon, ankle-cuffed together with me and two greasy wops. He said, “One of us is going to get out tonight and it ain’t gonna be me.” I promised him the next time I saw him outside, we’d spend the rest of our lives together. It looked pretty bad at first, they pulled everything out on him: the time he went across the border in a hot van, the bank job he pulled with a baseball bat and a note that the tellers couldn’t read. But they let him off on a technicality and he skipped town because one of the paisons had paid off the judge. That’s how Away started. It’s about finding my brother. I got word he was stumbling through Thailand, so I went down and shot thirty rolls of super-8 footage, made some street recordings, and caught up with rumours of Sam. Three fellow travellers busted for exotic tobaccos. I shot the cock fights, a cremation ceremony, kick boxing, music performances, shadow plays, live sex shows, and opium dens. I blew it all up to 16mm and the National Film Board agreed to process and print everything. That’s when I received the first money for the film, a LIFT co-production grant of $8,000. I tried to cut together what I had, but what was it? A travelogue? A diary movie? I spent two years cutting it into small bits and putting it all back together again. Every time I just hit the wall, until we talked one night, you remember that?

MH: Yeah.

SS: You had the bright idea to lose it as a documentary. Now it was going to be a fiction film, set on the shoot of Apocalypse Now. I’m hired as an art director, along with my errant twin brother, Sam, who I go looking for on days off. That’s where all the original super-8 stuff came in. Casting seems impossible, until I watch Earl Pastko playing the Devil in Bruce McDonald’s Highway 61 and realize he’s perfect to play me. In Away, Earl meets up with Scriber, an old childhood friend, played by Vancouver diva Babz Chula. We start rehearsals and Earl blows my narcotics budget and almost breaks my back hugging me. But it’s okay, we’re starting to feel more like family. The Canada Council kicks in with $20,000 and we’re set to shoot. It takes three days with a five-person crew and two actors. I hear that Sam’s in Laos and is planning to return home. Another year of cutting follows and the damned thing’s ready. The Ontario Arts Council comes back with another $20,000 to finish it and Sam finds his way home. Somehow he manages to make it back for Christmas this year just in time to see the film up on the screen, and he laughs so hard and parties so late we nearly have to book him into the hospital with alcohol poisoning. So that’s Away, six short years, released beneath the moniker, “Where there’s a will, there’s a relative.” I just hope the next one won’t take so long and that Sam can stay close. Can I go now? My bookie’s on the other line.

Originally published in: Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada by Mike Hoolboom, Coach House, 2001.

The Psychotechnology of Everyday Life: the early films of Steve Sanguedolce

The relationship between bodies and desire is among the oldest subjects in the cinema, underpinning its movement from music hall curiosity to globalized comic books. With the invention of 16mm film stock, cinema took another kind of turn. Though primarily intended for military use, it allowed an avant-garde of a different sort to flourish, as well as a burgeoning interest in “home movies.” Decades of these home-made movies have passed, providing in their orbit a secret and alternative history of the movies. These domestic retreats have also found their way into the hands of artists who have shed new light on identity, memory, and naming. The homing instinct of the fringe has never been more acute than today when a new generation has emerged to shape a transgressively personal work, exposing a hitherto private experience to the unblinking stare of its shrinking public. This emphasis on personal expression has marked the project of filmmaker Steve Sanguedolce, whose work continues to forge new links between movies and home.

Sanguedolce learned his craft in Oakville’s Sheridan College, primal scene of the Escarpment School, and immediately showed a propensity for short commercial work, producing films on boxing and an anti-drinking/driving commercial. Two years after college, his collision with fellow Escarpment Schooler Carl Brown proved instrumental in developing new eyes for motion pictures. For two years they laboured on Full Moon Darkness (90 minutes b/w 1984), a gothic, feature-length documentary that examined mental illness. Episodically photographed, Full Moon‘s blend of interviews and expressionistic interludes focused on Toronto’s self-help group “On Our Own,” a collective of ex-psychiatric patients. It was while making this film that Sanguedolce developed his signature performative camera style, moving in a dance with his subjects, whether a snow fence or a woman sitting on a park bench.

After finishing Full Moon Darkness, he began work on the autobiographical Woodbridge (32 minutes 1985). Named after the Toronto suburb where his family lives, he returns home with a camera learned in the diction of abstract expressionism. Church picnics, lawn bowling, and street hockey games are all refocused under the filmmaker’s unsettling gaze to produce a sensual derangement. Underscoring many of the neighbourhood’s activities is the mythology of Roman Catholicism, pervasive in this predominantly Italian immigrant population. The litany of the church service is continued with the recitation of Hail Mary’s as the filmmaker’s mother rolls bread in a daily ritual. Her living room furniture is wrapped in a preserving plastic for tomorrow’s guests. The slow motion gestures of lawn bowlers are caught in some eternal cycle of body and spirit, every move tuned to a divine understanding.

Woodbridge is an immigrant’s coming-of-age film. The dominant Catholic iconography is contrasted with the filmmaker’s quest for release, identity and escape. It is striking to witness how often this paradigm is repeated in the Canadian fringe, its members subject to a displacement which is everywhere felt but never seen. As their parents arrive in “the new world,” these filmmakers are born and raised in a Canadian setting which overlaps uneasily with past understandings. Haunted by images of a place they have never seen, they internalize the displacement of their immigrant parentage, never quite feeling “at home” in Canada, but knowing little of the geography which continues to sound through their parents. As a result, the present appears in a double vision, overlaid with a borrowed understanding, its constituents standing in a place between old world and new. This place “between” means that things are not what they seem to be. Even as they are drawn to make images in a documentary register, these filmmakers’ expectations are upset by the understanding that something is missing. This distance between an object and its representation has impelled much of the efforts of the Canadian fringe.

In Rhythms of the Heart (43 minutes 1990), Sanguedolce’s affinity for expressionistic documentaries turned to the depiction of a ruined marriage. Part documentary, part fiction, this home movie musical is staged in eight movements with prelude and coda. Begun with the pastel mists of Niagara Falls, the film slowly admits colour and turns from abstraction to representation. Framing this Edenic enclosure are twin texts, recorded vérité style, by an aggressive male opera director whose first word is also the film’s beginning: “No!” In the year-long process of gathering images and sounds for what the filmmaker imagined at first to be a film about music, he recorded dress rehearsals for Puccini’s La Bohéme, directed by Guisseppe Machina. Scrapping the image, Sanguedolce kept only Machina’s voice, using it in ironic counterpoint to images of a more personal order. Part carnival barker, ham actor, and outraged artist, Machina continually decries the timing of his cast and crew, the look of their costumes, the delivery of dialogue, their emotions in performance. Displaced from its original context, these comments are re-directed towards the actions in Rhythms, often casting Machina’s authorial tones over the diary images of the film’s couple: Mary and Stephen. Their diary work and private life appear subject to an unseen control, a voice that amends and makes available to us their most intimate exchanges.

After Sanguedolce’s refigured image of the fall, Machina sounds again, shaming the proceedings and demanding that everything begin from the beginning. The filmmaker now returns to nature, replacing the waterfall’s mist with a billowing white smoke, evidence of a ruined forest below. Choosing to show only the effects of the fire, he shows how the sublime has its origin in disaster. Beauty is once again only the beginning of terror.

After another disgusted intercession from Guisseppe Machina, Sanguedolce offers the film’s third beginning. Racing over rock, his camera pitching earthwards and skywards, Sanguedolce returns to the earth’s surface as if to another planet, wandering without bearings or direction. Spliced into his footfalls are glimpses of a couple at home. As the walk terminates in a rush of sun flares and reflecting pools, these intimations of domestic life expand in a frenzied super-8 collage depicting pre-post marriage nuptials. From their marriage, honeymoon doubts, and institutionalized intimacies to Mary’s last pained leaving scene, Rhythms takes up the trajectory of a marriage’s dissolution. This blend of fact and fiction is photographed largely in super-8, utilizing its lightweight portability, automatic metering, and low light capabilities. Invariably held in hand at close quarters, the super-8 camera is used to squeeze off short bursts of picture, rhythmic phrases that keep the married couple of the film in a continual state of readjustment and realignment. The couple both wield the camera, offering glimpses of sleeping, crying, fucking, dancing, and talking.

If Rhythms‘s opening and closing scenes are set in the natural world, the rest is lensed in a gaggle of enclosures: sparsely lit studio settings, counter tops, or framed bathrooms. This claustrophobic intimacy is matched with a kinetic intensity and gestural camera style whose freewheeling expressions push against the confines of these interiors. While Rhythms begins with an image of the “fall” or fallen nature, it closes with a rooftop dance lit by the city lights beyond. This progression, from country to city, from a solitary watch to a reconciliation with another, provides the film’s essential trajectory. But this passage is hardly straight forward; rather, it consists of a continual series of transgressions (of space, of confinement, of each other) which are remade and redressed in succeeding parts of the film. Drawn through a succession of enclosures, this couple makes their final escape from each other, their words an unanswered monologue of separation. Taking up the means of representation for themselves, they are finally able to come together only as an image, an image whose mediated distance reinforces their own sense of estrangement from one another.

Mexico (35 minutes 1992) is a collaborative effort made with this writer, an episodic road movie which unfolds like a series of postcards. As the unseen traveler ventures through war museums, dinosaur ruins, jungle factories, the judo champions of Monterrey, and an explosive amateur bullfight in Mexico City, we hear a wry voice-over which insistently converts his place of escape into his past. “You drive through the suburbs of Vera Cruz. You pass the telephone exchange, the waterworks, and the white picket fences that surround the houses in the district, but there are no people anywhere. You drive from habit, not looking at anything in particular before realizing you are back in Toronto, that your driving always takes you to the same place, that everything is familiar here, that it’s impossible to leave. Behind the wheel you are like King Midas, everything you touch turns into Toronto.”

To entitle his next work, Steve turned to his own name (and the name of his father), translating it into the language of the new world. “Sanguedolce” in English means “sweet blood.” This resodding of the old world marks the passage from father to son in a diary film of immigrants. Driven by a montage of fragmented voice-overs that draft an elegiac weave of recountings, Sweetblood‘s pictures are drawn from a family’s history of self-representation. These pictures have been mounted on a series of six foam coam boards, then photographed in single frame abandon, Sanguedolce presents a synoptic personal history begun with family weddings, and proceeding through grade school class photos, high school hipsters, a hockey montage, booze and drugs, a near fatal car accident, travels abroad, lovers and friends, the beginnings of his filmmaking career, and finally, a last, difficult attempt to reconcile himself with his family. Superimposed over his photographic frenzy are texts presented one line at a time. Culled from the maker’s dream diaries, they serve as reminders that family history is strained through language.

Away (60 minutes 1996) turns again to the subject of the Sanguedolce family, this time in the guise of fiction. Asked to crew on the set of Apocalypse Now by fellow paisan Francis Ford Coppola, Steve uses the interminable shooting breaks to search for his twin brother Sam. A carefully crafted mosaic of dramatic interludes, home movies, philosophic asides, and Apocalypse Now excerpts, Away turns around its absent centre with a desperate ferocity, seeking familial communion. Funny, beautiful and simply strange, Away is a hybrid work, part documentary, part fiction, looking to restore its broken blood compact with the balm of pictures.

After the successes of direct cinema moviemakers like Leacock and Pennebaker, it was hoped the widescale dissemination of home media equipment, specifically the introduction of super-8, would establish a grass roots imaging network that would loosen Hollywood’s fatal grip. The advent of cheap, portable home video recording will draft the next chapter in the ongoing struggle between private and public spheres. Sanguedolce’s work stands as an intermediary in this effort to broadcast the intimate and unforeseen, the unheralded shape of the everyday.

Original version published in The Millennium Film Journal No. 23/24 (Winter 1990-91)