Su Friedrich intro

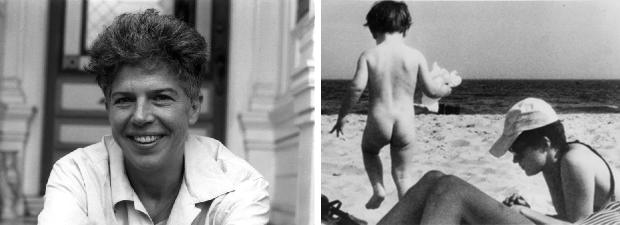

The year is 1988. The place is Toronto, in a small east end theatre called the Funnel, devoted to the exhibition of exotic movies. The night’s program is from New York, and it’s important to remember that eighties screenings had this weird, apocalyptic vibe to them. The end of the world, or at least, the end of this small world of small movies, was never far, so each screening would go on and on and on, because there may never be another one. All the work that night was very short and the program was very long, and in the midst of it there was one movie that felt like someone had swallowed a trade wind from the Gulf of Mexico and just blew it through the room. This sweet, aromatic breeze carried with it the promise of adventure, the adventure of a new voice and a new life in art, and a kind of magical genie that would convert even things you’d seen a thousand times before into something strange and terrifying and wonderful. The film was Gently Down the Stream, a flickering black and white monodrama based on a series of dreams which were scratched into emulsion. “I make a second vagina beside the first. I look in surprise. Which is the original?”

This was The Vagina Monologues before Broadway, a new way to say I, rooted in the body but not a prisoner of it, political without the program. The work is hand-made, it looks like it’s come from someone, like you could take a personality and work it up into emulsion and light. It’s not pre-swallowed or sweetened for TV, and after it’s over, and the lights go up and all the monosyllabic misfits, all of us social awkwards, we all sort of steal a glance at each other knowing that we’d taken the same ride out on some weird Tri-X light that made us feel different, look differently at our own bodies.

Two years later she was back in person with an hour long tough about her mother who had grown up in Nazi Germany, and Su had gone back there, walked in the ghost shoes following the voice she’d heard all her life. Maybe she’s afraid of what she’ll find there but she can’t help it, she’s committed to the dig. Finds the iron cross you wore if you had more than three kids, the place the school used to be, finds the bombing routes and goes back over dad’s divorce. If there’s stories here it’s because they have to be told, and Su’s right in there asking the hard questions like “Didn’t you know about it?” and “Couldn’t you do something to stop all that shit?” So you know this isn’t the History Channel, this is the little picture and the big picture all at once. It’s something that starts in the body and ends with something that even multi-national capital hasn’t figured a way to turn into sneaker adverts or come-ons for cars because it’s too close and too far away all at the same time.

So she’s on a roll now, she’s cooking, she’s figuring maybe she can do anything and then she does, she comes back in 1987 with a girl-girl drama she names Damned if You Don’t that begins with Black Narcissus and ends in the confessional because it’s about nuns, and what happens when you see more than you can look at, and pleasure did I mention that already? Pleasure is important here. It’s not like the pleasure in other fringe movies where they make you stare at a wall socket for thirty minutes before delivering, because pleasure belongs here, in this work, and there’s lots to go round so you don’t have to hang onto every morsel. There’s plenty more where that came from.

Later she jacks up the pop tunes and a sideways look at marriage in First Comes Love, shoots every brown-panelled station wagon in New York state for her structuralist break-up movie Rules of the Road, teams up with Janet Baus to make the activist doc The Lesbian Avengers Eat Fire Too, and then scorches us again with the hour long Hide and Seek in 1996. It’s a queer teen multiverse in sixties style, all done up with Rick Prelinger’s science shorts and up-to-the-minute, all grown ups saying what it is, what it was, and what it will be. Laying it all down like a road.

Today she’s going to show my favorite Su Friedrich number. It narrates the semiotics of subjectivity but it also makes you cry. Please join me in welcoming Su Friedrich.

Hide and Seek

Lesbian avenger Su Friedrich returns with Hide and Seek (63 minutes 1996), a coming out confessional about girls who love girls. Years earlier, her grainy, underlit Bolex musings had swept across the avant frontier, dishing a dream journal scratched into emulsion, and a pair of high caliber home movies (one for mom, another for dad) whose conceptual rigour and deeply lived politics signaled the coming of age of a new generation of film artists. But it’s hard to stay up on the wire long, especially making movies, where softness in any one of a thousand areas can sink an entire project. And while America has big government cash to prop up car makers and big banks and mercenaries, there’s nothing for artists, which is bad for poets and painters, and a catastrophe for film artists. So Friedrich’s come back with a shorter stick, and a producer and a camera person and a public spirited project designed to get the message out.

Her interview subjects are winningly personal, their sometimes painful recollections woven together with brief, dramatic vignettes of school girl affections and found footage exuberances. The endlessly inventive use of films within the film provides a heady stream of underwater swimmers, faux childhood marriage, monkey experiments, slow motion gymnasts, African hunters and family simulations. These beauty spot accompaniments wind around an almost-plot line following a tom boy named Lou (“Don’t call me Lucille!”) who undergoes the indignity of adolescence in the company of a best friend who may or may not be a crush. Lesbian telltales seem to follow her around, from word that the fave teacher is a homo, to glimpses of a sleeping girl having her arms idly stroked by classmates at the endless assembly, to science movies assuring her that any amorous interest in girls is only temporary. And definitely out of bounds.

Airless gender roles and repressive family structures are driven here by a normative science. But slowly these alibis of identity are worn away by the steady drip of personal experience. Who are we when we are unmoored from our descriptions? The commandments of gender roles are issued and policed from cop shops and classrooms and newspapers until “women” and “men” know how to behave. What if we could step outside all that fear masquerading as common sense? Or if there is no escape from the force fields of the picture world, perhaps at least the pictures themselves could change. Su Friedrich says we can and we must.